Abstract

Young people are frequently exposed to bullying events in the offline and online domain. Witnesses to these incidents act as bystanders and play a pivotal role in reducing or encouraging bullying behaviour. The present study examined 868 (47.2% female) 11–13-year-old early adolescent pupils’ bystander responses across a series of hypothetical vignettes based on traditional and cyberbullying events. The vignettes experimentally controlled for severity across mild, moderate and severe scenarios. The findings showed positive bystander responses (PBRs) were higher in cyberbullying than traditional bullying incidents. Bullying severity impacted on PBRs, in that PBRs increased across mild, moderate and severe incidents, consistent across traditional and cyberbullying. Females exhibited more PBRs across both types of bullying. Findings are discussed in relation to practical applications within the school. Strategies to encourage PBRs to all forms of bullying should be at the forefront of bullying intervention methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bullying is a sub-set of aggressive behaviour that involves repeated and intentional attempts to damage/distress a weaker victim by a more powerful perpetrator (Olweus 1978, 1993). It can manifest in many different ways and a key distinction is drawn between ‘traditional’ and ‘cyber’ forms. The former take place in real-world contexts, often face-to-face, whereas the latter are delivered via electronic communication media (Bauman and Bellmore 2015). The two forms of bullying are recognised as major public health concerns (Allison and Bussey 2016), which are associated with psychological distress (Hawker and Boulton 2000; Brewer and Kerslake 2015), depressive symptoms (Tynes et al. 2010), and in worst cases, suicide (Hinduja and Patchin 2010). While bullying often appears in early childhood, adolescence is a time when both traditional and cyber forms become especially prominent as the peer group grows in importance (Brown et al. 1994) and teenagers become frequent users of electronic communication devices (i.e. mobile phones, laptops) (Pew Research Centre 2013).

Relative to traditional bullying, cyberbullying is characterised by anonymity and an almost unlimited capacity to reach victims (Slonje and Smith 2008; Slonje et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2008). Such differences have led scholars to recommend investigations that directly compare the two forms within the same sample (Boulton et al. 2014; Machackova and Pfetsch 2016; Sticca and Perren 2013). While bullying is often regarded as a dyadic process, more attention is being placed on those that are present and witness a bullying incident, but do not actively participate, also known as bystanders. Specifically, it is how bystanders respond to both forms of bullying that may act to precipitate versus attenuate bullying and/or its negative effects. Such responses can take a positive or negative form depending on how the bystander chooses to react. For example, positive responses can foster help-seeking and emotional support for victims (DeSmet et al. 2014; Erreygers et al. 2016; Pöyhönen et al. 2012), whereas negative responses encourage the perpetrator or at least fail to challenge the bullying act and provide tacit support for it (Holfeld 2014; Jones et al. 2015; Tsang et al. 2011). Clearly, understanding what precipitates prosocial bystander responses can help inform anti-bullying interventions.

Extant research is inconsistent with regard to whether bystanders would be more likely to intervene in traditional versus cyberbullying. On the one hand, adolescents report increased positive bystander behaviour for traditional than for cyberbullying incidents (Patterson et al. 2016). This was attributed to the physical presence and authority figures in the offline environment. The online environment lacks clearly defined rules and presence of authority figures, making it easier for bystanders online to ignore the incident (Patterson et al. 2016). On the other hand, the online environment provides increased anonymity and autonomy to young people (Wong-Lo and Bullock 2014). It is these characteristics that allow young people to choose how to respond and control their self-presentation online (Madell and Muncer 2007; Valkenburg and Peter 2011). This perceived control online allows bystanders to positively intervene through communication technology in a private manner (Bastiaensens et al. 2015; Wong-Lo and Bullock 2014).

Moreover, Latane and Darley’s well-known social psychological research on diffusion of responsibility (DOR) for intervening to help someone in distress also leads to conflicting expectations about relative bystander support for victims of traditional versus cyberbullying (Latane and Darley 1976; see Hogg and Vaughn 2011). They found that the presence of other ‘onlookers’ tends to reduce a person’s willingness to intervene in a positive way via DOR (e.g. ‘there is no need for me to help since someone else will’). This could imply that the physical presence of co-onlookers of traditional bullying would lead to less positive bystander behaviour relative to cyberbullying. On the other hand, the likely greater number of virtual co-onlookers of cyberbullying might lead to less-positive behaviour than for traditional bullying incidents for the same reason.

Researchers have also considered moderator variables that could influence bystander responses to traditional versus cyberbullying and severity of the bullying incident and gender have been implicated. Young people are known to make evaluations about the likely impact of different types of bullying on victims (Chen et al. 2015; Williams and Guerra 2007) and so severity is thought to influence the bystander responses they make. However, again, there is inconsistency in extant research and theory. On the one hand, an onlooker of more severe acts of bullying may experience greater shame for not intervening in a positive manner (Bandura 1986; Cappadocia et al. 2012). Consistent with this line of thinking, some studies report that young people tend to offer help for more as opposed to less severe cyberbullying (Bastiaensens et al. 2014, 2015; Obermaier et al. 2016) and traditional bullying (Cappadocia et al. 2012; Forsberg et al. 2018). On the other hand, research has shown that many young people are aware that siding with victims runs the risk of becoming targeted by the bullies (Boulton 2013). It would be conceivable that adolescents may be less inclined to offer help as bystanders of more as opposed to less severe episodes of bullying because of the greater risk. But even that intuitively appealing notion is challenged because while some studies have found that adolescents regard cyberbullying as more serious than traditional bullying (Sobba et al. 2017; Sticca and Perren 2013), others have found that they are more inclined to intervene positively in the former (Bastiaensens et al. 2015; Madell and Muncer 2007; Wong-Lo and Bullock 2014). So, while the ‘helping victims is risky’ hypothesis may be applicable for traditional bullying, perhaps because positive bystander responses are potentially highly visible, the anonymous nature of online activity may provide opportunities to safely intervene on behalf of victims in severe acts of cyberbullying (Madell and Muncer 2007; Obermaier et al. 2016). Despite these inconsistencies in the body of research on bystander responses to bullying, findings do seem to be consistent with theory and evidence to suggest that the behaviour of young people around bullying is the product of them weighing up the risks and the benefits of different course of action (Boulton et al. 2017; Newman 2008). Thus, while the severity of a bullying incident is highly likely to moderate bystander responses, more research is needed to elucidate the details. In particular, does the influence of severity act in a similar or dissimilar way for traditional versus cyberbullying?

Considering the influence of gender on bystander behaviour, females tend to have more positive attitudes to providing peer support in general compared to males (Boulton 2005; Cowie 2000). This has also been found in relation to both traditional and cyberbullying (Bastiaensens et al. 2014; Cao and Lin 2015; Gini et al. 2008). This body of evidence suggests that the moderating role of gender is such that females will be more likely than males to exhibit positive bystander responses (PBRs) to bullying. However, the extent to which this holds true for cyber versus traditional bullying warrants further study.

Turning to the current study, the extant literature provides a clear rationale for further examination of young people’s PBRs in a way that allows direct comparisons of traditional and cyberbullying, females versus males and less versus more severe incidents. These three factors were examined as main effects with the following associated hypotheses/research questions:

-

1.

PBRs will be higher in cyberbullying than traditional bullying (Bastiaensens et al. 2015; Madell and Muncer 2007; Wong-Lo and Bullock 2014).

-

2.

Females will exhibit more PBRs than males (Bastiaensens et al. 2014; Cao and Lin 2015; Gini et al. 2008).

-

3.

Due to inconsistencies in extant findings, it was tested if PBRs would vary as a function of severity. As severity increases, the ‘helping victims is risky’ hypothesis (Boulton 2013) predicts less PBRs, whereas the hypothesis that there would be greater shame associated with not helping (Bandura 1986; Cappadocia et al. 2012) predicts more PBRs.

In addition, interaction effects were tested in order to examine:

-

4.

If the influence of severity acts in a similar or dissimilar way on PBRs to traditional versus cyberbullying, i.e. would there be an interaction between type of bullying and severity?

-

5.

Whether gender acts as a moderator of participants’ tendencies to intervene positively in traditional versus cyberbullying, i.e. would there be an interaction between type of bullying and gender?

-

6.

Whether gender acts as a moderator of participants’ tendencies to intervene positively as a function of severity, i.e. would there be an interaction between severity and gender?

Method

Participants

The local Ethics Committee approved this study. Data were collected from 868 early adolescents aged 11–13 years (47.2% female) drawn from two secondary schools in the UK, across school years 7 and 8. The sample recruited in the current study reflects that of those in middle school in the USA, between the 6th and 7th grades. The sample were recruited from urban schools based in the UK, Midlands, in the city and districts of Birmingham. Ethnicity data were not solicited at the request of the schools, but they are typical state-funded schools with around 1000 students from a range of ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds. Consent from participants and parents/guardians/head teachers was obtained.

Measures

As in previous studies (Bastiaensens et al. 2014; Patterson et al. 2017; Price et al. 2014), bystander responses were assessed in relation to six hypothetical vignettes. The three scenarios for traditional (verbal) bullying, and the three scenarios for cyberbullying, each contained a mild, moderate and severe incident. The level of bullying severity for both traditional and cyberbullying vignettes was differentiated by the intensity of the mean/aggressive comment, the repetitive nature of the incident and the extent to which the victim was upset. Such factors in the literature are known to impact perceived severity and increase negative feelings for the victim (Gini and Espelage 2014; Palladino et al. 2017; Wright et al. 2017), and as such, formed the rationale for the development of the severity categories for the vignettes. After each scenario had been read out by the researcher (to overcome any literacy/comprehension issues), participants were asked “What would you do in this situation? List as many things as you can think of”. Participants were encouraged to carefully think how they would respond and to write down their individual ideas as they came to them. Participants had about 15–20 min to consider these key questions, far more than is usually afforded to open questions incorporated into self-report questionnaires. Prior studies have shown that adolescents typically provide rich data when this method is adopted (Boulton et al. 2017).

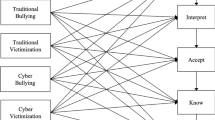

A coding frame was developed to allow quantitative analysis of participants’ responses. To develop this coding frame, prior research on bystander responses was consulted and reviewed (DeSmet et al. 2014; Erreygers et al. 2016; Patterson et al. 2016; Pöyhönen et al. 2012), which identified four specific common categories of positive response, shown in Table 1 with their operational definitions and exemplars of vignettes. The coding frame was reviewed by members of the school staff responsible for e-safety at the participating schools for additional views on the identified codes. Coding was conducted by two independent researchers. Inter-coder reliability across 120 responses from males and females to scenarios of different levels of severity yielded a Cohen’s Kappa of .623, regarded as ‘substantial’ (Peat et al. 2002; Viera and Garrett 2005). Examples of responses are, ‘Go and find a teacher straight away to tell them what happened’ and ‘Go to the person who has been bullied and make sure they are okay’, which were coded, respectively, as ‘Seek help from a trusted adult and/or teacher’ and ‘Provide emotional support and comfort the victim’. Additional examples can be seen in Table 1. To operationalise participants’ PBRs for each vignette, the number of responses from each of the four codes was tallied, giving each vignette a possible range of 0 to 4.

Procedure

Data were collected on a whole-class basis. Teachers were present but took no active part in proceedings. Participants received a questionnaire and were seated to ensure privacy. Their right to not take part or withdraw at any time was explained. They were informed that there were no right or wrong answers and encouraged to offer their own personal views. So that students and researchers had a shared understanding of key constructs, and to provide a context for the questions, the researcher discussed and defined ‘bystander’, ‘traditional bullying’, and ‘cyberbullying’.

Statistical Analysis

To address the hypotheses/research questions, a 2 × 3 × 2 (type of bullying [traditional, cyber] × severity [mild, moderate severe] × gender [male, female]) mixed ANOVA was performed along with follow-up tests. Type of bullying and severity were repeated measures and PBRs the dependent variable. Partial eta squared (η2) to determine effect size followed Cohen’s (1988) small (η2 = 0.01), medium (η2 = 0.06) and large (η2 = 0.14) effect level recommendations. The main effects are presented before describing if and how these were qualified by interaction effects.

Results

Confirming hypothesis 1, PBRs were significantly higher in cyberbullying (M = 3.86, SD = 1.79) than traditional bullying (M = 3.27, SD = 2.19), Wilk’s Lambda = 0.97, F(1,866) = 23.64, p < .001, partial η2 = .03.

Confirming hypothesis 2, females (M = 8.66, SD = 3.31) exhibited significantly more PBRs than males (M = 6.32, SD = 3.43), F(1,866) = 104.33, p < .001, partial η2 = .11.

For research question 3, PBRs did vary significantly as a function of severity, Wilk’s Lambda = 0.73, F(2,865) = 160.55, p < .001, partial η2 = .27. Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated PBRs for severe (M = 2.85, SD = 1.44) > than for moderate (M = 2.51, SD = 1.35) > than for mild (M = 2.07, SD = 1.36) bullying, all p < .001.

For research question 4, there was a significant interaction between type of bullying and severity, Wilk’s Lambda = 0.92, F(2,865) = 36.39, p < .001, partial η2 = .08. The nature of this interaction was probed with pairwise comparisons between traditional and cyberbullying at each of the three levels of severity; whereas there was no difference at mild (traditional: M = 1.01, SD = .90; cyber: M = 1.06, SD = .75) and severe (traditional: M = 1.45, SD = .95; cyber: M = 1.40, SD = .77) levels, at moderate levels PBRs were significantly higher for cyber (M = 1.40, SD = .77) than for traditional bullying (M = 1.11, SD = .85). In traditional bullying, there was a significant difference between each pair of severity level, all p < .001. Whereas in cyberbullying, each pair of severity level was significant, all p < .001, with the exception of moderate and severe, not significant. Figure 1 shows the interaction between type of bullying and severity on participants’ PBRs.

For research question 5, there was no evidence for an interaction between gender and type of bullying, Wilk’s Lambda = 1.00, F(1,866) = .16, p > .05.

For research question 6, there was a significant interaction between gender and severity, Wilk’s Lambda = .98, F(2,865) = 7.04, p < .001, partial η2 = .02. The nature of this interaction was probed with pairwise comparisons between females and males at each of the three levels of severity; for severe levels, PBRs were significantly higher among females (M = 3.34, SD = 1.36) compared to males (M = 2.41, SD = 1.36), t(866) = − 10.10, p < .001. At moderate severity, females (M = 2.93, SD = 1.27) had significantly higher levels of PBRs than males (M = 2.13, SD = 1.30), t(866) = − 9.16, p < .001. The mean difference at mild bullying severity indicated females (M = 2.38, SD = 1.30) compared to males (M = 1.78, SD = 1.36), t(866) = − 6.67, p < .001 were significantly more likely to exhibit PBRs. The nature of this interaction illustrates that females offer increasingly more PBRs than males as bullying severity increases. Figure 2 shows the interaction between gender and severity on participants’ PBRs.

Discussion

This study set out to examine the influence of severity and gender on early adolescents’ reported willingness to support victims of bullying and to directly compare traditional versus cyberbullying. In line with previous studies, our main effects analysis showed that the participants reported a greater willingness to intervene positively in cyber than traditional bullying (Bastiaensens et al. 2015; Madell and Muncer 2007; Wong-Lo and Bullock 2014), and females did so more than males (Bastiaensens et al. 2014; Cao and Lin 2015; Gini et al. 2008). A linear main effect of severity was obtained, with PBRs declining significantly from severe through moderate to mild cases. This is an important finding because it provides a direct test between two competing predictions derived from theory. It runs counter to the ‘helping victims is risky’ hypothesis (Boulton 2013) but is consistent with the view that onlooker of more severe acts of bullying may experience greater shame for not intervening in a positive manner (Bandura 1986; Cappadocia et al. 2012).

The finding that the effect of severity was qualified by type of bullying is a further contribution of the research. The main difference was that at moderate levels, PBRs were significantly higher for cyber than for traditional bullying, but that PBRs did not differ at mild and severe levels. Put another way, the threshold for relatively high amounts of PBRs ‘kicked in’ at moderate levels of severity for cyberbullying but at severe levels of severity for traditional bullying. These results have important practical implications. They suggest that with relatively little prompting on the part of adults (parents and teachers in particular), early adolescents could be persuaded to act on their apparent tendencies to support victims of cyberbullying but that efforts to encourage more widespread PBRs to traditional bullying may need to be substantial. Verbal bullying was chosen as an exemplar of traditional bullying and prior research has shown that many young people and adults fail to see this as ‘serious’, at least relative to physical traditional bullying (Boulton et al. 2014; Jacobsen and Bauman 2007; Maunder et al. 2010).

Research has identified that cyberbullying is often regarded as more serious than its traditional counterpart (Sobba et al. 2017; Sticca and Perren 2013) and in line with the current study, early adolescents feel more inclined to offer PBRs in the former. The finding that females were more likely than males to offer PBRs in both forms of bullying and at all levels of severity could be explained by their more proactive attitudes to provide peer support (Boulton 2005; Cowie 2000) and their stronger belief that bullying is serious (Molluzzo and Lawler 2012). Based on this, we suggest that efforts to communicate/reinforce the notion that all forms of bullying are serious may support the belief among young people that, correspondingly, all forms of bullying merit PBRs, especially among males. However, future research should explore whether these attitudes translate into their actual behaviour when acting as a positive bystander for both forms of bullying. A previous study showed that such beliefs may be engendered effectively by allowing older students to teach their younger peers about such matters (Boulton et al. 2016). This, in turn, may promote and encourage future PBRs across all pupils.

While the findings suggest the frequency of PBRs are similar across both forms of bullying, in particular, across levels of bullying severity, early adolescents were more likely to exhibit these behaviours in the online domain. It could be that early adolescents perceive cyberbullying incidents to be more public, a recognised feature attributed to the wider audience online (Slonje and Smith 2008; Slonje et al. 2013), and as such, offer more PBRs due to the increased perceived impact on the victim (Chen and Cheng 2017; Sticca and Perren 2013). In addition, the ability to conceal one’s identity in the online domain could influence bystander intentions. On the one hand, the anonymity online could hinder PBRs (Barlińska et al. 2013), while on the other hand, the feature could create a platform for bystanders to positively intervene in a safe and responsible manner (Dredge et al. 2014; Madell and Muncer 2007). Due to different reporting systems in the online and offline domain, adults can provide examples to young people on how to safely record and report witnessed incidents.

As noted in the Introduction, extant theory (Latane and Darley 1976; see Hogg and Vaughn 2011) suggests bystanders evaluate the incident severity and make decisions about (non)-intervention at least partly on the basis of DOR. In the original research, DOR was regarded as being a simple linear function of the sheer number of co-onlookers. When it comes to bullying, this simple approach needs to be refined because, as the current study noted, DOR may also be influenced by perceived severity and in the cyber domain, co-onlookers are not actually physically present. The findings showed that early adolescents exhibited more PBRs in cyber compared to traditional bullying, even though the former tend to be associated with a wider audience and hence a greater number of cyber bystanders The online domain creates challenges for bystanders, especially when evaluating the severity of the incident, as bystanders could misinterpret the severity of the event. However, consistent across both forms of bullying, PBRs increased with severity, attributed due to the greater shame experienced by bystanders by not intervening for more as opposed to less severe incidents (Bandura 1986). Research has shown how reduced self-efficacy can impact on bystander intentions (Thornberg and Jungert 2013), highlighting the role of social-cognitive theories/principles to encourage PBRs. Practical applications of this suggest schools should implement intervention strategies to encourage active reflection and discussion on appropriate bystander responses through role play and activities. This can enable early adolescents to practice and gain the skills necessary to be a positive bystander in both online and offline domains.

Some limitations of the current study need to be noted. Responses to vignettes are only proxies for social behaviour (Bellmore et al. 2012). Despite this, young people have shown consistency in their stated intentions (Turiel 2008) and so vignette methodology has some merits. In addition, while the vignettes provide a good measure of attitudes and what early adolescents think they would do when faced with particular situations, it is also possible these may not reflect their actual attitudes and behaviours. However, prior research on the relationship between what we say we do and what we actually do outlines the need to provide contextualised information to increase participants’ accuracy between their real and hypothetical choices (FeldmanHall et al. 2012). As outlined in the ‘Method’ section, key constructs were discussed to enhance understanding and provide context for the vignettes. Such procedures demonstrate the steps that were taken to increase the accuracy of the participants’ responses.

In addition, self-report data could reflect social desirable responses, with early adolescents overestimating their PBRs. However, steps were taken to minimise this possibility. While only verbal bullying was used to depict traditional bullying vignettes, this form of bullying has been recognised as the most prevalent of the traditional methods, and identified to most overlap with cyberbullying (Vandebosch and Van Cleemput 2009; Waasdorp and Bradshaw 2015). However, future research should compare bystander responses between different subsets of traditional and cyber forms of bullying. This would illustrate any discrepancy on PBRs across physical, verbal, relational and cyber forms of bullying. In particular, how PBRs vary according to the online platform and/or digital device used would aid future anti-cyberbullying initiates when developing new social networks or devices.

In summary, this study offers a unique comparison of PBRs between cyber and traditional bullying by considering the influence of bullying severity and gender. The findings contribute to research on bystanders by showing that early adolescents’ report increased PBRs in cyber than traditional bullying, with more PBRs as bullying severity increases across both types of bullying, particularly among females. This suggests the severity of bullying is an important predictor on subsequent bystander intentions, and so merits further investigation. They add to the growing body of knowledge that can be used to encourage more PBR among young people as an important way to combat bullying and its negative effects.

References

Allison, K. R., & Bussey, K. (2016). Cyber-bystanding in context: a review of the literature on witnesses’ responses to cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 183–194.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2013). Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: role of the communication medium, form of violence, and empathy. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(1), 37–51.

Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., Desmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Cyberbullying on social network sites. An experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 259–271.

Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2015). ‘Can I afford to help?’ How affordances of communication modalities guide bystanders' helping intentions towards harassment on social network sites. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(4), 425–435.

Bauman, S., & Bellmore, A. (2015). New directions in cyberbullying research. Journal of School Violence, 14(1), 1–10.

Bellmore, A., Ma, T. L., You, J. I., & Hughes, M. (2012). A two-method investigation of early adolescents’ responses upon witnessing peer victimization in school. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1265–1276.

Boulton, M. J. (2005). School peer counselling for bullying services as a source of social support: a study with secondary school pupils. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 33(4), 485–494.

Boulton, M. J. (2013). The effects of victim of bullying reputation on adolescents’ choice of friends: mediation by fear of becoming a victim of bullying, moderation by victim status, and implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114(1), 146–160.

Boulton, M. J., Boulton, L., Camerone, E., Down, J., Hughes, J., Kirkbride, C., & Sanders, J. (2016). Enhancing primary school children’s knowledge of online safety and risks with the CATZ cooperative cross-age teaching intervention: results from a pilot study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(10), 609–614.

Boulton, M. J., Boulton, L., Down, J., Sanders, J., & Craddock, H. (2017). Perceived barriers that prevent high school students seeking help from teachers for bullying and their effects on disclosure intentions. Journal of adolescence, 56, 40–51.

Boulton, M. J., Hardcastle, K., Down, J., Fowles, J., & Simmonds, J. A. (2014). A comparison of preservice teachers’ responses to cyber versus traditional bullying scenarios: Similarities and differences and implications for practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(2), 145–155.

Brewer, G., & Kerslake, J. (2015). Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 255–260.

Brown, B. B., Mory, M. S., & Kinney, D. (1994). Casting adolescent crowd in a relational perspective: caricature, channel, and context. In R. Montemayor, G. R. Adams, & T. P. Gullota (Eds.), Advances in adolescent development: Vol. 5. Personal relationships during adolescence (pp. 123–167). Newbury Park: Sage.

Cao, B., & Lin, W. Y. (2015). How do victims react to cyberbullying on social networking sites? The influence of previous cyberbullying victimization experiences. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 458–465.

Cappadocia, M. C., Pepler, D., Cummings, J. G., & Craig, W. (2012). Individual motivations and characteristics associated with bystander intervention during bullying episodes among children and youth. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 27(3), 201–216.

Chen, L. M., & Cheng, Y. Y. (2017). Perceived severity of cyberbullying behaviour: differences between genders, grades and participant roles. Educational Psychology, 37(5), 599–610.

Chen, L. M., Cheng, W., & Ho, H. C. (2015). Perceived severity of school bullying in elementary schools based on participants’ roles. Educational Psychology, 35(4), 484–496.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge Academic

Cowie, H. (2000). Bystanding or standing by: gender issues in coping with bullying in English schools. Aggressive Behavior, 26(1), 85–97.

Desmet, A., Veldeman, C., Poels, K., Bastiaensens, S., Van Cleemput, K., Vandebosch, H., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Determinants of self-reported bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents amongst adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(4), 207–215.

Dredge, R., Gleeson, J., & De La Piedad Garcia, X. (2014). Risk factors associated with impact severity of cyberbullying victimization: a qualitative study of adolescent online social networking. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(5), 287–291.

Erreygers, S., Pabian, S., Vandebosch, H., & Baillien, E. (2016). Helping behavior among adolescent bystanders of cyberbullying: the role of impulsivity. Learning and Individual Differences, 48, 61–67.

FeldmanHall, O., Mobbs, D., Evans, D., Hiscox, L., Navrady, L., & Dalgleish, T. (2012). What we say and what we do: the relationship between real and hypothetical moral choices. Cognition, 123(3), 434–441.

Forsberg, C., Wood, L., Smith, J., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Jungert, T., & Thornberg, R. (2018). Students’ views of factors affecting their bystander behaviors in response to school bullying: a cross-collaborative conceptual qualitative analysis. Research Papers in Education, 1–16.

Gini, G., & Espelage, D. L. (2014). Peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide risk in children and adolescents. Jama, 312(5), 545–546.

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., Borghi, F., & Franzoni, L. (2008). The role of bystanders in students’ perception of bullying and sense of safety. Journal of School Psychology, 46(6), 617–638.

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(4), 441–455.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2010). Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(3), 206–221.

Hogg, M. A., & Vaughn, G. M. (2011). Social psychology. Harlow: Pearson.

Holfeld, B. (2014). Perceptions and attributions of bystanders to cyber bullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 1–7.

Jacobsen, K., & Bauman, S. (2007). Bullying in schools: school counselors’ responses to three types of bullying incidents. Professional School Counseling, 11(1), 1–9.

Jones, L., Mitchell, M., & Turner, K. (2015). Victim reports of bystander reactions to in- person and online peer harassment: a national survey of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(12), 2308–2320.

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1976). Helping in a crisis: bystander response to an emergency. Morristown: General Learning Press.

Machackova, H., & Pfetsch, J. (2016). Bystanders’ responses to offline bullying and cyberbullying: the role of empathy and normative beliefs about aggression. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 169–176.

Madell, D., & Muncer, S. (2007). Control over social interactions: an important reason for young people’s use of the internet and mobile phones for communication? Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(1), 137–140.

Maunder, R. E., Harrop, A., & Tattersall, A. J. (2010). Pupil and staff perceptions of bullying in secondary schools: comparing behavioural definitions and their perceived seriousness. Educational Research, 52(3), 263–282.

Molluzzo, J. C., & Lawler, J. (2012). A study of the perceptions of college students on cyberbullying. Information Systems Education Journal, 10(4), 84.

Newman, R. S. (2008). Adaptive and nonadaptive help seeking with peer harassment: an integrative perspective of coping and self-regulation. Educational Psychologist, 43(1), 1–15.

Obermaier, M., Fawzi, N., & Koch, T. (2016). Bystanding or standing by? How the number of bystanders affects the intention to intervene in cyberbullying. New Media & Society, 18(8), 1491–1507.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: bullies and whipping boys. New York: Hemisphere Publishing.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Palladino, B. E., Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., Luik, P., Naruskov, K., Ucanok, Z., Dogan, A., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Hess, M., & Scheithauer, H. (2017). Perceived severity of cyberbullying: differences and similarities across four countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1524.

Patterson, L., Allan, A., & Cross, D. (2016). Adolescent bystanders’ perspectives of aggression in the online versus school environments. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 60–67.

Patterson, L. J., Allan, A., & Cross, D. (2017). Adolescent perceptions of bystanders’ responses to cyberbullying. New Media & Society.

Peat, J., Mellis, C., & Williams, K. (Eds.). (2002). Health science research: a handbook of quantitative methods. Sage.

Pew Research Centre (2013) Teens and technology 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2013/PIP_TeensandTechnology2013.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2016.

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2012). Standing up for the victim, siding with the bully or standing by? Bystander responses in bullying situations. Social Development, 21(4), 722–741.

Price, D., Green, D., Spears, B., Scrimgeour, M., Barnes, A., Geer, R., & Johnson, B. (2014). A qualitative exploration of cyber-bystanders and moral engagement. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 24(1), 1–17.

Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2008). Cyberbullying: another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00611.x.

Slonje, R., Smith, P. K., & Frisén, A. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.024.

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 49(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x.

Sobba, K. N., Paez, R. A., & ten Bensel, T. (2017). Perceptions of cyberbullying: an assessment of perceived severity among college students. TechTrends, 61(6), 570–579.

Sticca, F., & Perren, S. (2013). Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? Examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonymity for the perceived severity of bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9867-3.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483.

Tsang, S. K. M., Hui, E. K. P., & Law, B. C. M. (2011). Bystander position taking in school bullying: the role of positive identity, self-efficacy, and self-determination. TheScientificWorldJournal, 11, 2278–2286. https://doi.org/10.1100/2011/531474.

Turiel, E. (2008). Thought about actions in social domains: morality, social conventions, and social interactions. Cognitive Development, 23(1), 136–154.

Tynes, B. M., Rose, C. A., & Williams, D. R. (2010). The development and validation of the online victimization scale for adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(2).

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: an integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(2), 121–127.

Vandebosch, H., & Van Cleemput, K. (2009). Cyberbullying among youngsters: profiles of bullies and victims. New Media & Society, 11(8), 1349–1371.

Viera, A. J., & Garrett, J. M. (2005). Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Family Medicine, 37, 360–363.

Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), 483–488.

Williams, K., & Guerra, N. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), S14–S21.

Wong-Lo, M., & Bullock, L. M. (2014). Digital metamorphosis: examination of the bystander culture in cyberbullying. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(4), 418–422.

Wright, M. F., Yanagida, T., Aoyama, I., Ševčíková, A., Macháčková, H., Dědková, L., et al. (2017). Differences in severity and emotions for public and private face-to-face and cyber victimization across six countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(8), 1216–1229.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement

The research complies with ethical standards and ethical approval was granted for the research by the Department of Psychology, University of Chester.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Macaulay, P.J.R., Boulton, M.J. & Betts, L.R. Comparing Early Adolescents’ Positive Bystander Responses to Cyberbullying and Traditional Bullying: the Impact of Severity and Gender. J. technol. behav. sci. 4, 253–261 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-018-0082-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-018-0082-2