Abstract

Objectives

The techniques facilitation of activities, arrangement of task or situation, verbal and non-verbal communication, and counseling and empowerment of parents and caregivers are applied in different therapy approaches to improve motor function in children with neuromotor disorders. This review quantitatively examines the effectiveness of these four techniques allocated to pre-defined age groups and levels of disability.

Methods

We followed the systematic review methodology proposed by the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM). The search was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, PEDro, OT Seeker, ERIC, and CINAHL. The main outcomes of the included articles were allocated to the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (body functions, activities, and participation).

Results

The search yielded eleven studies for facilitation, 22 for arrangement of task or situation, three for verbal and non-verbal communication, and three studies for counseling and empowerment. The effect sizes indicated strong evidence for body function and activity outcomes for the use of facilitation in newborns until the age of 2 years and the arrangement of tasks in children between 2 and 5 years with cerebral palsy.

Conclusions

Thus, while some evidence exist for facilitation and arrangement of task or situation, further research is needed on the effectiveness of verbal and non-verbal communication and counseling and empowerment of parents and caregivers to improve motor function, activities, and participation.

Systematic review registration.

PROSPERO CRD42017048583.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Therapeutic professionals (e.g., physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists) apply treatment concepts and interventions within the rehabilitation of children with neuromotor disorders. A treatment concept usually consists of several techniques that compose the actual content of the therapy. A technique can be included in different treatment concepts or interventions and applied by professionals with diverse therapeutic backgrounds (Mayston, 2012). While various systematic reviews identified the effectiveness of different treatment concepts and interventions (Anttila et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2010; Novak et al., 2020), systematic reviews evaluating techniques are scarce. One review assessed the effectiveness of stretching, massage, strengthening, electrical stimulation, weight-bearing, balance, treadmill, and endurance training targeting lower limb function in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (Franki et al., 2012). While these techniques could positively influence various body functions (according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health – Children and Youth version (ICF-CY)), no change in the activity level was observed (Franki et al., 2012).

In line with this review, we aimed to determine the evidence concerning the effectiveness of four techniques applied within the management of children with neuromotor disorders to improve motor function, activities, or participation (Munsch et al., 2010). These techniques were chosen for the following reasons: facilitation as a process to enable the child to be active in an efficient way and to reach their own goals; the use of an arrangement of the task or situation that can be applied to facilitate and enable the child to be active and enhance self-regulation; the use of verbal and non-verbal communication to affect alertness, activity, and participation, counseling, and empowerment of parents and caregivers to set goals and enhance integration and quality of life (Munsch et al., 2010). In addition, for appropriate therapeutic management, it is essential to consider the child’s age and the severity of the disability. Therefore, it is relevant to look at and evaluate the evidence in different age groups and disability severity levels.

Facilitation is defined as guiding, accompanying, and reducing the manual sensory-motor input during a meaningful task chosen by the child (Capelovitch, 2017; Munsch et al., 2010). Furthermore, facilitation includes manual or bodily support of positioning in alignment to enable activity and participation, place and clarify the base of support, and provide a sensory input due to movement and activity (Capelovitch, 2017; Munsch et al., 2010). Arrangement of task or situation includes tasks with a specific level of action, difficulty, and motivation. In the current study, we allocated environmental and situational adaptations such as specifically adapted objects (e.g., toys), adaptation of the location or room, specific positioning of the child, therapist, caregiver, and objects (e.g., toys). Verbal and non-verbal communication includes gestures, facial expressions, body posture, and aid-supported communication; verbal communication includes melody, rhythm, timbre, volume, and focus of attention to enable the child’s activity. Finally, counseling and empowerment of parents, caregivers, and the child or adolescent with neuromotor disorder itself includes the dialogical process to enable these persons to understand and to act in a supporting way to enable the child or young person to gain more independence and quality of life.

We formulated the following research question: How effective are (a) facilitation of activities and movements, (b) arrangement of task or situation, (c) verbal and non-verbal communication, and (d) counseling and empowerment of parents and caregivers on improving outcomes classified on the levels body function, activities, or participation according to the ICF-CY in children and youths with neuromotor disorders? We consider this review of interest for a broad group of rehabilitation professionals as these techniques are applied within various disciplines. Furthermore, by summarizing the evidence, we hope to identify techniques that improve motor function and independence in children with neuromotor disorders.

Methods

Study Eligibility

This systematic review followed the methodological approach recommended by the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM) (Darrah et al., 2008). This is a step-by-step process to develop, conduct, and present a systematic review.

Studies were included if participants were diagnosed with neuromotor disorders such as CP, acquired brain injuries (ABI), and others (e.g., high risk for developmental disorders, myelomeningocele with hydrocephalus, syndromes with movement disorders); the participants’ age was between 0 and 20 years; the study was written in English or German; the level of evidence was I–IV (where I is the highest level; see Supplementary information S1) for the group and single-subject study designs; the effectiveness of one of the four techniques was investigated. In addition, peer-reviewed articles published between January 2000 and November 2020 were included, as with the introduction of the ICF in 2001, research became more focused on specific groups of children with CP. Furthermore, more attention was paid to using assessments with known psychometric properties (Damiano, 2014).

Exclusion criteria were defined for (1) facilitation: studies applying facilitation as “inhibitory technique,” or “in a passive way,” “to normalize movement,” “to manipulate” were excluded according to the definition of facilitation used in this study; (2) arrangement of task or situation: studies were excluded if they used solely virtually adapted environments or tasks; (3) non-verbal or verbal communication: studies with specific programs to enhance solely articulation were excluded, as this aspect was included in previous reviews (Morgan & Vogel, 2008; Pennington et al., 2016); (4) counseling and empowerment of caregivers and parents: studies which investigated solely the perception of the parents were excluded.

Literature Search

The literature search was conducted in the following electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, PEDro, OT Seeker, ERIC, and CINAHL (via EBSCOhost). The search was performed for each of the four techniques individually, according to the framework describing the techniques provided by Munsch et al. (2010) and in each database. Figure 1 shows the contents belonging to the four techniques (Munsch et al., 2010).

Search strategies were built with search terms according to the categories: (1) participants (e.g., cerebral palsy, neuromotor impairment, sensorimotor impairment), (2) techniques (e.g., facilitation, guiding movement, support position), and (3) professions (e.g., physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech, and language therapy). See Supplementary information S2 for the complete search strategies for the PubMed database. The original search was conducted in July 2018, and a follow-up search in all databases was performed in November 2020.

The first and second authors read the abstracts and independently decided whether an article was included by following the pre-defined inclusion/exclusion algorithm (Supplementary information S3). If there was no abstract available or if a decision could not be made based on reading the abstract only, the full text was screened. In case of disagreement, the authors discussed until consensus was met.

Search Results

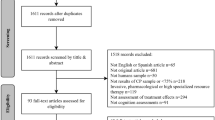

After excluding duplicates and including records from an additional search of the references, we found (a) 700 papers about facilitation, (b) 547 papers about arrangement of task or situation, (c) 2290 papers about the use of verbal and non-verbal communication, and (d) 72 articles about counseling and empowerment of parents and caregivers. Figure 2 displays the flowchart of the search, including reasons for exclusion. After screening the full texts, (a) eleven papers were included for facilitation, (b) 22 papers for the arrangement of task or situation, (c) three papers for the use of verbal and non-verbal communication, and (d) three for counseling and empowerment.

Data Extraction

The main outcomes were allocated to the ICF-CY framework. On the body function level, outcomes such as muscle strength, range of motion, or surface electromyography (sEMG), on the activity level, e.g., the gross motor function measure (GMFM), timed walking tests, or hand activity tests, and on the participation level, e.g., the pediatric evaluation of disability inventory (PEDI) or Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM). For the evidence synthesis, the studies including children with CP were allocated for the level of disability with the gross motor function classification system (GMFCS), and for four age groups: 0–2 years, 2–5 years, 5–12 years, and 12–20 years (Mayston, 2012).

Risk of Bias Assessments

Two raters independently rated the level of evidence and the quality of the studies with evidence level I, II, and III, using the AACPDM risk of bias assessment. Level IV studies will be described in Table 1 and not rated with the risk of bias assessments (Supplementary information S4).

Statistical Analysis

For the quantitative analysis, effect sizes (ES), including the 95% confidence intervals (CI), were calculated according to Hedges’ g, using the mean group differences (x1; x2) and the pooled standard deviation (SD) of the differences (Swithin) (Cooper et al., 2009). To calculate ES from ordinal data, the means and the SDs were calculated as follows: mean \({\varvec{x}}\sim \frac{{\varvec{q}}1+{\varvec{m}}+{\varvec{q}}3}{3}\), where q is the quartile (first or third) and m is the median, and SD \({\varvec{S}}\sim \frac{{\varvec{q}}3-{\varvec{q}}1}{{\varvec{\eta}}({\varvec{n}})}\), where η is a function of n, and n is the sample size (Wan et al., 2014). The ES should be interpreted in the context of similar research, i.e., the magnitude of effectiveness based on the context, and practical or clinical value of the research (Durlak, 2009). Therefore, the mean differences (pre–post measurements), also known as raw (unstandardized) mean differences, can be discussed in relation to the minimal detectable change (MDC) or the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), if available. To interpret the magnitude of the ES, we used the benchmark for ES suggested by Cohen: small ≤ 0.20; medium 0.21–0.79; large ≥ 0.80 (Cohen, 1988). The standard mean difference (SMD) of all baseline and intervention measurement time points (SMDall) was calculated for single-subject design studies (Olive & Smith, 2005).

With a random effect model, using the DerSimonian and Laird method, ES of comparable outcomes were calculated separately for (1) function and activities or (2) participation (Borenstein et al., 2011). Statistical calculations and forest plots were calculated with RStudio (250 Northern Ave, Boston, MA 02,210) using the “meta,” “metacont,” and “forest” packages.

Results

Study Characteristics: Interventions and Participants

Facilitation of Activities and Movements

Eleven studies of the category facilitation of activities and movements were included. Six of these studies were evidence levels I–III, and five studies evidence level IV. For the contents of the studies, see Table 1. The majority of the participants were diagnosed with CP (n = 695), and all GMFCS levels were represented. In two studies, children with a high risk to develop CP (born very preterm, with very low birth weight) were included (Cameron et al., 2005; Dirks et al., 2011). One study also included children with other neuromotor conditions in addition to children with CP (Evans-Rogers et al., 2015).

In two studies, the technique of facilitation was applied in the control group, while the COPing with and CAring for Infants with Special Needs (COPCA) approach was applied in the intervention group (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011; Hielkema et al., 2019). The authors named the approach for treating the control group traditional infant physiotherapy (TIP), which was based on neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT). These two studies were included in two categories of techniques, one facilitation (control group) and one caregiver counseling and empowerment (experimental group).

The quality rating of the studies evidence level I–III is presented in Supplementary information S4a. All rated studies were group design studies of weak-to-strong quality, including 10 to 487 children per study. The purposes of the studies were increasing motor strength, enhancing motor development and function, or improving gait.

Arrangement of Task or Situation

Twenty-two studies investigated the arrangement of task or situation. In Table 1, we present these studies separately for arrangement of task (n = nine studies) and arrangement of situation (n = 13 studies). The studies investigated the effectiveness of goal setting, task-oriented training, context-focused training (arrangement of task), and adaptation of positioning (arrangement of situation).

Three case–control level-IV studies evaluated the effectiveness of task-oriented training on the transfer of a reach-to-grasp task in daily life and the effectiveness of a functional goal approach (Knox & Evans, 2002; Robert et al., 2013; Schneiberg et al., 2010). Ten level IV studies investigated specific adaptations of seating equipment in wheelchairs, and one study evaluated the effectiveness of night-time positioning on sleep quality (Cimolin et al., 2009; Hill et al., 2009; Holmes et al., 2003; McDonald & Surtees, 2007; Rigby et al., 2001, 2009; Ryan et al., 2005, 2009; Sarmad et al., 2019; Vekerdy, 2007).

Seven of the nine studies targeting arrangement of task and two of the studies targeting arrangement of situation had evidence levels I–III. For the specific content of the studies, see Table 1. The majority of participants were diagnosed with CP (n = 523), and all GMFCS levels were represented. The quality synthesis was performed for nine evidence level I to III studies (n = seven studies arrangement of task; n = two studies arrangement of situation, one of them was a single-subject design study). The quality of these studies was weak to moderate (Supplementary information S4). A total of 267 children participated, the majority of them were diagnosed with CP (n = 233), and all GMFCS levels were represented.

Verbal and Non-verbal Communication

Three studies included communication as a specifically defined technique and were rated at evidence level IV. Two studies had a group design and one a single-subject design (Table 1). A total of 24 children were included, 21 with CP, two with undefined developmental delays, and one with Trisomy 21. The age ranged from 19 months to 10 years. One study investigated the effectiveness of training of parents and children to enhance the interaction between the children and their parents (Pennington & James, 2009). Another study, which lasted 2 years, compared a voice training that included a functional approach for postural control with the oral praxis approach (Puyuelo & Rondal, 2005). The third study investigated the use of an expression of the children and augmented communication on an individualized basis (Kent-Walsh et al., 2015). No study investigated the influence of verbal or non-verbal communication (such as feedback or interactive dialogue) on motor function, activities, or participation in children or youths with neuromotor disorders.

Counseling and Empowerment of Parents and Caregivers

Three studies applying counseling and empowerment of parents and caregivers were included; two level II studies of moderate quality and one level IV study. The level II studies evaluated the effectiveness of COPCA (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011; Hielkema et al., 2019). Both studies were already described in the paragraph about the facilitation technique since the control group received facilitation. In total, 144 children were included, of whom 77 were diagnosed with CP. The level IV study investigated the effectiveness of three different treatment approaches: Bobath concept, conductive education, and education of parents (Dalvand et al., 2009).

Study Outcomes, Measures, Results, and Effect Sizes

Table 2 presents the outcomes, measures, and results of the group design studies; Table 3 shows the ES. For one study, the ES could not be calculated as the results of the children with neuromotor disorders were not separately listed (Hielkema et al., 2019).

The evidence of the studies with evidence levels I–III is displayed in Fig. 3. We grouped the evidence for each of the four techniques, the defined age group, and the GMFCS level. In three studies, the GMFCS levels were not reported. Based on the descriptions, we classified the children as follows: (a) children with very low birth weight (12 developed moderate-to-severe CP and we classified them as GMFCS level III–V)(Cameron et al., 2005); (b) two of the four children were diagnosed with moderate bilateral CP, and we classified them as GMFCS level III (Washington et al., 2002); and (c) children with complex minor neurological dysfunctions (n = 15) and CP (n = 10) with GMFCS level I–IV (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011).

Evidence chart. Evidence of the four techniques (facilitation, arrangement of task or situation, counseling and empowerment of parents or caregivers, and communication) was obtained from the included studies with evidence levels I–III. The studies are grouped according to the GMFCS levels of the children (second inner ring), the age groups (third inner ring), and body function or activities level, or participation (outer ring). One study was not included in the evidence chart since the level of disability of the participants could not be estimated due to lack of a description (Vroland-Nordstrand et al., 2016)

Facilitation of Activities and Movements

Two studies investigated participation and applied the Alberta infant motor scale (AIMS) (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 2005). One study also applied the PEDI (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011). Two other studies investigated motor activities using the GMFM as an outcome measure (Kerem & Livanelioglu, 2002; Tsorlakis et al., 2004).

The study with the strongest level of evidence included 60 preterm babies with very low birth weight, of whom 12 developed CP (Cameron et al., 2005). In the group of children with CP, a non-significant improvement with a small ES of 0.15 (95% CI: − 1.05 to 1.35; Table 3) was found (Cameron et al., 2005). Blauw-Hospers et al. (2011) found minimal differences between COPCA and TIP. These changes did not influence the developmental outcome of the children at high risk for developmental disabilities. In one study with evidence level III (40), children with CP (n = 24) improved significantly in the GMFM-66 after intensive high-dose facilitation (NDT) during 16 weeks (ES = 0.78 (95% CI: 0.08 to 1.48). The mean pre–post difference (2.37 points) exceeded the MCID (1.58 points for GMFM-66) (42).

The pooled ES of the three studies investigating the effectiveness of facilitation on activity level, using the GMFM as an outcome, was large but not significant (ES = 3.78, 95% CI [− 6.73–14.28]), as shown in the forest plot, Fig. 4a (Kerem & Livanelioglu, 2002; Sah et al., 2019; Tsorlakis et al., 2004). The pooled ES of the studies reporting outcomes with the PEDI for participation (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 2005) was medium (ES = 0.26, 95% CI − 1.32 to 1.84; Fig. 4a).

Forest plots. Evidence of the four techniques (facilitation, arrangement of task or situation, counseling and empowerment of parents or caregivers, and communication) was obtained from the included studies with evidence levels I–III. The studies are grouped according to the GMFCS levels of the children (second inner ring), the age groups (third inner ring), and body function or activities level, or participation (outer ring). One study was not included in the evidence chart since the level of disability of the participants could not be estimated due to lack of a description (Vroland-Nordstrand et al., 2016)

Arrangement of Task or Situation

The study with the largest numbers of participants (n = 128) found improvements in the intervention (context-focused therapy approach) as well as in the control group (child-focused therapy approach) (Law et al., 2011). The PEDI, the GMFM-66, family empowerment scale (FES), and the assessment of preschool children’s participation were assessed. The raw ES (mean differences) of both groups exceeded the MCID of the GMFM-66. The control group showed greater improvement in the GMFM-66 and PEDI. The raw ES values obtained from the assessment of preschool children’s participation were small in both groups and did not exceed the MCID of 0.8 points (Table 3). For the FES, a large ES was found, favoring the context-focused therapy approach (Law et al., 2011).

A significant effect (medium ES) of task-oriented strength training of the lower limbs in five children aged 4 to 12 years was measured with the GMFM dimensions D and E and the timed up and go test (TUG) (Salem & Godwin, 2009). While five children with spastic bilateral CP attending a 6-week task-oriented intervention improved, five children receiving NDT improved as well, but improvements did not differ between the groups (Choi et al., 2011). Two of the five children of the NDT control group reached the maximum of the GMFM B (60 points) already before the intervention (Choi et al., 2011). Therefore, no improvement could be measured with this assessment due to the ceiling effect (Choi et al., 2011; Hahn et al., 2009; Ko et al., 2020; Law et al., 2011; Ogwumike et al., 2019; Salem & Godwin, 2009).

The pooled ES of the six studies reporting motor activity outcomes assessed with the GMFM was low (ES = 0.20, 95% CI − 0.20 to 0.71), i.e., similar outcomes in both the experimental and control intervention groups (Choi et al., 2011; Hahn et al., 2009; Ko et al., 2020; Law et al., 2011; Ogwumike et al., 2019; Salem & Godwin, 2009). The pooled ES of the studies reporting outcomes with the PEDI for participation were negative (ES = − 0.18, 95% CI − 0.59 to 0.23; Fig. 4b) (Hahn et al., 2009; Ko et al., 2020; Law et al., 2011; Vroland-Nordstrand et al., 2016). These results suggest that arrangement of the task resulted in comparable improvements to those of the control intervention.

Verbal and Non-verbal Communication

The body of evidence of the technique verbal and non-verbal communication improving motor function, activities, or participation is weak. The studies showed some effects. Children interacted more with other children and their parents after functional communication therapy (Pennington & James, 2009). Children with severe CP showed an increase in oral praxis after a functional approach with voice training (Puyuelo & Rondal, 2005). Three children with apraxia and developmental delays interacted better after receiving specific instructions for children using augmentative and alternative communication (Kent-Walsh et al., 2015).

Counseling and Empowerment of Parents and Caregivers

Only three studies assessed the effectiveness of counseling and empowerment of parents and caregivers on participation. The study by Blauw-Hospers et al. (2011) was already included in this review in the category of facilitation (control group). Despite some weaknesses described before, the study highlighted a positive effect of parental coaching when compared to passive handling of the children (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011). This effect was higher in children who had mothers with a low level of education compared to children whose mothers had a middle or high education level (Blauw-Hospers et al., 2011). The second study investigating COPCA found a similar neurodevelopmental outcome in infants at high risk of CP for both groups (COPCA and TIP) (Hielkema et al., 2019). However, because only the results of the total group of both of these studies (children with and without a neurological diagnosis) were presented, we could not calculate the ES of the group of children with CP.

The third study (evidence level IV) found a positive impact of parental education in activities of daily living, as well as positive aspects of conductive education and NDT Bobath (Dalvand et al., 2009). However, there was no significant difference between the three approaches (Dalvand et al., 2009).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize the evidence of the effectiveness of four techniques on motor function, activities, and participation applied in the treatment of children and youths with neuromotor disorders. Secondly, we wanted to allocate the evidence to different age groups and levels of disability.

The majority of the studies examined effects on the levels of body function or activities rather than participation, as shown in the evidence diagram in Fig. 3. Also striking is the lack of evidence for verbal and non-verbal communication and counseling and empowerment techniques to improve activities or participation. Although communication and counseling are usually techniques used in each therapeutic intervention, there is a lack of (particularly longitudinal) studies that examine their effect. While longitudinal randomized controlled trials would be difficult and costly to conduct, multiple n-of-1 single-subject studies could be a way to investigate these two important aspects of therapy.

Today, context-focused, goal-oriented therapies, as part of the arrangement of task or situation, count as evidence-based approaches (Law et al., 2011; Novak & Honan, 2019). However, evidence about the effectiveness of motor function, activities, and participation is missing, or, as it has been shown in this systematic review, ES is small. One reason could be the low contrast between the intervention and control treatment. While comparing an intervention group with a control group undergoing no therapy would increase the contrast, therapists are reluctant to withhold treatment. Another, more speculative, reason could be that children profited from the inclusion of different techniques in their therapy program. This assumption was verified by the results of Law et al. (2011), who investigated the effectiveness of context- and child-focused therapy and found a positive effect for both therapy approaches.

Evidence for the age group 12–20 years, and within this group, especially for the children with GMFCS levels IV and V, is lacking. As the GMFCS development curves show, children and adolescents with CP who belong to this age group often lose function (Hanna et al., 2009). In the sensitive phase of adolescence, body function greatly influences the development of independence in daily life and thus on integration into the community (Strauss et al., 2004). Therefore, research to evaluate the effect of therapy on the maintenance of function, well-being, and integration into the community should be promoted.

One major limitation of most studies included in this review is the poor description of the exact therapeutic content. While underlying principles, methods, and theories were explained in many studies, the description of the therapy sessions was such that treatments could not be replicated in clinical practice. Authors are advised to report their intervention and control protocols in line with the TIDieR guidelines (Hoffmann et al., 2014). Why not share a detailed program with the readers? This would help to transfer the valuable findings into clinical practice. Some studies gave broad conclusions without reporting the specific age groups or disability levels. Research reports should be specific, and these points should be taken into account. These are steps toward thorough knowledge translation from evidence to practice and vice versa.

Methodological limitations

Our approach was explicitly designed to search for studies using the four defined techniques rather than concepts or approaches, which are usually mentioned. As we searched with pre-defined terms, we could have missed studies that used certain techniques but did not include terms describing the techniques.

Only a few studies applied identical or comparable assessments, which allowed us to pool data and create forest plots. For example, the two studies on facilitation of activity both had positive significant ESs. However, since there was a large difference between their ESs, the pooled 95% CI crossed the zero line.

This study focused on studies investigating the effectiveness of four techniques, which are applied in the treatment of children with neuromotor disorders. Strong evidence was found for the use of facilitation in newborns until the age of 2 years and for the arrangement of tasks in children aged 2 to 5 years. No study with evidence level I–III reported the effectiveness of verbal or non-verbal communication techniques applied in therapy. To date, there is a lack of evidence (studies with an evidence level IV and V) for children aged 12 to 20 years with a more severe level of motor disability. Studies about the effectiveness of communication and counseling and the empowerment of parents and caregivers are scarce.

References

Anttila, H., Suoranta, J., Malmivaara, A., Mäkelä, M., & Autti-Rämö, I. (2008). Effectiveness of physiotherapy and conductive education interventions in children with cerebral palsy: A focused review. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(6), 478–501. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e318174ebed

Blauw-Hospers, C., Dirks, T., Hulhof, L., Bos, A., & Hadders-Algra, M. (2011). Pediatric physical therapy in infancy: From nightmare to dream? A Two-Arm Randomized Trial. Physical Therapy, 91(9), 1323–1338. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100205

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sohns.

Cameron, E. C., Maehle, V., & Reid, J. (2005). The effects of an early physical therapy intervention for very preterm, very low birth weight infants: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 17(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PEP.0000163073.50852.58

Capelovitch, S. (2017). The Bobath concept – Did globalization reduce it to a Chinese whisper? Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 59(5), 557. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13371

Choi, M., Lee, D., & Ro, H. (2011). Effect of task-oriented training and neurodevelopmental treatment on the sitting posture in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 23(2), 323–325. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.23.323

Cimolin, V., Piccinini, L., Avellis, M., Cazzaniga, A., Turconi, A. C., Crivellini, M., & Galli, M. (2009). 3D-Quantitative evaluation of a rigid seating system and dynamic seating system using 3D movement analysis in individuals with dystonic tetraparesis. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 4(6), 422–428. https://doi.org/10.3109/17483100903254553

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). LE Associates.

Cooper, H., Heges, L., & JC, V. . (2009). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed.). Russek Sage Foundation.

Dalvand, H., Dehghan, L., Feizy, A., Amirsalai, S., & Bagheri, H. (2009). Effect of the Bobath technique, conductive education and education to parents in activities of daily living in children with cerebral palsy in Iran. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-1861(09)70039-7

Damiano, D. L. (2014). Meaningfulness of mean group results for determining the optimal motor rehabilitation program for an individual child with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 56(12), 1141–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12505

Darrah, J., Hickman, R., O’Donnell, M., Vogtle, L., & Wiart, L. (2008). AACPDM Methodology to develop systematic reviews of treatment interventions. The American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM). https://www.aacpdm.org/UserFiles/file/systematic-review-methodology.pdf.

Dirks, T., Blauw-Hospers, C. H., Hulshof, L. J., & Hadders-Algra, M. (2011). Differences between the family-centered “COPCA” program and traditional infant physical therapy based on neurodevelopmental treatment principles. Physical Therapy, 91(9), 1303–1322. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100207

Durlak, J. A. (2009). How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(9), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004

Evans-Rogers, D. L., Sweeney, J. K., Holden-Huchton, P., Mullens, P., & a. . (2015). Short-term, intensive neurodevelopmental treatment program experiences of parents and their children with disabilities. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 27(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000110

Franki, I., Desloovere, K., De Cat, J., Feys, H., Molenaers, G., Calders, P., Vanderstraeten, G., Himpens, E., & Van Den Broeck, C. (2012). The evidence-base for basic physical therapy techniques targeting lower limb function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review using the international classification of functioning, disability and health as a conceptual framework. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 44(5), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0983

Hahn, M. E., Simkins, S. L., Gardner, J. K., & Kaushik, G. (2009). A dynamic seating system for children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Musculoskeletal Research, 12(01), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218957709002158

Hanna, S. E., Rosenbaum, P. L., Bartlett, D. J., Palisano, R. J., Avery, L., & Russel, D. J. (2009). Stability and decline in gross motor function among children and youth with cerebral palsy aged 2 to 21 years. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 51(1469–8749), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03196.x

Hielkema, T., Hamer, E. G., Boxum, A. G., La Bastide-Van Gemert, S., Dirks, T., Reinders-Messelink, H. A., Maathuis, C. G. B., Verheijden, J., Geertzen, H. B., & J., & Hadders-Algra, M. . (2019). LEARN2MOVE 0–2 years, a randomized early intervention trial for infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: Neuromotor, cognitive, and behavioral outcome. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(26), 3752–3761. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1610508

Hill, C. M., Parker, R. C., Allen, P., Paul, A., & Padoa, K. A. (2009). Sleep quality and respiratory function in children with severe cerebral palsy using night-time postural equipment: A pilot study. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics, 98(11), 1809–1814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01441.x

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Kadoorie, S. E. L., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Phelan, A. W. C., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ (online), 348(March), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

Holmes, K. J., Michael, S. M., Thorpe, S. L., & Solomonidis, S. E. (2003). Management of scoliosis with special seating for the non-ambulant spastic cerebral palsy population – A biomechanical study. Clinical Biomechanics, 18(6), 480–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(03)00075-5

Kent-Walsh, J., Binger, C., & Buchanan, C. (2015). Teaching children who use augmentative and alternative communication to ask inverted yes/no questions using aided modeling. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(2), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0066

Kerem, M., & Livanelioglu, A. (2002). Effects of neurodevelopmental therapy on motor development in children with cerebral palsy. Fizyoterapi Rehabilitasyon, 13(3), 117–123.

Knox, V., & Evans, A. L. (2002). Evaluation of the functional effects of a course of Bobath therapy in children with cerebral palsy: A preliminary study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 44(7), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2002.tb00306.x

Ko, E. J., Sung, I. Y., Moon, H. J., Yuk, J. S., Kim, H. S., & Lee, N. H. (2020). Effect of group-task-oriented training on gross and fine motor function, and activities of daily living in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 40(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2019.1642287

Law, M. C., Darrah, J., Pollock, N., Wilson, B., Russell, D. J., Walter, S. D., Rosenbaum, P., Galuppi, B., Russell, D. J., Walter, S. D., Petrenchik, T., Wilson, B., Wright, V., Russell, D. J., Walter, S. D., Rosenbaum, P., & Galuppi, B. (2011). Focus on function: A cluster, randomized controlled trial comparing child- versus context-focused intervention for young children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 53(7), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03962.x

Martin, L., Baker, R., & Harvey, A. (2010). A systematic review of common physiotherapy interventions in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 30(4), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2010.500581

Mayston, M. J. (2012). Therapists and therapies in cerebral palsy. In A. Halligan (Ed.), cerebral palsy (1st ed., pp. 124–148). Mac Keith Press.

McDonald, R., & Surtees, R. (2007). Changes in postural alignment when using kneeblocks for children with severe motor disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 2(5), 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483100701497057

Morgan, A. T., & Vogel, A. P. (2008). Intervention for dysarthria associated with acquired brain injury in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 3). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006279.pub2

Munsch, K., Imholze, A., Keller-Rudyk, B., Kirch-Erstling, S., Seidner-Boskamp, K., & Stamatopoulos, E. (2010). Therapieziele und ihre Realisierung in einer intensiven Therapiephase nach dem Bobath-Konzept. Physioscience, 6(01), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1245157

Novak, I., & Honan, I. (2019). Effectiveness of paediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(3), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12573

Novak, I., Morgan, C., Fahey, M., Finch-Edmondson, M., Galea, C., Hines, A., Langdon, K., Namara, M. M., Paton, M. C., Popat, H., Shore, B., Khamis, A., Stanton, E., Finemore, O. P., Tricks, A., te Velde, A., Dark, L., Morton, N., & Badawi, N. (2020). State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 20(2), 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-020-1022-z

Ogwumike, O. O., Badaru, U. M., & Adeniyi, A. F. (2019). Effect of task-oriented training on balance and motor function of ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Rehabilitacion, 53(4), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rh.2019.07.003

Olive, M. L., & Smith, B. W. (2005). Effect size calculations and single subject designs. Educational Psychology, 25(2–3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000301238

Pennington, L., & James, P. (2009). Effects of It Takes Two to Talk—The Hanen Program for Parents of Preschool Children With Cerebral Palsy: Findings from an exploratory study. Journal of Speech Language, and Hearing Research, 52(5), 1121–1138. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0187)

Pennington, L., Parker, N. K., Kelly, H., & Miller, N. (2016). Speech therapy for children with dysarthria acquired before three years of age. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Vol 2016, Issue 7). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006937.pub3

Puyuelo, M., & Rondal, J. A. (2005). Speech rehabilitation in 10 Spanish-speaking children with severe cerebral palsy: A 4-year longitudinal study. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 8(2), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13638490400025322

Rigby, P., Reid, D., Schoger, S., & Ryan, S. (2001). Effects of a wheelchair-mounted rigid pelvic stabilizer on caregiver assistance for children with cerebral palsy. Assistive Technology, 13(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2001.10132029

Rigby, P. J., Ryan, S. E., & Campbell, K. A. (2009). Effect of adaptive seating devices on the activity performance of children with cerebral palsy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(8), 1389–1395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.013

Robert, M. M. T., Guberek, R., Sveistrup, H., & Levin, M. M. F. (2013). Motor learning in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy and the role of sensation in short-term motor training of goal-directed reaching. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 55(12), 1121–1128. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12219

Ryan, S., Snider-Riczker, P., Rigby, P., Ryan, S., & Rigby, P. (2005). Community-based performance of a pelvic stabilization device for children with spasticity. Assistive Technology, 17(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2005.10132094

Ryan, S. E., Campbell, K. A., Rigby, P. J., Fishbein-Germon, B., Hubley, D., & Chan, B. (2009). The impact of adaptive seating devices on the lives of young children with cerebral palsy and their families. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.011

Sah, A., Balaji, G., & Agrahara, S. (2019). Effects of task-oriented activities based on neurodevelopmental therapy principles on trunk control, balance, and gross motor function in children with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy: A single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences, 14(3), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpn.JPN_35_19

Salem, Y., & Godwin, E. M. (2009). Effects of task-oriented training on mobility function in children with cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation, 24(4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2009-0483

Sarmad, S., Khan, I., Sadiq, S., & Noor, R. (2019). Effect of positioning on tonic labyrinthine reflex in cerebral palsy: A single-centre study from Lahore. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 69(4), 478–482.

Schneiberg, S., Mckinley, P. A., Sveistrup, H., Gisel, E., Mayo, N. E., & Levin, M. F. (2010). The effectiveness of task-oriented intervention and trunk restraint on upper limb movement quality in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 52(11), e245–e253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03768.x

Strauss, D., Ojdana, K., Shavelle, R., & Rosenbloom, L. (2004). Decline in function and life expectancy of older persons with cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation, 19(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.3233/nre-2004-19108

Tsorlakis, N., Evaggelinou, C., Grouios, G., & Tsorbatzoudis, C. (2004). Effect of intensive neurodevelopmental treatment in gross motor function of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 46(11), 740–745.

Vekerdy, Z. (2007). Management of seating posture of children with cerebral palsy by using thoracic-lumbar-sacral orthosis with non-rigid SIDO® frame. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(18), 1434–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280601055691

Vroland-Nordstrand, K., Eliasson, A. C., Jacobsson, H., Johansson, U., & Krumlinde-Sundholm, L. (2016). Can children identify and achieve goals for intervention? A randomized trial comparing two goal-setting approaches. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 58(6), 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12925

Wan, X., Wang, W., Liu, J., & Tong, T. (2014). Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14, 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Wang, H. Y., & Yang, Y. H. (2006). Evaluating the responsiveness of 2 versions of the Gross Motor Function Measure for children with cerebral palsy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.117

Washington, K., Deitz, J. C., White, O. R., & Schwartz, I. S. (2002). The effects of a contoured foam seat on postural alignment and upper-extremity function in infants with neuromotor impairments. Physical Therapy, 82(11), 1064–1076.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PM designed and executed the study and the data analyses and wrote the paper. JG collaborated with the design and writing of the study, the selection and rating of the studies. HvH supported the data analyses and collaborated with the design and writing of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. This work was supported by the Mäxi foundation, Switzerland.

Conflict of Interest

PM has, besides her work as a PhD student and physiotherapist at the Swiss Children’s Rehab of the University Children’s Hospital Zurich, the position as head of the Master of Advanced Studies (MAS) Entwicklungsneurologische Therapie (i.e., Neurodevelopmental Treatment) in Switzerland. She is a Bobath-trained pediatric physiotherapist. JVG is also a Bobath-trained pediatric physiotherapist. She currently works in research and in a clinical position. She is teaching motor learning and scientific writing at the DAS and the MAS Entwicklungsneurologische Therapie, respectively. HvH has no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marsico, P., Graser, J. & van Hedel, H. Effectiveness of Facilitation, Arrangement of Task and Situation, (Non-)verbal Communication, and Counseling of Caregivers in Children with Neuromotor Disorders: a Systematic Review. Adv Neurodev Disord 5, 360–380 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-021-00220-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-021-00220-y