Abstract

Environmental adaptation assessment on a trail is particularly critical in mountain regions, where factors such as poverty and the difficulty in earning an alternative livelihood, the lack of infrastructure, and a lack of policies and planning are magnified. Mountain trails represent unique paths into the wild. The need for a topographical approach to survey a mountain trail led us to use TruePulse 360B laser technology equipment and digital mapping in order to select and analyze a trail in a forested area based on environmental adaptation assessment. Since ancient times, mountain trails have been pathways to local prosperity because they were used for commercial trade. In the modern world, mountain trails are used for hiking, recreational walks in nature, as a method to bring the new generation close to wild forests by persons in wheelchairs or disabled people (those who are deaf or blind or have Down syndrome, etc.). The aim of this paper is not only to provide a digital map for various tourist teams, especially disabled ones, to use when visiting and exploring the natural beauty near the Wildlife Museum in order to manage the wild trails for the benefit and prosperity of the local community, but also to examine the environmental adaptation of this trail by taking into consideration the protection of nature. The constructing methods of a path, the materials that are used for the pavement and the optical adaptation with the nature are also a goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From ancient times, human needs have led people to follow pathways and move from one place to another to find food, clothing, water, etc., by using trails in nature. Today, hiking along mountain trails is an athletic activity or is a part of the touristic attraction in famous areas such as Mt. Olympus. Nature-based tourism and recreation activities (Thiene and Scarpa 2008) have led to a constant increase in the number of visitors to mountainous terrain (Ciesa et al. 2014; Arabatzis et al. 2010).

European Community institutions have encouraged multi-functionality, which enhances respect for the environment and the capacity to provide ecosystem resources, promote local people, and integrate the rural and urban worlds (Estrategia Territorial Europea 1999; Dwyer et al. 2003; Ploeg and Roep 2003; Stürck and Verburg 2017; Faludi 2013). Diversifying local economies helps reduce conflicts and optimizes benefits, increasing both space and time efficiency (Kato and Ahern 2009). From a developmental point of view, and due to their geomorphological characteristics and sensitive ecosystems, mountainous regions also present intrinsic disadvantages related to the modernization of their traditionally extensive economic production base or the creation of modern competitive production activities (Stergiadou et al. 2001; Soutsas et al. 2006).

A trail can be planned and managed to protect and enhance a natural area. A well-planned and correctly built pathway will be able to (a) keep trail users on a designated path, (b) introduce residents to natural areas, encouraging a sense of ownership and stewardship, (c) channel existing resources in natural areas where trails are being managed for invasive species removal, trail closures, restoration, and natural area expansion, (d) increase awareness of natural environment issues through personal experience and interpretive programming, and (e) provide more effective and efficient use of resources in the maintenance and management of infrastructure and natural resources while optimizing cost/benefits (City of Toronto 2013).

Etching mountain paths for the disabled is a big challenge, since the need for quality time in nature is getting higher and higher. So, being lovers of nature, we searched for hiking opportunities that would allow us to get to know Greek landscapes. But, despite the countless guides and websites dedicated to hiking, we could not find the information needed to determine whether or not a hike is suitable for disabled hikers. So, we researched Greek legislation in order to find instructions for planning a hiking trail for the disabled.

A big question that comes up in any conversation about disability and access to the outdoors is this: what are the barriers? Berman (2020) provides just a few actionable items that can be done: (a) drastically improve signage; (b) remove visual barriers at seat height; (c) widen trail entrances; and (d) include more seating that is marked on a map. In 2017, Antonneli et al. suggested that, for off-road mobility, some manual or power-assisted devices could be be self-driven by paraplegics, while non-power-assisted devices could be used by tetraplegics (Antonelli et al. 2019).

In the present research, using a topographical approach to survey environmental adaptation assessment of a mountain trail as a pathway to local prosperity, we tried to bridge the technical requirements of designing an interactive mountain trail adjacent to a Natural History Museum that accommodates the needs of disabled visitors.

Research area and methodology

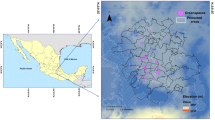

Taxiarchis Chalkidikis was chosen as the area for researching a planning strategy for forest paths and their impact on the opening of forest areas, recreation, and tourism, the importance of their technical specifications, and the legal framework that governs their construction and operation, as well as for highlighting the importance of forest paths for local communities, tourists, the disabled, and even nature itself. The Forest Museum, which has been operating since 2008 in University Forest of Aristotle’s University of Thessaloniki, displays both the flora and fauna of the area as well as its natural resources, and is the starting point and the end of the proposed path.

TruPulse 360B laser technology topographical equipment (Fig. 1) and the GGRS 87 (an application for coordinations which is based on earth satellites) were used in order to produce a topographical approach to surveying environmental adaptation assessment on a recommended mountain trail (Fig. 2).

TruPulse 360B and the measurement method. Source: https://arf.berkeley.edu/files/webfiles/all/arf/equipment/field/LaserRangeFinder/lti_trupulse_360_user_manual.pdf; Laser Technology, Inc. (2007)

The aim of this work was to create an easy path for hikers which will provide both recreation and education, as it will frame the University Facilities of the University Forest Taxiarchis—Vrastamon. This path can be a part of the visit to the University Forest Museum and the various other facilities that exist; at the same time, it will be connected to the already-existing trails of Cholomonta Mountain for environmental interest visits to the area. We relied on the Greek legislation regarding the definition of technical specifications for the design, marking, opening, and maintenance of mountaineering–hiking trails (ET. Β′ 206/30.01.2017 2017). Categories of mountaineering–hiking trails: A. Depending on the use of mountaineering—hiking trails, approach areas, length, degree of difficulty, and their type, they are divided into the following categories: (1) Long-distance trails, (2) Short-distance trails, B. Depending on their importance, mountaineering–hiking trails are divided into: (1) Primary mountaineering–hiking trails, which are of great importance that combine all the purposes of mountaineering trails. (2) Secondary mountaineering–hiking trails which are mainly branches of the primary mountaineering–hiking trails and have a shorter length. Types of mountaineering trails: 1. the mountaineering–hiking trails depending on the purpose they serve and the space they develop, are divided into different types: (a) Recreation—entertainment paths (R-E), (b) Educational–thematic (learning) paths (L), (c) Bicycle paths (B), (d) Trails accessible to the disabled (A), (e) living paths (domestic) (D) (Molokáč et al. 2022).

Planning design of the pathway

As path planners and foresters, we decided to design a pathway for disabled and for blind people who want to have experiences in nature (Fig. 3). Paths that are accessible to the disabled (AD) may be recreational paths (R-E), educational–thematic paths (L), or cycling paths (B), but they can also be special paths that were created to serve this special category of users or for therapeutic purposes (Berman 2020). The opportunity to visit places in nature is a right for all social groups, especially for people who cannot visit such places (which may bring them mental uplift and empowerment) unaccompanied.

Designing a new circular type of path for the disabled using a speedometer gave us a form of path with a low degree of difficulty and with a steep terrain part with a slope of up to 15%. The coordination is that GGRS 87 provide us our first planning design on field of a new circular trail for the disabled. We placed all the field measurements on an open data source Google map, and we provided 3D digital maps on the Google map using a satellite image (https://www.google.com/maps/@40.4317645,23.5047104,535m/data=!3m1!1e3). From Google Earth Pro, we obtained the elevation of the proposed path, the distance, the average inclination, and the geometric dimensioning (Figs. 4, 5).

Typically, the sections of a trail are classified based on the surface, width, and gradient of the trail. A multi-access trail is defined as class 1 throughout its length and has no obstacles such as steps, steep slope, and gates. That kind of path provides an accessible trail which complies with the requirements of “barrier-free access” for certain groups.

The geometric dimensioning of the pathway for the disabled was based on the universally proposed ones (United Nations 2003a): RAILINGS AND HANDRAILS: 1. Problem identification: (a) unsafe railings. (b) Hard to grip handrails. (c) No railings or handrails. 2. Planning Principle: To install adequate railing, wherever needed for the comfort and safety of all people, especially those with mobility problems. 3. Design considerations: General adaptations about Safety guards or railings should be installed around hazardous areas, stairs, ramps, accessible roofs, mezzanines, galleries, balconies and raised platforms more than 0.40 m high (Fig. 6).

Architectural design considerations (https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/designm/AD2-05.htm); United Nations (2003a)

In this part of the pathway, in order to have an environmental adaptation, we proposed to use (a) a wooden deck for the disabled, (b) yellow concrete tiles with special notches to guide blind visitors, and (c) an aluminum support bar for places where the slope of the path exceeds 5% ground slope (Fig. 7).

A trail can be planned by using environmental friendly materials and methods. Managed to help protect and enhance a natural area by using natural materials from the near quires. The environmental adaptation of the pathway is based on a government questionnaire. In that questionnaire, the planners are able to give their opinion about (a) the optical adaptation of the pathway pavement, (b) the materials that are used for the construction of the trail (whether they are ecofriendly or from natural resources), and(c) the possibility that the pathway could cause a landslide, flood, or any other hazard. The costless construction of the trail and the multiple uses of it make it more acceptable and adaptable to the local community.

Results

Proposed pathway for the disabled and blind as a prosperity plan

After the field measurements, the control of stability, and the possibility of accessibility to wheelchairs and the blind, the path was defined on an orthophoto map using the GIS program, and it can be used by disabled and the blind hikers (Fig. 8).

A walking path that follows the natural route of Forest Museum, as part of the visit to the University Forest, offers both a more meaningful type of tourism and an innovative approach to development (Fig. 9). An increasing trend in global tourism is for international adventure travelers to seek meaningful trips to places off the beaten track, where few have been before. They desire authentic and unique experiences that do not entail traditional luxury and comfort. These travelers also seek higher ethical and corporate social responsibility standards and see themselves not so much as package tourists but as contributors to new ideas, encounters, and ways of traveling. Exploring small villages such as Taxiarchis and places normally ignored by mainstream tourism is becoming part of that meaningful travel they seek.

Healers and people accompanying the disabled and the blind prefer places near nature. Support for experiential and nature tourism offerings such as the University Forest Museum trail is also an innovative way to create jobs in poor rural communities and to reach often-excluded groups such as the young people, families of disabled people, the blind, and other less fortunate groups of people, and in turn to reduce poverty and boost shared prosperity. Women are the key hosts of pathways in nature, managing and preparing lodgings and food while not necessarily having to leave their homes (which is important in traditional rural households). Local organizations can help boost the sale of local women’s handicrafts and traditional foods to walkers who pass through, or stay, in the village. The young acquire and hone foreign language skills with walkers and gain an early start to their careers while acting as guides to those passing through.

In addition to the economic gains generated from the path, communities benefit from increased social and natural capital—the respect, understanding, and knowledge gained as a result of welcoming outside visitors into their homes and communities. The longstanding Greek tradition of hospitality based on mutual trust and reciprocity is integral to the circular path which will frame the Forest Museum of Taxiarchis and connect local communities with foreign people from both close-by and distant areas. That kind of path for the disabled, the blind, and families connects hikers to the world and brings those new experiences and hope for meaningful living. The path helps shift outside perceptions and brings a renewed sense of local cultural identity.

Conclusions

Environmental adaptation assessment on a mountain trail is a planner’s job based on government legislation, and in our case the trail is perfectly adapted to the environment and to the purpose it was planned for. Planning a path in nature and near a Forest Museum using a topographical approach gives the opportunity to design a multi-use trail that can be constructed with local materials such as wood, stones, and cement, and gives new prospects for the visitors of the areas, especially kids, older people, the disabled, the blind, etc.

Based on the number of hikers and visitors to the Forest Museum (one-third of the cultural and social visitors), it was calculated that some of them could bring friends with small kids or disabled or blind people with them if they knew that there were recreational activities for these groups of people. The smells and the sounds of nature, the fresh air, and the hope that a disabled and/or blind visitor will experience will help their psychology and give them strength to go on with their life.

This educational trail as a path to local prosperity accomplishes the target of promoting local economic incomes, but there is always a way to plan more environmentally friendly pathways while also being generous to the local community. Furthermore, for the World Bank Group, non-traditional and experiential tourism such as paths for the disabled and the blind holds significant potential for generating income, jobs, and social capital not only across Chalkidiki but also in other rural, marginalized, and conflict areas. To meet the goals of reducing poverty and boosting shared prosperity, innovative approaches to tackling rural development, youth unemployment, and women’s empowerment in excluded communities are of vital importance.

With this paper we would like to encourage the Prefecture of Central Macedonia of Greece to plan and build paths for special groups of people such as the disabled and the blind, as this will reveal a more human profile of our culture as UN suggests for barrier-free accessibly groups.

References

Antonelli MG, Alleva S, Zobel PB, Durante F, Raparelli T (2019) Powered off-road wheelchair for the transportation of tetraplegics along mountain trails. Disabil Rehabil 14(2):172–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2017.1413431

Arabatzis G, Aggelopoulos S, Tsiantikoudis S (2010) Rural development and LEADER + in Greece: evaluation of local action groups. Int J Food Agric Environ 8(1):302–307

Berman A (2020) Hiking trails and maps often exclude people with disabilities. This group is changing that. Started by Syren Nagakyrie, Disabled Hikers aims to make the outdours more accessible for a diversity of people and marginalized communities. https://www.audubon.org/news/hiking-trails-and-maps-often-exclude-people-disabilities-group-changing. Accessed 19 Apr 2021

Ciesa M, Grigolato S, Cavalli R (2014) Analysis on vehicle and walking speeds of search and rescue ground crews in mountainous areas. J Outdoor Recreat Tourism 5–6:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2014.03.004

City of Toronto (2013) Natural environment trail strategy. https://www.cip-icu.ca/Files/Awards/Planning-Excellence/City-of-Toronto-Natural-Environment-Trail-Strategy.aspx

Dwyer J, Baldock D, Beaufoy G, Bennett H, Lowe P, Ward N (2003) Europe’s rural futures. The nature of rural development II: rural development in an enlarging European Union. WWF Europe/Institute for European Environmental Policy, Brussels/London

Estrategia Territorial Europea (1999) In Haciaun Desarrollo Equilibrado y Sostenible del Territorio de la U.E. [Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the EU]. EU Office of Publications, Luxemburg

Ministerial Decision (2017) Greek legislation regarding the definition of technical specifications for the design, marking, opening and maintenance of mountaineering–hiking trails. ET. Β’ 206/30.01.2017

Faludi A (2013) Territorial cohesión and subsidiarity under the European Union Treaties: a critique of the ‘territorialism’ underlying. Reg Stud 47:1594–1606

Handicap International (2016) General accessibility guidelines. https://sheltercluster.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/public/docs/iraq_general_accessibility_guidelines.pdf

Kato S, Ahern J (2009) Multifunctional landscapes as a basis for sustainable landscape development. J Jpn Inst Landsc Arch 72:799–804

Laser Technology, Inc. (2007) TruPulseTM 360/360B user’s manual. https://arf.berkeley.edu/files/webfiles/all/arf/equipment/field/LaserRangeFinder/lti_trupulse_360_user_manual.pdf

Molokáč M, Hlaváčová J, Tometzová D, Liptáková E (2022) The preference analysis for hikers’ choice of hiking trail. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/11/6795

Soutsas K, Tsantopoulos G, Arabatzis G, Christopoulou O (2006) Characteristics of tourism development in mountainous regions using categorical regression: the case of Metsovo (Greece). Int J Sustain Dev Plan 1(1):32–45

Stergiadou A (2001) Promotion; development; forest opening-up; mountain regions; technical works; environmental planning; geographical information systems (GIS); Grevena; Samarina; Kilkis; Krousia. PhD thesis. Aristotle’s University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, p 235

Stürck J, Verburg PH (2017) Multifunctionality at what scale? A landscape multifunctionality assessment for the European Union under conditions of land use change. Landscape Ecol 32:481–500

TheHouseShop (2015) Barrier-free homes in the UK. https://www.thehouseshop.com/property-blog/barrier-free-homes-in-the-uk/

Thiene M, Scarpa R (2008) Hiking in the Alps: exploring substitution patterns of hiking destinations. Tourism Econ 14(2):263–282. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000008784460445

United Nations (2003a) II. Architectural design considerations. 5. Railings and handrails. In: Accessibility: accessibility for the disabled—a design manual for a barrier free environment. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development, United Nations, New York. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/designm/AD2-05.htm

United Nations (2003b) I. Urban Design considerations. 4. Pathways. In: Accessibility: accessibility for the disabled—a design manual for a barrier free environment. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development, United Nations, New York. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/designm/AD1-04.htm

Van der Ploeg JD, Roep D (2003) Multifunctionality and rural development: the actual situation in Europe. Multifunct Agric New Paradig Eur Agric Rural Dev 3:37–54

Acknowledgements

This research was funded via a project: “Path network in the University Forest of Taxiarchi,” based on a contribution from the Fund for Administration and Management of University Forests of Aristotle’s University of Thessaloniki, Greece. It also forms part of the master’s thesis “Forest engineering and topography” of the Ph.D. candidate Mr. Moutsopoulos Dimitrios. Part of our research was funded by the Administration and Management Fund of University Forests (TDDPD) through the MODY—ELKE AUTH with a project code of 98707, a research object of “Path network in the University Forest Taxiarchi,” and a duration from 05/28/2019 until the end of 2021.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Antonis Zorpas.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moutsopoulos, D., Stergiadou, A. & Psilovikos, T. Environmental adaptation assessment on a mountain trail as a pathway to local prosperity based on a topographical approach. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 7, 545–552 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-022-00334-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-022-00334-2