Abstract

This study attempts to analyze the beneficiary selection and allowance utilization of social safety net (SSN) programmes in Bangladesh through using field level primary data. It finds that SSN transfers are not always distributed among the poor and vulnerable people who deserve to receive the allocation for fighting against poverty and vulnerability. We find that more than half of the selected beneficiaries under SSN programme do not comply with one or more priority criteria of the programme. Sometimes, the compulsory criteria are also overlooked while selecting beneficiaries. Such a scenario urges for revising and monitoring the beneficiary selection process. The study findings also indicate that about 60% of the received allowance money is spent for purchasing food, which signals that people still remain in vulnerable situation even after taking shelter under the umbrella of SSN. Therefore, an initiative to increase in allowance amount, change in beneficiary selection procedure and intensification of monitoring might contribute to promote human rights and social protection in Bangladesh through facilitating right peoples’ access to SSN programmes and boosting up SSN allowance amounts for fighting against poverty and vulnerability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bangladesh has experienced a remarkable progress in reducing poverty over the time period. The poverty rate has declined at a rate of roughly one percentage point per annum over several years (Ahmed 2007). The country has mostly fulfilled the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of halving the 1990 poverty rate by 2015 through macroeconomic and institutional policy reforms. The incidence of poverty has declined from 48.9% in 2000 to 40% in 2005, to 31.5% in 2010 and to 24.8% in 2015. Similarly, the percent of people below the lower poverty line has declined from 34.3 in 2000 to 17.6% in 2010 and to 12.9% in 2015 (Government of Bangledesh (GoB) 2015). However, the extent of poverty and vulnerability is still alarming in the country. The absolute number of poor and vulnerable people is still very high. Recognizing this reality, the government of Bangladesh has been emphasizing on social protection as a pillar of poverty reduction. A well-functioning safety net is an important element of social protection strategy to fight with poverty (World Bank 2006).

Social protection has recently gained predominance and political support almost without precedent in the context of the development and poverty reduction discourse (Sepúlveda and Nyst 2012). Social protection transfers help individuals to strengthen and accumulate productive assets and thus help them to enhance their future income earning capacity (Barrientos and Scott 2008; Alderman and Yemtsov 2012). Holmes et al. (2008) suggest that social protection reduces the constraints faced by extremely poor households to engage in productive activities. Evidences signal that social protection programmes can significantly contribute to reducing the prevalence and severity of poverty (Barrientos and Niño-Zarazua 2010). Sabates-Wheeler and Devereux (2008) suggest that social protection must address social vulnerabilities caused by structural inequalities and inadequate rights in addition to providing economic support.

The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) proclaims social protection as a basic human right. ILO (2011) suggests that social protection can contribute to women’s empowerment and social cohesion. UNICEF’s Social Protection Strategic Framework illustrates that social protection should directly support actions that tackle social exclusion in accessing services and achieving an adequate standard of living (UNICEF 2012). The constitution of Bangladesh guarantees social protection as a fundamental right. The ministry for social welfare in Bangladesh places special attention on socioeconomic development and improvement of life standard for the poor (Ahmed and Islam 2011). The government launches social safety net (SSN) programmes to reduce income uncertainty and variability, maintain a minimum standard of living, and redistribute income from the rich to the poor (Iqbal 2008) for promoting human rights and social protection in the country.

The SSN programmes in Bangladesh include cash and in-kind transfers, micro-credit schemes, and conditional cash transfers for widows, disabled, blind, orphans, aged, and such other disadvantaged groups. Each programme has its own objectives and procedures. The coverage of these programmes is very low and reaches to a very small part of the targeted population. On the other hand, despite the low coverage, multiple SSN programmes often serve the same beneficiary, and benefits often go to those who do not need assistance.

Fighting with poverty is the ultimate objective of the SSN programmes being undertaken by the government of Bangladesh since 1998. The local level government mainly implements the SSN programmes in the country. However, the inefficiency of local government failed to deliver the expected quality and quantity of social services in some cases. The limitations in beneficiary selection process, absence of proper follow up and monitoring system, and lack of poor people’s access to information regarding the social initiatives are constraining the efficiency of the SSN initiatives. In addition, lack of transparency, accountability, and responsiveness of local government denies poor peoples’ access to social initiatives and services.

Corruption and lack of accountability are common in SSN programmes of Bangladesh which has made the public sector SSN programmes somewhat dysfunctional. Some common types of irregularities related to SSN programmes are:

-

Some local government bodies (for example, union parishad) do not have the knowledge about SSN programme and its implementation process.

-

The union parishad does not follow participatory way in beneficiary selection process.

-

There is a prevalence of corruption and nepotism in beneficiary selection process resulting in providing benefits to people who do not meet the selection criteria.

-

The beneficiary selection committees are sometimes non-functional.

-

Updated beneficiary list resulting from death, exclusion or inclusion, and related other information of SSN programme are not easily available.

-

Sometimes, the mass people are in dark about the eligibility criteria of being a beneficiary.

-

The beneficiaries of SSN services sometimes do not receive information regarding the distribution date and time from respective implementing institutions timely which results late or abandoned payment.

-

The beneficiaries are sometimes harassed by the service providers or implementing agencies while distributing goods/services.

-

In some cases, beneficiaries do not receive full amount of allowance and often get poor quality of goods.

A well-functioning safety net is an important instrument of social protection. However, the limited coverage and inefficiencies within programmes hinder the stated programme objectives. A mixed result is evident in addressing the objectives of the SSN programmes in Bangladesh. While the programmes are valuable in smoothing consumption, the contribution of the programme is not remarkable for structural changes in poverty (World Bank 2006).

Materials and Methods

There are 30 specifically designed SSN programmes in Bangladesh (Morshed 2009) which are directly operated by the government covering 8 unconditional programmes, 10 conditional programmes, 5 credit schemes, 3 conditional subsidy programmes, and 4 funds. In addition, there are 15 funds to provide further assistance for improving the overall condition of the poor (Ahmed 2007). At least 14 ministries are engaged in planning and implementation of these programmes. In addition to these ministries, the Bangladesh Bank and Palli Karma Sahayak Foundation (PKSF) are also involved in operating SSN programmes. Involvement of multiple ministries and institutions causes considerable overlap in programmes and administration which stretch the administrative and resource capacity of the country (Ahmed 2005). The existing SSN programmes do not provide a sufficient basis to cope with the magnitude of extreme poverty. On average, 39% of eligible households are covered by different programmes. Therefore, more than 60% of eligible households are yet to get benefit from a suitable SSN programme.

The transfer mechanism in Bangladesh is generally homogeneous among the SSN programmes, where benefits are transferred to individual beneficiaries. A general guideline is usually prepared by the implementing agency of each programme. The guideline mentions certain targeting criteria according to the theme of the programme. These criteria usually include income level, asset and household structure, and demographic features. The local government body, such as union parishad, in consultation with other local agencies and community, identify the beneficiaries based on such criteria (Ahmed 2007).

Although the SSN programmes have gained momentum in the country, the beneficiary selection and allowance utilization are two vital issues to be evaluated to improve the state of SSN programmes. Accordingly, the objectives of this study are:

-

To analyze the beneficiary selection process for SSN programme

-

To assess the utilization of SSN allowance by the beneficiaries

The homogeneity feature of the transfer mechanism in Bangladesh allows us to frame the methodology of this study through selecting some of the ongoing SSN programmes instead of covering all to narrow down the study coverage. However, random sampling is applied in selecting the SSN programs for the sake of generalization of the study findings. Accordingly, this study randomly chooses (through following simple random sampling technique) two programmes from the ongoing 30 SSN programs to address the study objectives. These are ‘old age allowance’ and ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute.’ The ‘old age allowance’ programme served 2.475 million beneficiaries in 2012–2013 at the expenses of 8.91 billion Bangladesh Taka (GoB 2013). About 7.4% residents of the country are elderly people of age 60 and above (Barikdar et al. 2016). The coverage for ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute’ programme was 0.92 million beneficiaries with a budget of 3.31 billion Taka in 2012–2013 (GoB 2013). Widowed, divorced, and abandoned women constitute about 11.29% of total married women of Bangladesh. However, the available data on poverty, elderly, and widowed people are grossly inadequate to estimate incidences of poverty among the older and widowed people.

The ‘old age allowance’ and ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute’ programmes are in operation in almost every union of Bangladesh. However, due to time and other limitations, the Gongarampur union at Batiaghata upazilla under Khulna district of Bangladesh was purposively selected as study site for this study. The socioeconomic feature of the people living in the union mostly matched with the other areas of the country. The total area of the union was 9273 acres with 17,065 people in 3787 households (BBS 2001). Among nine wards of the union, this study randomly picked three: ward nos. 7, 8, and 9 for collecting primary data through following simple random sampling procedure. The study (through following simple random sampling technique) selected 188 respondents covering 122 ‘old age allowance’ and 66 ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute’ receivers and collected primary information through using an interview schedule. The interview schedule includes socioeconomic aspects such as income, expenditure, family size, age, land holding, marital status, and so on. It also includes the amount of received allowance and its usage. To address the first objective of the study, the matching between the collected data with the requirements of being the member of the SSN programmes was analyzed. Similarly, the disqualification criteria of the programmes were also considered for tracing out the discrepancies (if any) for meeting the first objective. The utilization of the received allowance money was also compiled through interview schedule to address the second objective of the study.

Result and Discussion

Beneficiary Selection for SSN Programme

‘Old Age Allowance’ Programme

This study considered one compulsory criterion and six priority criteria for assessing the beneficiary selection process under ‘old age allowance’ programme in the study area. The survey findings of 122 respondents from the 3 wards of the study area are summarized in Table 1. The compulsory criterion was met by all of the surveyed respondents. However, none of the recipients fulfilled all the priority criteria. Specifically, none of the beneficiaries fulfilled the income (criteria-1) or poor freedom fighter (criteria-3) related priority criteria. The coverage of disability (criteria-2) criterion was also insignificant. A good number of recipients fulfilled the land (criteria-4) and marital status (criteria-5) related criteria. About half of the respondents fulfilled the expenditure (criteria-6) related criterion. The scenario attracts attention for changing the selection criteria or intensifying monitoring process or both.

There were five disqualification criteria of the ‘old age allowance’ programme and more than one-third (46 out of 122) of the surveyed recipients fell within these disqualification criteria. Table 2 shows the distribution of recipients among five disqualification criteria. Receiving financial support from elsewhere was the leading disqualification criterion that was observed among the surveyed respondents.

‘Allowances for the ‘Widow, Deserted, and Destitute’ Programme

This study considered two compulsory criteria and four priority criteria for assessing the beneficiary selection process under ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute’ programme in the study area. The survey findings on 66 respondents from the three wards of the study union are summarized in Table 3 which clearly demonstrates that two recipients did not fulfill the first compulsory criteria, but they were getting allowance. All of the recipients fulfilled the second compulsory criterion of being a minimum of 18 years old.

None of the recipients fulfilled all the priority criteria. Specifically, none of the beneficiaries fulfilled the income (criteria-1) related priority criterion. The coverage of disability (criteria-2) criterion was negligible. Similarly, the number of recipients who fulfilled the land (criteria-3) or having children (criteria-4) related criteria were insignificant. This scenario also attracts attention for changing the selection criteria or intensifying monitoring process or both.

There were six disqualification criteria of the ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute’ programme and more than three-fourth (50 out of 66) of the surveyed recipients fell within these disqualification criteria. Table 4 lists the distribution of recipients among six disqualification criteria. Receiving financial support from elsewhere was the leading disqualification criterion followed by receiving allowance from other safety net programmes.

The survey findings indicate that priority criteria were often overlooked in selecting beneficiaries of SSN programmes. Even in some cases, the compulsory criteria were also not fulfilled by the recipients. It is clearly a misuse of government fund. Lack of proper selection procedure and monitoring are the reasons behind such discrepancies.

Utilization of SSN Allowance by the Beneficiaries

The second objective of the study was to assess the utilization of SSN programme allowance by the beneficiaries. It considered a total of 188 (=122 + 66) recipients under ‘old age allowance’ and ‘allowances for the widow, deserted, and destitute’ programme to address this objective. The utilization of the latest allowance received by the beneficiary was analyzed in this study (Table 5). A major share (60%) of the received allowance was spent for food followed by health care (19%). The share of other expenditure sources was insignificant covering less than 5% each (Table 5). Therefore, it may be said that, in the study area, a majority of the allowance receivers are vulnerable people of the society. That vulnerability binds them to spend the lion’s share of the received allowance for food purchase.

Consequence of not Getting Access to SSN Programme

The beneficiaries of SSN programs in Bangladesh are in general poor vulnerable people having limited access to basic human needs. Data suggest that a large proportion of poor and vulnerable households in Bangladesh do not have any access to the SSN programmes (GoB 2015). Consequently, they become economically more vulnerable. Hunger and aggravated poverty are the ultimate consequences in many cases for the elderly and widows who do not get access to the SSN benefits. Micro-level corruption is also observed in some cases as the indirect consequence of not getting access to SSN benefits, if not direct. Hence, non-inclusion in SSN programs ultimately exacerbates the social harmony and structure of the country. In contrast, as Bangladesh has ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, the country has some obligations in these areas. Therefore, it is very important to think about how to increase the number of beneficiaries under the SSN programmes in Bangladesh.

Conclusion

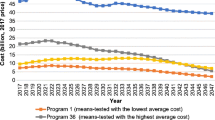

This study finds that the beneficiary selection process of SSN programme in Bangladesh is erroneous. We find that the selection of 96 (=46 + 50) out of 188 (=122 + 66) beneficiaries do not comply with the set beneficiary selection criteria. It means that 51% of the beneficiaries were wrongly selected through bypassing the selection criteria. Assuming that this scenario is true for the whole country and considering the country level macro data on budget and SSN allocation (Table 6), the rough calculation suggests that nearly US$ 2.86 billion were allocated for the wrongly selected beneficiaries during 2007–2008 to 2011–2012 time periods!

While searching the reasons behind the wrong selection of beneficiaries, this study finds that while there are rules and regulations for selecting right people for the programmes, most of the problems related to benficiary selection take place during the implementation phase. During the survey, we observed that the implementing authority was not well informed about beneficiary selection process in some cases. Moreover, corruption and nepotism invited beneficiary selection through non-participatory approach in some cases. The beneficiary selection committees were non-functional in some cases. Sometimes, an updated eligible candidate list was not available for selecting deserving beneficiaries. Information on eligibility criteria and deadlines were not disseminated properly in some other cases. The above listed issues are the main reasons for wrong beneficiary selection.

The findings of this study clearly demonstrate the importance of addressing the beneficiary selection process to promote human rights and social protection in Bangladesh. Proper monitoring will help to implement the existing rules and regulations in beneficiary selection process. Information dissemination, awareness development, and participatory approach will also work toward addressing the arisen inefficiencies. Strengthening the local government bodies that are the prime movers in selecting beneficiaries and implementing the programmes and making their activities transparent will also help to bring efficiency in the process. Such initiatives will contribute toward selecting the right people for the social protection transfers, which will ultimately help to address poverty, economic hardship, vulnerabilities, and human rights (Alderman and Yemtsov 2012; Barrientos and Niño-Zarazua 2010; Barrientos and Scott 2008; Holmes et al. 2008; ILO 2011; Sabates-Wheeler and Devereux 2008; Sepúlveda and Nyst 2012).

The literature states that social cash transfers often enable beneficiaries to make investment in productive activities and enhance their earning capacity (Devereux et al. 2005; Gertler et al. 2006; Alderman and Yemtsov 2012). Barrientos and Scott (2008) suggest that social transfers need to be regular and reliable and offer adequate level of support in order to facilitate household investment and graduation from poverty. However, it is evident from the study area that more than 60% of total allowances received by the beneficiaries are spent for food expenditure. It indicates that people are remaining under vulnerable situation even after taking shelter under the SSN programme. For the very reason, any type of sustained improvement may not be visualized in the socioeconomic condition of the beneficiaries. Therefore, it may be assumed that the current state of beneficiary selection, implementation, and monitoring may hinder in promoting human rights and social protection in Bangladesh, the ultimate objective of the safety net programme.

This study finds that none of the surveyed beneficiaries fulfilled all of the compulsory and priority criteria of selection. For some priority criteria, the number of selected beneficiary is nil. Therefore, this study recommends reviewing the beneficiary selection criteria of SSN programmes to promote human rights and social protection in Bangladesh. Moreover, as the major share of the received allowance is spent for food, this study recommends considering an increase in the allowance amount. Such an increase might help the recipients to channel some of the allowance money toward productive use which might help them graduating out of vulnerability and poverty over the time period, which is the prime mover for promoting human rights and social protection.

The main limitation of this study is considering a small sample size (N = 288) and focusing on only one selected location. Hence, covering a wider sample from diversified locations might help to validate and check robustness of the study findings.

References

Ahmed, R. U., & Islam, S. S. (2011). People's perception on safety net programmes: a qualitative analysis of social protection in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Development Consultant and Global Compliance Initiative (DCGCI) for Social Protection Group in Bangladesh.

Ahmed, S. S. (2005). Delivery Mechanism of Cash Transfer Programs to the Poor in Bangladesh. Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 0520, World Bank, Dhaka, 1–47.

Ahmed, S. S. (2007). Social Safety Nets in Bangladesh. World Bank Report, Dhaka, 1–21.

Alderman, H. and Yemtsov, R. (2012). Productive Role of Social Protection and Labor. Discussion Paper No. 1203, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Barikdar, A., Ahmed, T., & Lasker, S. P. (2016). The situation of the elderly in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics, 7(1), 27–36.

Barrientos, A., & Niño-Zarazua M. (2010). The effects of non-contributory social transfers in developing countries: a compendium. Geneva: International Labour Organization (ILO).

Barrientos, A. and Scott, J. (2008). Social Transfers and Growth: A Review. Working Paper No. 52. Brooks World Poverty Institute, Manchester.

BBS. (2001). Khulna District community series (pp. 1–64). Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Ministry of Planning, Govt. of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh.

Devereux, S., Marshall, J., MacAskill, J., & Pelham, L. (2005). Making cash count: lessons from cash transfer schemes in east and southern Africa for supporting the most vulnerable children and households. London: Save the Children UK, HelpAge International and IDS.

Gertler, P., Martinez, S. and Rubio-Codina, M. (2006). Investing Cash Transfers to Raise Long Term Living Standards. Policy Research Working Paper No. 3994, World Bank, Washington, D.C.

GoB. (2011). Budget speech of Bangladesh 2011–2012 (pp. 1–168). Dhaka: Ministry of Finance, Govt. of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh (GoB).

GoB. (2013). Budget speech of Bangladesh 2013–2014 (pp. 1–117). Dhaka: Ministry of Finance, Govt. of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh (GoB).

GoB. (2015). National social security strategy (NSSS) of Bangladesh (pp. 1–117). Dhaka: General Economics Division, Planning Commission, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (GoB).

Holmes, R., Farrington, J., Rahman, T. and Slater, R. (2008). Extreme Poverty in Bangladesh: Protecting and Promoting Rural Livelihoods. ODI Project Briefing 15, London.

ILO. (2011). Social protection floor for a fair and inclusive globalization. Geneva: International Labour Organization (ILO).

Iqbal, M. A. (2008). Macroeconomic implications of social safety nets in the context of Bangladesh (pp. 1–25). Dhaka: Center for Policy Dialouge (CPD).

Morshed, K. A. M. (2009). Social safety net programmes in Bangladesh (pp. 1–15). Dhaka: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Sabates-Wheeler, R., & Devereux, S. (2008). Transformative Social protection: the currency of social justice. In A. Barrientos, & D. Hulme (Eds.), Social protection for the poor and poorest: Concepts, policies and politics (pp. 64–84). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sepúlveda, M., & Nyst, C. (2012). The human rights approach to social protection. Finland: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

UNICEF. (2012). Integrated social protection systems: enhancing equity for children, UNICEF social protection strategic framework. New York: UNICEF.

World Bank. (2006). Social Safety Nets in Bangladesh: An Assessment. Bangladesh Development Series Paper No. 9, World Bank (WB), Dhaka, 1–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the survey respondents for providing valuable information. Acknowledgements are also due to Economics Discipline, Khulna University, Bangladesh for granting permission to conduct the study as a partial fulfillment of MDS degree. However, the views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the respondents or of the concerned organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haider, M.Z., Mahamud, A. Beneficiary Selection and Allowance Utilization of Social Safety Net Programme in Bangladesh. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2, 45–51 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-017-0028-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-017-0028-1