Abstract

Sleep disorder is very common during pregnancy. Non-pharmacological treatments are a priority to improve the sleep pattern. This study aimed to determine the effect of cognitive–behavioral counseling with or without Citrus aurantium essential oil on sleep quality (primary outcome) and anxiety and quality of life (secondary outcomes). This randomized controlled trial was performed on 75 pregnant women in Tabriz, Iran. Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups. The first intervention group received 8 sessions of cognitive–behavioral counseling and aromatherapy with Citrus aurantium essential oil 15–20 min before bedtime. The second intervention group received cognitive–behavioral counseling and aromatherapy with placebo and the control group received only routine prenatal care. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Pregnancy-Specific Quality of life Questionnaire, and Pregnancy-Specific Anxiety Scale were completed before and after intervention. After the intervention based on ANCOVA test and by adjusting the baseline score, the mean score of anxiety in the intervention group 1 (AMD: − 4.54; 95% CI − 6.79 to − 2.28) and intervention group 2 (AMD: − 3.30; 95% CI − 5.60 to − 0.97) was significantly lower than the control group. Also, the mean score of quality of life in intervention group 1 (AMD: 2.55; 95% CI 0.45–4.65) and intervention group 2 (AMD: 2.72; 95% CI 0.60–4.83) was significantly higher than the control group, but there was no statistically significant difference between the study groups in terms of sleep quality (P > 0.05). Also, there was no statistically significant difference between the two intervention groups after the intervention in terms of anxiety (P = 0.379) and quality of life (P = 0.996). Cognitive–behavioral counseling reduced anxiety and improved quality of life. However, further trials are required to reach a definitive conclusion. Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT): IRCT20120718010324N63. Date of registration: 4/10/2020. URL: https://en.irct.ir/user/trial/54986/view; Date of first registration: 18/10/2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sleep is a physiological state due to relative unconsciousness and inactivity of voluntary muscles [1]. Sleep in adults has two stages including Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) [2]. Sleep quality refers to the mental indicators of each person the way of experiencing sleep (for example, feeling rested when waking up, and sleeps satisfaction) [3].

Sleep disturbances are one of the most common problems during pregnancy [4]. Examination of sleep patterns during pregnancy indicates that 66–94% of pregnant women have changes in their sleep patterns [5]. The quality and the quantity of sleep vary in different periods of pregnancy. It is associated with negative maternal, fetal, and pregnancy outcomes [6]. The most common sleep disturbances during pregnancy are obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, and gastroesophageal reflux disorder. The etiology of these disorders is multifactorial; it might be associated with physical (hyperemesis, nocturia, heartburn, joint and back pain, nasal congestion, contractions, thermoregulatory issues, fetal movements, uncomfortable or unusual sleeping positions, dreams, and nightmares), and mental (primarily depression and anxiety) causes. Physiological, hormonal, and metabolic adaptations during pregnancy usually interrupt mother’s sleep–wake cycle [7].

Sleep disturbances may be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as anxiety, preeclampsia, miscarriage, preterm delivery, and longer first and second stage of labor [8]. Dritsa et al. reported that pregnant women with sleep disturbances have poor physical function [9] and social health, and physical pain and limitations of daily activity increase in these individuals [10].

Anxiety is a natural and adaptive reaction to the experience of unsafe or threatened feeling. It is common during pregnancy; the risk factors are a history of high anxiety or depression, perfectionism, history of miscarriage(s), high-risk pregnancy, and major life stressors [11]. Anxiety during pregnancy may adversely affect fetal development [12]. At current, a group of antidepressants and sedatives and antipsychotics is at the first line of pharmacological treatment of sleep disturbances during pregnancy, which is limited information on the safe use of these medications in pregnancy [13].

Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) is a combination of cognitive and behavioral approaches. CBT reduces cognitive, physical, and behavioral symptoms through the use of specific methods including relaxation, regular desensitization, cognitive reconstruction, response prevention, problem-solving, activity listing, and training of interpersonal skills [14]. The content of therapy includes identifying thoughts and beliefs, reviewing evidence, and examining cognitions and thoughts that are related to mood and behavior [15]. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is a structured program to identify and replace thoughts and behaviors that cause or worsen sleep disturbances with practices that promote proper sleep. The five main components of CBT-I are cognitive restructuring, sleep consolidation, stimulus control, sleep hygiene, and relaxation techniques [16].

Herbal medicines have been used widely since old days in ancient civilizations [17]. Aromatherapy is one of the treatments that have grown increasingly in recent years compared to complementary medicine treatments [18]. According to a recent systematic review, various essential oils, such as lavender, bergamot, and chamomile, have improved sleep quality and reduced stress, pain, anxiety, depression, and fatigue [19]. These oils help individuals to relax their bodies and minds, leading to better sleep quality. Also, some aromas may increase slow-wave sleep (SWS) and subjective sleep quality [20]. One of the essential oils used in aromatherapy is Citrus aurantium. This essential oil is an amber-colored liquid that turns red in the presence of light. Its smell is strong, very fragrant and its taste is bitter [21]. Citrus aurantium has central nervous system stimulating and mood-enhancing effects, as well as sedative, antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory, anti-flatulence, digestive, antihypertensive and diuretic effects [22]. Citrus aurantium essential oil contains 35% of various hydrocarbons, 42% of terpene alcohols, such as linalool, tripenel, geranium, nerol, flavonoids and their acetate, 6% of nerolidol and 0.7–1.1% of indole [23]. Based on the literature review, limited studies have been found about the effect of Citrus aurantium on sleep quality, anxiety, and quality of life of pregnant women. In a recent study, this essential oil was effective in reducing the anxiety of women at risk of preterm labor [24]; it was also effective in reducing anxiety during labor in another study [25]. No study has been conducted with the integration of CBT and aromatherapy.

Considering that poor sleep quality has detrimental effects on mood, psychological function and overall well-being [26] and given the various studies have reported the sedative and anxiolytic effects of Citrus aurantium [22], and also CBT helps the patient to recognize and change distorted thought patterns and dysfunctional behaviors [14]. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of cognitive–behavioral counseling with and without Citrus aurantium on sleep quality (primary outcome), anxiety and quality of life (secondary outcomes) in pregnant women.

Methods

Study design and participants

This randomized controlled trial was conducted on 75 pregnant women referring to health centers in Tabriz, Iran from July to February 2021.

The inclusion criteria included pregnant women with a gestational age of 20–24 weeks, women with poor sleep quality based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (score above 5), having a minimum degree of secondary school, living in Tabriz, having a medical record in the health center (integrated health system), lack of olfactory problems and allergy to herbal medicines by examination by the researcher, obtaining a depression score of 12 and lower according to the Edinburgh Pregnancy Depression Scale (EPDS). The exclusion criteria included pregnant women with mental illness and a history of hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital or the use of any psychiatric medication, addiction to drugs and smoking, high-risk pregnancies including diabetes, hypertension, chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular, lung, etc., obstetric problems including hemorrhage, history of preterm delivery, etc.

The sample size in this study was calculated using G-Power software. According to the results of the study conducted by Effati et al. [27] on the variable of sleep quality, considering M1 = 10.2 (mean score of sleep quality in the control group), M2 = 7.65 (assuming 25% reduction due to intervention), SD1 = SD2 = 2.8, one-sided α = 0.05, and Power = 90%, the sample size was calculated at 22 people in each group, considering the probability of 15% dropout in the samples, the final sample size was determined to be 25 people in each group.

Sampling

Sampling began after obtaining the code of ethics from the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TBZMED.RECD.1399.905) and its registration in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT20120718010324N63). Sampling was performed in 6 health centers of Tabriz, Iran. The researcher referred to health centers in Tabriz, and then briefly explained the goals and methods of the research to women with 20–24 gestational ages. If women were willing to participate in the study, they were examined in terms of inclusion and exclusion criteria and eligible individuals were selected. Then, the PSQI and the EPDS were completed through interview with participants by the researcher and participants who scored sleep quality score higher than 5 and a depression score 12 and less, and met other inclusion criteria were included in the study after obtaining informed written consent and then the socio-demographic characteristics questionnaire, Pregnancy-Specific Anxiety Scale (PSAS) and Pregnancy-Specific Quality of life Questionnaire (QOL-GRAV) were completed through interview with participants by the researcher.

Randomization

Participants were randomly allocated to three groups including the first intervention group (receiving cognitive–behavioral counseling with aromatherapy with Citrus aurantium essential oil), the second intervention group (receiving cognitive–behavioral counseling and placebo), and control group using the block randomization method with the block sizes of 6 and 9 and an allocation ratio of 1:1:1. The type of intervention was written on paper and placed in opaque and sealed envelopes that numbered sequentially to conceal the allocation sequence. The envelopes were opened in the order in which the participants entered the study and the type of group of individuals was determined. Envelopes were prepared by a person not involved in sampling, data collection and analysis. Similar glasses of Citrus aurantium essential oil or placebo were prepared and coded with letters of A and B. The Citrus aurantium essential oil and placebo had exactly the same appearance (smell, color, and shape). The intervention groups received a glass of drug or placebo in addition to counseling. The researcher and participants of intervention groups were blinded to the type of drug received.

Intervention

The first and second intervention groups received 8 sessions of cognitive–behavioral counseling held in the health center in groups of 5–7 people. The mean duration of counseling sessions was 60–90 min. Cognitive–behavioral counseling sessions were by the first author (Master of Counseling in Midwifery) under the supervision of the project clinical psychologist in health centers held as 2 sessions per week and lasted for 4 weeks.

The content of the counseling included explaining the goals of training and acquaintance with the members, conducting a pre-test, explaining the importance of treatment, assessing the insomnia, perception of sleep and insomnia, evaluating thoughts, training relaxation, sleep health and new sleep schedules, restriction of sleep, prevention of daily naps, problem-solving skills, summarizing thoughts, reality of sleep, introducing the cycle of thought and feeling and behavior, and training thought blocking. Due to COVID-19 disease, the last two sessions were held online in the Zoom program due to unwillingness of pregnant women to attend the health center. The content of the counseling sessions was as follows:

The first week

Session 1: Explaining the goals of training and acquaintance with members, conducting a pre-test, teaching how to monitor the baseline of sleep with a sleep report table, reminding the importance of treatment tasks, a complete assessment of the nature of insomnia.

Session 2: Presenting the principles and logic of treatment, teaching the mechanism of sleep and its stages, sleep–wake cycles and underlying factors, maintenance and continuation of insomnia, relaxation training.

The second week

Session 3: Reviewing the previous session of treatment, reviewing the findings of the sleep report form, sleep hygiene training, and review the relaxation and new sleep schedule.

Session 4: Restricting sleep, preventing daily naps, evaluating thoughts and teaching how to record thoughts related to insomnia and reviewing the assignments of previous sessions (sleep report form and homework schedule).

The third week

Session 5: Summarizing thoughts, problem-solving skills, reviewing the sleep report form and homework and troubleshooting.

Session 6: Introducing the cycle of thinking, feeling and behavior, reviewing relaxation and training not to try fall asleep and apply all the instructions of the previous sessions and reviewing the homework of the previous sessions (sleep report form and homework table).

The fourth week

Session 7: Training thought blocking, mental imaging, troubleshooting cognitive-behavioral therapy plan, reviewing patient homework.

Session 8: Reviewing and troubleshooting the cognitive–behavioral treatment plan, noting the progress of treatment according to the sleep calendar to the patients.

The participants in the first intervention group, in addition to cognitive–behavioral counseling sessions, received aromatherapy with Citrus aurantium essential oil, so that they placed 2 drops of Citrus aurantium aromatic distillate on a tissue and inhaled it through normal breathing for 15–20 min before bedtime. The Citrus aurantium essential oil required for the study was purchased from Bu Ali Sina Medical Company of Iran and after determining the concentration by gravimetric method was used by the Faculty of Pharmacy of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The safe dosage was 8 mg of Citrus aurantium essential oil in 100 ml of distilled water. Based on the evaluations made by the pharmacist, the minimum number of drops was considered for pregnant women. The second intervention group received a placebo with the same prescription. The content of the placebo were distilled water. A kind of aroma was used to make the placebo smell similar to Citrus aurantium essential oil when opening the lid of container; however, it didn't have the potential to stimulate the nervous system. The control group received only routine prenatal care.

The research tools

Data collection tools included the socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics questionnaire, PSAS, PSQI, and QOL-GRAV, which were completed before and after the intervention through interview with participants.

The PSQI is a self-report tool scored from 0 to 21 and developed by Buysse et al. [28]. This questionnaire has seven components that include subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, and sleep disturbances, the use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. A score above 5 indicates insomnia and poor sleep quality [29]. In a study conducted on pregnant women in Tabriz, Iran, the reliability of this tool was reported 0.84 [27].

A modified PSAS was used to measure pregnancy anxiety. Its short version contains 11 questions. The answer to each question varies from not at all (score 1) to very relevant (score 5). Higher scores indicate a higher level of anxiety and there is no cut-off point. In a study conducted in Tabriz, Iran, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was obtained at 0.74 and ICC was obtained at 0.73 [30].

The QOL-GRAV has 9 questions to assess the level of personal experiences of quality of life during pregnancy. Each item is scored based on the Likert scale ranging from not at all (score zero) and completely (score five). In this questionnaire, the first six questions are scored in reverse. Persian version of QOL-GRAV has good validity and reliability, so this tool can be used to assess the quality of life of pregnant women [31].

Data analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS-24 software. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of quantitative data and all variables had normal distribution. Chi-square, Chi-square for trend, and Fisher's exact and independent t tests were used to evaluate the homogeneity of groups in terms of sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the mean scores of quality of life and anxiety among the intervention groups before the intervention and ANCOVA test was used after the intervention by adjusting the baseline score and the age variable. All analyses were performed based on intention-to-treat and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

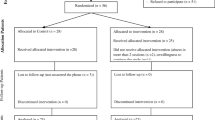

Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram. The socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference among the groups in terms of all socio-demographic characteristics except age variable, the effect of which was controlled by ANCOVA test.

Based on one-way ANOVA before the intervention and ANCOVA after the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference among the study groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference between the study groups based on one-way ANOVA (P = 0.194). After the intervention based on ANCOVA test and by adjusting the baseline score and age variable, the mean score of anxiety in the intervention group 1 [adjusted mean difference (AMD): − 4.54; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) − 6.79 to − 2.28; P < 0.001] and intervention group 2 (AMD: − 3.30; 95% CI − 5.60 to − 0.97; P = 0.033) was significantly less compared to control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two intervention groups after the intervention (P = 0.379) (Table 3).

Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference among the study groups based on one-way ANOVA (P = 0.132). After the intervention, the quality of life score in the intervention group 1 (AMD: 2.55; 95% CI 0.45–4.65; P = 0.012), and intervention group 2 (AMD: 2.72; 95% CI 0.60–4.83; P = 0.007) was significantly higher compared to the control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two intervention groups after the intervention (P = 0.996) (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of this study showed that cognitive–behavioral counseling reduced anxiety and improved quality of life but had no effect on sleep quality.

The results of studies conducted by Edinger and Sampson [32] on patients at Durham Medical Center showed that cognitive–behavioral therapies improve sleep quality. Also, the results of a study conducted by Reybarczyk [33] on older adults show that CBT is effective in reducing sleep onset time and improving sleep quality. In another study by Querstret et al. [34] about the effect of CBT on adults, there were no significant differences between groups in self-reported sleep quality. Thus, the results are controversial. Cognitive–behavioral counseling with or without Citrus aurantium essential oil did not have an effect on quality sleep, which is probably due to differences in participants, the virtual holding of some sessions due to COVID-19 disease, as well as the lack of regular and correct exercise at home. Along with primary insomnia and physical conditions, pregnancy-specific sleep problems may impede treatment. It seems that CBT may not be sufficient for women with high PSQI scores. Also, observing sleep restrictions and scheduling might be difficult during pregnancy. There is a need to perform high-quality trials for sleep-related interventions during pregnancy and implement effective programs in standard prenatal care [35]. Citrus aurantium essential oil did not have an effect on sleep quality in our study. Based on the literature review, the effect of Citrus aurantium on sleep quality has been less studied than other essential oils, such as lavender, bergamot, and chamomile [36]. In comparison with the previous studies, the results may be due to the pregnancy-specific conditions and socio-demographic differences of the participants [37, 38]. It is recommended that future studies focus more on the above-mentioned items.

The results showed that cognitive–behavioral counseling had a positive effect on pregnancy anxiety. Many studies confirm the role of psychological therapies as a way to reduce anxiety and choose natural childbirth in pregnant women. For example, the results of a study showed that CBT methods reduce anxiety in nulliparous women [39]. Another study reported that both trait anxiety and state anxiety decreased in pregnant women who underwent Teasdale’s Cognitive Therapy [40]. Firouzbakht et al. [41] also showed in their study that pregnancy education and psychological support of women during childbirth reduce anxiety and labor pain and reduce the frequency of interventions, such as episiotomy and emergency cesarean section. Another study revealed that psychological education in nulliparous women with severe fear of childbirth reduces the choice of cesarean section and increases satisfaction with the experience of childbirth [42].

Cognitive reconstruction, also known as rational empiricism, helps people identify the flow of anxious thoughts using logical reasoning for practical testing the content of their anxious thoughts against the reality of their life experiences. In other words, they test the probability of occurring that something that will happen in reality [43]. Thus, cognitive assessment of events affects the response to those events and will pave the way for changing cognitive activity [44].

The results of this study showed that cognitive–behavioral counseling has a positive effect on quality of life. In explaining these results, it can be stated that pregnancy is associated with stress, which can affect the quality of life of pregnant women. Thus, cognitive–behavioral counseling helps pregnant women manage stress, identify stressful situations, and then teach strategies to cope with these situations. CBT equips participants with a variety of integrated techniques that they can use to reduce stress and improve quality of life [45]. Through training muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing, people are taught to control their daily stress, and through negative thinking and thinking power, people are taught to recognize and control their negative cognitive symptoms [46].

The effect of cognitive–behavioral counseling with aromatherapy on sleep quality in pregnant women was examined for the first time. In this regard, standard and valid questionnaires were used to assess the consequences and the native language of pregnant women was used during counseling sessions to communicate more with women and these cases can be considered as the study strengths. All women participating in this study were literate, so this can affect the generalizability of results in illiterate women. Among the limitations, we didn’t create a cognitive–behavioral counseling-only group; more methodological work is needed in future studies. Also, we only included pregnant women with a gestational age of 20–24 weeks. The future studies should be conducted on women in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. It is recommended to hold several sessions of cognitive–behavioral counseling for those who support these women (husbands and other family members). Also, the effect of CBT-I should be also assessed in future studies. It is also recommended to investigate the effect of cognitive–behavioral counseling on other populations such as women of childbearing age.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the study, it is concluded that cognitive–behavioral counseling with or without aromatherapy with Citrus aurantium essential oil can reduce anxiety and improve quality of life during pregnancy, but had no effect on the quality of sleep of pregnant women and its subdomains. Further studies are required to develop a protocol to guide pregnant women with sleep problems.

References

VandenBerg KA. State systems development in high-risk newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit: identification and management of sleep, alertness, and crying. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2007;21(2):130–9.

Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. Medical physiology e-book. 3rd ed. New York: Elsevier; 2016.

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):179–89.

Cunningham F, Leveno K, Bloom S, Spong CY, Dashe J. Williams’s obstetrics. 25th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

Sharma S, Franco R. Sleep and its disorder in pregnancy. Wisconsin Med J. 2004;103(5):48–52.

Okun ML, Coussons-Read ME. Sleep disruption during pregnancy: how does it influence serum cytokines? J Reprod Immunol. 2007;73(2):158–65.

Sharma SK, Nehra A, Sinha S, Soneja M, Sunesh K, Sreenivas V, Vedita D. Sleep disorders in pregnancy and their association with pregnancy outcomes: a prospective observational study. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(1):87–93.

Mardasi F, Tadayon M, Najar S, Haghighizadeh MH. The effect of foot massage on sleep disorder among mothers in postpartum period. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;16(73):19–28.

Dritsa M, Deborah DC, Verreault N, Balaa C, Kudzman J, Khalifé S. Sleep problems and depressed mood negatively impact health-related quality of life during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13:249–57.

Bagheri L, Sarshar N. Check outbreak of depression and risk factors on pregnant woman. National conference on health psychology. J Ahvaz Azad Univ Med Sci. 2012;18:75–88.

Deklava L, Lubina K, Circenis K, Sudraba V, Millere I. Causes of anxiety during pregnancy. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;9(205):623–6.

Ryding EL, Wirefelt E, Wangborg IB, Sjogren B, Edman G. Personality and fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(7):814–20.

Miller MA, Mehta N, Clark-Bilodeau C, Bourjeily G. Sleep pharmacotherapy for common sleep disorders in pregnancy and lactation. J Chest. 2019;157(1):184–97.

Rygh JL, Sanderson WC. Treating generalized anxiety disorder: evidenced-based strategies, tools, and techniques. New York: Guilford Press; 2004.

Carney C, Edinger JD. Multimodal cognitive behavior therapy, insomnia: diagnosis and treatment. London: Informa Healthcare; 2010.

van der Zweerde T, Bisdounis L, Kyle SD, Lancee J, van Straten A. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of long-term effects in controlled studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;48: 101208.

Trentin AP, Santose ARS, Miguel OG, Pizzolarti MG, Yunes RA, Calixto JB. Mechanisms involved in the antinociceptive effect in mice of the hydroalcohlic extract of siphcamphylus verticillatus. J Pharm Phrmacol. 1997;49:567–72.

Marline S, Laraine K. Foundation of aromatherapy, vol. 22. 7th ed. New York: Lippincott; 2008. p. 3–9.

Her J, Cho MK. Effect of aromatherapy on sleep quality of adults and elderly people: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2021;1(60): 102739.

Ko LW, Su CH, Yang MH, Liu SY, Su TP. A pilot study on essential oil aroma stimulation for enhancing slow-wave EEG in sleeping brain. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–1.

Pultrini Ade M, Galindo LA, Costa M. Effects of the essential oil from Citrus aurantium L. in experimental anxiety models in mice. Life Sci. 2006;78(15):1720–5.

Ozgoli G, Esmaeili S, Nasiri N. The effect oral of orange peel on the severity of symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Reprod Fertil. 2011;12(2):123–9.

Cheraghi J, Valadi A. Effects of anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory component of limonene in herbal drugs. Iran J Med Aromat Plant. 2009;26(3):415–22.

Mohammadi Payandar F, Tafazoli M, Mazloum SR, Salari R, Vagheie S, Sedighi T. The effect of aromatherapy with Citrus aurantium essential Oil on anxiety in women at risk of preterm labor. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2022;24(12):88–97.

Namazi M, Akbari SA, Mojab F, Talebi A, Majd HA, Jannesari S. Aromatherapy with citrus aurantium oil and anxiety during the first stage of labor. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(6): e18371.

Arasteh M, Yousefi F, Sharifi Z. Investigation of sleep quality and its influencing factors in patients admitted to the gynecology and general surgery of besat hospital in Sanandaj. Med J Mashad Univ Med Sci. 2014;57(6):762–9.

Effati-Daryani F, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Mohammadi A, Zarei S, Mirghafourvand M. Evaluation of sleep quality and its socio-demographic predictors in three trimesters of pregnancy among women referring to health centers in Tabriz, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Care. 2019;9(1):69–76.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(3):737–40.

Bayrampour N, Nourizadeh R, Mirghafourvand M, Mehrabi E, Mousavi S. Psychometric properties of the pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire-revised2 among Iranian women. Crescent J Med Biol Sci. 2019;6:369–74.

Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Shiri F, Ghanbari-Homayi S. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the iranian version of the quality of life questionnaire for pregnancy. Iran Red Crescent Med. 2016;18(9):e35382.

Edinger JD, Sampson WS. A primary care friendly cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. J Sleep. 2003;26(7):177–82.

Rybarczyk B, Lund HG, Mack G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in older adults: background, evidence, and overview of treatment protocol. Clin Gerontol J. 2013;36(1):70–93.

Querstret D, Cropley M, Kruger P, Heron R. Assessing the effect of a Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)-based workshop on work-related rumination, fatigue, and sleep. Eur J Work Organ. 2016;25(1):50–67.

Bacaro V, Benz F, Pappaccogli A, De Bartolo P, Johann AF, Palagini L, Lombardo C, Feige B, Riemann D, Baglioni C. Interventions for sleep problems during pregnancy: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;50: 101234.

Tang Y, Gong M, Qin X, Su H, Wang Z, Dong H. The therapeutic effect of aromatherapy on insomnia: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;288:1–9.

Arab Firouzjaei Z, Illali ES, Taraghi Z, Mohammadpour RA, Amin K, Habibi E. The effect of citrus aurantium aroma on sleep quality in the elderly with heart failure. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2019;21(1):181–7.

Zeighami R, Jalilolghadr S. Investigating the effect of “Citrus Aurantium” aroma on sleep quality of patients hospitalized in the coronary care unit (CCU). Complement Med J. 2014;4(1):720–33.

Imanparast R, Bermas H, Danesh S, Ajoudani Z. The effect of cognitive behavior therapy on anxiety reduction of first normal vaginal delivery. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2014;22(1):974–80.

Karimi A, Moradi O, Shahoei R. The effect of Teasdale’s cognitive therapy on anxiety reduction during pregnancy. Int J Hum Cult Stud. 2016;Special Issue:1170–80.

Firouzbakht M, Nikpour M, Asadi Sh. The effect of prenatal education classes on the process of delivery. J Health Breeze. 2014;2(1):45–54.

Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, Tokola M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Obstetric outcome after intervention for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women—randomised trial. BJOG. 2013;120(1):75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.

Arch JJ, Dimidjian S, Chessick C. Are exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapies safe during pregnancy? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(6):445–57.

Dobson KS, Dozois DJA. Historical and philosophical bases of the cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Dobson K, editor. Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. p. 3–38.

Flugel Colle KF, Vincent A, Cha SS, Loehrer LL, Bauer BA, Wahner-Roedler DL. Measurement of quality of life and participant experience with the mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16(1):36–40.

Keir ST. Effect of massage therapy on stress levels and quality of life in brain tumor patients—observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(5):711–5.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for support of this trial.

Funding

Tabriz University of Medical Sciences provided funding, but it had no role in the design and conduct of the study, and decision to this manuscript writing and submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the research and technology deputy of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.905). The informed written consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahmani, N., Araj-Khodaei, M., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S. et al. The effect of cognitive–behavioral counseling with or without Citrus aurantium essential oil on sleep quality in pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 21, 337–346 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-023-00451-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-023-00451-7