Abstract

This article examines whether people are motivated to change their life direction at all, who is currently changing their purpose, and whether they prefer the assistance of a digital companion or a professional when changing their purpose. Adults (N = 792, 50.3% women) participated in a survey that addressed these questions. Across all participants, 53.4% said they wanted to change their life direction or were currently working on it, and among those respondents, 56.5% preferred support from a professional or digital companion. Results showed that lower life satisfaction, younger age, and identifying as a woman were associated with a greater likelihood of being motivated to change their purpose and a greater likelihood of actually making an effort to change their purpose, relative to not wanting to change their purpose. In addition, demographic variables helped distinguish participants who preferred support from a professional or a digital companion compared to those who did not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sense of purpose can be described as the extent to which people feel they have personally meaningful goals and directions that guide them through life and lead to life engagement (Ryff, 1989; Scheier et al., 2006). Sense of purpose encompasses both “having a direction in life” as a life aim and greater engagement with life, which refers to the processes and activities one takes in pursuit of a goal or as a means to an end. Rather than viewing an object or event as “having a purpose,” this conceptualization reflects perceiving a lifelong direction that helps to define one’s personal identity and catalyzes them forward. In this way, sense of purpose has been described as the motivational, goal-directed component of leading a meaningful life, distinct from perceptions of whether life makes sense and is coherent, or that one’s life holds significance and matters to others (see e.g., Costin & Vignoles, 2020; Martela & Steger, 2016). Research has shown that sense of purpose is associated with various life outcomes. For example, research links a strong sense of purpose with higher subjective well-being (Gudmundsdottir et al., 2023; Pfund et al., 2022b), better social well-being (Hill et al., 2023a; Pfund et al., 2020), healthier lifestyles and better health strategies (Hill et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020), better physical health (Kim et al., 2022; Willroth et al., 2021), better cognitive health (Boyle et al., 2010; Windsor et al., 2015), and even longevity (Cohen et al., 2016).

Given these benefits, it is valuable to note that people can change on this construct over time. Research has shown that while sense of purpose is a relatively stable individual difference over years (Hill et al., 2015; Hill & Weston, 2019), relative within-person stability is evident across more frequent assessment spans (Pfund et al., 2024). Indeed, it is commonly treated as a relatively stable disposition (Windsor et al., 2015), leading to scholars calling for greater consideration of sense of purpose from a trait-state perspective (Pfund, 2023). Despite this marked rank-order stability individuals do show the capacity to fluctuate in their sense of purpose across years (e.g., Ko et al., 2016) and from day to day (e.g., Kiang, 2012; Ratner et al., 2023) depending on situations and environments. For example, sense of purpose may decline in older adulthood (Hill et al., 2015; Hill & Weston, 2019), potentially due to the loss of work roles and declining health. In addition, research in daily life suggests that the expression of purpose shows intraindividual variability over short periods of time as a function of internal (e.g., neuroticism; Hill et al., 2022) and external factors (e.g., social interactions; Pfund et al., 2022).

The positive consequences of purpose and its malleability have led researchers to call for the development and evaluation of intervention efforts to promote and cultivate sense of purpose and engagement in life (e.g., Pfund & Lewis, 2020). To date, however, it is largely unclear whether people are motivated to change their direction in life at all and who is currently changing their life direction. The present study aimed to fill this gap by first examining the extent to which people are motivated to change purpose, and if so, whether they would prefer assistance from a digital companion, professional assistance, or without external support.

1.1 Motivation to Change Direction in Life

The present study was informed by two different lines of research. Given that the personality literature has been frequently called upon for considering purpose (e.g., Pfund, 2023; Pfund et al., 2024), one line of relevant research is the extant work on people’s goals to change their personality change. Previous research in the field of personality development has shown that many people want to change some aspects of personality; for instance, people most commonly report the desire to increase on traits like extraversion and conscientiousness, and decrease negative emotionality (Hudson et al., 2020; Stieger et al., 2020a, b; Thielmann & de Vries, 2021). Furthermore, there is initial evidence showing that the desire for personality change occurs all over the world (Baranski et al., 2021). Other studies focused on the goals to change moral traits (Sun & Goodwin, 2020; Sun et al., 2023) and character strengths such as creativity, bravery, or gratitude (Gander & Wagner, 2023). Although many people want to change some aspects of their personality, similar studies have not been conducted regarding the motivation to change sense of purpose. While this personality trait work suggests that people may be motivated to change, a purpose in life is a uniquely personal construct, insofar that it helps to define who one is and organize their activities toward a broader aim (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). As such, it remains an open question whether people will be also motivated to change their life direction.

The second line of research informing this current study comes from work on the different phases or stages in behavior change efforts. Several theoretical models offer insights into the different phases or stages people move through when trying to change themselves, from the initial readiness to change, to actual efforts to change, and ultimately maintenance of change. For example, the Rubicon model of action phases (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987) suggests four different phases for how people make decisions: pre-decision, post-decision, action, and post-action. First, before a decision for a change is made, a pre-decision phase takes place in which many different options are considered. Second, the decision to change is made in the post-decision phase, in which the implementation of the chosen goal is planned. Third, the action phase refers to the active pursuit of the change goal. Finally, in the post-action phase people evaluate the results of their goal-oriented behavior.

Another framework, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM; Prochaska et al., 1995), is perhaps the most prominent model of change and highlights five stages that represent incremental increases in preparedness to change (Norcross et al., 2022; Prochaska et al., 1995). While in the precontemplation stage, people are unaware of the consequences of their behavior and resist change, but in the contemplation stage, they are aware of the consequences of their behavior and open to change. In the preparation phase, people show anticipation and willingness to change in the coming months. While in the action stage, people are in the process of changing their behavior. Finally, in the maintenance stage, they want to maintain the new, learned behavior and show persistence rather than backsliding into the previous behavior.

In the present study, the motivation for a change of direction in life was examined in terms of three different phases of change. The categorization was inspired by the above discussed models: (a) having no desire to change purpose; (b) motivation to change purpose; and (c) actual efforts to change purpose. The first phase may be the result of a decision against changing purpose in the pre-decision phase (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987), or may simply reflect a state in which one is unaware of the consequences of not changing one’s direction in life, as is evident in the precontemplation phase (Prochaska et al., 1995). The second phase, having the motivation to change purpose, can be viewed through the lens of the post-decision phase, in which a decision to change is made (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987), or as a combination of the contemplation and preparation stages in the TTM (Prochaska et al., 1995). The third phase, which involves actual efforts to change purpose, is related to the action phase in the Rubicon model (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987) as well as the action stage in the TTM (Prochaska et al., 1995).

1.2 Correlates of the Motivation to Change Direction in Life

There are multiple reasons why people may want to change their direction in life. First, people may want to compensate for a lower level or lack of purpose. Research on personality change goals provides initial evidence for this idea by suggesting that people are more likely to want to improve those personality traits on which they currently score lower (Gander & Wagner, 2023; Hudson & Roberts, 2014; Miller et al., 2019; Quitus et al., 2017; Stieger et al., 2020). Based on this reasoning, lower sense of purpose should be associated with a stronger motivation to change direction in life.

Second, people may want to change purpose because they are dissatisfied with their life. Previous literature from the field of personality development suggests that desires for change are motivated in part by dissatisfaction with areas of life (Baumeister, 1994; Hudson & Roberts, 2014; Stieger et al., 2020a, b). Moreover, research shows that making these changes can help improve wellbeing, insofar that increases on a desired personality trait have been associated with increased life satisfaction with life (Hudson & Fraley, 2016a; Olaru et al., 2023). Consequently, lower satisfaction with life may be associated with a stronger motivation to change direction in life.

Third, age also may correlate with the motivation to change purpose. Initial research findings suggest that personality change goals are common among younger and middle-aged adults. Although change goals appear slightly less prevalent in old age, some older adults were motivated to change some aspects of their personality (Hudson & Fraley, 2016b). However, it is reasonable to assume that younger and older adults in particular are more motivated to change their direction in life compared to middle-aged adults, given that research shows that sense of purpose shows normative increases from young to middle adulthood but often decreases in older adulthood (Hill & Weston, 2019; Hill et al., 2023a; Mann et al., 2021).

Fourth, gender is another potential correlate of the motivation to change. A recent cross-cultural study on personality change goals among college students found that women (64%) reported significantly more attempts to change aspects of their personality than men (57%) (Baranski et al., 2021; but see also Miller et al., 2019). There also is evidence from clinical studies that men are less likely than women to seek help for psychological issues (Liddon et al., 2018; Pattyn et al., 2015) and physical health (Ballering et al., 2023). Based on this work, one would expect women to have greater motivation to change direction in life as compared to men.

1.3 Preference for an Approach to Change Direction in Life

Beyond whether people are motivated to change their direction in life, individual differences are likely with respect to preferred approaches to change purpose. The present study focuses on three different broad ways that people could rely on to help change their direction in life: (a) support from a professional, such as a counselor, coach, or psychologist; (b) support from a digital companion, such as a smartphone app or internet program; (c) no help from a professional or a digital companion. The main goal of this distinction is to primarily distinguish between human support versus non-human, digital support for efforts to change one’s direction in life. Support from a coach is one example of how people can receive human support. Through coaching one can learn methods to help focus on their needs and goals, including their goals for self-change, combined with professional observation of and feedback on their behavior, performance, and learning (Passmore, 2021; Passmore et al., 2013). The goal of coaching thus is to improve and optimize performance, including enhancing and improving social, emotional, and behavioral skills and behaviors to maintain or develop positive social relationships, regulate emotions, and manage goal-directed and learning behaviors. Meta-analyses on coaching effectiveness as well as systematic literature reviews on the determinants of coaching have found that coaching is an effective intervention method (Bozer & Jones, 2018; Grant, 2013; Jones et al., 2016; Sonesh et al., 2015), although effect sizes vary between and within meta-analyses.

In recent decades though, greater attention has been paid to supporting people in their change efforts through digital tools such as a companion app. Digital companion apps support self-change efforts through automatic delivery of small interventions. Although traditional coaching approaches typically use individual or group formats in controlled settings with face-to-face interaction, a digital companion is a powerful way to provide momentary, guided, automated, and tailored information, education, and support remotely in everyday contexts (Allemand & Stieger, 2024). Digital companions can provide the specific type and amount of support at a defined time by adapting to people’s changing internal states and environments (e.g., social opportunities to increase momentary expressions of purpose) (Nahum-Shani et al., 2018). These features of mobile apps can reinforce and sustain change efforts and support people in performing exercises, completing tasks, and training remotely. Recent research in the field of personality development has shown that digital coaching interventions are effective in helping people pursue their personality change goals (Allemand & Flückiger, 2022; Allemand & Stieger, 2024; Stieger et al., 2021; Stieger et al., 2020a, b).

However, not all people seeking change will want the support of a professional or a digital companion for self-change efforts. Individual preferences may be shaped by personal background and available resources. For instance, the preference for a digital companion, as well as the acceptance and use of modern communication technologies, may differ as a function of demographic factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES) and individual factors such as interest in digital technology (Andone et al., 2016; Seifert & Charness, 2022). In general, older adults tend to use digital services less than younger generations. Furthermore, past research suggests women may be more likely to utilize assistance from health professionals (e.g., Briscoe, 1987; Corney, 1990), which may be exhibited here too insofar that men may avoid this route to changing purpose. Finally, it is possible that people with higher SES prefer professional support because they are better educated and have higher incomes and can therefore afford coaching with a physically present coach.

1.4 The Present Study

Given the importance of sense of purpose across multiple life domains, the present study sought to describe which routes people may prefer to catalyze changes in life direction. The present study had two primary research aims. First, it investigated the motivation to change purpose, and how frequently people report being in different stages of change. Based on the past literature, we expected people to be more motivated to change when (a) they report lower sense of purpose, (b) they are more dissatisfied with their life, (c) they are in younger or older adulthood relative to middle-aged adulthood, and (d) identify as women rather than men.

Second, the present study aimed to examine the preference for three approaches to change purpose: professional support, a digital companion, or no external support. This work is more exploratory in nature, as the field is lacking theoretical frameworks for predicting desired approaches for change. However, we expected younger adults to prefer a digital companion, whereas middle-aged and older adults prefer professional assistance. Women may prefer professional assistance more than men, and the same may hold for people with higher SES, given they have greater opportunity to afford professional help.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample and Procedure

In total, 830 participants were recruited, but we excluded 24 participants who had missing values on all variables of interest and 14 participants who had missing values for more than 60% of the variables of interest. The final sample consisted of 792 participantsFootnote 1 (49.7% men; 50.3% women). Participants’ age ranged from 19 to 85 years (M = 50.31; SD = 16.34). Of the participants, 12.4% reported having a high school diploma, 30.0% some post-high school training (e.g., some college, vocational degree), 39.0% a bachelor’s degree, and 17.1% an advanced professional degree (e.g., Master’s degree, MBA). Regarding employment status, 15.6% were currently not working, 11.1% part time, 43.7% full time, 14.6% retired, 1.7% currently studying, 2.0% homemakers, and 11.3% self-employed. Regarding relationship status, 30.7% were single, 42.8% married or in a committed relationship and living together, 6.1% married or in a committed relationship and not living together, and 12.3% divorced. Participants indicated their yearly household income using a 8-point scale ranging from 1 (under 150,000). The mean income was 4.03 (SD = 1.77) which refers to $50,000–74,999. A total of 79.8% of participants identified themselves as White, 10.6% as Black or African American, 4.9% as Asian or Pacific Islander, and 2.9% as Hispanic or Latinx (participants could check multiple options). In general, participants reported a relatively good subjective health (M = 2.72, SD = 1.03) on a scale ranging from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Washington University in St. Louis (IRB ID# 202,304,002; date of approval: 4/4/23). Data was collected from a U.S. sample as part of a broader study examining the associations between sense of purpose, meaning in life, future time perspective, health, and health behaviors in adulthood. Data collection took place in May 2023 using the Prolific panel service. Participants received compensation for their work in line with the “good” pay rates at Prolific, which is currently around $12/hour of work. The only inclusion criteria for the present study were that individuals were 18 + years of age and currently living in the United States. However, we did intentionally over-recruit participants in older adulthood, to ensure a sufficient representation across the adult years.

2.2 Measures

Motivation to change purpose. We used a single-item measure to measure motivation to change purpose (“Are you currently thinking of changing your direction in life?“) with six response options: 1 (I am not currently thinking about changing my life direction), 2 (I would like to change my life direction, but have not done so yet), 3 (I would like to change how I pursue my life direction, but I am not interested in changing the direction itself), 4 (I am currently trying to change my life direction), 5 (I am currently trying to change the way I pursue my life direction), 6 (I do not have a life direction). We employed the language of “life direction” rather than “purpose” to avoid any participant confusion around purpose in life versus whether life has purpose; in so doing, we connect to past sense of purpose measures, which focus on direction as a primary theme (e.g., Hill et al., 2016; Ryff, 1989). Our single-item measure relates to other single-item measures that have been used in the field of personality development to measure change goals (e.g., the single-item measure “Is there an aspect of your personality that you are currently trying to change?” with the response options “yes” or “no”; Baranski et al., 2021). Moreover, the measure relates to the three different stages of change discussed earlier, but additionally differentiates between changing one’s life direction (“end”) versus changing the way to one’s life direction (“means to an end”). For the main analyses, we created a nominal variable with three categories by combining the response options 2 and 3, 4 and 5, 1 and 6 into average scores: 1 (motivation to change purpose), 2 (actual efforts to change purpose), and 3 (having no desire to change purpose).

Preference for an approach to change purpose. Next, participants were asked “Which of the following approaches would you prefer to help you change?” The three response options were: 1 (support from a professional, such as a counselor, coach, or psychologist), 2 (support from a digital companion, such as a smartphone app or internet program), and 3 (without support from a professional or digital companion).

Sense of purpose. Participants completed the Purpose in Life subscale from the Psychological Well-being scale (Ryff, 1989) to measure sense of purpose. Participants rated their level of agreement with the 9 items using a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (to strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.88.

Life satisfaction. Participants also completed the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) to measure life satisfaction. Participants rated their level of agreement with five items using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (to strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.92.

2.3 Analytical Plan

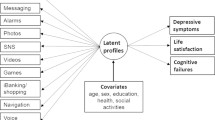

The preregistration of the analyses and hypotheses can be found at Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/vygma)Footnote 2. The analyses were performed in four steps. First, we examined the response distribution for each response options of the two single-item measures. Second, for the primary question of interest, we examined the bivariate associations between the motivation to change purpose with the three categories and sense of purpose, life satisfaction, and demographic variables using analyses of variance (one-way ANOVAs). For the interpretation of eta squared effect sizes, we used the following effect size guidelines (Cohen, 1988): small: 0.01 ≤ η2 < 0.06, medium: 0.06 ≤ η2 < 0.14, large: η2 ≥ 0.14. Third, to examine the unique role of the variables examined in the ANOVAs, we performed multiple regression analyses. Due to the nominal nature of the motivation to change purpose variable with three categories, we used a multinominal logistic regression model to examine the multivariate associations between the motivation to change purpose and sense of purpose, life satisfaction, and demographic variables. In these analyses, the last category (i.e., no desire to change purpose) served as the reference category to compare it with the two other categories (i.e., motivation to change purpose; actual efforts to change purpose). Fourth, we examined the bivariate and multivariate associations between the preference for an approach to change purpose and demographic variables and SES using analyses of variance and a multinominal logistic regression model. In this analysis, the last category (i.e., without support from a professional or a digital companion) served as the reference category.

The regression analyses were conducted in Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. We report exact values for each of the p-values for the regression analyses below allowing the reader to choose their own benchmark for interpretation in lieu of implementing a single strategy to manage Type I error. Materials (i.e., Mplus syntax and additional tables) can be found at OSF (https://osf.io/tvfa3/).

3 Results

3.1 Motivation to Change Direction in Life

The response distribution for the motivation to change purpose is shown in Table 1 using the original six response options and using the new three categories. Almost half of the sample (46.6%) reported having no desire to change purpose, meaning they are not thinking about changing their life direction or they report having no life direction. The other half of the sample indicated that they are motivated to change their purpose or the way they pursue their life direction (27.5%) or are currently working to change their purpose or the way they pursue their life direction (25.9%).

Participant levels of sense of purpose, life satisfaction, and demographic variables as a function of the three categories of motivation to change purpose are shown in Table 2.Footnote 3 Results from analyses of variance showed a significant small effect of the motivation to change purpose on sense of purpose (F(2,787) = 5.73, p =.003, η2 = 0.014, 95% CI [0.002, 0.033]). Post-hoc analyses using the Tukey HSD showed that participants who had no desire to change their purpose reported a significantly higher sense of purpose than participants who wanted to change their sense of purpose (p =.002). A medium sized effect was observed for satisfaction with life (F(2,788) = 48.14, p =.003, η2 = 0.109, 95% CI [0.070, 0.149]). Participants without a desire to change their purpose were significantly more satisfied with their lives than participants who wanted to change their purpose (p <.001) or were currently working on changing their purpose (p <.001). A medium sized effect was also found for age (F(2,789) = 27.26, p <.001, η2 = 0.065, 95% CI [0.035, 0.100]), indicating that participants who wanted to change purpose (p <.001) or who were currently trying to change purpose (p <.001) were on average 8 years younger than those without a desire to change purpose. The motivation to change purpose categories did not differ by gender χ2 (2) = 1.24, p =.539. A small effect was found for education (F(2,780) = 6.11, p =.002, η2 = 0.015, 95% CI [0.002, 0.035]), insofar that participants with a motivation to change (p =.006) and those making actual efforts to change purpose (p =.022) reported significantly lower levels in education compared to those participants without a desire to change purpose. Finally, a small effect was also found for income (F(2,773) = 5.12, p =.006, η2 = 0.013, 95% CI [0.001, 0.032]). The only significant mean-level difference occurred between participants who were currently trying to change their purpose and those who were not (p =.008), wherein individuals who had no desire to change their purpose had slightly higher income.Footnote 4

The results of the multinominal logistic regression models are shown in Table 3, with all variables included as predictors. For these analyses, no desire to change purpose reflects the reference category. Therefore, negative estimates can be interpreted as evidence that higher scores on variables of interest reflect a greater likelihood to have no desire to change purpose compared to the other category of interest. First, life satisfaction, age, and gender significantly differentiated who was more likely to be motivated to change purpose versus who did not feel the need to change purpose. Lower life satisfaction (p <.001), younger age (p <.001), and identifying as a woman (p =.008) were associated with a greater likelihood of being motivated to change purpose (Table 3). Second, sense of purpose, life satisfaction, age, and gender helped to distinguish participants with actual efforts to change purpose from those who did not feel the need to change purpose. Higher sense of purpose (p =.003), lower life satisfaction (p <.001), younger age (p <.001), and identifying as a woman (p =.016) were associated with a greater likelihood for actual change efforts (Table 3).

Notably, sense of purpose was now linked to a greater likelihood of actual change efforts, counter to ANOVA analyses and the means presented in Table 2. To explore this finding, we conducted follow-up regressions with and without including life satisfaction in the models. These analyses suggested that the inclusion of this variable led to the change in direction for the sense of purpose association. Accordingly, it is likely that the contrary findings for sense of purpose in the multinomial regressions resulted from the high association between life satisfaction and sense of purpose (r =.48, p <.001).

3.2 Preference for an Approach to Change Direction in Life

For these analyses, we excluded participants (n = 51) who reported having no desire to change purpose but still responded to the question about the preference for an approach to change life direction. The response distribution for the preference for an approach to change purpose is shown in Table 1. From those who reported they are currently trying to change purpose or that they would like to do so, the plurality of participants indicated that they would like to change purpose or do so without support from a professional or digital companion (43.5%). Additionally, 34.3% reported a preference for support from a professional and 22.2% from a digital companion.

The levels of demographic variables as a function of the three categories of preference for an approach to change purpose are shown in Table 4. Results showed a marginal significant age effect on the preference for an approach to change purpose (F(2,419) = 2.98, p =.052, η2 = 0.014, 95% CI [0.000, 0.041]). However, post-hoc analyses using the Tukey HSD did not show significant age differences between the three categories. The preference for an approach to change purpose categories did not differ by gender χ2 (2) = 2.00, p =.368. A small effect was found for education (F(2,419) = 6.42, p =.002, η2 = 0.030, 95% CI [0.005, 0.066]) with a higher level of education for those who preferred a professional as compared to those who preferred a digital companion (p =.005) or neither a professional nor a companion (p =.008). Finally, a small effect was also found for income (F(2,416) = 3.99, p =.019, η2 = 0.019, 95% CI [0.000, 0.049]). Post-hoc analyses using the Tukey HSD showed a higher average income for those who preferred support from a professional as compared to those who preferred neither a professional nor a companion (p =.014).

The results of the multinominal logistic regression models are shown in Table 5. In these models, participants who reported wanting to change without support from a professional or a digital companion constitute the reference category. Age, gender, education, and income helped to distinguish the professional support category from the no support category. Younger age (p =.005), identifying as a woman (p =.035), higher education (p =.020), and higher income (p =.045) were associated with a greater likelihood to prefer support from a professional (Table 5). Finally, age marginally (p =.058) differentiated who was more likely to prefer a digital companion versus who did not prefer support from either a professional or a digital companion. Specifically, younger age was associated with a greater likelihood to prefer support from a digital companion (Table 5).

4 Discussion

Researchers have called for the development of intervention efforts to promote and cultivate purpose and engagement in life (e.g., Hill et al., 2023; Pfund & Lewis, 2020). However, before developing these interventions, it is first essential to examine whether people are motivated to change their life direction at all and which methods they would prefer. This study has contributed to this goal in four important ways. First, the present results suggest that more than half of the respondents were motivated to change their purpose or were already working on it. Second, life satisfaction, age, and gender served to distinguish individuals motivated to change and their preferred method. Third, among those people who reported they are currently trying or would like to change purpose, more than half of the respondents preferred either support from a professional or from a digital companion, although a plurality did not desire support. Fourth, again age and gender helped distinguish these categories, but education level also played a role in method preference.

4.1 Motivation to Change the Direction in Life is Widespread

The present study was the first to explore people’s motivation to change purpose. This work has shown that in the current large but nonrepresentative sample, a substantial amount of people (53.4%) want to change or are currently working on changing their life direction. In comparison to other change goals, such as the desire to change some aspects of one’s personality (e.g., Baranski et al., 2021; Hudson et al., 2020), less people reported a desire to change their purpose. One reason may be that, as noted earlier, one’s purpose in life may be more personally determined and thus people are less willing to change. Some support on this front comes from our findings that individuals with no desire to change reported the highest levels for sense of purpose.

Another possibility results from differences in measurement tools compared to studies of personality change motivation. Previous work on personality change goals typically ask people about their motivation to change personality traits using measures such as the Change Goals BFI (C-BFI; Hudson & Roberts, 2014) or the Big Five Trait-Change Goal Inventory (BF-TGI; Robinson et al., 2015). Another approach is to directly ask people whether they are currently trying to change an aspect of their personality and then to quantify the collected open-ended descriptions of desired change goals (Baranski et al., 2017, 2021). However, these measures fail to account for how people who report desires to change personality traits may be at different motivational phases or stages. Thus, the present work makes an important contribution by linking purpose change motivation to different stages or phases of behavior change (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987; Prochaska et al., 1995) and considering three phases: (a) no desire to change purpose; (b) motivation to change purpose; and (c) actual efforts to change purpose.

Consistent with our predictions and previous work on personality change goals (e.g., Baranski et al., 2021; Hudson & Fraley, 2016b; Olaru et al., 2023), individuals who were less satisfied with their lives, who were younger, and who identified as women were more likely to indicate that they were motivated to change their purpose or were already in the process of changing purpose. As shown in Table 2, individuals with a higher sense of purpose were less motivated to change, although this finding did not hold in the multinomial regression models. This lack of significance is unlikely to be due to multicollinearity between sense of purpose and life satisfaction, given their moderate association. Accordingly, it appears that life satisfaction may be a more critical factor than sense of purpose for understanding who wishes to change their life direction. Life satisfaction is a comprehensive and general evaluation of the present and past life, while the sense of purpose reflects what we want to do in the present and future in order to progress toward long-term aims. The present findings may support the claim that people tend to seek or work on purpose adjustment to reduce their dissatisfaction with life. Accordingly, lower life satisfaction may trigger or increase the desire for a change of purpose, whereas a lower sense of purpose does not have the same motivating effect as dissatisfaction with life. These findings provide a strong corollary with the personality change literature, and may speak to a broader desire that those adults dissatisfied with their lives are more likely to wish change in general. Future research should explore this prediction by considering life satisfaction as a predictor of motivation to change across multiple constructs.

4.2 Preference for Professional Assistance Over a Digital Companion

A significant number of respondents who were motivated to change their purpose or were already working on it (56.5%) preferred support from either a professional or a digital companion, compared to making this change on their own. The use of smartphones with text-messaging services and mobile applications for intervention efforts is becoming increasingly popular in psychology and other disciplines (e.g., Allemand & Flückiger, 2022; Allemand & Stieger, 2024; Marsch et al., 2014). Despite the increasing acceptance and use of modern communication technologies for self-help change efforts, it was interesting to see that 34.3% preferred a professional rather than a digital companion in their efforts to change their direction in life in comparison to 22.2% who preferred support from a digital companion. The topic of changing direction in life is most often a very sensitive and personal topic that may require “real” communication with a professional instead of receiving guidance by a digital companion. It is also possible that a digital companion that connects people with a professional would increase the preference for support from digital services.

Furthermore, in line with our expectations, younger, women, higher educated, and higher income individuals in particular preferred support from a professional over no support. The significant gender effect in the regression results (but not in percentage distribution) fits with previous research showing that women are more likely than men to seek the help of health professionals (e.g., Briscoe, 1987; Corney, 1990). Younger age tended to be the only, albeit marginally significant predictor of a greater likelihood of preferring support from a digital companion than no support. This finding underscores that intervention efforts for changing life direction may need to be tailored to a specific lifespan stage, and technological savvy, as younger adults likely have more experience with digital technology than older adults.

4.3 Practical Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

The present study and our approach to measure motivation to change purpose have several practical implications. First, as a prerequisite for the development of purpose intervention programs, it is important to have estimates of the number of people who are generally interested in changing purpose. The present results show that the desire for change is present in quite a lot of people, but that not all people are at the same stage. Second, the distinction into at least three different phases of change is of practical importance because intervention efforts directed at people who are already working to change the direction in life might look somewhat different in terms of structure and activities than intervention efforts directed at people who are motivated to change their purpose but have not yet taken steps in that direction and who need guidance and support to change purpose. Third, the identification of psychological and demographic characteristics of people who desired to change direction in life is informative for future intervention efforts. For example, purpose interventions could target groups with certain psychological and/or demographic characteristics such as age, or knowledge of sense of purpose could be incorporated into individualized intervention planning and counseling. The results show that younger adults, for example, are more likely to prefer the support of a digital companion than older adults, while women rather prefer a professional assistance as compared to a digital companion.

The present study is limited in ways that should promote future research. This first study to examine the motivation to change the direction in life was cross-sectional. Longitudinal work is needed to investigate how purpose changes within individuals as they transition from one phase or stage to the next. For example, it would be interesting to investigate whether people’s sense of purpose decreases when they decide to change their goals, or whether a low sense of purpose makes them realize that they want to change it. Second, although the present study, with a relatively large sample, had a wide age range and sufficient variation in important variables, such as SES, the next step would be to conduct representative surveys to further explore the motivation to change purpose and the need for support in motivating one to change one’s life direction or the way one pursues one’s life direction. Third, given the highly subjective nature of purpose change goals, the findings of the study were based on self-reports. However, this leaves open the possibility that participants responded on the basis of what would be socially desirable. Future research may enrich the self-report data of the psychological correlates of the motivation to change purpose with observer reports by close informants (e.g., friends and family members) and behavioral measures. Similarly, qualitative data may enrich the current research with investigations into the individual reasons for motivation to change purpose and the reasons for preferred practices in change efforts. Future research is also needed to examine motivation to change purpose in relation to different ways of human support (e.g., psychotherapy, coaching), and non-human, digital support (e.g., websites, mobile apps). Fourth, the current sample consisted solely of participants recruited through an online participant recruitment portal, which may bias findings toward individuals with greater technological expertise. As such, the preferences for an app-based program may in fact be even lower in the general population.

5 Conclusion

These caveats aside, the current study provides valuable insights for future intervention efforts to change purpose, including multiple findings of relevance for targeting these programs. As the next step, future longitudinal research is needed to explore whether motivation to change purpose influences purpose development trajectories. One possibility is that those adults who are motivated to change may be more likely to recognize opportunities for doing so. One recent conceptual framework (Hill et al., 2023) points to how large-scale changes may be easier to motivate through shifting more proximal states and habits. However, critical to this model is that individuals first are able to recognize when they feel purposeful and what experience or role is yielding that state. A natural next step for researchers is to consider whether individuals who are motivated to change their purpose are those also more likely to recognize these first steps and opportunities along the way.

Data Availability

Due to IRB restrictions, the data cannot be made public. However, interested researchers can reach out to the last author (E-Mail: patrick.hill@wustl.edu) to get the data. Additional materials (e.g., Mplus syntax and additional tables) can be found at OSF (https://osf.io/tvfa3/).

Notes

A sensitivity analysis (G*Power; Faul et al., 2007) for the primary question of interest indicated that the sample size (N = 792) is sufficient to detect effects of small size for a one-way ANOVA with 3 groups (at 80% power Cohen’s f = 0.11, at 95% power f = 0.14).

In the preregistration, we presented the single-item measure of motivation to change purpose with 5 response options. The sixth response option (“I have no direction in life”) was added shortly before data collection.

The zero-order correlations between sense of purpose, life satisfaction, and demographic variables are shown in OSF Table 1S. The strongest association was found between sense of purpose and life satisfaction (r =.48, p <.001).

The results for the six categories of the motivation to change purpose can be found in OSF Table 2S. In addition, we compared the participants who were not currently thinking about changing their life direction (n = 317) with the participants who stated that they had no direction in life (n = 51). Results have shown that participants who were not currently thinking about changing their life direction reported significantly higher levels of sense of purpose and life satisfaction, higher age and higher income than those participants who stated that they had no direction in life (see in OSF Table 2S).

References

Allemand, M., & Flückiger, C. (2022). Personality change through digital-coaching interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211067782

Allemand, M. & Stieger, M. (2024). Digital coaching to promote and manage change. In: K. Taku & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of changes in human perceptions and behaviors (pp. 309–323). New York: Routledge.

Andone, I. I., Blaszkiewicz, K., Eibes, M., Trendafilov, B., Montag, C., & Markowetz, A. (2016). How age and gender affect smartphone usage. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing: Adjunct.

Ballering, A. V., Hartman, O., Verheij, T. C., R., & Rosmalen, J. G. M. (2023). Sex and gender differences in primary care help-seeking for common somatic symptoms: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 41(2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813432.2023.2191653

Baranski, E. N., Morse, P. J., & Dunlop, W. L. (2017). Lay conceptions of volitional personality change: From strategies pursued to stories told. Journal of Personality, 85(3), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12240

Baranski, E. N., Gardiner, G., Lee, D., Funder, D. C., & Members of the International Situations Project. (2021). Who in the world is trying to change their personality traits? Volitional personality change among college students in six continents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(5), 1140–1156. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000389

Baumeister, R. F. (1994). The crystallization of discontent in the process of major life change. In T. F. Heatherton, & J. L. Weinberger (Eds.), Can personality change? (pp. 281–297). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10143-012

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(3), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208

Bozer, G., & Jones, R. J. (2018). Understanding the factors that determine workplace coaching effectiveness: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1446946

Briscoe, M. E. (1987). Why do people go to the doctor? Sex differences in the correlates of GP consultation. Social Science and Medicine, 25(5), 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(87)90174-2

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,.

Cohen, R., Bavishi, C., & Rozanski, A. (2016). Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274

Corney, R. H. (1990). Sex differences in general practice attendance and help seeking for minor illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 34(5), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(90)90027-2

Costin, V., & Vignoles, V. L. (2020). Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 864–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000225

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2023). Which positive personality traits do people want to change? European Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070231211957

Grant, A. M. (2013). The efficacy of coaching. In J. Passmore, D. B. Peterson, & T. Freire (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of the psychology of coaching and mentoring (pp. 15–39). Wiley Blackwell.

Gudmundsdottir, G. R., Pfund, G. N., Hill, P. L., & Olaru, G. (2023). Reciprocal associations between sense of purpose and subjective well-being in old age. European Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070231176702

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992338

Hill, P. L., & Weston, S. J. (2019). Evaluating eight-year trajectories for sense of purpose in the health and retirement study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1399344

Hill, P. L., Edmonds, G. W., Peterson, M., Luyckx, K., & Andrews, J. A. (2016). Purpose in life in emerging adulthood: Development and validation of a new brief measure. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1048817

Hill, P. L., Turiano, N. A., Spiro, A., & Mroczek, D. K. (2015). Understanding inter-individual variability in purpose: Longitudinal findings from the VA normative aging study. Psychology and Aging, 30(3), 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000020

Hill, P. L., Edmonds, G. W., & Hampson, S. E. (2019). A purposeful lifestyle is a healthful lifestyle: Linking sense of purpose to self-rated health through multiple health behaviors. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(10), 1392–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317708251

Hill, P. L., Klaiber, P., Burrow, A. L., DeLongis, A., & Sin, N. L. (2022). Purposefulness and daily life in a pandemic: Predicting daily affect and physical symptoms during the first weeks of the COVID-19 response. Psychology & Health, 37(8), 985–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1914838

Hill, P. L., Olaru, G., & Allemand, M. (2023a). Do associations between sense of purpose, social support, and loneliness differ across the adult lifespan? Psychology and Aging, 38(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000733

Hill, P. L., Pfund, G. N., & Allemand, M. (2023b). The PATHS to purpose: A new framework toward understanding purpose development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 32(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214221128019

Hudson, N. W., & Fraley, R. C. (2016a). Changing for the better? Longitudinal associations between volitional personality change and psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(5), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216637840

Hudson, N. W., & Fraley, R. C. (2016b). Do people’s desires to change their personality traits vary with age? An examination of trait change goals across adulthood. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(8), 847–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550616657598

Hudson, N. W., & Roberts, B. W. (2014). Goals to change personality traits: Concurrent links between personality traits, daily behavior, and goals to change oneself. Journal of Research in Personality, 53, 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.08.008

Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Chopik, W. J., & Briley, D. A. (2020). Change goals robustly predict trait growth: A mega-analysis of a dozen intensive longitudinal studies examining volitional change. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(6), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619878423

Jones, R. J., Woods, S. A., & Guillaume, Y. R. (2016). The effectiveness of workplace coaching: A meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89, 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12119

Kiang, L. (2012). Deriving daily purpose through daily events and role fulfillment among Asian American youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00767.x

Kim, E. S., Shiba, K., Boehm, J. K., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2020). Sense of purpose in life and five health behaviors in older adults. Preventive Medicine, 139, 106172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106172

Kim, E. S., Chen, Y., Nakamura, J. S., Ryff, C. D., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2022). Sense of purpose in life and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health: An outcome-wide approach. American Journal of Health Hromotion, 36(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211038545

Ko, H. J., Hooker, K., Geldhof, G. J., & McAdams, D. P. (2016). Longitudinal purpose in life trajectories: Examining predictors in late midlife. Psychology and Aging, 31(7), 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000093

Liddon, L., Kingerlee, R., & Barry, J. A. (2018). Gender differences in preferences for psychological treatment, coping strategies, and triggers to help-seeking. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12147

Mann, F. D., DeYoung, C. G., & Krueger, R. F. (2021). Patterns of cumulative continuity and maturity in personality and well-being: Evidence from a large longitudinal sample of adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 109737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109737

Marsch, L., Lord, S., & Dallery, J. (2014). Behavioral healthcare and technology: Using science-based innovations to transform practice. Oxford University Press.

Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology, 13(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017152

Miller, T. J., Baranski, E. N., Dunlop, W. L., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Striving for change: The prevalence and correlates of personality change goals. Journal of Research in Personality, 80, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.03.010

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nahum-Shani, I., Smith, S. N., Spring, B. J., Collins, L. M., Witkiewitz, K., Tewari, A., & Murphy, S. A. (2018). Justin-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: Key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8

Norcross, J. C., Cook, D. M., & Fuertes, J. N. (2022). Patient readiness to change: What we know about their stages and processes of change. In J. N. Fuertes (Ed.), The other side of psychotherapy: Understanding clients’ experiences and contributions in treatment (pp. 73–97). American Psychological Association.

Olaru, G., van Scheppingen, M. A., Stieger, M., Kowatsch, T., Flückiger, C., & Allemand, M. (2023). The effects of a personality intervention on satisfaction in 10 domains of life: Evidence for increases and correlated change with personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(4), 902–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000474

Passmore, J. (2021). The coaches’ handbook: The complete practitioner guide for professional coaches Routledge.

Passmore, J., Peterson, D. B., & Freire, T. (2013). The psychology of coaching and mentoring. In J. Passmore, D. B. Peterson, & T. Freire (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of the psychology of coaching and mentoring (pp. 1–11). Wiley Blackwell.

Pattyn, E., Verhaeghe, M., & Bracke, P. (2015). The gender gap in mental health service use. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, 1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1038-x

Pfund, G. N. (2023). Applying an allportian trait perspective to sense of purpose. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(4), 1625–1642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00644-4

Pfund, G. N., & Lewis, N. A. (2020). Aging with purpose: Developmental changes and benefits of purpose in life throughout the lifespan. In P. L. Hill, & M. Allemand (Eds.), Personality and healthy aging in adulthood (pp. 27–42). Springer.

Pfund, G. N., Brazeau, H., Allemand, M., & Hill, P. L. (2020). Associations between sense of purpose and romantic relationship quality in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(5), 1563–1580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520903807

Pfund, G. N., Hofer, M., Allemand, M., & Hill, P. L. (2022a). Being social may be purposeful in older adulthood: A measurement burst design. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(7), 777–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.11.009

Pfund, G. N., Ratner, K., Allemand, M., Burrow, A. L., & Hill, P. L. (2022b). When the end feels near: Sense of purpose predicts well-being as a function of future time perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 26(6), 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891203

Pfund, G. N., Burrow, A. L., & Hill, P. L. (2024). Purpose in daily life: Considering within-person sense of purpose variability. Journal of Research in Personality, 109, 104473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2024.104473

Prochaska, J. O., Norcross, J. C., & DiClemente, C. C. (1995). Changing for good. Harper Collins.

Quintus, M., Egloff, B., & Wrzus, C. (2017). Predictors of volitional personality change in younger and older adults: Response surface analyses signify the complementary perspectives of the self and knowledgeable others. Journal of Research in Personality, 70, 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.08.001

Ratner, K., Li, Q., Zhu, G., Estevez, M., & Burrow, A. L. (2023). Daily adolescent purposefulness, daily subjective well-being, and individual differences in autistic traits. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24, 967–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00625-7

Robinson, O. C., Noftle, E. E., Guo, J., Asadi, S., & Zhang, X. (2015). Goals and plans for big five personality trait change in young adults. Journal of Research in Personality, 59, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2015.08.002

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Scheier, M. F., Wrosch, C., Baum, A., Cohen, S., Martire, L. M., Matthews, K. A., Schulz, R., & Zdaniuk, B. (2006). The Life Engagement Test: Assessing purpose in life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9044-1

Seifert, A., & Charness, N. (2022). Digital transformation of everyday lives of older Swiss adults: Use of and attitudes toward current and future digital services. European Journal of Ageing, 19(3), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00677-9

Sonesh, S. C., Coultas, C. W., Lacerenza, C. N., Marlow, S. L., Benishek, L. E., & Salas, E. (2015). The power of coaching: A meta-analytic investigation. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory Research and Practice, 8(2), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2015.1071418

Stieger, M., Eck, M., Rüegger, D., Kowatsch, T., Flückiger, C., & Allemand, M. (2020a). Who wants to become more conscientious, more extraverted, or less neurotic with the help of a digital intervention? Journal of Research in Personality, 87, 103983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103983

Stieger, M., Wepfer, S., Rüegger, D., Kowatsch, T., Roberts, B. W., & Allemand, M. (2020b). Becoming more conscientious or more open to experience? Effects of a two-week smartphone-based intervention for personality change. European Journal of Personality, 34(3), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2267

Stieger, M., Flückiger, C., Rüegger, D., Kowatsch, T., Roberts, B. W., & Allemand, M. (2021). Changing personality traits with the help of a digital personality change intervention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(8). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2017548118. Article e2017548118.

Sun, J., & Goodwin, G. P. (2020). Do people want to be more moral? Psychological Science, 31(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619893078

Sun, J., Wilt, J., Meindl, P., Watkins, H. M., & Goodwin, G. P. (2023). How and why people want to be more moral. Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12812Advance online publication.

Thielmann, I., & de Vries, R. E. (2021). Who wants to change and how? On the trait-specificity of personality change goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(5), 1112–1139. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000304

Willroth, E. C., Mroczek, D. K., & Hill, P. L. (2021). Maintaining sense of purpose in midlife predicts better physical health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 145, 110485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110485

Windsor, T. D., Curtis, R. G., & Luszcz, M. A. (2015). Sense of purpose as a psychological resource for aging well. Developmental Psychology, 51(7), 975–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000023

Acknowledgements

We thank Payton Rule for her help in preparing study materials and collecting data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich. This work was supported the Velux Stiftung / Velux Foundation, Zurich, Switzerland (no. 1723).

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA conceived the study, performed the statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. GNP conceived the study and critically revised the manuscript. PLH conceived the study, interpreted the results, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Washington University in St. Louis (IRB ID# 202,304,002; date of approval: 4/4/23). Informed consent was obtained prior to participation in the study.

Preregistration

The preregistration of the analyses and hypotheses can be found at Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/vygma).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allemand, M., Pfund, G.N. & Hill, P.L. Motivation to Change Direction in Life with a Little Help from a Digital Companion or a Professional Assistance. Int J Appl Posit Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00170-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00170-5