Abstract

Promoting social skills in addition to teaching curricular content is challenging for elementary-school teachers. Teaching methods that implicitly foster social skills could support teachers and students alike. Peer influence and social learning, as a mediating peer-influence mechanism, could be beneficial. If peers can show their social skills in class, students with lower social skills could adopt their skillset. An intervention study investigating the peer influence effect of cooperative learning on the development of social skills was conducted with 558 students (Mage = 8.66; 49,3% female) of 26 classes. Over the course of four weeks Cooperative Learning was implemented daily in intervention classes to determine the effects of peer influence as well as additional effects of Cooperative Learning on the development of social skills. The results suggest that students with low social skills can benefit from Cooperative Learning if they are taught in highly socially skilled classes. The article discusses possibilities to enrich Cooperative Learning to benefit all students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A common demand in society and politics is that social skills should be fostered in educational institutions (UNICEF, 2012). Such demands are consistent with research findings of recent decades. Indeed, there is ample research investigating the importance of social skills for academic success (Frogner et al., 2022), mental health (Newcomb et al., 1993), and social participation (Frostad & Pijl, 2007). Within the social skills deficit model, Asher et al. (1982) postulated that the lack of social skills is associated with social exclusion. Yet, even if social skills are uniformly considered a key success factor in children’s development, there seems to be no uniform definition (Rose-Krasnor, 1997). The consensus is that social skills are a multifactorial construct and are a prerequisite for overcoming social problems and successfully cultivating social relationships (Berg et al., 2017; Gresham & Elliott, 2008; Rose-Krasnor, 1997). In line with the findings that social skills are essential for healthy social, psychological, and professional development, there are a variety of approaches to promoting social skills through manual-based support programs (Mooij et al., 2020) or peer-assisted teaching methods (Ginsburg-Block et al., 2006). In a meta-analysis, January et al. (2011) emphasized that social skills training in early elementary education can be particularly successful. Although social skills training and research are promising and comprehensive, teachers may face difficulties in finding the time and monetary resources to incorporate extracurricular competencies, such as social skills, into their everyday teaching alongside the regular curriculum (Miyamoto et al., 2015). Nevertheless, schools already offer extensive resources to foster social skills. On the one hand, teachers and peers can serve as positive models aiding social learning (Bandura, 1971). On the other hand, students can be taught complex social skills in small steps. In particular, students who do not acquire sufficient social skills outside of school can try out newly observed social behaviors in the protective space of school. Given the limited time teachers have to integrate extracurricular programs concerning social skills in daily class, an efficient way to support students in acquiring social skills is needed. The current study aims to evaluate whether the exposure to other children with high social skills can improve social skills among children with lower initial social skills, consistent with the mechanisms of peer influence (Brown et al., 2008). In addition, this study aims to examine cooperative learning (CL) as a method for guiding and enhancing peer influence in the contect of teaching social skills. Consistent with the mechanisms of social learning (Bandura, 1971), CL could create a learning space that makes other students’ socially skilled behavior visible and thus adoptable.

In the following, we outline the influence of peers on the development of socially skilled behavior, while focusing on integrating the concept of peer influence into CL as an environment for social learning that might implicitly benefit students.

1.1 Peer Influence as a Resource in Developing Social Skills

As children progress from childhood to adolescence, their caregivers’ influence becomes less important while their peers’ influence increases (Lam et al., 2014). Previous research has shown that, particularly with regard to the development of antisocial and aggressive behavior, peer behavior has an influence on individual development (Müller et al., 2017; Prinstein & Dodge, 2008; Rohlf et al., 2016). There are isolated findings suggesting underlying mechanisms of peer influence in the development of prosocial behavior. For example, Hofmann and Müller (2018) investigated whether individuals can be prevented from developing antisocial behavior by their classmates’ prosocial behavior and concluded that a prosocial peer community could be a protective factor impeding the development of antisocial behavior. In addition, Busching and Krahé (2020) found that peer influence fostered by social learning mechanisms increased the development of individuals’ prosocial behavior. First, they found that individuals experienced greater increases in prosocial behavior if their classmates had higher prosocial behavior levels. This class-level effect was moderated by initial individual differences. These findings lend credibility to the call by Laursen and Veenstra (2023), who have implored scholars to look at peer influence beyond the limited and negatively connoted notions of peer contagion and peer pressure and regard peer influence as a resource in fostering skills. Farmer et al. (2011) emphasized that peer influence is not an uncontrollable process but can and should be channeled by teachers. To illustrate the points at which peer influence can be shaped, the following analysis presents a possible underlying mechanism of action that could take effect in peer influence.

Concerning the underlying mechanisms, different approaches have been postulated. Brown et al. (2008) has summarized these in a conceptual model of peer influence (Fig. 1). This model discusses several underlying elements that shape the process of peer influence. Brown et al. (2008) based the model on the notion that an event initiates the process of peer influence for an individual. The resulting behavior then in turn influences the further course of event. The loop-shaped process of event–activation of peer influence–outcome is the basis for peer influence. The characteristics of the interaction of individual and contextual factors subsequently influences whether a response and a longer-term outcome are elicited.

Conceptual model of the mechanisms of peer influence (adapted from Brown et al., 2008)

The activation of peer influence depends on timing (Can the exhibited behavior be remembered?), mode (Is there any peer pressure?), intensity (How insistently do peers act?), and consistency (Is there variability in behavior?). Whether and how the activation of peer influence changes depends on different aspects of the interaction of the individual and the context, on individuals’ openness to peer influence, on the salience of influencers, on the relationship dynamics and on the ability/possibility to perform.

When seeking to use peer influence to foster social skills, teachers have the opportunity to help shape this process, as emphasized by Farmer et al. (2011). While children’s openness to peer influence and the relationship dynamics between them are factors located within the children themselves, teachers can determine the salience of certain influential behaviors. In addition, teachers can create the space for students to try out observed behaviors and therefore offer an opportunity to perform.

Within the framework of peer influence, there are evident parallels with the social learning paradigm (Bandura, 1971). The parallels lie in the preconditions for peer influence and social learning, which consist on the one hand in the salience of the peer behavior to be observed and on the other hand in the opportunity of imitating corresponding behavior. These characteristics and the empirical findings (e.g., Busching & Krahé, 2020) emphasize the role of social learning in developing prosocial behavior. The mechanism described and the associated social learning also suggest that social skills could be implicitly fostered in the classroom. To support this conclusion, we present social learning as the basis for peer influence and CL as a concept of enriched social learning below.

1.2 Social Learning as a Basis for Peer Influence

In works that investigate peer influence, social learning (Bandura, 1971) has emerged as one of the underlying processes that explains its mechanisms (Brown et al., 2008). Bandura (1971) postulated that, while behaviors can sometimes be deliberately learned, they are often acquired inadvertently. Social learning processes depend on attentional processes, retention processes, motoric reproduction processes, and reinforcement and motivational processes (Bandura, 1971). Therefore, behaviors can only be learned if learners pay attention to a given behavior and are able to recollect it. Furthermore, learners must have the motoric skillset to reproduce an observed behavior. And finally, learning can be enhanced if models are reinforced for the respective behavior. As the goal of this study is to implicitly foster social skills via peer influence, which is further enriched via CL, several factors need to be considered. First, social skills must be made visible so that they can be perceived and internalized by students. Second, opportunities must be created in which students can try out the observed behavior for themselves. These situations should give teachers the opportunity to reinforce appropriate behavior. There are evident parallels between the four processes of model learning (Bandura, 1971) and the previously presented factors that foster peer influence (Brown et al., 2008). Accordingly, social learning can be understood as a central mechanism of peer influence. The school context offers teachers the opportunity to structure social interactions and thus the necessary social skills being shown. This can be achieved by implementing CL (Hank et al., 2022). School tasks in a cooperative setting can be designed to require certain social skills due to the nature of the tasks and the chosen social form without the showing of social skills seeming choreographed or forced (Johnson & Johnson, 1994). Teachers can then provide feedback on successful social behaviors in CL, while students have the opportunity to observe different models of socially skilled behavior and thus expand their own behavioral repertoire.

Although school classes are social settings in themselves and therefore a place in which peer influence occurs (Müller & Zurbriggen, 2016), the extent of required prosocial behavior, cooperation, and self-control varies from class to class, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Just as peers have been found to influence the development of antisocial behavior, peers influence individuals’ behavior via the mechanisms of social learning (Bandura, 1971; Busching & Krahé, 2020). As these processes occur naturally in classroom settings, this process might be used to foster social skills. The extent to which social skills can be developed through CL is discussed below.

1.3 Cooperative Learning as a Setting for Social Learning

CL is a form of group work for which certain basic criteria are ensured. Johnson and Johnson (2002) postulated five basic elements of CL: positive interdependence, individual accountability, face-to-face promotive interaction, group processing, and social skills. Johnson and Johnson (2002) argued that CL—as defined in the learning-together approach—can only be regarded as cooperative if the five basic principles are relevant to the task. Accordingly, CL can only be considered cooperative if social skills, which are the skills this study seeks to develop, are also part of the cooperative task. Social skills are thus a prerequisite for CL, but they are also fostered implicitly and explicitly by CL (Lanphen, 2011). CL assignments are often structured in the three-step think-pair-share sequence.

From the viewpoint of social learning, the structure of CL provides individuals with noteworthy models of social skills that initiate communication and cooperation. Students get the chance to witness the advantages of social skills in this learning setting. Furthermore, CL provides the opportunity to reproduce and practice certain social skills.

From an empirical perspective, van Ryzin et al. (2020) have found that CL enhances prosocial behavior among middle school students, while Mendo-Lázaro et al. (2018) have confirmed beneficial effects of CL on team-working skills in higher education. They emphasize, that teachers need to provide adequate structures to enable students to participate in CL units (Mendo-Lázaro et al., 2018). Ginsburg-Block et al. (2006) examined the effects of CL on students’ social skills (friendships, cooperative behavior, conflict resolution skills, etc.) in first through sixth grades using 36 group studies of peer-assisted learning. They found weak weighted effect sizes of d = 0.28. Social indicators were positively influenced by a high degree of autonomy, strong structuring, individualized curricula, and the use of group contingency procedures.

Beyond the effects on social skills, CL has been found to improve the social inclusion of excluded children (Garrote & Dessemontet, 2015; Hank et al., 2023; Weber & Huber, 2020). Findings of positive effects of CL on academic achievement (Slavin, 1983) lend support to the teaching method itself, but are not taken into account in this study.

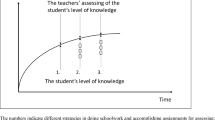

With the aim of improving social interactions between children and fostering social skills, we developed a specific variant of CL (Hank et al., 2023). This study investigates whether a form of CL that focuses on improving contact experiences and that intentionally does not focus on academic achievement can be beneficial in supporting the effects of peer influence on social skills development. Since CL enhances contact experiences but also requires social skills, it is a promising topic to research. A possible effects model can be found in Fig. 2.

While peers’ skills influence individuals’ social skills development, this effect is likely to be enhanced by the use of CL. In CL, all students have the opportunity to observe social skills, as a CL classroom setting requires more social skills than, for example, a frontal classroom setting. In particular, students with low social skills are given the opportunity to expand their social behavioral repertoire. Consequently, this study aims to evaluate CL as an effective strategy for enhancing and creating social learning opportunities.

1.4 The Current Study

To investigate whether peers actually influence the development of social skills and whether this influence can be increased by implementing CL, the present intervention study was designed to investigate two hypotheses. The hypotheses account for the notion that social skills should be considered in a context-specific manner (Rose-Krasnor, 1997). Based on evidence that social skills exist as a multifactorial construct (e.g., Gresham & Elliott, 2008; Hank & Huber, 2023; Rose-Krasnor, 1997), this paper considers social skills in the form of their subskills when evaluating the success of CL in developing social skills. Accordingly, the following hypotheses refer to social skills as an overall construct. We test the hypotheses at the subskill level which are derived from the German version of the Social Skill Improvement System Rating Scales (SSIS-RS; Gresham & Elliott, 2008). The SSIS-RS comprises the following subskills: communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, engagement, and self-control.

The first hypothesis, which is based on evidence concerning peer influence on prosocial behavior (e.g., Busching & Krahé, 2020), relates to the class composition of social skills. The higher the average social skills in a class, the more likely it is that individual social skills will increase. (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, since children with low social skills have a particular potential to expand their repertoire, we could expect to find an interaction with average class skills (Hypothesis 1.1).

The study was designed to evaluate whether learning opportunities in the form of CL are able to enhance the effects of peer influence on social skills. Based on this, we hypothesized that students benefit more from peer influence in terms of acquiring social skills when CL is implemented. The second assumption is that children in classes with high overall levels of social skillsbenefit more in terms of individual development of social skills when they engage in CL (Hypothesis 2). Again, children with low baseline skills are expected to benefit more from socially skilled classes in CL (Hypothesis 2.1).

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The intervention study, which used a waitlist control-group design comprised a sample of n = 585 students (49.3% female). The average age was M = 8.66 (SD = 0.77) The sample was nested in 26 classes (52,0% third grade, 48.0% fourth grade) of 8 German elementary schools in the region North-Rhine-Westphalia. There were 13 classes in the intervention group; the others constituted the control group. To avoid bias in the evaluation of peer influence effects through CL, we only included the control group in the analyses for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 1.1. We considered the entire sample when assessing Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 2.1.

The sample was made up of schools from both rural and urban regions. Overall, the schools attracted students of medium socioeconomic status. The catchment areas had neither an extremely high nor an extremely low socioeconomic status. All classes had students with an immigrant background. We could not record the specific places where students and/or their families had migrated from due to data protection rules. All participating schools registered for the project voluntarily. They were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups according to their previous experience in CL. A declaration of consent from the parent or legal guardian was enclosed for all participating students.

2.2 Intervention Material

CL was implemented by the class teachers. Class teachers received training on the teaching method specifically developed for this study. After receiving two days of training, they conducted one unit of CL per day over the course of four weeks. Each unit followed a specific structure provided by a standardized toolbox (available in German: www.sozius-projekt.de). The SOZIUS project created a form of CL that adapted the widely known think-pair-share design (Cooper et al., 2021) for use in a five-step scenario (see Hank et al., 2022) to ensure that the form of CL implemented focused on a social setting. Each unit took place in groups of four to five students. Group constellations lasted for a week and changed at the beginning of each week. Each unit followed the same five-step structure. First, students were asked to verbalize their current mood to their respective group of four to five students. This meant students were able to respect each other’s daily emotions while working on an assignment. The second step, think, consisted of timed individual work. This provided students with preparation time for the third step. The third step, pair, was conducted in pairs or groups of two to three students. Students exchanged ideas, had the time to ask questions, and prepared for the fourth step. The share step took place within the core group. Students either presented joint results or their partners’ ideas from the pair exchange. Finally, the teacher concluded the CL unit with the whole class by discussing the assignments’ results with the whole class.

The version of CL followed the basic criteria of the method postulated by Johnson and Johnson (2002). When establishing an adapted version of CL, the researchers also considered the characteristics of optimal contact. Criteria for optimal contact were originally established in the intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954) and further augmented by Pettigrew and Tropp (2006). They consist of the following criteria: equal status, common goal, possibility for informal contact, positive interdependence/intergroup cooperation, support of authorities, quality, regularity, protected environment and self-disclosure. The five-step-structure enables teachers to adapt their CL so that it focuses on contact experiences and social interactions and therefore more on social skills. More detailed instructions for this intervention can be found in the supporting information (Intervention design_E2).

2.3 Design

For this study, we used data from the SOZIUS project funded by BMBF (the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research). We conducted a longitudinal intervention study with a wait control group and three measurement points. The intervention was implemented from November to December 2019, after a two-day teacher training workshop in September/October 2019. Following the training, teachers had a few weeks of preparation time to get acquainted with the CL toolbox. After this, the intervention was implemented. Over the course of four weeks, teachers conducted one unit of CL per day. The intervention was accompanied by weekly changes to classroom seating arrangements. By working in ever-changing groups, children gained different contact experiences, especially with children with whom they usually might not interact. The development of social skills was measured at three time points. The first measurement point was immediately before the teacher training (pre-intervention), one was after the intervention (post-intervention), and one was two to three months after the intervention (follow-up) to check for longterm effects. The study design can be seen in more detail in Table 1.

3 Measures

3.1 Individual Level of Social Skills

To determine the individual level of social skills, we used the German translation (Hank & Huber, 2023) of the Social Skill Improvement System Rating Scales (SSIS-RS; Gresham & Elliott, 2008). The questionnaire allows children to self-assess their social skills. The social skills domain of SSIS-RS consists of 46 items on a four-point Likert scale and comprises the following subscales: communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, engagement, and self-control (Gresham & Elliott, 2008). A self-report instrument was chosen to identify changes in social skills that might go beyond social skills in a class setting or that might be less likely to be observed by teachers, parents, and peers. The German SSIS-RS was validated for students between 8 and 12 years of age. Writing about the English-language version, Gresham et al. (2010) found that interrater reliability between teachers and students was only low to moderate, especially for subscales that did not describe externally shown behaviors such as communication. For the German translation, the reliability of subscales for the student version were considered sufficient to high (0.67 ≤ ω ≤ 0.85). For multilevel analysis, individual scale means were calculated for each measurement point.

3.2 Peer Level of Social Skills

The German SSIS-RS (Gresham & Elliott, 2008) was also considered when calculating the context scores. To determine the contextual value of social skills, we calculated the average level of the respective social subskill in the class. Following a common procedure in peer influence research (e.g., Nenniger, 2022), we accounted for the individual value of the respective social subskill in the context value of the class, in order to consider the fact that the individual partly shapes the class environment (Nenniger, 2022). Consequently, we calculated a context score for each subscale of social skills for T1. All context scores were z-standardized before being included in the multilevel models.

3.3 Data Preparation and Analysis

We accounted for the nested data structure by applying multilevel analysis (Hosoya et al., 2014). The data were nested in the following structure: social skills over time (time level: L1) of students (individual level: L2), who in turn are part of a class community (class level: L3). Considering the nested structure, we followed the guidelines for multilevel analyses, for which a sample size of 20 classes is recommended (McNeish & Stapleton, 2016).

For social subskills as measured by the SSIS-RS scale, we calculated means for each time of measurement. We only considered individuals if not more than one item per subscale was missing. If there was more missing data, we excluded the students in question from further analysis. Furthermore, we adjusted the sample by eliminating those children with missing variance (SD = 0) within the SSIS-RS.

To test Hypothesis 1, we accounted for the interaction of time and the initial level of each class skill. For Hypothesis 1.1, we considered the three-way interaction of time, individual initial level, and social skills of the classroom community for the individual subskills. To be able to interpret the triple interaction, we used a graph. This shows the students’ development over time, differentiated according to the quartiles of the average initial social skills.

To assess Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 2.1, we used the values of the first measurement point to predict the change at the second measurement point and the third follow-up measurement point. We tested Hypothesis 2 by considering the interaction of initial class skills and group. We evaluated Hypothesis 2.1 using the three-way interaction of individual baseline level, initial class skills, and group.

We conducted all analyses separately for all subskills by employing R Version 4.2.0 (R Core Team, 2022) using R packages lme4 (Bates et al., 2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., 2017). We group-mean centered (Hoffman & Walters, 2022) age and gender and controlled for them in all multilevel analysis. Data and syntax are available under the following link: https://osf.io/cmebu/?view_only=f1ddbbf155b4415ba1a3892fe457dce5.

4 Results

Descriptive data analysis show that the intervention group and control group developed minimally over the course of the intervention. The intervention group had slightly lower self-assessed social skills (Table 2). We found significant differences between the intervention and control group at the first measurement point for the subskills of cooperation (t(444) = 2.83, p =.005, g = 0.27, 95% CI for g [0.08–0.46]) and self-control (t(445) = 2.04, p =.041, g = 0.20, 95% CI for g [0.01–0.39]). Results are presented following the hypotheses of this study.

Hypothesis 1

The higher the average social skills in a class, the more likely it is that individual social skills will increase.

For this analysis, we considered the classes in the control group. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, we found a significant interaction effect between time and initial class skill, which suggests that individual skill is more likely to increase in classes with a low initial level. This effect became significant at the second measurement point for responsibility (β = -0.06, p =.020), engagement (β = -0.06, p =.019), and self-control (β = -0.08, p =.025). At the third measurement point, we found significant interaction effects for cooperation (β = -0.08, p =.013), responsibility (β = -0.06, p <.001), engagement (β = -0.06, p =.014), and self-control (β = -0.10, p =.006). Detailed results can be found in Table 3. The model without interaction effects can be found in the supporting information (Table E1).

Hypothesis 1.1

Students with low social skills especially benefit from classes with high social skills.

Longitudinal multilevel models also showed results contrary to Hypothesis 1.1. The interaction of time, respective initial skill, and initial class skill was significant at the second measurement point for cooperation (β = 0.26, p <.001) and at the third measurement point for communication (β = 0.21, p =.001), cooperation (β = 0.31, p <.001), and responsibility (β = 0.20, p <.001). Detailed results can be found in Table 3. To ease interpretation of the three-way interactions, we provide a graphic in Fig. 3 that shows the development of the social subskills differentiated for classes with high and low social skills, and by the initial quartiles of individual social skills. Visual inspection suggests that the higher the initial skills, the more likely students are to benefit from highly skilled classes. Possible ceiling effects are addressed in the discussion.

Hypothesis 2

Students in socially skilled classes benefit more in terms of individual development of social skills when they engage in CL.

To avoid quadruple interactions, when testing Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 2.1, we predicted social skills at the post and follow-up measurement points based on the pre measurement point. For the second measurement point, we found a significant interaction between group and initial class skill for cooperation (β = 0.74, p <.001). For the third measurement point, we found significant interaction effects for communication (β = 0.81, p <.001) and responsibility (β = 0.86, p <.001). These effects indicate that, in socially more skilled environments, CL can aid in improving certain individual social skills. More detailed results can be found in Tables 4 and 5.

Hypothesis 2.1

Students with low baseline skills are expected to benefit more from socially skilled classes in CL.

To see if children with lower social skills are more likely to benefit from the socially skilled environments in CL, we considered the triple interaction of initial individual social skills, classroom skills, and group. For the second, post-intervention, measurement point, we found a significant triple interaction for cooperation (β = -0.30, p <.001; Fig. 4). For the third, follow-up, measurement point, we found significant triple interaction effects for communication (β = -0.32, p <.001; Fig. 5) and responsibility (β = -0.32, p <.001; Fig. 6) (see Tables 4 and 5). To aid interpretation of the effects, Figs. 4 and 5, and Fig. 6 contrast the interaction effect estimated for classes with high and low social skills. The Figures contrast the estimated case for classes whose social skills are one standard deviation above the sample mean versus the estimated case for classes one standard deviation below the sample mean. Here we see that in the intervention group, students with low scores at the pre-intervention measurement point had higher scores at the post-intervention as well as the follow-up measurement point than those in the control group if their class had high average skills (simulated here by setting the score at one standard deviation above the mean). In contrast, children with high levels of initial skills did not deviate substantially from one another in their descriptive development, irrespective of their class skills.

Development of the cooperation subskill differentiated for context scores. Curves distinguish between intervention and control group CG = control group; IG = intervention group; -1SD = class skill of cooperation at one standard deviation below mean; +1SD = class skill of cooperation at one standard deviation above mean

Development of the communication subskill (pre-intervention to follow-up) differentiated for context scores. Curves distinguish between intervention and control group; CG = control group; IG = intervention group; -1SD = class skill of cooperation at one standard deviation below mean; +1SD = class skill of communication at one standard deviation above mean

Development of the responsibility subskill (pre-intervention to follow-up) differentiated for context scores. Curves distinguish between intervention and control group; CG = control group; IG = intervention group; -1SD = class skill of responsibility at one standard deviation below mean; +1SD = class skill of responsibility at one standard deviation above mean

Accordingly, children with low initial skills especially benefit from the skills of their peers when using CL.

5 Discussion

The hypotheses were partially confirmed. Somewhat contradictory results to the first hypothesis, that postulated that the higher the average social skills within a class were, the more likely students’ social skills would improve, could be found. The negative interaction of time and initial class skill showed that self-reported responsibility, engagement, self-control and cooperation were more likely improved in classes with low social skills. Also deviating from the hypotheses, we found a positive three-way interaction of initial social skills and initial class skills and time for cooperation, communication and responsibility. Visual inspection of the data indicates that students with high social skills tend to benefit more from their highly skilled classes.

For CL, we could not find a general effect on the cultivation of social skills, but we could confirm the hypothesis that students with low initial skills could benefit from CL in socially skilled environments. This effect was only evident for the subskills of communication, cooperation, and responsibility. Considering that social learning (Bandura, 1971) requires models that show a specific behavior or skillset, it is likely that different social subskills are not fostered equally effectively within CL. As CL necessitates communicating and cooperating with interaction partners (Johnson & Johnson, 1994) but not necessarily assertion, deviations between the subskills were to be expected.

This replicates findings by Busching and Krahé (2020), who reported that children with lower prosocial behavior especially benefitted from being in contexts with higher prosocial behavior. In this study, there are findings that point in two directions. In the control group, the children with higher skills are more likely to benefit from their peers if CL is not implemented, but when CL is implemented, however, the students with lower initial skills also seem to benefit.

Hence, this study confirms the results of Mendo-Lázaro et al. (2018), who reported promising findings for university students. Brown et al. (2008) have argued that individuals need the opportunity to repeat behavior learned from peers. CL seems to represent a framework for such learning. According to social learning theory (Bandura, 1971) only skills and behavior that can be observed externally can be obtained from a model and therefore adopted by learners. As not all social skills of the SSIS-RS are observable, deviating results for social subskills are to be expected. This suggests that CL can foster communication, cooperation and responsibility but that additional support may be needed when implementing CL so that all students can benefit from this teaching method. In this context, teachers could focus on giving instructions on specific cooperation or communication tasks that facilitate CL for students who are insecure in cooperative task situations.

The effects, even though they are low, are promising given the short intervention time of four weeks. van Ryzin et al. (2020) found robust effects for the development of prosocial behavior when applying an intervention over the course of two years. Compared to that, small doses of CL daily over the course of four weeks offer relatively limited social learning opportunities. Furthermore, we might have found clearer results if we had only accounted for individuals’ closest peers. Bandura (1971) pointed out that people are more likely to learn from likeable models with whom they can identify. This is why some research in the field of peer influence takes the closer peer group into account (e.g., Nenniger et al., 2021). On the other hand, Burton et al. (2003) found that children are more susceptible to peer influence from peers whom they are not close to when cheating in tests. In any case, future research should weight the social network of each child when taking peers’ social skills into account to control for the effects of closeness to learning models. Furthermore, explicit instructions on social behavior have not been a part of the established form of CL. Mendo-Lázaro et al. (2018) discussed instructions on how to be successful in teamwork as essential to achieve teamworking skills with cooperative methods for university students. Elementary school students are likely to benefit from similar instructions. The findings indicate that with certain adaptations and longer and denser episodes of CL, children might benefit from peer influence universally.

5.1 Limitations

Although the results of this study are promising, there are several limitations that should be addressed. From a methodological perspective, the number of classes on L3 of the multilevel analysis of each individual group (IG vs. CG) was small. For Hypothesis 1 in particular, we must emphasize that the number of classes was critically low, since we only had 13 classes while 20 classes are discussed as necessary (McNeish & Stapleton, 2016). This study focused on evaluating CL as a tool for fostering social skills and not solely on confirming the effects of peer influence. Hence, the group size was not ideal for testing Hypothesis 1 about general peer influence effects. Future research should confirm the stability of the effects with a more representative sample. Additionally, ceiling effects of the SSIS-RS might have obscured clearer intervention effects (see Table 2.). For students with high initial skills at the pre-intervention point, the development of social skills should be interpreted cautiously.

From an educational perspective, the intervention time was probably too short. Weber and Huber (2020) recommend planning long-term interventions to observe successful CL in fostering social inclusion. Especially because social learning is based on implicit retention processes and the need for both motoric reproduction and reinforcement processes (Bandura, 1971), learning processes likely take longer than four weeks. For all students to benefit equally from CL as an opportunity to develop social skills, such programs should be implemented over the long term.

Peer influence, too, may need a longer duration of intervention and thus a higher dose. Studies investigating effects of peer influence have observed the development of certain skills over the course of one to two years (Busching & Krahé, 2020; Nenniger, 2022). Notably, since peer influence is a time-dependent process (Brown et al., 2008), effects triggered by peer influence may have been initiated but would have taken more time to produce measurable changes. The findings at the follow-up measurement point seem to be more promising, which supports the notion that peer influence takes more time to unfold.

Furthermore, it is possible that elementary-school teachers are more influential for students’ social skills development than peers. Wullschleger et al. (2020) have found that teachers’ feedback is essential in social settings and influences students’ social acceptance by peers (Nicolay & Huber, 2021; Wullschleger et al., 2020). The notion that teachers’ feedback might mitigate peers’ influence seems evident given that teachers legitimate the social setting in which the socially skilled behavior is supposed to be shown. Because of the importance of reinforcement in social learning (Bandura, 1971) it would be beneficial if teacher feedback in future studies is monitored on the one hand and targeted on the other hand in order to support the effect of cooperative learning. Possible effects of teacher feedback on the development of social skills might also explain the favorable effects for students with higher social skills, who would be more likely to receive feedback on their social skills when only peer influence without CL is taken into account. For future research, CL could be reinforced by a uniform scheme of feedback on specific social actions to strengthen the fostering of social skills (e.g. Tootling; Cihak et al., 2009).

5.2 Implications for Further Research and Practical Use

Beyond that, further research should establish whether effects are caused by the exposure to a change in seating arrangements. While a general increase of social skills in a class can be explained by a CL intervention, more detailed information might be found when investigating specific seating patterns in class. Considering the fact that some children have isolated positions within the class (Webster & Blatchford, 2015), the effects of being exposed to a new neighbor and their skills in class might be substantial. Social skills development could be due to the exposure to new interaction partners.

In a practical implementation of CL, it should be borne in mind that students might feel insecure when having to interact with unfamiliar children. If this is the case, it is important to support the children transitioning from a fixed class structure to a more flexible one. Specific rules for contact and widening the behavior repertoire for interactive situations should be considered, especially if classes are inexperienced with CL. Consequently, longitudinal intervention studies that compare CL and a combination of CL and specific explicit support for social skills could be insightful when developing a version of CL that most students can benefit from in terms of fostering social skills. CL seems to help children on several social dimensions. It appears to form a more secure learning environment for socially insecure children (Weber & Huber, 2023) and aids the social inclusion of excluded children (Hank et al., 2023). It appears to be most effective when implemented on a regular and long-term basis. For practical use, we therefore recommend investing in establishing CL in elementary schools to use social learning and intergroup contact effectively to improve students’ social situations and social skills.

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice (Unabridged, 25th anniversary ed.). Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Asher, S. R., Renshaw, P. D., & Hymel, S. (1982). Peer relations and the development of social skills. In S. G. Moore, & C. R. Cooper (Eds.), NAEYC: Vol. 206. The Young child (pp. 137–158). National Association for the Education on Young Children.

Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting Linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

Berg, J., Osher, D., Same, M., Nolan, E., Benson, D., & Jacobs, N. (2017). Identifying, defining, and measuring social and emotional competencies. American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/identifying-defining-and-measuring-social-and-emotional-competencies-december-2017-rev.pdf.

Brown, B. B., Bakken, J. P., Ameringer, S. W., & Mahon, S. D. (2008). A comprehensive conceptualization of the peer influence process in adolescence. In M. J. Prinstein, & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Duke series in child development and public policy. Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents (pp. 17–44). Guilford.

Burton, B. A., Ray, G. E., & Mehta, S. (2003). Children’s evaluations of peer influence: The role of relationship type and social situation. Child Study Journal, 33, 235–255.

Busching, R., & Krahé, B. (2020). With a little help from their peers: The impact of classmates on adolescents’ development of prosocial behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(9), 1849–1863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01260-8 .

Cihak, D. F., Kirk, E. R., & Boon, R. T. (2009, December). Effects of classwide positive peer ‘tootling’ to reduce the disruptive classroom behaviors of elementary students with and without disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 18(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-009-9091-8.

Cooper, K. M., Schinske, J. N., & Tanner, K. D. (2021). Reconsidering the share of a think-Pair-Share: Emerging limitations, alternatives, and opportunities for research. CBE Life Sciences Education, 20(1), fe1. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-08-0200.

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Wien. https://www.R-project.org/.

de Mooij, B., Fekkes, M., Scholte, R. H. J., & Overbeek, G. (2020). Effective components of social skills training programs for children and adolescents in nonclinical samples: A multilevel meta-analysis. CLINICAL CHILD and FAMILY PSYCHOLOGY REVIEW, 23(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00308-x.

Farmer, T. W., McAuliffe Lines, M., & Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: The role of teachers in children’s peer experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006 .

Frogner, L., Hellfeldt, K., Ångström, A. K., Andershed, A. K., Källström, Å., Fanti, K. A., & Andershed, H. (2022). Stability and change in early social skills development in relation to early school performance: A longitudinal study of a Swedish cohort. Early Education and Development, 33(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1857989 .

Frostad, P., & Pijl, S. (2007). Does being friendly help in making friends? The relation between the social position and social skills of pupils with special needs in mainstream education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250601082224.

Garrote, A., & Dessemontet, R. S. (2015). Social participation in inclusive classrooms: Empirical and theoretical foundations of an intervention program. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 14(3), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.14.3.375 .

Ginsburg-Block, M. D., Rohrbeck, C. A., & Fantuzzo, J. W. (2006). A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept, and behavioral outcomes of peer-assisted learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98; Jg. 2006-11-01(4), 732–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.732.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS): Rating scales Manual. NCS Pearson.

Gresham, F. M., Elliott, S. N., Cook, C. R., Vance, M. J., & Kettler, R. (2010). Cross-informant agreement for ratings for social skill and problem behavior ratings: An investigation of the Social skills Improvement System-Rating scales. Psychological Assessment, 22(1), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018124.

Hank, C., & Huber, C. (2023). Soziale Kompetenzen Im Selbstbericht Bei Kindern Der Primarstufe. Diagnostica, 69(4), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000318.

Hank, C., Weber, S., & Huber, C. (2022). Potenziale des Kooperativen Lernens bei der Förderung sozialer Integration. Die Unterrichtsmethode des Integrationsförderlichen Kooperativen Lernens (IKL). Vierteljahresschrift Für Heilpädagogik Und Ihre Nachbargebiete (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2378/vhn2022.art05d.

Hank, C., Weber, S., & Huber, C. (2023). Die Rolle des Kooperativen Lernens bei der Förderung sozialer Integration: Eine Interventionsstudie. Unterrichtswissenschaft Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-023-00174-1.

Hoffman, L., & Walters, R. W. (2022). Catching up on multilevel modeling. Annual Review of Psychology, 73, 659–689. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-103525.

Hofmann, V., & Müller, C. M. (2018). Avoiding antisocial behavior among adolescents: The positive influence of classmates’ prosocial behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 68, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.013.

Hosoya, G., Koch, T., & Eid, M. (2014). Längsschnittdaten Und Mehrebenenanalyse. Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 66, 189–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-014-0262-9.

January, A. M., Casey, R. J., & Paulson, D. (2011). A meta-analysis of classroom-wide interventions to build social skills: Do they work? School Psychology Review, 40(2), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087715.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1994). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (4.th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2002). Learning together and alone: Overview and meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 22(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/0218879020220110.

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest Package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

Lam, C. B., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 85(4), 1677–1693. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12235.

Lanphen, J. (2011). Kooperatives Lernen und Integrationsförderung: Eine theoriegeleitete Intervention in ethnisch heterogenen Schulklassen. Univ., Diss.—Marburg. Texte zur Sozialpsychologie: Bd. 10. Waxmann.

Laursen, B., & Veenstra, R. (2023). In defense of peer influence: The unheralded benefits of conformity. Child Development Perspectives, 17(1), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12477.

McNeish, D. M., & Stapleton, L. M. (2016). The effect of small sample size on two-level model estimates: A review and illustration. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9287-x.

Mendo-Lázaro, S., León-Del-Barco, B., Felipe-Castaño, E., Polo-Del-Río, M. I., & Iglesias-Gallego, D. (2018). Cooperative team learning and the development of social skills in higher education: The variables involved. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01536.

Miyamoto, K., Huerta, M. C., & Kubacka, K. (2015). Fostering social and emotional skills for well-being and social progress. European Journal of Education, 50(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12118.

Müller, C. M., & Zurbriggen, C. L. A. (2016). An overview of classroom composition research on social-emotional outcomes: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 15(2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.15.2.163.

Müller, C. M., Hofmann, V., & Arm, S. (2017). Susceptibility to classmates’ influence on delinquency during early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(9), 1221–1253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616653475.

Nenniger, G. (2022). Classroom influence—Do students with high autistic traits benefit from their classmates’ social skills? Frontiers in Education, 7, Article 971775. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.971775.

Nenniger, G., Hofmann, V., & Müller, C. M. (2021). Gender differences in peer influence on autistic traits in special needs schools-evidence from staff reports. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 718726. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.718726.

Newcomb, A. F., Bukowski, W. M., & Pattee, L. (1993). Children’s peer relations: A meta-analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin, 113(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99.

Nicolay, P., & Huber, C. (2021). Wie Schulleistung Und Lehrkraftfeedback die soziale Akzeptanz beeinflussen: Ergebnisse Einer Experimentalstudie. Empirische Sonderpädagogik, (1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:23568.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

Prinstein, M. J., & Dodge, K. A. (Eds.). (2008). Duke series in child development and public policy. Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. Guilford.

Rohlf, H., Krahé, B., & Busching, R. (2016). The socializing effect of classroom aggression on the development of aggression and social rejection: A two-wave multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 58, 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.05.002.

Rose-Krasnor, L. (1997). The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development, 6(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00097.x.

Slavin, R. E. (1983). When does cooperative learning increase student achievement? Psychological Bulletin, 94(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.3.429.

UNICEF (2012). Global evaluation if life skills education programmes United Nations Children’s Fund. https://gdc.unicef.org/resource/global-evaluation-life-skills-education-programmes-2012.

van Ryzin, M. J., Roseth, C. J., & Biglan, A. (2020). Mediators of effects of cooperative learning on prosocial behavior in middle School. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 5(1–2), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-020-00026-8.

Weber, S., & Huber, C. (2020). Förderung sozialer Integration Durch Kooperatives Lernen – Ein systematisches review. Empirische Sonderpädagogik, 12, 257–278. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:21611.

Weber, S., & Huber, C. (2023). Empirische Arbeit: Die Wirkung Von Kontakten auf die soziale Unsicherheit Von Schülerinnen Und Schülern. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 70(3), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.2378/peu2023.art14d.

Webster, R., & Blatchford, P. (2015). Worlds apart? The nature and quality of the educational experiences of pupils with a statement for special educational needs in mainstream primary schools. British Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 324–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3144.

Wullschleger, A., Garrote, A., Schnepel, S., Jaquiéry, L., & Moser Opitz, E. (2020). Effects of teacher feedback behavior on social acceptance in inclusive elementary classrooms: Exploring social referencing processes in a natural setting. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101841.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by “Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF)” within the project “SOZIUS” (funding indicator 01NV1739, duration 01.02.2018–31.01.2021). Open science framework: Data and syntax can be viewed under https://osf.io/cmebu/?view_only=f1ddbbf155b4415ba1a3892fe457dce5

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1:

Longitudinal multilevel analysis (Hypothesis 1) of each subskill of social skills measured by the SSIS RS without interaction effects

Supplementary Material 2:

Intervention design of CL

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hank, C., Huber, C. Do Peers Influence the Development of Individuals’ Social Skills? The Potential of Cooperative Learning and Social Learning in Elementary Schools. Int J Appl Posit Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00151-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00151-8