Abstract

The current study considers the effects of the Chinese low arousal emotion Foreign Language Peace of Mind (FLPOM) and the medium-to-high arousal emotion of Foreign Language Enjoyment (FLE) on the performance of 400 Chinese and 502 Moroccan English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners. The database consists of two merged datasets collected with the same instruments from learners with comparable profiles for English. The data on Chinese EFL learners was collected and used in Zhou et al. (Applied Linguistics Review, 2023a) while the data on Moroccan EFL learners was used in Dewaele and Meftah (Journal of the European Second Language Association, 2023); Dewaele et al. (Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 2023a). The comparison revealed that all students reported higher levels of FLE than FLPOM. Moroccan students scored significantly higher on FLPOM and FLE than their Chinese peers. They also had significantly higher scores on the FLE Personal dimension. Finally, FLPOM was more strongly associated with performance than FLE among the Moroccan EFL learners, confirming the pattern in Zhou et al. (Applied Linguistics Review, 2023a). FLPOM did explain slightly more variance in the performance of Chinese EFL learners. Pedagogical implications are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) introduced the concept of Foreign Language Enjoyment (FLE) alongside Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (FLCA) after becoming aware of Positive Psychology and after realising that it is crucial to consider both positive and negative emotions in foreign language (FL) learning. Analysis of quantitative and qualitative data collected through an online questionnaire from 1746 FL learners from all over the world revealed that membership of a particular global-regional group (Europeans, Asians, North Americans, South Americans, Arabs) was one of the learner-internal variables that had a significant effect on levels of FLE and FLCA (though the effect size was very small). North Americans reported the highest levels of FLE and the lowest levels of FLCA while Asian participants reported the lowest levels of FLE and the highest levels of FLCA. Later research on Chinese English Foreign Language learners partly confirmed the pattern: Chinese students reported higher levels of FLCA but similar levels of FLE (Jiang & Dewaele, 2019). However, few differences emerged in the sources of FLE and FLCA and in their effects on academic achievement (Botes et al., 2020b, 2022a, 2022b). Further research showed that FLCA is more strongly linked to learners’ personality while FLE is more dependent on contextual variables, mainly the teacher (see Dewaele, 2022 for an overview).

The fact that all FL learners experience various levels of FLE and FLCA which affect their performance in similar ways does not preclude the existence of other emotions which may in fact have a more powerful effect (Li & Han, 2022). Following this line of thought, Zhou et al. (2023a) introduced a new FL learner emotion, Foreign Language Peace of Mind (FLPOM) alongside FLE in a research design to establish which was the best positive predictor of performance among Chinese EFL learners. FLPOM, which is drawn from the Chinese cultural context, and FLE are both situated toward the positive pole on the valence continuum but they differ in terms of arousal/activation: FLPOM is a low-arousal emotion (Lee et al., 2013) while FLE is a medium-to-high arousal emotion (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). Zhou et al. (2023a) reasoned that since Chinese EFL students are part of a collectivist culture where the expression of low-arousal emotions is typically favoured -in contrast with people socialized in Western cultures where individualism and high-arousal emotions are typically preferred (Chen et al., 2015; Lim, 2016; Novin et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2020)- FLPOM would be a stronger predictor of Chinese EFL performance than FLE. This turned out to be the case.

The present study continues this avenue of investigation, considering two different collectivist cultures, namely China and Morocco. In so doing, it answers the call issued in Andringa and Godfroid (2020) to pay more attention to learners outside Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) societies and to increase the diversity of contexts and samples in order to allow more generalizability. The comparison of two non-WEIRD samples of EFL learners thus allows us “to make Applied Linguistics less WEIRD and, with that, a bit more fair and inclusive” (p. 140). We are not aware of studies that focused specifically on the effect of geographical/cultural background on FL learner emotions. To operationalise cultural values, we refer to Hofstede et al. (2010) for whom culture reflects collective mental programming. The authors distinguish six dimensions: Power distance, Masculinity, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long Term Orientation, Individualism and Indulgence. They calculated means for these dimensions for a large number of countries, including China and Morocco. Since FL learner emotions are most likely to be influenced by the dimensions Individualism versus Collectivism and Indulgence versus Constraint, the between-country comparison in the literature review will be limited to these two dimensionsFootnote 1.

Newly collected data from 502 Moroccan EFL learners based in Morocco will be compared with existing data on FLPOM and FLE from 400 Chinese EFL learners based in China which were collected and analysed in Zhou et al. (2023a). The aim is to establish to what degree these two positive emotions are experienced by Moroccan and Chinese learners and which have the strongest association with self-reported EFL performance.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Positive Psychology in Applied Linguistics

The introduction of Positive Psychology in applied linguistics by MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012) led to a more holistic approach considering both positive and negative learner emotions (Dewaele et al., 2019; Macintyre et al., 2019). The aim of Positive Psychology is not to focus exclusively on what goes wrong in life but also to acknowledge what goes well (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). In applied linguistics this meant a move away from an exclusive focus on the deleterious effects of anxiety in the classroom to include the beneficial effects of positive emotions. Fredrickson’s (2001) ‘Broaden-and-build’ theory proved a particularly useful basis for understanding how negative and positive emotions shape learning. Whereas negative emotions cause a narrowing of focus resulting in limited learning, positive emotions allow learners to broaden their “momentary thought-action repertoires and build their enduring personal resources, ranging from physical and intellectual resources to social and psychological resources” (Fredrickson, 2001, p. 219). MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012) pointed out that the role of positive and negative learner emotions had been underestimated in applied linguistics and argued that they “may be the key to the motivational quality of the imagined future self” (p. 193).

2.2 Foreign Language Enjoyment

Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) introduced the concept of Foreign Language Enjoyment (FLE). They argued that FLE requires sustained intellectual effort and can thus be distinguished from the more superficial and transient pleasure, which is nothing more than an agreeable feeling. They defined FLE as:

A complex emotion, capturing interacting dimensions of the challenge and perceived ability that reflect the human drive for success in the face of difficult tasks […] enjoyment occurs when people not only meet their needs, but exceed them to accomplish something new or even unexpected. (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2016, pp. 216–217)

Although they did not mention arousal explicitly, the full concentration needed to overcome a challenge implies at least a medium level of arousal. Extremely high levels of FLE result in a state of flow (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2022).

To examine the relationship between FLE and Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (FLCA), Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) gathered data from a large international sample of FL using their newly developed FLE scale (21 items) and a short scale of FLCA (8 items), adapted from the 33-item FLCAS (Horwitz et al., 1986). They found that FLE and FLCA were moderately negatively correlated which meant they could be considered to be independent dimensions. This moderate negative relationship was confirmed in a recent meta-analysis of 56 studies (and 96 effect sizes) by Botes et al. (2022a).

Dewaele and MacIntyre (2016) used exploratory factor analysis on their original database in order to determine the factorial structure of FLCA and FLE. The FLCA items loaded on a first factor (FLCA), while the 21 FLE items loaded on two different factors: FLE Social and FLE Private. FLE Social reflected enjoyment originating in the support of peers and teacher while FLE Private reflected self-centred enjoyment. Responding to calls for shorter and psychometrically solid scales, Botes et al. (2021) re-analysed Dewaele and MacIntyre’s (2014) database to construct and validate the Short Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (S-FLES). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis allowed them to identify three factors underlying FLE: teacher appreciation (FLE Teacher), Personal FLE and Social FLE. The authors concluded that the S-FLES demonstrated good reliability, good validity and good internal consistency of the three factors and the global FLE. The scale also demonstrated strong convergent and divergent validity.

Research into sources of FLE have revealed it to be partly related to learner-internal variables such as skill level (with more advanced learners reporting more FLE) (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014; Dewaele & Meftah, 2023, 2024) and more strongly to learner-external variables such as teacher behaviours (Elahi Shirvan et al., 2021; Dewaele, 2022).

2.3 Foreign Language Peace of Mind

Zhou et al. (2023a) adapted the concept of Peace of Mind, which refers to a state of peacefulness and harmony (Lee et al., 2013) to a FL environment. FLPOM was defined as “an indicator of psychological well-being in collectivist cultures” (p. 8). The FLPOM scale was developed and validated using two samples of Chinese high school EFL students: a sample of 158 participants for an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a sample of 441 participants for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The scale consists of eight items and has a single-factor structure. In a follow-up study, Zhou et al. (2023b) found that Chinese EFL students’ cognitive engagement mediated the relationship between FLE, FLPOM and EFL performance. A competitive psychological climate in the classroom weakened the mediation effect of cognitive engagement on FLE and achievement, but did not affect the mediation effect of cognitive engagement on FLPOM and achievement. The authors argue that FLPOM allows learners to gain individual resources and to maintain strong engagement in a highly competitive environment.

2.4 The Relationship Between FLE and FLPOM

The first study to examine the relationship between FLE and FLPOM was Zhou et al. (2023a). The authors used the Chinese version of the FLE scale which comprises 11 items and 3 dimensions (FLE-Private, FLE-Teacher and FLE-Atmosphere) (Li et al., 2018) and their own FLPOM scale. FLPOM and FLE were significantly positively correlated (r = .70, p < .0001), which represents a large effect size. This indicated that high levels of FLE were linked to high levels of FLPOM and that the two positive emotions tend to co-occur in Chinese EFL classrooms. However, regression analyses revealed that the effect of FLE on self-perceived proficiency became insignificant after FLPOM was controlled for. The model explained 13% of variance, i.e. a small effect size. In an attempt to describe fluctuations in positive and negative learner emotions from the start to the end of their EFL journey, Dewaele and Meftah (2023) adopted a pseudo-longitudinal design using the database on which the current study is based. They found that FLE and FLPOM increased significantly between Beginner and Advanced levels, while FLCA and FL Boredom decreased significantly. This suggests that FLE and FLPOM evolve in similar ways.

2.5 FL Learner Emotions and FL Performance

Meta-analyses have shown that FLCA has a moderate negative effect on FL performance while FLE has a moderate positive effect on Willingness to Communicate and academic achievement (Botes et al., 2020b, 2022a). Recently, researchers have started looking at the combined effect of FL learner emotions on their performance using both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. The cross-sectional study by Li and Han (2022) revealed that FLE was a positive predictor while FLCA and FLB were significant negative predictors of perceived English achievement among 348 Chinese EFL learners. FLCA was found to have a slightly greater impact on academic achievement than FLE in the cross-sectional study by Dewaele et al. (2023a). The authors analysed the same sample of 502 Moroccan EFL learners that is used in the present paper. Latent dominance analysis revealed that FLE was the weakest (positive) predictor of EFL achievement while FLCA and Foreign Language Boredom (FLB) were stronger (negative) predictors. FLCA was also shown to have a stronger effect than FLE on self-perceived proficiency of an international group of 1,039 FL learners in Botes et al. (2022b). This cross-sectional study used polynomial regressions with response surface analysis and revealed non-linear relationships between emotions and self-perceived proficiency. Lower levels of FLCA and higher levels of FLE were associated with higher scores on self-perceived proficiency, but FLCA’s impact on perceived proficiency was stronger than that of FLE.

In one of the first longitudinal studies on learner emotions, Saito et al. (2018) gathered data from 108 Japanese EFL students over the course of one semester and found that FLE, FLCA and motivation had a significant effect on the comprehensibility in English of these learners. The students’ progress was associated with high FLE, low FLCA and strong motivation. Similarly, in a longitudinal study involving 954 junior secondary EFL learners in rural China, Li and Wei (2023) found that the effects of emotions on achievement changed over time. While FLE, FLCA and FLB at Time 1 predicted students’ English achievement at Time 2, FLE emerged as the best and most enduring predictor over time.

What these studies suggest is that learner emotions are highly dynamic and that their effects on performance can change over time. A consistent finding is that positive emotions boost performance while negative emotions act as a drag.

2.6 Moroccan Cultural Context

Moroccan culture is rich and diverse: a melting pot of Amazigh, Arab, African, Jewish and European roots and influences (Njoku, 2006; Oumlil & Balloun, 2017). However, Moroccan politicians have tended to downplay the linguistic and cultural diversity in order to preserve national unity since independence from France in 1956 (Ennaji, 2005). Hofstede’s Country Comparison ToolFootnote 2 indicates that Morocco has a score of 46 on the Individualism dimension which means it can be considered to be a Collectivist society. It means loyalty towards the group is paramount. Moroccans tend to regulate their emotions in accordance with social norms, in order to “preserve interpersonal harmony, and prevent one from losing face or honor in the eyes of the group” (Novin et al., 2012, p. 578).

Hofstede et al. (2010) defined the cultural dimension Indulgence as “a tendency to allow relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun” in contrast with its opposite pole, Restraint which is “a conviction that such gratification needs to be curbed and regulated by strict social norms” (p. 281). Morocco is a restrained society (a score of 25 on this dimension). Thus, Moroccans tend to disapprove of indulgence and have a preference for low-arousal emotions, especially in formal contexts such as the classroom.

2.7 Chinese Cultural Context

China has developed a collectivist cultural ideology in the course of its historical development. Hofstede’s Country Comparison Tool indicates that China has a score of 20 on the Individualism dimension which means it can be considered to be a highly collectivist society. Individuals tend to act in the interest of the group rather than their own individual interest. China is also a restrained society (score of 24 on the dimension of Indulgence). Thus, Chinese tend to control the gratification of their desires. They also tend to be restrained in the display of personal emotions, either positive or negative, in order not to be too prominent in the group or seen as a show-off at the expense of others’ feelings or the balance between self and collective interest (Soto et al., 2011). This has given rise to a public social mentality that values low-arousal emotions (Lim, 2016). Harmony and balance in one’s emotional state is a tenet in Confucianism. Having this harmony inside, with others and with nature is linked with happiness (Li, 2020). Similarly, Taoism holds that it is important to keep harmony and balance inside and with the surroundings (Lu & Gilmour, 2004). In brief, Chinese culture and philosophy favour the internal emotional experience of peacefulness and harmony over physically gratifying experiences.

To sum up, according to Hofstede et al. (2010) Chinese are slightly more collectivist than Moroccans but equally restrained.

3 Research Questions

This study aims to compare the effects of FLPOM and FLE -and the relationships between them- on the performance of Chinese and Moroccan EFL learners, with the specific aim of examining to what extent FLPOM affects the performance of Moroccan learners. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to study FLPOM outside China and to compare the effect of cultural dimensions on FL learner emotions.

We will address the following research questions:

-

1.

Do participants report higher levels of FLPOM than FLE in their EFL classes?

-

2.

Do Chinese and Moroccan EFL learners report similar levels of FLE and FLPOM?

-

3.

Do Chinese and Moroccan EFL learners report similar levels of FLE Personal, FLE Teacher and FLE Social?

-

4.

What are the relationships between FLE, FLPOM and language performance for Chinese and Moroccan EFL learners?

-

5.

Is FLPOM more strongly associated with FL performance than FLE in the Moroccan EFL context?

4 Method

4.1 The Moroccan Sample

4.1.1 Participants

Participants were 502 Moroccan EFL learners from various public and private schools in different parts of the country. They were relatively young (M = 22.4 years, SD = 7), ranging from 14 to 60 years old. The sample consisted of 269 women (54.1%), 228 men (45.9%) with 5 participants who preferred not to disclose their gender. In terms of English proficiency 85 identified themselves as beginners (17%), 147 as lower intermediate (29%), 175 as upper intermediate (34.8%) and 95 as advanced learners (18.9%). The sample comprised 83 bilinguals, 258 trilinguals, 134 quadrilinguals, 19 pentalinguals and 8 participants who reported knowing six or more languages. In addition to English, they reported knowledge of Arabic (n = 462), French (n = 415), Amazigh (n = 146), Spanish (n = 39), Turkish (n = 14), and German (n = 12). Average self-reported English test results was 75.6% (SD = 16.2), suggesting that these were “good” students.

4.1.2 The Moroccan EFL Context

Moroccan students are required to take English, Spanish, French or German as a foreign language at public secondary schools, depending on the region in Morocco. English is about to take over French as the first foreign language (https://www.newarab.com/news/english-become-moroccos-first-foreign-language-ministry#). French had been imposed during the colonial period (1912–1956) and remained central in education. EFL learners start learning English in public middle school at around the age of 12 (2 h a week) and take it further in high school (3, 4 or 5 h a week depending on the stream). Their EFL trajectory involves a high-stakes written exam in their final year (Baccalaureate), which accounts for 50% of their achievement grade in English. The other 50% is accounted for by performance in term tests during the last two years. English learning is popular in Morocco as the language is perceived to be prestigious (Dressman, 2019). The EFL curriculum at public schools adopts a standards-based approach which focuses on developing learners’ communicative competence, while other curricula are followed at private schools.

4.1.3 Instruments

An online questionnaire was presented in English and Arabic to ensure full understanding of the items by participants. The second author translated the questionnaire from English into Arabic and checked the translation with a colleague English/Arabic teacher. The two discussed and resolved minor differences on how some items should be translated. The first section focused on sociobiographical and linguistic background and included one item about the latest English major test result. The second section contained the FLE and FLPOM scales.

Short-Form Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (α = 0.92)

This 9-item scale was developed by Botes et al. (2021). In addition to an overall FLE scores, it provides values for three subdimensions: Personal Enjoyment (“I am proud of my accomplishments”), Social Enjoyment (“We laugh a lot”), and Teacher Appreciation (“The teacher is encouraging”). Answers to the items were based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 2 = ‘disagree’, 3 = ‘undecided’, 4 = ‘agree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’), and all items were positively phrased.

Foreign Language Peace of Mind Scale (α = 0.94)

This 8-item scale was developed in Zhou et al. (2023a). Items included were “I feel peace and comfort in the English class” and “I am able to find inner peace and harmony when experiencing stress or pressure in English learning.” All items were positively phrased and based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 2 = ‘disagree’, 3 = ‘undecided’, 4 = ‘agree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’).

4.1.4 Data Collection

Ethical Approval for this study was obtained at the first and second authors’ research institution. The questionnaire targeted Moroccan EFL learners regardless of age (from 14 upwards), institution, place and the level of FL mastery, using a snowball sampling strategy. Participants’ individual consent was obtained at the start of the survey, and no names of students, teachers or schools were collected. Their anonymity, rights, and the confidentiality of their information were explained and guaranteed. A call for participation was placed on professional networks and social media (LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram). The questionnaire was posted online and remained accessible throughout June 2022. Participants were encouraged to share the call for participation with their peers.

4.2 The Chinese Sample

4.2.1 Participants

Participants were 400 Chinese senior high school EFL students —the same sample that was used for study 2 in Zhou et al. (2023a). They came from one of four senior high schools in Beijing (North China), Jiangsu (South China), and Anhui (Middle China). The participants (138 men, 262 women) had an average age of 16.5, ranging from 15 to 21. They had Mandarin Chinese as a first language. English was their only FL. Asked to rate their English proficiency, 21 participants identified as beginners (5.2%), 117 as lower intermediate (29.2%), 240 as upper intermediate (60%) and 22 as advanced learners (5.5%). They also reported the result of their most recent English test, with a mean score of 77.03 (SD = 12.25), suggesting that they were good English learners.

4.2.2 The Chinese EFL Context

Chinese students start learning English in early childhood. At the elementary level, students begin receiving formal English language education and taking English tests or assessments. In general, English is the only second language available to Chinese students at the primary and secondary levels. For secondary students, English is very important because it is a major subject and is given a great weighting in the national college entrance examination or Gaokao, a high-stakes examination on which students’ future depends. Therefore, Chinese students are required to invest a lot of time and energy in English learning, accompanied by English tests conducted on a weekly or monthly basis. A strong examination-oriented culture has been identified in the Chinese EFL context (Jiang & Dewaele, 2019) which affects learner emotions. In addition, EFL teaching and learning in China, especially at the primary and secondary levels, predominantly focuses on students’ reading and writing competence rather than speaking competence (Wang, 2014).

4.2.3 Instruments

Foreign Language Peace of Mind Scale

FLPOM was measured with the newly developed 8-item scale with 5-point Likert scales (Zhou et al., 2023a). It had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.94).

The Chinese Foreign Language Enjoyment Scale (CFLES) (α = 0.90)

FLE was measured with the validated Chinese version (Li et al., 2018) of the original FLE scale (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). It consists of 11 items with 5-point Likert scales. It measures 3 dimensions (FLE-Private, FLE-Teacher and FLE-AtmosphereFootnote 3). It had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.90).

4.2.4 Data Collection

An anonymous online survey was administered in the above-mentioned four senior high schools through convenience sampling. A composite questionnaire was used to collect data on participants’ demographics, FLE, and FLPOM. The online survey was distributed via WeChat, a popular Chinese social media. Researchers contacted numerous high school teachers in China and asked them to administer the survey among their students as a part of their coursework. Informed consent was obtained from both teachers and participants at the start of the survey.

4.3 Data Analysis

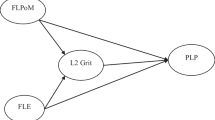

The Chinese and Moroccan databases were merged and analysed using SPSS software (29th version). The calculation of the Q-Q (quantile-quantile) showed plots for FLE, FLPOM and language performance to follow a normal distribution reasonably well (available from the authors on request). This allowed the use of parametric statistics. After running descriptive and normality tests, other inferential statistics were conducted. First, independent t-tests were run to compare FLE (including its three subdimensions) and FLPOM in both groups. Second, a Pearson correlation analysis was run to examine the relationships among FLE, FLPOM and language performance within the Chinese and Moroccan EFL groups. Finally, three rounds of regression analysis were run to examine the associations between FLE, FLPOM and the FL performance of Moroccan EFL learners, and the results were compared with the published findings of the Chinese sample (Zhou et al., 2023a).

5 Results

5.1 FLE and FLPOM in Chinese and Moroccan EFL Learners

Paired t-tests within the groups of Chinese and Moroccan EFL learners showed that both groups scored significantly higher on FLE than on FLPOM (t(399) = 9.36, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.55 and (t(501) = 4.29, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.63 respectively) (see Fig. 1).

An independent t-test on the complete database revealed that Moroccan EFL learners scored significantly higher on FLPOM than their Chinese peers (see Table 1). Similarly, Moroccan participants scored significantly higher on FLE than the Chinese participants (see Table 1).

A closer look at the three dimensions of FLE revealed striking differences between both groups. Moroccans scored significantly higher on FLE Personal than the Chinese (a large effect size) (see Table 1). In contrast, the Chinese scored significantly higher on FLE Teacher and on FLE Social than the Moroccans (a small effect size) (see Table 1).

5.2 Relationships Between FLE, FLPOM and Performance in Chinese and Moroccan EFL Learners

Pearson correlation analyses revealed that FLE and FLPOM were significantly positively related both in the Chinese and in the Moroccan samples: (r(400) = 0.70, p < .001); and (r(502) = 0.67, p < .001) respectively. The two variables shared 50.1% and 46.1% of the variance in the two groups respectively, which represent large effect sizes (Plonsky & Oswald, 2014) FLE and FLPOM were significantly positively correlated with EFL performance in both groups (see Table 2).

5.3 The Associations Between FLPOM, FLE and Performance of Moroccan EFL Learners

Three rounds of regression analysis were conducted, and three models were produced –with FLE, FLPOM, and FLE + FLPOM as predictors, respectively.

In Model 1, FLE was entered as the independent variable. FLE had a significant association with language performance (β = 0.24, p < .001), explaining 5.9% of the total variance of Moroccan learners’ FL performance.

In Model 2, with FLPOM as the independent variable, FLPOM had a significant association with Moroccan learners’ language performance (β = 0.26, p < .001), explaining 6.9% of the total variance of FL performance.

In Model 3, both FLE and FLPOM were used simultaneously as independent variables. FLE had a significant association with FL performance (β = 0.12, p = .041); as was the case for FLPOM (β = 0.18, p < .002). Together they accounted for 7.7% of the total variance of FL performance.

The Models 1 and 2 suggest that both FLE and FLPOM had small independent effects on FL performance (Cohen, 1988), with FLPOM explaining an extra 1% of variance. Model 3 confirmed this pattern, showing that FLPOM and FLE jointly explained an additional 0.8% of variance (still a small effect size). Considering the standardized beta coefficients in Model 3, it seems the association between FLPOM and FL performance is slightly stronger than between FLE and FL performance.

5.4 Reminder of the Key Findings in Zhou et al. (2023a)

Given the fact that the analyses of the effects of FLPOM and FLE on FL performance of Chinese EFL were already carried out in Zhou et al. (2023a), we will only offer a quick overview of the main statistical findings here. FLPOM and FLE were significantly positively correlated (r = .708, p < .0001) (p. 14). Stepwise regression analyses resulted in three Models. In Model 1, only FLE was introduced as the independent variable and it was shown to have a significant positive effect on self-perceived proficiency (β = 0.29, p < .001), explaining 8.2% of variance (p. 17). In Model 2, FLPOM was the only independent variable and it also emerged as a positive predictor of self-perceived proficiency (β = 0.35, p < .001), explaining 12.5% of the variance (p. 17). In Model 3, FLE and FLPOM were entered simultaneously. The effect of FLE faded (β = 0.07, p = .285) whereas the effect of FLPOM remained significant (β = 0.30, p < .001) (p. 17). Model 3 explained 12.8% of variance which is 4.6% higher than Model 1 and only 0.3% higher than Model 2 (p. 17). This suggests that FLPOM was a stronger predictor of self-perceived proficiency than FLE (p. 17).

6 Discussion

The first research question focussed on values for FLE and FLPOM in both groups. Values for FLE were found to be significantly higher than those for FLPOM in both the Chinese and Moroccan groups. This suggests that despite a cultural inclination towards Restraint and low-arousal emotions in both cultures, our participants actually reported higher levels of FLE than Peace of Mind in their EFL classes. It is possible that EFL classes are unique cultural spaces where learners come into contact with new concepts (Wisniewski et al., 2019) which may encourage them to expand their range of cultural values and emotions. Further cross-cultural research on FL learner emotions is needed to establish to what extent cultural inclinations shape how learners feel in the FL classroom.

Independent t-tests on the whole database were used to answer the second research question. They showed that Moroccan EFL learners’ scores on FLPOM and FLE were significantly higher than those of their Chinese peers. The difference cannot be attributed to Indulgence versus Restraint as both groups have a very similar score on this cultural dimension (Hofstede et al., 2010). The fact that Morocco is a slightly less collectivist society than China might explain the higher scores on medium-to-high arousal FLE but can certainly not account for the higher scores on the low-arousal FLPOM. There is no obvious explanation for this finding. It is possible that the Moroccan educational context is slightly less stressful and competitive than the Chinese context. It thus seems that FLPOM might be a Chinese culture-specific emotion but that it might very well be experienced by EFL learners in other collectivist cultures, and possibly even in more individualistic and indulgent cultures, where concepts like ‘mindfulness’ are increasingly popular and introduced in education systems (Morgan & Katz, 2021).

The third research question focused on differences between the two groups for the three subdimensions of FLE. The biggest difference was found for FLE Personal where the Moroccans scored much higher than the Chinese (big effect size). In contrast, the Chinese scored significantly higher on the dimensions FLE Teacher and FLE Social than the Moroccans (small effect size). This indicates that the Moroccan group most appreciated the aspect of FLE that taps into intellectual stimulation and is a strong predictor of the experience of flow in the FL classroom (Dewaele et al., 2023b). The Chinese cohort had a preference for the social aspects of enjoyment. The latter might be linked to the higher score on Collectivism (Hofstede et al., 2010) and the deeply rooted culture of reverence for teachers in China (Hu, 2002). What these findings suggest is that despite communalities between both groups (Collectivism and Restraint), there are also differences which could be linked to educational practices, as well as to historical Western influences in Morocco.

The next research question addressed the relationship between FLE, FLPOM and EFL performance within both groups. Strong positive correlations were found between FLE and FLPOM in the Chinese and Moroccan groups, suggesting that the two emotions tend to co-occur. This makes sense as FL classes may include moments of laughter and high arousal but may also include periods of silent work where a low-arousal positive emotion gives learners the serenity they need to avoid distractions and to perform well (Haskins, 2010; Zhou et al., 2023a). Botes et al. (2020a) argued that causality between positive emotions and performance is probably bi-directional. Increased proficiency boosts FLE (and FLPOM) and higher levels of FLE (and FLPOM) further strengthen the effort to learn the FL, boosting the ability to reach a state of flow (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2022; Dewaele et al., 2023b) and resulting in a positive feedback loop. The present findings are in line with the extensive literature on the relationship between positive emotions and all types of academic achievement (Botes et al., 2020b, 2022a; Li et al., 2020; Saito et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2023a).

The final research question focused on the association between FLPOM and FL performance in the Moroccan EFL context. The results revealed that FLPOM had a stronger positive association with FL performance than FLE. This result mirrors the previous findings on the importance of the construct of Peace of Mind in educational contexts within collectivist cultures (Datu, 2017; Datu et al., 2018). It also reflected the finding in Zhou et al. (2023a) that FLPOM had a slightly stronger effect - after FLE was controlled for – than FLE. The authors speculated that a mid-to-high arousal positive emotion like FLE might be more effective in individualistic Western contexts while a low-arousal positive emotion like FLPOM might stimulate performance in more collectivist contexts. Our findings suggest that despite experiencing higher levels of FLE than FLPOM, it was the latter that provided the key to better performance among our participants. One possible explanation is that FLPOM has deeper cognitive and motivational consequences than FLE (Zhou et al., 2023b). The unexpected stronger effect of FLPOM compared to FLE among Moroccan learners might be linked to their higher (Personal) FLE: maybe they reached an enjoyment threshold by finding the perfect balance between challenge and skill (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014) that allowed them to boost (and maintain) their FLPOM to a higher level than their Chinese peers. FLPOM did explain a slightly higher amount of variance in the performance of the Chinese learners compared to the Moroccan learners.

7 Limitations and Implications

Some limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Firstly, inevitable self-selection bias means that the samples do not represent the general populations of EFL learners in Morocco and China. As Dörnyei and Dewaele (2023) pointed out, ‘good’ learners are more likely than ‘bad’ learners to spend time answering a questionnaire on their FL experiences, and this applies to the Moroccan context as well as the Chinese context. Crucially, both groups had similar profiles for English. Secondly, the choice of a cross-sectional design means that the present study can only offer a snapshot of complex and dynamic FL emotions (Dewaele et al., 2023a; Elahi Shirvan et al., 2021; Kruk et al., 2021, 2023). Thirdly, self-reported measures of performance may not be completely accurate but they are the next best thing when it is impossible to collect more precise measures (Zhang et al., 2020).

These findings have some pedagogical implications that could inform the curriculum and pedagogy. While both FLE and FLPOM have positive effects in various educational contexts, teachers need to be aware that depending on the context the low-arousal FLPOM may have a slightly stronger effect than the medium-to-high arousal FLE. It also means that teaching pedagogies developed in WEIRD contexts, like the communicative language approach which may generate medium-to-high arousal emotions, may be sub-optimal in different cultural contexts (Littlewood, 2007). It is thus crucial for teachers to adapt teaching pedagogies to their learners’ context (Li et al., 2020), and to attune to their emotional preferences. For example, some students prefer learner-centred activities such as games and role-play that can trigger high arousal emotions, whereas others are more comfortable with teacher-centred styles that avoid high arousal. Finally, since positive emotions affect FL performance, it is crucial that teacher training programmes include this important finding in their curriculum (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2016).

8 Conclusion

The title of the present paper refers to an apparent contradiction: how could values for FLPOM -with its deep roots in traditional Chinese culture - be lower and and yet have a slightly stronger effect on the performance of Chinese EFL learners compared to Moroccan EFL learners who live more than 9600 km away? There is no clear answer because despite communalities (Restraint and -to a slightly lesser degree- Collectivism), Chinese and Moroccan cultures also have differences linked to their unique histories and educational practices. FLPOM might resonate more strongly with Moroccan EFL learners because their educational context is (marginally) less stressful and competitive. A closer look at the FLE dimensions revealed that the Moroccan learners valued the dimension FLE Personal much more than their Chinese peers, which could be the general prerequisite for increased FLPOM.

The finding that both groups reported higher levels of the medium-to-high arousal FLE and yet that the low-arousal FLPOM had a stronger association with their English performance better underlines the need to avoid simplistic generalisations about FL learner emotions. It suggests that variation exists both between and within collectivist cultures. Learners experience a wide range of interacting positive and negative emotions simultaneously, linked to their personality, the teaching context and their cultural roots, and the optimal alignment of a wide range of independent variables will lead to good performance. Further research is needed to investigate what specific factors in the Moroccan EFL context are responsible for the higher scores on FLPOM and its association with performance compared to the Chinese EFL context. It is also imperative to investigate the association between FLPOM and FL performance of learners of various target languages in a wide variety of WEIRD and non-WEIRD cultures.

Notes

China was found to score higher on Power Distance (80 versus 70), Masculinity (66 versus 55), Long Term Orientation (87 versus 14). Morocco scored higher on Uncertainty Avoidance (68 versus 30).

References

Andringa, S., & Godfroid, A. (2020). Sampling bias and the problem of generalizability in applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 40, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190520000033

Botes, E., Dewaele, J. M., & Greiff, S. (2020a). The power to improve: Effects of multilingualism and perceived proficiency on enjoyment and anxiety in Foreign Language Learning. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(2), 279–306. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2020-0003

Botes, E., Dewaele, J., & Greiff, S. (2020b). The foreign language classroom anxiety scale and academic achievement: An overview of the prevailing literature and a meta-analysis. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 2, 26–56.

Botes, E., Dewaele, J., & Greiff, S. (2021). The development and validation of the short form of the foreign language enjoyment scale. The Modern Language Journal, 105(4), 858–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12741

Botes, E., Dewaele, J. M., & Greiff, S. (2022a). Taking stock: A meta-analysis of the effects of foreign language enjoyment. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 12(2), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.2.3

Botes, E., Dewaele, J., & Greiff, S. (2022b). By the old gods and the new: The Effect of the congruence and incongruence of Foreign Language Classroom anxiety and enjoyment on self-perceived proficiency. The Modern Language Journal, 106(4), 784–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12807

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Datu, J. A. D. (2017). Peace of mind, academic motivation, and academic achievement in Filipino High School Students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20, E22. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2017.19

Datu, J. A. D., Valdez, J. P. M., & King, R. B. (2018). Exploring the association between peace of mind and academic engagement: Cross-sectional and cross-lagged panel studies in the Philippine context. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(7), 1903–1916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9902-x

Dewaele, J. M., Chen, X., Padilla, A. M., & Lake, J. (2019). The flowering of positive psychology in foreign language teaching and acquisition research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02128

Dewaele, J. M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 237–274. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewaele, J. M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2016). Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: The right and left feet of the language learner. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive Psychology in SLA (pp. 215–236). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783095360-010

Dewaele, J. M. (2022). Enjoyment. In S. Li, P. Hiver, & M. Papi (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Individual differences (pp. 190–206). Routledge.

Dewaele, J. M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2022). You can’t start a Fire without a spark. Enjoyment and the emergence of Flow in Foreign Language classrooms. Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0123

Dewaele, J. M., & Meftah, R. (2023). The trajectory of English foreign learners’ emotions and motivation from the start to the end of their learning journey. Journal of the European Second Language Association, 7(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.94

Dewaele, J.-M., & Meftah, R. (2024). How motivation and enjoyment spread their wings during English Foreign Language learning: A pseudo-longitudinal investigation into Moroccan learners. Learning and Motivation, 85. https://doi.org/10.1016//j.lmot.2024.101962

Dewaele, J. M., Botes, E., & Meftah, R. (2023a). A three-body problem: The effects of Foreign Language anxiety, enjoyment, and Boredom on Academic Achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 43, 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190523000016

Dewaele, J. M., MacIntyre, P. D., Albakistani, A., & Kamal Ahmed, I. (2023b). Emotional, attitudinal and sociobiographical sources of flow in online and in-person EFL classrooms. Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amad071

Dörnyei, Z., & Dewaele, J. M. (2023). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003331926

Dressman, M. (2019). Informal English Learning Among Moroccan Youth. In M. Dressman & R. W. Sadler (Eds.), The Handbook of Informal Language Learning (pp. 303–318). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119472384.ch20

Elahi Shirvan, M., Taherian, T., & Yazdanmehr, E. (2021). Foreign language enjoyment: A longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis–curve of factors model. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–19, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1874392

Ennaji, M. (2005). Multilingualism, cultural identity, and education in Morocco. Springer.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Haskins, C. (2010). Integrating silence practices into the classroom: The value of quiet. Encounter: Education for Meaning and Social Justice, 23(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.15730/forum.2016.58.3.399

Hofstede, G. H., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Hu, G. (2002). Potential cultural resistance to pedagogical imports: The case of communicative language teaching in China. Language Culture and Curriculum, 15(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310208666636

Jiang, Y., & Dewaele, J. M. (2019). How unique is the foreign language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? System, 82, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.02.017

Kruk, M., Elahi Shirvan, M., Pawlak, M., Taherian, T., & Yazdanmehr, E. (2021). A longitudinal study of the subdomains of boredom in practical English language classes in an online setting: A factor of curves latent growth modeling. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–15, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.2006404

Kruk, M., Pawlak, M., Taherian, T., Yüce, E., Elahi Shirvan, M., & Barabadi, E. (2023). When time matters: Mechanisms of change in a mediational model of foreign language playfulness and L2 learners’ emotions using latent change score mediation model. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 13(1), 39–69. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.37174

Lee, Y. C., Lin, Y. C., Huang, C. L., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). The construct and measurement of peace of Mind. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902

Li, C. (2020). Bring back Harmony in philosophical discourse: A confucian perspective. Journal of Dharma Studies, 2(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42240-019-00047-w

Li, C., Dewaele, J. M., & Jiang, G. (2020). The complex relationship between classroom emotions and EFL achievement in China. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(3), 485–510. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0043012-9343-5

Li, C., & Han, Y. (2022). The predictive effects of foreign language anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom on learning outcomes in online English classrooms. Modern Foreign Languages(《现代外语》), 45(2), 207–219.

Li, C., Jiang, G., & Dewaele, J. M. (2018). Understanding Chinese high school students’ Foreign Language enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the Foreign Language enjoyment scale. System, 76, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.06.004

Li, C., & Wei, L. (2023). Anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom in language learning amongst junior secondary students in rural China: How do they contribute to L2 achievement? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263122000031

Lim, N. (2016). Cultural differences in emotion: Differences in emotional arousal level between the East and the West. Integrative Medicine Research, 5(2), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2016.03.004

Littlewood, W. (2007). Communicative and task-based language teaching in east Asian classrooms. Language Teaching, 40(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444807004363

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented swb. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8789-5

MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: The positive-broadening power of the imagination. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(2), 193. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

Macintyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2019). Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: Theory, practice, and Research. The Modern Language Journal, 103(1), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12544

Morgan, W. J., & Katz, J. (2021). Mindfulness meditation and foreign language classroom anxiety: Findings from a randomized control trial. Foreign Language Annals, 54(2), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12525

Njoku, R. C. (2006). Culture and customs of Morocco. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Novin, S., Banerjee, R., & Rieffe, C. (2012). Bicultural adolescents’ anger regulation: In between two cultures? Cognition & Emotion, 26(4), 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.592084

Oumlil, A. B., & Balloun, J. L. (2017). Cultural variations and ethical business decision making: A study of individualistic and collective cultures. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 32(7), 889–900. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-08-2016-0194

Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is Big? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 Research: Effect sizes in L2 Research. Language Learning, 64(4), 878–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079

Saito, K., Dewaele, J. M., Abe, M., & In’nami, Y. (2018). Motivation, emotion, learning experience, and second language comprehensibility development in classroom settings: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study: Motivation and emotion in L2 Speech Learning. Language Learning, 68(3), 709–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12297

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Soto, J. A., Perez, C. R., Kim, Y. H., Lee, E. A., & Minnick, M. R. (2011). Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion, 11(6), 1450–1455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023340

Wang, Z. (2014). Developing accuracy and fluency in Spoken English of Chinese EFL Learners. English Language Teaching, 7(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n2p110

Wisniewski, D., Deutschländer, R., & Haynes, J. D. (2019). Free will beliefs are better predicted by dualism than determinism beliefs across different cultures. PLoS ONE, 14(9), e0221617. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221617

Yu, S., Zhang, F., Nunes, L. D., Deng, Y., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2020). Basic psychological needs as a predictor of positive affects: A look at peace of mind and vitality in Chinese and American college students. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1627398

Zhang, H., Dai, Y., & Wang, Y. (2020). Motivation and second Foreign Language proficiency: The mediating role of Foreign Language Enjoyment. Sustainability, 12(4), 1302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041302

Zhou, L., Dewaele, J. M., Lochtman, K., & Xi, Y. (2023a). Foreign language peace of mind: A positive emotion drawn from the Chinese EFL learning context. Applied Linguistics Review, 14(5), 1385–1410. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0080

Zhou, L., Lochtman, K., & Xi, Y. (2023b). The mechanism for the positive effect of foreign language peace of mind in the Chinese EFL context: A moderated mediation model based on learners’ individual resources. Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0105

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the Chinese and Moroccan students and teachers who participated and contributed to data collection for this study. We gratefully acknowledge the help of all these people, without whom the completion of this research would not have been possible.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval was granted by the first and second author’s research institution.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dewaele, JM., Meftah, R. & Zhou, L. Why do Moroccan English Foreign Language learners experience more Peace of Mind (外语平和心态) than Chinese EFL learners and how does it affect their performance?. Int J Appl Posit Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00141-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00141-2