Abstract

This study examines the pace and pattern of employment in India during the last four decades using the Employment-Unemployment Survey (EUS) (1983 to 2011–12) and Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) (2017–18 to 2020–21). The estimates reflect that, notwithstanding the impressive economic growth, aided by demographic dividend, the economy has witnessed a low sustained employment generation. The present analysis reflects a notable increase in both output growth and employment between the years 1983 and 2004-05. However, subsequent to this period, there exists a distinct phase of economic development characterised by a lack of job creation from 2004–05 to 2017-18 and a rebound thereafter. The concerning divergence between Gross Value Added (GVA) growth and employment growth is reflected in the continued dominance of agriculture in terms of employment share even when its GVA share is dismal. Besides, the low employment elasticities of non-farm sectors including industry and services indicate the inability of the non-farm sector to absorb additional labour force and hence sluggish employment opportunities. The slow rate of employment growth during the period of high economic growth failed to bring down overall unemployment. Consequentially, the findings serve as a rebuttal to the claim of ‘slow’ structural transformation. Not only that the labour market is characterising by significant gender disparity, but there is also a growing level of unemployment for the highly educated youth than the less educated. Apparently, economic growth rather than creating more jobs has resulted in net labour displacement as can be seen from the disaggregated analysis of Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), Work Force Participation Rate (WFPR), and unemployment rate. The discourse of falling and lower employment elasticities and strong GVA growth painting a discordant picture of the economy calls for an urgent policy redressal in expanding the human capacity to participate in the new economic and social opportunities.

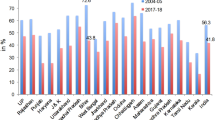

Source: Computed from the unit level datasets of different NSSO and PLFS

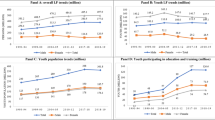

Source: Computed from the unit level datasets of different NSSO and PLFS

Source: Computed from the unit level datasets of different NSSO and PLFS

Source: Computed from the unit-level datasets of different NSSO EUS and PLFS

Source: Computed from the unit-level datasets of different NSSO EUS, PLFS, and from MOSPI

Source: Computed from the unit level datasets of different NSSO EUS, PLFS rounds

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The percentage of unemployed people in the entire labour force is known as the unemployment rate (UR).

Please see Report No. 554, the 68th NSSO Employment and Unemployment Survey, for more information on how population projections were calculated. “The census adjustment has been done on the basis of census and NSSO employment data sets. First the weighted NSSO population figure is estimated from the concerned NSSO employment and unemployment rounds both for rural-urban and male and female differently after that the given figures are divided by the concerned census population figures. After getting the ratios, they are multiplied with the multiplier figures to get the census adjusted weights.”

“In this approach the status of activity on which a person spent relatively longer time of the preceding 365 days from the date of survey is considered as the principal usual activity of the person (MOSPI, 2012). Accordingly, a person is considered working or employed, if the person was engaged for a relatively longer time during the past year in one or more work related activities”. Details can be found in the NSSO employment and unemployment reports that are issued afterwards. The employment and unemployment numbers from the NSSO are directly used in this approach.”

Employment elasticity of output measures the responsiveness of employment with responsiveness change in output.

In the case \(Ee\) <o, employment falls as the economy grows. Having \(Ee\) =1, indicates that employment is growing at the same rate as the economy, when \(Ee\) = zero, employment does not grow at all even during an economic boom.

References

NITI Aayog. 2022. India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy: Perspectives and Recommendations on the Future of Work. Retrieved from https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-06/25th_June_Final_Report_27062022.pdf

Abraham, V. 2009. Employment Growth in Rural India: Distress-Driven? Economic and Political Weekly 18: 97–104.

Abubakar, J., and I. Nurudeen. 2019. Economic Growth in India, is it a Jobless Growth? An Empirical Examination Using Okun’s Law. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 62: 307–317.

Afridi, F., A. Mukhopadhyay, and S. Sahoo. 2016. Female Labor Force Participation and Child Education in India: Evidence from the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme. IZA Journal of Labor & Development 5 (1): 7.

Arora, P. 2012. The Rigid Employment Protection Legislations in India and its Impact on the Economy: Is Flexicurity a Viable Solution. NALSAR Stud. l. Rev. 7: 40.

Basole, A. 2022. Structural Transformation and Employment Generation in India: Past Performance and the Way Forward. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65 (2): 295–320.

Basole, A., and A. Narayan. 2020. Long-run Performance of the Organised Manufacturing Sector in India: An Analysis of Sub-Periods and Industry-Level Trends. Economic and Political Weekly 55 (10): 35–44.

Basu, Deepankar and Debarashi Das. 2016. Employment Elasticity in India and the US, 1977–2011

Bertrand, M. 2018. Coase Lecture: The Glass Ceiling. Economica 85 (338): 205–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12264.

Bhandari, L., & Dubey, A. 2019. Emerging Employment Patterns of 21st Century India. Indicus Foundation White Paper, 11.

Binswanger-Mkhize, H.P. 2013. The Stunted Structural Transformation of the Indian Economy. Economic and Political Weekly 48 (26–27): 5–13.

Blau, F.D., and L.M. Kahn. 2017. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature 55 (3): 789–865. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995.

Breitkreuz, R., C.-J. Stanton, N. Brady, J. Pattison-Williams, E. King, C. Mishra, and B. Swallow. 2017. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: A Policy Solution to Rural Poverty in India? Development Policy Review 35 (3): 397–417.

Cai, F., and M. Wang. 2008. A Counterfactual of Unlimited Surplus Labour in Rural China. China World Economic 16: 51–65.

Cantore, Nicola, Michele Clara, Alejandro Lavopa, and Camelia Soare. 2017. Manufacturing as an Engine of Growth: Which is the Best Fuel?”. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 42: 56–66.

Cervantes-Godoy, D. and J. Dewbre. 2010. Economic Importance of Agriculture for Poverty Reduction. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Working Papers, No. 23. OECD Publishing https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmmv9s20944-en.

Chadha, G.K., and P.P. Sahu. 2002. Post-Reform Setbacks on Rural Employment: Issues that Need Further Scrutiny. Economic and Political Weekly 37 (21): 1998–2026.

Chandrasekhar, C.P., Jayati Ghosh, and Anamitra Roychowdhury. 2006. The Demographic Dividend and Young India’s Economic Future. Economic and Political Weekly 2006: 5055–5064.

Cortes, P., and J. Pan. 2018. Occupation and Gender. In The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, ed. S.L. Averett, L.M. Argys, and S.D. Hoffman, 425–452. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.12.

Das, M., and P. N’Diaye. 2013. Chronicle of a Decline Foretold: Has China Reached the Lewis Turning Point? IMF Working Paper 13/26. Washington D.C.

Ding, YingYing, Zheng Li, Xiaojun Ge, and Hu. Yu. 2020. Empirical Analysis of the Synergy of the Three Sectors’ Development and Labor Employment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 160: 120223.

Dubey, A., W. Olsen, and K. Sen. 2017. The Decline in the Labour Force Participation of Rural Women in India: Taking a Long-Run View. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 60 (4): 589–612.

Estupinan, X., S. Gupta, M. Sharma, and B. Birla. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Labour Supply, Wages and Gross Value Added in India. The Indian Economic Journal 68 (4): 572–592.

Everlance 2018. Self-Employment Statistics in the US.Retrieved from https://www.everlance.com/blog/self-employment-statistics/ March 28, 2020.

Fallick, Bruce, and Jonathan F. Pingle. 2007. A Cohort-based Model of Labor Force Participation. Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/PUBS/FEDS/2007/200709/200709pap.pdf

Ghose, Ajit K., and Abhishek Kumar. 2021. India’s Deepening Employment Crisis in the Time of Rapid Economic Growth. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 64 (2): 247–279.

Ghose, Ajit K. 2013. The Enigma of Women in the Labourforce, Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 56 (4): .

Ghose, Jayati 2013. The Strange Case of the Jobs that did not Appear: Structural Change, Employment and Social Patterns in India, Presidential Address, 55th Annual Conference, The Indian Society of Labour Economics, held during 16–18 December at CESP, JNU, New Delhi.

Gomis, Roger, Steven Kapsos, and Ste Kuhn. 2020. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Geneva: ILO.

Goswami, Diti, and Sandeep Kumar Kujur. 2023. Risk-Reducing Strategies and Labour Vulnerability during the pandemic in India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 93: 103763.

Himanshu. 2011. Employment Trends in India: A Re-examination. Economic and Political Weekly 46 (37): 43–59.

Hirway, Indira. 2012. Missing Labourforce: An Explanation. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (37): 43–59.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2019a. A quantum leap for gender equality: For a better future of work for all (Geneva).

ILO 2021. Situation Analysis on the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Enterprises and Workers in the Formal and Informal Economy in India. ILO DWT for South Asia and Country Office for India. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_798079.pdf

Imbert, C., and J. Papp. 2015. Labor Market Effects of Social Programs: Evidence from India’s Employment Guarantee. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7 (2): 233–263.

Kaldor, N. 1966. Causes of the Slow Rate of Economic Growth of the United Kingdom. Cambridge University Press.

Kaldor, N. 1967. Strategic Factors in Economic Development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kannan, K.P., and G. Raveendran. 2019. From Jobless to Job-Loss Growth: Gainers and Losers During 2012–2018. Economic and Political Weekly 54 (44): 38–44.

Kannan, K.P., and G. Ravindran. 2012. Counting and Profiling the Missing Labour Force. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (6): 77–80.

Klasen, S., and J. Pieters. 2015. What Explains the Stagnation of Female Labor Force Participation in Urban India? The World Bank Economic Review 29 (3): 449–478.

Kumar, M.S., and P.P. Sahu. 2013. Employment Growth, Education and Skills in India: Emerging Perspectives. Indian Journal of Labour Economics 56 (1): 95–122.

Kumar, A., N. Deka, S. Bathla, S. Saroj, and S.K. Srivastava. 2020. Rural Non-Farm Employment in Eastern India: Implications for Economic Well-Being. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63: 657–676.

Majid, N. 2021. Young Persons Not in Employment and Education (NEET) in India: 2000–2019. International Labor Organization Research Brief, March (March 2020).

Mehrotra, S., and J.K. Parida. 2021. Stalled Structural Change Brings an Employment Crisis in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 64 (2): 281–308.

Mehrotra, S., and S. Sinha. 2017. Explaining Falling Female Employment During a High Growth Period. Economic & Political Weekly 52 (39): 54–62.

Mehrotra, Santosh, Ankita Gandhi, Bimal Kishore Sahoo, and Partha Saha. 2012. Creating Employment in the Twelfth Five-Year Plan. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (19): 63–73.

Mehrotra, Santosh, Ankita Gandhi, Partha Saha, and Bimal Kishore Sahoo. 2013. Turnaround in India’s Employment Story: Silver Lining amidst Joblessness and Informalisation? Economic and Political Weekly 48 (35): 87–96.

Mehrotra, S. and J. Parida, 2019. India’s Employment Crisis: Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-agricultural Job Growth, Azim Premji University.

Mehta, Balwant Singh. 2018. India’s Pace of Moving Towards Lewis Turning Point. Amity Journal of Economics 3 (1): 15–34.

Mitra and Srivastava 2021. Reliability of PLFS 2019–20 data, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol LVI, No 39

Mitra, Arup, and Jitender Singh. 2019. Rising Unemployment in India: A Statewise Analysis from 1993–94 to 2017–18. Economic and Political Weekly 54 (50): 12–16.

Mitra, A. 2013. Insights into Inclusive Growth, Employment and Wellbeing in India, Springer New Delhi.

Mody, Ashoka. 2006. Inclusive Growth: K N Raj on Economic Development, Orient Longman, Hyderabad, for Sameeksha Trust.

Nagaraj, R. 2008. India’s Recent Economic Growth: A Closer Look. Economic and Political Weekly 43 (15): 55–61.

Naidu, S. 2015. Missing Women Workers: Explaining the Decline in Women’s Labor-Force Participation in India. Dollars & Sense 320: 30.

Naidu, S.C. 2016. Domestic Labour and Female Labour Force Participation: Adding a Piece to the Puzzle. Economic and Political Weekly 51 (44–45): 101–108.

Nath, P. and A. Basole 2021. Did Employment Rise or Fall in India Between 2011 to 2017? estimating absolute changes in the workforce, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol LVI No 34.

Neetha, N. 2014. Crisis in Female Employment. Economic and Political Weekly 49 (47): 50–59.

Neff, Daniel, Kunal Sen, and Veronika Kling. 2012. The Puzzling Decline in Rural Women’s Labourforce Participation in India: A Reexamination. Indian Journal of Labour Economics 55 (3): 407–429.

Padhi, B., and V. Motkuri. 2021. Labour Force and Employment Growth in India. Economic & Political Weekly 56 (47): 59.

Padhi, B., and P.P. Sahu. 2016. Jobless Growth and Challenges of Skill in India: The Emerging Regional Pattern, Paper Presented in the 58th Annual Conference, The Indian Society of Labour Economics, held during 24–26 November 2016 at IIT Guwahati, Assam.

Padhi, B., and H. Sharma. 2023. Changing Contours of Growth and Employment in the Indian Labour Market: A Sectoral Decomposition Approach. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2023.08.004.

Padhi, B., U.S. Mishra, and U. Pattanayak. 2019. Gender Based Wage Discrimination in Indian Urban Labour Market: An Assessment. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 62 (3): 361–388.

Padhi, B. and Triveni. T. 2021. Employment and Informality in the Indian Labour Market: Emerging Trends, Labour & Development, Vol. 28, No.1

Papola, T. S. and Sahu 2012. Growth and Structure of Employment: Long-Term and Post-Reform Performance and the Emerging Challenge, ISID Occasional Paper Series 2012/01.

Rahul, M. 2019. Never Done, Poorly Paid, and Vanishing: Female Employment and Labour Force Participation in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(19).

Rao, D.T. 2007. Economic Reforms: Lofty Rhetoric. Hallucinated Politics and Electoral Backlash, Review of Development and Changes 12 (1): 129–138.

Rao, C.H.H., and R. Radhakrishna. 1999. National Food Security: Policy Perspective for India’. In Food Security Diversification and Resource Management: Refocusing of Agriculture, ed. G.H. Peter and J.V. Braun. Ashgate: International Association of Agricultural Economics.

Reddy, A. 2013. Trends in Rural Wage Rates: Whether India Reached Lewis Turning Point. Trends in Rural Wage Rates: Whether India Reached Lewis Turning Point.

Rodrik, D., and A. Subramanian. 2005. From ‘Hindu Growth’ to Productivity Surge: The Mystery of the Indian Growth Transition. IMF Staff Papers 52 (2): 193–228.

Roy, Satyaki. 2016. Faltering Manufacturing Growth and Employment: Is ‘Making’the Answer? Economic & Political Weekly 51 (13): 35–42.

Roy Choudhury, P., and B. Chatterjee. 2015. Analyzing “Jobless Growth” in Post-Liberalisation India: A Decomposition Approach. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 58 (4): 577–608.

Saha, Partha, Ankita Gandhi, Kamala Devi and Sharmistha Sinha. 2013. Low Female Employment in a Period of High Growth: Insights from Primary Survey in Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat, IAMR Report No. 9/2013, Institute of Applied Manpower Research, Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi.

Singh, P., and S. Kumar. 2021. Demographic Dividend in the Age of Neoliberal Capitalism: An Analysis of Employment and Employability in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 64 (3): 595–619.

Singh, P., and F. Pattanaik. 2020. Unequal Reward for Equal Work? Understanding Women’s Work and Wage Discrimination in India Through the Meniscus of Social Hierarchy. Contemporary Voice of Dalit 12 (1): 19–36.

Srivastava, R. 2019. Emerging Dynamics of Labour Market Inequality in India: Migration, Informality, Segmentation and Social Discrimination. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 62: 147–171.

Srivastava, Nisha, and Ravi Srivastava. 2010. Women, Work and Employment Outcome in Rural India. Economic and Political Weekly 45 (28): 49–63.

Sundaram, K. 2001. Employment-Unemployment Situation in the Nineties: Some Results from NSS 55th Round Survey. Economic and Political Weekly 36 (11): 931–940.

Sundaram, K. 2013. Some Recent Trends in Population, Employment and Poverty in India: An Analysis. Indian Economic Review 48 (1): 83–128.

Thomas, J.J. 2012. India’s Labour Market During the 2000s; Surveying the Changes. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (51): 22.

Unni, J., and G. Raveendran. 2007. Growth of Employment (1993–94 to 2004–05): Illusion of Inclusiveness? Economic and Political Weekly 20: 196–199.

Vaidyanathan, A. 2007. Discussing “Inclusive Growth’ Ahead of Its Time”, Economic and Political Weekly, July 28

World Bank. 2009. Female Labor Force Participation in Turkey: Trends, Determinants and Policy Framework. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zhang, X., J. Yang, and S. Wang. 2011. China has Reached the Lewis Turning Point. China Economic Review 22: 542–554.

Funding

No supports received or sought from any funding organisation for preparation of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Views presented in the paper are personal views of the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Padhi, B., Tripati Rao, D. & Triveni, T. Discerning the Long-Term Pace and Patterns of Employment in India. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 66, 975–1004 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-023-00462-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-023-00462-5