Abstract

Migration is a significant factor in the organization of regional and urban space in India. In India, migration has been dominated by people from Eastern and Central regions moving to western and northwestern regions. On the other hand, Northeast has been known for in-migration and the conflicts arising from influx of migrants, but studies are lacking on the out-migration from the region. This study makes an attempt to study both inflow and outflow from the region and covers both internal and international migration. In this study, the Northeast India consists of the seven states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. Each state of the region shares an international boundary. The paper uses data from Census 2011 and has tried to study the magnitude of inflows to the region as well as the outflows from the region at the state level and also the reasons for migration. The state of Manipur is unique in the entire Northeast as outflow is three times higher than the inflow in the state. Assam is losing population due to internal migration to other states of India but compensated by international migration. The state of Assam presents a balanced ratio of inflow and outflow as stands in 2011 contrary to the popular perception that the state is gaining population inundated by immigration. The rest of the states of Northeast are gaining population predominantly due to internal migration, whereas Tripura gained population more from international compared to internal migration. The paper throws light on the combined impact of internal and international migration in the Northeast region which is generally lacking in migration studies on Northeast relevant for economic policy and political decision making. It also makes an assessment of reverse flows during the pandemic and lockdown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Migration from one area to another in search of improved livelihood is a key feature of human history. While some regions and sectors fall behind in their capacity to support populations, others move ahead and people migrate to access emerging opportunities. Migration has become a universal phenomenon in modern times. Due to the expansion of transport and communication, it has become a part of worldwide process of urbanization and industrialization. In most countries, it has been observed that industrialization and economic development have been accompanied by large-scale movements of people from villages to towns, from towns to other towns and from one country to another country.

From the demographic point of view, migration is one of the three basic components of population growth of any area, the other being fertility and mortality. But whereas both fertility and mortality operate within the biological framework, migration does not. It influences size, composition and distribution of population. More importantly, migration influences the social, political and economic life of the people.

Indian Constitution provides basic freedom to move to any part of the country, right to reside and earn livelihood of their choice. Thus, migrants are not required to seek permission or register either at the place of origin or at the place of destination (Bhagat 2008). A number of economic, social, cultural and political factors play an important role in the decision to move. The effects of these factors vary over time and place.

Analysis of migration pattern is important to understand the changes taking place in the people’s movement within the country. It is the most volatile component of population growth and most sensitive to economic, political and cultural factors (Singh 1998). Proper understanding of the patterns of migration would help in the estimation of future population redistribution. The reliability and dependability of these estimates depend much on the consideration of all the temporal factors of birth, death and internal migration on which population grows in its finest precision (Chakravarty 1997). Several studies (Davis 1951; Bose 1977; Premi 1990; Zachariah 1964; Srivastava 2011; Bell et al. 2015; Kone et al. 2018) found that intensity of interstate migration in India was low but pointed the fact that it is a significant component of labor mobility. Demographically when regional fertility and mortality differentials decline, migration becomes the foremost component influencing the redistribution of population as well (Beck 1985). The major concern of this paper is to examine the inflow and outflow of people from Northeast India which has been in the center of political turmoil surrounding the issues of migration. Researchers hardly examine the internal and international migration data together, and this has also happened in respect of Northeast India. Further, census data are ignored or looked upon as doubtful without carrying out detailed and rigorous analysis. This study examines internal and international migration in the Northeast, reasons of migration and also analyses outflow from the region, and the reverse migration in the wake of COVID-19 and lockdown in the country.

2 Migration Data and Methodology

Migration is defined as a move from one migration defining area to another, usually crossing administrative boundaries made during a given migration interval and involving a change of residence (UN 1993). The change in residence can take place either permanent or semi-permanent or temporary basis (Premi 1990). Internal migration involves a change of residence within national borders. Until 1951, district was the migration defining area (MDA), implying that a person was considered a migrant in India only if he or she has changed residence from the district of birth to another district or a state. Since 1961, data on migration have been collected by considering each revenue village or urban settlement as a separate unit. A person is considered as a migrant if birthplace is different from place of enumeration.

In 1971 census, an additional question on place of last residence was introduced to collect migration data. Since then, census provides data on migrants based on place of birth (POB) and place of last residence (POLR). If the place of birth or place of last residence is different from the place of enumeration, a person is defined as a migrant. On the other hand, if the place of birth or place of last residence and place of enumeration is the same, the person is a non-migrant.

Migration can be measured either as events or transitions. The former are normally associated with population registers, which record individual moves, while the latter generally derived from censuses compare place of residence at two points in time. A survey shows that census is the largest source of information on internal migration at the cross-country level. A study shows that 138 countries collected information on internal migration in their censuses compared to 35 through registers and 22 from surveys (Bell 2003). Apart from census data on migration, this also incorporates various other studies carried out in more recent years to highlight the emerging trends to and from Northeast region.

3 Methodology

The Northeast is defined states consisting of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura in this study. These states form a gateway from India into South Asia, bordering Bhutan, China, Bangladesh and Myanmar.

To simplify the analysis, the states and Union Territories of India have been divided into six regions. The regions are:

-

(a)

North India: consisting of states and Union Territories, namely Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttaranchal, Haryana, Rajasthan, Delhi and Chandigarh.

-

(b)

West India: consisting of states and Union Territories, namely Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Daman and Diu, Dadra Nagar Haveli and Lakshadweep.

-

(c)

Central India: consisting of states and Union Territories, namely Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

-

(d)

South India: consisting of states and Union Territories, namely Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry.

-

(e)

East India: consisting of states and Union Territories, namely Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, Sikkim, West Bengal and Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

-

(f)

Northeast India: consisting of states, namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura.

Inflow to Northeast represents the in-migration to the defined states and outflow stands for out-migration from the region to various other states of India. In addition, immigration to Northeast has been also studied. Due to non-availability of data on emigration from the census, this is relatively a little known area of migration research for the Northeast. Data on reverse migration during the nationwide lockdown in the wake of COVID-19 were collected from different media and government sources.

4 Migration in Northeast India

The history of Northeastern part of India has been a history of migration. Before written history, the flow was mainly from the eastern direction, so that most of the ethnicities that today claim to be the autochthons can trace their ancestries to the east of India, mostly to Southeast Asia. Subsequently, people from the western direction also began coming in and the communities like the caste Hindu Axamiya—speaking population of Assam often trace their origin back to parts of mainland India (Goswami 2007). There has been a consistent flow of migration in this region because of employment opportunities in tea garden, availability of cultivable land and other related factors (Bandyopadhyay and Chakraborty 1999). Studies also revealed that these states are experiencing higher influx of migration, both internal migration and international migration. Mukherjee (1982) has found substantial in-migration in Northeastern states. Census 2011 recorded 14.9 million migrants in the Northeast, which constitute about 33% of the total population in the region. This shows an increase of about 5.0 million migrants from census 2001.

Northeast India has been the significant receiver of migrants in the past being the frontier region with low density of population. Table 1 gives the magnitude of migration in the Northeast states based on the definition of place of birth and place of last residence. There is not much difference in migration based on the two definitions. Expected under-estimation of migration by place of birth definition could not be seen in the region as well as for the country as a whole. In the country about 450 million people, constituting 37% of the population are migrants. It is observed that there is less mobility in Northeast region as compared to the country average. About one-third of people in the region are migrants as compared to about 37% country average. Arunachal Pradesh is the only state having a higher percentage of migrants than the country average with about 45% of population as migrants. The lowest mobility is observed in the states of Manipur, Meghalaya and Nagaland, where just about one-fourth are migrants.

Table 2 shows the streams of migration in the Northeast states based on the definition of place of last residence. It is seen that migration within the same district dominates in all the states. About 60% of migrants in the country have moved within the same district. Among the Northeast states, Nagaland and Mizoram Arunachal Pradesh have less proportion of migrants moving within the district of enumeration. In the states of Manipur, Meghalaya and Assam, about two-thirds of the migrants have moved within the district of enumeration. The three states of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Meghalaya indicate a large inflow of migrants from other states. Interstate migrants contribute as much as 22% in Arunachal Pradesh as compared to a meager 3.0% in Manipur. Assam is the only state where the share of interstate migration from rest of the country is higher than share of interstate migration within the region. It is observed that international migration to the Northeast India constitutes about 2.5% of total migrants in the region. The share of international migrants in the state of Tripura is 17% of total migrants, much higher than the share of interstate migrants.

Table 3 gives the sex-wise distribution of migrants in the Northeast states by the streams of migration. The sex ratio is calculated as the number of female migrants per 1000 male migrants. The national figure shows feminization of migration irrespective of streams of migration. There are 2120 female migrants for each 1000 male migrants in the country, with greater dominance in migration within the state of enumeration. Compared to the country average, there is less dominance of female migration in Northeast region. Dominance of female migrants in the state of Assam, Manipur and Tripura pulled up the region migrant sex ratio to 1681. In all states of the region, it is observed that male migrants dominate the flow of interstate migration from states outside the region. Sex ratio of interstate migration from rest of India is 866 female migrants per 1000 male migrants, with the highest 949 in Assam and lowest 494 in Mizoram. The states of Meghalaya and Nagaland have more male migrants than female migrants. Meghalaya with a migrant sex ratio of 874 showed dominance of female migrants only among interstate migrants from within the region. In contrast, Nagaland has more of female migrants only among intradistrict migrants.

5 Interstate Inflows into Northeast

Northeast region has a plethora of small ethnic communities, each fiercely protecting their respective identities. In recent times, there has been apprehension of being overwhelmed by huge inflows of migrants. National Register of Citizens has been conducted in Assam. Many states have demanded that Inner Line Permit be established to restrict and manage inflows of migrants to the region.

Table 4 shows the percentage distribution of migration to Northeast states from various regions of the country. The contribution of migrants from each region of the country has also been given for comparison. It is seen that more than one-fourth of the migrants in the country have originated from the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. East India and North India have each contributed about one-fifth of total migrants. The remaining one-third of migrants have originated from South India, other countries, West India and Northeast India combined. The contribution of Northeast is a minimal 1.7% in the total migration of the country. Taking the Northeast as a region, it is seen that 42% of migrants have originated from other countries. Another 42% of migrants to the region have originated from the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha, Sikkim and Andaman & Nicobar Islands. The remaining regions have contributed just 16% of migrants to Northeast India. State-wise differentials of migrant inflows can be observed from the table. In all states but Tripura and Assam, majority of the inflow of migrants have been from other states of Northeast India. In Tripura, about 72% of migrants have come from other countries and just 16% from other Northeast states. In Assam, 23% of migrants have come from neighboring states of Northeast and 43% have migrated from states of East India. Except Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Nagaland, in the rest of the states of Northeast, the contribution of international migrants has been higher than the national average. It is highest in Tripura followed by Mizoram, Assam and Manipur. The share of international migration has been found to be higher than the share of migration from regions of India, but East India, in all the states of Northeast.

Table 5 gives the percentage distribution of the reasons for migrating to Northeast region. In the table, only migration from other states and countries has been considered. Reasons for migration have been presented by originating regions. Northeast total is the aggregate of migrants from all region, while the national average indicated the reasons for migration among interstate and international migrants. The national average shows marriage as the most important reason for migration, followed by moved with household and work. Migration to Northeast has mainly moved with household and for work. Marriage is the third important reason for migrating to Northeast. About one-third of migrants from East, South and Central India have moved for work, as compared to just 9.0% of international migrants stating work as reason for migration. Forty percent of international migrants have moved with family.

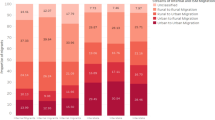

The percentage distribution of rural urban status of interstate migration flow to Northeast is given in Fig. 1. It is observed that about 68% of interstate migration to Northeast have originated from rural areas, as compared to about 32% from urban areas. Greater proportion of migrants from East and Central regions of India have moved from rural areas. Rural to rural migration has been observed to be the dominating stream of migration. It is seen that about 62% of interstate migrants to Northeast have moved to urban areas. It is seen that irrespective of rural and urban status of place of origin, interstate migration to Northeast has been urban centric.

6 Immigration in Northeast India

Studies on international migration have gained more importance lately with the improvement in trade and infrastructure. It assumes greater importance in Northeast India as all states in the region share border with another country. Many neighboring countries are much closer in distance than many of the other regions in India. It is not possible to study the magnitude or characteristics of people moving from the region to other countries using data from Census. However, the characteristics of people migrating to Northeast states can be analyzed.

Table 6 gives the distribution and magnitude of international migration in Northeast region based on the place of last residence. The number of international migrants in Northeast India has declined to 376 thousand in 2011 from about 444 thousand in 2001. There has been 18% decline in the inflow of international migrant to the region in 2011 as compared to 2001. About 59% of international migrants in the region have moved to the state of Tripura. Another 29% migrated to Assam and the remaining 12% are divided among the remaining five states. About three-fourth of international migrants in the Northeast moved from Bangladesh, 6% from Nepal, 4% from Myanmar and the rest from other countries. Migration from Bangladesh constitutes the major contributor of international migration in the states of Tripura, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. International migration in Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya is dominated by Nepali migrants, while migration from Myanmar dominates the international flow in Mizoram.

Table 7 explores the reasons for international migration in the Northeast states. Moved with household (40%) emerged as the most important reason for migrating to Northeast India followed by ‘others’ reason (32%). About 9% of the international migrants have moved for work reasons, while around 18% have moved for the reason of marriage. Migration for work is observed highest in the state of Nagaland (38%), followed by Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram (28% each) and Meghalaya (17%). The limited availability of data in the Census does not allow the analysis of reasons for migration by the country of origin. Yet, the finding seems to indicate more migrants from Nepal and Myanmar have migrated for work related reasons than migrants from Bangladesh.

7 Interstate Outflows from Northeast

The following section discusses the magnitude and characteristics of out-migration from Northeast India. Census 2011 recorded a little over one million out-migrants from the seven states of Northeast India. Out-migrants constitute 2.2% of Northeast population. The distribution of out-migrants from Northeast states is given in Table 8.

An understanding of out-migration from Northeast to different regions of the country would facilitate a better understanding of the inflow to Northeast India. A state-wise comparison shows that a large percentage of out-migrants migrated to other states within the Northeast region. Except Assam, interstate migration within the region constitutes the majority for all states of Northeast. Migration to states within the region ranges from about 84% from Mizoram to 38% from Assam. States of East India are observed to be the preferred destination with more than one-fourth of migrants from Assam and Tripura moving to this region. Migrants from other states like Meghalaya, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh have also moved to East Indian states. North Indian states have been observed to be the next preferred destination for migrants from Northeast, with significant migration from the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Nagaland. South India is the next destination with significant migration from Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh. Migration from Northeast states to West and Central Indian states has been minimal.

To better understand out-migration from the Northeast, it is necessary to study the different reasons for out-migration from the region. Table 9 provides the distribution of the reasons of interstate out-migration by the states of Northeast India. ‘Moved with household,’ work and marriage have emerged as the important reasons for out-migrating from Northeast region. About 28% of out-migrants from the region have moved with household and about 25% each for work and marriage. About 4% have moved out for education, and 17% have moved out of the region for ‘others’ reasons. A state-wise comparison reveals that 28% of out-migrants from Assam have moved for work related reasons followed by Manipur with about 25%. The remaining states have lesser percentage of migrants moving for work related reasons. The least is observed for the state of Mizoram with a meager 9.0% moving out for work related reasons.

Figure 2 gives the percentage distribution of rural urban status of out-migration from the Northeast. It has been observed about 52% of the migrants moving out from the region have originated from urban areas. Urban to urban migration has emerged as the most important stream of migration from Northeast to other regions of the country. Urban centric migration from the Northeast has been observed as about 68% of total out-migrants have moved to urban areas.

Table 10 gives the percentage share of migration from Northeast to selected urban agglomerates. Migration within the region has not been considered in the table. It is observed that about 526 thousand migrants have moved out of the region, with Assam contributing about 406 migrants. More than one-fourth of migrants from the region have migrated to the six urban agglomerates. About 47% of migrants from the states of Tripura and Manipur have migrated to the six urban agglomerates. Among urban agglomerates, Kolkata has attracted the highest number of migrants from Northeast, followed by NCT of Delhi, Bangalore and Greater Mumbai.

Table 11 provides out-migration ratio for Northeast. The ratio has been calculated as the number of outflows divided by inflows. A value of one signifies a balance between out-migration and in-migration. A value lesser than one would indicates net-migration to states and region. The ratio of interstate migration within Northeast considered the interstate flows between the states within the region. Similarly, the ratio of interstate flows between Northeast states and other states outside the region has been presented as rest of India. Ratio of total inflows has added international migration to interstate flows in the computation. It is observed that Manipur and Assam are the out-migrating states, while the remaining states gained migrants. The state of Manipur depicted the largest number of outflow per inflow. On an average, more than three migrants moved out of Manipur for every migrant that moved into the state. Assam has a ratio of 1.82 for interstate migration within Northeast and 1.14 for interstate flows with rest of the country. The ratio declined to about one if international migration is considered. The state of Arunachal Pradesh, with a value of 0.23, 0.36 and 0.25, showed that for every hundred migrants that moved to the state, only 25 to 36 moved out of the state. Tripura has a balanced inflows and outflows if interstate migration has been considered. With the inclusion of international migration, it is seen that the state showed a huge gain of migrants. Similar conclusion is observed for the region as a whole. Considering interstate migration only, Northeast region lost about nine thousand migrants. With the inclusion of international migration, the region gained about 367 thousand. With the unavailability of data on migration from the region to other countries, the figure could be overestimated. However, such findings continue to highlight the importance of international migration in the region.

8 Recent Flows, Reverse Flows and the Pandemic

Since the conduct of census in 2011, there have been various studies that indicate the shift of Northeast migration from the north to the south. Migration from Northeast to NCT of Delhi has declined by 26% (Singh and Gandhiok 2019). There has been significant flow of Northeast migrants to Kerala (Narayana and Venkiteswaran 2013; Arya 2018), Chennai (Deori 2016; Kiruthiga and Magesh 2017; Douminthang and Xavier 2020) and Bangalore (Marchang 2018). South India has experienced fast industrialization, has higher wage rate and a relatively more tolerant community. This has attracted migrants from the Northeast in recent years.

With the announcement of national lockdown on March 25, 2020 due to Covid-19 pandemic, the migrants have been hit the hardest. Most of the migrants from Northeast are engaged in unorganized sectors. Shutting down of industries and business left the migrants with no source of income in places far away from their native place. The limited prospect of economic revival left the migrants with no choice but to turn back to their native places. With active participation from respective state governments, there has been mass return of migrants to their native places. Migrants from Northeast are not an exception. More than 138 Shramik Special trains transported nearly 1,88,000 stranded people to various states of Northeast (The Sentinel 2020). There also people who returned arranging their own transportation. In all, total return migrants during the period of lockdown were estimated to 512 thousand migrants have returned to Northeast from various states of India (see Table 12). This constitutes about half of out-migration from Northeast in 2011. This mass return migration to the Northeast was unprecedented. About 390 thousand migrants have returned to the state of Assam only—a state beleaguered due to immigration politics. Similar mass return of migrants could be seen for all states. The number of return migration in the month of June could not be known for Manipur. The huge inflow of return migrants to the Northeastern states has challenged the state governments, yet offers a window of opportunity to capitalize on the skills and experience of the returned migrants.

9 Summary and Conclusion

In recent times, migration from one place to another has emerged as an important component of population composition and change. Migration has influenced every aspect of life in the origin as well as the destination. The impact of migration has been felt particularly in the Northeast region of the country. In recent times, there has been apprehension of small ethnic communities of the region being overwhelmed by huge inflows of migrants and subsequent demand for restriction and management of migration.

The present study analyzed migration intensity in Northeast India using data from Census 2011. National average, wherever possible, has been provided for comparison. There is a low mobility within the states of Northeast region as compared to the rest of the country. Arunachal Pradesh is the only state having percentage of migrants higher than the country average. The lowest mobility within the state is observed in the states of Manipur, Meghalaya and Nagaland. While intradistrict migration dominates migration in the region, states like Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Meghalaya have a significant interstate migration as well. The share of immigrants in the state of Tripura is higher than the share of interstate migrants. Female migration dominates migration in the country as well as most of the states in Northeast. The states of Meghalaya and Nagaland have more male migrants compared to females.

States of Central India contributed more than one-fourth of migrants in the country. On the other hand, the contribution of Northeast is a minimal of 1.7% of total migration in the country. Taking the Northeast as a region, it is seen that majority of migrants have originated from other countries and the states of Eastern India. The contribution of immigrants has been observed to be relatively higher in Northeast India.

Marriage is the most important reason for migration in the country as a whole. In contrast, migration to Northeast states has been mainly moved with household and for work.

Census 2011 recorded a little over one million out-migrants from the seven states of Northeast India. Out-migrants constitute 2.2% of the population of Northeast. While 526 thousand have migrated out of the region, the remaining 428 thousand have migrated within the region. Except for the state of Assam, majority of out-migration has been within the states of Northeast. States of Eastern India is the next preferred destination for migration from Northeast, with Kolkata emerging as the most preferred urban agglomerate. ‘Moved with household,’ work and marriage have emerged as the important reasons for out-migrating from the region.

Rural to urban streams has been the important stream among interstate migration to Northeast. In contrast, out-migration from the region has been dominated by urban to urban migration.

Manipur and Assam are out-migrating states, while the remaining states gained migrants. While the states of Manipur depicted the largest number of outflow per inflow, Assam depicts a balanced outflow and inflow if international migration is considered. The state which has gained the maximum inflow per outflow is Arunachal Pradesh. If international migration is considered, the state of Tripura shows a huge gain of migrants. Similar conclusion is observed for the region as a whole. If international migration is not taken into consideration, the region is an out-migrating region. But including international migration, the region gained about 367 thousand. With the unavailability of data on emigration, the figure could be overestimated.

There has been decline in the inflow of immigrants to the Northeast in 2011 as compared to 2001. Majority of immigrants have moved to the state of Tripura and Assam. About three-fourth of immigrants in the Northeast moved from Bangladesh. Among immigrants, moved with household emerged as the most important reason for migrating to Northeast India followed by ‘others’ reason. Only a small proportion of immigrants have moved to the region for work reasons.

An assessment of the reverse flow in the wake of pandemic and nationwide lockdown imposed in the month of March shows that about half a million of interstate out-migrants returned constituting about 50% of interstate out-migrants from Northeast India. This opens up enormous challenges as well as a window of opportunity for the states of Northeast to capitalize on the skills and the experiences of the return migrants.

References

Arya, S. 2018. Domestic migrant workers in Kerala and their socio economic condition. Shanlax International Journal of Economics 6(1): 74–77.

Bandopadhaya, Sabari, and Debesh Chakraborty. 1999. Migration in the north-eastern region of India during 1901–1991: Size, trend, reason and impact. Demography India 28(1): 75–97.

Beck, A. J. 1985. The effects of spatial location on economic structure on interstate migration, U.M.I. Dissertation Information Service, University of Michigan, Michigan.

Bell, Martin. 2003. Comparing internal migration between countries: Measures, data sources and results. Paper presented in population Association of America 2003, Minneapolis, May 1–3, 2003.

Bell, M., E.C. Edwards, P. Ueffing, et al. 2015. Internal migration and development: Comparing migration intensities around the world. Population and Development Review 41(1): 33–58.

Bhagat, R.B. 2008. Assessing the measurement of internal migration in India. Asian Pacific Migration Journal 17(1): 91–102.

Census of India. 2011. Soft copy, India D-series, Migration Tables. Registrar General and Census commissioner, India.

Chakravarty, B. 1997. The census and the NSS data on internal migration. In Population statistics in India, ed. Ashish Bose, Davendra B. Gupta, and Gaurisankar Raychaudhuri. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd.

Chatterjee, Atreyi, and Ashish Bose. 1977. Demographic data on internal migration and urbanisation from census and NSS—An appraisal. In Population statistics in India, ed. Ashish Bose, Davendra B. Gupta, and Gaurisankar Raychaudhuri. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd.

Davis, K. 1951. The population of India and Pakistan. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Deori, Banti. 2016. A case of single female labour migrants working in the low-end service jobs from North-Eastern region to the metropolitan city Chennai, India. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 21(12): 20–25.

Douminthang Baite, N.S., and G.G. Xavier. 2020. Student migrants in India: A study on the North East Students in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. International Journal of Scientific Research 9(4): 35–39.

Kiruthiga, V., and R. Magesh. 2017. The migration of North East people towards Chennai—A case study. International Journal of Management Research and Business Strategy 6(2): 95–97.

Kone, Z.L., M.Y. Liu, A. Mattoo, et al. 2018. Internal borders and migration in India. Journal of Economic Geography 18(4): 729–759.

Marchang, R. 2018. Out-migration from North Eastern Region to cities: Unemployment, employability and job aspiration. Journal of Economic & Social Development 13(2): 43–53.

Mukherjee, S. 1982. Was there significant migration to Eastern India during 1971–81? Economic and Political Weekly XVII(22): 918–920.

Narayana, D., and C.S. Venkiteswaran. 2013. Domestic migrant labour in Kerala. Gulathi Institute of Finance and Taxation. Submitted to Labour and Rehabilitation Department Government of Kerala.

Premi, M.K. 1990. India. In International handbook on internal migration, ed. Charles B. Nam, William J. Serow, and David F. Sly. New York: Greenwood Press.

Singh, D.P. 1998. Internal migration in India: 1961–1991. Demography India 27(1): 245–261.

Singh, P., and J. Gandhiok. 2019. Fewer people from Northeast and Southern States making Delhi their Home. The Times of India, July 31, 2019. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/fewer-people-from-Northeast-and-southern-states-making-delhi-their-home/articleshow/70458576.cms. Accessed 30 July 2020.

Srivastava, Ravi. 2011. Labour migration in India: Recent trends, patterns and policy issues. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 54(3): 411–440.

The Sentinel, July 8, 2020. https://www.sentinelassam.com/guwahati-city/more-than-138-shramik-special-trains-reach-Northeast-487373. Accessed 30 July 2020.

U.N. 1993. Readings in population research and methodology. New York: The United Nations Population Fund.

Uddipana Goswami, 2007. Internal displacement, migration, and policy in Northeastern India. East West Center working paper no 8, 2007.

Zachariah, K.C. 1964. Historical study of internal migration in the Indian sub-continent, 1901–1931. Research Monograph 1, Demographic Training and Research Centre, Bombay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lusome, R., Bhagat, R.B. Migration in Northeast India: Inflows, Outflows and Reverse Flows during Pandemic. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 63, 1125–1141 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00278-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00278-7