Abstract

In this paper, we aim to understand whether low labour market returns to education in India are responsible for low female work participation. The National Sample Survey Office—Employment Unemployment Survey unit level data of India for the year 2011–2012 is used to examine the relationship between educational attainment and labour market participation through gender lens. Results show that women’s education has a U-shaped relationship with paid work participation. The probability to participate in the paid labour market increases with education levels higher than compulsory secondary schooling. The labour market returns to education are insignificant and low for lower levels of education, increasing significantly along the educational levels. Technical education equivalent to degree level or above has high returns for men and women. However, women with technical education have very low levels of participation. Vocational training also provides a positive return. Our results suggest that to increase participation, women need to be educated above secondary level and receive broader technical education and more vocational training.

Source: CensusInfo India 2011

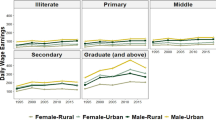

Source: Authors’ calculation from NSSO EUS: 50th Round (1993–1994), 55th Round (1999–2000), 61st Round (2004–2005), 66th (2009–2010) and 68th Round (2011–2012)

Source: Authors’ calculation from NSSO employment and unemployment surveys: 50th Round (1993–1994), 55th Round (1999–2000), 61st Round (2004–2005), 66th (2009–2010) and 68th Round (2011–2012)

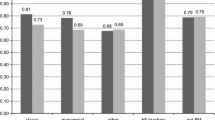

Source: Authors’ own calculation from NSS unit level data, 68th Round 2011–2012

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In a model involving possible LFP, the reservation wage rate is the minimum wage rate at which an agent will accept employment. The reservation wage rate is generally greater than zero because the agent’s alternatives to paid employment have positive value. The alternatives might be taking care of children (rather than paying for child care services), pursuing education, or simple leisure.

We have compared our results to the Discussion Paper 8 titled ‘The Indian Labour Market: A Gender Perspective’ prepared for ‘Progress of the World’s Women 2015–2016’, UN Women.

Results of the probit regressions for age categories, 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55plus, 15–24, 25–34, 35–59 are available on request from the authors.

Self-Employed work may have an impact on the decision to participate in paid work, which led us to create a dummy variable for self-employed work and incorporate it in the participation equation. However, existence of cum hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy seems to be making the variable to be dropped as it shows perfect failure. We feel that the limitation is due to the NSSO data availability and this might be better addressed by Randomised Trial Controls.

Some of the covariates are likely to be endogenous as there might be underlying factors simultaneously affecting the covariates and the dependent variable. This might particularly be the case for marital status and number of children. Such endogeneity will bias the coefficients on marital status and children downwards (as the marriage decision and the decision to have children might be jointly determined with the decision not to work). When interpreting the coefficients, we must keep in mind these potential biases (Klasen and Pieters 2012).

Reservation to job placements and enrolment in education in India is an action designed to improve the well-being of backward and under-represented communities defined primarily by their caste. It’s a phenomenon that commenced with the coming into force of the Indian Constitution. This reservation system is also applicable to entry into Government Service.

In India, women from low educated, low income and low caste households can work (even in menial jobs) without facing disapproval from the society. Caste and Class diktats, however, forbid women from highly educated, high income class and high caste households from doing such work. This is the ‘Sanskritisation’ process.

In an attempt by the central government of India to make the community creche dream a reality for working women of all strata and enhance access by bringing it closer to home and work space, the ministry of women and child development is in the process of finalising a National Programme for Creche and Day Care Facilities. The draft proposes that creche facilities meant for children of age 6 months to 6 years should not be more than one and half kilometres from either the home of child or the workspace of mother (http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/national-creche-policy-to-bring-day-care-closer-to-home/articleshow/57928206.cms).

References

Afridi, F., T. Dinkelman, and K. Mahajan. 2016. Why are fewer married women joining the work force in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades. Journal of Population Economics 31(3): 783–818.

Behrman, J.R., A.D. Foster, M.R. Rosenzweig, and P. Vashishtha. 1999. Women’s schooling, home teaching, and economic growth. Journal of Political Economy 107(4): 682–714.

Bettio, F., and P. Villa. 1998. A mediterranean perspective on the break-down of the relationship between participation and fertility. Cambridge Journal of Economics 22(2): 137–171.

Cameron, L.A., J.M. Dowling, and C. Worswick. 2001. Education and labor market participation of women in Asia: Evidence from five countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change 49(3): 459–477.

Chaudhary, R., and S.S. Verick. 2014. Female labour force participation in India and beyond. ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series.

Chen, M., and J. Drèze. 1992. Widows and health in rural North India. Economic and Political Weekly 27(43–44): 24–31.

Chowdhury, S. 2011. Employment in India: What does the latest data show? Economic and Political Weekly XLVI(32): 23–26.

Das, M.B. 2006. Do traditional axes of exclusion affect labour market outcomes in India? Social Development Papers, South Asia Series, No. 97, Washington DC, World Bank.

Das, M.B., and S. Desai. 2003. Why are educated women less likely to be employed in India? Testing competing hypotheses. Social Protection Discussion Papers Series, No. 0313, Social Protection Unit, Human Development Network, The World Bank.

Dasgupta, P., and B. Goldar. 2005. Female labour supply in rural India: An econometric analysis. Indian Journal of Labor Economics 49(2): 293.

Divakaran, S. 1996. Gender based wage and job discrimination in urban India. Indian Journal of Labour Economics 39(2): 327–340.

Duraiswamy, P. 2002. Changes in returns to education in India, 1983–1994: By gender, age-cohort and location. Economics of Education Review 21(6): 609–622.

Ghose, A.K. 2004. The employment challenge in India. Economic and Political Weekly 39(48): 5106–5116.

Goldin, C. 1995. The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history. In Investment in women’s human capital and economic development, ed. T.P. Schultz, 61–90. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Guiso, L., P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales. 2003. People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics 50(1): 225–282.

Heckman, J. 1979. Sample selection bias as specification error. Econometrica 47(1): 153–161.

Hirway, I. 2012. Missing labour: An explanation. Economic and Political Weekly 47(37): 67–72.

Kannan, K.P., and G. Raveendran. 2012. Counting and profiling the missing labour force. Economic and Political Weekly 47(6): 77–80.

Kapsos, S., A. Silbermann, and E. Bourmpoula. 2014. Why is female labour force participation declining so sharply in India? ILO Research Paper No. 10.

Kingdon, G. 1998. Does the labour market explain lower female schooling in India? The Journal of Development Studies 35(1): 39–65.

Kingdon, G., and N. Theopold. 2008. Do returns to education matter to schooling participation? Evidence from India. Education Economics 16(4): 329–350.

Kingdon, G., and J. Unni. 2001. Education and women’s labour market outcome in India. Education Economics 9(2): 173–195.

Klasen, S., and J. Pieters. 2012. Push or pull? Drivers of female labor force participation during India’s economic boom. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6395.

Klasen, S., and J. Pieters. 2015. What explains the stagnation of female labor force partcipation in urban India? World Bank Economic Review 29(3): 449–478.

Lam, D., and S. Duryea. 1999. Effects of schooling on fertility, labor supply, and investments in children, with evidence from Brazil. Journal of Human Resources 34(1): 160192.

Mazumdar, I., and N. Neetha. 2011. Gender dimensions: Employment trends in India, 1993–1994 to 2009–2010. Economic and Political Weekly 46(43): 118–126.

Duraisamy, M., and P. Duraisamy. 1993. Returns to scientific and technical education in India. Margin 7(1): 396–406.

Mammen, K., and C. Paxson. 2008. Women's work and economic development. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(4): 141–164.

Masood, T., and M. Ahmad. 2009. An econometric analysis of inter-state variations in women’s labour force participation in India. mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de.

Mehrotra, S., A. Gandhi, B.K. Sahoo, and P. Saha. 2012. Creating employment in the twelfth five-year plan. Economic and Political Weekly XLVII(19): 63–73.

Munshi, K., and M. Rosenzweig. 2006. Traditional institutions meet the modern world: Caste, gender and schooling choice in a globalizing economy. American Economic Review 96(4): 1225–1252.

Neff, D., K. Sen, and V. Kling. 2012. The puzzling decline in rural women’s labor force participation in India: A reexamination. GIGA Working Papers, No. 196, May 2012.

NSSO. 2011–2012. Employment and unemployment situation in India, 68th Round, Report No. 554. Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India.

OECD Employment Outlook. 1989. Educational attainment of the labour force, Chapter-2.

Olsen, W., and S. Mehta. 2006. A pluralist account of labour participation in India. GPRG-WPS-042.

Palaz, S., E. Karagal, and K. Masatci. 2001. The effect of education on labour force participation rate: The case of TURKEY. www.academia.edu/…/The_Effect_of_Education_on_Labour_Force_Participation_Ra.

Pastore, F., and A. Verashchagina. 2006. Private returns to human capital over transition: A case study of Belarus. Economics of Education Review 25(1): 91–107.

Pastore, F., and S. Tenaglia. 2013. Ora et non Labora? A test of the impact of religion on female labor supply. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 7356.

Pradhan, B.K., S.K. Singh, and A. Mitra. 2014. Female labour supply in a developing economy: A tale from a primary survey. Journal of International Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2994.

Psacharopoulos, G. 1994. Returns to investment in education: A global update. World Development 22(9): 1325–1343.

Psacharopoulos, G., and P. Tzannatos. 1992. Women’s employment and pay in Latin America. Washington, DC: World Bank Regional and Sectoral Studies.

Rangarajan, C., I.P. Kaul, and Seema. 2011. Where is the missing labour force? Economic and Political Weekly 46(39): 68–72.

Raveendran, G. 2016. The Indian labour market: A gender perspective. Discussion paper-8, Prepared for Progress of the World’s Women 2015–16. UN Women.

Schultz, T.P. 1994. Human capital investment in women and men: Micro and macro evidence of economic returns. Occasional Papers, No. 44. International Centre for Economic Growth.

Shaw, A. 2013. Employment trends in India. Economic and Political Weekly 48(42): 23–25.

Siddiqui, M.Z.S., K. Lahiri-Dutt, S. Lockie, and B. Pritchard. 2017. Reconsidering women’s work in rural India analysis of NSSO data, 2004–05 and 2011–12. Economic and Political Weekly L II(1): 45–52.

Srivastava, N., and R. Srivastava. 2010. Women, work and employment outcomes in rural India. Economic and Political Weekly 45(28): 49–63.

Sudarshan, R.M. 2014. Enabling women’s work. ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series.

Tansel, A. 2004. Education and labor market outcomes in Turkey. World Bank Report. Turkey: Education Sector Study, June.

Unni, J. 1996. Returns to education by gender among wage employees in urban India. Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, July.

Verick, Sher S. 2017. The puzzles and contradictions of the Indian labour market: What will the future of work look like? Asarc Working Paper 2017/02.

World Development Report. 2012. Gender equality and development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanjilal-Bhaduri, S., Pastore, F. Returns to Education and Female Participation Nexus: Evidence from India. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 61, 515–536 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-018-0143-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-018-0143-2