Abstract

The pump structure may involve using fins on the impeller discs to reduce axial thrust. The fins are also used to reduce pressure acting on the discharge-side stuffing box, throw mechanical impurities away and protect the seal against mechanical impurities at the pump impeller inlet. Extensive laboratory tests were performed on finned discs at the water centrifugal flow for different fin widths and gaps between fins and the casing and for different water flow rates. The resulting change in power consumption was determined compared to unfinned discs. The analysis results indicate that fitting the disc with fins involves an increase in power consumption. The consumption rise depends on the centrifugal volumetric flow rate, the fin width and the size of the gap. The dependence of power consumption on the gap size is non-monotonic—the gap can be optimized to minimize power consumption. The determination of the rise in the consumption of power resulting from fitting the disc with fins and depending on the centrifugal volumetric flow rate is an original outcome of the analysis presented in this paper. The dependence was defined for fins with different values of width and for different sizes of gap. The presented results of the testing can be used in the analysis of power consumption of both finned and unfinned rotating discs. The analysis of power consumption in the impeller pump axial thrust balancing system using balancing vanes is another example of the application of the obtained results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A rotating disc mounted on a shaft is a common structural component of a machine. The disc can be either a self-contained device or a part of another structural element. In order to maintain the disc rotational motion, torque has to be applied. Frictional forces can cause energy dissipation. If the rotating disc is surrounded by a fluid (gas or liquid), friction forces resulting from the fluid viscosity are generated on the fluid–disc interface.

The friction forces are affected considerably by the shape of the disc surface, which can be smooth and flat. However, the surface can be shaped in different ways. One particular form of the element is a disc with fins. Due to the fins and viscosity, the fluid surrounding the disc starts to rotate.

The friction accompanying the fluid rotational motion results in energy dissipation, which is an unfavourable phenomenon. In some cases, however, a situation like this is fairly desirable (e.g. hydraulic brakes). The phenomenon of friction on the liquid-rotating disc interface is also present in disc pumps.

In impeller pumps, balancing vanes are used on the impeller rear disc to reduce axial thrust. The use of vanes (fins) increases the speed of the liquid rotation in the space after the impeller. The effect is a change in pressure distribution and reduction in axial thrust. The balancing vanes on the last stage impeller have another beneficial effect—they reduce the pressure acting on the discharge-side stuffing box (Wilk and Wilk 2001). Moreover, in the case of mechanically polluted liquids, the fins on the impeller rear disc throw mechanical impurities away in the centrifugal direction, thus protecting the stuffing box. The vanes protecting the seal by throwing mechanical impurities away at the impeller inlet are made as finned elements of the disc (Cao et al. 2015; Wilk and Wilk 1996a).

The application of fins changes the pressure distribution, produces the moment of friction and causes energy dissipation. The issues related to the distribution of pressure in the turbomachinery near-impeller space are thoroughly discussed in reference literature. In the case of pumps, the problem involves analysing axial thrust characteristics (Bhatia 2014; Dong and Chu 2016a, b; Gantar et al. 2002; Golovin et al. 1989; Godbole et al. 2012; Hong et al. 2013; Iino et al. 1980; Jedral 2001; Kalinichenko and Suprun 2012; Karaskiewicz 2013; Kim and Palazzolo 2016; Lefor et al. 2015; Lugova et al. 2014; Matsui and Mugiyama 2009; Piesche 1989; Rohatgi and Reshotko 1974; Shimura et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013; Wilk 2003b, 2009; Zhou et al. 2013) or volume losses resulting from untight sealing (Ayad et al. 2016; Bhatia 2014; Cao et al. 2015; Gantar et al. 2002; Kim and Palazzolo 2016; Lefor et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016; Shimura et al. 2012; Torabi and Nourbakhsh 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Wilk and Wilk 2001). So far, experimental (Ayad et al. 2016; Dong and Chu 2016b; Gantar et al. 2002; Godbole et al. 2012; Hong et al. 2013; Iino et al. 1980; Lefor et al. 2015; Nemdili and Hellmann 2007; Owen and Pincombe 1980; Piesche 1989; Wilk and Wilk 1996b; Wilk 2008; Zhou et al. 2013) and computational (Ayad et al. 2016; Cao et al. 2015, 2016; Dong and Chu 2016b; Dykas and Wilk 2008; Golovin et al. 1989; Hong et al. 2013; Karaskiewicz 2013; Kim and Palazzolo 2016; Lefor et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016; Matsui and Mugiyama 2009; Piesche 1989; Rohatgi and Reshotko 1974; Shimura et al. 2012; Torabi and Nourbakhsh 2016; Watanabe et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2013) tests have been carried out. Selected works are devoted to cases of the centripetal or centrifugal flow (Ayad et al. 2016; Bhatia 2014; Cao et al. 2015; Dong and Chu 2016a; Gantar et al. 2002; Golovin et al. 1989; Iino et al. 1980; Karaskiewicz 2013; Lefor et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016; Matsui and Mugiyama 2009; Owen and Pincombe 1980; Piesche 1989; Rohatgi and Reshotko 1974; Shimura et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013; Wilk and Wilk 1996b).

Much less attention (Bhatia 2014; Daqiqshirazi et al. 2014; Dong and Chu 2016a; El-Naggar 2013; Torabi and Nourbakhsh 2016) is given to the problem of energy consumption caused by the fluid friction against a rotating disc. The basic reference literature items (Daily and Nece 1960a, b; Gulich 2014; Lazarkiewicz and Troskolanski 1965; Piesche 1989; Pfleiderer 1961; Rohatgi and Reshotko 1974; Stepanoff 1957) present relations for smooth-surfaced discs, whereas in many cases it is the disc fins that produce a change in the distribution of pressure. Tests and analyses should be performed taking account of the centrifugal flow, as this phenomenon occurs in multistage pumps where the axial thrust issue requires special attention. However, there are only a few publications concerning this particular problem (Golovin et al. 1989; Piesche 1989; Rohatgi and Reshotko 1974; Wilk and Wilk 1996b; Wilk 2003a, b).

This paper presents extensive laboratory tests carried out to find the power consumed by a disc rotating in water.

The tests were made for an unfinned disc and for discs with fins on one side.

The tests were conducted for fins with a different width and for different sizes of the gap between the fins and the casing wall.

What makes the tests unique is the fact that they were performed for induced centrifugal flows of water with varied flow rates around the disc.

The measurement results presented in this paper can find wide applications. They can be used to calculate the power loss in devices with finned discs rotating in water, also in the case of flows taking place in the space around the disc. In particular, the results of the analyses presented herein can be used in the design and optimization of the axial thrust balancing system using balancing vanes in impeller pumps.

2 The Laboratory Testing Concept

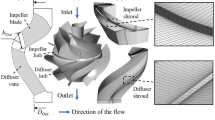

The discs of the centrifugal pump impeller are usually flat, but balancing vanes (fins) are placed on rear discs of the impeller in the case of the axial thrust balancing system.

In multistage pumps, the working liquid flows through the interstage sealing systems from one stage to another, which causes a centrifugal flow in the space between the impeller rear disc and the pump casing.

The information on the power loss resulting from the rotational motion of the flat or finned disc in the liquid is necessary to establish the power required to drive the pump and to determine the pump efficiency.

Therefore, it was decided to perform the tests in a manner corresponding to conditions occurring in centrifugal pumps.

The power measurement tests were made for flat and finned discs with a centrifugal flow in the finned space for different values of the fin width and size of the gap between the fins and the wall. Owing to that, the test results allow optimization of the fin width and the disc positioning relative to the casing.

An analysis of the structure of commercially available impeller pumps was conducted, and on this basis, the range of the test parameters was established.

The test stand was designed, and the testing parameters were selected according to the assumed concept of the testing.

3 The Test Stand

The impeller rear discs are used in centrifugal pumps as an element of the axial thrust balancing system. For this reason, an attempt was made to shape the test stand flow part so that its geometry should be similar to this particular component of the multistage pump flow system.

The essential element of the test stand is a disc with the shape of the rear disc of the centrifugal pump impeller. The disc main dimensions are given in Fig. 1.

Four different discs were tested. One had no fins at all. The other three had fins with a different width b.

The tests were performed under laboratory conditions on a purpose-built test stand. The test stand cross section is presented in Fig. 2.

The disc is mounted on a horizontal shaft. It is placed in a cavity limited by two flat walls perpendicular to the shaft axis and a cylindrical surface coaxial with the rotation axis.

The test stand is fitted with an inflow and outflow connector to make it possible to supply the stand with water and induce a centrifugal flow in the space on the disc finned-surface side.

The inflow connector is close to the hub. Water flows through the surge chamber and then, through an axially symmetric gap along the shaft, into the cavity where the disc rotates. Having passed along the disc, water flows out through an outflow hole located on the cylindrical surface.

The shaft is sealed with lip-type sealing rings and mounted on rolling bearings. The rotating unit is driven by an electric motor supplied through a frequency converter to maintain constant rotational speed.

The view of the test stand is presented in Fig. 3.

4 The Scope of Laboratory Testing

The tests were performed for the following parameter ranges:

-

volumetric flow rate (centrifugal flow)

$$Q = 0 {-} 0.01\;{\text{m}}^{3} / {\text{s}}$$ -

disc outside diameter d2 = 488 mm

-

disc rotational speed n = 1500 rpm, which is equal to angular velocity ω = 157.08 rad/s

For finned discs:

-

fin inside diameter dz1 = 144 mm

-

fin outside diameter, dz2 = 488 mm

-

number of fins z = 12

-

fin width b = 6, 8 and 10 mm.

In both cases (disc with and without fins), the gap between the disc and the casing was s = 4, 8 and 12 mm.

The disc shape and dimensions are shown in Fig. 1. The basic dimensions of the cavity where the finned disc is placed, as well as the method of feeding and carrying out water, are presented in Fig. 2.

5 The Measuring System

The diagram of the measuring system is shown in Fig. 4.

The rotating set rotational speed was measured using an electronic rotational speed meter.

The driving torque was measured with a torque meter.

The water flow rate was measured by means of the volumetric method, according to standard PN-EN ISO 8316:1999 Measurement of liquid volume flows in conduits. The volumetric method using dynamic method.

Moreover, pressure was measured in stuffing boxes.

The measuring instruments are listed in Table 1.

6 The Testing Programme

The tests were conducted in measuring series. Each measuring series was performed for the same disc (i.e., with the same disc dimensions and identical fins—if present) and with the same disc positioning in the cavity (i.e. with the same gap between the disc and the casing). The tests in a given measuring series were performed at a different volumetric flow rate.

The measuring series parameters are listed in Table 2.

In each measuring series, testing began at a low flow rate. When the parameters became stable, they were measured and the flow rate was raised to the maximum value. The final stage was to perform measurements for a declining flow rate.

7 Performance of Tests and Development of Results

During a steady-state motion, the power consumed to drive the test stand is needed not only to overcome the disc-liquid frictional resistance but also the forces related to the friction of the sealing, which, depending on the shaft sealing type, depends on the pressure value in stuffing boxes (Antoszewski 2012; Jia et al. 2014). This in turn varied depending on the flow rate. Measurements were made for the device operation with the shaft only (no disc). The power loss caused by the seal friction was determined depending on the pressure in stuffing boxes. The power values measured during the tests were corrected by the friction loss in the shaft sealing.

Because it is impossible to measure power for individual surfaces of the disc using experimental testing, the tests were made as comparative ones.

The aim of the testing was to determine the change in power consumption resulting from the presence of fins on the rotating disc surface compared to a disc with no fins.

7.1 The Unfinned Disc

The first stage of the testing was to measure power consumption when an unfinned disc was mounted in the casing (series 1–3).

The measurements were performed for three sizes of the gap between the disc surface and the casing wall s = 4, 8 and 12 mm.

Power consumption was calculated according to the following relation:

The dependence of power Pg on the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q for the unfinned disc rotating in water is characterized by a linear curve. An example dependence at gap s = 4 mm is illustrated in Fig. 5/series 1/.

Using the least-squares method, the dependence of power Pg on the volumetric flow rate Q was determined for each gap.

The dependence is of the following form:

The values of coefficients a0 and a1 together with the values of standard deviation σ in Eq. (2) Pg = f(Q) for the unfinned disc are given in Table 3.

Power Pg rises with a rise in the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q.

Analysing the obtained results, it can also be stated that at a constant flow rate Q, power Pg needed to keep the unfinned disc in motion depends only slightly on the size of gap s between the disc and the casing wall. In the tested range of gaps with s = 4 to 12 mm and flow rates Q = 0 to 10 dm3/s, the change did not exceed 4.5%.

The dependence of power Pg on the size of gap s for selected values of the volumetric flow rate Q for the unfinned disc is presented in Fig. 6.

7.2 Finned Discs

The next stage of the testing comprised measurements of finned discs (series 4–12).

Based on the results, it was found that more power was required for the rotational motion of finned discs compared to discs with no fins. The increase in consumed power P caused by the application of fins was calculated as the difference between power Pz consumed by a finned disc and power Pg consumed by an unfinned disc at the same size of gap s and the same flow rate Q.

Calculations of the measuring uncertainty were performed according to ISO/IEC Guide 98-3 (2008).

During the measurements of flow rate Q, average extended measuring uncertainty was UQ = 0.115 dm3/s at the confidence level of m = 0.95.

During the measurements of the increase in consumed power P, average extended measuring uncertainty was UP = 0.074 kW (confidence level of m = 0.95).

It was found that the dependence of power P on the centrifugal flow rate Q is also linear.

An example curve illustrating the dependence of power P on the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q for the finned disc (fin width b = 6 mm) at gap s = 12 mm (series 6) is presented in Fig. 7.

Using the least-squares method, the dependence of power P on the volumetric flow rate Q was determined for each disc and for each gap.

The dependence is of the following form:

The values of coefficients b0 and b1 together with the values of standard deviation σ of Eq. (4) P = f(Q) are given in Table 4.

In every case, the dependence P = f(Q) is an increasing function. A rise in the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q results in a higher consumption of power P.

7.3 Analysis of the Dependence of Power P on the Fin Width b

Figure 8 illustrates the dependence of power P on the different fin width (b = 6, 8, 10 mm) for a selected constant gap (s = 12 mm) (series 6, 9 and 12) and for selected values of the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q.

The curves for other values of gap s can be plotted using the coefficients listed in Table 4. The dependences are characterized by similar curves.

Analysing the obtained measurement results, it can be stated that power P rises with an increase in the fin width b.

7.4 Analysis of the Dependence of Power P on the Gap Width s

Figure 9 illustrates the dependence of power P on the size of gap s for a disc with a selected fin width (b = 6 mm) for selected values of the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q (series 4, 5 and 6).

The curves for other values of the fin width b can be plotted using the coefficients listed in Table 4. The dependences are characterized by similar curves.

Analysing the measurement results, it can be observed that the dependence of power P on the size of gap s for a finned disc is non-monotonic—it has a minimum. Fins on the disc may be used for different purposes: to reduce axial thrust, throw away impurities that might otherwise get to the sealing, lessen the pressure acting on the pump discharge-side stuffing box, etc. Regardless of the purpose of using finned discs, the testing results lead to one important conclusion: the size of gap s (disc positioning in the cavity) can be optimized so that the power loss should be as small as possible. In the case under analysis (shown in Fig. 9), the optimum position of the disc is for gap s = ~ 9 mm. This value was practically independent of the centrifugal flow rate Q, which means that the optimum position of the disc in the cavity does not depend on the centrifugal flow rate in the finned space.

8 Conclusions

Extensive laboratory tests were performed within the analysis presented herein to determine the change in power consumption resulting from using fins on a disc rotating in water. A centrifugal flow with a varied volumetric discharge rate occurred in the space on the disc finned-surface side. The tests were performed for different sizes of the gap between the fins and the casing and for fins with a different width. The tests were made at constant rotational speed.

Based on the obtained results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

fitting the disc with fins results in an increase in power consumption

-

the power consumption rises with a rise in the water centrifugal volumetric flow rate

-

the dependence of power consumption on the size of the gap between the fins and the casing wall is non-monotonic—it has a minimum; the size of the gap can be optimized to achieve the smallest possible power consumption

-

an increase in the fin width involves a rise in power consumption.

The determination of the rise in the consumption of power P resulting from fitting the disc with fins and depending on the centrifugal volumetric flow rate Q is an original outcome of the analysis presented in this paper. The dependence was defined for fins with different values of width b and for different sizes of gap s.

The detailed measurement results presented in this paper make it possible to calculate the rise in power consumption resulting from using fins on a disc rotating in water.

As for pumps, the results can also be used to design the axial thrust balancing system using balancing vanes and to optimize the system in terms of power consumption.

Abbreviations

- b :

-

Fin width, mm

- d 2 :

-

Disc outside diameter, mm

- d z1 :

-

Fin inside diameter, mm

- d z2 :

-

Fin outside diameter, mm

- K :

-

Accuracy class

- m :

-

Confidence level

- M :

-

Torque, Nm

- p :

-

Pressure, Pa

- P :

-

Difference in power between a disc with and without fins at the same flow rate, kW

- P g :

-

Power for an unfinned disc, kW

- P z :

-

Power for a finned disc, kW

- Q :

-

Volumetric flow rate (centrifugal flow), m3/s

- n :

-

Rotational speed, rpm

- s :

-

Gap between the disc/fins and the casing, mm

- t :

-

Temperature, °C

- U :

-

Extended measuring uncertainty

- z :

-

Number of fins

- Z :

-

Instrument range

- σ :

-

Standard deviation, kW

- ω :

-

Angular velocity, rad/s

- a 0 :

-

Coefficient of equation Pg = f(Q), kW

- a 1 :

-

Coefficient of equation Pg = f(Q), kW/(dm3/s)

- b 0 :

-

Coefficient of equation P = f(Q), kW

- b 1 :

-

Coefficient of equation P = f(Q), kW/(dm3/s)

References

Antoszewski B (2012) Mechanical seals with sliding surface texture—model fluid flow and some aspects of the laser forming of the texture. Procedia Eng 39:51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/jproeng.2012.07.007

Ayad AF, Abdalla HM, Abou El-Azm A (2016) Study of the effect of impeller side clearance on the centrifugal pump performance using CFD. In: ASME international mechanical engineering congress and exhibition IMECE2015, vol 7A, Article number: UNSP V07AT09A037

Bhatia A (2014) Theoretical analysis to calculate axial thrust in multistage centrifugal pumps. In: 12th European fluid machinery congress

Cao L, Zhang YY, Wang ZW, Xiao YX, Liu RX (2015) Effect of axial clearance on the efficiency of a shrouded centrifugal pump. J Fluids Eng 137(7):071101. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4029761

Cao L, Wang ZW, Xiao YX, Luo YY (2016) Numerical investigation of pressure fluctuation characteristics in a centrifugal pump with variable axial clearance. Int J Rotating Mach. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/930614

Daily J, Nece R (1960a) Chamber dimension effects on induced flow and frictional resistance of enclosed rotating disks. Trans ASME J Basic Eng 82(1):217–230

Daily J, Nece R (1960b) Roughness effects on frictional resistance in enclosed rotating disks. Trans ASME J Basic Eng 82(3):553–560

Daqiqshirazi M, Riasi A, Nourbakhsh A (2014) Numerical study of flow in side chambers of a centrifugal pump and its effect on disk friction loss. Int J Mech Prod Eng 2(3):23–27

Dong W, Chu W (2016a) Analysis of flow characteristics and disc friction loss in balance cavity of centrifugal pump impeller. Trans Chin Soc Agric Mach. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2016.04.005

Dong W, Chu W (2016b) Numerical analysis and validation of fluid pressure in the back chamber of centrifugal pump. J Mech Eng. https://doi.org/10.3901/jme.2016.04.165

Dykas S, Wilk A (2008) Determination of the flow characteristic of the high-rotational centrifugal pump by means of CFD methods. TASC Q 12(3–4):245–253. http://www.task.gda.pl/files/quart/TQ2008/03-04/tq312l-e.pdf

El-Naggar M (2013) A one-dimensional flow analysis for the prediction of centrifugal pump performance characteristics. Int J Rotating Mach. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/473512

Gantar M, Florjancic D, Sirok B (2002) Hydraulic axial thrust in multistage pumps—origins and solutions. J Fluids Eng 124(2):336–341. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1454110

Godbole V, Patil R, Gavade S (2012) Axial thrust in centrifugal pumps—experimental analysis. In: 15th international conference on experimental mechanics, ICEM, Paper Ref: 2977

Golovin VA, Kochevskii NN, Biryukov AI et al (1989) Calculation of prerotation in a rotating disk during radial flow. Sov Energy Technol 29–33

Gulich J (2014) Centrifugal pumps. Springer, Berlin

Hong F, Yuan J, Heng Y et al (2013) Numerical optimal design of impeller back pump-out vanes on axial thrust in centrifugal pumps. In: ASME 2013 fluids engineering division summer meeting. Paper No. FEDSM2013-16598. https://doi.org/10.1115/fedsm2013-16598

Iino T, Sato H, Miyashiro H (1980) Hydraulic axial thrust in multistage centrifugal pumps. J Fluids Eng 102(1):64–69. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3240626

ISO/IEC Guide 98-3 (2008) (JCGM/WG1/100) Urcentainty of measurement - Part 3: guide to expression of uncertainty in measurement (GUM:1995). International Organization for Standardisation ISO. www.iso.org. Accessed 3 Jan 2018

Jedral W (2001) Impeller pumps. PWN, Warszawa

Jia X, Guo F, Huang L et al (2014) Effects of the radial force on the static contact properties and sealing performance of a radial lip seal. Sci China Tech Sci 57:1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11431-014-5548-7

Kalinichenko P, Suprun A (2012) Effective modes of axial balancing of centrifugal pump rotor. Procedia Eng 39:111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/jproeng.2012.07.014

Karaskiewicz K (2013) Studies of flows in rotodynamic pumps for hydraulic forces prediction. Warsaw University Publishing House, Warsaw

Kim E, Palazzolo A (2016) Rotordynamic force prediction of a shrouded centrifugal pump impeller—part I: numerical analysis. J Vib Acoust 138(3):031014. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4032722

Lazarkiewicz S, Troskolanski A (1965) Impeller pumps. Pergamon Press, Oxford

Lefor D, Kowalski J, Herbers T, Mailach R (2015) Investigation of the potential for optimization of hydraulic axial thrust balancing methods in a centrifugal pump. In: 11th European conference on turbomachinery fluid dynamics and thermodynamics ETC11

Liu G, Du Q, Liu J et al (2016) Numerical investigation of radial inflow in the impeller rear cavity with and without baffle. Sci China Tech Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11431-015-5972-3

Lugova S, Matvieieva H, Rudenko A, Tvardokhleb I (2014) Determination of static and dynamic component of axial force in double suction centrifugal pump. Appl Mech Mater 630:13. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.630.13

Matsui J, Mugiyama T (2009) Effect of J-Groove on the axial thrust in centrifugal pump. In: 10th Asian international conference on fluid machinery

Nemdili A, Hellmann D (2007) Investigations on fluid friction of rotational disks with and without modified outlet sections in real centrifugal pump casings. Forsch Ingenieurwes 71(1):59–67

Owen J, Pincombe J (1980) Velocity measurements inside a rotating cylindrical cavity with a radial outflow of fluid. J Fluid Mech 99(1):111–127

Pfleiderer C (1961) Die Kreiselpumpen. Springer, Berlin

Piesche M (1989) Investigation of the flow in the impeller-side space of rotary pumps with superimposed throughflow for the determination of axial force and frictional torque. Acta Mech 78:175–189

Rohatgi U, Reshotko E (1974) Analysis of laminar flow between stationary and rotating disks with inflow. NASA Report No. CR-2356

Shimura T, Matsui J, Kawasaki S et al (2012) Internal flow and axial thrust balancing of a rocket pump. J Fluids Eng 134(4):41103. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4006470

Stepanoff A (1957) Centrifugal and axial flow pumps. Wiley, New York

Torabi R, Nourbakhsh SA (2016) The effect of viscosity on performance of a low specific speed centrifugal pump. Int J Rotating Mach. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3878357

Wang C, Shi WD, Zhang L (2013) Calculation formula optimisation and effect of ring clearance on axial force of multistage pump. Math Probl Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/749375

Wang Z, Gao B, Yang L, Du WQ (2016) Influence of clearance model on numerical simulation of centrifugal pump. Mater Sci Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/129/1/012020

Watanabe T, Furukawa H, Fujisawa S et al (2016) Effect of Axial Clearance on the Flow Structure around a Rotating Disk Enclosed in a Cylindrical Casing. J Flow Control Meas Vis 4:1–12. https://doi.org/10.4236/jfcmv.2016.41001

Wilk A (2003a) The analysis of the impeller discs friction losses in high speed impeller pumps. In: IX international conference on rotary fluid flow machines, Rzeszów, Poland, pp 307–213

Wilk A (2003b) Analysis of balancing the axial thrust with the relieving blades in rotational pumps for high rotational speed. J Transdiscipl Syst Sci 8:520–527

Wilk A (2008) Pressure distribution around pump impeller with radial blades. In: 6th IASME/WSEAS international conference on fluid mechanics and aerodynamics FMA. http://www.wseas.us/e-library/conferences/2008/rhodes/fma/fma33.pdf. Accessed 3 Jan 2018

Wilk A (2009) Laboratory investigations and theoretical analysis of axial thrust problem in high rotational speed pumps. WSEAS Trans Fluid Mech 4(1):1–13. http://www.wseas.us/e-library/transactions/fluid/2009/28-372.pdf. Accessed 3 Jan 2018

Wilk S, Wilk A (1996a) Tests of influence of impeller inlet sealing type on parameters of pump for hydraulic transport. WSI Opole Res Bull 43(218):293–296

Wilk A, Wilk S (1996b) Testing of the effect which relieving radial blades have on power loss and pressure distribution. Pumpentagung Pump Congress, Karlsruhe, Germany 1996, P/C2-4, pp 1–8

Wilk A, Wilk S (2001) Influence of relieving blades on pressure in stuffing-box of rotodynamic pump. In: 16th scientific conference problems of working machines development

Zhou L, Shi W, Li W et al (2013) Numerical and experimental study of axial force and hydraulic performance in a deep-well centrifugal pump with different impeller rear shroud radius. J Fluids Eng 135(10):104501. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4024894

Acknowledgements

This work has been developed thanks to the support from the statutory research fund of Silesian University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilk, A. Laboratory Measurements the Rise in Power Consumption Resulting from the Use of a Finned Rotating Disc at a Centrifugal Water Flow. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Mech Eng 43 (Suppl 1), 773–782 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40997-018-0194-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40997-018-0194-5