Abstract

A central and unique part of Sweden’s family policy programme is care leave that working parents can use when children are sick and cannot attend (pre)school. The gender-equal policy entails that parents may divide the leave as they see fit. However, mothers and fathers do not share care leave equally and care leave patterns may vary geographically. The aim of this paper is to examine the interaction between gendered care leave and geographical context using the theory of gender contracts. We ask how geographical variation in fathers’ share of care leave varies by scale, and how both individual factors and geographical determinants, representing local gender contracts, are associated with fathers’ share of care leave. Distinctive from previous work, we use geocoded full-population register data and individualized neighbourhoods at multiple scales in order to be able to better measure contextual effects on care leave use. We find substantial spatial variation in fathers’ share of care leave, with clustering depending on scale level. Using the nearest 200 fathers with young children, a factor analysis summarizes local gender contracts into three factors labelled as elite, marginalization and private sector. Results show that especially living in local gender contract areas identified as “marginalized” positively affects fathers’ share of care leave. Living in the most segregated neighbourhoods has substantial effects on fathers’ share of care leave, but overall, neighbourhood effects are moderate. A gender contract perspective shows negotiations resulting from locally clustered gendered norms and relative resources between partners influence who stays home with sick children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In Sweden, family policies aim at gender equality with mothers and fathers having the same rights to childcare, parental leave and other benefits of the family policy system no matter where one resides in the country. The policy targets individuals with both women and men taking economic and caring responsibility for their children. Universal and subsidized childcare is guaranteed in all municipalities, and nationally organized parental leave, paid out of employers’ contributions, are crucial parts of this policy. Another less studied but important part of the parental leave system is care leave that parents can use in case a child is sick and cannot attend preschool. The division of childcare is highly gendered, and tends to be associated to the gender division of others tasks and responsibility, and therefore the gender division of care leave is highly relevant. Who stays home with a sick child is, in contrast to decisions on parental leave, mainly based on short-term negotiations between the parents. In this paper we are interested in how such negotiations are associated with relative resources within the couple and to local gender norms, understood through the lens of gender contracts. The paper examines how both individual factors and geographically clustered gender contracts explain men’s uptake of care leave. Although the spatial articulation of gender relations has largely been neglected in earlier studies, there are several reasons to assume that gendered care leave varies by geographically clustered norms and contracts. Gender and space are co-constructed at the local level (Massey, 2005), and gender inequality has been found to vary across countries, spaces and between neighbourhoods (Duncan, 2000).

We use the concept of gender contract to examine gendered family policy use. Broadly defined, gender contracts are sets of agreements between genders. Yvonne Hirdman (1992, 1993) saw gender contracts as the outcomes of negotiations between men and women on issues like labour, family and power. Forsberg (1998) and Åström and Hirdman (1992) argue that gender contracts are formed and reconstructed by social interaction with others in shared context and places. At the household level, gender contracts represent the ways power is negotiated through work and home practices. At the local level, this then translates into a broader set of local gendered contracts. Geographical differences in gender contracts emerge from a combination of the overall structure of gender relations: the way these are arranged within local labour market conditions, in the demographic structure, and in historical and cultural traditions. Local gender norms are likely to differ by place, as gender equality is carried out at the couple and the local level.

One of the most obvious and most studied elements of the spatiality of gender is how different gender welfare regimes have led to distinct positions of men and women in different places (Duncan, 1995). In the 1990s, gender contracts were found to be linked to specific places (Duncan, 1994, 2000; Duncan & Pfau-Effinger, 2000). In most of these studies, gender contracts were operationalized using qualitative or mixed methods, while a few studies employed quantitative investigations. This paper builds on earlier work on local gender contracts in Sweden, namely Forsberg (1998, 2010) and Amcoff (2001), who identified different regional gender contracts. Using administrative data, both showed evidence of a north–south divide in gender contracts, with more equal municipalities in the north and more unequal areas in the south. Using data from the 1980s to 2001, Forsberg (2010) found five types of gender contracts, related to both local-historical conditions and national ideologies. A recently published study (Haandrikman et al. 2021) used recent register data and individualized neighbourhoods to identify local gender contracts: the metropolitan gender contract, the progressive gender contract, the suburban gender contract, the commuter gender contract and the traditional gender contract. Instead of a dominant gender contract in each region, the study evidenced considerable local variation. The study also established that geographical differences in how family policy is enacted and organized is likely to be shaped by gender contracts. The focus of the present paper lies instead on investigating the individual and spatial determinants of gendered care leave, where local gender contracts are used as spatial explanatory factors, using even more recent data.

Most work on local gender contracts consists of studies mapping gender contracts with a geographical unit of measurement that is problematic and outdated. Indeed, most studies used pre-defined areas such as municipalities and even larger regions as units of analysis. When analyses are conducted using such predefined areas, results may depend on how the borders of the neighbourhoods affect the aggregation of people within them, the so-called Modifiable Area Unit Problem (Openshaw, 1984). To overcome such issues, individualized neighbourhoods have become more common in recent literature: based on the individual’s nearest neighbours, each individual is appointed or collected into a neighbourhood (Andersson & Malmberg, 2018; Hennerdal & Nielsen, 2017; Wimark et al. 2019). An advantage to this method is that social interaction is captured better (Kwan, 2012; Nielsen & Hennerdal, 2017), and therefore suitable for this study as well as gender contracts are shaped in interaction with others in shared context and places. Using individualized neighbourhoods, recent studies have found that contextual or so-called neighbourhood effects on individual socio-economic outcomes are more substantial than studies using administrative areas (Andersson & Malmberg, 2015, 2018; Malmberg & Andersson, 2015; Malmberg et al. 2014; Östh et al. 2013; Wimark et al. 2019). Given that we do not know at which scale gender contracts are constructed, a multiscalar methodology enables the size of the neighbourhood to vary, which is preferred over uniscalar studies (Fisher et al. 2004; Fowler, 2016; Hennerdal & Nielsen, 2017). This helps us to understand neighbourhood effects better, i.e. how the neighbourhood affects individual behaviour (Clark et al. 2015).

In this paper we focus on care leave, which is an important pillar of the Swedish parental leave system. Care leave, officially called “temporary parental benefit to care for a sick child” entails that working parents can stay at home when their child, up to the age of 12, is sick for a maximum of 120 days per child per year. Parents receive about 80% of their regular income when taking care leave. This type of leave is more equally shared between mothers and fathers than parental leave for young children but gender differences remain: in 2017, the share of care leave days taken by men was 38% vs 28% of parental leave days taken by men, with very little change over time in men’s uptake of care leave (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2018). Leave to care for sick children is an excellent policy to understand the gendered division of care and household tasks (Eriksson & Nermo, 2010).

Our overarching aim is to examine the interaction between family policy and geographical context by applying the concept of gender contracts and employing individualized neighbourhoods. In order to address our aim, we ask two questions. First, what does the contemporary geographical variation in fathers’ share of care leave look like at different scales? Second, how is fathers’ share of care leave associated with individual as well as geographical determinants, which represent different indicators of local gender contracts? We contribute to the literature in five ways. First, we will add to the literature on family policy the role that contextual effects may play in gendered decisions on care leave. Second, we use micro-level register data on the full population of Sweden instead of regional indicators or regional case studies as previous studies have done (Amcoff, 2001; Forsberg, 1998, 2010). Third, we use indicators at both the individual and the neighbourhood level in order to separate individual from spatial effects. Fourth, we use an individualized measure of neighbourhood that is exceptionally suitable to examine contextual effects on leave uptake as it comes close to what a neighbourhood is and how it may affect individual behaviour. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to combine contextual effects and gender contracts. Fifth, our methodology is an innovative multiscalar approach to acknowledge that local patterns of family policy uptake are different depending on the scale level.

The paper continues with a review of Swedish family policy with a focus on care leave use, particularly at the local level. Following, we introduce the concept of gender contract before we review how it has been operationalised and what new opportunities data development has given us for using the concept. We use register data on the complete Swedish population to study individual and local variation in family policy use, which is described in the data and methods section. In the results section we present patterns of local variation in men’s share of care leave, including its determinants on the individual and the local level. We conclude with a discussion of key learnings and suggestions for future studies on individual and geographical variations in family policy use.

2 Swedish Family Policy at the Local Level

Sweden’s family policy has developed on a path towards achieving gender equality from as early as the 1960s. With the established male breadwinner model transitioning to the earner-carer model, the goal of sharing childcare between parents became explicit (Ferrarini & Duvander, 2010). The main pillars grounding the system were the universal introduction of individual taxation, availability of parental leave and public, high quality and affordable childcare. For married women (often mothers), the introduction of individual taxation for spouses in 1971 made it economically profitable to work (Gustafsson, 1992), while parental leave and available childcare enabled both parents to be employed. Initially these reforms were aimed at getting women into the workforce but predominantly emerging in the 1980s and 1990s, the goal shifted to encouraging men to participate in childcare.

With the introduction of Swedish parental leave policy in 1974, parents could decide how to share their leave designated to a child. Despite a slow start, fathers’ parental leave started to increase when months were earmarked for each parent in 1995 (Duvander & Johansson, 2012). As of 2020, parental leave is 16 months long, with three earmarked months for each parent. If these designated months are not taken, the benefit is forfeited. Fathers today take almost a third of all leave days.

Care leave is a central part of Swedish family policy and part of the parental leave system that makes the combination of work and family possible for many. When children have common illnesses, working parents (or other caregivers) are entitled to stay at home for a maximum of 120 days per child per year, from when the child is 8 months until it turns 12 years old.Footnote 1 Benefits are about 80% of the individual wage with a ceiling for high earners. However, the ceiling is lagging behind wage development; today over half of all men (and over a third of all women) have an income above the ceiling (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2020). The leave can be used by both parents and it can also be transferred to a close adult, such as a grandparent or an aunt or uncle. However, the transferring of days is very uncommon and as most women and men work, and stay in the labour market until high ages, familial childcare support is uncommon.

There is a substantial literature on the gendered uptake of parental leave, but fewer studies focus on the gendered division of care leave. Most parents do not take many care leave days, but when they do, gender differences appear (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2019). Care leave days are more often taken by the partner with the lower income, which tends to be the woman. Fathers’ share of care leave increases as mothers’ relative wage decreases, indicating that bargaining power based on differences in resources between partners are decisive when it comes to decisions on who stays home when a child falls ill (Boye, 2015b). Boye (2015a) and Stafford and Sundström (1996) found that uptake of care leave was negatively correlated with wage development, especially for men. One interpretation is that for women, it is generally expected that they take leave periods, whereas longer leave is seen to have more negative consequences for men in the workplace, as leave uptake is less common and could be associated with lower engagement. Amilon (2007) found that care leave is shared more equally when the woman is higher educated than the man, and this is less so when the woman is lower educated. Occupation and level of flexibility at work also play a role in who takes the care leave days (Boye, 2015b). In the public sector, where women are overrepresented, it may be more accepted that employees often take care leave, not least because it is more common but also perhaps because the organizations are less often based on economic profit. In addition, those with higher paid jobs, which more often are men who may have more flexible schedules, may opt for different strategies when their children are sick. For example, instead of officially taking care leave, a flexible work situation may make it possible to work from home while caring for a sick child. Gender norms about fatherhood, motherhood and gender equality influence the division of care leave between partners (Alsarve et al. 2019; Eriksson, 2011; Ichino et al. 2019).

Geographical differences in parental leave use are likely related to local labour market conditions and population composition, and we may assume these also affect the geographical variation in care leave. Regarding parental leave, fathers in metropolitan areas use more and fathers with immigrant backgrounds use less (Almqvist et al. 2010; Ma et al. 2019; Mussino, 2018) and it is likely that care leave follows similar patterns. The gender division of care leave is most equal in urban areas, and there are large differences between Swedish municipalities (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2019).

Until 2005, parental leave was administered by local social insurance agencies, overseen by national regulations as implemented by the National Social Insurance Board. Local agencies were encouraged to increase gender equal parental leave, but differed in their implementation. Many agencies organized information and encouragement campaigns directed towards increasing fathers’ parental leave with varying success (Klinth, 2002). It may be such campaigns have led to regional differences in fathers’ uptake of parental leave. Since the centralisation of the Swedish Social Insurance Agency in 2005, implementation throughout the country has become more uniform with regional variation in parental leave uptake diminishing (The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate, 2011).

In order to highlight how local variation in gender (in)equality and negotiations contribute to gendered patterns of care leave use, we will now turn to gender contract theory, which will provide us with links between individual decisions and local outcomes.

3 Using Gender Contracts to Explore Family Policy in Practice

Gender contracts are broadly defined as generalized social agreements on gender roles. As a theoretical concept, gender contracts provide a means to examine the ways in which power negotiations over work and home practices, in households, translate into a broader set of gendered societal ‘contracts’. Gender contracts include both the formal and informal arrangements of daily lives ranging from work relations to domestic divisions of labour (Forsberg et al. 2000: 42 based on Åström & Hirdman, 1992). The concept gender contract derives from the historian Yvonne Hirdman’s (1992, 1993) work examining how gender systems, divided into spheres of female and male, results in patterns of negotiated behaviour, or contracts, within households. While earlier studies of gender contract theory places women as structurally or systematically subordinate to men, this approach has been nuanced especially as the theory developed the local gender contract perspective. Individuals do have agency and are active participants in the construction and maintenance of gender contracts. Men and women negotiate gender norms in daily life, such as care leave, which results in a set of shared gender contracts but negotiations should be understood as enacted by differently positioned actors. However, the context of gender contracts may change, for example, from a policy intervention, resulting in local contracts changing across time and space.

Gender contract theory emerged within the context of the Scandinavian universalistic welfare state where governments had committed itself to gender equality and women-friendly reforms and initiatives (Duncan, 1995). Studies of gender contract outside of the Nordic context have been done in Africa (Adu-Gyamfi et al. 2019; Caretta, 2015; Caretta & Börjeson, 2015; Kalabamu, 2005), in Asia (Goldstein-Gidon, 2019; Golovina, 2018; Lindeborg, 2012), elsewhere in Europe (Kashina & Tkach, 2020) and in multi-sited research (Webster and Caretta, 2016). While applicable in all settings, gender contract theory, is especially useful in contexts with strong institutional welfare systems and in particular to studying changes in gender norms during times of large scale policy reforms (Leira, 2002). Due to gender contracts’ emphasis on linking policy with social reproduction it is a useful lens for understanding changes to gender relations, for example the implementation of a new policy. Unlike other approaches to understanding gender relations, the weight placed on structures emphasizes individual agency within institutional change. Additionally, gender contract theory highlights the ways gender negotiations are produced, rather than imposed on women, with negotiations being opportunities to improve their own position within norms and expectations (Kalabamu, 2005). Further, with the theoretical advancement to conceptualize the local gender contract, geography is explicitly used to understand gendered relations (Forsberg, 2001). By directly connecting geography with gender relations, local gender contract offers opportunities to bring spatial analysis to the fore, which other gendered approaches do not explicitly provide.

Forsberg (2001) showed that gender contracts are shaped by local politics, working life and everyday life especially with resources and local culture shaping gender contracts, while acknowledging the role of individual agency in these processes. In terms of childcare, local gendered norms may influence who stays at home with a sick child and overtime establish norms which vary spatially. Bargaining or negotiating may also be seen in gender contracts at the couple level, but it should not be understood necessarily as a neutral or equal process or focused on a specific issue, rather gender contract offers a means to explore ongoing shifts in bargaining positions and thus changes to gender contracts (Adu-Gyamfi et al. 2019). According to Alsarve et al. (2019), Swedish parents act in a context where gendered norms about motherhood and fatherhood coexist with vigorous institutional norms about gender equality. Finally, negotiations at the individual level result in different outcomes for the couple: who has the best bargaining position based on relative income or other resources? The relative resources perspective entails that the likelihood of sharing (parental) leave increases with the woman’s resources relative to the man’s, supported by several Swedish and European studies (e.g. Boye, 2015b; Geisler & Kreyenfeld, 2011; Naz, 2010; Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2013). Care leave represents a site of negotiation that is provided by the state but negotiated by individual couples who are situated in specific contexts shaped by local gender contracts.

Specific gender contracts are situated in time and place and develop from a process of conflict, negotiation and renegotiation with newly arising conflicts/ negotiations resulting in changes over longer time periods (Forsberg, 2010). Gender contracts being shaped by spaces and places has been examined in a number of studies in Sweden, mostly using qualitative or mixed methods, and often based in rural areas (Amcoff, 2001; Forsberg, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2010; Forsberg & Lindgren, 2015; Forsberg & Stenbacka, 2017; Forsberg et al. 2006; Gil Solá, 2016; Haandrikman et al. 2021; Hedfeldt, 2008; Stenbacka et al. 2018; Webster & Caretta, 2016). Forsberg (1998, 2010) and Amcoff (2001) used a range of regional statistical indicators to operationalize gender contracts. Using census data from 1990, Forsberg (1998) found substantial regional variation in gender contracts; principally a north–south divide was observed with more equal municipalities in the north and more unequal municipalities in the south. A follow-up study by Forsberg (2010) based on the analysis by Amcoff (2001) employed data from the 1980s to 2001 for municipalities and local insurance agency areas, suggesting the existence of five gender contracts: the modernistic, the traditional, the middle non-traditional, the individual non-traditional, and the “Norrland contract”. Most gender contracts were are geographically dispersed. The more recent Haandrikman et al. (2021) study used register data for the year 2012 as well as individualized neighbourhoods to classify local gender contracts, and five contracts were identified: the metropolitan gender contract, the progressive gender contract, the suburban gender contract, the commuter gender contract and the traditional gender contract.

Previously the view has been that in each region, one gender contract is dominant (Forsberg, 2010). More recent studies have challenged this view. For a rural area in Norway, Grimsrud (2011) showed that different gender contracts may occur in the same area, and that they may change because of migration. Gerrard (2017) found that traditional gender contracts in Norway’s High North changed over time due to increasing gendered mobility and changes within the fishing industry. In Sweden, Forsberg and Lindgren (2015) discerned geographical variation in gender contracts within a rural area, and Forsberg and Stenbacka (2013; 2017) identified different transformations in local gender contracts over time. Haandrikman et al. (2021) established substantial local variation in gender contracts. This implies that gender contracts are by no means static; they are constantly changing and responding to societal shifts.

These studies point to the importance of understanding the interaction between spatial context and gender contracts and highlight the need for further and more detailed analysis at spatial levels where gender is routinely negotiated, for example at the local or neighbourhood level, as gender contracts are formed and reconstructed by social interaction with others in shared context and places (Åström & Hirdman, 1992; Forsberg, 1998). In the Swedish context, fathers have the same rights to childcare policies as mothers and are expected to actively use policies by the state; this implies that negotiations, at least from a policy perspective, should be relatively equal. By examining local variation in fathers’ uptake of care leave we can shed light on the geographical outcomes of these gendered negotiations.

Our hypotheses can be summarized as follows:

Hypothesis 1

Gendered care leave varies by geographical location and by scale level.

Previous research has shown that relative resources within a couple are associated with gendered care leave. In our study, we will examine whether in addition to these individual level effects, local clusters of gender contracts also play a role in fathers’ care leave uptake. These geographically clustered gender contracts may be determined by a combination of factors, such as the share of high educated and high earning men and women and the level of unemployment in the neighbourhood, and the share of residents working in the public sector.

Hypothesis 2

In addition to individual determinants, we expect fathers’ share of care leave to be higher in areas where women and men have more favourable labour market positions, and in areas with high shares working in the public sector.

4 Data and Methods

We used geocoded register data on the entire Swedish population from 2015, containing a wide range of demographic and socio-economic variables. The excellent geographic attributes enable a spatial study with higher geographical detail, as we have geographical coordinates for place of residence for each individual, with a resolution of 250 by 250 m squares for urban areas and 1000 by 1000 m squares for rural areas. Other datasets used include the register on the total population (RTB), the longitudinal integration database for studies on health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and the Multigenerational register (FlerGen). Information from the different registers can be linked using anonymized identification numbers, and based on a family identification number, individuals can be linked to their partners and children. Partners are defined as two people living in the same property and either being married or living together with common children. Geographical coordinates are based on individuals’ registered properties.

As mentioned, there is a need for better measurement of the area that allows for local outcomes of gender inequality, and in recent decades, geographically coded data that enable such measurement have become increasingly available to researchers. One solution to address the complicated relationship between spatial context and gendered family policy uptake is to use a multiscalar approach and individualized neighbourhoods. A multiscalar methodology allows the researcher to examine several scale levels at the same time, and to assess which level is most appropriate, which is useful for ascertaining the most suitable scale for gendered family policy use and gender contracts. An increasing number of studies encourage such approaches over uniscalar studies (Fisher et al. 2004; Hennerdal & Nielsen, 2017). Using individualized neighbourhoods means that every individual (a resident) in a given area is assigned the same number of neighbours, and that the geographical size of the neighbourhood varies based on population density. By defining neighbourhoods in this way, we gain theoretical improvement because social interaction between individuals and policy structures at the regional and national level are better captured (Kwan, 2012; Nielsen & Hennerdal, 2017). Individualized neighbourhoods were constructed with the software EquiPop.Footnote 2

Our measure of gendered care leave is measured as men’s share of the couple’s uptake of days of care leave. Officially, this leave is called “temporary parental benefits” but colloquially it is called VAB (Vård av Barn, meaning taking care of children). Temporary parental benefits also include 10 days that can be taken in connection with the birth of a child by the non-pregnant parent. As most fathers take these 10 days, they are not a good indicator of gendered family policy use. We therefore withdrew 10 days for those men who became fathers in 2015. As most care leave days are taken out for pre-primary school children, we only consider parents with children aged 0 to 6 years. The dependent variable used in the analyses measures the share of care leave days used by fathers, divided by the days used by mothers and fathers with children aged 0–6 taking care leave.

Our research strategy consists of two parts. First, we map fathers’ share of care leave on different scales in order to investigate how gendered family leave uptake is manifested at different local and regional scales. Second, we model fathers’ share of care leave at one scale level in several regression analyses, using a set of individual and neighbourhood determinants. The variables at the individual level represent factors that have been found to be associated with gendered care leave, related to the educational, employment and income advantage of one partner versus the other partner, as well as a variable measuring native advantage and one comparing the dynamics in a couple based on working in the private sector or not. Third, a range of human capital, socioeconomic and demographic variables that represent local variation in gender contracts was included on the neighbourhood level.

4.1 Individual-Level Variables

At the individual level, we included five variables that capture relative resources related to gendered negotiations in the household, that are based on previous studies on the determinants of care leave. Each variable is measured at individual level, comparing the characteristic of the father of young children compared to those of his female partner. First, we compare the educational levels of both partners. This was measured as the highest completed level of education, categorized as primary, secondary or tertiary education. The variable included in the analyses indicates whether (1) the man is higher educated, (2) the woman is higher educated; (3) both are higher educated; or (4) both are lower educated (lower than tertiary). Second, employment advantage indicates whether (1) the man is employed while the woman is not employed; (2) the woman is employed while the man is not employed; or (3) both are employed. As we are interested in advantages based on relative resources, we excluded those couples where both partners were unemployed. Employment is based on the Statistics Sweden measure of being employed in November. Third, native advantage is operationalized as (1) the man is Swedish-born, the woman foreign born; (2) the woman is Swedish-born, the man is foreign born; (3) both are Swedish-born; or (4) both are foreign born.

Fourth, income advantage compares income levels between partners, based on income from employment and self-employment. For both men and women, we used income quartiles, specifying whether an individual has income in the lowest quartile, has a midrange income (second or third quartile) or a high income (fourth quartile). Income advantage is measured as (1) the man having high income, the woman midrange; (2) the man having high income, the woman low income; (3) the man having midrange income, the woman low; (4) the woman having high income, the man midrange; (5) the woman having high income, the man low; (6) the woman having midrange income, the man low; (7) both having a low income; (8) both having a midrange income; (9) both having a high income. Finally, private sector advantage compares the man and woman in terms of their workplace, where we are interested in who works in the private sector. The definition of private sector is based on the sector code assigned to each person that is employed or has their own business. Individuals who work in companies that are privately owned were identified. We classified private sector advantage as (1) man working in private sector, not the woman; (2) woman working in private sector, not the man; (3) both working in the private sector; or (4) both not working in the private sector.

4.2 Neighbourhood-Level Variables

The selection of neighbourhood variables was chosen to represent factors constituting gender contracts at different levels and are based on findings from previous studies measuring gender contracts in a quantitative way (Amcoff, 2001; Forsberg, 1998, 2010; Haandrikman et al. 2021), which in turn were based on Walby’s (1990, 1994) dimensions of differentiated patriarchy. We included ten indicators that represent the level of human capital among neighbours, labour market participation among neighbours, and neighbours’ demographic characteristics. Table 1 lists the indicators that are described in detail below.

Five indicators for human capital in the neighbourhood were included. First, we measured the share of women with higher education among the nearest female neighbours aged 25–65. Higher education is operationalized as any completed level higher than secondary education. The same indicator is included for men. We also included an indicator of high earners for women, measuring the share of women earning at least 10 times the “price base amount” (prisbasbelopp in Swedish) among women earning some income in the neighbourhood. The price base amount is an amount based on the consumer price index and is adjusted annually by the government. For the year 2015, it was 44,500 SEK. Temporary parental benefits are paid as 80% of income, with a ceiling of 7.5 price base amounts. If a person has a higher income, that person would loose relatively more income. Income is measured as taxable earned income, summed as the gross salary and income from active businesses, reported to the Swedish tax office by employers. The indicator measures the share of women earning at least 10 price base amounts among women aged 25–65 who earn some income, in the neighbourhood. In addition, to control for average neighbourhood income, we included a variable measuring average taxable earned income among the nearest neighbours.Footnote 3 Finally, we include a measure of women’s average income divided by men’s average income among the nearest neighbours.

Four indicators regarding the labour market dimension were included. First, the share of unemployed women (men) among the nearest female (male) neighbours aged 25–65 were included. Unemployment was measured as not being employed according to the national tax agency. Second, two indicators consider the share of parents working for private companies. For the definition of private sector, see above. We measured two indicators, one for mothers and one for fathers, with parents defined as those individuals living as married or cohabiting with shared children, or single parents who have children in their household. The indicators measure the share of employed mothers and fathers respectively that work in the private sector, among the nearest neighbours.

A final indicator examines the share of mothers not living with the father of their youngest child. Using the multigenerational database, parents registered in Sweden are linked to their children. Using the IDs of children, fathers were compared to current partners of mothers, defined either as husbands or as male partners with whom these women share children. Only families with children aged 0–18 were considered. The indicator measures the share of mothers not living with the father of their youngest child divided by mothers with children living at home, among the nearest neighbours. A variable measuring population density in each grid is included as well.

These variables capture variation in compositional characteristics between neighbourhoods, for instance the share of high earners and the share of unemployed men. Such variables are indicators of factors that shape the local gender contract at different levels. So if women’s income compared to men’s is relatively high in a neighbourhood, we may expect that men’s share of care leave is higher based on previous studies. Likewise, if the share of employed male neighbours that works in the private sector is high, one would expect a lower share of fathers taking care leave. From these examples, we will examine whether negotiations which produce gender contracts are situated within a variety of factors.

5 Results

5.1 Geographical Variation in Fathers’ Uptake of Care Leave

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics on fathers’ uptake of care leave in 2015. Fathers on average take 43% of couples’ care leave days to take care of sick children among those with children aged 0–6. This share is somewhat higher than the official statistics by the Social Insurance Agency, where children age 0–11 are included, and where, besides parents, for instance relatives taking care of children are included. The 2018 report found that 40% of care leave benefits were paid out to men in 2017, with women using about nine days and men about seven annually (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, 2018).

Table 2 shows that the average share of fathers taking up care leave among couples in neighbourhoods comprising the 200 nearest fathers with young children is 41%.Footnote 4 There are slightly over 100,000 populated individualized neighbourhoods. In the 20% neighbourhoods with the lowest levels of fathers’ uptake of care leave, the leave is less than 32%, while in the neighbourhoods with the highest share; it is between 50 and 100%.

Defining neighbourhoods from individuals based on fixed population count means that the geographical area to reach the fixed count varies by population density. Table 2 shows that the average distance to reach the 200 nearest neighbours is almost 2 kms, but distances are, of course, shorter in densely populated areas and larger in sparsely populated areas. This means some neighbourhoods are larger compared to conventional ways to define neighbourhoods (see also Andersson et al. 2018). As the perception of who your neighbours are also varies by population density, this definition of neighbourhood can be argued to be better than that of administrative neighbourhoods (see for instance Wimark et al. 2019), though geography makes a difference in how far away these neighbours are located.

Figure 1 displays five maps of the share of fathers taking up care leave among their nearest neighbours. The k-levels indicate the number of nearest neighbours included: the first map shows the share of fathers taking up care leave among the 50 nearest fathers with young children, the second map shows the same for the nearest 200 fathers of young children, and so on, with the last map showing the share of fathers taking up leave among the 25,200 nearest fathers with young children. The colour coding indicates quintiles of care leave use; the intervals of fathers’ share of care leave for each colour therefore differs between the different maps. Results are shown as average shares for each grid cell, which are 250*250 m squares in urban areas and 1000*1000 m squares in rural areas.

Share of fathers’ uptake of care leave for different k-levels. Note: Map classifications are based on quantile distributions. The Global Moran’s I statistics for spatial autocorrelation is 0.974 for k = 25,200; 0.956 for k = 6400, 0.876 for k = 1600; 0.609 for k = 200 and 0.358 for k = 50, all significant at the level of p = 0.001

First, we can see that there is large local geographical variation in men’s share of care leave. There are many areas where similar values of fathers’ share of care leave is clustered. Second, these maps highlight the importance of scale in understanding local variation in care leave uptake. Depending on the choice of scale level, the geographical pattern of leave uptake looks substantially different. At the lower scale levels, examining care leave uptake among the 50 nearest fathers with young children, there is considerable local variation in fathers’ share of care leave. The level of clustering is reflected in the increasing Global Moran’s I with increasing scale level. If we zoom out and include several thousands of neighbours in the definition of the neighbourhood, there are larger clusters of homogenous patterns of fathers’ care leave shares. In the south and the western part of the country, as well as in remote areas, there are larger areas of relatively low shares for fathers’ care leave. In the metropolitan areas of Stockholm and Gothenburg there are clusters of fathers with relatively high shares of leave use. The patterns for fathers’ share of care leave days show large clustering as of k = 1600. These maps indicate that contextual effects are important for negotiations between partners in who takes the care leave: being surrounded by fathers taking leave to care for their sick children has contagious effects.

Figure 2a–c zoom into three specific areas in Sweden to show localized patterns of fathers’ share of care leave uptake. The maps are all on the scale of k = 200, so including relatively small numbers of nearby fathers with children in the same age category. At these lower scale levels, there is much variation in men’s care leave, however patterns can still be discerned. Figure 2a shows local variation in central Stockholm. Areas with substantially higher shares of care leave for fathers (more than 50%) include Årsta, Bagarmossen and parts of Södermalm, but they are often located next to areas with much lower uptake such as Alvik and Älvsjö.

a–c Share of fathers’ uptake of care leave among the 200 nearest fathers with children aged 0–6. a Central Stockholm area. b Area around Jönköping and lake Vättern in central Sweden. c City of Kiruna in upper North of Sweden. Note Map classifications are based on quantile distributions, see Fig. 1, k = 200

The area around lake Vättern (Fig. 2b), that may be seen as being part of the Bible Belt, characterized by relatively high church attendance, a high share of voters for the Christian democrat party and a high share of small firms and self-employment (Haandrikman, 2019), is characterized by higher shares of fathers’ care leave in built up areas, but lower shares in rural areas. Kiruna, in the far north of the country, is a small town in an otherwise sparsely populated area, as seen in Fig. 2c. State-owned mining plays an important role for employment in the area and the public sector is the main employer. In central Kiruna, fathers’ share of care leave is low, and especially so in the parts of the town called Norrmalm and Östermalm.

In order to study whether these locally clustered patterns are the result of local gender contracts, we need to choose one neighbourhood scale for a regression analysis. The motivation for choosing the most appropriate k-level is based on the level of clustering of fathers’ uptake of care leave in combination with a consideration of a scale level that best reflects how local gender contracts affect fathers’ share of care leave. Referring back to the construction of gender contracts, we need to think about how gendered norms, labour market structure and relative resources influence negotiations between men and women on who takes the leave and stays at home with the sick child. We consider it likely that a relatively small neighbourhood scale is appropriate when examining contextual effects on taking care leave; as seeing or meeting other fathers with young children in the local neighbourhood and talking to them at preschool may be more important than larger scale influences. A visual analysis of the maps in Fig. 1 together with the measures for spatial autocorrelation indicate that a k-level of 50 is not likely to properly reflect local gender norms on fathers leave uptake. Very high scale levels tend to obscure more interesting local patterns, and therefore we consider a scale level of the nearest 200 fathers with young children to be most appropriate and this will be used for the regression analyses. Recall from Table 1 that the average distance to reach the nearest 200 fathers with young children is about 2 kms. We acknowledge that this choice is still subjective and welcome empirical studies at other levels to accumulate a knowledge base that facilitates the choice of neighbourhood level for various research questions. In the regression analyses, we include sensitivity analyses for different k-levels to test the robustness of our models.

5.2 Explaining Fathers’ Uptake of Care Leave Using Individual and Neighbourhood-Level Determinants

This part of the analysis aims to explain fathers’ share of care leave using both individual-level and neighbourhood-level determinants. Table 3 shows descriptive statistics on individual variables, while Table 4 provides these on the neighbourhood variables.

A correlation analysis showed that several correlations between the 10 neighbourhood-level indicators were too high to be included in a regular multivariate analysis. Therefore, factor analysis was used to reduce the number of neighbourhood variables into a smaller number of factor variables that still covers the contents of the original variables.

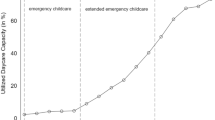

The factor analysis resulted in three factors, explaining 63% of the total variance in the population of fathers with young children.Footnote 5 Table 5 presents the factor loadings for the three factors. Most variables load highly on the first factor. High loadings on factor 1 seem to relate to different aspects of very high human capital among both men and women in the neighbourhood, especially high earning women and higher educated women and men. We label this factor elite. In factor 2, variables have especially high loadings on neighbouring men’s and women’s unemployment, low average neighbourhood income, and high loadings on mothers not living with the fathers of their youngest child in the neighbourhood. We label this marginalisation. Finally, variables loading high on the third factor represent neighbourhoods with high shares of both mothers and fathers working in the private sector, therefore labelled private sector.

Figure 3 shows a percentile plot for the three factors, represented by the three lines. The graph shows the proportion of individuals living in neighbourhoods characterized by different factor values. The graph shows, for instance, that 80% of fathers with young children lived in neighbourhoods that had factor scores that were equal to or lower than 0.63 for elite, 0.63 for marginalisation and 0.70 for private sector; or that 20% of fathers lived in areas with factor values higher than these values. Similarly, 10% of fathers with young children lived in areas with factor values for elite higher than 1.34. The distribution shows that especially those living in the top 20% areas with the lowest and highest factor values have the most deviating pattern. For instance, the bottom 10% of neighbourhoods with the lowest factor values for private sector consists of areas with very high shares of employees in the public sector. Likewise, the 10% most elite neighbourhoods are areas with extremely high average income, very large shares of women earning high incomes and very high educated neighbours.

An OLS regression was then performed with fathers’ share of care leave as the dependent variable. Five individual variables reflecting the relative resources of both partners were included as independent variables in Model 1. Model 2 includes neighbourhood-level variables reflecting local gender contracts, which are the three factors that resulted from the factor analysis. These variables consist of factor scores for each individualized neighbourhood on the three factors degree of elite, marginalisation and private sector. Table 6 shows the regression results.

The results show that both individual and neighbourhood-level variables are important in explaining fathers’ uptake of care leave. About 22% of the variance is explained by the two models, with the neighbourhood model explaining a significant part of the variance,Footnote 6 though neighbourhood effects are not very large.

Starting with the association between individual-level variables and fathers’ uptake of care leave, we can see that all couple-level variables reflecting different types of relative resources are related to fathers’ uptake of care leave. Using predicted margins, we can compare the effects of the different indicators on the share of fathers taking care leave in the couple. Figure 4 shows these margins for income advantage. Men with the highest rates of care leave are those fathers earning a midrange income while their partner has a low income (predicted probability of 76%), and fathers with a high income with partners in the lowest income quartile (67%), and those where both have low incomes (71%). On the other hand, care leave is much lower, 27% as opposed to the average of 43%, when fathers earn a very high income while their partners earn a midrange income, or when both earn high incomes. These findings are partly in line with Boye (2015b) who found that fathers’ use of care leave increases with decreasing women’s wages. However, this does not apply to top income fathers with midrange earning partners. In such cases, the income loss for men will be substantial, while their partners still make a decent income when taking leave.

Other findings from the models in Table 6 show that fathers’ share of care leave is highest for couples where both partners are higher educated. This is a new insight, adding to Amilon’s (2007) findings that care leave is shared more equally between partners when the woman is higher educated. Another addition is that we find that Swedish-born men with foreign-born partners tend to take more leave compared to men in couples where both partners are from Sweden or both are migrants. When it is the man who is foreign-born in the couple, the man is less likely to take up a high share of care leave. These divisions of care leave between parents of different background are likely related to the positions they have on the labour market where foreign-born individuals are more likely to suffer of temporary absences from their jobs as their positions are less secure. These are effects net of educational, income and employment characteristics. Finally, if a man does not work in the private sector but his partner does, he is more likely to take up care leave, while care leave uptake is much lower when it is the other way around.

Model 2 shows the results for fathers’ share of care leave when including neighbourhood effects, or in other words, the associations between local gender contracts and fathers’ share of care leave. Living in a neighbourhood with a high score on elite is associated with an increase in fathers’ share of care leave. Surprisingly, also living in neighbourhoods that have higher scores on marginalization is associated to higher levels of care leave. Fathers living in areas with high shares of neighbours working in the private sector are less likely to take up care leave, net of couple effects of working in the private sector. All neighbourhood factors are significant, but their effects seem moderate based on the regression results. For a one standard deviation increase in the factor score on marginalization (1.142), men’s share of care leave increases with 0.453. Similarly, an increase of one standard deviation on the factor score elite (0.470), men’s share of care leave increases with 0.134; and a standard deviation increase in the private sector factor score (1.012) is associated with a decrease of 0.189 in care leave. Figure 5 shows how living in a neighbourhood with different neighbourhood scores on the three factors is associated to fathers’ predicted probability of care leave. The x-axis shows neighbourhood percentiles, going from the least segregated neighbourhood on the left to the most segregated neighbourhood on the right, in terms of elite, marginalization and private sector. A neighbourhood at the 50th percentile may be seen as the average neighbourhood. The predictive margins confirm that the contextual effects on fathers’ share of care leave are quite modest. The slopes of the three lines indicate that the effects of marginalization is far greater than that of score on elite and private sector. The difference between living in the 10th least elite neighbourhood and the 99th most elite neighbourhood translates into an increase of a mere 0.6 percentage points in fathers’ share of care leave. The effects of the degree of neighbourhood marginalization are slightly higher, with a predicted probability of fathers’ share of care leave of 43.1 for an average neighbourhood and a probability of 44.7 for the 99th percentile, i.e. the 1% most marginalized neighbourhood of Sweden. It is also interesting to note that contextual effects on fathers’ share of care leave increase more steeply in the 10% most segregated areas, for all factors. This means contextual effects have the largest effect in the most segregated areas in terms of gender contracts. But overall, individual-level effects are much larger than contextual effects, which is as expected.

To check the robustness of our results, we conducted a few sensitivity analyses. Based on our earlier analysis, including a k-level of lower than 200 and perhaps more than 6,400 is not appropriate given the nature of how geographical context may impact on fathers’ share of care leave. We therefore conducted additional factor analyses for k-levels 1,600 and 6,400. Both factor analyses resulted in three factors. The interpretation of the factors resulting from the factor analysis using the 10 indicators for the 1,600 nearest neighbours is quite similar to that based on the k-200 level. Rotated factor loadings are quite similar, with only a slightly increased factor loading of unemployed women for the factor marginalization. So on a larger scale, the share of unemployment among nearest female neighbours also matters for the degree of marginalization. The factor analysis based on the 6,400 nearest neighbours shows an overall similar interpretation of the three factors, with the difference that factor 3, private sector, has a factor loading of high earning women of 0.317 in addition to the factor loadings on men and women working in the private sector, that were found in the factor analyses on the k-200 and k-1,600 level.

Adding these factors to the regression analysis leads to a slightly lower explained variance. Overall, the direction of effects for individual-level factors is similar. However, at the k-1,600 level, the effects of the factors representing local gender contracts are lower, and both the effects for elite and private sector are non-significant. At the 6,400 level, neither factor has a significant effect on fathers’ share of care leave, which further strengthens our choice for the k-200 level as the most appropriate scale level in the analyses.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we have examined how care leave is utilized by couples locally, by investigating whether fathers’ share of care leave use is associated with both individual-level determinants based on relative resources within the household, and neighbourhood-level operationalisations of the local gender contract. Part of our contribution was enabled by developments in geocoded big data, which open up new ways to examine local care leave use. Using unique geocoded register data, the study provided a more detailed and nuanced spatialized pattern of gendered care leave than previous studies have been able to give (Amcoff, 2001; Duncan, 2000; Forsberg, 1998). We also contribute to a rapidly expanding literature on contextual effects by a study focused on gendered care leave by using gender contract theory. In addition, by using a nearest neighbour and multiscalar approach, the many problems related to using administratively defined areas in spatial analyses are overcome. Using individualized neighbourhoods also contributes to our understanding of how family policy works at different geographic scales.

To address the contemporary geographical variation in fathers’ share of care leave, we used slightly over 100,000 individualized neighbourhoods at different geographic scales. Neighbourhoods were defined as areas around individual fathers with children in the age 0 to 6. Among the nearest 200 fathers with young children, an average of 41% of care leave was taken by fathers. In neighbourhoods with the highest share, men’s share of care leave is more than 50%, while in the areas with the lowest uptake, it is less than 32%. The multiscalar maps showed that geographical patterns of men’s care leave vary substantially by location, confirming the first hypothesis. The level of spatial clustering varies by scale level, with much more clustering at higher scale levels. Fathers’ share of care leave shows many local clusters, as also shown by the large variation in small-scale maps, such as in central Stockholm and around Jönköping. It is unlikely that these patterns are remnants of the previous system of local insurance agencies, as care leave is administered nationally (The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate, 2011).

We estimated the scale level of the nearest 200 fathers with young children to be most appropriate for examining contextual effects on men’s care leave. Maps at this scale level revealed considerable local variation without large-scale clustering, which may mean clustered gendered norms may be more important compared to considering very small or much larger scale levels.

The second question we asked is how fathers’ share of care leave is associated with individual as well as geographical determinants, with the latter representing different indicators of local gender contracts. Previous studies have indicated important factors that impact fathers’ share of care leave at the individual level, such as women’s educational level and partners’ reciprocal income levels. This study confirms that relative socio-economic characteristics of men and women play a very important role in explaining fathers’ share of care leave. In our study, we included five indicators of partners’ relative resources in the household. Fathers take a larger share in three groups of couples: fathers with midrange incomes with partners with low incomes; fathers with top incomes with partners with low incomes; and for couples where both have low incomes. This means that when women earn an income in the lowest quartile, their partners take on a larger part of care leave. It may be the case that these women are in jobs where it is challenging to take care leave on a last-minute basis, whereas it may be easier for their partners. A possible explanation may also be that these women have temporary jobs, such as hourly waged employment or are in on-call employment forms, and as such face employment vulnerabilities which does not allow them to make use of the care leave benefit. It may be that the income loss for very low incomes means that the income left is seen as too small, leading to a negotiation where the male partner is then taking the care leave. These findings are partly in line with Boye (2015b), who found that fathers’ care leave increases with decreasing women’s wages. However, relative resource theory would entail that the person with the lowest income would have the lowest bargaining power and therefore would end up with taking the care leave day, but we do not find that in our study. Men’s share of care leave is higher for couples where the woman is the high earner and the male partner has a midrange income, which is in line with what we expected, as the income loss is larger for the high earner compared to the midrange earner. Negotiations are part of local gendered norms and contextualized by both couple negotiations as well as the broader social context in which that household is situated suggesting a role for geography in understanding policy usage. However, the gender differences in these findings are unexpected and need further research. Another contribution to the family policy literature is that fathers’ share of care leave is highest for couples where both partners are higher educated, and for Swedish-born men that are married to or live together with migrant women.

Contextual effects on fathers’ share of care leave were operationalized using the concept of gender contracts, using 10 indicators of human capital, labour market structure and demography. These local gender contracts capture both a varying composition of the local population and local gendered norms. Our findings highlight the role of local characteristics to understand the results, a unique benefit of using gender contract theory. Factor analysis on these indicators revealed that three factors explained most of the local variance measured by these variables, labelled as elite, marginalisation and private sector. In a regression model, fathers’ share of care leave was found to be significantly associated with neighbourhood factors in addition to individual-level determinants, thereby confirming the second hypothesis. The results show that individual-level factors are far more important in explaining fathers’ share of care leave, and that contextual effects pertaining to local gender contract have a significant but moderate effect. However, living in the most segregated areas in terms of gender contracts does have a reasonable effect on gendered care leave, especially so for the most marginalized areas, which is associated with an increased share of father’s care leave. An increasing level of elite in the neighbourhood is also associated with an increased share of fathers taking care leave, while an increasing share of nearest neighbours working in the private sector is related to a decreased share of men staying home with sick children. Thus while differently characterized neighbourhoods emerge with similar results, it does highlight the importance of working forms in shaping gender contracts.

It may be that in the most marginalized areas, residents have less flexible jobs compared to less marginalized areas, and therefore need to take official care leave days more often. Fathers with higher incomes in more elite areas more often have flexible day schedules and may stay home with their children, with or without taking a care leave day. There is even a Swedish word for the latter, “vobbing”, which is a combination of the words for working, “jobba”, and taking care leave, “vabba”. Finally, being surrounded by a high share of neighbours working in the private sector is associated with a lower share of fathers staying home with their sick children, net of couple-level effects of working in the private sector, meaning that such concentrations have transmissible effects on fathers’ parental leave uptake.

As gender contracts are shaped by social interaction, using individualized neighbourhoods is an excellent tool to explore how local gender contracts influence gendered negotiations about care leave. Local gendered norms come about due to individual behaviours in specific places, such as fathers staying home with sick children. The premise of individualized neighbourhoods is that individuals are affected by their nearest neighbours rather than, often larger, administratively defined areas. Measuring local neighbourhood effects, or the effect of “peers”, in this case, by the presence of other fathers with young children, is in line with the mechanisms of neighbourhood effects, usually theorized as resulting from a joint effect of peer influence, role models and institutional models (see e.g. Sampson, 2012). This study has not been able to pinpoint through which mechanisms contextual effects affect fathers’ share of care leave, and we stimulate future studies of perhaps a mixed nature, to further investigate how local gender contracts and gendered care leave are connected.

A combination of relative resources within the couple and local gender contracts influences the negotiation and ultimate decision who will stay at home with a sick child. The tangled relations within a gender contract demonstrate that care outcomes are spatially produced and locally contingent. We also see gender contracts as carried out within contexts. With multiscalar patterns of gender contracts we see suggestions that negotiations are locally generated and thus in order to understand gendered relations or practices, considering the scale of gendered practices will yield different understandings. The choice of scale reveals intricacies in the patterns.

The results point at local variation in how care leave is shared in couples, but differences are moderate. Nevertheless, we do see local variations exist and this indicates a need for understanding the effects of geographical context on gendered family policy use. With the assertion of geography playing a role in how individuals act on policies, we call for more studies in other contexts, in particular outside of the Nordic context. Future studies on the use to family policies should therefore include the local context using geographical scales appropriate to the policies being examined. For studies on care leave, our findings indicate that couple negotiations are rooted in locally varying gender contracts.

Notes

Care leave is intended to be used for any illness a child that normally attends preschool or school may have, but it is mostly used for common illnesses such as colds, influenza or other common infections in children. In addition to using care leave for sick children, the leave can be used to accompany a child to the doctor, dentist and similar. Unemployed parents may use care leave instead of unemployment benefits when children are sick. For seriously ill children up to the age of 18, care leave is unlimited.

Developed by John Östh and freely available for non-commercial use through Uppsala University.

We had also included a variable measuring the share of high earning men, defined in similar terms to the variable for women, but because of too high correlation (> 0.9) with average income in the neighbourhood, this variable was excluded in the factor analyses (see Sect. 5.2).

The average share of fathers’ care leave among the nearest neighbours varies from 41.0% for the 50 nearest neighbours to 41.6% for the 25,200 nearest neighbours.

Factor 1 accounts for 40% of explained total variance, factor 2 for 14% and factor 3 for 9%.

Based on a likelihood ratio test between the individual and the neighbourhood model.

References

Adu-Gyamfi, A., Brandful Cobbinah, P., & Poku-Boansi, M. (2019). Positionality of women in homeownership: A process of gender contract negotiation. Housing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1690131

Almqvist, A.- L., Sandberg, A., & Dahlgren, L. (2010). The fathers and the motives. Swedish paid parental leave in a geographical perspective. Working Papers in Social Insurance 2010: 1. Stockholm: Swedish Social Insurance Agency.

Alsarve, J., Boye, K., & Roman, C. (2019). Realized plans or revised dreams? Swedish parents’ experiences of care, parental leave and paid work after childbirth. In D. Grunow & M. Evertsson (Eds.), New parents in Europe: Work-care practices, gender norms and family policies (pp. 68–85). Edward Elgar.

Amcoff, J. (2001). Regionala genuskontrakt i Sverige? [Regional gender contracts in Sweden?] Unpublished paper, Uppsala University.

Amilon, A. (2007). On the sharing of temporary parental leave: The case of Sweden. Review of Economics of the Household, 5(4), 385–404.

Andersson, E. K., & Malmberg, B. (2015). Contextual effects on educational attainment in individualised, scalable neighbourhoods: Differences across gender and social class. Urban Studies, 52(12), 2117–2133.

Andersson, E. K., & Malmberg, B. (2018). Segregation and the effects of adolescent residential context on poverty risks and early income career: A study of the Swedish 1980 cohort. Urban Studies, 55(2), 365–383.

Andersson, E., Malmberg, B., Costa, R., Sleutjes, B., Stonawski, M. J., & De Valk, H. (2018). A comparative study of segregation patterns in Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden: Neighbourhood concentration and representation of non-European migrants. European Journal of Population, 34(2), 251–275.

Åström, G., & Hirdman, Y. (1992). Kontrakt i kris. Om kvinnors plats i väldfärdsstaten [Contracts in crisis. Women's place in the welfare state]. Carlssons.

Boye, K. (2015a). Care more, earn less? The association between care leave for sick children and wage among Swedish parents. IFAU Working Paper 2015: 18. Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy, Uppsala.

Boye, K. (2015). Can you stay at home today? Parents’ occupations, relative resources and division of care leave for sick children. Acta Sociologica, 58(4), 357–370.

Caretta, M. A. (2015). Hydropatriarchies and landesque capital: A local gender contract analysis of two smallholder irrigation systems in East Africa. The Geographical Journal, 181(4), 388–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12102

Caretta, M. A., & Börjeson, L. (2015). Local gender contract and adaptive capacity in smallholder irrigation farming: A case study from the Kenyan drylands. Gender, Place & Culture, 22(5), 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.885888

Clark, W. A. V., Anderson, E., Östh, J., & Malmberg, B. (2015). A multiscalar analysis of neighborhood composition in Los Angeles, 2000–2010: A location-based approach to segregation and diversity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(6), 1260–1284.

Duncan, S. (1994). Theorising Differences in Patriarchy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 26(8), 1177–1194.

Duncan, S. (1995). Theorizing European gender systems. Journal of European Social Policy, 5(4), 263–284.

Duncan, S. (2000). Introduction: Theorising comparative gender equality. In S. Duncan & B. Pfau-Effinger (Eds.), Gender, economy and culture in the European Union (pp. 1–23). Routledge.

Duncan, S., & Pfau-Effinger, B. (2000). Gender, economy and culture in the European Union. London: Routledge.

Duvander, A.-Z., & Johansson, M. (2012). What are the effects of reforms promoting fathers’ parental leave use? Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 319–330.

Eriksson, H. (2011). The gendering effects of Sweden’s gender-neutral care leave policy? Population Review, 50(1), 156–169.

Eriksson, R., & Nermo, M. (2010). Care for sick children as a proxy for gender equality in the family. Social Indicators Research, 97(3), 341–356.

Ferrarini, T., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2010). Earner-carer model at the cross-roads: Reforms and outcomes of Sweden’s family policy in comparative perspective. International Journal of Health Services, 40(3), 373–398.

Fisher, C. S., Stockmayer, G., Stiles, J., & Hout, M. (2004). Distinguishing the geographical levels and social dimensions of US metropolitan segregation, 1960–2000. Demography, 41(1), 37–59.

Forsberg, G. (1997). Rulltrapperegioner och social infrastuktur [Escalator regions and social infrastructure]. In E. Sundin (Ed.), Om makt och kön. I spåren av offentliga organisationers omvandling. Statens Offentliga Utredningar 1997: 83 (pp. 31–68). Ministry of Employment.

Forsberg, G. (1998). Regional variations in the gender contract: Gendered relations in labour markets, local politics and everyday life in Swedish regions. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 11(2), 191–209.

Forsberg, G. (2001). The difference that space makes. A way to describe the construction of local and regional gender contracts. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 55(3), 161–165.

Forsberg, G. (2010). Gender, geography and social practice. In: B. Hermelin, & U. Jansson (Eds.), Placing geography. Sweden through time and space (pp. 209–222). Stockholm: YMER, Svenska Sällskapet för Antropologi och Geografi.

Forsberg, G., & Stenbacka, S. (2017). Creating and challenging gendered spatialities: How space affects gender contracts. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 99(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2017.1303269.

Forsberg, G., Gonäs, L., & Perrons, D. (2000). Paid work: Participation, inclusion and liberation. In S. Duncan & B. Pfau-Effinger (Eds.), Gender, economy and culture in the European Union (pp. 27–49). Routledge.

Forsberg, G., Grimsrud, G. M., Jakobsen, L., Jansdotter, M., & Vangsgraven Stubberud, K. (2006). Gränsfall: Platsens betydelse för omställning och utveckling i en gränsregion [Border cases: The importance of place for adjustment and development in a border region]. Nordregio.

Forsberg, G., & Lindgren, G. (2015). Regional policy, social networks and informal structures. European Urban and Regional Studies, 22(4), 368–382.

Forsberg, G., & Stenbacka, S. (2013). Mapping gendered ruralities. European Countrysides, 1, 1–20.

Fowler, C. (2016). Segregation as a multiscalar phenomenon and its implications for neighborhood-scale research: The case of South Seattle 1990–2010. Urban Geography, 37(1), 1–25.

Geisler, E., & Kreyenfeld, M. (2011). Against all odds: Fathers’ use of parental leave in Germany. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(1), 88–99.

Gerrard, S. (2017). Mobility practices and gender contracts: Changes in gender relations in coastal areas of Norway’s High North. Nordic Journal on Law and Society, 1(1–2), 91–113.

Gil Solá, A. (2016). Constructing work travel inequalities: The role of household gender contracts. Journal of Transport Geography, 53, 32–40.

Goldstein-Gidon, O. (2019). The Japanese corporate family: The marital gender contract facing new challenges. Journal of Family Issues, 40(7), 835–864. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19830147

Golovina, K. (2018). Gender contract in online commercials in Japan: A critical investigation of the contemporary discourse on the work-life balance [Гeндepный кoнтpaкт в oнлaйн-peклaмe в Япoнии: кpитичecкий aнaлиз coвpeмeннoгo диcкypca «бaлaнcapaбoты—жизни»]. The Russian Sociological Review, 17(1), 160–191. English version.

Grimsrud, G. M. (2011). Gendered spaces on trial: The influence of regional gender contracts on in-migration of women to rural Norway. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 93(1), 3–20.

Gustafsson, S. (1992). Separate taxation and married women’s labor supply. A comparison of West German and Sweden. Population Economics, 5, 61–85.

Haandrikman, K. (2019). Partner choice in Sweden: How distance still matters. Environment and Planning A, 51(2), 440–460.

Haandrikman, K., Webster, N. A., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2021). Geographical variation in local gender contracts in Sweden. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-020-09371-2

Häyrén-Weinestål, A. (2010). Kan man diskriminera kvinnor? Har kvinnor sämre arbetsvillkor än män i akademin? [Can one discriminate against women? Do women have worse working conditions than men in the academy?]. In P. De-Los-Reyes (Ed.), Vad händer med jämställdheten? Nedslag i jämställdhetens synfält (pp. 62–82). Uppsala University.

Hedfeldt, M. (2008). Företagande kvinnor i bruksort: Arbetsliv och vardagsliv i samspel [Self-employment women in small industrial towns: The interaction between work life and everyday life]. Örebro University.

Hennerdal, P., & Nielsen, M. M. (2017). A multiscalar approach for identifying clusters and segregation patterns that avoids the modifiable areal unit problem. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(3), 555–574.

Hirdman, Y. (1992). Introduktion [Introduction]. In G. Åström & Y. Hirdman (Eds.), Kontrakt i kris (pp. 7–14). Carlsson.

Hirdman, Y. (1993). Genussystemet. Reflexioner kring kvinnors sociala underordning [The gender system. Reflections on women's social subordination]. In C. Ericsson (Ed.), Genus i historisk forskning (pp. 49–63). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Ichino, A., Olsson, M., Petrongolo, B., & Skogman Thoursie, P. (2019). Hur påverkar ekonomiska incitement och könsnormer fördelningen av barnomsorg mellan föräldrar? [Economic incentives, home production and gender identity norms]. IFAU Rapport 2019: 13. Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy, Uppsala.

Kalabamu, F. (2005). Changing gender contracts in self-help housing construction in Botswana: the case of Lobatse. Habitat International, 29, 245–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2003.09.005

Kashina, M., & Tkach, S. (2020). Fatherhood escape as a significant feature of the gender contract of Russian men. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-09-2020-0426

Klinth, R. (2002). Göra pappa med barn. Den svenska pappapolitiken 1960–1995 [Making daddy pregnant: The Swedish papa politics 1960–1995]. Umeå: Borea.

Kwan, M.-P. (2012). The uncertain geographic context problem. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(5), 958–968.

Leira, A. (2002). Updating the “gender contract”? Childcare reforms in the Nordic countries in the 1990s. Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 10(2), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/080387402760262177

Lindeborg, A-K. (2012). Where gendered spaces bend. The rubber phenomenon in northern Laos. Ph.D. dissertation. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

Ma, L., Andersson, G., Duvander, A.-Z., & Evertsson, M. (2019). Fathers’ uptake of parental leave: Forerunners and laggards in Sweden, 1993–2010. Journal of Social Policy, 49(2), 361–381.

Malmberg, B., & Andersson, E. K. (2015). Multi-scalar residential context and recovery from illness: An analysis using Swedish register data. Health and Place, 35, 19–27.

Malmberg, B., Andersson, E. K., & Bergsten, Z. (2014). Composite geographical context and school choice attitudes in Sweden: A study based on individually defined, scalable neighborhoods. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(4), 869–888.

Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.