Abstract

This paper draws on three data sources – a national survey from Germany of adult literacy and numeracy skills (leo. – Level-One Study), the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC), and case studies of workplaces in England – to argue for a greater focus by policymakers and researchers on the literacy demand experienced by adults.

We consider the heterogeneity of the population of adults deemed functionally illiterate by large-scale national and international surveys and question how such a large group of adults are indeed able to function in society. We draw on concepts of literacy practices and the literate environment to try to understand the demands on adults’ reading and writing and suggest that adults with poor literacy skills may be reluctant to engage in learning because they experience very low demand. Engagement in literate practices is an important mechanism through which literacy is improved and developed. If the demands on many adults’ literacy are so low, their skills may decline/fail to develop, leaving a large sub-class excluded from the literate environment and relying on others for interpretation and access to information. This vicious circle of underuse and consequent loss of skills should be a major concern for policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper is concerned with adult literacy (reading and writing) and the role that it plays in adults’ everyday lives. In it we will argue that policy makers and researchers should focus on the literacy demands on adults in their everyday lives in order to better design policies to support them in meeting these demands.

We live in a world in which literacy plays an increasingly important role:

In societies dominated by the written word, it is a fundamental requirement for citizens of all ages in modern Europe. Literacy empowers the individual to develop capacities of reflection, critique and empathy, leading to a sense of self-efficacy, identity and full participation in society. Literacy skills are crucial to parenting, finding and keeping a job, participating as a citizen, being an active consumer, managing one’s health and taking advantage of digital developments, both socially and at work (EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy 2012, p. 11).

And one in which, as a consequence, poor literacy is deemed to have a high price, for individuals and for societies.

As the demand for skills continues to shift towards more sophisticated tasks, as jobs increasingly involve analysing and communicating information, and as technology pervades all aspects of life, those individuals with poor literacy and numeracy skills are more likely to find themselves at risk … and countries with lower levels of skills risk losing in competitiveness as the world economy becomes more dependent on skills (OECD 2013a, p. 27).

Yet, over the past two decades, a number of large-scale national (Williams et al. 2003; BIS 2011; Grotlüschen and Riekmann 2011; Jeantheau 2007; ANLCI 2013) and international (Kirsch 2001; OECD and Statistics Canada 2005; OECD 2013a) surveys have identified that a sizable proportion of the working age population have low levels of literacy skills. This has lead to concerted efforts by governments in many countries to increase the supply of literacy skills in their countries through development of basic education programmes for adults.

It is common for policy makers, when discussing the supply of literacy skills, to speak in terms of functional literacy, that is, the level of literacy skills adults need to function in society. In German adult education policy rhetoric, for example, literacy is used as a dichotomous concept, with a stated level deemed necessary to “function” in society. Those who are assessed below that level are deemed “functionally illiterate” and may be targeted for learning provision. The term “functionally illiterate” is used for adults who are able to read and write simple, single words but have difficulties with reading and writing even short sentences (Boltzmann et al. 2013, p. 34). In Germany, 7.5 million people between 18 and 64 years, or 14.5 % of the adult population are considered functionally illiterate (Grotlüschen and Riekmann 2011). And Germany is not alone in this. In the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills, in the Netherlands, which was among the best performing countries in the literacy assessments, 11.7 % scored at or below Level 1, suggesting that 1.3 million Dutch adults of working age are functionally illiterate (Grotlüschen et al. 2016, p. 140).

There are two observations to be made about this. Firstly, this implies that an extremely large proportion of the population are not considered able to “function” in society, with literacy identified as a root cause. This is often framed in terms of a literacy crisis. Secondly, closer examination of this functionally illiterate population, made possible through analysis of the data generated by the aforementioned large-scale national and international surveys, leads us to question the extent of the personal and economy-wide consequences (Munteanu et al. 2014) deemed to be caused by poor literacy. For example, while this population are more likely than the rest of the adult population to be unemployed, the majority of them are not (Grotlüschen et al. 2016, p. 140).

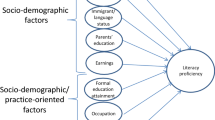

This leads us to therefore ask, how does this population, the functionally illiterate, manage their lives? What are they doing in the workplace and outside of it? How are they supported or hindered by the environment in which these practices take place? And why is it that despite their level of literacy being described as too poor for them to function in society, they appear to be able to do so? The central argument in this paper is that in asking these questions we need to consider, not just the individual’s level of literacy, their skills, as measured by large scale assessments, but their environment. The level of the skills in the population is an issue of supply and policy is active in the supply side with much attention given to the supply system of education provision: teachers, their training, curricula, materials, progression systems, and assessment. The key metric of such supply-driven policy is the literacy levels of “the workforce” as measured by, for example, the OECD’s survey of adult skills, PIAAC. However, the requirements placed on those skills in the daily lives of adults, in all domains, the practices that adults are required and/or encouraged to engage in, is an issue of demand. We suggest that by considering demand alongside supply we will be better able to formulate policy.

2 Data sources

Three data sources are drawn on in this paper: leo – the Level One Study (Grotlüschen and Riekmann 2011), the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills (OECD 2013a), and a UK government funded study into the impact of poor basic literacy and numeracy on employers (Carpentieri et al. 2016b).

leo. – the Level-One Study was a 2010 national survey of the literacy and numeracy skills of the adult population in Germany. The study provided national, reliable and differentiated data on literacy – i. e. the ability to deal with written text by reading and writing, by understanding and producing meaning – for the lowest competence levels of reading and writing. The Level-One Study comprised of a random sample of 7035 people and an additional random sample of 1401 people at the lower end of the educational scale. Skills tests were carried out on the sample after a standard survey on various aspects of people’s situations in life and attitude to further education.

The Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) assessed the proficiency of adults from age 16 onwards in literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments. In addition, the survey collected a range of information on the reading-related activities of respondents, the use of information and communication technologies at work and in everyday life, and on a range of generic skills. In the first round of PIAAC 166,000 adults aged 16 to 65 were surveyed in 24 countries and sub-national regions. The first results of PIAAC were published by OECD in 2013. This paper also draws on subsequent analysis of the PIAAC data on those who scored at or below Level 1 (Grotlüschen et al. 2016).

The BIS Employer Impact study (Carpentieri et al. 2016b) estimated the economic impact of poor basic skills on workplace performance. The study, undertaken by IPSOS MORI in partnership with the National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy (NRDC)Footnote 1 at the UCL Institute of Education, London, aimed to address the lack of evidence on the prevalence of poor basic skills in the workplace and its impact, as well as the costs and benefits associated with public-funded basic skills training. This study drew on a nationally representative survey of over 4000 workplaces in England to estimate the prevalence of poor basic skills in the workplace and in-depth follow-up case studies combining participant observation and employer and employee interviews at nine workplaces.

Together these three data sets provide an opportunity to consider issues of literacy supply and demand. leo and PIAAC allow us to paint a picture of the supply of adult literacy skills within and across countries, and to consider the impact of poor literacy on individuals and society. The BIS Employer Impact data provides an insight into the demands on individuals and the relationship between their skills development and those demands.

3 The “functionally illiterate” population

There has been a steady critique of the functional illiterate discourse since IALS (see for example Hamilton and Barton 2000, Levine 1982, Maddox et al. 2011, Payne 2006), which we will not repeat here. Nor does this paper go into country comparisons. On the release of the results of the Survey of Adult Skills (OECD 2013a), much media attention was given to these – the position of countries relative to the other participating countries in terms of performance in the literacy assessments.

However, comparison of performance in literacy between different countries is of limited use. Rather, in this paper we make the observation that all countries have a sizeable adult population with literacy needs. And for our discussion of literacy as supply and demand what matters less is the relative size of each country’s own population of adults with poor literacy and numeracy as measured in large scale national or international assessments such as leo or PIAAC, or what a country’s average performance is against comparator countries, and more on understanding the particular characteristics of those who performed poorly in these surveys.

Analysis of data from the 2010 German Level-One Study (Grotlüschen and Riekmann 2011) found 7.5 million “functionally illiterate” adults (i. e. scoring at Alpha levels 1–3) between the ages of 18 to 64 in Germany: 14 % of the working age population. A further 25 % of the working age population in Germany (13.3 million people) had poor writing skills, and poor spelling in particular. These figures were far higher than was thought, with previous estimates of 4 million Germans with functional illiteracy.

A similar picture emerges from the Survey of Adult Skills. Data from PIAAC show that a significant proportion of the adult population in all participating countries performed poorlyFootnote 2 in the literacy assessments. Across the whole sample 15.5 % of adults, between one in six and one in seven, scored at or below Level 1 in literacy. The size of the group differs between countries. Italy (27.7 %), Spain (27.5 %), France (21.6 %) and Poland (18.8 %) have substantially higher proportions of adults who scored at or below Level 1 compared to the average. However, even those countries that appeared to “do well” in the survey, such as Finland (10.6 %), the Slovak Republic (11.6 %), the Netherlands (11.7 %) and the Czech Republic (11.8 %), have a large number of adults of working age with poor skills in literacy (Grotlüschen et al. 2016, p. 19).

Crucially, however, while those who scored at or below Level 1 in literacy are more likely than the rest of the adult population to exhibit certain characteristics, the difference between those who scored at or below Level 1 and the rest of the adult population is a question of degree rather than one of clear differentiation. For example, those with poor literacy are more likely than the rest of the adult population to have not completed upper secondary level education and they are also more likely to have been born in a country other than the country in which they took the test. However, while they are more likely than the rest of the adult population to exhibit these characteristics, the majority of them do not. Indeed, 65 % completed upper secondary (and 9 % completed tertiary); and 62 % were born in the country in which they took the test. Or, to take another example, while adults who scored at Level 1 and below in literacy are more likely than adults at higher levels to be unemployed, they are, nevertheless, much more likely to be employed than unemployed. 56 % of those who scored at or below Level 1 in PIAAC are in employment and only 10 % are unemployed, as compared to 8 % of those who scored at Level 2 and 3 % of those who scored at Levels 4/5 (Grotlüschen et al. 2016, p. 133).

In other words, neither the leo. study nor PIAAC reveal a homogenous group of adults with low literacy skills. Instead, they reveal great variation in the characteristics of this group, both within and across countries. That such a sizeable proportion of the population is measured as having lower than functional skills in literacy demonstrates the potential size of the challenges countries face in improving the literacy levels of their adult population. This is compounded by the heterogeneous nature of this population of adults, meaning that, when seeking to increase the supply of basic skills among the adult population, there is no simple, clear target for policy makers to aim at.

Our understanding of this “functionally illiterate” population may be further complicated by our knowledge of adults who join adult basic skills classes. To take Germany as an example: comparison between the results of the leo. study and the representative learner study “AlphaPanel”,Footnote 3 which contains data on adult learning in Germany, shows that learners on adult basic education courses are more likely to be unemployed, to suffer from poorer health, and are far more likely to have had a negative experience of school than the whole population. This is a picture that will be familiar to those who work in adult basic education in England and other countries where there are many learners who share these characteristics. More importantly, what these data indicate is that, while there is overlap, the functionally illiterate population and the adult literacy learner population are not the same. If our understanding of the low-proficiency population is less than accurate, there is a danger that stereotypes may inform policy in the area of adult basic education (Grotlüschen et al. 2016, p. 3). The view that adults with low literacy and numeracy are predominantly unemployed, poorly educated or from immigrant or low socio-economic status backgrounds means that governments may target literacy training at those adults who are seen as being within the most at-risk groups: migrants, the unemployed or those without secondary education. However, this risks ignoring the needs of large numbers of adults who also need to improve their skills. This is compounded by the fact that those with poor literacy skills are already less likely to engage in learning. While the overall average participation rate in adult education is 46 % among the whole population, only one in three of those who scored at or below Level 1 in literacy had participated in adult education in the 12 months prior to the survey of adult skills (Grotlüschen et al. 2016, p. 142).

4 Demand

We have so far established that there is a sizeable proportion of the adult working population that has literacy skills, as measured in large-scale national and international assessments, below the level deemed necessary to function effectively in society. And yet, the large majority of these adults are not taking steps to improve their skills by engaging in adult education courses. This suggests that the adult education solutions that are on offer aren’t the “right” kind for many people within this population. Or perhaps that they do not think that they need to improve their literacy skills in the first place.

It also leads us to question how these adults, the so-called, “functionally illiterate”, manage in all of the domains of their lives. How do they function in our increasingly textualised world (EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy 2012, p. 11). In asking this question we need to consider, not just the individual’s literacy skills level, but the literacy demands made on that individual by his or her environment. And we need to ask whether adults need the literacy and numeracy skills at the levels we specify as functional or whether they can survive, and even prosper, without them. What are the literacy practices that they do engage in and how are they supported, or hindered, by the environment in which these practices take place?

As part of the BIS Employer Impact study (Carpentieri et al. 2016b) a series of case studies of English workplaces were carried out. These were designed to illustrate and help explain the results of in an in-depth survey of more than 4000 employers. The survey asked respondents what percentage of a certain category of worker in their workplace were required to complete certain tasks and what percentage of those people they were confident could complete such tasks. This allowed for the identification of literacy “gaps”. The definition of a “gap” employed in the study was “any workplace reporting that at least one member of staff is unable to perform one or more of the literacy tasks to the level required in their day-to-day job” (Carpentieri et al. 2016a, p. 22). The literacy tasks that respondents were asked about were:

-

fully understand written procedures (e. g. for using equipment, machinery, or administrative processes),

-

complete day-to-day paperwork without errors (e. g. end of shift reports, Health & Safety reports; activity logs),

-

respond in writing (e. g. by letter or email) to queries or complaints from clients, colleagues or sub-contractors,

-

communicate verbally with clients, colleagues or subcontractors.

Real-world tasks were selected as it was felt that the abstract notion of “literacy” would be difficult for respondents to conceptualise and estimate.Footnote 4 Overall, 8 % of workplaces surveyed reported a literacy skills gap. This is lower than previous findings from the Employer Skills Survey (ESS) in 2013, in which 12 % of workplaces said their employees’ literacy needed improving or updating in the next 12 months. However, in the ESS employers were asked to estimate their employees’ literacy skills rather than their ability to carry out specific tasks.

Understanding written procedures and communicating verbally were the most frequently cited skills required by employers, suggesting that these are seen as what everyone needs to know in the workplace. Responding in writing was the least cited and also boasted the widest skills gap in comparison to the other categories. However, overall the picture painted by the survey was not one in which reading and writing was a major concern for employers.

For the case studies, we spoke to owners, directors, HR managers and other employees in many different occupational roles and levels. We found little anxiety about reading and writing. We did not find that they felt that their employees’ skills were uniformly good, instead they felt that reading and writing tasks in the workplace were distributed effectively, and the demands in some roles minimal.

The text practices that we observed in the workplaces we visited were varied. There was great diversity of types of texts and these needed to be “acted on” or “reacted to” in different ways. Some texts were intended to be read, or to be read aloud to someone listening, or to be read and acted on immediately. However, many of the texts that we encountered were little more than artefacts, representative of agreement, or acceptance, but certainly not intended to be read.

Many of the workplaces visited also had quite sophisticated systems of scaffolding for their employees’ reading and writing in the form of templates and processes that reduced the requirements for employees to use anything other than basic reading and writing skills. Scaffolding, a term drawn from educational psychology (Wood et al. 1976, p. 90), describes helpful, structured support provided by any external source that allows an individual to work beyond their current independent development level. It can be pre-planned in the form of structures and templates or contingent (Hammond and Gibbons 2005, p. 20) as individuals work in collaboration to complete tasks. This explicit scaffolding of tasks requiring reading and writing may mask or obviate basic skills deficits among employees. However, it may also exacerbate and systematize them. Adults are unlikely to feel the need to improve their reading and writing if they are not required to use them. This may in part explain the low demand for adult basic education courses.

5 Skills use

We believe that the distinction between supply and demand can help us analyse policy and our role within it. The level of the skills in the population is an issue of supply, the requirements placed on those skills in the daily lives of adults, in all domains including but not limited to the workplace, is an issue of demand. The key metric of supply-driven policy is the literacy and numeracy levels of the workforce as measured by, for example, the OECD’s survey of adult skills, PIAAC. The model of literacy that underpins PIAAC is skills based. Reading and writing are understood as a set of skills that can be measured separately to provide a picture of the literacy health of a nation. However, it can be argued that what is most important in literacy development is not what people are able to do, but what in fact they do; their practices, not their skills. However, skills are easy to measure, and practices aren’t, and so we accept the measurable and try to apply its lessons, ignoring that which is less measurable but may be of equal significance.

Of course PIAAC does include limited, but useful, measures of practices and this data on how adults make use of their skills can be shown to highlight the importance of engagement with literacy. We learn that large numbers of low-proficiency adults have limited engagement with reading, writing, and numeracy practices at work and outside work.

There is broad cross-national variation in levels of engagement in various information-processing practices among adults with low-proficiency in literacy. However, it is possible to discern patterns in the data. As literacy proficiency levels rise, average levels of engagement in reading and writing practices increase steadily. We also see that adults’ uses of a given skill are highly correlated between work and outside of work. Engagement with each domain of practice is positively correlated between work and outside of work settings, at both the level of individuals and countries. These correlations are found in both the low-proficiency and the broader adult populations. In PIAAC adults who engage in more reading practices score at higher levels of proficiency in reading. While it is not possible to demonstrate a causal relationship here, that is, we do not know if the practices lead to greater proficiency or if those with higher proficiency are more likely to engage in more practices, OECD conclude that:

adjusting for educational attainment and language status reveals that the positive relationship between practice and proficiency is strong. That is, adults who practice their literacy skills nearly every day tend to score higher, regardless of their level of education. This suggests that there might be practice effects (…) that influence proficiency (OECD 2013a, p. 212).

That a high proportion of adults with literacy at or below Level 1 make little use of their literacy skills at work likely indicates that they are working in jobs that demand little in terms of their literacy skills. And, if engaging in practices develops skills proficiencies and prevents skills loss (OECD 2013b, p. 24), then they therefore run the risk of losing the skills that they do have by not using them.

These findings support Reders’ Practice Engagement Theory (Reder 2009) developed from his Longitudinal Study of Adult Learning, which provides a framework for understanding how everyday literacy practices and proficiencies mutually influence each other.

6 The literate environment

A focus on practices, what adults do, not what they are capable of doing, leads us to consider more carefully the demand on adults’ literacies in every form. For us to be able to design attractive and motivating learning opportunities we need to better understand the literacy requirements of active engagement in society. Such learning should support adults in engaging in the literacy practices that are important to them.

In their discussion of the implications of the data from the Survey of Adult Skills OECD talk about acting to prevent a vicious cycle in which low proficiency and limited opportunities to maintain and develop proficiency become mutually reinforcing (OECD 2013b). The use of “opportunities” here echoes the recommendations made by the European Commission High Level Group of Experts on literacy (European Commission 2012)Footnote 5. In their final report they concluded that adults’ skills respond to and are shaped by the “literate environment” in which they act. The literate environment constitutes the demands on and supports for adults’ literacy in any particular domain. The HLG concludes that adults should be encouraged to read and to write more often and to be supported in doing so with greater confidence and enjoyment. This is a demand as much as a supply-side issue.

PIAAC data on skills use provides strong support for the High Level Group’s emphasis on policy proactively fostering a more literate environment – that is, creating more, and better, opportunities for literacy engagement in all areas of individuals’ lives. And not just opportunities, we also need to increase people’s desire to engage more closely with the texts that mediate their lives and we need to support them in doing so, not least through the design of learning that leads to more confident engagement with the literate environment.

7 Conclusion

The three data sets that form the evidence base for this study share a common focus on adult literacy. PIAAC and Leo both provide a rich source of information on the supply of skills, allowing for quantitative exploration of a very wide range of variables in relation to performance in literacy. PIAAC also has limited measures of Skills Use – demand for skills in the workplace and at home. The case study data from the BIS Employer Impact study focuses on issues of literacy demand, in this case in the workplace, and helps us to interpret findings from the PIAAC data. This highlights the importance of the use of qualitative data in understanding the results of large-scale international assessment exercises such as PIAAC. Finally, in this paper we have only considered these issues from the perspective of literacy. However, in each of the three studies numeracy data was also collected. Analysis of this is likely to find many similarities in the relationship between literacy and numeracy, and life outcomes, as well as some interesting differences. Further research should fill this gap in our understanding.

Evidence suggests that encouraging more intense engagement in literate practices is an important mechanism through which literacy is improved and developed. PIAAC data show that adults with literacy at or below Level 1 are much more likely than the general population to report never engaging in literate practices such as reading writing, at home or at work. If many adults are working in jobs that demand little in terms of their literacy skills it is not surprising that they are reluctant to seek to improve their skills through engagement in basic education courses. The situation is exacerbated by the nature of many such courses, which focus on improving work functionality rather than engaging adults in developing their literate and numerate practices in contexts that are more meaningful to them. If the demands on many adults’ literacy are so low, their skills may decline/fail to develop, leaving a large sub-class excluded from the literate environment and relying on others for interpretation and access to information. This vicious circle of underuse and consequent loss of skills should be a major concern for policy makers.

Policy makers need to be active in developing systems to ensure the supply of literacy and numeracy skills among the population. However, policymakers should also invest in the general literate environment to compensate for the lack of engagement that adults with low literacy may have at work. In order to find ways to motivate adults with low-proficiency in literacy and/or numeracy to engage in learning we also need to know about the demand for literacy and numeracy. What are adults required to do with their literacy and numeracy skills? What demands does the literate environment in which they work place on their literacy and numeracy skills? Understanding demand would allow policy makers to design learning that will help adults to meet those demands as well as credibly demonstrate to employers, and others that they can meet those demands.

Notes

That is, scored at or below Level 1.

The AlphaPanel (Lehmann et al. 2012), is a study of German adult learners, representative of those on German Adult Basic Education courses in German “Volkshochschulen” (adult education centres). It has a sample size of n = 524 (for more information see ibid.).

See Carpentieri et al. (2016a) for a discussion of the literature that informed the design of the survey, in particular the formulation of the survey items designed to identify literacy “gaps”.

European Commission (2012). EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy. Final Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

References

ANLCI (2013). L’évolution de l’illettrisme en France. Lyon: ANLCI.

BIS (2011). The 2011 skills for life survey: a survey of literacy, numeracy and ICT levels in England. London: BIS.

Boltzmann, M., Rüsseler, J., Zheng, Y. E., & Münte, T. F. (2013). Learning to read in adulthood: an evaluation of a literacy program for functionally illiterate adults in Germany. Problems of education in the 21st century, 51, 33.

Bynner, J., & Parsons, S. (2006). New light on literacy and numeracy: full report. http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/22308/1/doc_3276.pdf

Carpentieri, J., Litster, J., & Mallows, D. (2016a). Impact of poor english and maths skills on employers: literature review. London: BIS.

Carpentieri, J. D., Colahan, M., Hale, C., Litster, J., Mallows, D., & Trinh, T. (2016b). Impact of poor basic literacy and numeracy on employers BIS research paper number 266. London: BIS.

EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy (2012). Act Now! Final Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Grotlüschen, A., & Riekmann, W. (2011). leo. – Level-One Study: Literacy of adults at the lower rungs of the ladder. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg.

Grotlüschen, A., Riekmann, W. and Buddeberg, K. (2014). Stereotypes versus Research Results Regarding Functionally Illiterate Adults. Hamburg: University of Hamburg. http://blogs.epb.uni-hamburg.de/leo/files/2014/10/Grotlueschen-et-al.-2014-Stereotypes.pdf. Last accessed: 21. July 2016.

Grotlüschen, A., Mallows, D., Reder, S., & Sabatini, J. (2016). Adults with Low Proficiency in Literacy or Numeracy, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 131. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Hamilton, M., & Barton, D. (2000). The International Adult Literacy Survey: What does it really measure? International Review of Education, 46(5), 377–389.

Hammond, J., & Gibbons, P. (2005). Putting scaffolding to work: The contribution of scaffolding in articulating ESL education. Prospect, 20(1), 6–30.

Jeantheau, J. P. (2007). IVQ Erhebung 2004/2005 : Schwerpunkt ANLCI, Modul and erste Ergebnisse. In A. Grotlüschen & A. Linde (Eds.), Literalität, Grundbildung oder Lesekompetenz. Münster: Waxmann.

Kirsch, I. (2001). The International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS): understanding what was measured. New Jersey: ETS.

Lehmann, R., Fickler-Stang, U., & Maué, E. (2012). Zur Bestimmung schriftsprachlicher Fähigkeiten von Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmern an Alphabetisierungskursen. In A. Grotlüschen & W. Riekmann (Eds.), Funktionaler Analphabetismus in Deutschland (pp. 122–134). Münster, New York: Waxmann.

Levine, K. (1982). Functional Literacy: Fond Illusions and False Economies. Harvard Educational Review, 52(3), 249–266.

Maddox, B., & Esposito, L. (2011). Sufficiency re-examined: a capabilities perspective on the assessment of functional adult literacy. Journal of Development Studies, 47(9), 1315–1331.

Munteanu, C., Molyneaux, H., Maitland, J., McDonald, D., Leung, R., Fournier, H., & Lumsden, J. (2014). Hidden in plain sight: low-literacy adults in a developed country overcoming social and educational challenges through mobile learning support tools. Personal and ubiquitous computing, 18(6), 1455–1469.

OECD and Statistics Canada (2005). Learning a living: first results of the adult literacy and life skills survey. Paris Ottawa: OECD and Statistics Canada.

OECD (2013a). Skills outlook: first results from the survey of adult skills. Paris: OECD.

OECD (2013b). Skilled for life? Key findings from the survey of adult skills. Paris: OECD.

Payne, G. (2006). Re-counting “illiteracy”: literacy skills in the sociology of social inequality. The British Journal of Sociology, 57, 219–240. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00107.x.

Reder, S. (2009). Scaling up and moving in: Connecting social practices views to policies and programs in adult education. Literacy and Numeracy Studies, 16(2), 35–50. 17 (1).

Williams, J., Clemens, S., Oleinikova, S., & Tarvin, K. (2003). The Skills for Life Survey: a National Needs and Impact Survey of Literacy, Numeracy and ICT skills. London: Department for Education and Skills Research. Report 490.

Wood, D. J., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 17(2), 89–100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieser Artikel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) veröffentlicht, welche die uneingeschränkte Nutzung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe für beliebige Zwecke erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallows, D., Litster, J. Literacy as supply and demand. ZfW 39, 171–182 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-016-0061-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-016-0061-1