Abstract

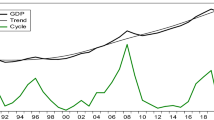

How have social movements in the United States been impacted by simultaneously evolving economic realities such as episodes of development and inequality across time? This paper empirically examines how the structural forces of the economy such as growth (income per-capita) and decline (income inequality) interact with the regional characteristics to derive patterns of social movements in United States from 1960 to 1995. I suggest that—unlike the arguments found in popular social movement theories such as relative deprivation and economic grievances that the society will express resentment against lack of financial resources through protesting and riots—there will be less collective action formations during heightened inequality even when there is growth in per-capita income. This paper provides novel application of methodological approaches in social movement studies such as the Generalized Additive Models with smoothing functions and Synthetic Control Method to extract micro-level inferences on the relationship between economic factors and social movement formations. I gauge the implications of the main argument with a new dataset that is a composition of aggregated levels of social movements per-capita, real per-capita personal income, income inequality index, labor unemployment laws, social policy liberalization index and equal pay laws among other variables. The empirical exercises reveal that when accounting for the full range of socio-economic variables with fixed effects and instrumental variables, the dual impact of economic growth and decline on social movements is non-linear and U-shaped in the US states across time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

See the DCA website, Form list, for more details on methodology of data collection: https://web.stanford.edu/group/collectiveaction/cgi-bin/drupal/node/3.

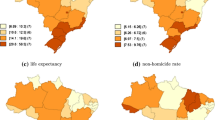

DC, Alaska, and NY are clear outliers where there were significantly higher level social movements relative to population size.

The first stage is a linear model as inclusion of the log-log regression of raw values of RPCPI, income inequality and LUC with the averages for neighboring states for these variables derived spurious predictions.

Specifically, the left side panel in the Fig. 16 for State fixed effects show that the predicted levels of RCPCI and II are highly correlated with the instrumented state general revenue variable. henceforth, I do not include that variable in the main model where state fixed effects are present.

The splines can be interpreted as polynomial functions that determine the estimation range similar to confidence intervals in linear regression.

The smooth joining of polynomial curves indicates that the second derivatives are balanced at the knots where the curves are formed on data points.

The SCM weights are estimated to enhance the similarity between the synthetic control and the treatment unit for identified matching variables. The matching is achieved by mapping the quantifiable features between the treatment and control groups within each state for the observed time period 1960–1995.

The largest gap seems to occur between the years 1979 and 1987.

Both of these variables are from the CSP dataset. Details are available in the Appendix 1: Data.

References

Abadie, A., and J. Gardeazabal. 2003. The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the Basque Country. American Economic Review 93 (1): 113–132.

Agerberg, M. 2019. The curse of knowledge? Education, corruption, and politics. Political Behavior 41 (2): 369–399.

Alesina, A., S. Özler, N. Roubini, and P. Swagel. 1996. Political instability and economic growth. Journal of Economic Growth 1 (2): 189–211.

Alexander, M.A. 2016. Application of mathematical models to English secular cycles. Cliodynamics 7: 76–108.

Almeida, P. 2019. Social movements: The structure of collective mobilization. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Amenta, E., and N. Caren. 2022. Rough draft of history: A century of US social movements in the news, vol. 197. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Amenta, E., N. Caren, E. Chiarello, and Y. Su. 2010. The political consequences of social movements. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 287–307.

Andrews, I., J.H. Stock, and L. Sun. 2019. Weak instruments in instrumental variables regression: Theory and practice. Annual Review of Economics 11: 727–753

Angrist, J.D., and A.B. Krueger. 2001. Instrumental variables and the search for identification: From supply and demand to natural experiments. Journal of Economic perspectives 15 (4): 69–85.

Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58 (2): 277–297.

Banerjee, A.V., and E. Duflo. 2003. Inequality and growth: What can the data say? Journal of Economic Growth 8 (3): 267–299.

Bapuji, H., and L. Neville. 2015. Income inequality ignored? An agenda for business and strategic organization. Strategic Organization 13 (3): 233–246.

Beck, N., and S. Jackman. 1998. Beyond linearity by default: Generalized additive models. American Journal of Political Science 42: 596–627.

Bender, A., A. Groll, and F. Scheipl. 2018. A generalized additive model approach to time-to-event analysis. Statistical Modelling 18 (3–4): 299–321.

Benford, R.D., and D.A. Snow. 2000. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639.

Bevan, S. 2013. Continuing the collective action dilemma: The survival of voluntary associations in the united states. Political Research Quarterly 66 (3): 545–558.

Blanchet, T., L. Chancel, and A. Gethin. 2022. Why is Europe more equal than the united states? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14: 480–518.

Bound, J., D.A. Jaeger, and R.M. Baker. 1995. Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association 90 (430): 443–450.

Calhoun, C. 1993. new social movements of the early nineteenth century. Social Science History 17 (3): 385–427.

Caren, N., S. Gaby, and C. Herrold. 2017. Economic breakdown and collective action. Social Problems 64 (1): 133–155.

Carreras, M., and S. Bowler. 2019. Community size, social capital, and political participation in Latin America. Political Behavior 41 (3): 723–745.

Chapman, T., and E. Reinhardt. 2013. Global credit markets, political violence, and politically sustainable risk premia. International Interactions 39 (3): 316–342.

Chenoweth, E., and J. Ulfelder. 2017. Can structural conditions explain the onset of nonviolent uprisings? Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (2): 298–324.

Cherif, R., F. Hasanov, and L. Wang. 2018. Sharp instrument: A stab at identifying the causes of economic growth. International Monetary Fund.

Cowell, F.A. (1995). Measuring inequality, (2nd Ed.). New York and Toronto, N.Y.: Simon and Schuster International, Harvester Wheatsheaf/Prentice Hall, London.

Dalton, R., A. Van Sickle, and S. Weldon. 2010. The individual-institutional nexus of protest behaviour. British Journal of Political Science 40: 51–73.

Dalton, R.J. 2017. The participation gap: Social status and political inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Della Porta, D. 2000. Social capital, beliefs in government, and political corruption. In Disaffected democracies: What’s troubling the trilateral countries 202–228, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Della Porta, D., M. Andretta, T. Fernandes, F. O’Connor, E. Romanos, and M. Vogiatzoglou. 2017. Late neoliberalism and its discontents in the economic crisis: Comparing social movements in the European periphery. Berlin: Springer.

Downs, A. 1957. An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of Political Economy 65 (2): 135–150.

Eagles, C.W. 2010. The civil rights movement in America. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Edwards, B., and P.F. Gillham. 2013. Resource mobilization theory. In The Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of social and political movements (Vol. 1). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Elmes, M.B. 2018. Economic inequality, food insecurity, and the erosion of equality of capabilities in the united states. Business & Society 57 (6): 1045–1074.

Fatke, M., and M. Freitag. 2013. Direct democracy: Protest catalyst or protest alternative? Political Behavior 35 (2): 237–260.

Ferrara, G., and F. Vidoli. 2017. Semiparametric stochastic frontier models: A generalized additive model approach. European Journal of Operational Research 258 (2): 761–777.

Fewster, R.M., S.T. Buckland, G.M. Siriwardena, S.R. Baillie, and J.D. Wilson. 2000. Analysis of population trends for farmland birds using generalized additive models. Ecology 81 (7): 1970–1984.

Frank, M. 2014. A new state-level panel of annual inequality measures over the period 1916–2005. Journal of Business Strategies 31 (1): 241–263.

Gaby, S., and N. Caren. 2016. The rise of inequality: How social movements shape discursive fields. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 21 (4): 413–429.

Gamba, A. 2009. Neighbors matter: Evidence on trade, growth and productivity. Revista Economia.

Gamson, W.A. 2004. Bystanders, public opinion, and the media. In The Blackwell companion to social movements, Vol. 1, 242–264.

Gardner, J.M. 1994. The 1990–91 recession: How bad was the labor market. Monthly Labor Review 117: 3.

Gilchrist, D., T. Emery, N. Garoupa, and R. Spruk. 2022. Synthetic control method: A tool for comparative case studies in economic history. Journal of Economic Surveys 37: 409–445.

Gobillon, L., and T. Magnac. 2016. Regional policy evaluation: Interactive fixed effects and synthetic controls. Review of Economics and Statistics 98 (3): 535–551.

Goodfriend, M., and J. McDermott. 2021. The American system of economic growth. Journal of Economic Growth 26 (1): 31–75.

Graetz, M.J., and I. Shapiro. 2020. The wolf at the door: The menace of economic insecurity and how to fight it. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Greenwood, D.T., and E.N. Wolff. 1992. Changes in wealth in the united states, 1962–1983. Journal of Population Economics 5 (4): 261–288.

Grossmann, M., M.P. Jordan, and J. McCrain. 2021. The correlates of state policy and the structure of state panel data. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 21 (4): 430–450.

Guide, A.U. 2013. Codebook for the ANES 2012 time series study. Ann Arbor and Palo Alto: The University of Michigan and Stanford University.

Guisan, A., T.C. Edwards Jr., and T. Hastie. 2002. Generalized linear and generalized additive models in studies of species distributions: Setting the scene. Ecological Modelling 157 (2–3): 89–100.

Hamilton, R.W., C. Mittal, A. Shah, D.V. Thompson, and V. Griskevicius. 2019. How financial constraints influence consumer behavior: An integrative framework. Journal of Consumer Psychology 29 (2): 285–305.

Hudik, M. 2019. Two interpretations of the rational choice theory and the relevance of behavioral critique. Rationality and Society 31 (4): 464–489.

Ives, B., and J.S. Lewis. 2020. From rallies to riots: Why some protests become violent. Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (5): 958–986.

Jenkins, J.C. 1983. Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements. Annual Review of Sociology 9: 527–553.

Jones, K., and N. Wrigley. 1995. Generalized additive models, graphical diagnostics, and logistic regression. Geographical Analysis 27 (1): 1–18.

Karavardanyan, S. 2021. Are actions costlier than words? formal models of protester-police dynamic interactions and evidence from empirical analysis. Operations Research Forum 2 (4): 1–29.

Karp, J.A., and C. Milazzo. 2015. Democratic scepticism and political participation in Europe. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 25 (1): 97–110.

Korotayev, A., S. Bilyuga, and A. Shishkina. 2018. GDP per capita and protest activity: A quantitative reanalysis. Cross-Cultural Research 52 (4): 406–440.

Korotayev, A.V., P.S. Sawyer, and D.M. Romanov. 2021. Socio-economic development and protests: A quantitative reanalysis. Comparative Sociology 20 (2): 195–222.

Kurer, T., S. Häusermann, B. Wüest, and M. Enggist. 2019. Economic grievances and political protest. European Journal of Political Research 58 (3): 866–892.

Labonte, M., G. E. Makinen, and Government Finance Division, 2002. The current economic recession: How long, how deep, and how different from the past? In Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

Langrock, R., T. Kneib, R. Glennie, and T. Michelot. 2017. Markov-switching generalized additive models. Statistics and Computing 27 (1): 259–270.

MacCulloch, R., and S. Pezzini. 2010. The roles of freedom, growth, and religion in the taste for revolution. The Journal of Law and Economics 53 (2): 329–358.

Mansour, F., T. Leonce, and F.G. Mixon. 2021. Who revolts? Income, political freedom and the Egyptian revolution. Empirical Economics 61 (3): 1135–1150.

Mazumder, S. 2018. The persistent effect of us civil rights protests on political attitudes. American Journal of Political Science 62 (4): 922–935.

McAdam, D., and S. Tarrow. 2018. The political context of social movements. In The Wiley Blackwell companion to social movements 17–42, John Wiley & Sons

Memoli, V., and M. Quaranta. 2019. Economic evaluations, economic freedom, and democratic satisfaction in Africa. The Journal of Development Studies 55 (9): 1928–1946.

Meyer, D.S. 2004. Protest and political opportunities. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 125–145.

Meyer, D.S., and S. Tarrow. 1998. A movement society: Contentious politics for a new century. In The social movement society: Contentious politics for a new century 1–28, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Miguel, E., S. Satyanath, and E. Sergenti. 2004. Economic shocks and civil conflict: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Political Economy 112 (4): 725–753.

Novak, M. 2021. Freedom in contention: Social movements and liberal political economy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Opp, K.-D. 2019. The rationality of political protest: A comparative analysis of rational choice theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

Osborne, D. 1988. Laboratories of democracy. Brighton: Harvard Business School Press.

Parvin, M. 1973. Economic determinants of political unrest: An econometric approach. Journal of Conflict Resolution 17 (2): 271–296.

Porta, D. 2008. Protest on unemployment: Forms and opportunities. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 13 (3): 277–295.

Power, S.A. 2018. The deprivation-protest paradox: How the perception of unfair economic inequality leads to civic unrest. Current Anthropology 59(6): 765–789.

Sahm, C. 2019. Direct stimulus payments to individuals. In Recession ready: Fiscal policies to stabilize the American economy 67–92.

Sapra, S.K. 2013. Generalized additive models in business and economics. International Journal of Advanced Statistics and Probability 1 (3): 64–81.

Sargan, J.D. 1958. The estimation of economic relationships using instrumental variables. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 393–415.

Shujie, M., R.J. Carroll, H. Liang, and S. Xu. 2015. Estimation and inference in generalized additive coefficient models for nonlinear interactions with high-dimensional covariates. Annals of Statistics 43 (5): 2102.

Smith, H.J., and T.F. Pettigrew. 2015. Advances in relative deprivation theory and research. Social Justice Research 28 (1): 1–6.

Snow, D., D. Cress, L. Downey, and A. Jones. 1998. Disrupting the quotidian: Reconceptualizing the relationship between breakdown and the emergence of collective action. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 3 (1): 1–22.

Snow, D.A., and S.A. Soule. 2010. A primer on social movements. New York: WW Norton.

Solt, F. 2008. Economic inequality and democratic political engagement. American Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 48–60.

Solt, F. 2015. Economic inequality and nonviolent protest. Social Science Quarterly 96 (5): 1314–1327.

Soule, S., and J. Earl. 2005. A movement society evaluated: Collective protest in the united states, 1960–1986. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 10 (3): 345–364.

Soule, S.A., and B.G. King. 2008. Competition and resource partitioning in three social movement industries. American Journal of Sociology 113 (6): 1568–1610.

Tarrow, S. 2008. Charles tilly and the practice of contentious politics. Social Movement Studies 7 (3): 225–246.

Tarrow, S. 2022. Power in movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Treisman, D. 2000. Decentralization and inflation: Commitment, collective action, or continuity? American Political Science Review 94 (4): 837–857.

Vavreck, L., and D. Rivers. 2008. The 2006 cooperative congressional election study. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 18 (4): 355–366.

Verba, S., K.L. Schlozman, and H.E. Brady. 1995. Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Waits, M.J. 2000. Economic development strategies in the American states. International Journal of Public Administration 23 (9): 1541–1571.

Walker, I., and T.F. Pettigrew. 1984. Relative deprivation theory: An overview and conceptual critique. British Journal of Social Psychology 23 (4): 301–310.

Walsh, C.E., et al. 2004. FRBSF Economic Letter, October 6, 1979.

Wang, D.J., H. Rao, and S.A. Soule. 2019. Crossing categorical boundaries: A study of diversification by social movement organizations. American Sociological Review 84 (3): 420–458.

Wasow, O. 2020. Agenda seeding: How 1960s black protests moved elites, public opinion and voting. American Political Science Review 114 (3): 638–659.

Xu, Y. 2017. Generalized synthetic control method: Causal inference with interactive fixed effects models. Political Analysis 25 (1): 57–76.

Zarnowitz, V., and G.H. Moore. 1977. The recession and recovery of 1973–1976. In Explorations in economic research, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1–87. NBER.

Funding

This research was supported by the Center for Global Peace and Conflict Studies, The Jack W. Peltason Center for the Study of Democracy, and School of Social Sciences, all from University of California, Irvine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Ethical Conduct Statement

The authors consciously assure that for the manuscript the following is fulfilled: This material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere. The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. The paper reflects the authors’ own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner. The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers. The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research. All resources used are properly disclosed (correct citation). Literally copying of text must be indicated as such by using quotation marks and giving proper reference.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Data

Correlation matrix between instrumented variables used in the second stage. Notes: V1 = Norm TCAPC, V2 = TCAPC, V3 = RPCPI (I), V4 = Income Ineq. (I), V5 = General Rev. (I), V6 = Labour Unemp. Comp. (I), V7 = Violent crime rate, V8 = Social liberalism, V9 = Social Policy Liber. The term (I) = instrument in the 1st stage

Appendix 2: Methodology

The SCM has various advantages over other empirical models used with cross-country time series longitudinal datasets. First, it allows to predict not only immediate influence of independent variable on levels in the outcome variable but also aggregate output impact for every single year for each country that is available. Second, the SCM considers the untreated observations in cross-sectional time series format by applying weighted means of other units as the counterfactuals (Gobillon and Magnac 2016). The SCM achieves this by composing control groups consisting of weighted combination of observation units (in our case countries-years) and comparing them to treatment groups which have some characteristic that is absent in the control groups (Xu 2017). Third, in contrast to DiD method and fixed or random effects techniques popular in panel data analysis that only control for time-invariant influences, the SCM allows to account for time-variant unobservable factors (Abadie and Gardeazabal 2003). Fourth, compared to system generalized method of moments and other dynamic models that permit to estimate the average effect of treatment drawing on the entire sample (Arellano and Bond 1991), the SCM enables to analyze the causal effect of regime instabilities (such as corruption and income declines) on social movement levels in temporal perspective for treatment groups within individual units (states) of our data.

In this manner, I leverage the comparative case study capability of SCM approach to enable fabricating a synthetic control group to utilize by paralleling the outcome of interest, NSMPC , in a treated unit with the results of that control group without the explicit disclosure of that control group to the intervention of interest (Gilchrist et al. 2022). Given the intuition and setup explain for Eq. (9) in “Case Studies Using Synthetic Control Method”, let’s represent the matrices of treatments and outcomes produced by those treatments with a combination of \(\textit{N} \times \textit{T}\) matrices and denote this combination by M. Hence, referring to the Eq. (9), I suggest that the outcome matrix of interest is denoted by Y given the structure of M which arrives to:

From the equation above, I consider that the influence of treatment is expressed for each period t, suggesting that it is subject to change temporally. The primary empirical task becomes the requirement to estimate \(Y_{j,t N}\) while accounting for the scenario of where the outcome is not treated. To achieve this objective, I recognize that the cluster of units in the donor pool could aggregate the features of the treated unit more precisely than the potential effect produced by units that are not treated. This property of the SCM model given the input from the donor pool establishes the method as a weighted average of the units pooled from the donor group comprising the collection of controls. Given the combination of time and units matrices M from equation 10, I have weights defined as M = \((m2,\ldots ,mjt+1)\) which encompasses the synthetic control estimate of \(Y_{j,t}^{N}\) in the following equation:

Appendix 3: Empirical Outcomes

See Figs. 17, 18, 19 and 20 and Tables 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Karavardanyan, S. Economic Development, Inequality and Dynamics of Social Movements in the United States: Theory and Quantitative Analysis. J. Quant. Econ. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-024-00383-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-024-00383-0

Keywords

- Economic development

- Growth

- Crises

- United States

- Social movements

- Synthetic control method

- Generalized additive model

- Panel data analysis