Abstract

Anxiety and depression are among the most common mental health problems in children and adolescents, and evidence-based digital programs may help in their prevention. However, existing reviews lack a detailed overview of effective program elements, including structural features and supporting content. This umbrella review synthesizes the main elements of effective, evidence-based digital programs which facilitate the prevention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Based on an analysis of 11 existing reviews that describe 45 programs, key components and content contributing to program effectiveness were identified. These included a focus on modular and linear structure, which means organizing the program in a clear and sequential manner. Additionally, approaches based on cognitive behavioral therapy and gamification to engage and motivate users, were identified as effective components. The findings provide a better understanding of what makes digital programs effective, including considerations for sustainability and content, offering valuable insights for the future development of digital programs concerning the prevention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Critically noted is that the differentiation between prevention and intervention in the program description is not always clear and this could lead to an overestimation of prevention effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global government measures and restrictions introduced in 2020 to control the spread of COVID-19, such as enforced isolation and school closures, have led to an increase in the risk of mental health problems (Wade et al., 2020). The prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents has reached 20.95% during the COVID-19 pandemic, as shown by a meta-analysis (Raccanello et al., 2023). Research had previously indicated that there has been a significant increase especially in anxiety and depression during the past years (Durbeej et al., 2019). For approximately 50% of individuals with mental disorders, the onset of the disorder falls into adolescence (Casanas et al., 2018; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003) and mental health problems in this age group may further deteriorate over the long term (e.g., Kauhanen et al., 2023). Due to their relatively elusive nature, internalizing disorders, such as anxiety and depression in children and adolescents, require special attention. As parents and friends are frequently unable to detect the existence of such problems (McGinnis et al., 2019) the resulting lack of awareness can lead to a delay in diagnosis and may thus cause significant harm and distress among the individuals affected. Efforts aimed at preventing anxiety and depression are thus of tremendous importance. The aim of this umbrella review is to synthesize key findings from current reviews of effective digital programs in the prevention and early intervention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents to highlight and emphasize their potential.

Prevention plays a pivotal role in mitigating the impact of risk factors by enabling individuals to strengthen necessary skills and foster the resources needed in managing mental health (Domschke et al., 2021; Hugh-Jones et al., 2021; Tomb & Hunter, 2004). Therefore, it is essential to focus on preventing anxiety and depression to improve individual wellbeing and reduce the social burden of mental illness among young people. As usual, prevention is seen as more promising than cure. It is cost-effective and entails less stress for those involved than dealing with illness and disorder after it has developed (Bennet et al., 2015; Gladstone & Beardslee, 2009; Hugh-Jones et al., 2021).

Digital programs have been identified as one possible tool in the prevention and early intervention of mental health problems in children and adolescents. Such programs have a relatively wide reach and tend to be more flexible and accessible than traditional face-to-face treatment (Bergin et al., 2020). Although there is a plethora of programs and an extensive body of research systematically analyzing their effectiveness (e.g., Campisi et al., 2022; Das et al., 2016), such research remains relatively disjointed and difficult to survey. Therefore, it is important to pay special attention to the key components of such programs, including intervention type, mode of delivery, availability, structural features, and content in order to identify potential patterns of effectiveness and best practice. These can then be used in guiding recommendations and support for future program development.

Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents

Current research indicates that mental health challenges among children and adolescents have increased significantly. In particular, internalizing disorders such as anxiety and depression have become widespread during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dale et al., 2023). Studies investigating depressive symptoms during the pandemic have reported alarming prevalence rates ranging from 23 to 64% (Dale et al., 2023; Samji et al., 2022; Theberath et al., 2022). Pooled estimates indicate that globally, 25% of young people are currently experiencing symptoms of depression, while 20% are experiencing symptoms of anxiety (Racine et al., 2021).

Anxiety and depression are characterized by disruptions in emotions and moods that are directed inwardly. Consequently, they may be challenging for others to recognize (Danneel et al., 2020). Anxiety disorders can manifest in various forms among children and adolescents. Their characteristics vary considerably, as does their age of onset. The common characteristic of many forms of anxiety is that it leads to a high level of physiological arousal in a very short time, causing intense stress for the affected children (APA, 2022).

Depression in children and adolescents is also a complex condition and is not to be equated with the typical experience of a low mood or occasional sadness. It cannot be controlled through the mere exercise of willpower or effort (Essau, 2007) and it is accompanied by a marked lack of motivation and energy. Such emotional states may be typical responses to specific circumstances, such as loss, failure, or disappointment. However, a certain level of symptom stability over time and associated functional impairment are critical factors in identifying the presence of a clinically significant depressive disorder (Essau, 2007). Similar to anxiety, depression is categorized as an internalizing disorder and both occur together very frequently (APA, 2012). According to DSM-5-TR (APA, 2012), depression can be categorized into three principal disorders: major depressive disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, and persistent depressive disorder (APA, 2012). In the absence of effective coping strategies, anxiety and depression can have substantial and long-lasting effects on the well-being of children and adolescents. These effects can impact their social-emotional and academic functioning even beyond their transition into adulthood (APA, 2012; Beames et al., 2021; Donovan & Spence, 2000; Klicpera et al., 2019).

Differentiation of Types of Prevention Targeting Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents

Basically, prevention can be differentiated in three approaches regarding the aim it is seeking to achieve (Commission on Chronic Illness, 1957). Primary prevention aims to reduce the incidence of a disorder by lowering the likelihood of new cases. Secondary prevention aims to lower the prevalence of a disorder by reducing the rate of established cases. Tertiary prevention aims to decrease the amount of disability and maladjustment associated with a disorder (Ogden & Hagen, 2019). This classification scheme was expanded by Gordon in 1987, adding a risk-benefit perspective. This allows for further differentiation between universal, selective, and indicated prevention (Ogden & Hagen, 2019). Universal prevention aims to prevent or delay the occurrence of a disorder for an entire population, selective prevention targets groups of individuals at risk of developing a disorder, while indicated prevention focuses on individuals who already exhibit early signs of a disorder (Ogden & Hagen, 2019).

Thus, prevention aims to foster well-being and to reduce the occurrence or development of illness, symptoms, problems, or maladjustments. In contrast, intervention involves treatment or other actions taken after such illnesses have already developed. The goal of intervention is to alleviate or reduce these issues (Ogden & Hagen, 2019). However, the application of conventional public health classification systems, such as primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, and Gordon’s differentiation in universal, selective, and indicated prevention, faces challenges and appears to be not so clear in the field of mental health (Institute of Medicine, 1994). The complexity arises from the fact that symptoms and dysfunctions may occur even when not all diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder are met, blurring the distinction between prevention and treatment (Institute of Medicine, et al., 1994). Furthermore, it may occur that individuals may not be receptive to an intervention program but could be engaged in prevention programs that teach preventive topics and coping strategies.

The prevention of anxiety and depression has been recognized internationally as a public health priority (Bennet et al., 2015; Hugh-Jones et al., 2021; WHO, 2019; UNICEF & WHO, 2022) and various prevention programs have been developed. These programs are based on the same body of evidence as intervention programs and aim to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms, strengthen stress management skills, promote problem-solving skills and relaxation techniques, and train social skills (Klicpera et al., 2019; Schulte-Körne & Schiller, 2012).

Program Characteristics

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an important component of mental health programs. CBT is a comprehensive and dynamic approach that has been developed and utilized for a wide range of mental health issues and is widely used for the prevention and early intervention/treatment of anxiety and depression. CBT utilizes the interrelation between cognition and emotions in order to change negative feelings. The primary goal of CBT is to reassess and change cognitive and thinking processes, target symptoms, reduce distress, and promote positive behavioral responses (Leichsenring et al., 2006). In addition to CBT, only relatively few further types of intervention have been explored to the same extend as CBT. Although some alternative methods have been attempted in various cases (e.g., psychoanalytic therapy, self-expression through play), the large body of evidence suggests that CBT is quite successful in treating anxiety and depression. CBT-based interventions are therefore widely used and have been shown to be beneficial not only for individuals at risk but also for the general population of adolescents (e.g., Schneider, 2014; Ye et al., 2014).

One of the most well-known programs, the Coping Cat program, introduced by Philipp Kendall (1994), can be considered a pioneering CBT intervention for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. The evidence for its effectiveness is impressive (Schneider, 2014). It is a 16-week school-based program and has four components: (1) recognizing anxiety and its physical signs, (2) identifying and labeling emotions in anxiety-provoking situations, (3) learning coping strategies (e.g., self-talk, problem-solving and relaxation) and (4) practicing self-praise for progress (Schneider, 2014). Previous research shows that the development of coping mechanisms is of tremendous importance, as anxious children tend to automatically resort to avoidance, which is an unfavorable strategy in the long term (Klicpera et al., 2019; Scaini et al., 2016; Schulte-Körne & Schiller, 2012; Warwick et al., 2017). When symptoms are clearly present, elements of behavioral therapy for symptom-oriented anxiety reduction (e.g., relaxation training, desensitization, exposure training) have been proven to be most effective (Klicpera et al., 2019; Scaini et al., 2016). For example, to gradually confront anxiety-provoking situations, participants are encouraged to create an exposure hierarchy, starting with mildly anxiety-provoking situations, and progressing to highly anxiety-provoking situations (Schneider, 2014). This enables participants to gradually become accustomed to and thus overcome anxiety-inducing situations in a controlled manner. Additionally, guided visual imagery can be used to prepare for exposure (Schneider, 2014).

CBT is also the most widely used and best studied type of intervention for depression prevention and typically involves a standardized, protocol-based approach (Williams & Crandal, 2015). In particular, the improvement of various forms of distorted thinking is enforced in CBT-oriented programs for the prevention of depression in adolescents (Schneider, 2014). This means that cognitive restructuring is a central component (e.g., learning how to identify and correct negative or irrational thoughts) (Schneider, 2014). Additionally, the promotion of coping, problem-solving, social and communication skills, psychoeducation, assertiveness training and relaxation training may be considered the most useful components of preventive interventions. Although interpersonal psychotherapy tradition (IPT) has not yet been as extensively evaluated as CBT-oriented programs, this approach, which focuses on interpersonal relationship problems, also seems promising (Bernaras et al., 2019; Garber, 2006; Gladstone & Beardslee, 2009; Hetrick et al., 2015; Klicpera et al., 2019; Schneider, 2014). Since effective prevention of anxiety shares many components with effective prevention of depression, e.g., positive thinking, stress management, cognitive problem solving, enhancing social skills etc., it seems useful to combine prevention programs for these two disorders.

Digital Programs

Children and adolescents often prefer digital technologies and enjoy using them. Thus, well-designed digital programs tailored to the target population can promote the application of specific skills and strategies in children’s and adolescents’ daily lives. Such programs are conducive to encouraging engagement by the target group (Lucas-Thompson et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2010). Moreover, digital programs serve a dual purpose of providing support and raising awareness among children and adolescents about mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. Through psychoeducational content, these platforms can provide valuable information and resources, helping young individuals understand and navigate the complexities of their mental health (Bevan Jones et al., 2018; Lucas-Thompson et al., 2019). Digital programs offer a significant advantage in terms of accessibility (Ashford et al., 2016), allowing young people to seek help or engage in self-help activities at their convenience. Such flexibility is particularly critical, given that only a small percentage of young people with mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, have access to, or receive in-person/face-to-face treatment (Grist et al., 2019; Reyes-Portillo et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2010). Moreover, these programs can be adaptable to individual needs and self-directed. Digital programs also provide the advantage of anonymity. Adolescents, who are often hesitant to seek support due to stigma or privacy concerns, can maintain confidentiality through digital programs (Murray, 2012).

Despite the advantages, studies indicate that the majority of available online programs require user registration and/or payment, vary significantly in length and number of modules, and lack public research evidence of intervention efficacy, making it difficult to identify appropriate programs (Ashford et al., 2016). Nevertheless, initial systematic reviews have confirmed the effectiveness of digital mental health interventions for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents (Calear & Christensen, 2010; Grist et al., 2019; Hollis et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2023). Similarly, Buttazoni et al. (2021) found small but significant effects when investigating smartphone-based interventions for internalizing disorders in adolescents. Studies investigating Serious Games have reported promising results (Fleming et al., 2014), but limited to depression-focused programs, excluding anxiety (Townsend et al., 2022). It has also been emphasized that, similar to offline programs, cognitive-behavioral programs can be effective in adolescents, but only a few exhibit good acceptance and sustainability (Carnevale, 2013), consequently limiting their widespread availability (Grist et al., 2019).

Programs for the prevention and early intervention of anxiety and depression in young individuals can be effective, but the active ingredients of these programs remain unclear (Beames et al., 2021). Based on these findings, there is a consensus that more comprehensive research is needed to identify the conditions for the efficacy of digital programs for the prevention and intervention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents (Calear & Christensen, 2010).

Current Study

While various studies have examined the efficacy of digital programs in fostering mental health as well as addressing anxiety and depression in children and adolescents, a comprehensive, detailed, and structured summary of the key components and detailed information about the structural features and content that determine their effectiveness is still lacking. This study aims to bridge this gap by outlining evidence-based digital programs for the prevention and early intervention of anxiety and depression in childhood and adolescence, in order to derive recommendations for future program development. Thus, the first aim is to investigate which digital evidence-based programs are effective in combatting anxiety and depression in childhood and adolescence. The second aim is to systematically examine specific components of these effective programs. Important features are the type of intervention, age or target group, mode of delivery, availability, and possibility of access, as well as structural features and the predominant content.

Methods

In order to obtain a suitable overview of existing effective digital programs for the prevention and early intervention of anxiety and/or depression in children and adolescents, an umbrella review was conducted. Through the umbrella review, it was possible to combine the results of existing studies narratively. An umbrella review is a systematic method of reviewing secondary research to provide an overall picture of the findings related to a specific phenomenon (Aromataris et al., 2015; Grant & Booth, 2009).

Search Strategy

The literature search in the present study followed a systematic approach and used the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). The primary search was conducted in November–December 2022 using the electronic databases PubMed, Cochrane, PsycInfo, PsycArticles and, in addition, using the University Library Search Tool, the databases Scopus, Web of Science, ProQuest, Springer Online Journals, ScienceDirect Journals and Wiley were used. The databases were selected on the basis of their relevance and coverage of psychological, educational, and preventive interventions. Table 1 lists the search strings used for each database. The aim was to find (systematic) reviews of digital programs for the prevention/intervention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Based on the results of the primary search, effective (preventive) intervention programs were identified (Table 5) and then summarized (in a structured spreadsheet). Subsequently, the corresponding studies of the identified programs were examined and an additional search was conducted (January–March 2023) to obtain more detailed information on the intervention type, age/target group addressed, mode of delivery, availability and access, structural features, and content of the effective programs.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) for the primary search were determined with regard to the target group, publication type and intervention type in order to ensure evidence-based results. Systematic reviews and reviews were included if they described the effectiveness of digital/online prevention/intervention programs for anxiety and/or depression in children and adolescents aged 11 to 18 years. Although the World Health Organization (WHO, 1986) recommends that individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 should be considered adolescents, in most countries, those who reach the age of 18 are considered adults. Furthermore, in most countries, children move on to the next level of schooling at the age of 11, which is also a particularly vulnerable transition period (Mackenzie et al., 2012). Therefore, the age range selection for this study is 11–18. As many reviews targeted individuals aged 15–24 years, which is consistent with the developmental psychological perspective that assumes that the period of adolescence is extending (Slater & Bremner, 2003), exceptions were made if the reported results were identifiable for the age group of interest and were reported appropriately, or if the pooled mean age of the meta-analysis fell within the age range of interest.

Reviews were excluded, if they were aimed at adults or targeted a clinical sample, if they did not address the prevention or early intervention of depression and/or anxiety, if the publication type was not a (systematic) review, and if they were not written in English. The restriction to publications in English is due to the fact that English is the most widely used language in the scientific community. This restriction may help to make the results more internationally relevant, and it can enhance the comparability of studies by ensuring a clear and consistent explanation of the methodology and results of the included articles. Restrictions to one language also increase the efficiency of the review process as fewer translations are needed. Reviews published before 2000 were not included in order to avoid the risk of relying on outdated or unavailable technologies. On the basis of these criteria, articles were selected or eliminated for further investigation.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The Rayyan QCRI application was used for collaborative selection of articles (Ouzzani et al., 2016), which provides a streamlined platform for systematic review article selection. This web and mobile tool allows multiple reviewers to access articles independently and blinded, ensuring transparency and consensus in the screening process (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Two reviewers independently and blinded screened and assessed the articles. Unanimous agreement between authors was required for an article to be included. For data extraction, summarizing and analyzing a structured template spreadsheet was used. Extracted data included: authors, year of publication, article type, studies/interventions included in analysis, intervention types, outcomes, and key findings. Results were collated into additional structured template spreadsheets and synthesized into written summaries. The lead author analyzed the results of the articles with a focus on identifying effective digital/online programs for anxiety and depression for the interested age group and listed them in a separate spreadsheet, which was reviewed by a second reviewer. For the purpose of this article, preventive and early interventions were defined as any planned intervention or program that was undertaken with the aim of improving mental health conditions or modifying its determinants. Only those programs that were identified as effective based on at least one review from the primary search, addressed anxiety and/or depression and were developed for children and adolescents in the age category of interest (11–18) were included. In a next step, the programs were analyzed in detail with a special focus on the main categories: intervention type, age/target group, mode of delivery, availability and access, structural features (e.g. following a modular/session-based, linear/self-directed order, etc.), and content. If some information (the structure or content of the program) was not elaborated in the respective identified reviews, an additional search of the program was conducted (January–March 2023) to collect all necessary information. Within this additional search it was also checked whether the programs were still available/online and accessible.

Results

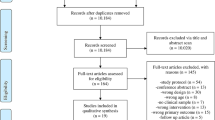

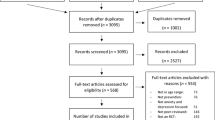

In the primary search (November–December 2022) a total of 758 articles met the search criteria and were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final sample consisted of 11 articles. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021) of the search history and the selection process. The additional search (January–March 2023) concerning program details and specifics resulted in screening and analyzing 71 articles describing the identified 45 programs.

Article Characteristics

Table 5 (Appendix 1) summarizes the main characteristics of the articles included based on the primary search (n = 11) and provides information on authors, publication year, article type, number of studies/interventions analyzed, program intervention types, outcome measures, the identified effective programs for the interested age group (11–18), and key findings on the effectiveness of the programs. 55% (n = 6) of the articles included were systematic reviews, 27% (n = 3) were systematic reviews with meta-analyses and 18% (n = 2) were (exploratory) reviews. Of the 11 articles included, 36% (n = 4) were published between 2020 and 2022 and 64% (n = 7) between 2011 and 2019. All the included articles (n = 11) were published in peer-reviewed journals, reported methods and data sources meeting the methodological quality standards and reported no conflicts of interest on the part of the authors. A total of 291 studies were assessed and included in the narrative synthesis of the 11 articles reviewed. 82% (n = 9) of the articles addressed mental health interventions for both anxiety and depression. One article (Rice et al., 2014) only addressed depression and one (Tozzi, et al., 2018) only addressed anxiety. Since not all reviews conducted a meta-analysis, the findings on program effectiveness and relevant factors of influence are presented in a narrative summary. A brief synopsis of the findings and evidence found in the articles is also provided in order to highlight the most important aspects.

Positive outcomes were consistently reported for digital CBT-oriented programs, and no differences in effect sizes were found when compared with traditional (offline) CBT interventions. There were fewer reports of effectiveness for anxiety than for depression. There were mixed results regarding the selection of the target group (universal vs. indicated): In some studies, no differences were found in the effectiveness of programs when they were implemented universally or selectively. However, the “MoodGym” program was found to be more effective when implemented as a universal program. One article also found that indicated/targeted interventions showed larger effect sizes for depression (Siemer et al., 2011).

In terms of the design and usability of the programs, it became quite clear that the following components were crucial for the adherence and acceptance by the target group: Gamification programs were highly regarded (Garrido et al., 2019), psychoeducational content had to be kept as short and relatable as possible (Gilbey et al., 2020), and homework-like experiences were rated negatively (Gilbey et al., 2020). Multimedia-rich programs were also found to be more appropriate for children and adolescents from low socio-economic and educational backgrounds (Kuosmanen et al., 2019).

With regard to supervision by others (e.g., mental health professionals or teachers), it was shown that supervision or the implementation in a school setting resulted in larger effect sizes (Garrido et al., 2019; Kuosmanen et al., 2019) than those found in a leisure-based setting with no supervision. In contrast to this, one review showed that the program with the lowest level of interactivity in the program had the largest effect sizes (Siemer et al., 2011).

Program Characteristics

Table 3 lists the 45 effective prevention intervention programs identified via the systematic analysis of the review articles included (n = 11) and provides an overview of the primary mental health conditions addressed, as well as of the intervention type/the (therapeutic) approach followed in the programs. To enhance readability, the identified programs are cited numerically according to Table 3 in the following. References to program-related studies are provided as examples. A detailed list of the studies associated with the programs can be found in Table 6 (Appendix 2). The majority of programs (1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 26, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40) were developed in Australia and New Zealand (n = 16; 36%), eleven programs (24%) in the United States (11, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 32, 36, 44), five programs (11%) were each developed in the Netherlands(2, 4, 21, 28, 29) and the United Kingdom(7, 9, 24, 41, 42), three programs ( 7%) were developed in Canada (27, 30, 43), two (4%) in China(15, 25) and one (2%) each in Israel(13), Chile(31) and Ireland(45).

Mental Health Conditions

While effectiveness in relation to anxiety and depression was examined in all programs, not all programs focused primarily on these two mental health domains or had these constructs as their primary topic. 22% (n = 10) of the programs focused on both the mental health domains of depression and anxiety(7, 9, 11, 12, 17, 19, 21, 28, 38, 43); 44% (n = 20) focused specifically on depression(1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 14, 18, 22, 23, 25, 30, 31, 33, 34, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44, 45), 9% (n = 4) focused specifically on anxiety (5, 8, 24, 32). In addition, five programs(6, 13, 15, 27, 29) had their main focus on general mental health, (11%), and additional individual programs focusing on specific topics such as suicide prevention(20), suicide, depression & anxiety(40), loneliness & depression(36), stress(16), distress(26) and eating disorders & depression(35).

Intervention Type

Given the strong evidence for the widespread successful use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions for the prevention of internalized disorders (Rice et al., 2014), the most commonly used intervention type was CBT (65%/n = 29)(1–10, 14, 15, 17–19, 23–25, 31–33, 35–38, 40–43). Two programs employed problem solving therapy (PST)(28,44), and two programs provided psycho-educational content only(16, 27). There were also individual programs covering each of the following approaches: positive psychology(12), therapeutic blogging(13), motivational interviewing(20), emotional working memory(21), referral to care(22), mindfulness(26), chat support(29), spiritual health (30), emotional self-awareness(34), moderated online social therapy (MOST)(39), peer support(45), and acceptance & commitment therapy(11).

Age/Target Group

As the programs targeted children and adolescents of different age groups, a categorization (8–18 years) was made on the basis of the minimum age of the sample used to evaluate each program. As can be seen in Fig. 2, more than half of the programs (55.6%; n = 25) were developed for children and adolescents with a minimum age of 12–14 years(1,2, 3, 6, 8,9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 42). For 15.6% (n = 7) of the programs, no categorization could be made owing to the lack of specific sample information(11, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 32). It was only stated that the target population included undergraduate students, young adults or students, i.e., those who belong to the upper age group of the target group of interest in the present study (18 years old).

Program Structure/Design

Mode of Delivery

The majority of 62% (n = 28) of the programs was delivered online via a website(1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 35, 39, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45) and 13% (n = 6) via an app(3, 9, 26, 32, 36, 37). 11% (n = 5) of the programs required a mobile phone (e.g., messenger services)(6, 22, 33, 34, 38), 9% (n = 4) were delivered via CD-ROM(7, 8, 10, 42) and two programs (4%) via social media(15, 27).

Availability and Access

To obtain information on the availability of the programs at the time of the analysis for this article, an additional search was carried out using Google, based on the information provided in the associated studies. At the time of the synthesis undertaken for this study (March 2023), 69% (n = 31) of the programs were not available/could not be found. Three programs(1, 12, 26) were available without any limitations, six programs (13%) were only available in certain countries/languages, and five programs (11%) were only available with the invitation/support of a (mental) health practitioner/professional.

Structural Features

73% of the programs (n = 33) followed a modular/session-based structure(1–5, 7− 11, 14–19, 21, 23–25, 28, 30, 32–44). The number of modules ranged from 2(11) to 14(2). As can be seen in Fig. 3, most modular programs had between 6 and 8 modules.

Like educational programs, intervention programs can be structured in either a linear or self-directed way. In self-directed learning, learners structure their own learning path. In contrast, linear structuring provides a predetermined, logical structure for learners to follow (Crick et al., 2014). In this sample, 65% (n = 29) of the programs followed a linear structure(1–5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14–17, 19, 21, 23, 24, 28, 31–34, 37, 38, 40–44) and 31% (n = 14) were designed to be self-directed by the users(6, 8, 12, 13, 18, 20, 22, 26, 27, 29, 30, 36, 39, 45).

Program Content

CBT Elements

As mentioned above, most of the programs followed a CBT-oriented approach. In order to categorically elicit the CBT elements of the programs for the purposes of this umbrella review, the checklist for CBT components by Oud et al. (2019) was used. This checklist distinguishes between four pillars: psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and relaxation. Table 6 (Appendix 2) provides an extensive and comprehensive summary of the content of the programs and the CBT elements they contain, including details of the general structure (i.e., modular and/or session-based), duration, delivery method, and references to any relevant studies that have examined the programs.

36% (n = 16) of the programs addressed all four categories of CBT elements, 20% (n = 9) addressed three categories, 22% (n = 10) addressed two categories and 4% (n = 2) addressed only one category—psychoeducation. 18% of the programs (n = 8) either did not include any CBT components, or these could not be identified from the information available. Of the programs specifically designed for the prevention/intervention of depression, 15 (75%) followed the CBT approach. The others used approaches such as referral to care(22), spiritual health(30), emotional self-awareness(34), problem solving(44) and peer support(45). All four programs that were specifically designed for the prevention/intervention of anxiety(5,8,24,32) followed the CBT approach and included two to four CBT components. The specific content of the programs is outlined in the following sections. This information was extracted from the respective program articles included in the sample of this umbrella review. To aid understanding, an overview of the main content techniques is given in Table 4.

Content Addressing Depression

Out of the 20 programs that explicitly target depression, the narrative analysis showed that eight of them provided psychoeducational content about depression (3,4,14,18,37,39,42,45) and four programs provided information about CBT(3,10,18,37). In addition, six programs emphasized that their content specifically addressed the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behavior(1,3,4,10,33,37). 80% of the programs (n = 16)(1,2,3,4,10,14,18,25,30,31,33,37,39,41,42,44) taught strategies for identifying and changing dysfunctional/negative thoughts. 50% of the programs included mood monitoring features(3,4,10,14,18,22,34,37,41,42), and nine programs taught strategies for raising awareness of and planning pleasant activities (1,3,4,10,14,18,30,33,37). Another important topic was the introduction of relaxation techniques, which, according to the information available, was an integral part of seven programs(1,3,10,30,37,39,41). Relapse prevention skills, such as identifying relapse risk situations (covering both internal and external experiences) or documenting potential negative feelings and strategies for dealing with them, were also included in the content of five programs(3,4,10,37,42).

Six of the programs(2,25,30,33,41,42) used narrative teen stories/vignettes to convey the content, and four programs used characters to present the main topics(1,3,14,37). Four programs(14,33,42,44) used video testimonials (e.g., teen actors, peers, national celebrities) to deliver content to the users (e.g., psychoeducational content, own experience with depressive). Four of the programs featured user avatars that progressed through a story-driven game and completed specific tasks/missions (3,10,23,37). Two other programs were also based on a storyline(31,33) but did not include user avatars.

Content Addressing Anxiety

All programs that focused specifically on anxiety included graded exposure techniques as part of their content(5,8,24,32). Three programs provided psychoeducational content about anxiety and CBT(5,8,32); two programs explained the relationship between feelings, thoughts, and behavior and included relaxation techniques in their content(5,24). Cognitive restructuring was part of two programs(5,8), goal setting was addressed in three programs(5,8,24) and one program provided assessment/monitoring of anxiety symptoms(32). Two programs(5,8) also included content regarding relapse prevention.

Due to the large number of depression programs identified, comparing programs for depression and anxiety was quite challenging. However, one notable finding is that case vignettes and testimonials were used less frequently in programs for anxiety. Only one program used case studies of adolescents which were presented as a video (8) and another program used testimonials to deliver the content (24).

Discussion

Mental health problems in children and adolescents are a growing concern. Specifically, anxiety and depression are the most commonly reported mental health problems in this age group, with significant increases in prevalence rates compared to the pre-pandemic period (Dale et al., 2023; Racine et al., 2021; Samji et al., 2022; Theberath et al., 2022). These findings highlight the urgent need for preventive interventions to address mental health challenges faced by young people. Preventive interventions can reduce risk factors and support mental health. Digital interventions have emerged as a potential means of reaching a wider population and of providing accessible and effective support. This article recognizes the importance of developing and implementing digital prevention programs that not only target existing mental health problems, but also focus on prevention and early intervention. To ensure that these programs are accessible and effective for youth (Grist et al., 2019), it is important to have knowledge of the active ingredients of effective digital prevention programs (Beames et al., 2021; Calear & Christensen, 2010). Thus, the aim of this study was to identify effective digital prevention programs for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents, and to examine their structural and content characteristics. The method used included a systematic umbrella review to provide an overview of existing evidence-based programs. The inclusion criteria were stringent, focusing on systematic reviews and reviews published between 2000 and 2022 that evaluated the effectiveness of digital prevention/intervention programs for anxiety and/or depression in children and adolescents.

Eleven articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria, describing a total of 45 effective digital prevention and/or intervention programs. A narrative analysis was conducted to examine the characteristics of these programs, covering the mental health conditions addressed, intervention types, target groups, as well as program structure and content. It became evident that it is difficult to establish a clear distinction between prevention programs and intervention/treatment programs. The dividing line between these two program types is often blurred (Institute of Medicine, 1994). Some of the identified programs served both preventive and interventive/treatment purposes, despite the search criteria clearly excluding clinical samples. However, prevention and intervention programs are often rooted in the same theoretical foundations, and in the field of mental health, it is not uncommon for symptoms to be present without clinical significance or formal diagnosis. Therefore, both preventive and interventional measures can be viable and relevant to the general population. Having said that, the results indicate that selective/targeted programs and those that specifically addressed anxiety or depression as their primary purpose were found to be more effective than those that targeted a variety of psychological outcomes. While this may, to some extent, be due to the higher level of symptoms among those initially targeted, it still seems important that specific content be tailored to match the needs of children and adolescents in order to increase the effectiveness of the program. For this purpose, implemented screening procedures identifying those at risk, or mood monitoring procedures, can contribute to a rule-based allocation of individual modules/activities and thus deliver targeted content to users.

The programs covered in this umbrella review varied in terms of their target age group, but the majority focused on children and adolescents with a minimum age of 12–14 years. The programs were predominantly delivered online via websites or apps. This approach provides ease of accessibility and flexibility for users (Ashford et al., 2016; Grist et al., 2019; Murray, 2012; Reyes-Portillo et al., 2014; Richardson, 2010). Unfortunately, a significant number of the identified programs were no longer available or accessible by the time the analysis was undertaken, which is in line with prior findings (Ashford et al., 2016; Carnevale, 2013; Grist et al., 2019). Therefore, it is essential to consider program sustainability and maintenance both during and after program development. Failure to do so could result in the loss of valuable, evidence-based and effective programs. There is a clear need for sustained availability, ongoing adaptation to new systems, and continuous support of digital interventions to ensure their long-term impact and benefits for the target population. It is crucial to regularly adapt digital programs to new technical requirements to avoid wasting the extensive effort put into their development. It is also essential to ensure the continuity of digital programs, even after the completion of underlying research projects. Developers should carefully consider the viability and continued presence of these programs.

Based on the findings regarding program structure and specifics, it is recommended to use a modular, linear, multimodal approach that incorporates elements of gamification. This is because the majority of the programs followed a modular/session-based structure with a linear or self-directed learning approach. Gamification elements, narrative stories and avatars were used to engage users and enhance their experience. The findings highlight the importance of considering factors such as program interactivity, supervision and multimedia-rich content to improve engagement and acceptability (Lucas-Thompson et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2010). In order to take account of the specific preferences of the target group, it is strongly recommended that psychoeducational content and information be kept as brief and concise as possible.

It is also recommended that CBT should be recognized as a powerful theoretical framework. As was found in previous research (e.g., Ye et al., 2014; Schneider, 2014; Williams & Crandall, 2015), the majority of programs used a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach. CBT interventions were found to be effective in reducing symptoms and promoting positive behavioral responses. Nonetheless, individual programs based on concepts derived from interpersonal therapy, positive psychology, mindfulness, social therapy, and acceptance & commitment therapy were also found to be effective. What all programs had in common, however, was that they included at least some elements of CBT.

The programs’ content analysis revealed the inclusion of various CBT elements, such as psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and relaxation techniques. Most programs included psychoeducational and informational content about CBT (if the program was based on it). According to the analyzed reviews’ results, psychoeducational and informational components should be kept as short and relatable as possible in order to maintain high adherence. Furthermore, explaining and understanding the connection between thoughts, feelings and behavior should be considered a fundamental component of the content for anxiety and depression. Many activities build on this knowledge to enable a more advanced understanding of mental health support, and exercises are better internalized or transferred to everyday life.

The analysis indicated that when developing digital prevention programs, it is important to consider several factors beyond the inclusion of CBT elements, such as the inclusion of mood monitoring activities. It was found that about half of the effective programs included some kind of mood monitoring activities, such as a daily assessment of mood using a predetermined scale. While strategies for identifying and changing negative/dysfunctional thoughts seem to be crucial in programs for depression, teaching graded exposure techniques seems to be highly relevant in programs for anxiety. In addition, content on relaxation procedures/relaxation techniques also seems to be important. As already mentioned in the section “Study characteristics”, gamification-oriented programs can have a positive impact on user adherence and acceptance. This was shown in the effective programs by the fact that there were both fully game-based or storyline-driven programs, and that the majority used gamification elements (quizzes, animations, action tasks, missions, audio/video).

When interpreting the results, it is important to consider the limitations of this study. The search was conducted using specific databases, so there may be relevant reviews or programs that were not included in this umbrella review. Additionally, it is worth noting the temporal limitation, as only programs examined until December 2022 were included. The limited availability of programs posed a challenge, as a significant proportion of the identified programs were no longer accessible in detail, preventing a complete mapping of the programs. Nevertheless, important content and design features of digital programs for the prevention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents could still be identified based on the available study articles and reviews.

Conclusion

In light of the pressing increase in mental health issues in children and adolescents, there is a clear need for tailored and effective programs for their prevention. Despite various studies on the effectiveness of digital prevention programs for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents, there is no synthesis of the active components that contribute to their effectiveness. This umbrella review aims to address this gap by conducting a systematic and detailed review of effective evidence-based digital programs for the prevention of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents, summarizing their structural features and content. The results demonstrate that utilizing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) within a modular, linear, and multimodal approach, along with gamification elements significantly improves user engagement and acceptability. Additionally, it is recommended to implement specific content elements relating to the disorder addressed, i.e., mood monitoring activities, negative thought identification and modification strategies for depression, graded exposure techniques, and relaxation content for anxiety. However, it is important not only to consider these specific content components in future development processes, but also emphasize the sustainability and continuity of the programs to ensure that they can be offered over the long term, equipping young people with the necessary skills and resources they need to proactively manage their mental health.

Data availability

All data collected for this study were obtained from published peer-review literature. Data extracted to inform this umbrella review are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Abeles, P., Verduyn, C., Robinson, A., Smith, P., Yule, W., & Proudfoot, J. (2009). Computerized CBT for adolescent depression (“Stressbusters”) and its initial evaluation through an extended case series. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465808005067

American Psychiatric Association. (2012). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Anstiss, D., & Davies, A. (2015). ‘Reach Out, Rise Up’: The efficacy of text messaging in an intervention package for anxiety and depression severity in young people. Children and Youth Services Review, 58, 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.011

Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C. M., Holly, C., Khalil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 132–140.

Ashford, M. T., Olander, E. K., & Ayers, S. (2016). Finding web-based anxiety interventions on the world wide web: A scoping review. JMIR Mental Health, 3(2), e14. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5349

Attwood, M., Meadows, S., Stallard, P., & Richardson, T. (2012). Universal and targeted computerized cognitive behavioral therapy (Think, Feel, Do) for emotional health in schools: Results from two exploratory studies. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(3), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00627.x

Beames, J. R., Kikas, K., & Werner-Seidler, A. (2021). Prevention and early intervention of depression in young people: An integrated narrative review of affective awareness and Ecological Momentary Assessment. In BMC Psychology, 9, 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00614-6

Bennett, K., Manassis, K., Duda, S., Bagnell, A., Bernstein, G. A., Garland, E. J., Miller, L. D., Newton, A., Thabane, L., & Wilansky, P. (2015). Preventing child and adolescent anxiety disorders: overview of systematic reviews. Depression and Anxiety, 32(12), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22400

Bergin, A. D., Vallejos, E. P., Davies, E. B., Daley, D., Ford, T., Harold, G., Hetrick, S., Kidner, M., Long, Y., Merry, S., Morriss, R., Sayal, K., Sonuga-Barke, E., Robinson, J., Torous, J., & Hollis, C. (2020). Preventive digital mental health interventions for children and young people: A review of the design and reporting of research. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3, 133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00339-7

Bernaras, E., Jaureguizar, J., & Garaigordobil, M. (2019). Child and adolescent depression: A review of theories, evaluation instruments, prevention programs, and treatments. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 543. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00543

Bevan Jones, R., Thapar, A., Stone, Z., Thapar, A., Jones, I., Smith, D., & Simpson, S. (2018). Psychoeducational interventions in adolescent depression: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(5), 804–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.015

Bobier, C., Stasiak, K., Mountford, H., Merry, S., & Moor, S. (2013). When ‘e’ therapy enters the hospital: examination of the feasibility and acceptability of SPARX (a cCBT programme) in an adolescent inpatient unit. Advances in Mental Health, 11(3), 286–92. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.2013.11.3.286

Boniel-Nissim, M., & Barak, A. (2013). The therapeutic value of adolescents’ blogging about social-emotional difficulties. Psychological Services, 10(3), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026664

Bradley, K. L., Robinson, L. M., & Brannen, C. L. (2012). Adolescent help-seeking for psychological distress, depression, and anxiety using an Internet program. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 14(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2012.665337

Braithwaite, S. R., & Fincham, F. D. (2007). ePREP: Computer based prevention of relationship dysfunction, depression and anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(5), 609–622. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.5.609

Bruehlman-Senecal, E., Hook, C. J., Pfeifer, J. H., FitzGerald, C., Davis, B., Delucchi, K. L., Haritatos, J., & Ramo, D. E. (2020). Smartphone app to adress loneliness among college students: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 7(10), e21496. https://doi.org/10.2196/21496

Burckhardt, R., Manicavasagar, V., Batterham, P. J., Miller, L. M., Talbot, E., & Lum, A. (2015). A web-based adolescent positive psychology program in schools: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(7), e187. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4329

Buttazoni, A., Brar, K., & Minaker, L. (2021). Smartphone-based interventions and internalizing disorders in youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e16490. https://doi.org/10.2196/16490

Calear, A. L., & Christensen, H. (2010). Review of internet-based prevention and treatment programs for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Medical Journal of Australia. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03686.x

Calear, A. L., Christensen, H., Mackinnion, A., & Griffiths, K. M. (2013). Adherence to the MoodGYM program: Outcomes and predictors for an adolescent school-based population. Journal of Affective Disorder, 147(1–3), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.036

Calear, A. L., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A., Griffiths, K. M., & O’Kearney, R. (2009). The YouthMood Project: A cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1021–1032. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017391

Campisi, S., Ataullahjan, A., Baxter, J.-A., Szatmari, P., & Bhutta, Z. (2022). Mental health interventions in adolescence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 48, 101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101492

Carnevale, T. D. (2013). Universal adolescent depression prevention programs: A review. In Journal of School Nursing, 29(3), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840512469231

Carrasco, A. E. (2016). Acceptability of an adventure video game in the treatment of female adolescents with symptoms of depression. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcomes, 19(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2016.182

Casañas, Rocío, Arfuch, Victoria-Mailen., Castellví, Pere, Gil, Juan-José., Torres, Maria, Pujol, Angela, Castells, Gemma, Teixidó, Mercè, San-Emeterio, Maria Teresa, Sampietro, Hernán María., Caussa, Aleix, Alonso, Jordi, & Lalucat-Jo, Lluís. (2018). “EspaiJove.net”-a school-based intervention programme to promote mental health and eradicate stigma in the adolescent population: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5855-1

Chapman, R., Loades, M., O’Reilly, G., Coyle, D., Patterson, M., & Salkovskis, P. (2016). ‘Pesky gNATs’: investigating the feasibility of a novel computerized CBT intervention for adolescents with anxiety and/or depression in a Tier 3 CAMHS setting. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 9, e35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X16000222

Chen, R. Y., Feltes, Y. R., Tzeng, W. S., Lu, Z. Y., Pan, M., Zhao, N., Talkin, R., Javaherian, K., Glowinski, A., & Ross, W. (2017). Phone-based interventions in adolescent psychiatry: A perspective and proof of concept pilot study with a focus on depression and autism. JMIR Res Protoc, 6(6), e114. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.7245

Christensen, H., Griffiths, K. M., & Korten, A. (2002). Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: Analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 4(1), e3. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4.1.e3

Clark, D. A. (2013). Cognitive restructuring. In S. G. Hofmann (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118528563.wbcbt02

Clarke, A., Kuosmanen, T., & Barry, M. (2015). A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 90–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0165-0

Clarke, G., Kelleher, C., Hornbrook, M., Debar, L., Dickerson, J., & Gullion, C. (2009). Randomized effectiveness trial of an Internet, pure self-help, cognitive behavioral intervention for depressive symptoms in young adults. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(4), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070802675353

Commission on Chronic Illness. (1957). Chronic illness in the United States (Vol. 1). Harvard University Press.

Cook, L., Mostazir, M., & Watkins, E. (2019). Reducing stress and preventing depression (RESPOND): Randomized controlled trial of web-based rumination-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for high-ruminating university students. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(5), e11349. https://doi.org/10.2196/11349

Coyle, D., McGlade, N., Doherty, G., & O’Reilly, G. (2011). Exploratory evaluations of a computer game supporting cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979378

Crick, R. D., Stringher, C., & Ren, K. (2014). Learning to learn. Taylor & Francis.

Cunningham, M. J., Wuthrich, V. M., Rapee, R. M., Lyneham, H. J., Schniering, C. A., & Hudson, J. L. (2009). The Cool Teens CD-ROM for anxiety disorders in adolescents: A pilot case series. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(2), 125–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-0703-y

Dale, R., Jesser, A., Pieh, C., O’Rourke, T., Probst, T., & Humer, E. (2023). Mental health burden of high school students, and suggestions for psychosocial support, 1.5 years into the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 1015–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02032-4

Danneel, S., Geukens, F., Maes, M., Bastin, M., Bijttebier, P., Colpin, H., Verschueren, K., & Goossens, L. (2020). Loneliness, social anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Longitudinal distinctiveness and correlated change. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(11), 2246–2264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01315-w

Das, J., Salam, R., Lassi, Z., Khan, M., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. (2016). Interventions for adolescent mental health: An overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

De Voogd, E. L., Wiers, R. W., Zwitser, R. J., & Salemink, E. (2016). Emotional working memory training as an online intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Australian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12134

Domschke, K., Schiele, M. A., & Romanos, M. (2021). Prävention von Angsterkrankungen [prevention of anxiety disorders]. Der Nervenarzt, 92, 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-020-01045-1

Donovan, C. L., & Spence, S. H. (2000). Prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(4), 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00040-9

Dubad, M., Winsper, C., Meyer, C., Livanou, M., & Marwaha, S. (2018). A systematic review of the psychometric properties, usability and clinical impacts of mobile mood-monitoring applications in young people. Psychological Medicine, 48(2), 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717001659

Durbeej, N., Sörman, K., Norén Selinus, E., Lundsträm, S., Lichtenstein, P., Hellner, C., & Halldner, L. (2019). Trends in childhood and adolescent internalizing symptoms: Results from Swedish population based twin cohorts. BMC Psychol, 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0326-8

Essau, C.A. (2007). Depression bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. 2. Aufl. UTB.

Fleming, T. M., Cheek, C., Merry, S. N., Thabrew, H., Bridgman, H., Stasiak, K., Shepherd, M., Perry, Y., & Hetrick, S. (2014). Serious games for the treatment or prevention of depression: A systematic review. Revista De Psicopatologia y Psicologia Clinica, 19(3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.19.num.3.2014.13904

Flett, J. A., Conner, T. S., Riordan, B. C., Patterson, T., & Hayne, H. (2020). App-based minfulness meditation for psychological distress and adjustment to college in incoming university students: A pragmatic, randomized, waitlist-controlled trial. Psychology & Health, 35(9), 1049–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1711089

Foa, E. B. & Kozak, M. J. (1985). Treatment of anxiety disorders: Implications for psychopathology. In: A. H. Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders, pp. 421–452.

Fukkink, R. G., & Hermanns, J. (2009). Children’s experiences with chat support and telephone support. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(6), 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02024.x

Garber, J. (2006). Depression in children and adolescents: Linking risk research and prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(6 Suppl 1), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.007

Garrido, S., Millington, Ch., Cheers, D., Boydell, K., Schubert, E., Meade, T., & Nguyen, Q. (2019). What works and what doesn’t work? A systematic review of digital mental health interventions for depression and anxiety in young people. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 759. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00759

Gerrits, R. S., van der Zanden, R. A. P., Visscher, R. F. M., & Conijn, B. P. (2007). Master your mood online: A preventive chat group intervention for adolescents. Australian E-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 6(3), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.6.3.152

Gilbey, D., Morgan, H., Lin, A., & Perry, Y. (2020). Effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of digital health Interventions for LGBTIQ+ young people: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(12), e20158. https://doi.org/10.2196/20158

Gladstone, T. R., & Beardslee, W. R. (2009). The prevention of depression in children and adolescents: a review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 54(4), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400402

Grant, M., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Grist, R., Croker, A., Denne, M., & Stallard, P. (2019). Technology delivered interventions for depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0271-8

Heinicke, B. E., Paxton, S. J., McLean, S. A., & Wertheim, E. H. (2007). Internet-delivered targeted group intervention for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9097-9

Hetrick, S. E., Cox, G. R., & Merry, S. N. (2015). Where to go from here? An exploratory meta-analysis of the most promising approaches to depression prevention programs for children and adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(5), 4758–4795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120504758

Hetrick, S. E., Yuen, H. P., Bailey, E., Cox, G. R., Templer, K., Rice, S. M., Bendall, S., & Robinson, J. (2017). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for young people with suicide-related behaviour (Reframe-IT): A randomized controlled trial. BMJ Mental Health, 20(3), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102719

Hoek, W., Schuumans, J., Koot, H. M., & Cuijpers, P. (2012). Effects of internet-based guided self-help problem-solving therapy for adolescents with depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 7(8), e43485. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043485

Hollis, C., Falconer, C., Martin, J., Whittington, C., Stockton, S., Glazebrook, C., & Davies, E. (2017). Annual research review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems—a systematic and meta-review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 474–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12663

Horgan, A., McCarthy, G., & Sweeney, J. (2013). An Evaluation of an online peer support forum for university students with depressive symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(2), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2012.12.005

Hugh-Jones, S., Beckett, S., Tumelty, E., & Mallikarjun, P. (2021). Indicated prevention interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents: A review and meta-analysis of school-based programs. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(6), 849–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01564-x

Institute of Medicine. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. National Academies Press.

Ip, P., Chim, D., Chan, K. L., Li, T. M., Ho, F. K., Van Voorhees, B. W., Tiwari, A., Tsang, A., Chan, C. W., Ho, M., Tso, W., & Wong, W. H. (2016). Effectiveness of a culturally attuned Internet-based depression prevention program for Chinese adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Depression and Anxiety, 33(12), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22554

Kauer, S. D., Reid, S. C., Crooke, A. H. D., Khor, A., Hearps, S. J. C., Jorm, A. F., Sanci, L., & Patton, G. (2012). Self-monitoring using mobile phones in the early stages of adolescent depression: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), e67. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1858

Kauhanen, Laura, Yunus, Wan Mohd Azam Wan Mohd., Lempinen, Lotta, Peltonen, Kirsi, Gyllenberg, David, Mishina, Kaisa, Gilbert, Sonja, Bastola, Kalpana, Brown, June S. L., & Sourander, Andre. (2023). A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 995–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02060-0

Kendall, P. (1994). Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(1), 100–110.

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., & Poulton, R. (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinalcohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(7), 709–717. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709

King, C. A., Eisenberg, D., Zheng, K., Czyz, E., Kramer, A., Horwitz, A., & Chermack, S. (2015). Online suicide risk screening and intervention with college students: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 630–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038805

Klicpera, C., Gasteiger-Klicpera, B., & Bešić, E. (2019). Psychische Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter [mental disorders in childhood and adolescence]. utb GmbH.

Kuosmanen, T., Clarke, A., & Barry, M. (2019). Promoting adolescents’ mental health and wellbeing: Evidence synthesis. Journal of Public Mental Health, 18(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-07-2018-0036

Leech, T., Dorsten, D., Taylor, A., & Li, W. (2021). Mental health apps for adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Children and Youth Services Review, 127, 106073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106073

Leichsenring, F., Hiller, W., Wiessberg, M., & Leibing, E. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy: Techniques, efficacy, and indications. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 60(3), 233–259. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2006.60.3.233

Levin, M. E., Pistorello, J., Seeley, J. R., & Hayes, S. C. (2014). Feasibility of a prototype web-based acceptance and commitment therapy prevention program for college students. Journal of American College Health, 62(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.843533

Lewinsohn, P. M., & Graf, M. (1973). Pleasant activities and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41(2), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035142

Li, T., Chau, M., Wong, P., Lai, E., & Yip, P. (2013). Evaluation of a web-based social network electronic game in enhancing mental health literacy for young people. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(5), e80. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2316

Lillevoll, K. R., Vangberg, H. C. B., Griffiths, K. M., Waterloo, K., & Eisemann, M. R. (2014). Uptake and adherence of a self-directed internet-based mental health intervention with tailored e-mail reminders in senior high schools in Norway. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-14

Lintvedt, O. K., Griffiths, K. M., Sørensen, K., Østvik, A. R., Wang, C. E., Eisemann, M., & Waterloo, K. (2013). Evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of unguided internet-based self-help intervention for the prevention of depression: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(1), 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.770

Livingston, J. D., Tugwell, A., Korf-Uzan, K., Cianfrone, M., & Coniglio, C. (2013). Evaluation of a campaign to improve awareness and attitudes of young people towards mental health issues. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(6), 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0617-3

Lucassen, M. F. G., Hatcher, S., Fleming, Th., Stasiak, K., Shepherd, M. J., & Merry, S. N. (2015b). A qualitative study of sexual minority young people’s experiences of computerised therapy for depression. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(3), 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215579542

Lucassen, M. F. G., Merry, S. N., Hatcher, S., & Frampton, Ch. M. A. (2015a). Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.12.008

Lucas-Thompson, R. G., Broderick, P. C., Coatsworth, J. D., & Smyth, J. M. (2019). New avenues for promoting mindfulness in adolescence using mHealth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(1), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1256-4

MacDonell, K., & Prinz, R. (2016). A review of technology-based youth and family-focused interventions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20, 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-016-0218-x

Mackenzie, E., McMaugh, A., & O’Sullivan, K. (2012). Perceptions of primary to secondary school transitions: Challenge or threat? Issues in Educational Research, 22(3), 298–314.

Makarushka, M. M. (2011). Efficacy of an Internet-based intervention targeted to adolescents with subthreshold depression. Doctoral Thesis, University of Oregon Graduate School.

Manicavasagar, V., Horswood, D., Burckhardt, R., Lum, A., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Parker, G. (2014). Feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based positive psychology program for youth mental health: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(6), e140. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3176

March, S., Spence, S. H., & Donovan, C. L. (2009). The efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(5), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn099

McGinnis, R. S., McGinnis, E. W., Hruschak, J., Lopez-Duran, N. L., Fitzgerald, K., Rosenblum, K. L., & Muzik, M. (2019). Rapid detection of internalizing diagnosis in young children enabled by wearable sensors and machine learning. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210267

Melnyk, B. M., Amaya, M., Szalacha, L. A., Hoying, J., Taylor, T., & Bowersox, K. (2015). Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of the COPE online cognitive-behavioral skill-building program on mental health outcomes and academic performance in freshmen college students: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(3), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12119

Merry, S. N., Stasiak, K., Shepherd, M., Framptom, C., Fleming, T., & Lucassen, M. F. G. (2012). The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerised self help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ, 344, e2598. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2598

Murray, E. (2012). Web-based interventions for behavior change and self-management: Potential, pitfalls, and progress 2.0. Medicine, 1(2), e3. https://doi.org/10.2196/med20.1741

Neil, A., Batterham, P., Christensen, H., Bennett, K., & Griffiths, K. (2009). Predictors of adherence by adolescents to a cognitive behavior therapy website in school and community-based settings. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(1), e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1050

Noh, D., & Kim, H. (2022). Effectiveness of online interventions for the universal and selective prevention of mental health problems among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prevention Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01443-8

Ogden, T., & Hagen, K. A. (2019). Adolescent mental health. Prevention and intervention (2nd ed.). Routledge.

O’Kearney, R., Gibson, M., Christensen, H., & Griffiths, K. M. (2006). Effects of a cognitive-behavioural internet program on depression, vulnerability to depression and stigma in adolescent males: A school-based controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 35(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070500303456

O’Kearney, R., Kang, K., Christensen, H., & Griffiths, K. (2009). A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depression and Anxiety, 26(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20507

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Federowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, St., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pinto, M. D., Greenblatt, A. M., Hickman, R. L., Rice, H. M., Thomas, T. L., & Clochesy, J. M. (2015). Assessing the critical parameters of eSMART-MH: A promising avatar-based digital therapeutic intervention to reduce depressive symptoms. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 52(3), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12112

Raccanello, D., Rocca, E., Vicentini, G., & Brondino, M. (2023). Eighteen months of COVID-19 pandemic through the lenses of self or others: A meta-analysis on children and adolescents’ mental health. Child and Youth Care Forum, 52, 737–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-022-09706-9

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Reid, S. C., Kauer, S. D., Hearps, S. J. C., Crooke, A. H. D., Khor, A. S., Sanci, A. L., & Patton, G. C. (2011). A mobile phone application for the assessment and management of youth mental health problems in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Family Practice, 12, 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-131

Reid, S. C., Kauer, S. D., Hearps, S. J. C., Crooke, A. H. D., Khor, A. S., Sanci, L. A., & Patton, G. C. (2013). A mobile phone application for the assessment and management of youth mental health problems in primary care: Health service outcomes from a randomised controlled trial of mobiletype. BMC Family Practice, 14, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-84

Ren, Z., Li, X., Zhao, L., Yu, X., Li, Z., Lai, L., Ruan, Y., & Jiang, G. (2016). Effectiveness and mechanism of internet-based self-help intervention for depression: The Chinese version of MoodGYM. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(7), 818–832. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00818

Reyes-Portillo, J. A., Mufson, L., Greenhill, L. L., Gould, M. S., Fisher, P. W., Tarlow, N., & Rynn, M. A. (2014). Web-based interventions for youth internalizing problems: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(12), 1254-1270.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.005

Rice, S., Gleeson, J., Davey, C., Hetrick, S., Parker, A., Lederman, R., Wadley, G., Murray, G., Herrman, H., Chambers, R., Russon, P., Miles, C., D’Alfonso, S., Thurley, M., Chinnery, G., Gilbertson, T., Eleftheriadis, D., Barlow, E., Cagliarini, D., … Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2016). Moderated online social therapy for depression relapse prevention in young people: Pilot study of a ‘next generation’ online intervention. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(4), 613–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12354