Abstract

There is a need for a systematic understanding of how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) affect peer relationships during adolescence and the subsequent effects on youth well-being. This study conducted a systematic literature review of the two decades (1999–2019) following the CDC-Kaiser ACE study (1998). The review included 11 ACEs (i.e., 10 ACEs from the CDC-Kaiser ACE study plus child welfare involvement) and searched five databases (i.e., Embase, ERIC, PsycINFO, PTSDpubs, and PubMed). Ninety-two studies were included. The findings indicated that ACEs were differentially associated with six aspects of peer relationships: (1) ACEs were negatively associated with peer relation quantity and peer status; (2) ACEs were not significantly related to peer support; (3) associations of ACEs with peer relationship quality and peer characteristics included negative and nonsignificant findings; and (4) relations between ACEs and peer influence appeared contradictory (i.e., positive and negative associations). Additionally, various aspects of peer relationships further affected the well-being of youth with ACEs. The findings call for more attention to the associations between ACEs and adolescent peer relationships. Longitudinal studies that examine change over time, potential mechanisms, and moderating factors in the associations between ACEs and peer relations are needed to clarify the heterogeneity of findings across the six aspects of peer relations. Lastly, the findings suggest a potential expansion of the trauma-informed care principle by considering multiple facets of peer relationships beyond peer support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peer relationships are an important developmental context during adolescence (Bukowski et al., 2018); however, their association with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is complex and not fully understood. While there is evidence regarding the negative impacts of some ACEs on youth’s peer relationships (e.g., Gladstone et al., 2011; Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002; Kunz, 2001), it remains unclear whether this extends to all 10 ACEs as examined in the US CDC-Kaiser ACE study (Felitti et al., 1998). Further, various ACEs (e.g., threat- vs. deprivation-related ACEs) may have distinct implications for peer relations (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002; McLaughlin et al., 2014), while different aspects of peer relations, like peer relation quality versus quantity, may be differentially affected by ACEs (DeLuca et al., 2018; Negriff et al., 2015). However, no systematic reviews have synthesized the associations of all 10 ACEs with various aspects of peer relationships. In addition, it is unclear how peer relationships further affect the well-being of youth with various ACEs, although research indicates peers are an important developmental context for adolescents in general (Bukowski et al., 2018) and that peer relationships moderate the effect of some ACEs on youth development (Zielinski & Bradshaw, 2006). This study aims to fill these gaps by synthesizing two decades of research after the CDC-Kaiser ACE study, examining the complex interplay between multiple ACEs and different aspects of peer relationships as well as the role of peer relationships in the well-being of youth with ACEs.

ACEs are negative events during childhood and adolescence that potentially cause trauma, encompassing experiences like abuse, neglect, and parental mental health issues. Recent data from a 2023 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) underscore the high prevalence of ACEs, indicating that approximately 64% of individuals in the US reported experiencing at least one ACE, and 1 in 6 reported at least four ACEs before age 18 (CDC, 2023). The lasting impact of such early adversity can manifest across multiple domains of well-being, affecting physical health (e.g., heart disease, cancer, and obesity), mental health, substance abuse, and life opportunities (e.g., education, employment, and income), to name a few (Hughes et al., 2017; Metzler et al., 2017). ACEs have become widely recognized since the landmark CDC-Kaiser ACE study (Felitti et al., 1998). This seminal study investigated 10 specific ACEs, including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; emotional and physical neglect; domestic violence exposure; caregiver substance misuse; household mental illness; parental separation or divorce; and parental incarceration (Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998). ACEs in this review encompass not only the cumulative score of these 10 ACEs but also their individual and combined instances. Further, child welfare involvement (e.g., foster care, child protective service investigation) was considered an additional ACE, given the high prevalence of ACEs among this population (Turneya & Wildeman, 2017) and the existing studies on peer relationships in the context of child welfare involvement without measuring or analyzing a specific ACE as defined in the CDC-Kaiser ACE study. For example, Leslie et al. (2010) found that affiliating with deviant peers was associated with increased health-risk behaviors among youth under investigation for neglect and abuse. Including such studies allowed this review to capture a broader range of literature.

During adolescence, peer relationships become increasingly salient as adolescents spend more time with peers (Roisman et al., 2004). Adolescent peer relations are multifaceted, and scholars have examined several aspects of peer relationships, such as peer status, peer influence, peer relation quality, peer relation quantity, and peer support (e.g., Bukowski et al., 2018; Colarossi & Eccles, 2000; DeLuca et al., 2018). Peer relations have lasting implications for adolescent adjustment in the general population, influencing multiple domains like psychosocial adjustment, academic achievement, and internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Bukowski et al., 2018). Thus, it is plausible that peer relations may play an important role in the well-being of youth with ACEs (e.g., Levendosky et al., 2002; Zielinski & Bradshaw, 2006). In fact, peer relationships may exacerbate or mitigate the negative impact of specific ACEs, such as abuse and neglect, on youth development (Zielinski & Bradshaw, 2006).

In a clinical context, peers are recognized as an essential “community” for adolescents’ trauma recovery process (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). Peer support, specifically, is endorsed as one of the six principles of trauma-informed care (TIC). SAMSHA states, “Peer support and mutual self-help are key vehicles for establishing safety and hope, building trust, enhancing collaboration, and utilizing their stories and lived experience to promote recovery and healing” (SAMSHA, 2014, p. 11). Peer support within this framework is often the only peer-related component in trauma interventions for youth and refers to support from peers who have experienced the same trauma rather than all of an adolescent’s broader network of peers and friends. Further, this TIC principle does not encompass aspects of peer relationships beyond peer support (e.g., peer status, peer relation quantity).

Despite the potential role of peers in supporting youth with ACEs, reviews and meta-analyses across the last two decades indicate that youth’s traumatic experiences or ACEs may adversely impact peer relationships. For instance, in a traditional review examining the developmental trajectories of children who experienced neglect (i.e., one type of ACEs), Hildyard and Wolfe (2002) found that youth who experienced neglect tended to withdraw from peer interactions and had lower peer status. In a thematic review exploring children’s experiences of their parents’ mental illness (i.e., another ACE), Gladstone et al. (2011) found that these children were relatively isolated from peers as perceived by the parents, contrasting with the children’s reports of supportive, albeit complex, friendships. Further, a meta-analysis by Kunz (2001) examined the interpersonal relationships (i.e., peers, parents, and siblings) of children whose parents were divorced and reported a negative association between parental divorce and children’s peer relationships with youth ages 13 to 17 showing the most pronounced negative association (i.e., largest effect size) compared to other age ranges. Although these efforts aid in understanding the links between ACEs and youth peer relations, they often examine peer relationships as one component within a broader set of developmental outcomes related to ACEs and do not examine distinct aspects of peer relations. Further, no review to date has systematically synthesized all 10 ACEs as defined in the CDC-Kaiser ACE study (Felitti et al., 1998) with regard to various aspects of peer relations during adolescence, although it has been two decades since the original CDC-Kaiser ACE study was published.

Previous research indicates ACEs may have differential associations with various peer relationship aspects (DeLuca et al., 2018; Negriff et al., 2015). For instance, a meta-analysis by DeLuca et al. (2018) reported that adoption (a form of childhood adversity) was associated with lower peer relation quantity but not related to peer relation quality. Similarly, Negriff et al. (2015) found that maltreatment was associated with having fewer friends but unrelated to the youth’s perception of friend support (Negriff et al., 2015). Further, regarding a specific aspect of peer relationship (e.g., peer relation quantity), different ACEs might have differential implications. For instance, the dimensional model of adversity and psychopathology (McLaughlin et al., 2014) classifies ACEs into threat- and deprivation-related ACE categories. Hildyard and Wolfe (2002) found that neglected children (i.e., deprivation-related ACE) were more likely to have limited peer interactions than abused children (i.e., threat-related ACE). Given these complexities, a systematic review of the literature examining the associations between all 10 ACEs defined in the CDC-Kaiser ACE study and various aspects of peer relationships among adolescents is needed. The current review seeks to clarify the existing literature on the associations between multiple ACEs and peer relationship aspects while identifying areas that warrant further investigation. The synthesis aims to offer a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the literature and improve prior approaches that generalized findings from studies focusing exclusively on individual ACEs and specific aspects of peer relationships.

According to the social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), parents act as direct socializing agents that guide children’s social behaviors and attitudes, and family-based adverse experiences have implications for adolescent peer relationships. For instance, a child who grows up witnessing domestic violence may learn through modeling that aggression is a viable strategy and, in turn, use it in peer interactions (Kitzmann et al., 2003; McCloskey & Lichter, 2003). Moreover, the social-ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) posits that the mesosystem, which includes interactions between microsystems (e.g., family and peers), influences an individual’s development. Consequently, ACEs occurring within the family context may create cascading effects on adolescents’ peer relationships, leading to subsequent implications for adolescents’ well-being across multiple domains. It is critical to understand such links, as peers are an essential developmental context for adolescents (Bukowski et al., 2018).

Current Study

Despite two decades since the landmark CDC-Kaiser ACE study and the existing literature on the association between some ACEs and aspects of peer relationships, no systematic review has synthesized the associations of all 10 ACEs with multiple aspects of peer relationships. There is also a lack of comprehensive understanding of how various aspects of peer relationships subsequently influence the well-being of youth with ACEs. Thus, the primary aim of this review was to synthesize the literature regarding the associations between adolescents’ exposure to ACEs and different aspects of peer relationships (e.g., quality, quantity). Specifically, this review addressed two research questions. Does the association between ACEs and peer relations differ (i.e., positive, negative, no association) across various aspects of peer relations (Research Question 1)? Within a given peer relationship aspect, does the association between ACEs and peer relations differ across the ACEs (Research Question 2)? Prior research suggests the associations between ACEs and peer relationships might differ across peer relation aspects and ACEs. This review also synthesized the literature on the implications of various peer relationship aspects for the well-being of youth with ACEs.

Methods

Literature Search

The search was conducted in five databases: Embase (September 24, 2019), ERIC (September 30, 2019), PsycINFO (September 30, 2019), PTSDpubs (September 30, 2019), and PubMed (October 13, 2019). Search terms included three categories: ACEs (e.g., “abuse”), peer relations (e.g., “peer relation”), and age range (e.g., “adolescence”; see Supplemental Appendices A and B), which were combined by the Boolean operator AND. The qualifier [All Fields] or its equivalent (e.g., [All Text] in PsycINFO) was utilized in all five databases, except PubMed, in which the qualifier [Mesh] was added on top of [All Fields] when relevant (see Supplemental Appendix B). Two limiters were utilized: (1) the publication was in English, and (2) the year of publication was between 1999 and 2019.

Screening and Extraction

References were uploaded to DistillerSR (Version 2.39.0), a software designed for systematic reviews, for screening and data extraction. The first author completed the title screening. Abstract and full-text screenings were conducted in pairs of two independent reviewers. The research team met weekly to discuss questions that emerged. Each reviewer achieved 80% inter-rater agreement with the first author on practice data before starting the screening tasks. The inter-rater agreement ranged from 81% to 95% across the 11 weeks of abstract screening, and 83% to 92% across the 8 weeks of full-text screening. Conflicts were resolved at the end of each screening phase by discussion between each pair of reviewers, and a third reviewer was involved when necessary. When a consensus could not be reached, the team erred on the side of inclusion. The first two authors each extracted data from half of the studies and verified the data extracted by the other researcher. Discrepancies were resolved weekly.

Eleven singular ACEs were included (i.e., 10 ACEs in the CDC-Kaiser ACE study and child welfare involvement). The ACE definition in this review was slightly modified compared to the CDC-Kaiser ACE study by expanding “mother treated violently” to include other domestic violence (e.g., fathers treated violently, and no specification of the domestic violence victims). To keep the language consistent (see Fig. 1), maltreatment meant any combination of abuse (i.e., sexual, physical, emotional) and neglect (i.e., physical, emotional). Household dysfunction referred to any combination of the following five ACEs: witnessing domestic violence, caregiver substance misuse, household mental illness, parental divorce and separation, and parental incarceration. Any combination of ACEs from the maltreatment and household dysfunction groups was considered composite ACEs. Family violence referred to the combination of witnessing domestic violence and experiencing abuse.

Additionally, this review focused on ACEs perpetrated by or related to caregivers, except sexual abuse. Thus, ACEs not caused by or related to caregivers (e.g., community violence, historical trauma, sibling substance misuse) did not meet the inclusion criteria for ACEs. In the case of sexual abuse, studies often did not specify who the perpetrators were. Thus, all studies were included unless they specified it was sexual victimization perpetrated by peers.

Abstract screening (see Supplemental Appendix C for protocol) utilized the following inclusion criteria: (1) empirical research; (2) ACEs were studied during birth through adolescence; (3) peer relations were studied during adolescence; and (4) the study examined an association between ACEs and peer relations, with peer relations investigated as a dependent variable or as a moderator in the association between ACEs and another youth outcome. No screening criteria were set for investigating peer relations as a mediator (or indirect effect) because all the mediation analyses were captured by the criterion on the association between ACEs and peer relations.

During the full-text screening (see Supplemental Appendix D for protocol), the following criteria were added in addition to those utilized in abstract screening: (1) English full-text; (2) publication in peer-reviewed journals; and (3) quantitative research. Additionally, a cut-off range for adolescence was set (10 years 0 months to 19 years 11 months; World Health Organization, n.d.). Peer relationships and moderated youth outcomes had to be measured during 10–19 years for studies to be included.

During data extraction, the definition of caregiver substance misuse was aligned better with its definition in the CDC-Kaiser ACE study by only including studies that indicate problematic caregiver substance use. In addition, studies that only reported a bivariate correlation between ACEs and peer relations were excluded. The p-value of 0.05 was used to evaluate the significance. The following data were extracted for each reference: authors, year, study country, research aims, sample characteristics, research design, data analyses, ACE measures, peer relation measures, and key findings (see Supplemental Table S1). A few references were considered “marginal” cases (i.e., the reviewers did not reach a consensus regarding whether a study met all of the inclusion criteria or not) and were included to reduce the potential risk of bias due to missing data (see Supplemental Appendix E).

Quality Assessment

A 14-item checklist was utilized (Kmet et al., 2004) to assess the quality of the included studies. Three items (i.e., blinding of investigators and subjects; random allocation) were irrelevant to the review and excluded. Each item was rated as Yes (2), Partial (1), No (0), or N/A. The possible score range for each reference was 0–100%, with a higher score indicating better quality in general. The first two authors independently rated each study and discussed discrepancies to determine a final rating, and 100% agreement was reached.

Data Synthesis

No restrictions were imposed on the definition of “aspect” regarding peer relations. Instead, studies were included if they examined any aspect of peer relationships. The researchers then utilized thematic analysis to synthesize and consolidate prominent themes (or “aspects”) of peer relationships across studies (Goagoses & Koglin, 2020). The first two authors critically reflected on their own preconceptions regarding ACE and peer relationship literature (Braun & Clarke, 2023), coded and discussed such “aspects” throughout the data extraction phase, and further consolidated these aspects upon the completion of data extraction. Some aspects were deductive and had been expected prior to the search (e.g., peer relationship quantity and quality; DeLuca et al., 2018), whereas others were inductive and emerged from the articles (e.g., disclosure confidant as a unique form of peer support). Of note, certain studies included more than one aspect of peer relations and, as a consequence, are described in multiple sections within the results section. For instance, the findings of Cochran et al. (2018) are described across four peer relation sections (i.e., peer quantity, peer quality, peer characteristics, and peer status). The synthesis of the results was organized according to the following six peer relationships aspects:

-

1.

Peer relationship quantity, or the number of friends or close friends, including adolescents’ self-perceptions and the number of friendship nominations sent or received.

-

2.

Peer relationship quality, including general quality, satisfaction, intimacy, warmth, closeness, empathy, and attachment, as well as stress, conflict, and problems with friends.

-

3.

Peer characteristics, including any outcomes or features of peers affiliated with adolescents. This included both negative (e.g., deviant peer affiliation) and positive (e.g., prosocial peer affiliation) peer characteristics.

-

4.

Peer support, including youth’s self-perceptions that friends were generally supportive, perceived emotional and instrumental peer support, or perceived relative importance of peers in one’s social support system compared to other people.

-

5.

Peer influence, including peer pressure to perform specific actions, peer attitudes supporting certain behaviors, youth engaging in certain behaviors to gain peer approval, and sensitivity to peer influence.

-

6.

Peer status, including social preference and sociometric status (e.g., peer popularity, acceptance, rejection, centrality, and how liked a child was by classmates).

Results

Study Inclusion

The results of inclusion and exclusion at various phases are described in a PRISMA chart (see Fig. 2; Page et al., 2021). Studies were excluded for not meeting one (or more) of the inclusion criteria. Overall, the search yielded 47,241 records. The following number of records were retained respectively after de-duplicating, title screening, abstract screening, and full-text screening: 33,536, 4,805, 736, and 216. The full texts of the remaining 216 records were closely read, with data extracted from 140 records and 76 papers further excluded. The 140 records fell into two distinct groups in terms of peer relations: (1) general peer relationships (n = 92); and (2) bullying (n = 51). This paper reports the 92 records on general peer relationships. The records on bullying are reported in Merrin et al. (2023). Several of the 92 studies were based on the same large public datasets (e.g., National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health [Add Health], National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being [NSCAW], Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect [LONGSCAN]; see Supplemental Appendix F for more details).

PRISMA flowchart. aFour of the articles examined models that included bullying and general peer relationship (PR) variables in the same model, with bullying as the dependent variable and general PR as either a mediator or moderator. bReferences in this group examined separate models for bullying and general PR variables in relation to ACEs. As such, these three references are reported in both this manuscript and Merrin et al. (2023)

Study Characteristics

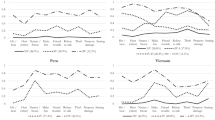

An overview of the study characteristics of the 92 included studies is provided in Table 1 (see Supplemental Table S1 for more information). There was an increase in publications in recent years (e.g., 57% were published in 2014 or later; see Fig. 3). Most studies were conducted in the US (n = 50). Studies were also conducted in other countries, including Canada (n = 7), South Korea (n = 5), the UK (n = 5), Sweden (n = 4), Brazil (n = 2), Finland (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), Israel (n = 2), and Norway (n = 2). One study was conducted in each of the following countries or regions: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Denmark, France, Haiti, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, and The Netherlands. Lastly, one study was conducted across four European countries (Austria, Germany, Slovenia, and Spain). Across the 11 singular and five combined ACEs (see Fig. 4), sexual abuse was most studied in relation to peer relations (n = 21), followed by physical abuse (n = 16), divorce and separation (n = 14), and child welfare involvement (n = 14). The other ACEs all had fewer than 10 studies.

Number of publications per year included in this review. The number of publications for 2019, 2020, and 2021 is an underestimate of the actual publications that would have met all inclusion criteria because the search was implemented in September and October of 2019. There are some publications for 2020 and 2021 because some of the publications (i.e., advance online publications) were updated with volume (issue) and page numbers and publication years by the journals after the search had been implemented. For example, Yoon et al. (2021) was published online in 2018 and was included in the search

Number of studies per ACE that examined ACE in relation to peer relationships. ACE adverse childhood experience. ACEs in uppercase indicate studies that analyzed combined ACEs (i.e., a score of more than one singular ACE) in relation to peer relationships. For instance, LeBoeuf et al. (2017) examined girls’ abuse history (either physical or emotional), thus was counted in the ABUSE group. Some studies analyzed more than one ACE score, thus were counted more than once. For example, Lim and Lee (2017) analyzed abuse and neglect as two separate ACEs, thus was counted in both the ABUSE and NEGLECT groups. The numbers in this figure include studies on the associations between ACEs and peer relationships, as well as the mediating, moderating, and risk and protective effects of peer relationships

The total score of the quality assessment ranged from 0.50 to 0.95 across studies, with an average of 0.78. Some studies received a high score due to their high quality. Others received a high score because their designs were simple, and several assessment items were not applicable. Readers are encouraged to examine the quality score at the item level (see Table 2) and consider the quality score in combination with the study design. The scores for items ranged from 0.89 (outcome measure) to 1.99 (study objective).

Study Results

Results are described according to the six aspects of peer relationships. In each aspect, analyses are reported in the following sequence (when relevant): (1) associations between ACEs and peer relation variables (i.e., main effect); (2) peer relations as a mediator in the associations between ACEs and youth outcomes (or indirect effect for cross-sectional studies); (3) peer relations as a moderator of the associations between ACEs and youth outcomes; and (4) risk and protective effects of peer relationships. The first three types of analyses included studies that had participants with and without ACEs and treated ACEs as independent variables. The last type of analysis was based on samples (or subsamples), all of whom had the same ACEs, and treated ACEs as a sample inclusion criterion.

Youth outcomes in the mediation and moderation models, as well as the risk and protective effects section, included any outcome variables, such as academic achievement, mental health, and aggression. Within the main effects section, the results are sorted by ACEs, starting with combined ACEs (e.g., cumulative ACE score) and then singular ACEs (e.g., sexual abuse) when relevant. The results are presented in a separate subsection if there are two or more studies on the relation between a specific ACE and peer relations. ACEs with only one study are grouped in one subsection.

Among the mediation models, the paths between the independent variables (i.e., ACEs) and mediators (i.e., peer relations) are also described in the main effect section. Studies on the moderating effect of peer relations rarely reported relations between ACEs and peers. However, when such associations were reported, they were also described in the main effect section. There are two caveats concerning the mediation. First, some studies examined the mediating effect of peer relations in cross-sectional data with no temporal order, which technically are indirect effects (not mediation). Second, some studies reported significant paths between independent variables and mediators, and between mediators and dependent variables, but did not report a formal test of the indirect effect. These studies are described as “possible mediation.”

Peer Relationship Quantity

Associations Between ACEs and Peer Relationship Quantity

Overall, negative relations between ACEs and peer relationship quantity were reported in four of the six studies (see Table 3) utilizing various analysis strategies (i.e., ANOVA, linear regression, regression with propensity score matching), although nonsignificant findings were reported in several of these studies depending on the variable or comparisons (e.g., nominations sent vs. received; Bryan, 2017). The remaining two studies reported either nonsignificant (Wolfe, 2016) or positive associations (Seeds et al., 2010). However, the magnitude of the differences in peer relationship quantity between youth with and without ACEs was small, regardless if it was a negative or positive association (e.g., 0.4–0.5 fewer friends, Bryan, 2017; 1.13 more friends, Negriff et al., 2015). Across all ACEs, parental incarceration was negatively associated with peer relation quantity.

Peer relation quantity was assessed via peer nomination and self-report. An upper limit was set in the peer nomination studies (i.e., up to five male and five female friends). The self-report method included: (1) asking the number of friends (single-item); (2) asking the names of friends and counting the total of the names; or (3) asking if the number of friends was within 0–2 or not. All analyses were cross-sectional. Samples ranged from small convenient (e.g., N = 101; Seeds et al., 2010) to large national samples (e.g., N = 2,575,269; Fontes et al., 2017).

Maltreatment

The associations between maltreatment and peer relation quantity were mixed (i.e., negative, positive, or nonsignificant) across the two studies. Negriff et al. (2015) found that youth in the maltreatment group reported having fewer same-aged friends than the comparison group (4.43 vs. 5.56, p = .01) at Time 2 (10–13 years) but not Time 3 (11–14 years). However, no significant differences were found in the number of older friends at Time 2 and 3 (Negriff et al., 2015). Seeds et al. (2010) reported youth with maternal maltreatment had more close friends (5.00 vs. 3.38, p < 0.05) than counterparts who did not have maternal maltreatment. This association was further demonstrated in a path analysis. This was the only study that reported a positive association between ACE and peer relationship quantity. The authors speculated that adolescents from abusive families might rely more on peers for support (Seeds et al., 2010). Nevertheless, paternal maltreatment was not associated with the number of close friends (Seeds et al., 2010). Of note, the maltreatment in Negriff et al. (2015) did not include sexual abuse, but Seeds et al. (2010) did. The mixed findings across the two studies also suggest relations between maltreatment and peer relation quantity may be subject to several factors’ influence, including youth’s age, same-aged versus older friends, and maternal versus paternal maltreatment.

Parental Incarceration

Negative relations between parental incarceration and peer relation quantity were reported in two studies, both of which analyzed Add Health data. Utilizing propensity score matching and regression, Cochran et al. (2018) reported negative associations of parental incarceration with friendship nominations received and sent in a less conservative matching model. However, such associations became nonsignificant in a more conservative matching model. Thus, differences in friendship nominations may have been an artifact of the matching strategy. Using regression analysis, Bryan (2017) reported that father incarceration was associated with fewer friendship nominations sent but not received (i.e., these adolescents were more likely to withdraw from peers rather than be excluded). However, the magnitude of the difference in friendship nominations sent (i.e., 0.4–0.5 fewer friends) was small in an absolute sense and may not carry substantively meaningful implications for practice.

Other ACEs

One study examined sexual abuse, and one investigated caregiver substance misuse in relation to peer relationship quantity. In a very large cross-sectional Brazilian study (N = 2,575,269) with propensity score matching and regression, Fontes et al. (2017) found that youth who were sexually abused were more likely to report having a limited number of friends (i.e., 0–2 friends) compared to peers who had similar characteristics but were not sexually abused. In a cross-sectional US national sample (N = 4,147), Wolfe (2016) reported no significant difference in the number of self-reported friends (16.80 vs. 16.49, ns) between youth whose mothers had alcohol use disorders and those whose mothers did not.

Quantity as a Mediator

In a cross-sectional study, Seeds et al. (2010) found that maternal maltreatment was positively associated with the number of close friends, which was further negatively related to depression severity. However, the indirect link was nonsignificant.

Summary

ACEs seemed negatively associated with peer relationship quantity. This association may be subject to several factors, including adolescents’ age, age of friends, friendship nominations received versus sent, and from whom the ACEs originated (e.g., maternal vs. paternal). However, the literature was small, and multiple ACEs were not studied in relation to peer relationship quantity. Lastly, it is unclear how substantively meaningful it might be for youth with ACEs to have a small but statistically significant difference in friendship quantity.

Peer Relationship Quality

Associations Between ACEs and Peer Relationship Quality

Across all ACEs (see Table 3), caregiver substance misuse and household mental illness were negatively associated with peer relation quality; maltreatment was not significantly related to quality. The associations between the other ACEs and peer relation quality were negative and nonsignificant, except Lepistö et al. (2012), who reported that combined physical and emotional abuse was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting a mutual friendship. Such results were reached through diverse sample sizes (i.e., ranging from small [e.g., N = 88; Shapiro & Levendosky, 1999] to large [N = 164,580; Bergström et al., 2013]) and various analyses (i.e., chi-square test, t-test, ANOVA, ANCOVA, logistic regression, linear regression, regression with propensity matching, path analysis, and SEM). However, most studies were cross-sectional, and peer relationship quality was primarily measured via self-report, except for three studies that utilized parent-reports (Katz et al., 2007; Morón-Nozaleda et al., 2017; Roetman et al., 2019). The quality of measures ranged from single-item (e.g., Wolfe, 2016) to multi-item measures with sound psychometric properties (e.g., Farruggia et al., 2006).

Maltreatment

Maltreatment was not significantly related to conflicts with friends (Shapiro & Levendosky, 1999; N = 88) or best friend satisfaction (Levendosky et al., 2002; N = 111). Of note, the sample sizes of both studies were relatively small.

Abuse

Mixed (i.e., negative, positive, or nonsignificant) findings were reported on the associations between abuse and peer relation quality across four studies. Combined physical and emotional abuse had a negative association with peer relationship quality (Ban & Oh, 2016) and peer attachment (Ju & Lee, 2018), but was associated with a higher likelihood of youth reporting having mutual friendships (Lepistö et al., 2012). Lepistö et al. (2012) was the only study that reported a positive association between ACE and peer relationship quality (i.e., mutual friendships). Youth who were abused may rely more on friends than their home relationships compared to their counterparts who did not experience abuse at home (Lepistö et al., 2012). Lastly, abuse (no specification of forms) was not related to peer attachment (Lim & Lee, 2017).

Neglect

Negative and nonsignificant findings were reported regarding the relations between neglect and peer relationship quality. Specifically, neglect was negatively related to general peer relationship quality (Ban & Oh, 2016; N = 2070) and peer attachment (Lim & Lee, 2017; N = 2351) but was not associated with peer relation maladjustment (i.e., dysfunctional peer relations; Kwak et al., 2018; N = 1170). Although all three were cross-sectional studies conducted in South Korea, the sample sizes and variables controlled in the analyses differed.

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse was negatively associated with friendship quality in Greger et al., (2016; N = 1352) but not related to conflict with friends in Shapiro and Levendosky (1999; N = 88). The relatively small sample size of Shapiro and Levendosky (1999) should be noted.

Family and Domestic Violence

Negative associations of family and domestic violence with peer relationship quality were reported in two studies, and one study reported nonsignificant findings. In a cross-sectional study across four European countries, Kassis et al. (2018) reported youth who were “resilient” to family violence (i.e., no depression or aggression despite experiencing family violence; n = 510) expressed lower levels of empathy toward peers than the comparison group (i.e., no family violence, no depression or aggression; n = 2055). In a longitudinal study, Narayan et al., (2014; N = 182) reported domestic violence exposure before age 5 was positively related to conflicts with best friends at age 16. In another longitudinal study, Katz et al., (2007, N = 65) reported a nonsignificant association of domestic violence exposure at age 5 with negative peer interactions or friendship closeness at age 11. The relatively small sample size might explain the nonsignificant association. Also, Katz et al. (2007) used mother-reported peer relation quality, whereas Kassis et al. (2018) and Narayan et al. (2014) used youth self-reports. Lastly, the definition of peer relationship quality differed across the three studies.

Caregiver Substance Misuse

Caregiver substance misuse was associated with negative peer relationship quality (i.e., higher peer stress; “not close to friends”) in two studies. Specifically, Marshal et al. (2007) found parental alcoholism was related to higher peer stress. Wolfe (2016) reported maternal alcohol use disorder was positively associated with youth reporting “not close to friends,” although not related to “difficulty to make friends.”

Household Mental Illness

Household mental illness was related to negative peer relationship quality in two studies, with differences between fathers’ and mothers’ mental illnesses. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Spain, Morón-Nozaleda et al. (2017) found youth whose parents had bipolar disorders reported more peer relationship problems than the community control group. In a longitudinal study in Sweden, Roetman et al. (2019) reported maternal mental disorder (including substance disorder) before the child’s 10th birthday was associated with higher odds of peer relation problems at age 15. However, paternal mental disorder was not associated with peer relationship problems.

Divorce and Separation

Mixed (i.e., negative or nonsignificant) findings were reported regarding the associations of parental divorce and separation with peer relations quality across five studies. All studies examined family structure (e.g., stepfamily, single-parent family, two-parent family), which indicated possible divorce and separation. In a UK study (N = 1515), Attar-Schwartz et al. (2009) reported that living in stepfamilies was positively associated with peer relation problems compared to two-parent families and that single-parent families were not associated with peer problems. In a Swedish study (N = 164,580), Bergström et al. (2013) reported that joint child custody and living with one parent were associated with lower peer relationship quality at age 12 compared to two-parent households. However, at age 15, joint child custody was no longer associated with peer quality, although living with one parent was still associated with lower peer relation quality. Findings highlighted additional factors to consider, such as the youth’s age when the divorce or separation occurred.

The three other studies reported nonsignificant associations of family structures with peer relationship quality, intimacy, admiration, as well as conflicts and problems with peers (Flouri & Panourgia, 2011, N = 430, UK; Noack et al., 2001, N = 637, Germany; Tarter et al., 2001, N = 91, US). The sample sizes of these three studies were much smaller than the two prior studies. Studies examining divorce and separation might require a larger sample size, as the total sample is often divided into more than two groups to reflect multiple family structures and the non-nuclear family structure groups usually represent a small percentage of the total sample. Also, the effect of family structure on peer relation quality might be small, although statistically significant. Lastly, these five studies were from five different countries.

Child Welfare Involvement

Negative associations between child welfare involvement and peer relation quality were reported in two studies, and one study reported nonsignificant results. Youth in foster care had lower friendship quality than youth in the general population, as rated by themselves and their primary caregivers (Jozefiak & Sønnichsen Kayed, 2015). Youth in foster care were also less likely to report “friends care a lot” (Perry, 2006) than youth in the general population, but did not differ from their counterparts in terms of perceived peer warmth (Farruggia et al., 2006). The definitions of peer relation quality differed slightly across the three studies, yet they all compared peer relation quality of youth in foster care with their counterparts.

Other ACEs

One study examined the associations of the following ACEs with peer relationship quality: the cumulative ACE score, household dysfunction, physical abuse, and parental incarceration. The cumulative ACE score was negatively associated with peer relation quality in a short-term longitudinal study (Landers et al., 2020). A nonsignificant association between household dysfunction (i.e., parental psychopathology, criminality, and alcohol or substance abuse) and peer relation quality was reported in a cross-sectional study (Greger et al., 2016; N = 1352). Physical abuse was not associated with friendship quality (Greger et al., 2016). Lastly, Cochran et al. (2018) reported in a nationally representative sample that parental incarceration was not associated with youth reporting having a best friend.

Quality as a Mediator

Mixed (i.e., significant or nonsignificant) findings were reported regarding the mediating role of peer relation quality across seven studies. When a mediating effect was found, youth with ACEs tended to have lower peer relation quality which in turn had negative implications for their well-being. A strength of the literature was that most studies provided a formal significance test of the mediation, except Kwak et al., 2018 (this was irrelevant due to the nonsignificant path between the independent variable and mediator). However, most studies included fewer than three waves of data except for Ju and Lee (2018) and Narayan et al. (2014). The studies included five ACEs as independent variables, six variations of peer relation quality as mediators, and nine youth outcomes as independent variables.

Specifically, Landers et al. (2020) reported that positive peer relationships mediated the association of the cumulative ACE score with youth behavioral needs (e.g., conduct problems, oppositional behavior, and anxiety) and life functioning (e.g., social functioning, employment, and living situation). Ban and Oh (2016) found general peer relation quality mediated the associations of abuse and neglect with emotional and behavioral problems. Further, peer attachment mediated the relations of abuse with depression (Ju & Lee, 2018), as well as the relations of neglect with school adjustment (Lim & Lee, 2017). Lastly, peer stress mediated the relations between parental alcoholism and youth alcohol involvement in participants with ADHD but not in participants without ADHD (Marshal et al., 2007). Of note, the interaction between parental alcoholism and ADHD (in relation to peer stress) was “significant” at 0.15 in Marshal et al. (2007), indicating it was not advisable to proceed with mediation analysis within the two subsamples (ADHD vs. comparison).

Nonsignificant findings were also reported. Specifically, positive peer relationships did not mediate the association of the cumulative ACE score with youth risk behavior (Landers et al., 2020). Peer attachment did not mediate the relation between abuse and school adjustment (Lim & Lee, 2017). Further, peer relation maladjustment did not mediate the relation between neglect and smartphone addiction (Kwak et al., 2018). Lastly, conflicts with best friends at age 16 did not mediate the relations between domestic violence exposure before age 5 and young adult dating violence (Narayan et al., 2014).

Quality as a Moderator

Both significant and nonsignificant moderating effects of peer relation quality were reported across the five studies. Specifically, problem behaviors with best friends amplified the association of physical abuse with youth delinquency (Salzinger et al., 2007). Positive peer relationships mitigated the negative relation between maternal alcohol use disorder and youth mental health (Wolfe, 2016). However, the time youth spent with friends did not moderate the relation between the cumulative maltreatment score and youth offending behavior (Wilkinson et al., 2019). Peer attachment did not moderate the relation between physical abuse and youth delinquency (Salzinger et al., 2007). Peer closeness did not moderate the association between family violence and later youth anxiety (Goodearl et al., 2014). Lastly, peer connectedness did not moderate the relation between physical abuse and nonproblematic behavior (Merritt & Snyder, 2015).

Risk and Protective Effects of Quality

Overall, the seven studies indicated that high quality peer relationships were a protective factor for youth with ACEs, whereas low quality was a risk factor, with caveats to consider (e.g., internalizing vs. externalizing problems; S. Yoon et al., 2021). Such results were reached through various analyses (i.e., t-test, linear and logistic regression, path analysis, and latent growth models) and diverse sample sizes (i.e., ranging from 73 [Jaser et al., 2007] to 1,054 [Merritt & Snyder, 2015]). However, most of the studies were cross-sectional except for S. Yoon et al. (2021).

Six of the seven studies examined child welfare involvement as an ACE, three of which utilized NSCAW-II or NSCAW data. Utilizing longitudinal NSCAW-II data, S. Yoon et al. (2021) reported in a sample of youth investigated by child protective services that peer relation satisfaction was associated with low initial levels of and a slower rate of decline in internalizing and posttraumatic stress symptoms across three waves. However, peer relation satisfaction was not related to externalizing behaviors. Utilizing the same dataset (NSCAW-II), Merritt and Snyder (2015) reported that perceived school peer connectedness was associated with increased odds of nonproblematic behavior (i.e., T score lower than 60 on the Child Behavior Checklist) among youth in child welfare. Lastly, H. M. Thompson et al. (2016) reported in NSCAW data that low peer relation quality was related to more externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors, and delinquency, as well as a lack of self-esteem among youth in foster care.

In addition, Farruggia et al. (2006) reported among youth in foster care that peer warmth was positively related to concurrent youth mental health but not achievement or misconduct. J. W. Kim et al. (2015) conducted a cross-sectional t-test in a South Korean child welfare-involved sample and found youth with low quality peer relations reported lower cognitive functioning and more internet addiction, ADHD, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Perry (2006) reported among youth in foster care that peer network strength was positively related to foster network strength, but was not associated with youth depression, anxiety, or biological network strength.

Lastly, in a cross-sectional sample of 73 adolescents, all of whom had a parent with depression, Jaser et al. (2007) found that primary control coping (e.g., problem-solving) of peer stress was negatively associated with self-reported anxiety, depression, and aggression, but not parent-reported aggression. Secondary control coping (e.g., distraction) was negatively associated with anxiety and depression, but not aggression (neither self- nor parent-report). Disengagement coping (e.g., avoidance) was not related to anxiety, depression, or aggression.

Summary

Peer relation quality plays a critical role in the well-being of youth with ACEs, as evidenced in the mediating, moderating, and risk and protective effects. However, not all ACEs were included in the examination of these effects. In particular, the risk and protective effects were investigated in samples mostly consisting of youth in child welfare. The associations between ACEs and peer relation quality were studied in more ACEs, three of which showed consistent patterns: Caregiver substance misuse and household mental illness were negatively related to peer relation quality, whereas maltreatment was not significantly associated with quality. The associations between the other ACEs and peer relation quality were mostly a mix of negative and nonsignificant findings. Such associations may be subjected to multiple factors, including participant age when the ACEs occurred (Bergström et al., 2013), which caregiver the ACEs were from (e.g., maternal vs. paternal; Roetman et al., 2019), and how peer relation quality was defined (e.g., general quality, intimacy, and conflicts with friends). Lastly, the presence of protective factors (e.g., closeness) was rarely considered alongside the absence of risk factors (e.g., conflicts with friends) of peer relation quality in relation to ACEs.

Peer Characteristics

Associations Between ACEs and Peer Characteristics

Across all ACEs examined (see Table 3), emotional abuse, caregiver substance misuse, and parental incarceration were associated with negative peer characteristics. Composite ACEs were not significantly related to peer characteristics. The relations of the other ACEs with peer characteristics were a mix of negative or nonsignificant findings, except that Negriff and Trickett (2012) found maltreatment was related to positive peer characteristics (i.e., lower levels of peer alcohol use). Such results were reached through a range of analytic strategies (i.e., chi-square test, t-test, ANOVA, logistic regression, Poisson regression, linear regression, regression with propensity score matching, and path analysis) and diverse samples (i.e., ranging from small cross-sectional samples [e.g., N = 91; Tarter et al., 2001] to large longitudinal national samples [e.g., N = 811; 3 waves across 4 years, LONGSCAN; Yoon et al., 2020]). Peer characteristics were primarily assessed through youth self-report, except for a few studies that utilized parent-report (Fergusson & Horwood, 1999; J. E. Kim et al., 1999) or peer-report measures (Bryan, 2017; Cochran et al., 2018). Measure quality ranged from single-item measures with no psychometric information (e.g., Negriff & Trickett, 2012) to multi-item measures with sound psychometric properties (e.g., Yoon et al., 2020).

Composite ACEs

Nonsignificant associations between composite ACEs and peer characteristics were reported across two studies. Analyzing LONGSCAN data with path analysis, Morrow and Villodas (2018) reported the cumulative ACE score (0–14 years) was not associated with prosocial peer affiliation at age 16. Also using path analysis, Mason et al. (2017) reported ACE in preschool (i.e., an average of neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and domestic violence) was not directly related to peer cannabis use and approval in adolescence, although the two constructs might be indirectly linked via parent attachment.

Physical Abuse

Three studies reported nonsignificant associations between physical abuse and peer characteristics, and one study indicated physical abuse was related to negative peer characteristics. Specifically, physical abuse was not related to peer violence in cross-sectional (Faus et al., 2019) or longitudinal (Walters, 2020) studies. Physical abuse (0–12 years) was also not associated with deviant peer affiliation at age 14 in a longitudinal study using LONGSCAN data (Yoon et al., 2020). However, Logan et al. (2009) reported in a cross-sectional survey that physical abuse (0–10 years) was associated with higher peer criminal activity involvement in Grade 7 (12 years). A single item was used to measure peer criminal activity by Logan et al. (2009); thus, caution should be exercised in interpreting the finding.

Sexual Abuse

Associations between sexual abuse and negative peer characteristics were reported in two of the four studies. Fergusson and Horwood (1999) reported a positive relation between sexual abuse and deviant peer affiliation in a longitudinal study, and Faus et al. (2019) found a positive association between sexual abuse and friend violence in a cross-sectional study. However, Yoon et al. (2020) reported in LONGSCAN data that sexual abuse was not associated with later deviant peer affiliation. Lastly, Mason et al. (2017) reported in a longitudinal study that sexual abuse was not directly associated with peer cannabis use and approval, although these two variables might be indirectly linked via parent attachment.

Emotional Abuse

The two studies reviewed indicated emotional abuse was related to negative peer characteristics (i.e., friend violence, deviant peer affiliation). Faus et al. (2019) reported emotional abuse was positively associated with concurrent friend violence. Yoon et al. (2020) found emotional abuse (0–12 years) was positively related to later deviant peer affiliation at age 14.

Caregiver Substance Misuse

The four studies reviewed suggested associations of caregiver substance misuse with negative peer characteristics (i.e., peer substance use, deviant peer affiliation). Positive relations between parental substance misuse and affiliation with substance-promoting peers were reported in two longitudinal studies (Feske et al., 2008; Haller et al., 2010). In another longitudinal study, Fergusson and Horwood (1999) reported that parental history of alcoholism and illicit drug use was positively associated with deviant peer affiliations. Lastly, Barnow et al. (2002) reported that family alcoholism history and concurrent peer substance use might be indirectly linked via parental psychiatric diagnosis and youth aggression and delinquency, although the direct link was nonsignificant.

Parental Divorce and Separation

Four studies reported divorce and separation were related to negative peer characteristics, whereas the other three studies suggested nonsignificant findings. Most studies (n = 5) used cross-sectional designs and mean comparisons (e.g., t-test, ANOVA). However, these studies examined a range of peer characteristics, including peer substance use, delinquency, violence, and deviant or constructive peer affiliations. Regarding peer substance use, youth who did not live with two biological parents (i.e., single-parent, stepparent, non-parent) were more likely to report having friends attempting or using substances (Hollist & McBroom, 2006), and the association between divorce and peer substance use was possibly mediated by parental contact (Novak et al., 2007). However, Tarter et al., (2001; N = 91) reported no significant differences in peer drug use between boys whose substance-abusing fathers lived in the home and those who were divorced or separated from their mothers. This finding should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size and given that divorce and separation were studied with substance-abusing fathers (Tarter et al., 2001).

Regarding peer delinquency, J. E. Kim et al., (1999; N = 654) found that youth from stepfather families reported more peer delinquency than youth in non-stepfamilies, but Tarter et al., (2001; N = 91) reported nonsignificant findings. In terms of peer affiliation, Fergusson and Horwood (1999) found in New Zealand that youth entering a single-parent family at birth or having two or more changes of parents were more likely to report deviant peer affiliation. However, Noack et al., (2001; N = 637), in their analyses of both constructive and deviant peer affiliations, reported no significant differences across family structures in German youth. Lastly, parental divorce and separation were not associated with later peer violence (Walters, 2020).

Parental Incarceration

Two studies utilized the same dataset (i.e., Add Health) and indicated that parental incarceration was related to some negative peer characteristics (e.g., lower friend GPA) but not others (e.g., having drunk friends). Using regression analysis, Bryan (2017) reported that father incarceration was associated with having a greater proportion of friends with incarcerated parents, higher rates of friend delinquency, fewer friends from two-parent families, and lower friend GPA. Using regression with propensity score matching, Cochran et al. (2018) reported in a conservative matching model that parental incarceration was related to having friends with higher rates of lying and fighting as well as lower GPAs, but not associated with friends’ smoking, drinking, getting drunk, or skipping school. In a less conservative model, friends’ smoking and skipping school were positively associated with parental incarceration.

Other ACEs

One study examined the associations of the following ACEs with peer characteristics: maltreatment, neglect, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and child welfare involvement. Negriff and Trickett (2012) found the maltreatment group reported less peer alcohol use at Time 3 (mean age = 13.74 years) than the comparison group but not peer cannabis use, whereas at Time 2 (mean age = 12.11 years), neither peer alcohol nor cannabis use differed across the two groups. Such findings suggest the associations between maltreatment and peer characteristics are possibly subjected to the influence of youth’s age and the type of peer characteristics. Of note, this was the only study that showed ACE was related to a positive peer characteristic (i.e., less peer alcohol use).

In addition, Yoon et al. (2020) found that neglect (Grade 1 to age 12), a latent variable including physical, emotional, and educational neglect as well as inadequate supervision, was not associated with later deviant peer affiliation at age 14. Further, Faus et al. (2019) reported emotional neglect was not associated with concurrent friend violence, but physical neglect was related to higher levels of friend violence. Lastly, Kepper et al. (2014) found youth in residential care reported more peer deviance than youth in special education.

Peer Characteristics as a Mediator

Across the six studies, the mediating effect of peer characteristics was reported in two studies and suggested in three studies. When there was a mediating effect, youth with ACEs were more likely to be affiliated with peers who had negative characteristics, which in turn had negative implications for their well-being. A strength is that most (n = 5) studies included three waves of data or more. A limitation is that half of the studies did not report a formal significance test of the mediation, although they reported significant direct paths between independent variables and mediators, as well as mediators and dependent variables. These studies are described as “possibly mediated” below. The six studies included seven ACEs as independent variables, two mediators (peer substance use and peer affiliation), and two dependent variables (youth substance use, n = 5; school dropout, n = 1). For school dropouts, Morrow and Villodas (2018) reported prosocial and deviant peer affiliations at age 16 did not mediate the relation of the cumulative ACE score (0–14 years) with high school dropout.

Regarding youth substance use, peer substance use possibly mediated the links of a range of ACEs (i.e., parental substance misuse, sexual abuse, composite ACEs, divorce) with the youth’s own substance use. Feske et al. (2008) reported in a male sample that peer substance use at age 16 mediated the relation of maternal substance use disorder with youth’s cannabis use disorder and frequency at age 22. No significance test was reported for the same mediation model regarding paternal substance use disorder. Haller et al. (2010) suggested that substance-promoting peers possibly mediated the relation of parental alcoholism with youth drug and alcohol use. Mason et al. (2017) indicated that peer cannabis use and approval possibly mediated the relation of sexual abuse and composite ACE (average score of physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and domestic violence) with youth cannabis use. Novak et al. (2007) indicated that peer narcotic use possibly mediated the relation of parental divorce with youth smoking. Lastly, deviant peer affiliation at age 14 mediated the relation of emotional abuse (0–12 years) with youth substance use (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis) at age 16, but did not mediate the association of sexual abuse, physical abuse, or neglect with youth substance use (Yoon et al., 2020).

Peer Characteristics as a Moderator

Five of the six studies reported moderating effects of peer characteristics on the relations between ACEs and youth outcomes, with some nuances to consider, such as who perpetrated the ACE (e.g., mother- vs. father-perpetrated domestic violence; Gage, 2016) and the moderated youth outcome (e.g., dating violence perpetration vs. victimization; Garrido & Taussig, 2013). Typically, positive peer characteristics (e.g., prosocial peers) mitigated the negative effect of ACEs on youth well-being, whereas negative peer characteristics (e.g., peer deviance) exacerbated the implications of ACEs.

Three studies examined the associations of family or domestic violence (DV) with youth outcomes moderated by peer characteristics. Garrido and Taussig (2013) found that prosocial peer relations mitigated the association of DV exposure with youth dating violence perpetration but not victimization. Gage (2016) reported among boys that peer acceptance of dating violence exacerbated the relation of mother-perpetrated DV with youth dating violence perpetration but mitigated the association of father-perpetrated DV with youth dating violence perpetration; no moderating effects were found in girls. Goodearl et al. (2014) reported friend’s antisocial behavior did not moderate the relation of family violence with youth aggression. Of note, Goodearl et al. (2014) was longitudinal; Garrido and Taussig (2013) and Gage (2016) were cross-sectional.

The other three studies investigated physical abuse, divorce, and parental substance use, and all showed some moderating effect of peer characteristics. In a longitudinal study, Salzinger et al. (2007) found that low friend delinquency mitigated the relation between physical abuse and youth delinquency. In a cross-sectional study, Kendler et al. (2014) reported that peer deviance exacerbated the association between parental divorce and youth drug abuse. Lastly, Henry et al. (2018) reported in a longitudinal study that friend substance use exacerbated the relation of father substance use with youth substance use, but not mother substance use with youth substance use. The authors attributed this difference to the smaller mother–child dyad sample (N = 167) compared to the father-child dyad sample (N = 246) and the low maternal substance use rate.

Risk and Protective Effects of Peer Characteristics

Overall, the eight studies suggested negative peer characteristics were associated with maladaptive outcomes in youth with ACEs, whereas positive peer characteristics were related to adaptive youth outcomes, with nuances to consider (e.g., friend use of cannabis vs. alcohol; R. G, Jr. Thompson & Auslander, 2007). Such results were reached through various analyses (i.e., t-test, linear and logistic regression, and path analysis) and diverse sample sizes (i.e., ranging from 163 [Farruggia et al., 2006] to 3,281 [Perkins & Jones, 2004]). However, most studies were cross-sectional, except for Cheng and Li (2017), and all studies used self-reported peer characteristics. Measure quality ranged from single-item (e.g., R. G, Jr. Thompson & Auslander, 2007) to multi-item measures with good psychometrics (e.g., Farruggia et al., 2006). Additionally, most studies examined negative peer characteristics, with few investigating positive ones. In terms of ACEs, six studies examined child welfare, one examined physical abuse, and one investigated caregiver substance misuse.

Of the six studies examining child welfare, three analyzed NSCAW or NSCAW-II data. Leslie et al. (2010) analyzed NSCAW data and found that affiliating with deviant peers was associated with more health-risk behaviors in youth undergoing investigation for neglect and abuse. Using NSCAW-II data, Cheng and Li (2017) found deviant peer affiliations were related to more delinquent behaviors in youth involved with child welfare. Also using NSCAW-II data, Merritt and Snyder (2015) found that fewer deviant peer affiliations were related to increased odds of nonproblematic behavior in youth involved with child welfare.

Farruggia et al. (2006) and Farruggia and Sorkin (2009) reported similar patterns for the associations between peer characteristics and youth outcomes in a foster care sample from Los Angeles. Farruggia et al. (2006) reported peer problem behavior was positively associated with youth misconduct but not achievement or mental health. Using the same dataset, Farruggia and Sorkin (2009) found a positive association between peer health-compromising behaviors (e.g., drug use) and youth health-compromising behaviors that were, in turn, associated with their general health. In the last foster care sample, Thompson and Auslander (2007) reported peer cannabis and other substance use were related to higher odds of youth alcohol and cannabis use. However, peer alcohol use was not related to the odds of youth alcohol and cannabis use.

The remaining two studies examined physical abuse and caregiver substance misuse as ACEs. In a large sample of youth who were physically abused, Perkins and Jones (2004) found positive peer characteristics (i.e., high positive peer behavior such as helping people; low negative peer behavior such as drug use) were related to lower odds of youth risk behaviors (i.e., alcohol, tobacco, and drug use; sexual activity; antisocial behavior; suicide; purging) and increased odds of youth thriving behaviors (i.e., school success; helping others). Dawes et al. (1999) analyzed a male sample whose fathers had substance abuse disorders (N = 375); their novel measurement of peer delinquency (i.e., the proportion of peers who were delinquent) was not associated with youth’s behavioral self-regulation.

Summary

Peer characteristics have substantial implications for the well-being of youth with ACEs, as shown in the literature on its mediating, moderating, and risk and protective effects. Of note, the literature on the mediating and moderating effects included more ACEs, whereas the risk and protective effects were mostly examined in samples of youth in child welfare. Regarding the association between ACEs and peer characteristics, four ACEs showed consistent patterns: emotional abuse, caregiver substance misuse, and parental incarceration were associated with negative peer characteristics, and composite ACEs were not significantly related to peer characteristics. The relations of other ACEs with peer characteristics were largely comprised of negative and nonsignificant findings, or not studied at all. Lastly, the literature predominantly focuses on negative peer characteristics versus positive peer characteristics (e.g., prosocial peer affiliations; Morrow & Villodas, 2018).

Peer Support

Associations Between ACEs and Peer Support

Nonsignificant relations between ACEs and peer support were found in five studies, and the remaining two studies reported significant associations using foster care samples (Browne, 2002; Long et al., 2017). Such results were reached in a variety of samples, ranging from small convenience (N = 21; Browne, 2002) to large national samples (N = 28,828; Long et al., 2017). However, most analyses were mean comparisons (i.e., t-test, chi-square, Mann–Whitney test, and ANOVA), except for one study that used logistic regression (Long et al., 2017). All studies were cross-sectional and assessed peer support via youth self-report, with measures ranging from single-item measures with no psychometric information (e.g., Long et al., 2017) to multiple-item measures with strong psychometrics (e.g., Pinchover & Attar-Schwartz, 2018).

Child Welfare Involvement

The association between child welfare involvement and peer support was mixed (i.e., positive, negative, or nonsignificant) in the two studies. In a large UK national sample (N = 28,828; foster care group, n = 295), Long et al. (2017) reported youth in foster care were more likely to report either a low or high ability to rely on their friends (medium ability was the reference group), compared to peers living with parents. In other words, youth in foster care seemed more likely to take up the extremes (either low or high) of the ability to rely on friends for support. In a US sample (N = 326; foster care group, n = 163), Farruggia et al. (2006) reported no significant differences in peer support between foster care and comparison groups.

Other ACEs

One study examined the relations of the following five ACEs with peer support: maltreatment, abuse (physical or sexual), sexual abuse, household mental illness, and parental divorce and separation. Nonsignificant findings were reported in four of five studies. Negriff et al. (2015) reported no significant differences between maltreated and comparison groups in terms of perceived social support from same-aged or older friends. In a small sample of youth living in foster care (N = 21), Browne (2002) found that youth with a history of physical or sexual abuse were less likely to turn to friends for support compared to youth without such abuse history. In another small sample (N = 54) of sexually abused sex offenders, non-abused sex offenders, and a comparison group (i.e., no history of sexual abuse or offenses except for property offenses), no significant differences were found across groups in terms of youth’s perceived peer support (Symboluk et al., 2001). Selimbasic et al. (2009) asked youth to choose the most important support people (e.g., mother, schoolmate). They found no significant differences between youth whose parents had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and youth whose parents did not have PTSD in terms of the relative importance of peers as support people. Lastly, in an Israeli educational residential care sample, Pinchover and Attar-Schwartz (2018) reported no significant differences in perceived peer support between youth whose parents were married or cohabitating and youth whose parents were divorced or separated.

Peer Support as a Moderator

Two studies examined peer support as a moderator on the associations of ACEs with several youth outcomes. In a cross-sectional study (N = 111), Levendosky et al. (2002) reported significant interactions between maltreatment and friend support on best friend satisfaction and dating partner satisfaction, but not dating violence perpetration or victimization, or negative communication with a dating partner. They also reported significant interactions between domestic violence and friend support on best friend satisfaction, dating violence perpetration and victimization, as well as negative communication with a dating partner, but not dating partner satisfaction (Levendosky et al., 2002). However, no simple slope tests were reported for these interactions. Thus, it was unclear if relations between ACEs and youth outcomes were stronger or weaker among youth with more friend support.

In another cross-sectional study (N = 2011), Rodgers and Rose (2002) reported several significant 3-way interactions among family structure (i.e., one ACE; included intact, blended, divorced, and single-parent), parent support and monitoring, and peer support on youth internalizing and externalizing problems. Simple slope tests suggested that peer support mitigated the effect of parent monitoring on internalizing problems among youth from intact families but not blended or divorced single-parent families. Peer support also mitigated the effect of low parent support on internalizing problems in youth from divorced single-parent families but not intact or blended families. Peer support did not mitigate against the effect of low parent support on externalizing problems across family types.

Risk and Protective Effects of Peer Support

Overall, the relations between peer support and youth outcomes were mixed across the five studies, with two reporting peer support was related to adaptive youth outcomes and three suggesting nonsignificant relations. Analytical strategies included logistic and linear regression. Most of the studies were cross-sectional, except for Khambati et al. (2018). Sample sizes ranged from 112 (Lipschitz-Elhawi & Itzhaky, 2005) to 5,551 (Cheung et al., 2017). Peer support was assessed via self-report across all studies, with measures’ quality ranging from single-item (e.g., Hébert et al., 2014) to multi-item measures with good psychometric properties (e.g., Farruggia et al., 2006). The studies examined multiple ACEs: a composite ACE score, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and foster care.

Specifically, in a large sample of youth with ACE (i.e., a composite score of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, physical neglect, and interparental violence exposure), Cheung et al. (2017) found that disclosing one’s worries to friends was associated with positive youth mental health. However, the frequency of youth disclosing concerns to friends or being able to rely on friends when encountering serious problems was not related to mental health. It should be noted that single-item measures for peer support were analyzed in Cheung et al. (2017). In a Canadian sample who had sexual abuse (N = 694; 82.6% female), Hébert et al. (2014) found that an increase in peer support was associated with decreased odds of youth reaching the clinical level of PTSD symptoms.

In contrast, the three other studies found nonsignificant relations between peer support and youth outcomes. Khambati et al. (2018) followed a longitudinal UK sample who had emotional (N = 1,118) or physical (N = 375) abuse in early childhood (0–5 years) and found that supportive friendships in adolescence were not associated with educational outcomes, mental well-being, or self-esteem. Lipschitz-Elhawi and Itzhaky (2005) studied an Israeli sample (N = 112; 84.8% male) of youth in residential treatment centers due to home maltreatment. Peer support was not associated with academic, social, or personal adjustment. Lastly, in a US sample of youth in foster care (N = 163), Farruggia et al. (2006) found that peer support was not related to youth mental health, achievement, or misconduct.

Disclosure Confidant as a Unique form of Peer Support

Although the effects of peer support on youth outcomes were mixed, as mentioned above, youth often turned to friends as a first line of support (i.e., disclosed ACEs to friends). Specifically, friends were an important disclosure confidant for sexual abuse and other ACEs across all six studies, with some caveats to consider, such as gender differences (Edinburgh et al., 2006) and source of ACEs (Stein & Nofziger, 2008). Of note, some youth disclosed the ACE to only one confidant, whereas others told multiple people. All studies conducted frequency counts in cross-sectional samples.

In a population-based Finnish sample (N = 11,419; 73% female; n = 256 with sexual abuse), Lahtinen et al. (2018) found friends were the most frequent disclosure confidant for those who were sexually abused for the first time. Lam (2014) reported in a Hong Kong sample (N = 830; 72% female; n = 177 with sexual abuse) that most youth who disclosed sexual abuse chose to tell friends. Edinburgh et al. (2006) studied the disclosure pattern of extrafamilial sexual abuse in a US sample (N = 290; 78% female) and found girls were most likely to disclose to peers, whereas boys were most likely to disclose to other adults, with peers being the third likely disclosure confidant. Stein and Nofziger (2008) reported in a US national sample (N = 4,023; n = 326 with sexual victimization) that friends were the most frequent confidant across all sexual victimization disclosures. However, when considering relationships with the perpetrators, friends remained the most frequent confidant for sexual victimization caused by a friend, but mothers were the most frequent confidant for sexual victimization caused by a family member (Stein & Nofziger, 2008). Additionally, disclosure to mothers was related to increased odds of arrest, whereas disclosure to friends was not related to perpetrator arrest (Stein & Nofziger, 2008).

In an Indian female sample (N = 1,060), Daral et al. (2017) reported that friends were the most frequent disclosure confidant for physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect, but not sexual abuse. Lastly, in a Canadian sample (N = 1,099; 71% female), Ungar et al. (2009) reported friends were the second most frequent disclosure confidant for total maltreatment, physical abuse, and neglect, and the third disclosure confidant for sexual and emotional abuses.

Summary

The literature on peer support is small compared to other peer relation aspects (i.e., peer quality, peer characteristics). The perception of peer support in youth with ACEs was comparable to peers without ACEs in most (i.e., five of seven) studies. Further, peer support had significant implications for the well-being of youth with ACEs, based on the moderating and “protective” effects of peer support on several outcomes and youth often turned to friends as the first line of support (i.e., disclosure confidant). However, peer support was not always related to positive youth outcomes, and there were no studies that examined its mediating effects.