Abstract

There is growing evidence that adolescents in high socioeconomic status groups may be at increased risk for some mental health concerns. This scoping review aims to synthesize empirical literature from 2010 to 2021 on mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors among this adolescent group. Six comprehensive electronic databases yielded 1316 studies that were systematically reviewed in Covidence to identify relevant research. PRISMA-ScR analysis was used. Eighty-three studies met the eligibility requirements. NVivo was employed for coding, data extraction, and analysis. Key findings suggest substance use, in particular, alcohol, is the main mental health concern among adolescents in high socioeconomic status groups. Other main mental health concerns were externalizing and risk behaviors, bullying, depression, anxiety and stress. These concerns were shown to be influenced by parents, peers, school, and neighborhood contextual factors. Three emerging subgroups were identified as being at higher risk of mental health concerns among adolescents in high socioeconomic status groups. Specifically, adolescents residing in boarding schools, those with high subjective social status (e.g., popular) or low academic performance. Being pressured by parents to perform well academically was identified as a risk-factor for substance use, depression and anxiety. Albeit limited, areas explored for help-seeking behaviors centered on formal, semi-formal and informal support. Further research examining multi-level socioeconomic status factors and mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors are urgently needed to inform appropriate interventions for this under-represented group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents in high socioeconomic status (SES) groups are emerging as an important subgroup at risk of mental health concerns, yet there has been limited research exploring how they seek help and support (Coley et al., 2018; Luthar et al., 2018). High SES groups encompass individuals at the highest level of a socioeconomic scale, as determined by factors such as place of residence, education, and occupation (American Psychological Association, 2015). While research examining mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups are in their infancy, identifying the nature of these concerns and uncovering key barriers to help-seeking behaviors is an important first step towards informing future prevention and early intervention efforts (Divin et al., 2018). Failure to recognize these concerns and contributing contextual factors can lead to under-diagnosis and under-treatment, resulting in a broad range of adverse outcomes (e.g., suicide; DeHann, 2016; Islam et al., 2022). As such, this study aims to conduct a scoping review to synthesize the current empirical literature on the mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors of adolescents in high SES groups.

Despite the traditional perception of adolescents in high SES groups as having access to significant protective factors for mental health, national and cross-national studies have demonstrated similarities between adolescents at the extreme ends of the socioeconomic spectrum (AIHW, 2022; Luthar & Kumar, 2020). For example, greater externalizing problems, as well as higher rates of major depressive disorder, have been reported among adolescents in families of either low or high SES (Lund et al., 2017; Zubrick et al., 2017). Similarly, adolescents in high SES groups can experience higher levels of mental health concerns related to substance misuse (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes, and cannabis) than peers in other SES groups (Racz et al., 2011). A significant interaction between school failure and SES on illicit drug use has also been reported in a Swedish longitudinal study, with an increased effect of school failure with increasing SES (Gauffin et al., 2013).

Adolescents in high SES groups face barriers to help-seeking for mental health concerns (Bogard, 2005). However, the majority of research to date has focused on help-seeking among high SES adults (Weitzman, 2000). For example, women in high SES groups with lived experience of domestic violence were reluctant to seek help, valuing secrecy over disclosure, with concerns around perceived community culture, familial status, partners’ economic and political roles, and social expectations (Haselschwerdt & Hardesty, 2017). While adolescents in high SES groups are likely to have greater means to access to health services and support, young people from low and medium SES groups have been found to engage with more health and school services than their high SES peers (Cummings, 2014; Vu et al., 2018). These differences might be attributable to a “culture of affluence” (Luthar et al., 2003), where the unique social environment of adolescents in high SES groups might hinder help-seeking due to power, privilege, and stigma or shame about seeking help for mental illness (Bernard, 2018; Pfaffendorf, 2019).

Any exploration of adolescent mental health concerns or help-seeking during this developmental period needs to be undertaken within a framework that considers contextual influences on behavior for the most accurate and nuanced understanding of these experiences (Ashiabi & O’Neal, 2015; Troy et al., 2023). Bronfenbrenner’s (1992) bioecological theory of human development for mental health concerns and the help-seeking measurement framework (Rickwood et al., 2012) for help-seeking behaviors are two such models that encourage consideration of how individual or contextual factors might influence these concerns and behaviors specific to adolescents in high SES groups, and has been utilized in previous studies (Spencer et al., 2018). Within the microsystem that surrounds them, adolescents experience a multitude of external (e.g., school, parents, peers) and internal pressures (e.g., expectations of academic achievement; Levine, 2006; Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017). These stressors (and other contextual factors within the microsystem) may modulate the relationships between high SES and mental health, yet remain critically underexplored in the literature (Maenhout, 2020). Bronfenbrenner’s model and the help-seeking measurement framework are therefore appropriate and pertinent frameworks for synthesizing and interpreting research in this emerging area (Bronfenbrenner, 1992; Rickwood et al., 2012).

Current Study

A synthesis of the evidence base is critically needed to consolidate current knowledge about mental health concerns in adolescents in high SES groups, and the particular challenges they face within their environment. Specifically, this scoping review sought to address an important research question related to what is currently known about the mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors among adolescents in high SES groups and which contributing contextual factors (e.g., parents, peers, schools, neighborhood) have been identified. Findings were organized and discussed adopting the microsystem of the Bronfenbrenner ecological systems framework and the help-seeking measurement framework.

Methods

This study was conducted and reported following the PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., 2018). Steps included protocol and registration, eligibility criteria, study selection, information sources, search strategy, data-charting process, data items, and synthesis of results. A critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence was discretionary under the PRISMA-ScR guidelines and was not conducted (Tricco et al., 2018).

Eligibility Criteria

To be included in the review, studies needed to focus on mental health concerns (e.g., alcohol and other drugs, anxiety, depression, or stress) or adolescent help-seeking behaviors (e.g., perceptions or barriers to treatment) in high socioeconomic-level groups, specifically or as part of a broader comparison of low, medium, and high SES groups. The review included peer-reviewed journal studies published in English between 2010 and 2021, examining adolescents ranging from ages 10 to 19 years, following the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022; longitudinal studies including younger or older ages were accepted). Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies were included. Studies were excluded if they focused on country inequality, physical health, actual academic performance (as opposed to pressure and impact of mental health), specific learning disorders, or general mental health related to sleep, self-esteem, and well-being. Grey literature sources, including dissertations and theses were excluded.

Information Sources

Potential databases were identified related to psychology, social sciences, and health related disciplines; scanned for suitability and shortlisted. A comprehensive and specific search strategy was developed through identifying and testing keywords and combinations from preliminary readings in shortlisted databases specific to adolescents in high SES groups or families of affluence. To identify potentially relevant studies, six comprehensive electronic databases (APA PsychInfo via OVID, Cinahl Plus, EMBASE via OVID, ProQuest, PubMed, and Wiley) were selected for sourcing scholarly literature.

Search

Table 1 presents an example of an electronic search strategy. Supplement 1 contains the final full search strategy.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

The research team conducted database searches on March 3, 2021. The lead reviewer JM, with psychology qualifications, undertook the literature search and exported the identified studies to Covidence to select sources of evidence. Another reviewer, also with psychology qualifications JMc, joined the selection process and they worked simultaneously to screen titles in Covidence to determine eligibility for inclusion in the review. The two reviewers verbally discussed and immediately resolved discrepancies regarding the eligibility of individual studies. The inter-rater reliability between reviewers was 0.88, kappa 0.75.

Data-charting Process and Data Items

Nvivo was employed for coding, data item extraction, and synthesizing of the results. The lead reviewer developed a data-charting form in NVivo to determine which variables to manually extract. Main data items extracted included authors, years of publication, country or countries, study population and SES (i.e., high, medium, and low), and SES variables and measures. Other key information recorded included the main types of mental health concerns, help-seeking behavior, contextual levels (e.g., individual, neighborhood, parent, peer, school), and key findings related to the research questions. The researchers continuously updated the data-charting form in an iterative process. The lead reviewer and other authors discussed the results.

Synthesizing Results

The researchers exported the data-charting form in NVivo into Microsoft Excel for the handling and synthesizing of results. The studies were grouped according to the main types of mental health concerns and help-seeking behavior and summarized according to study population (i.e., sample size, gender, and SES level), age and year level, adolescent developmental stage (i.e., early, middle, or late), recruitment, SES variables and measures, dependent variables (e.g., types of mental health concerns or help-seeking behavior), related context (i.e., individual, parent, school, or peer), and findings related to adolescents in high SES groups that were segmented into positive or protective factors and negative or risk factors. The researchers categorized the studies’ countries according to the World Health Organization Regions (WHO, 2023).

Results

Selection of Sources of Evidence

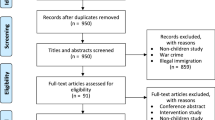

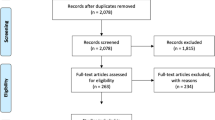

The electronic database search identified a total of 1131 studies, which were screened and assessed for eligibility after duplicates were removed. See Fig. 1 for results of this process, including reasons for exclusions.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for the Scoping Review Process (Page et al. 2021)

Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

Eighty-three studies met the eligibility criteria for this review. Table 2 charts the characteristics, SES types and measures, the mental health concerns and help-seeking behavior, as well as contextual factors, of included studies. Most studies were published between 2015 and 2021 (n = 59; 71.1%). Seventy-two (86.7%) studies were quantitative and of these studies, 62 (74.7%) were cross-sectional and ten (10.8%) longitudinal. There were six (7.2%) qualitative and three (3.6%) mixed methods studies. Sample sizes in the quantitative and longitudinal studies ranged from 88 to 1,405,763, and from 14 to 128 in the qualitative studies.

International Regions

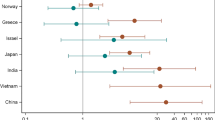

The studies were conducted in 51 (26.3%) of 195 countries globally and in five of the six WHO (2023) regions. Because eight (9.6%) of the 83 studies were cross-national, the greatest number of countries examined in the studies (i.e., countries frequencies; N = 169) were in Europe (n = 117; 69.6%), followed by the Americas (n = 30; 17.9%), and the Western Pacific (n = 14; 8.3%). Few studies were identified from the South-East (n = 6; 3.6%) and Eastern Mediterranean (n = 2; 1.2%), and no studies were identified from Africa. The breakdown of studies according to World Bank Country Income Classifications by income level, is presented in Fig. 2 (World Bank, ). Eighty-three percent of countries examined were classified as having high income levels and only 10.7% and 6.3% were classified as having upper-middle and low middle-income levels respectively, and no studies were conducted in countries with low-income levels.

World Bank Country Income Classifications by Income Level Note. World Bank Country Income Classifications (World Bank, 2023)

Recruitment Settings and Socioeconomic Status Characteristics

Table 3 provides data on recruitment settings and SES characteristics used to examine mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors among adolescents in high SES groups. Eighty-two percent of reviewed studies recruited adolescent participants from schools and national databases on schools. Most studies recruited participants from high, medium and low SES adolescent groups. In addition, a majority of studies recruited from homogenous populations (e.g., Caucasian), and male and female participants, except for 3 (3.6%) studies that included transgender and those not specifying their genders (Choi & Miller, 2018; Delfabbro et al. 2016; Franck et al., 2020). Thirty-four percent of studies concurrently examined early and middle adolescent development stages. Other studies focused on one or a combination of other developmental stages (See Table 3).

Seventeen different methods were reported to classify adolescent SES, with types and measures of adolescent SES being largely heterogenous, except for the Family Affluence Scale (FAS; n = 33, 39.7%; Currie et al., 2008a). The FAS was often used in conjunction with other types of SES measures. For example, in European studies, the FAS was also used as part of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC; n = 12, 14.4%), a WHO cross-sectional and cross-national survey conducted every four years (Currie et al., 2008b; Inchley et al., 2016). Most studies used one type of SES level to identify adolescent SES (n = 41, 49.4%), with the highest frequency being family SES (n = 21, 25.3%). Other SES types used were school SES (i.e., school type or based on high SES neighborhoods), neighborhood SES (identified via census data) and to a lesser extent, family SES measured by parent educational attainment and occupational social status. Three (3.6%) studies also used a subjective social class measure (Alder et al., 2000) that refers to subgroups with similar levels of wealth, influence, and status (Choi & Miller et al., 2018; Sweeting & Hunt, 2014, 2015). Individual (n = 57, 35.6%) and parent factors (n = 31, 19.4%) were the most researched contextual areas across the studies, followed by school (n = 27, 16.9%) and peer (n = 20, 12.5%) contextual factors.

Synthesizing of Results to Address Research Questions

Mental Health Concerns Among Adolescents in High SES Contexts

Studies explored multiple mental health concerns, meaning that the total number of mental health concerns examined exceeded the number of studies included in the review. In order of most researched, the main mental health concerns explored among adolescents in high SES groups (i.e., the most frequent) were substance use (n = 35; 23.8%), externalizing behaviors, risk behaviors and bullying (n = 25; 30.1%), depression (n = 18; 12.2%), and anxiety (n = 16; 10.9%). Other mental health concerns examined were more general internalizing concerns (n = 11; 7.5%); stress (n = 9; 6.1%); adverse circumstances, distress, and negative events (n = 8; 5.4%); and adjustment (n = 6; 7.2%). Ten (6.8%) studies examined general mental health and social emotional concerns. Few studies investigated psychosomatic and somatic complaints (n = 4; 2.7%), psychosis and psychopathology (n = 2; 2.7%), gambling (n = 1; 0.7%), self-harm (n = 2; 1.4%), or suicidality (n = 1; 1.2%).

Substance use. Of the 35 studies that examined substance use concerns, most were conducted in Europe (n = 86; 80.4%) and the Americas (n = 14; 13.1%), with few studies from the Eastern Mediterranean (n = 3; 2.8%), South-East Asia (n = 2; 1.9%), and Western Pacific (n = 2; 1.9%). There were eight cross-national studies on substance use. The types of substance use explored included alcohol use (e.g., binge drinking and intoxication; n = 25; 38.5%), other drug use (e.g., cannabis and cocaine; n = 18; 27.7%), smoking nicotine (n = 17; 26.2%), prescription drug misuse (n = 3; 4.6%), and risks of substance use (n = 2; 3.1%). The review identified no studies that explored vaping among adolescents in high SES groups. Most studies on substance use recruited adolescents in high, medium, and low SES groups (n = 23; 35.4%). Other studies recruited from both boarding schools and day students (n = 6; 9.2%), high SES groups only (n = 4; 6.2%) and high and low SES groups (n = 2; 3.1%). Eleven (31.4%) studies examined early, mid, and late stages of adolescent developmental, while eight studies focused only on mid-adolescence (n = 8; 22.95%). No studies focused specifically on early adolescence.

Alcohol use. Ten studies in Europe, the Americas, and the Western Pacific regions recruited adolescents from high, medium, and low SES groups or high and low SES groups to examine alcohol use. These studies found higher alcohol consumption, binge drinking intoxication, or alcohol misuse among adolescents in high SES groups compared to adolescents in other SES groups (Boricic et al., 2015; Coley et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2015; Lund et al., 2017; Luther et al., 2018; Lyman & Luthar, 2014; Maenhout et al., 2020; Obradors-Rial et al., 2018; Park & Hwang, 2017; Pederson et al., 2015). Individual contributing factors to high levels of alcohol consumption among adolescents in high SES groups were shown to be weekly availability of money, low self-esteem, positive beliefs about the effects of alcohol, low refusal skills, conduct problems and violent behaviors, as well as adolescent social network quality (Mehanovic et al., 2020; Obradors-Rial et al., 2018; Pederson et al., 2015; Sajjadi et al., 2018). Adolescents with high social standing (e.g., popular) were also reported to have higher levels of risky alcohol consumption (Obradors-Rial et al., 2018).

Other contributing contextual factors linked to higher alcohol consumption were school SES (i.e., high SES and boarding capability), attending schools with peers in high SES groups, peer social status, friends’ alcohol use and neighborhood SES (i.e., education, income, and unemployment levels in residential areas; Coley et al., 2018; Lund et al., 2017; Mehanovic et al., 2020; Pederson et al., 2015; Sweeting et al., 2015). Peer alcohol use in high SES schools was shown to influence alcohol consumption more than parental drinking and permissive attitudes toward alcohol use in low SES schools (Mehanović et al., 2020). Similarly, subjective school-based status (SSS) related to peers was positively associated with smoking and drinking, unlike SSS related to academic achievement or sport, which were negatively associated with these substances (Sweeting et al., 2015).

Contextual parenting factors linked with higher alcohol consumption and intoxication were alcohol-related norms in the parental home, parental alcohol consumption and not feeling emotionally close to mothers and fathers, and alcohol access at home (Lyman & Luthar, 2014; Pederson et al., 2015). Furthermore, a qualitative study revealed that adolescents in high SES families related their substance use concerns to family connections, resources, and social backgrounds, and were introduced to substances as early as ten years of age as a family custom (Pfaffendorf, 2019). Contextual parenting factors that protect against higher alcohol consumption were shown to be immigrant background, religious involvement, parental containment (i.e., awareness of adolescent activities), and monitoring of frequency of drinking and alcohol intoxication, as well as parental restrictions related to not drinking at home (Luther et al., 2018; Mehanovic et al., 2020; Pederson et al., 2015). Some parents in high SES groups were also found to impose stricter rules on alcohol use by their children than those in low SES groups (Mehanovic et al., 2020). Other protective factors were school-based social status related to academic achievement and involvement in sports (Sweeting et al., 2015).

Studies on boarding schools demonstrated a higher risk of (monthly) alcohol consumption and intoxication among those who were boarding compared to adolescents who were not boarding (i.e., day students; Noll et al., 2020). This included both school-related and non-school contexts. The median age of first drunkenness was 14 in adolescents in non-denominational boarding schools and 15 in adolescents in religious boarding schools, and both school types were demonstrated to have an earlier onset of substance use compared to other school types (Pfeiffer & Pinquart., 2017a, 2017b). Protective factors were shown to include more positive relationships with peers who never or rarely drank and attending a church-run boarding school (Agmon et al., 2015; Pfeiffer & Pinquart, 2017a, 2017b).

Illicit drug use. Findings were mixed for illicit drug use. One study found insufficient evidence of a strong relationship at an individual level with declining SES and illicit substance use (Kipping et al., 2015). Two studies found adolescents in low SES groups had higher rates of illicit drug use (Bogt et al., 2014; Gauffin et al., 2013). For example, a large study in Sweden (n = 1,405,763) found adolescents from households of the lowest SES had a more than twofold increased risk of developing illicit drug problems in contrast to adolescents raised in families of high SES (Gauffin et al., 2013). Yet, the study demonstrated a strong association among adolescents from high SES families between school failure and drug problems and identified an increase in school failure corresponding to higher SES (Gauffin et al., 2013). Adolescents attending boarding schools or schools with peers of higher SES were shown to be associated with greater levels of illicit drug use compared to other adolescent groups (Coley et al., 2018; Noll et al., 2020). Bogt et al. (2014) examined cannabis use in 30 countries in Europe and the Americas and found that cannabis use was less characteristic of high gross domestic product (GDP) countries than lower GDP countries.

Smoking nicotine or cigarettes. There were inconsistent findings on smoking among adolescents in high SES groups. The risk of current smoking was found to be higher in adolescents in high SES groups compared to those in low and middle SES groups and schools (Noll et al., 2020; Park & Hwang, 2017). However, adolescents in the low SES groups were shown to face lower risks of smoking compared to those in high SES groups in countries such as Indonesia and the United Kingdom (Kusumawardani et al., 2018; Sweeting et al., 2015). Other studies found no significant differences in smoking between adolescents of low–medium and high family affluence (Maenhout et al., 2020). A cross-national study of 35 countries in Europe and North America found country-level differences in smoking prevalence in adolescent populations between adolescents of high and low SES and these differences were greater in high SES countries (Pförtner et al., 2015a). Protective factors associated with a lower likelihood of smoking included social capital (i.e., social networks of relationships) related to voluntary organizations, trust and reciprocity in family, neighborhood, and school, but not friend-related social capital (Pförtner et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Externalizing behaviors, risk behaviors and bullying. Twenty-five studies examine externalizing behaviors, risk behaviors and bullying mainly in Europe (n = 10, 40.0%) and the Americas (n = 10; 40.0%). The review identified few studies in the Eastern Mediterranean (n = 1; 4.0%) and Western Pacific (n = 3; 12.0%). There was one cross-national study in the Region of the Americas and Western Pacific (n = 1, 4.0%). No studies are identified in South-East Asia or Africa. Most studies were quantitative (n = 20, 80.0%) and others were mixed methods (n = 1; 3.8%; Agmon et al., 2015) and longidtudial studies (n = 4, 16.0%; Ansary et al., 2017; Buffarini et al., 2020; Hartas & Kuscuoglu, 2020; Kipping et al., 2015).

Conduct issues, bullying and delinquent behavior were identified among adolescents in high SES groups (Ansary et al., 2017; Coley et al., 2018; Lester et al., 2015; Lund & Dearing, 2012). Individual factors associated with risky behavioral concerns included higher alcohol consumption compared to peers in other SES groups (Agmon et al., 2015; Lund et al., 2017). Adolescents attending schools with peers of higher SES were more frequently associated with conduct concerns, unlike those from other adolescent groups of different SESs (Coley et al., 2018). In addition, bullying was found in boarding schools, with adolescents residing in boarding schools experiencing significantly higher levels of victimization and perpetration of bullying behaviors after transition to boarding school than non-boarders (Lester et al., 2015). Adolescent boys residing in high SES neighborhoods were approximately two times more likely to report high levels of delinquent behavior compared to adolescent boys residing in medium SES neighborhoods. Moreover, delinquency levels among adolescent boys in high SES families were lowest when residing in neighborhoods of medium SES. Lund et al. (2017) found family affluence (or lack thereof) to be a risk factor for conduct problems among adolescents at the highest and lowest income distributions. Family stress and adolescent problem behaviour were also demonstrated to operate differently in low, middle and high-income families based on specific parental factors (e.g., parent depressive symptoms, interpersonal conflict and positive parenting; Ponnet et al., 2014).

Anxiety, depression, and stress. Twenty-three (27.7%) studies examined anxiety, depression or stress in the Americas (n = 8, United States), Europe (n = 6; Belgium, Croatia, Hungary, Norway, Slovenia), the South-East (n = 3; India, Indonesia, Nepal), and the Western Pacific (n = 6; Australia, China, Malaysia). Of these studies, specific areas of investigation were anxiety (n = 3); anxiety, depression, and stress (n = 5); anxiety and depression (n = 7); depression (n = 3); depression and stress (n = 1); and stress (n = 4). Eleven studies specifically recruited adolescents from high SES groups to investigate anxiety, depression, and stress. Anxiety and depression were identified as key mental health concerns and, to a lesser extent, was stress (Ansary et al., 2017; Luthar & Barkin, 2012). Individual factors that were linked to significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety among high SES adolescents included receiving extra tuition, reporting parental pressure to study, and holding beliefs that success was determined by their ability relative to others (e.g., higher ego orientation; Ansary et al., 2017; Luthar & Barkin, 2012; Travers et al., 2013). Lower academic grades or failure in high SES groups were associated with significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (Ansary et al., 2017; Bhasin et al., 2010; Luthar & Barkin, 2012). Individual characteristics, such as higher ego orientation, coincided with the reporting of more anxiety and depressive symptoms (Travers et al., 2013). Other individual factors related to high levels of stress were lack of sleep (i.e., approximately two hours less than the recommended nine hours) and pervasive pressure to perform (De Silva-Mousseau et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2018). Moreover, depression and stress were positively and significantly associated with the number of adverse events that had occurred in an adolescent’s life in the past 12 months (Bhasin et al., 2010).

Contextual factors of parenting that were demonstrated to significantly increase levels of depression, anxiety, and stress were parental pressure to study, conflict between parents, or a parent who inflicted physical violence (Luthar & Barkin, 2012). Other contributing parent- and peer-related factors identified in a qualitative study were misaligned expectations in parent and adolescent relationships and peer competition; both were linked to higher levels of stress among adolescent girls in single-sex schools, and to peer competition (Spencer et al., 2018). In these studies, recruiting only from high SES groups, parental contributing factors shown to negatively affect depression, anxiety, or stress were mainly related to parent involvement in the academic achievement of adolescents and parental criticism. For example, Williams et al. (2018) found that parental criticism was significantly and positively associated with perceived stress levels. Moreover, if parents were involved in the organized activities of adolescents, these adolescents were shown to experience marginally greater anxiety symptoms than adolescents who participated in these activities for intrinsically motivated reasons (Randall et al., 2016). A number of protective factors against anxiety, depression, and stress were found to be related to individuals, parents, or peers. Protective parenting factors included adolescents’ capacity to discuss personal problems with their parents (Luthar & Barkin, 2012).

Nine studies recruited adolescents from different SES groups or used national data (e.g., sourced from Health & Behavior Children’s Surveys [HBCS]; Currie et al., 2014) to investigate anxiety, depression, and stress (Kiang et al., 2020; Lund & Dearing, 2012). In these comparative studies, individual (i.e., gender) and neighborhood contextual factors were evident, with girls in high SES neighborhoods in the United States reporting higher levels of anxiety and depression than those in middle-class neighborhoods. Further, girls’ anxiety and depression levels were lowest for those in high SES families living in middle-class neighborhoods (Lund & Dearing, 2012). Peer competition and envy were associated with high stress levels (Lyman & Luthar, 2014; Spencer et al., 2018). Protective parenting factors identified were consistent paternal discipline and monitoring of behavior, which were found to reduce adolescent anxiety in high SES families (Jafari et al., 2016).

Three studies recruited adolescents from boarding schools and demonstrated significant levels of anxiety, depression, or stress (Gao et al., 2021; Mander et al., 2015; Wahab et al., 2013). Academic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal relations, teaching, and peer group challenges were the individual and contextual factors contributing to these mental health concerns. Life events and the ongoing challenges related to the transition to boarding school were other individual factors significantly correlated with depression among boarding students, with Grade 8 boarding students reporting significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (Gao et al., 2021; Mander et al., 2015).

Help-seeking Behavior Among Adolescents in High Socioeconomic Status Groups

Nineteen (22.9%) studies explored help-seeking behavior in the Western Pacific (n = 6; 31.6%), Europe (n = 5; 26.3%), and the Americas (n = 5; 26.3%). Few studies were conducted in the Eastern Mediterranean (n = 1; 5.2%) or South-East Asia (n = 2; 10.5%). Of these studies, 13 (68.4%) were quantitative, four (44.4%) qualitative and two (10.5%) mixed-methods. Seven (36.8%) of the studies focused on boarding schools (Agmon et al., 2015; Franck et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2021; Lester et al., 2015; Sari et al., 2019). According to the Rickwood et al. (2012) model, three (out of four) sources of help-seeking dimensions examined were formal (i.e., professionals and nurses), semi-formal (e.g., school staff who do not have a specific role in delivery of mental health care) and informal (i.e., seeking assistance from social networks including family and peers). There were no studies on self-help resources (Rickwood et al., 2012). Most formal help-seeking dimensions investigated related to school-based interventions and support at school, while informal sources were centered on peer support. Of concern, mentors in boarding schools were reported to instruct adolescents to hide smoking and alcohol from plain view, without trying to decrease their use (Agmon et al., 2015). Specific to bullying involving cyberhate, differences were found between SES groups on the type of informal help-seeking advice that they received from peers with distal advice (e.g., go to the police) and technical coping (e.g., “… block that person so that he/she cannot contact me anymore”) being higher among adolescents in lower SES groups, compared with adolescents in higher SES groups (Wachs et al., 2020).

Three out of five types of help-seeking support investigated affiliative support (i.e., peer support), emotional support (for emotional wellbeing) and treatment (i.e., treatment or therapy; Rickwood et al., 2012). No studies were found on instrumental support (i.e., financial and transport) and informational support (i.e., health related and referral information; Rickwood et al., 2012). Five studies investigated affiliative support (e.g., peer support) among adolescents in high SES groups for depression and bullying (Gao et al., 2021; Sajjadi et al., 2018; Wachs et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2017). Overall, these studies demonstrated that affiliative support reduced levels of depression among adolescents in high SES groups, particularly adolescents at boarding schools (Gao et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2017). Interventions were also found within boarding schools (e.g., cognitive therapy), particularly for externalising behaviour such as bullying (Sari et al., 2019). Significant differences were found between household income and health services accessed among youth in low and medium SES households who utilised more health and school services and had higher rates of 12-month service use compared to youth in high SES households (Vu et al., 2018). Several studies also investigated school-based interventions in boarding schools involving nurses, counsellors and staff in program delivery (Franck et al., 2020; Pavletic et al., 2016).

Barriers to seeking help and not seeking help were explored in the literature. Specific to bullying in boarding schools, Lester et al (2015) found adolescents in grades 7 and 8 who witnessed peers being bullied helped, however by grade 9, most adolescents who witnessed others being bullied, did not intervene. Over one-quarter of boarding adolescents who reported experiences of being bullied did not seek help (Lester et al., 2015). Other barriers to help-seeking behaviors related to parent contextual factors such as parental power (e.g., holding prominent community and professional positions), ability to terminate treatment and financial ability to litigate (Bernard, 2018; Golightly et al., 2020). Subjective social class (e.g., individual perceptions of their position within a social class hierarchy compared to others; Alder et al., 2000) was demonstrated to be a significant indirect pathway from objective social class (e.g., using family SES or education levels) to attitudes toward seeking professional help (Choi & Miller, 2018). Other studies highlighted the difficulty experienced by social workers, not adolescents directly, when working with parents in high socioeconomic-level contexts in neglect cases (Bernard, 2018).

Discussion

Adolescents in high SES groups are emerging as an important subgroup at risk of some mental health concerns, and there is a critical need to consolidate current knowledge about these concerns and how they seek help. This scoping review aimed to synthesize empirical literature on mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors among adolescents in high SES groups, according to the PRISMA guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018).

The main review finding is how adolescents in high SES groups face significant mental health concerns related to substance use, a phenomenon observed across cultures (i.e., Eastern and Western) and countries (Dierckens et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2015). Other reported mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups included externalizing and risk behaviors, bullying, depression, anxiety, and stress (Lund et al., 2017; Luthar & Barkin, 2012). Albeit in a limited way, adverse and stressful life events, internalizing problems and prescription misuse were also identified as mental health concerns experienced by adolescents in high SES groups (Ajduković et al., 2018; Kirkeby et al., 2014; Runarsdottir et al., 2019).

Alcohol use was the most researched mental health concern in the review with evidence demonstrating adolescents in high SES groups engaged in higher levels of alcohol use and intoxication, reported an earlier onset of drinking, more frequent intoxication and drunkenness, and risky alcohol consumption (e.g., binge drinking), compared to adolescents in other SES groups (Lu et al., 2015; Noll et al., 2020; Park & Hwang, 2017). Adolescents in high SES neighborhoods may also be more likely to experience more alcohol-related problems at a population level given the higher prevalence of alcohol use (Pedersen et al., 2015). A potential reason for higher alcohol consumption among adolescents in high SES groups may relate to the importance of subjective social class and social influence in high SES contexts (Gray & Squeglia, 2018; Knoll et al., 2015). For example, peers were found to play an influential role with alcohol consumption among adolescents in high SES groups and were more influenced by their friends’ alcohol use than adolescents in low SES groups, who were more affected by parental drinking behaviour (Mehanvoic et al., 2020). Adolescents in high SES groups have also been shown to have greater access to financial resources (e.g., pocket money) compared to other SES groups (Obradors-Rial et al., 2018).

Other substance use concerns identified in this review related to illicit drug use (e.g., cannabis, cocaine, and stimulants), smoking (e.g., tobacco) and other risk-taking behaviors (Coley et al., 2018; Luthar et al., 2018). Surprisingly, these risks could be up to two to three times higher than for same-aged peers in other socioeconomic groups and may also continue into adulthood (Luthar et al., 2018). However, findings were mixed on the level of illicit drug use and smoking among adolescents in high SES groups (Gauffin et al., 2013; Kipping et al., 2015). This may be due to friend-related social capital (e.g., friendship groups) and objective social class (e.g., popularity) that has been shown to play an influential role in smoking among adolescents in high SES groups compared to other SES groups (Pförtner et al., 2015a, 2015b). Other potential reasons relate to country-specific (i.e., national) legislation and international regulations on illicit drug use and tobacco to curb consumption leading to differences in prevalence rates between countries (Degenhardt et al., 2019; Kilmer et al., 2015).

More broadly across studies in this review, alcohol and illicit drug use among adolescents was associated with higher family SES, while smoking was associated with lower family SES (Lu et al., 2015; Noll et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2012). One explanation for these discrepancies may relate to studies examining general illicit drug use rather than specific types of illicit drugs (e.g., cannabis, cocaine). Country-specific differences were also observed for illicit drug use between adolescents in high, medium, and low SES groups (Bogt et al., 2014). For example, cannabis was found to be less characteristic in high GDP countries compared to lower GPD countries (Bogt et al., 2014). Early onset adolescent substance use has been suggested to affect brain development and academic achievement, as well as increase the risk of later mental health and substance use disorders (Lubman et al., 2007; Meier et al., 2015; Squeglia et al., 2014). As such, it is important to develop a clearer understanding of the specific types of substances used among this subgroup in order to develop targeted prevention and early intervention approaches.

Review findings suggest that parents, school types, neighborhood SES, and peers play a crucial role in influencing the mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups, rather than family SES alone (Luthar & Barkin, 2012; Morgan et al., 2019; Wahab et al., 2013). A key area explored was the impact of the parent–adolescent relationship (Damsgaard et al., 2014; Stiles et al., 2020). Excessive parental pressure to perform was associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress (Luthar & Barkin, 2012; Randell et al., 2016). According to Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, adolescents typically begin to depart from their parental influences and to define and establish their own sense of self and personal identity during this important developmental stage (Erikson, 1968; Schachter & Galliher, 2018). However, exigent parental expectations to perform academically and other forms of parental criticism may interfere with the development of their identity and sense of self as well as being a risk factor for mental health concerns (Lareau, 2011; Spencer et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2018).

More broadly to this review, pressures to succeed have been linked to detrimental mental health concerns (such as suicide) among adolescents in high SES groups (DeHann, 2016; Levine, 2006). Some adolescents have also reported feelings of alienation from their parents and this was associated with higher substance use (Lyman & Luthar, 2014). Other reviewed studies have shown parents in high SES groups to have low levels of containment of adolescent substance use, as well as easy access to alcohol in the parents’ homes, permissive norms regarding alcohol at home and alcohol consumption among parents (Pedersen et al., 2015; Pfaffendorf, 2019). Conversely, protective factors against substance use were parent containment of adolescent substance use and discussing problems with parents (Luthar et al., 2018; Mehanovic et al., 2020). Broader literature on parent–child relationship quality, parent support, and parental involvement have been identified as protective and modifiable parenting factors for adolescent alcohol misuse (Ryan et al., 2010). Therefore, parent psychoeducation on how to increase support in these areas is crucial in high SES groups.

High neighborhood SES was also found to influence the development of mental health concerns (e.g., anxiety and depression; Lund et al., 2017). Surprisingly, adolescents in high SES families that live in middle SES groups may be at lower risk of delinquency for boys and anxiety and depression for girls than their counterparts of the same SES living in high SES neighborhoods (Lund & Dearing., 2012). This suggests that living in middle-class areas may be a protective factor for adolescents in high SES families. However, other studies found family-based and individual factors, and not neighborhood factors, were associated with high alcohol use and intoxication among adolescents in high SES neighborhoods compared to adolescents in other SES groups, highlighting mixed results on the effects of neighborhood SES (Pedersen et al., 2015). This is aligned with broader examination of neighborhood SES, with a systematic review also finding mixed results on the effects of neighborhood-level SES on adolescent alcohol use (Jackson et al., 2014). Jackson et al. (2014) suggest that neighborhood contexts are considered from the outset of study design and examined with other individual-level variables to isolate neighborhood effects and better understand mediating factors on alcohol use. Future studies examining the influence of neighborhood contexts are therefore warranted.

The synthesized evidence also suggests that the type of school plays an influential role in mental health concerns among high SES groups (e.g., private, independent, boarding, day or religious schools; Pfeiffer & Pinquart., 2017a, 2017b; Sweeting & Hunt, 2014). For example, higher alcohol consumption and intoxication was linked to high SES schools, and attending schools with peers of high SES was associated with a higher likelihood of intoxication, drug use, and externalizing behaviors than adolescents in day schools and in other SES groups (e.g., Coley et al., 2018; Lund et al., 2017). Adolescents attending boarding schools were found to have significantly higher levels of alcohol use, earlier onset of alcohol use, higher degrees of victimization and perpetration of bullying behaviors, greater emotional difficulties, and other mental health concerns (e.g., depression and anxiety; Lester et al., 2015; Mander et al., 2015). These risks may be influenced by free time with peers in boarding schools, which may strongly predict adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking (Pfeiffer & Pinquart, 2017a, 2017b). Adolescents in high SES groups with low levels of academic achievement or instances of failure were another at-risk group who may be more vulnerable to specific mental health concerns (e.g., substance use) than those with strong academic performance in high SES schools and adolescents with low levels of academic achievement in other SES groups (Bhasin et al., 2010; Gauffin et al., 2013).

Peers were also found to play an influential role in mental health concerns among high SES groups (Agmon et al., 2015; Morgan et al., 2019; Nagy–Penzes, 2020). Peer competition and envy were associated with high-stress levels and other mental health concerns (Lyman & Luthar, 2014; Spencer et al., 2018). Surprisingly, subjective school-based status (SSS) related to peers within the high SES group was positively associated with smoking and heavier alcohol use compared to SSS related to scholastic or sporting activities, which were in fact negatively associated with consumption of these substances (Sweeting et al., 2015). SSS peers relates to an adolescent’s subjective sense of place within a social hierarchy (Goodman et al., 2001). One explanation for these findings relates to a neurobiological perspective, with adolescent brain development strongly oriented towards and particularly susceptible to the social influence of peers (Telzer et al., 2018). More widely related to social hierarchies, school-based peer hierarchies are found to be more important than family SES for mental health concerns (e.g., stress; West et al., 2009). This suggests it is important for future studies to examine mediating effects of SES, subjective school-based status and subjective social class concurrently to determine mediating SES factors on the mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups.

Review findings suggest the evidence base for help-seeking behavior among adolescents in high SES groups is in its infancy. Formal (e.g., school-based interventions) and informal sources (e.g., peers) were main sources of help-seeking found for mental health concerns, such as bullying, depression, anxiety and substance use, albeit limited (Pavletic et al., 2016; Sari et al., 2019). Types of help-seeking support investigated are affiliative support (e.g., peer support), emotional support and treatment (Gao et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2020). Interestingly, differences were found in health service use between adolescents in low and medium households, compared to adolescents in high SES groups and not for access to school or telephone services (Vu et al., 2018). Other differences between adolescents in high SES groups and adolescents in other SES groups were demonstrated, with peer support for cyberhate bullying among adolescents in high SES groups being shown to have lower levels of providing distal advice (e.g., notifying police) and technical coping (e.g., blocking on social media; Wachs et al., 2020). Specific to bullying in boarding schools, most adolescents in grade 9 who witnessed others being bullied, reported not helping and approximately 25% of boarding adolescents who reported experiences of being bullied did not seek help (Lester et al., 2015). These findings align with earlier research documenting a culture among high SES families that may deter this subgroup from seeking help due to valuing privacy, particularly when their parents may hold powerful societal positions, however further exploration is warranted (Luthar, 2003).

Surprisingly, there was scant evidence identified on help-seeking behaviour for substance use, particularly alcohol, representing a critical gap. Generally, schools and peers can not only play a major role in influencing mental health concerns, but also in promoting help-seeking for mental health concerns, as demonstrated by school-based interventions and peer support programs (Cheetham et al., 2017). Schools and peers can also be first line responders to mental health concerns, and adolescents can play a central role in supporting effective prevention and early intervention efforts (Cheetham et al., 2017). No interventions targeting this subgroup of adolescents were found, aside from boarding school programs related to Indigenous and social and emotional well-being (Pavletic et al., 2016) and cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety in adolescents in the early prodromal of psychosis (Sari et al., 2019). Specific interventions are required to accommodate the differences in mental health concerns and the influencing contextual factors that are pertinent to adolescents in high SES groups (Lester et al., 2015). Potential opportunities remain to harness and leverage the highly influential role of peers among adolescents in high SES groups to address mental health concerns, particularly for alcohol use, by engaging peers in targeted prevention and early interventions efforts.

Limitations of Reviewed Studies

Key limitations of reviewed studies relate to the diverse and inconsistent methods used to measure SES (e.g., household income, parent education, neighbourhood and school) and the types of recruitment for adolescents in high SES groups. For example, some studies that recruited from different SES groups (i.e., not only high SES) found neighbourhood SES impacted adolescent mental health concerns in the high SES group to a greater extent than low and medium SES groups (Coley et al., 2018; Lund & Dearing, 2012). However, other studies found school SES was associated with higher risk of mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups rather than neighborhood or family SES (Lund et al., 2017; Sweeting et al., 2015). Other studies indicated a strong relationship between subjective SES and family affluence (i.e., high SES) and not residential deprivation (Sweeting et al., 2015). Several studies in this review examined multi-level objective and subjective SES variables and similar studies are needed to expand the international evidence base (Dierckens et al., 2020; Sweeting et al., 2015).

Most reviewed studies conducted in the United States used school samples (Ciciolla et al., 2017). Conversely, in Europe, reviewed studies drew on nationally representative populations from adolescents across SES groups and, therefore, may be more representative of the specific mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups compared to adolescents in other SES groups (Morgenstern et al., 2013). In addition, objective social class was also shown to have stronger associations with, for example, substance use, compared to objective social class. Thus, this makes it difficult to identify the extent to which each high SES contextual factors contribute to specific mental health concerns among adolescents in high SES groups. As such, formally comparing results across studies is challenging (Reis, 2013). Further complexities relate to the differences found with specific mental health concerns between countries, such as substance use, among high SES groups. One explanation may relate to the GDP levels of countries (i.e., country SES) and also national education systems (Kraus et al., 2018; WHO, 2020).

Limitations of the Review

A limitation of the review is the risk of reporting bias, with only studies in English included. However, cross-national studies on mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviours were included. An optional critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence from included review studies was also not included (see Item 19; Tricco et al., 2018).

Future Research Directions

Foremost, review findings underscore the need to concurrently examine multi-level SES factors when exploring mental health concerns and help-seeking behaviors among adolescents in high SES groups (Elgar et al., 2013; Lund et al., 2017). Specifically, objective SES measures, subjective social class of adolescents among peers (e.g., MacArthur Subjective SES Scale; Alder 2000), subjective school-based status and multi-level contextual factors (Coley et al., 2018; Sweeting et al., 2015). Consistent use of age levels in future research, specific to early, middle, and late adolescent developmental stages, may also inform more targeted and age-appropriate approaches to mental health risks in prevention and early intervention efforts (Department of Health, 2019). The review also identified international geographical gaps in the field. Evidence has emerged mainly from Europe and the Americas and research is needed in other international regions. At the macro level, country wealth may play a systemic role in influencing mental health concerns among adolescents in high socioeconomic-level groups (Dierckens et al., 2020). Therefore, it is also prudent to consider country GDP, particularly in cross-national studies (Elgar et al., 2013; Lenthe et al., 2021). More studies are also needed at a country level to explore the potential influence of country policy on, for example, substance use (Ryan et al., 2010).

Future research is required on other mental health concerns such as vaping and other specific types of illicit drug use (e.g., cannabis and cocaine) among adolescents in high SES groups. Vaping is a recent phenomenon and research is urgently needed to inform prevention and early intervention efforts (Kim et al., 2022). Furthermore, research on help-seeking behavior among these adolescents is lacking, and little is known about their lived experiences of seeking help, particularly for the main mental health concerns identified in this review (i.e., substance use, externalizing behaviors, depression, anxiety and stress). To address this lack of evidence, drawing from the broad literature on help-seeking behavior among adolescents, replicating studies, and conducting longitudinal studies that explore the discourse of mental health concerns can extend the evidence-base and inform targeted intervention approaches.

Conclusion

Research on mental health concerns and help-seeking behavior among adolescents in high SES groups is emerging. Review findings suggest these adolescents face heightened risks of alcohol misuse, externalizing and risk behaviors, bullying, depression, anxiety, stress, and further, that their help-seeking behaviors for these concerns remains unclear. Other key review findings pertain to parents, school, peers and residing neighborhoods as contributing contextual factors influencing these mental health concerns. Subgroups are also identified among adolescents within high SES groups who face heightened risks of specific mental health issues compared to other high SES peers, such as adolescents residing in boarding schools, those with high subjective social class and those with poor academic achievement or failure. Given adolescence is a critical time for prevention and early intervention, further research and targeted approaches are warranted for the mental health concerns of adolescents in high SES groups to support their transition to adulthood.

Data Availability

Data supporting the results are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

*Studies included in the scoping review

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy White women. Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586

*Agmon, M., Zlotnick, C., & Finkelstein, A. (2015). The relationship between mentoring on healthy behaviors and well-being among Israeli youth in boarding schools: A mixed-methods study. BMC Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0327-6

*Ajduković, M., Bulat, L. R., & Sušac, N. (2018). The internalising and externalising problems of adolescents in Croatia: Socio-demographic and family victimisation factors. International Journal of Social Welfare. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12284

Ajdukovic, M., & Bulat, L. R. (2012). Perception of family financial status and high school students’ psychosocial functioning. Revija Za Socijalnu Politiku. https://doi.org/10.3935/rsp.v19i3.1075

*Akiyama, T., Win, T., Maung, C., Ray, P., Sakisaka, K., Tanabe, A., Kobayashi, J., & Jimba, M. (2013). Mental health status among Burmese adolescent students living in boarding houses in Thailand: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-337

Ames, C. (1995). Achievement goals, motivational climate, and motivational processes. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 161–176). Human Kinetics Books.

*Ansary, N. S., McMahon, T. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2017). Trajectories of emotional–behavioral difficulty and academic competence: A 6-year, person-centered, prospective study of affluent suburban adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000110

Ashiabi, G. S., & O’Neal, K. K. (2015). Child social development in context. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015590840

*Auger, N., Lo, E., Cantinotti, M., & O’Loughlin, J. (2010). Impulsivity and socio-economic status interact to increase the risk of gambling onset among youth. Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03100.x

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. (2022). Australian Health 2022: Data insights, catalogue number AUS 240, Australia’s Health Series Number 18. AIHW, Australian Government. https://doi.org/10.25816/ggvz-vr80

Baum, F. E., & Ziersch, A. M. (2003). Social capital. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.5.320

*Bernard, C. (2018). Recognizing and addressing child neglect in affluent families. Child & Family Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12619

*Bhasin, S. K., Sharma, R., & Saini, N. K. (2010). Depression, anxiety and stress among adolescent students belonging to affluent families: A school-based study. Indian Journal Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-009-0260-5

Bogard, K. L. (2005). Affluent adolescents, depression, and drug use: The role of adults in their lives. Journal of Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.08.8

*Boricic, K., Simic, S., & Eric, J. M. (2015). Demographic and socio-economic factors associated with multiple health risk behaviours among adolescents in Serbia: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1509-8

Bortoli, L., Bertollo, M., & Robazza, C. (2009). Dispositional goal orientations, motivational climate, and psychobiosocial states in youth sport. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(1), 18–24.

Boyce, W., Torsheim, T., Currie, C., & Zambon, A. (2006). The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: Validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-1607-6

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Six theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues (pp. 187–249). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bronk, K. C., & Finch, W. H. (2010). Adolescent characteristics by type of long-term Aim in life. Applied Developmental Science. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690903510331

*Buffarini, R., Abdalla, S., Weber, A. M., Costa, J. C., Menezes, A. M. B., Gonçalves, H., Wehrmeister, F. C., Meausoone, V., Darmstadt, G. L., & Victora, C. G. (2020). The intersectionality of gender and wealth in adolescent health and behavioral outcomes in Brazil: The 1993 Pelotas birth cohort. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.029

Cheetham, A., & Lubman, D. I. (2017). The role of peers in school-based prevention programs targeting adolescent substance use. Current Addiction Reports, 4, 379–385.

*Choi, N.-Y., & Miller, M. J. (2018). Social class, classism, stigma, and college students’ attitudes toward counseling. The Counseling Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018796789

*Ciciolla, L., Curlee, A. S., Karageorge, J., & Luthar, S. S. (2017). When mothers and fathers are seen as disproportionately valuing achievements: Implications for adjustment among upper middle class youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0596-x

*Coley, R. L., Sims, J., Dearing, E., & Spielvogel, B. (2018). Locating economic risks for adolescent mental and behavioral health: Poverty and affluence in families, neighborhoods, and schools. Child Development. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12771

Cummings, C. M., Caporino, N. E., & Kendall, P. C. (2014). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034733

Currie, C. E., Elton, R. A., Todd, J., & Platt, S. (1997). Indicators of socioeconomic status for adolescents: The WHO health behaviour in school-aged children survey. Health Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/12.3.385

Currie, C., Molcho, M., Boyce, W., Holstein, B., Torsheim, T., & Richter, M. (2008a). Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.024

Currie, C., Nic Gabhainn, S., Godeau, E., Roberts, C., Smith, R., et al. (2008b). Inequalities in young people’s health: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children international report from the 2005/2006 survey. World Health Organization.

Currie, C., Inchley, J., Molcho, M., Lenzi, M., Veselska, Z., & Wild, F. (2014). Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2013/14 Survey. CAHRU: Andrews.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., et al. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. In Health policy for children and adolescents (No. 6). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

*Damsgaard, M. T., Holstein, B. E., Koushede, V., Madsen, K. R., Meilstrup, C., Nelausen, M. K., Nielsen, L., & Rayce, S. B. (2014). Close relations to parents and emotional symptoms among adolescents: Beyond socio-economic impact? International Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0600-8

Degenhardt, L., Bharat, C., Glantz, M. D., Sampson, N. A., Scott, K., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Andrade, L. H., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., Bunting, B., de Girolamo, G., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Harris, M. G., He, Y., de Jonge, P., Karam, E. G., et al. (2019). WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators The epidemiology of drug use disorders cross-nationally Findings from the WHO’s World Mental Health Surveys. International Journal Drug Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.002

DeHaan, T.J. (2016). Dying to Succeed A Qualitative Content Analysis of Online News Reports About Affluent Teen Suicide Clusters. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing

*Delfabbro, P. H., Malvaso, C., Winefield, A. H., & Winefield, H. R. (2016). Socio-demographic, health, and psychological correlates of suicidality severity in Australian adolescents. Australian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12104

Department of Health. (2019). National Action Plan for the Health of Children and Young People. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/4815673E283EC1B6CA2584000082EA7D/$File/FINAL%20National%20Action%20Plan%20for%20the%20Health%20of%20Children%20and%20Young%20People%202020-2030.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2022

*DeSilva Mousseau, A. M., Lund, T. J., Liang, B., Spencer, R., & Walsh, J. (2016). Stressed and losing sleep: Sleep duration and perceived stress among affluent adolescent females. Peabody Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1227186

*Dierckens, M., Weinberg, D., Huang, Y., Elgar, F., Moor, I., Augustine, L., Lyyra, N., Deforche, B., De Clercq, B., Stevens, G. W. J. M., & Currie, C. (2020). National-level wealth inequality and socioeconomic inequality in adolescent mental well-being: A time series analysis of 17 Countries. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.009

Divin, N., Harper, P., Curran, E., Corry, D., & Leavey, G. (2018). Help-seeking measures and their Use in adolescents: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0078-8

*Duinhof, E. L., Smid, S. C., Vollebergh, W. A. M., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Immigration background and adolescent mental health problems: The role of family affluence, adolescent educational level and gender. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01821-8

*Elgar, F. J., Trites, S. J., & Boyce, W. (2010). Social capital reduces socio-economic differences in child health: Evidence from the Canadian health behaviour in school-aged children study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101, S23–S27.

*Elgar, F. J., De Clercq, B., Schnohr, C. W., Bird, P., Pickett, K. E., Torsheim, T., Hofmann, F., & Currie, C. (2013). Absolute and relative family affluence and psychosomatic symptoms in adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.030

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Journal of Extension, 6(4).

*Franck, L., Midford, R., Cahill, H., Buergelt, P. T., Robinson, G., Leckning, B., & Paton, D. (2020). Enhancing social and emotional wellbeing of aboriginal boarding students: Evaluation of a social and emotional learning pilot program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030771

*Gao, J.-L., Wang, L.-H., Yin, X.-Q., Hsieh, H.-F., Rost, D. H., Zimmerman, M. A., & Wang, J.-L. (2021). The promotive effects of peer support and active coping in relation to negative life events and depression in Chinese adolescents at boarding schools. Current Psychology, 40, 2251–2260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0143-5

*Gauffin, K., Vinnerljung, B., Fridell, M., Hesse, M., & Hjern, A. (2013). Childhood socio-economic status, school failure and drug abuse: A Swedish national cohort study. Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12169

*Golightley, S. (2020). Troubling the ‘troubled teen’ industry: Adult reflections on youth experiences of therapeutic boarding schools. Global Studies of Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619900514

Goodman, E., Adler, N. E., Kawachi, I., Frazier, A. L., Huang, B., & Colditz, G. A. (2001). Adolescents’ perceptions of social status: Development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics (evanston). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.2.e31

Gray, K. M., & Squeglia, L. M. (2018). Research review: What have we learned about adolescent substance use? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12783

Haagenars, A., de Vos, K., & Zaidi, M. (1994). Poverty statistics in the Late 1980s: Research based on micro-data. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

*Hartas, D., & Kuscuoglu, A. (2020). Teenage social behaviour and emotional well-being: The role of gender and socio-economic factors. British Journal of Special Education. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12328

Hartley, J. E. K., Levin, K., & Currie, C. (2016). A new version of the HBSC Family Affluence Scale - FAS III: Scottish qualitative findings from the international FAS development study. Child Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9325-3

Haselschwerdt, M. L., & Hardesty, J. L. (2017). Managing secrecy and disclosure of domestic violence in affluent communities. Journal of Marriage and Family. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12345

Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Young, T.; Samdal, O.; Torsheim, T.; Auguston, L.; Mathison, F.; Aleman-Diaz, A.; Molcho, M.;Weber, M., et al. (2016) Growing up unequal: Gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being. In Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report From the 2013/2014 Survey; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark.

Irteja, I. M., Yunus, F. M., Isha, S. N., Kabir, E., Khanam, R., & Martiniuk, A. (2022). The gap between perceived mental health needs and actual service utilization in Australian adolescents. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09352-0

Jackson, N., Denny, S., & Ameratunga, S. (2014). Social and socio-demographic neighborhood effects on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of multi-level studies. Social Science Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.004

*Jafari, M., Baharudin, R., & Archer, M. (2016). Fathers’ parenting behaviors and Malaysian adolescents’ anxiety: Family income as a moderator. Journal of Family Issues. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13513580

*Kiang, L., Folmar, S., & Gentry, K. (2020). “Untouchable”? social status, identity, and mental health among adolescents in Nepal. Journal of Adolescent Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558418791501

Kilmer, B., Reuter, P., & Giommoni, L. (2015). What can be learned from cross-national comparisons of data on illegal drugs? Crime & Justice, 44(1), 227–296.

Kim, H., Munson, M. R., & McKay, M. M. (2012). Engagement in mental health treatment among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558418791501

Kim, J., Lee, S., & Chun, J. (2022). An international systematic review of prevalence, Risk, and protective factors associated with young people’s E-cigarette use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811570

*Kipping, R. R., Smith, M., Heron, J., Hickman, M., & Campbell, R. (2015). Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and socio-economic status: Findings from a UK birth cohort. European Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558418791501

*Kirkeby, M. J., Hansen, C. D., & Andersen, J. H. (2014). Socio-economic differences in use of prescribed and over-the-counter medicine for pain and psychological problems among Danish adolescents—A longitudinal study. European Journal of Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-014-2294-6

*Klanšček, H., Žiberna, J., Korošec, A., Zurc, J., & Albreht, T. (2014). Mental health inequalities in Slovenian 15-year-old adolescents explained by personal social position and family socioeconomic status. International Journal for Equity in Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-26

Knoll, L. J., Magis-Weinberg, L., Speekenbrink, M., & Blakemore, S. (2015). Social influence on risk perception during adolescence. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615569578

Kraus, L., Seitz, N.-N., Piontek, D., Molinaro, S., Siciliano, V., Guttormsson, U., Arpa, S., Monshouwer, K., Leifman, H., Vicente, J., Griffiths, P., Clancy, L., Feijão, F., Florescu, S., Lambrecht, P., Nociar, A., Raitasalo, K., Spilka, S., Vyshinskiy, K., & Hibell, B. (2018). ‘Are The Times A-Changin’? Trends in adolescent substance use in Europe. Addiction, 113(7), 1317–1332.

*Kusumawardani, N., Tarigan, I., Suparmi, & Schlotheuber, A. (2018). Socio-economic, demographic and geographic correlates of cigarette smoking among Indonesian adolescents: Results from the 2013 Indonesian Basic Health Research (RISKESDAS) survey. Global Health Action, https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1467605

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press.

*Lester, L., Mander, D. J., & Cross, D. (2015). Bullying behaviour following students’ transition to a secondary boarding school context. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health, 8(2), 141–150.

Levine, M. (2006). The price of privilege: How parental pressure and material advantage are creating a generation of discontented and unhappy kids. Harper Collins Publishers.

López-Cañada, E., Devís-Devís, J., Pereira-García, S., & Pérez-Samaniego, V. (2021). Socio-ecological analysis of trans people’s participation in physical activity and sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690219887174

*Lu, S., Du, S., Hu, X., Zou, S., Liu, W., Ba, L., & Ma, G. (2015). Drinking patterns and the association between socio-demographic factors and adolescents’ alcohol use in three metropolises in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120202037

Lubman, D. I., Hides, L., Yücel, M., & Toumbourou, J. (2007). Intervening early to reduce developmentally harmful substance use amongst youth populations. Medical Journal of Australia. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01331.x

*Lund, T. J., & Dearing, E. (2012). Is Growing up affluent risky for adolescents or is the problem growing up in an affluent neighborhood? Journal of Research on Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00829.xt

*Lund, T. J., Dearing, E., & Zachrisson, H. D. (2017). Is Affluence a risk for adolescents in Norway? Journal Research on Adolescents. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12304

*Luo, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, H., & Chen, A. (2016). The influence of family socio-economic status on learning burnout in adolescents: Mediating and moderating effects. Journal of Child and Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0400-2

Luthar, S. (2003). The culture of affluence: Psychological costs of material wealth. Child Development. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00625.x

*Luthar, S. S., & Barkin, S. H. (2012). Are affluent youth truly “at risk”? Development and psychopathology vulnerability and resilience across three diverse samples. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 429–449.

*Luthar, S. S., & Kumar, N. L. (2018). Youth in high-achieving schools: Challenges to mental health and directions for evidence-based interventions. In A. W. Leschied, D. H. Saklofske, & G. L. Flett (Eds.), Handbook of School-Based Mental Health Promotion. Springer International Publishing.

Luthar, S. S., & Kumar, N. L. Z. (2020). High-achieving schools connote risks for adolescents: problems documented, processes implicated, and directions for interventions. The American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000556

Luthar, S. S., Small, P. J., & Ciciolla, L. (2018). Adolescents from upper middle class communities: Substance misuse and addiction across early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000645

*Lyman, E. L., & Luthar, S. S. (2014). Further evidence on the “Costs of Privilege”: Perfectionism in high achieving youth at socioeconomic extremes. Psychology in the Schools. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21791

*Maenhout, L., Peuters, C., Cardon, G., Compernolle, S., Crombez, G., & DeSmet, A. (2020). The association of healthy lifestyle behaviors with mental health indicators among adolescents of different family affluence in Belgium. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09102-9

*Mander, D. J., Lester, L., & Cross, D. (2015). The social and emotional well-being and mental health implications for adolescents transitioning to secondary boarding school. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health, 8(2), 131–140.

*Mazur, J., Tabak, I., Dzielska, A., Wąż, K., & Oblacińska, A. (2016). The relationship between multiple substance use, perceived academic achievements, and selected socio-demographic factors in a polish adolescent sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13121264

*Mehanovic, E., Kosir, M., Talic, S., Klanscek, H. J., & Vigna-Taglianti, F. (2020). Socio-economic differences in factors associated with alcohol use among adolescents in Slovenia: A cross-sectional study. International Journal Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01460-w

*Meier, M. H., Hill, M. L., Small, P. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2015). Associations of adolescent cannabis use with academic performance and mental health: A longitudinal study of upper middle-class youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.010

*Milas, G., Klarić, I. M., Malnar, A., Šupe-Domić, D., & Slavich, G. M. (2019). Socioeconomic status, social-cultural values, life stress, and health behaviors in a national sample of adolescents. Stress and Health. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2854

*Mohammadpoorasl, A., Nedjat, S., Fakhari, A., Yazdani, K., Foroushani, A. R., & Fotouhi, A. (2012). Substance abuse in high school students in association with socio-demographic variables in northwest of Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 41(12), 40–46.