Abstract

Cyberbullying and psychoactive substance use are two common risky behaviors among adolescents, and a growing body of documents observe associations between these two phenomena. The present systematic review aims to clarify this association, analyzing the use of both legal and illegal psychoactive substances and all cyberbullying roles. To this purpose, a systematic search on PubMed, Scopus and PsycInfo databases was conducted, focusing on adolescents aged between 10 and 20 years old. The review was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, and it includes a total of fifty original articles. The majority of them observed a positive association between cyberbullying involvement and the use of psychoactive substances, especially tobacco and alcohol. Regarding moderator factors, some studies observed the aforementioned association only among girls. Moreover, controlling for gender, delinquent friends and low parental support, this association became not significant. Nevertheless, there was a lack of information about the role of those who witnessed cyberbullying, and the included articles showed mixed results regarding illegal substance use. The findings highlighted the need for further research in order to better clarify the association between cyberbullying and substance use, and equally explore all cyberbullying roles and substance types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cyberbullying is a relatively new phenomenon that has gained increasing attention. Together with substance use, it is a common behavior, especially among adolescents. They both pose health risks and are the target of preventive measures; this is particularly relevant during a vulnerable period of life such as adolescence (Kowalski et al., 2019; ESPAD Group, 2020). Besides, it has been suggested in the literature that these two behaviors may be related, although the results are still unclear and not systematized. Using these presumptions as a starting point, this study sought to systematically review the literature on the association between substance use and cyberbullying behaviors among adolescents, focusing on different substance types and different cyberbullying roles.

Cyberbullying behaviors include any conduct performed with the purpose to inflict harm or discomfort on others, through electronic or digital media. (Tokunaga, 2010) It can be perpetrated by individuals or groups and it may include, for instance, sending hostile or aggressive messages and insulting or making fun of others. Literature identifies four distinct cyberbullying roles: cyber-victims (subjects who are cyberbullied), cyber-perpetrators (subjects who perpetrate cyberbullying), cyber-victim-perpetrators (those who are both victims and perpetrators) and bystanders (subjects who witness an episode related to cyberbullying) (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015; Lozano-Blasco et al., 2020).

Regarding prevalence, previous studies show heterogeneous results observing a lifetime prevalence range of 4.9–65.0% of cyberbullying victimization and of 1.2–44.1% of cyberbullying perpetration; the last-year range prevalence was respectively 1.0-61.1% and 3.0–39.0% (Brochado et al., 2017; Kowalski et al., 2019). In general, cyberbullying could be considered an emergent public issue. The online nature of this phenomenon makes it highly pervasive: the victim can be reached anonymously in any context of their life, and any cyber-threat can remain online and viewed by several people, thus prolonging the exposure to offense and increasing the potential harm (Tokunaga, 2010; Sorrentino et al., 2019). In fact, cyberbullying is associated with several factors related to social and psychological well-being such as a low level of self-esteem (Brewer & Kerslake, 2015; Palermiti et al., 2017), internalizing symptoms (Martínez-Monteagudo et al., 2020; Turliuc et al., 2020) and even suicidal ideation (Bai et al., 2021).

Numerous articles have pointed out an association between certain roles in cyberbullying and the use of psychoactive substances. However, the results are not entirely clear and there is a lack of systematization in order to differentiate between different roles and different types of substances. In 2021, a systematic review of the literature concerning cyber and traditional bullying perpetration and substance use was conducted (Arcadepani et al., 2021). It pointed out that both bullies and cyberbullies are more likely to be engaged in the use of psychoactive substances, both legal and illegal. However, the systematic review primarily investigated traditional bullying phenomena considering that the research strategy used key terms that did not contain the term “cyberbullying”. Moreover, it only considered the perpetrator role, disregarding the other ones. Based on this, to date there are no systematic reviews that have purposefully examined the association between the use of psychoactive substances and cyberbullying with respect to all cyberbullying roles.

The Current Study

Taking into account that cyberbullying and substance use are public health issues and there is a lack of systematization of the literature results about the relationship between them, the purpose of this study is to systematically review and analyze the original articles that investigated the potential association between being cyber-victim, or cyber-perpetrator, or cyber-victim-perpetrator, or bystander, and legal or illegal psychoactive substance use. More in detail, this systematic review considered original articles without a restriction on the studies’ year of publication and it is focused on adolescents aged between 10 and 20 years.

Methods

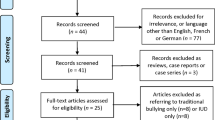

This systematic review was conducted in conformity with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) (Appendix B supplementary materials). In order to investigate the relationship between cyberbullying and psychoactive substance use, articles related to all cyberbullying roles (cyber-victim, cyber-perpetrator, cyber-victim-perpetrator, bystander) and the use of both legal and illegal psychoactive substances among adolescents were included. The protocol of this review was registered in The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (ID number: CRD42021254623) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/logout.php). The records identified and included in this qualitative synthesis showed a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of methodology, instruments used, and statistical analysis precluding a meta-analysis.

Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategy

In this qualitative synthesis, records that investigated the cyberbullying phenomenon and substance use in the population aged between 10 and 20 years were included. A systematic and online search of literature published from the database inception to the end of July 2022 was performed, using three different databases as part of the research: Scopus PsycINFO and PubMed. Database research was conducted employing the keywords and terms described in Appendix A. Given the lack of a general agreement on the cyberbullying terminology (Tokunaga, 2010), a careful search in the reference sections of the included records was also conducted, in order not to miss any possible eligible article. There wasn’t any limit for the articles ’ year of publication and the only exclusion criteria were the following: (1) subjects older than 20 years old, (2) articles in languages other than English, (3) clinical populations, (4) review or meta-analysis, (5) studies out of the scope of this qualitative synthesis (e.g., articles that considered only traditional bullying and not cyberbullying, or articles that do not directly investigate the association between substance use and cyberbullying). The search strategy was enacted by four of the authors (MB, SB, FB, and FM); two of them (MB and SB) removed duplicates and excluded irrelevant articles after screening titles and abstracts and other two authors (FB and FM) screened full-text articles assessing their eligibility, in conformity with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Mendeley Desktop was used to support the systematic search (https://www.mendeley.com/download-desktop-new/).

The articles included in the systematic review have been described in a synoptic table (see Table 1). The results are described differentiating, where possible, by type of substance and role in the cyberbullying. In particular, the synoptic table was divided into three sections. The first section describes the results for substances considered legal in the majority of the analyzed countries. The second section describes the results for substances considered illegal at any age in the majority of the analyzed countries. The third section describes the studies that did not specify or distinguish by substance type and considered them as mixed. As the legal status of many substances in almost all countries varies according to age, for each country in which the study is set, the main policies have been specified. However, it is reasonable to assume that the consumption of legal substances and the consumption of illegal substances may be different behaviors and, therefore, they are described separately.

Quality Assessment

With the aim of assessing the risk of bias in the records, two of the authors (FB and SB) independently completed the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria (SQAC) (Kmet et al., 2004) (Table 2) for each of the included records. SQAC allows for the quality assessment of both quantitative and qualitative studies in terms of research object, study design, sample size, methods, and outcomes, for a total of 14 criteria. Specifically, articles are scored by assigning one out of four different levels (no = 0, partial = 1, yes = 2, n/a = not applicable) for each assessment criterion. Inapplicable criteria were excluded from the scoring. The manual summarizing score was calculated by summing the total score reached by each article (considering only applicable criteria) and then dividing it by the total possible score (14 minus n/a x 2). The summarizing scores of the records included in this qualitative synthesis ranged from 0.64 to 1.00 (Table 2).

Results

A total of 554 records were identified from Scopus (n = 263), PsycINFO (n = 334); PubMed (n = 92) and other sources (i.e. references of the included articles) (n = 3). 349 articles were screened after removing duplicates. 166 of 349 records were excluded based on title and abstract assessment while 183 articles were evaluated for the final eligibility. 133 records were subsequently excluded on different grounds including: being a review, a meta-analysis, a study protocol, or reporting a study out of research scope. Finally, 50 articles, both cross-sectional and longitudinal observational, were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1). The included articles yielded a total sample size of 215,034 adolescents, aged between 10 and 20 years.

Of the 50 records, eleven studies investigated only legal psychoactive substances (Sourander et al., 2010; Vieno et al., 2011; Elgar et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2015; Chan & La Greca, 2016; Wiguna et al., 2018; Baiden & Tadeo, 2019; Chan et al., 2019; Rodriguez-Enriquez et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Ihongbe et al., 2021), while a total of nineteen studies investigated the association between cyberbullying and both legal and illegal psychoactive substance use (Goebert et al., 2011; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; Sampasa-Kanyinga & Hamilton, 2015; Wright, 2016; Kritsotakis et al., 2017; Carvalho et al., 2018; Graham & Wood, 2019; Lee et al., 2018; Priesman et al., 2018; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Wright & Wachs, 2019; Yoon et al., 2019; Azami & Taremian, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Carvahalo et al., 2021; Boccio et al., 2022; Nikolaou, 2022; Pichel et al., 2022). Furthermore, twenty of the included studies examined the association between cyberbullying and psychoactive substance use without differentiating substance types (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004; Mitchell et al., 2007; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Low & Espelage, 2013; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2013; Litwiller & Brausch, 2013; Reed et al., 2015; Baker & Pelfrey, 2016; Merrill & Hanson, 2016; McCuddy & Esbensen, 2017; Cénat et al., 2018; Brady et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019; Díaz & Fite, 2019; Mehari et al., 2020; Mohseny et al., 2020; Guo, 2021; Samara et al., 2021; Shawki et al., 2021; McField et al., 2022).

Psychoactive Substance Use and Cyber-victimization

Several authors found a significant link between being a cyber-victim (C-V) and using both legal and illegal psychoactive substances. Concerning alcohol use, many studies found positive associations between being a C-V and alcohol-related consumption and behaviors (Vieno et al., 2011; Goebert et al., 2011; Elgar et al., 2014; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; 2015; Chan & La Greca, 2016; Wright, 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018; Chan et al., 2019; Graham & Wood, 2019; Priesman et al., 2018; Wiguna et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Enríquez et al., 2019; Wright & Wachs, 2019; Yoon et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020; Azami & Taremian, 2020; Nikolaou, 2022, Pichel at al., 2022). In particular, concerning the behaviors linked with alcohol, findings showed a relationship between being a C-V and binge drinking (Goebert et al., 2011; Elgar et al., 2014; Chan & La Greca, 2016; Priesman et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Nikolaou, 2022), and getting drunk (Elgar et al., 2014); Zhu and colleagues (2019) observed a positive association between problematic drinking and cyberbullying victimization .Regarding cigarette consumption, several authors observed a significant association with being a C-V. Specifically, the majority of studies found a positive link between cyber-victimization and tobacco consumption (Vieno et al., 2011; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; Kritsotakis et al., 2017; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Enríquez et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Mohseny et al., 2020; Azami & Taremian, 2020 ; Nikolaou, 2022; Pichel at al., 2022), hookah, cigars, and e-cigarette use (Yoon et al., 2019), and vaping (Ihongbe et al., 2021; Boccio et al., 2022). Finally, Baiden and colleagues (2019) observed that adolescents who experienced both school bullying and cyber-victimization had higher odds of misusing prescription drugs, while Kim et al. (2019) found a positive association between being a C-V and using non-medical prescription drugs.

On the subject of illegal psychoactive substances, literature findings report a relationship between being a C-V and the use of cannabis (Goebert at al., 2011; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; 2015; Graham & Wood, 2019; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2018; Priesman et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Wright & Wachs, 2019; Yoon et al., 2019; Azami & Taremian, 2020; Nikolaou, 2022; Pichel at al., 2022), vaping marijuana among females (Boccio et al., 2022), while Wright (2016) did not detect this association. Moreover, several authors also observed a link between cyber-victimization and non-marijuana and unspecified illegal substance use (Wright, 2016; Wright & Wachs, 2019 Kritsotakis et al., 2017; Nikolaou, 2022). Conversely, Carvalho and colleagues (2018) indicated that more C-Vs reported never consuming drugs compared to non-C-Vs. Finally, many studies observed the association between cyber-victimization and psychoactive substance consumption without differentiating between substance types. Several authors found significant associations between being a C-V and consuming psychoactive substances (Mitchell et al., 2007; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Litwiller & Brausch, 2013; Reed et al., 2015; Baker & Pelfrey, 2016; Merrill & Hanson, 2016; McCuddy & Esbensen, 2017; Cénat et al., 2018; Brady et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019; Díaz & Fite, 2019; Mehari et al., 2020; Mohseny et al., 2020; Guo, 2021; Shawki et al., 2021; McField et al., 2022). Conversely, Gámez-Guadix and colleagues (2013) observed no reciprocal relationships between substance consumption and being a C-V. More specifically, results showed that the substance use (both legal and illegal) can be a predictive factor of cyber-victimization, but authors did not detect an inverse association between these two variables. Summing up, the majority of studies included in this qualitative synthesis found relationships between cyber-victimization and the use of both legal and illegal psychoactive substances, particularly alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis.

Psychoactive Substance Use and Cyber-Perpetration

Much like for cyber-victimization, literature findings pointed out significant associations between cyber-perpetration and the use of legal and illegal psychoactive substances. In particular, regarding the use of legal psychoactive substances, several authors found associations between being a cyber-perpetrator (C-P) and the use of alcohol (Sourander et al., 2010; Vieno et al., 2011; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018; Wiguna et al., 2018; Chan et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2019), getting drunk (Sourander et al., 2010), cigarettes consumption (Sourander et al., 2010; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2018), e-cig use and prescription painkillers consumption (Yoon et al., 2019). Additionally, several authors observed a significant link between cyber-perpetration and the use of cannabis (Wright & Wachs, 2019; Lee et al., 2020) and unspecified illegal psychoactive substances (Kritsotakis et al., 2017; Carvalho et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2019; Wright & Wachs, 2019; Carvalho et al., 2021).

In line with these results, when taking into considerations studies which did not differentiate between legal and illegal psychoactive substances, several authors also found significant associations between cyber-perpetration and substance use (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Low & Espelage, 2013; Mohseny et al., 2020; Guo, 2021; Shawki et al., 2021). Moreover, comparing different cyberbullying roles, Pichel and colleagues (2022) pointed out that the C-Ps had the higher rates of consumption of substances. Summing up, as for cyber-victimization, literature findings pointed out that cyber-perpetration could be associated with risky behaviors such as the use of both legal and illegal psychoactive substances.

Psychoactive Substance Use, Cyber Victimization -Perpetration And Bystanders

Some included articles also took into consideration cyber-victim-perpetrator (C-V-P) and bystander roles, showing a relationship with legal as well as illegal psychoactive substance consumption. Several authors pointed out a link between being a C-V-P and the use of alcohol (Vieno et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018; Wiguna et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2021), drunkenness (Lee et al., 2018), cigarette consumption (Vieno et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2018), cannabis use (Lee et al., 2018; 2020), and unspecified illegal drug use (Carvalho et al., 2021). Furthermore, Yoon and colleagues (2019) observed an association between the role of bystander and the use of alcohol, cigarette and e-cigarette, painkillers with medical prescription, and cannabis.

Psychoactive Substance Use, Cyberbullying and Moderator Factors

Several of the articles included in this systematic review investigated potential moderating factors of the association between cyberbullying and the use of psychoactive substances. The majority of them controlled the analyses for some variables that literature suggested to be associated with the two behaviors (e.g., household income, parental education, ethnicity, etc.). However, it is not possible to establish the specific moderate effect of each variable. Almost all included articles controlled the analyses for gender and age or school grade. Concerning gender differences, many studies considered separately male and female adolescents while the impact of age on the association between substance use and cyberbullying was not directly analyzed. Contrariwise, some authors considered parental and family factors as moderating effects (Elgar et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2018; Wright & Wachs, 2019). In particular, Elgar and colleagues (2014) showed that family dining moderated the association between C-V and the rates of psychoactive substance use. Also, Wright (2016) observed that parental social support moderates the relationship between C-V and subsequent cannabis and other illicit drug use, weakening the associations. Lee and al. (2018) pointed out that parental monitoring acts as an interaction term. When it is introduced in the analysis, the association between being a C-P and marijuana use loses its significance. Moreover, a higher parental monitoring yielded reduced the relationship of being a C-P and marijuana use. In the Carvalho and colleagues’ study (2018), the interaction term between cyberbullying and parent–child relationship made the association between C-V and smoking and binge drinking not statistically significant. Finally, Wright and Wachs (2019) found that the relationship between cyber-victimization or cyber-perpetration and non- marijuana illicit drug use was weaker at higher levels of instructive parental mediation of adolescents’ technology use.

Concerning other interpersonal variables, many studies considered friend support and peer influence (Wright, 2016; Lee and al., 2018; Gou, 2021). Wright (2016) observed that, similar to parental support, close friend social support moderates the association between C-V and nonmarijuana illicit drug use. Lee and colleagues (2018) showed that having delinquent friends enhances the association between being a C-P, cigarette use and drunkenness, and the association between being a C-V and cigarette and alcohol use. In accordance with this last point, Guo (2021) pointed out that the association between being a C-P and substance use was mediated by the delinquent peer association.

Other authors considered psychological variables. Cénat and colleagues (2018) showed a partial mediator role of psychological distress on the relationship between cyber-victimization and subsequent substance use; Rodríguez-Enríquez and colleagues (2019) pointed out that personality traits (conscientiousness, emotional instability, and extraversion) moderate the relationship between C-V and substance use, lowering the association with alcohol use and making the association with tobacco consumption not significant.

Discussion

Cyberbullying and substance use are both public health concerns. Literature suggests that there is a possible association between these two behaviors. This study aimed to systematically review the published articles on the association between cyberbullying behaviors and substance use among adolescents aged between 10 and 20 years. It is the first systematic review on this topic and it provides a comprehensive overview of the association between cyberbullying and psychoactive substance use in the adolescent population. The relationship is investigated by differentiating by type of substances and cyberbullying roles.

Cyberbullying is a phenomenon especially linked to adolescence (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008) and it increased in middle schools to high schools (Elgar et al., 2014). Literature results, collected in this review, indicate a generalized positive association between the phenomenon of cyberbullying and the use of psychoactive substances, opening the question of a possible causal relationship between the two behaviors and giving the opportunity to identify the putative moderators of the association. As mentioned in the introduction, the present study fills the literature gaps, operating at the systematization of cyberbullying and substance use results. Concerning legal substance, the majority of included studies reported an association with cyberbullying behaviors. On the topic of illegal psychoactive substance use, the most explored association was between being a cyber-victim and cannabis use (Goebert et al., 2011; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; 2015; Wright, 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Priesman et al., 2018; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Wright & Wachs, 2019; Yoon et al., 2019; Azami & Taremian, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Boccio et al., 2022) yielding mixed results.

Literature pointed out some moderating factors that can influence these associations. It emerged a significant role of parents’ behaviors (parent-offspring/child relationship and parent-monitoring) in mediating and interacting with the association between cyberbullying roles and psychoactive substance use (Lee et al., 2018; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2018; Wright & Wachs, 2019). These findings are in line with literature data on the influence of parenting on cyberbullying (Elsaesser et al., 2017). Specifically, several authors suggest that a qualitatively good relationship with parents, and the presence of parent-monitoring influence the involvement in cyber-victimization and cyber-perpetration (Elsaesser et al., 2017; Helfrich et al., 2020). Specifically, substance use could be considered a coping strategy in response to cyber-victimization (Wright, 2016; McField et al., 2022) and a good parent-offspring relationship could, in turn, influence emotional regulation as well as a coping strategy itself, favoring more adaptive ones (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2017; Cooke et al., 2019).These results pointed out the importance and the potential effectiveness of parental involvement in awareness and prevention programs related to cyberbullying and associated factors such as the use of psychoactive substances. Gender was a moderator factors of the associations between cyber-victimization and the use of legal and illegal psychoactive substances (Priesman et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Kritsotakis et al., 2017; Ihongbe et al., 2021; Boccio et al., 2022). Authors found significant association between being a cyber-victim and the use of alcohol (Priesman et al., 2018), binge drinking, smoking cigarettes, non-medical drugs consumption (Kim et al., 2019), and e-cigarettes use (Ihongbe et al., 2021) among female students only. In order to find an explanation for this result, it is important to note that girls involved in cyber-victimization may experience more relational, and reputational victimization than boys (Chan & La Greca, 2016; Priesman et al., 2018). It may result in a long-term experience of distress, which is in turn associated with substance consumption (Chan & La Greca, 2016; Priesman et al., 2018). However, other explanations could be related to being female and experiencing maladaptive behaviors such as using psychoactive substances seem to be predictor factors for cyber-victimization (Baldry et al., 2015; Guo, 2016). On the other hand, not all the included studies found gender effect interactions (Carvalho et al., 2018) leaving open the issue of a possible gender effect involved in the association between cyber-victimization and psychoactive substance use. In summary, substance use is related to cyberbullying involvement; however, this relationship is complex and influenced by important factors such as the parent-child relationship, peer influence, and gender. These results emphasize the importance of considering the multidimensionality of cyberbullying and its association with substance use in order to prevent these harmful behaviors and their consequences.

To date it is impossible to determine if there is a casual relationship between cyberbullying and substance use and both behaviors may be related to common mechanisms. For instance, they may be linked to high levels of impulsivity (López-Larrañaga & Orue, 2019; Gullo & Dawe, 2008) or sensation seeking (Evans-Polce et al., 2018; Graf et al., 2019) or to low levels of self-esteem (Donnelly et al., 2008; Palermiti et al., 2017). All these factors were positively associated with both cyberbullying and substance use. In particular, high levels of impulsivity or sensation seeking may lead to perpetuating cyberbullying. In contrast, a low level of self-esteem may be associated with being a cyber-victim and a cyber-perpetrator.

In general, literature findings are primarily focused on cyber-victims, whereas less attention is devoted to cyber-perpetrators and cyber victim-perpetrators. Only one study (Yoon et al., 2019) considers bystanders. Another aspect that should be mentioned is that the roles of cyberbullying are often associated with each other, so many adolescents involved in this phenomenon are both victims and perpetrators (Lozano-Blasco et al., 2020). It is possible to wonder whether the association of multiple roles also leads to a more significant association with the use of psychoactive substances. According to the present review, this question has not yet been fully answered: on the one hand, adolescents who had more than one role in cyberbullying were more likely to use cannabis than those who were involved in only one role (Yoon et al., 2019) and cyber victim-perpetrators use more alcohol than cyber-victim only (Carvalho et al., 2021), on the other hand it is not confirmed by the other cross-sectional studies that consider the role of the cyber victim-perpetrator and its association with cannabis use (Lee et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020) or with illegal drug use in general (Carvalho et al., 2021). Besides, considering cyberbullying roles, it emerged that some of them were very little explored (i.e. cyber victim-perpetrators and bystanders) making their association with psychoactive substances less transparent and weaker.

Regarding the legal status of substances, some consideration emerged. It is important to note that, even if some substances are legal, they are often forbidden for adolescents. These findings highlight that they are sometimes used also under the age at which they could legally consume. Moreover, given that legal psychoactive substances are more easily accessible compared to illegal ones, these data highlighted the importance of considering their relationship with cyberbullying phenomena in terms of prevention and involvement-monitoring. It is also important to note that in some countries cannabis is considered a legal substance. Among included articles, there are some studies conducted in Canada, where cannabis is legal for people older than 18 years. In line with legal substance results, they all pointed out an association between cannabis use and cyberbullying behaviors (Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2014; Sampasa-Kanyinga & Hamilton, 2015; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019). Continuing on this point, it also emerged that the legal status and policy on the substances are not uniform for all countries and it may partially be a limitation. For some adolescents included in the analyzed studies consuming certain substances (e.g. alcohol, cigarettes) may be legal. At the same time, for others, it may be forbidden with different consequences (the policies related to each substance for the considered countries are reported in the synoptic table so that readers can also compare the main finding, differentiating by policy type). Studies often do not distinguish between ages, nor consider the change in the substances’ legal status. Anyway, the results are consistent between different countries, giving strength to the findings.

Considering substance types, the literature has analyzed several different substances, but a differentiation according to the frequency or type of use has not been addressed in depth. Specifically, only one study (Pichel et al., 2022) analyzed problematic substance consumption considering alcohol and substance use in general. It showed that adolescents involved in any cyberbullying role had significantly higher rates of problematic use. Considering the increased risk to the health and well-being of adolescents associated with problematic substance use, these results are significant but need further investigations in other studies. Moreover, some types of substances need to be explored more. For instance, e-cigarettes and vaping were little analyzed, while no study considered energy drink consumption. Several studies did not distinguish between the substances investigated but instead used a unique variable comprehending more than one substance, either describing/defining it in the methods or leaving it not fully explained. This may be a further literature limitation because it is not possible to understand the specific relationship with each substance.

Even if most included study controlled for gender, age and other variables that may influence the relationship between cyberbullying and substance use, no study investigated the impact of age on this association. Furthermore, some articles considered school grade instead of age, which may be less precise, given that not all students in a particular grade have necessarily the same age. Further research may focus more on age, given that both substance use and cyberbullying behavior change when young people grow up and go through different stages of adolescence (Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; Elgar et al., 2014).

The present study also pointed out some gaps in the scientific literature. Future studies should investigate these associations further and establish possible causal relationships between the variables. Moreover, this systematic review could help spread awareness of factors impacting cyberbullying and substance use. Despite these important strengths, there are also some limitations. A possible inconsistency could have been raised by the different definitions of “cyberbullying” used in the selected articles. Some older studies could have interpreted the term and phenomenon differently than recent ones. This is also relevant for the choice of keywords in the online search. Considering that some studies were published before a more unambiguous definition of cyberbullying, the preliminary searches may have potentially missed relevant studies, defining the phenomenon through different terminology. To overcome this bias, a careful search of the bibliographies of the included studies was carried out. Older studies, which, for example, reported the term “online bullying”, were found and included in the analysis. Finally, this systematic review could have been influenced by publication bias, such as language bias, due to studies not published in English being excluded.

Conclusion

The scientific literature reports an association between cyberbullying and substance use. However, the results are often discordant and they need a systematization to better understand this topic. After systematic research on three databases, 50 original articles were included. They were conducted on adolescents aged between 10 and 20 years and written in English. Overall, psychoactive substance was generally associated with cyberbullying involvement, considering both legal and illegal substances. A certain complexity characterizes this relationship, which is influenced by the type and number of cyberbullying roles, type of substance used, gender, peer influence and parent-offspring relationship. Most studies used a cross-sectional design, so it is not easy to establish a causal link between these two behaviors. Moreover, this qualitative synthesis highlights some important literature gaps. First of all, not all cyberbullying roles were equally explored, and the same is true regarding the types of substance analyzed. Besides, there is a lack of information regarding different patterns of substance use, e.g. problematic or frequent use. Several studies, although they controlled for possible confounding factors, did not investigate the influential mediating role of the relationship of age or socio-economical, interpersonal, or psychological variables. Further research is needed to fill the gaps in the literature that have emerged through this systematic review.

References

Arcadepani, F. B., Eskenazi, D. Y., Fidalgo, T. M., & Hong, J. S. (2021). An exploration of the link between bullying perpetration and substance use: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 22(1), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019837593.

*Azami, M. S., & Taremian, F. (2020). Victimization in traditional and cyberbullying as risk factors for substance use, self-harm and suicide attempts in high school students. Scandinavian journal of child and adolescent psychiatry and psychology, 8, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.21307/sjcapp-2020-010.

Bai, Q., Huang, S., Hsueh, F. H., & Zhang, T. (2021). Cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation: a crumbled belief in a just world. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106679.

*Baiden, P., & Tadeo, S. K. (2019). Examining the association between bullying victimization and prescription drug misuse among adolescents in the United States. Journal of affective disorders, 259, 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.063.

*Baker, T., & Pelfrey, W. V. Jr. (2016). Bullying victimization, social network usage, and delinquent coping in a sample of urban youth: examining the predictions of general strain theory. Violence and victims, 31(6), 1021–1043. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00154.

Baldry, A. C., Farrington, D. P., & Sorrentino, A. (2015). “Am I at risk of cyberbullying”? A narrative review and conceptual framework for research on risk of cyberbullying and cybervictimization: the risk and needs assessment approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.014.

*Boccio, C. M., Leal, W. E., & Jackson, D. B. (2022). Bullying victimization and nicotine and Marijuana Vaping among Florida Adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 109536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109536.

*Brady, C. M., Baker, T., & Pelfrey, W. V. Jr. (2019). Comparing the impact of bullying victimization on drug use and weapon carrying among male and female middle and high school students: a partial test of general strain theory. Deviant Behavior, 41(12), 1601–1615. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1637405.

Brewer, G., & Kerslake, J. (2015). Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.073.

Brochado, S., Soares, S., & Fraga, S. (2017). A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 18(5), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016641668.

*Carvalho, M., Branquinho, C., & de Matos, M. G. (2018). Emotional symptoms and risk behaviors in adolescents: Relationships with cyberbullying and implications on well-being. Violence and victims, 33(5), 871–885. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-16-00204.

*Carvalho, M., Branquinho, C., & de Matos, M. G. (2021). Cyberbullying and bullying: impact on psychological symptoms and well-being. Child Indicators Research, 14(1), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09756-2.

*Cénat, J. M., Blais, M., Lavoie, F., Caron, P. O., & Hébert, M. (2018). Cyberbullying victimization and substance use among Quebec high schools students: the mediating role of psychological distress. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.014.

*Chan, S. F., & La Greca, A. M. (2016). Cyber victimization and aggression: are they linked with adolescent smoking and drinking?. Child & Youth Care Forum (45 vol., pp. 47–63). Springer US. 1https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9318-x.

*Chan, S. F., Greca, L., A. M., & Peugh, J. L. (2019). Cyber victimization, cyber aggression, and adolescent alcohol use: short-term prospective and reciprocal associations. Journal of adolescence, 74, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.05.003.

*Chang, F. C., Chiu, C. H., Miao, N. F., Chen, P. H., Lee, C. M., Chiang, J. T., & Pan, Y. C. (2015). The relationship between parental mediation and internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Comprehensive psychiatry, 57, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.013.

*Choi, K. S., Earl, K., Lee, J. R., & Cho, S. (2019). Diagnosis of cyber and non-physical bullying victimization: a lifestyles and routine activities theory approach to constructing effective preventative measures. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.014.

Cooke, J. E., Kochendorfer, L. B., Stuart-Parrigon, K. L., Koehn, A. J., & Kerns, K. A. (2019). Parent–child attachment and children’s experience and regulation of emotion: a meta-analytic review. Emotion, 19(6), 1103–1126. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000504.

*Díaz, K. I., & Fite, P. J. (2019). Cyber victimization and its association with substance use, anxiety, and depression symptoms among middle school youth. Child & Youth Care Forum (Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 529–544). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09493-w

Donnelly, J., Young, M., Pearson, R., Penhollow, T. M., & Hernandez, A. (2008). Area specific self-esteem, values, and adolescent substance use. Journal of Drug Education, 38(4), 389–403. https://doi.org/10.2190/DE.38.4.f.

*Elgar, F. J., Napoletano, A., Saul, G., Dirks, M. A., Craig, W., Poteat, V. P., & Koenig, B. W. (2014). Cyberbullying victimization and mental health in adolescents and the moderating role of family dinners. JAMA pediatrics, 168(11), 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1223.

Elsaesser, C., Russell, B., Ohannessian, C. M., & Patton, D. (2017). Parenting in a digital age: a review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggression and violent behavior, 35, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.06.004.

ESPAD Group (2020). ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on

Evans-Polce, R. J., Schuler, M. S., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2018). Gender-and age-varying associations of sensation seeking and substance use across young adulthood. Addictive behaviors, 84, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.003.

Gámez-Guadix, M., Gini, G., & Calvete, E. (2015). Stability of cyberbullying victimization among adolescents: prevalence and association with bully–victim status and psychosocial adjustment. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.007.

*Gámez-Guadix, M., Orue, I., Smith, P. K., & Calvete, E. (2013). Longitudinal and reciprocal relations of cyberbullying with depression, substance use, and problematic internet use among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4), 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.030.

*Goebert, D., Else, I., Matsu, C., Chung-Do, J., & Chang, J. Y. (2011). The impact of cyberbullying on substance use and mental health in a multiethnic sample. Maternal and child health journal, 15(8), 1282–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0672-x.

Graf, D., Yanagida, T., & Spiel, C. (2019). Sensation seeking’s Differential Role in Face-to-face and Cyberbullying: taking Perceived Contextual Properties into Account. Frontiers in psychology, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01572.

*Graham, R., & Wood, F. R. Jr. (2019). Associations between cyberbullying victimization and deviant health risk behaviors. The Social Science Journal, 56(2), 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.05.005.

Gullo, M. J., & Dawe, S. (2008). Impulsivity and adolescent substance use: rashly dismissed as “all-bad”? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(8), 1507–1518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.003.

Guo, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the predictors of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Psychology in the Schools, 53(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21914.

*Guo, S. (2021). Moderating effects of delinquent peer association, social control, and negative emotion on cyberbullying and delinquency: Gender differences. School psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000449

Helfrich, E. L., Doty, J. L., Su, Y. W., Yourell, J. L., & Gabrielli, J. (2020). Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377.

*Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2008). Cyberbullying: an exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant behavior, 29(2), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639620701457816.

*Ihongbe, T. O., Olayinka, P. O., & Curry, S. (2021). Association between bully victimization and vaping among Texas high school students. American journal of preventive medicine, 61(6), 910–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.06.004.

*Kim, S., Kimber, M., Boyle, M. H., & Georgiades, K. (2019). Sex differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation in adolescents. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718777397.

Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. https://www.ihe.ca/publications/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., & McCord, A. (2019). A developmental approach to cyberbullying: prevalence and protective factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.009.

*Kritsotakis, G., Papanikolaou, M., Androulakis, E., & Philalithis, A. E. (2017). Associations of bullying and cyberbullying with substance use and sexual risk taking in young adults. Journal of nursing scholarship, 49(4), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12299.

*Lee, J., Choi, M. J., Thornberg, R., & Hong, J. S. (2020). Exploring sex differences in the association between bullying involvement and Alcohol and Marijuana Use among US Adolescents in 6th to 10th Grade. Substance use & misuse, 55(8), 1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1725054.

*Lee, J., Hong, J. S., Resko, S. M., & Tripodi, S. J. (2018). Face-to-face bullying, cyberbullying, and multiple forms of substance use among school-age adolescents in the USA. School mental health, 10(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9231-6.

*Litwiller, B. J., & Brausch, A. M. (2013). Cyber bullying and physical bullying in adolescent suicide: the role of violent behavior and substance use. Journal of youth and adolescence, 42(5), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9925-5.

López-Larrañaga, M., & Orue, I. (2019). Interaction of psychopathic traits in the prediction of cyberbullying behavior. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 24(1), https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.23932.

*Low, S., & Espelage, D. (2013). Differentiating cyber bullying perpetration from non-physical bullying: commonalities across race, individual, and family predictors. Psychology of Violence, 3(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030308.

Lozano-Blasco, R., Cortes-Pascual, A., & Latorre-Martínez, P. (2020). Being a cybervictim and a cyberbully–The duality of cyberbullying: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 106444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106444

Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C., Delgado, B., Inglés, C. J., & Escortell, R. (2020). Cyberbullying and social anxiety: a latent class analysis among spanish adolescents. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(2), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020406.

*McCuddy, T., & Esbensen, F. A. (2017). After the bell and into the night: the link between delinquency and traditional, cyber-, and dual-bullying victimization. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 54(3), 409–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427816683515.

*McField, A. A., Lawrence, T. I., & Okoli, I. C. (2022). Examining the relationships between cyberbullying, relational victimization, and family support on depressive symptoms and substance use among adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13591045221110126. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221110126.

*Mehari, K. R., Thompson, E. L., & Farrell, A. D. (2020). Differential longitudinal outcomes of in-person and cyber victimization in early adolescence. Psychology of violence, 10(4), 367. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000250.

*Merrill, R. M., & Hanson, C. L. (2016). Risk and protective factors associated with being bullied on school property compared with cyberbullied. BMC public health, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2833-3.

*Mitchell, K. J., Ybarra, M., & Finkelhor, D. (2007). The relative importance of online victimization in understanding depression, delinquency, and substance use. Child maltreatment, 12(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559507305996.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

*Mohseny, M., Zamani, Z., Akhondzadeh Basti, S., Sohrabi, M. R., Najafi, A., & Tajdini, F. (2020). Exposure to Cyberbullying, Cybervictimization, and related factors among Junior High School Students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.99357.

*Nikolaou, D. (2022). Bullying, cyberbullying, and youth health behaviors. Kyklos, 75(1), 75–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12286.

Palermiti, A. L., Servidio, R., Bartolo, M. G., & Costabile, A. (2017). Cyberbullying and self-esteem: an italian study. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.026.

*Pichel, R., Feijóo, S., Isorna, M., Varela, J., & Rial, A. (2022). Analysis of the relationship between school bullying, cyberbullying, and substance use. Children and Youth Services Review, 134, 106369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106369.

*Priesman, E., Newman, R., & Ford, J. A. (2018). Bullying victimization, binge drinking, and marijuana use among adolescents: results from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 50(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2017.1371362.

*Reed, K. P., Nugent, W., & Cooper, R. L. (2015). Testing a path model of relationships between gender, age, and bullying victimization and violent behavior, substance abuse, depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 55, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.05.016.

*Rodríguez-Enríquez, M., Bennasar-Veny, M., Leiva, A., & Yañez, A. M. (2019). Alcohol and tobacco consumption, personality, and cybervictimization among adolescents. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(17), 3123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173123.

*Samara, M., Massarwi, A. A., El-Asam, A., Hammuda, S., Smith, P. K., & Morsi, H. (2021). The mediating role of bullying and victimization on the relationship between problematic internet use and substance abuse among adolescents in the UK: the parent–child relationship as a moderator. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.493385

*Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., & Hamilton, H. A. (2015). Use of social networking sites and risk of cyberbullying victimization: a population-level study of adolescents. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 18(12), 704–710. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0145.

*Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Lalande, K., & Colman, I. (2018). Cyberbullying victimization and internalising and externalising problems among adolescents: The moderating role of parent–child relationship and child’s sex. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, E8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000653.

*Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Roumeliotis, P., & Xu, H. (2014). Associations between cyberbullying and school bullying victimization and suicidal ideation, plans and attempts among canadian schoolchildren. PloS one, 9(7), e102145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102145.

*Shawki, B., Al-Hadithi, T., & Shabila, N. (2021). Association of bullying behaviour with smoking, alcohol use and drug use among school students in Erbil City, Iraq. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 27(5), https://doi.org/10.26719/2021.27.5.483.

Sorrentino, A., Baldry, A. C., Farrington, D. P., & Blaya, C. (2019). Epidemiology of cyberbullying across Europe: differences between countries and genders. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 19(2), https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2019.2.005.

*Sourander, A., Klomek, A. B., Ikonen, M., Lindroos, J., Luntamo, T., Koskelainen, M., & Helenius, H. (2010). Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: a population-based study. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(7), 720–728. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.79.

Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: a critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014.

Turliuc, M. N., Măirean, C., & Boca-Zamfir, M. (2020). The relation between cyberbullying and depressive symptoms in adolescence. The moderating role of emotion regulation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 109, 106341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106341.

*Vieno, A., Gini, G., & Santinello, M. (2011). Different forms of bullying and their association to smoking and drinking behavior in italian adolescents. Journal of school health, 81(7), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00607.x.

*Wiguna, T., Ismail, R. I., Sekartini, R., Rahardjo, N. S. W., Kaligis, F., Prabowo, A. L., & Hendarmo, R. (2018). The gender discrepancy in high-risk behaviour outcomes in adolescents who have experienced cyberbullying in Indonesia. Asian journal of psychiatry, 37, 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2018.08.021.

*Wright, M. F. (2016). Cybervictimization and substance use among adolescents: the moderation of perceived social support. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 16(1–2), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2016.1143371.

*Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2019). Does parental mediation of technology use moderate the associations between cyber aggression involvement and substance use? A three-year longitudinal study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(13), 2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132425.

*Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004). Youth engaging in online harassment: Associations with caregiver–child relationships, internet use, and personal characteristics. Journal of adolescence, 27(3), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.007.

*Yoon, Y., Lee, J. O., Cho, J., Bello, M. S., Khoddam, R., Riggs, N. R., & Leventhal, A. M. (2019). Association of cyberbullying involvement with subsequent substance use among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(5), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.05.006.

*Zhu, Y., Li, W., O’Brien, J. E., & Liu, T. (2019). Parent–child attachment moderates the associations between cyberbullying victimization and adolescents’ health/mental health problems: an exploration of cyberbullying victimization among chinese adolescents. Journal of interpersonal violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519854559.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Webb, H. J., Pepping, C. A., Swan, K., Merlo, O., Skinner, E. A., & Dunbar, M. (2017). Is parent–child attachment a correlate of children’s emotion regulation and coping? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415618276.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Consiglio Nazionale Delle Ricerche (CNR) within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB participation in the conception of the study, interpretation of the data, design and coordination and drafted the manuscript; MB conceived of the study, interpretation of the data, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript; FM participated in the design of the manuscript, interpretation of the data, language editing; FB participated in the design of the manuscript and interpretation of the data; DM critical review, commentary or revision; RP critical review, commentary or revision; SM oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution; management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Silvia Biagioni and Marina Baroni are the co-first authors.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biagioni, S., Baroni, M., Melis, F. et al. Cyberbullying Roles and the Use of Psychoactive Substances: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev 8, 423–455 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00205-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00205-z