Abstract

Dramatic changes in sleep duration, schedules, and quality put adolescents at higher risk of negative outcomes, such as poorer physical and psychosocial adjustment. While significant attention has been paid to the role of proximal contexts (e.g., family), less is known about the longitudinal interplay between exo- (e.g., neighborhood characteristics) and macro-contextual (e.g., ethnic/racial discrimination) influences and adolescents’ sleep quality. Therefore, this review aimed to summarize findings from available longitudinal research to understand the role of structural factors and experiences in the distal contexts of development in influencing sleep quality in adolescence. A total of 10 studies were included in this systematic review. The results highlighted the detrimental consequences of structural factors and experiences at the exo- and macro-systems for adolescents’ sleep duration, quality, and disturbances. Specifically, neighborhood economic deprivation, ethnic/racial minority status, community violence and victimization, and ethnic/racial discrimination were all linked to significantly lower sleep quality. Overall, this review highlighted the need for more longitudinal and multi-method studies addressing sleep quality as embedded in contexts and the reciprocal influences among the multiple layers of adolescents’ development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sleep is considered a gateway to well-being, positive adjustment, and functioning at every life stage (for a review, see Chaput et al., 2016), especially in adolescence (McGlinchey, 2015). Healthy and good quality sleep can be theorized as a multidimensional construct, composed of satisfaction with sleep, alertness during waking hours, regular sleep schedule, a proper amount of sleep duration, and ease of falling asleep and returning to sleep (Buysse, 2014). However, dramatic changes in sleep duration, schedule, and quality occur in adolescence, possibly leading to depression (for a meta-analysis, see O’Callaghan et al., 2021) and poor psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Shimizu et al., 2020) and academic performance (e.g., Liu et al., 2021). Sleep changes and patterns can be conceived as embedded in and resulting from a wide range of factors positioned in the multiple concentric ecological systems of youth’s development (El-Sheikh & Sadeh, 2015; Grandner, 2019). While significant attention has been paid to the influence of individual characteristics (e.g., pubertal changes; Foley et al., 2018) and micro-contexts (e.g., parent-child relationship; for a review, see Varma et al., 2021), how sleep is intertwined with exo- (e.g., neighborhood) and macro-contextual (e.g., culture) factors is still poorly known. This study addressed this gap by adopting an ecological (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005) and transactional (Sameroff, 2009) perspective to systematically review available findings on the longitudinal interplay between sleep changes in adolescence and exo- and macro-contextual factors.

The Outer Systems of Development: The Exo- and Macro-Contexts

The ecological (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005) and transactional (Sameroff, 2009) models conceive development as a result of continuous bidirectional influences between the person and the multiple concentric systems that surround individuals and compose their ecological environment. Therefore, development unfolds within different micro-systems that closely interact with one another (i.e., the meso-system) and are nested in and influenced by broader exo- and macro-systemic factors. Micro- and meso-systems can strongly influence youth’s development and functioning since the individual is directly in contact with social agents and experiences happening in these proximal layers. However, these contexts are themselves embedded in and influenced by broader factors positioned at the exo- and macro-systems (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007).

The exo-system is the ecological milieu of proximal contexts because it comprises the interactions and processes that might affect (or be affected by) the micro- and meso-contexts, and in turn, the developing individual. For instance, an exo-systemic feature such as the neighborhood characteristics, might shape the conditions under which the core family micro-system forms and functions and in turn, influence the developing child (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007). Taking a step further, the macro-system refers to the outermost layer that includes the culture or subcultures, belief systems, and ideologies in a given time and place (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). For instance, specific cultural norms and expectations in a given place (e.g., country) can influence individual development by framing the conditions, opportunities, and challenges faced in their micro-, meso-, and exo-contexts. Elements of the exo- and macro-systems could be differentiated into two categories: the structural features (e.g., neighborhood SES, ethnic/racial minority status) and the experiences (e.g., community violence exposure, ethnic/racial discrimination) occurring at these levels. Both might highlight a nuanced interplay between adolescents’ development and sleep quality (El-Sheikh & Sadeh, 2015).

The Role of Structural Factors

Structural factors at multiple levels reflect specific features of exo- and macro-contexts that might affect youth’s outcomes and well-being. These are usually stable and enduring features that set the specific opportunities and constraints for adolescents’ development and adjustment. At the exo-system level, neighborhood structural features are particularly relevant in the study of development as they contribute to defining the ambient (e.g., noise), built (e.g., stores, street connectivity), and social (e.g., safety, crime) environments individuals inhabit (Billings et al., 2020). On this line, a core structural feature is neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation. It encompasses the physical (e.g., vacant houses), economic (e.g., average income, number of individuals receiving public assistance), and social (e.g., unemployment rate, residential instability) hazards that might contribute to creating poor and disrupted environments (Galobardes, 2006). Previous research has highlighted that neighborhood determinants might explain a significant portion of the variance in youth’s health outcomes (Sellström & Bremberg, 2006) and have been linked to poorer academic performance, drug use, higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems, and delinquency (for reviews, see Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn 2000; van Vuuren et al., 2014).

Another key factor linked to poorer adjustment outcomes is adolescents’ ethnic/racial minority status. While race and ethnicity are inherently individual features, the status of ethnic majority or minority changes depending on the specific contexts (e.g., school, neighborhood, country) in which an individual is situated. For instance, an individual can be an ethnic majority member in one setting (e.g., in the classrooms) and an ethnic minority member in other(s) (e.g., in the neighborhood or society at large). Additionally, the majority/minority status becomes salient and relevant within the macro-system’s shifting norms, attitudes, values, and expectations (Galliher et al., 2017). That is, the macro-context includes a set of cultural stereotypes and expectations that influence how ethnic/racial minority members are perceived, the challenges they face, and the opportunities they have in a given place and moment (Juang et al., 2021; Moffitt & Syed, 2021). In turn, these factors can shape the individual and social experiences of both majority and minority youth, as well as their levels of adjustment and well-being. Extant research has highlighted that ethnic/racial minority individuals tend to display poorer physical health (e.g., Schnittker & McLeod 2005) and psychological outcomes (e.g., Alegría et al., 2015) compared to their ethnic majority peers, as a consequence of systematic social inequalities faced in their proximal and distal contexts of development.

The Role of Subjective Experiences

Adolescents’ development is influenced not only by structural characteristics but also by the subjective experiences they face and the strategies they adopt to adjust to their ecological environments. Core experiences encountered in the exo-system mostly revolve around issues of exposure to violence in the community, which includes both physical victimizations (i.e., being subjected to acts of force) and witnessing violence (i.e., seeing violent acts perpetrated against others) in the neighborhood context. These experiences have been associated with externalizing problems and aggression (e.g., Pinchevsky et al., 2014; Zimmerman & Posick, 2016), emotion dysregulation, and internalizing symptoms (Gaylord-Harden et al., 2011; Heleniak et al., 2018).

Moving toward the macro-context, beliefs, values, and ideologies positioned at this level also shape adolescents’ experiences, developmental tasks, and adjustment mechanisms. It is the case for ethnic/racial discrimination, which can be conceived as a sustained adverse experience. In line with models of stress proliferation (Pearlin et al., 2005), discrimination not only increases individuals’ stress levels directly but might also set in motion additional adverse conditions (e.g., poor social relationships, low academic functioning) or increase the salience of daily hassles. These mechanisms help understand the associations found between ethnic/racial discrimination and poorer adjustment and well-being (e.g., Bayram Özdemir & Stattin 2014; Benner, 2017), which are especially impactful in adolescence. Specifically, as cognitive, emotional, and social development unfolds from early to late adolescence and into young adulthood, youth acquire more sophisticated abilities to successfully cope with experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination (e.g., Brittian et al., 2013). Therefore, younger adolescents might not be yet equipped to face instances of ethnic/racial discrimination or negative experiences in their exo- and macro-contexts. In turn, these might have more detrimental short- and long-term consequences for their adjustment and functioning (for a meta-analysis, see Benner et al., 2018).

Associations Between Sleep and Exo- and Macro-Contextual Factors

The literature reviewed so far points to the importance of structural and experiential factors in the outer contexts (exo- and macro-systems) for adolescents’ development. Taking a step further, it is worth examining the interplay between these distal ecological contexts and youth’s sleep. Sleep is conceived as a multidimensional construct consisting of quantitative and qualitative aspects, which can be evaluated through either subjective (e.g., self-report, sleep diaries) or objective (e.g., actigraphy) assessment methods. Quantitative aspects refer to sleep duration (i.e., the number of hours slept at night). In contrast, qualitative elements refer to the configuration of different sleep parameters, such as sleep efficiency (i.e., the amount of time a person is asleep during the time spent trying to sleep) and individuals’ satisfaction with their sleep. The interplay of these aspects contributes to configuring good (e.g., proper sleep duration and high sleep efficiency) or poor sleep quality (e.g., sleep deprivation and low sleep efficiency) (Meltzer et al., 2021). Poor sleep quality could also lead to insomnia symptoms, mainly difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep at night (Blake et al., 2011). Reporting poor sleep quality represents a common problem in adolescence (Gradisar et al., 2011), with short and long-term adverse health outcomes, including obesity (Fatima et al., 2016), cognitive impairment (Short et al., 2018), and mental health problems (Hestetun et al., 2018).

Addressing the interplay between structural factors of the exo- and macro-systems and sleep quality, previous cross-sectional studies highlighted how living in neighborhoods characterized by high disruption, social fragmentation, and low socioeconomic status was associated with poorer sleep duration and quality among adolescents (Pabayo et al., 2014; Umlauf et al., 2011) and adults (for a review, see Hale et al., 2015). Moreover, sleep disparities were also found among children and adolescents depending on their status as ethnic/racial minorities (for a review, see Guglielmo et al., 2018). In most studies, White majority youth reported longer total sleep time and better sleep quality than their ethnic minority peers (e.g., Marczyk Organek et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2011).

Together with the increased attention paid to structural factors at distal levels, research has also highlighted the associations between negative experiences (e.g., exposure to violence and victimization in the community, ethnic/racial discrimination) and sleep problems (i.e., repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, and consolidation), quality, and duration. For instance, early adolescents who witnessed higher levels of community violence and those who were victimized by peers at school also reported poorer sleep quality (Lepore & Kliewer, 2013). Similarly, perceived ethnic/racial discrimination was associated with decreased sleep quality among college students (Gordon et al., 2020) and was found to explain ethnic disparities in sleep outcomes (Fuller-Rowell et al., 2017). That is, African American young adults reported higher levels of perceived discrimination, which in turn accounted for shorter sleep duration and poorer efficiency over time compared to their European American peers. These results have been explained in relation to the sleep and stress disparities model (Levy et al., 2016), according to which witnessing violence, being victimized or discriminated against are detrimental events that initiate physiological stress responses in the individual, lead to intrusive thoughts, and increase reactivity to other stressors disrupting the sleep-wake cycle and hindering sleep quality (e.g., Lepore & Kliewer 2013).

Overall, the literature examining the associations between exo- and macro-contexts and sleep during adolescence is advancing rapidly (Mayne et al., 2021), recognizing the importance of distal influences combined with proximal factors. However, most of the research has adopted cross-sectional designs and has investigated each factor or ecological context separately, thus providing a scattered picture of the influences at play. Conversely, longitudinal studies allow examining the interplay between distal factors and changes (if any) in individual functioning over time, possibly providing a more nuanced understanding of the continuous dynamic transactions of the person in contexts. Thus, longitudinal designs might provide novel insights into the bidirectional influences between exo- and macro-contextual determinants and sleep during adolescence. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of longitudinal studies (Crocetti et al., 2021; Schulz et al., 2023) are becoming increasingly common as they can provide evidence on the development and interplay of the variables of interest over time. In this vein, the current study systematically reviewed longitudinal research to provide a comprehensive understanding of the transactions between adolescents’ sleep and their distal contexts of development.

The Current Study

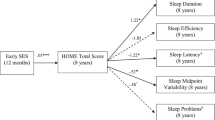

Considering the importance of proper sleep for adolescents’ adjustment and well-being, it is crucial to tackle the environmental conditions that might contribute to its developmental changes. To this end, the current study systematizes previous findings on the longitudinal associations between exo- and macro-contextual features and adolescents’ sleep. An overview of the factors examined is presented in Fig. 1. Specifically, the purpose of this systematic review is twofold. First, it aims to understand the role of structural features of the exo- (e.g., neighborhood deprivation) and macro-contextual systems (e.g., ethnic/racial minority status) in influencing youth’s sleep. Second, it examines the longitudinal interplay between the experiences in both distal contexts (e.g., community violence, ethnic/racial discrimination) and sleep. In line with the multidimensional approach to sleep, in addressing both aims, several indicators of sleep quality are considered (i.e., duration, quality, and problems). Examining sleep changes from an ecological and transactional perspective is crucial to inform evidence-based interventions aimed at supporting proper sleep during adolescence.

Method

This study was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Page et al., 2021). The PRISMA checklist is available in the Supplemental Materials (S1). This systematic review was preregistered in the PROSPERO database, registration ID: CRD42021281002. The current study is part of a larger project aiming to review longitudinal research studying the interplay between sleep quality and several socio-contextual factors (e.g., family, peers, school, and media use) in adolescence.

Eligibility Criteria

Following the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021), specific eligibility criteria were defined. Studies were eligible for the systematic review if they had the following characteristics: (a) participants had to be adolescents from the general population aged between 10/11 and 18/19 years old; (b) the study design had to be longitudinal (with at least two assessments, such as two-wave longitudinal studies or daily diaries); (c) studies examined at least one aspect of sleep and one of the exo- and macro- context (for an overview of the main dimensions see Fig. 1); (d) sleep could be measured with either objective (e.g., actigraphy, polysomnography) or subjective standardized measures (e.g., sleep diaries, questionnaires). Regarding the characteristics of the publication, both peer-reviewed journal articles and grey literature that can be retrieved through database searches (e.g., doctoral dissertations) were included to avoid selection biases and strengthen the methodological rigor of the systematic review (Ferguson & Brannick, 2012). Finally, no restrictions were applied based on the year and the language of publication.

Literature Search

To systematically identify eligible relevant research published in peer-reviewed journal articles or available as grey literature, different search strategies were applied. First, several bibliographic databases were systematically searched: Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, PubMed, MEDLINE, ERIC, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and GreyNet. In each database, the following combination of keywords was searched: (Sleep* OR insomnia* OR polysomnogram* OR REM OR actigraph* OR EEG* OR motor activity* OR circadian* OR chronotype*) AND (pediatr* OR paediatr* OR teen* OR school* OR adolescen* OR youth* OR young* OR child*) AND (longitudinal* OR prospective* OR follow up* OR daily* OR day-to-day OR wave*). Since this work was part of a larger project, the search did not include keywords specific to the exo- and macro-contexts. However, during the selection of studies, full texts were selected based on the variables examined and assigned to either this or the other systematic reviews that are part of the project. Full query strings used in each database are reported in the Supplemental Material (S2).

This main bibliographic search was complemented with additional search strategies. The websites of the journals deemed most likely to publish studies on the topic were searched. These journals were identified based on the statistics of the search previously conducted on Web of Science, selecting the fifteen journals in which most articles matching our search strategy had been published (the full list of journals is reported in the Supplemental Materials S3). This search was performed to identify in-press articles (e.g., online first) which matched the eligibility criteria. Furthermore, conference proceedings from recent sleep-related journals were screened (Journal of Sleep Research, in which European Sleep Research Society Congress proceedings were published and Sleep Medicine, in which the World Sleep Congress proceedings were published). Reference lists of the most relevant published systematic reviews and meta-analyses were also checked (e.g., Scherrer & Preckel 2021; the complete list is reported in the Supplemental Materials S4). Finally, the reference lists of included studies were checked to further identify relevant studies not initially found through the other search strategies. The first three search strategies were all performed on September 23rd, 2021, while the last one was conducted at the end of the selection process (i.e., June 2022). The searches and the screening were run and managed on Citavi 6 software.

Selection of Studies

The results of the search strategies are reported in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 2). A total of 36,748 abstracts were identified, and from these 16,327 duplicates were removed. Two raters screened the remaining records (N = 20,421) independently and simultaneously. The percentage of agreement was substantial (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.81). Discrepancies were discussed with a third rater, and the final decisions were taken reaching a consensus among the three evaluators.

A total of 371 records were selected at this step. Next, the full texts were screened following the same procedure used for abstract screening (the agreement was high; Cohen’s Kappa = 0.75). At this stage, full texts were screened and coded depending on the variable(s) examined in association with sleep. For the purpose of the current review, only studies including at least one facet of sleep and one exo- or macro-systemic outcome variable were included. In total, 10 studies were included in this systematic review (for reasons of exclusions, see Fig. 2).

Coding of Primary Studies

To extract relevant information from the selected primary studies, an excel spreadsheet was prepared. All the included studies were coded independently and simultaneously by two raters (the percentage of agreement was 91%). Discrepancies were discussed with a third rater and solved among the three evaluators.

First, the characteristics of the publication were coded: type of publication (i.e., journal article or grey literature), year of publication, and language of publication. Second, the characteristics of the studies were coded: funding sources (i.e., international funding, national funding, local funding, multiple funding sources), number of waves of the longitudinal design, interval between waves, dimensions of each study (coded according to the variables presented in Fig. 1), and source of information used to evaluate them (i.e., self-reports, objective assessment). Third, the characteristics of the participants were coded: sample size, gender composition of the sample (% females), mean age, geographical location, and ethnic composition of the sample.

Finally, data necessary for effect size computations were extracted. Due to the high heterogeneity of the studies included, different effect sizes were coded to address the first (i.e., investigating how structural factors at the exo- and macro-contexts affect sleep quality in adolescence) and the second (i.e., evaluating the interplay between exo- and macro-contextual experiences and sleep quality) aims (see Strategy of analysis section). When data for effect size computations were not reported in primary studies, study authors were contacted by email to request missing data. In total, eight authors were contacted to obtain all (or part of) the necessary data for effect size computations. If authors did not answer the first request, three reminders (one every two weeks) were scheduled. Two authors replied by providing the requested data; two replied specifying that they could not provide the required data (e.g., they could not access the dataset anymore); and four did not respond to the request. The total number of 10 studies included in the review accounts for three studies that were excluded because of insufficient data, as indicated in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 2).

Methodological Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The quality assessment of studies was performed independently by the first two authors by using an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies (Wells et al., 2022). Since the current systematic review included only longitudinal studies, the assessment areas of the scale were adapted to the relevant characteristics of the specific study design as done in previous research (e.g., Buizza et al., 2022). Specifically, the adapted version of the NOS included six items, categorized in the three dimensions of Selection, Comparability, and Outcome. For each item, a series of response options is provided, and a star system is used, assigning a maximum of one star for each Selection and Outcome items and a maximum of two stars for the Comparability item to high quality studies. The full list of items is available in Document S5 of the Supplemental Material.

Strategy of Analysis

To address the first research question (i.e., studying the role of structural factors on sleep quality), two types of effect sizes were coded. Specifically, (a) correlations were used to examine the effect of neighborhood features, and (b) sleep variables means and standard deviations of different ethnic/racial groups at each wave were extracted to estimate the mean-level differences over time based on the ethnic/racial minority status. Addressing the second research question, cross-lagged correlations were extracted to evaluate the interplay between adolescents’ sleep quality and their experiences at both the exo- (i.e., community violence exposure, victimization) and the macro- (i.e., perceived ethnic/racial discrimination) contexts. In these analyses, the sleep variables could be either dependent or independent variables, depending on how they were examined in the included studies. That is, the extracted cross-lagged correlations were based on either a specific factor measured at one time point (e.g., perceived ethnic/racial discrimination at T1) and sleep quality variables at a later time point (at T2; i.e., sleep quality as the dependent variable), or sleep quality variables at one time point (at T1; i.e., sleep quality as the independent variable) and the outcome variable measured at the following time point (e.g., perceived ethnic/racial discrimination at T2).

Due to the limited number of studies examining the variables of interest, most research questions were addressed through a qualitative review of the findings. For each study, effect sizes were estimated as Pearson’s correlations, converted into Fisher’s Z-scores for computational purposes, and converted back into correlations for presentation (Lipsey & Wilson, 2000). For ease of interpretation, correlations of |0.10|, |0.30|, and |0.50| are considered small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988; Ellis, 2010). Variance, standard error, confidence interval at 95%, and statistical significance for each effect size were computed.

When at least three studies (Cheung & Vijayakumar, 2016; Crocetti, 2016) were available, a meta-analysis was conducted using the software ProMeta3 to obtain an overall estimate. The random-effects model was used as a conservative approach to account for different sources of variation among studies (i.e., within-study variance and between-studies variance; Borenstein et al., 2010). Moreover, heterogeneity across studies was assessed with the Q statistic, to test if it was statistically significant, and the I2 index to estimate it (with values of 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively denoting a low, a moderate, and a high proportion of dispersion in the observed effects that would remain should sampling error be removed; Higgins et al., 2003). The age of participants was tested as possible moderator using meta-regression (Viechtbauer, 2007) to unravel whether the interplay between sleep and distal contexts changes at different phases of adolescence. Finally, publication bias was examined through the Egger’s regression method (Egger et al., 1997), which statistically tests the asymmetry of the funnel plot, with non-significant results indicative of the absence of publication bias.

Results

Study Characteristics

Ten studies were included in the systematic review. A summary of the characteristics of the included studies is reported in Table 1. Regarding the characteristics of the publication, most of the studies were articles published in peer-reviewed journals (90%), and only one was a dissertation. All the included studies were published in the English language. In terms of year of publication, three studies (30%) were published very recently (i.e., between 2018 and 2021) and the remaining (70%) were published before 2017. With regards to the study design, most (70%) were daily studies, and the remaining included two-time points (10%) or three or more (20%). The average time lag between adjacent waves, excluding daily studies, was almost two years and a half (M = 29.6 months, SD = 36.8 months), ranging from 5 months to 6 years. Half of the studies assessed sleep variables using self-report measures (50%), the remaining (40%) used objective measures (i.e., actigraphy), and one used both methods of assessment (10%). Most studies (70%) reported one or multiple funding sources. The total number of participants was 16,889 (M = 3,377.8, SD = 6,361.3). Most samples were gender-balanced (the average percentage of females across samples was 58.9%; range 45.7–73), and the average age of sample participants at baseline was 14.3 years (SD = 1.5, range: 11.3–15.8 years). With regards to the geographic context of the studies, all the included studies were conducted in the USA.

Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias of the Studies

Results of the methodological quality and risk of bias assessment are reported in Appendix A. Two of the authors independently evaluated the quality of the studies included with a high percentage of agreement (i.e., 90%). Specifically, nine out of the ten included studies displayed high quality and only one medium quality. Thus, the overall quality of the studies was high with a consequent low risk of bias.

The Effect of Structural Features of Exo- and Macro-Context on Sleep Variables over Time

The first aim of the current systematic review was to examine the role of structural factors in influencing adolescents’ sleep. Specifically, three studies evaluated the influence of structural elements at the exo- (i.e., neighborhood features) and macro-contexts (i.e., ethnic/racial minority status) on later levels of sleep (i.e., sleep duration, objective sleep quality, sleep disturbances). The main findings are summarized in Table 2.

One study (Bagley et al., 2018) evaluated the effect of neighborhood SES and social fragmentation on sleep duration and efficiency. It found a significant association between neighborhood features and objective measures of sleep. That is, participants living in a fragmented and indigent environment displayed shorter total sleep time, while neighborhood economic deprivation was also linked to lower levels of sleep efficiency.

Regarding the role of belonging to a minority ethnic/racial group (i.e., African American, Hispanic, biracial), three studies (Bagley et al., 2018; Bellatorre et al., 2017; El-Sheikh et al., 2016) evaluated its effect on sleep duration. Ethnic/racial minority adolescents displayed shorter sleep duration compared to their majority peers, based on both objective (i.e., actigraphy; Bagley et al., 2018; El-Sheikh et al., 2016) and subjective (i.e., self-report; Bellatorre et al., 2017) assessments. As shown in Table 3, the overall effect obtained through the meta-analytical calculation was small but significant (r = − .13, p < .05). Egger’s test was not significant, highlighting the lack of publication bias (p = .16).

Finally, only one study (Bellatorre et al., 2017) examined the association between ethnic/racial minority status and sleep disturbances. This study found a significant difference in the mean levels of insomnia symptoms between majority and minority youth, with White adolescents reporting more troubles falling asleep and more difficulties getting to sleep than Black youth, but no difference in troubles staying asleep. However, when looking at the effect size reported as Pearson’s correlation in Table 2, no significant effect of ethnic/racial minority status was found on any self-reported insomnia symptoms.

The Interplay Between Exo- and Macro-contextual Experiences and Sleep

The second aim of this review was to examine the interplay between experiences in the exo- and macro-contexts and sleep in adolescence. The selected primary studies examined a heterogeneous array of experiences, which were grouped into three main theoretical categories: community violence exposure, victimization, and ethnic/racial discrimination. The main findings are summarized in Tables 4 and 5 for experiences at the exo- and macro-contexts, respectively.

Regarding experiences at the exo-contextual level, two studies (Fairborn, 2010; Kliewer & Lepore, 2015) evaluated the longitudinal effect of community violence exposure on sleep quality in adolescence. Results showed that exposure to community violence was longitudinally associated with less subjective sleep quality and duration. Furthermore, one study (Kliewer & Lepore, 2015) found that victimization in the community was predictive of more severe sleep problems over time.

Regarding the interplay between ethnic/racial discrimination and sleep, six studies examined this link (Dunbar et al., 2017; El-Sheikh et al., 2016; Wang & Yip, 2020; Yip, 2015; Yip et al., 2020; Zeiders, 2017). Of these, four focused on the association between ethnic discrimination at one time point (T1) and sleep quality variables at a later time (at T2), which allowed for a meta-analytical calculation. As shown in Table 3, the overall effect size was significant, albeit small (r = − .07, p < .05). This result was not moderated by participants’ age at T1 (B = − 0.45, p = .66) and was not affected by publication bias, as evident from the non-significant Egger’s test (p = .87). Conversely, only two studies examined the link between sleep quality at one time point (T1) and ethnic/racial discrimination at the following time (T2). No significant effect of sleep on subsequent perceptions of ethnic/racial discrimination emerged from these studies.

Discussion

Sleep quality is embedded in and influenced by the multiple ecological contexts within which adolescents develop, from the more proximal (e.g., family, peers) to the more distal (e.g., neighborhood, culture) ones. While the former has been extensively studied, the literature has in part neglected the latter, leading to a lack of understanding of the mechanisms through which they might contribute to changes in sleep quality in adolescence. Adopting an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007), the current study addressed this gap by systematically reviewing longitudinal research focusing on the interplay between adolescents’ sleep quality and structural factors (i.e., neighborhood features, ethnic/racial minority status) and experiences (i.e., community violence exposure, victimization, and ethnic/racial discrimination) in the exo- and macro-systems of development. Overall, findings from this review highlight a nuanced pattern of associations between distal contexts and individuals’ sleep quality in adolescence. Such knowledge not only supports the notion of sleep as embedded in multiple contexts, but also highlights new directions for future research examining supportive (e.g., living in safe communities) and hindering (e.g., ethnic/racial discrimination) factors of sleep in adolescence.

Living and Being: The Role of Structural Factors on Sleep Quality

The first goal of this systematic review was to examine the associations between structural factors of the exo- (i.e., neighborhood social-economic deprivation and fragmentation) and macro-contexts (i.e., ethnic/racial minority status) and the sleep quality of adolescents. Structural factors include inherent features of the multiple contexts of development that might influence youth’s experiences and adjustment. Due to the limited number of studies examining exo-systemic structural factors, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analytical test of these links. While neighborhood social fragmentation was not associated with sleep quality, the review found a significant association between living in economically deprived neighborhoods and shorter sleep duration and poor sleep efficiency (Bagley et al., 2018). Economically disadvantaged neighborhoods might be characterized by ambient (e.g., noise, pollution) and built characteristics (e.g., connectivity, facilities) less conducive of sleep. This is in line with prior research highlighting that adolescents (e.g., Pabayo et al., 2014) and adults (e.g., Hale et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2009) living in economically disadvantaged and socially fragmented neighborhoods report more difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep. Additionally, these neighborhoods might expose individuals to pernicious social environments characterized by crime and violence. These social and environmental conditions might trigger stress responses and increased arousal, thus hindering youth’s sleep quality (Bagley et al., 2016).

Regarding the macro-systemic influences, a few more studies examined longitudinal differences in sleep quality among ethnic/racial minority and majority youth, providing a diverse pattern of results depending on the sleep measure examined. Specifically, based on results of the current meta-analysis, ethnic/racial minority status was linked to significantly shorter total sleep time. This finding highlights that minority youth are more at risk of adverse sleep and physical adjustment, in line with prior research with adolescents (for a review, see Guglielmo et al., 2018). Specifically, these differences suggest that the cultural macro-context youth are embedded in influences the experiences each individual faces depending on their status as ethnic/racial minority or majority. For instance, ethnic/racial minority members might face interpersonal (e.g., discrimination) and structural (e.g., inequality) challenges that increase the amount of stress and might in turn disrupt sleep quality. This aligns with previous studies highlighting that perceived ethnic/racial discrimination accounts for most of the ethnic/racial disparities in sleep quality (Fuller-Rowell et al., 2017). Conversely, self-reported insomnia symptoms did not significantly differ between ethnic majority and minority youth. It should be noted that none of the studies examining sleep disturbances relied on an objective assessment of these sleep variables. Future research could benefit from using a combination of subjective and objective measures to identify possible methodological (e.g., assessment used, reporting bias) and/or psychological (e.g., appraisal, coping strategies) factors explaining the ethnic/racial disparities observed and the differential effects on sleep duration and disturbances.

Overall, exo- and macro-systemic structural factors appear to exert an influence on sleep duration and efficiency of adolescents. Despite their position in distal layers, these factors are crucial determinants of the environmental conditions and experiences under which youth develop and function and consequently play a major role in skewing the quality of their sleep and general adjustment. On this line, they might activate specific physiological (e.g., arousal, heighten cortisol levels) and psychological (e.g., stress processes, worries) responses in adolescents, which reverberate on their ability to attain a high-quality sleep (Bagley et al., 2016; Watson et al., 2016). Highlighting the role of these structural factors is crucial to identify adolescents at risk and inform evidence-based interventions aimed at preventing the downward shifts in sleep quality and the negative consequences for functioning and adjustment.

Witnessing and Encountering Violence: How Experiences Influence Sleep Quality

The second aim of the current review was to tackle the longitudinal interplay between experiences at the exo- (i.e., exposure to community violence, victimization) and macro-contexts (i.e., ethnic discrimination) and the sleep quality of adolescents. Only a few studies have examined exo-systemic experiences, therefore a qualitative review of findings was conducted. Results suggest that both witnessing violence in the community and being victimized exert a negative influence on adolescents’ sleep duration, efficiency, and disturbances. This is in line with prior research (for a review, see Mayne et al., 2021) highlighting the detrimental consequences of community violence exposure on youth’s adjustment (e.g., Elsaesser et al., 2020; Heleniak et al., 2018). These experiences can be conceived as interpersonal stressors that heighten adolescents’ emotional reactivity and traumatic reactions (Heleniak et al., 2018; McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2009). These, in turn, could lead to sleep disruptions and hinder youth’s general adjustment and functioning (for a review, see Babson & Feldner 2010). Considering the scant literature on the associations between experiences of victimization and violence in the community and sleep quality, there is a need to deepen the knowledge on this interplay in adolescence. This is especially relevant because sleep might act as protective factor in preventing the detrimental effects of victimization on youth’s general adjustment, as highlighted by previous research (Hale et al., 2010; Kelly & El-Sheikh, 2014). Good sleep quality is known to strengthen individual’s cognitive and emotional abilities (Baum et al., 2014), which are fundamental resources to successfully cope with these negative experiences.

Most studies included in the current review focused on the longitudinal interplay between ethnic/racial discrimination experiences and the sleep quality of adolescents. The majority of these examined to what extent experiencing discrimination might affect subsequent sleep quality, allowing for a meta-analytical estimation of these associations. The overall effect size was significant and indicative of the detrimental consequences of ethnic/racial discrimination for sleep quality. In line with prior research with adults (Slopen et al., 2016) and young adults (Gordon et al., 2020), it could be argued that experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination heighten individual’s arousal state and activate psycho-physiological stress responses able to impair sleep functioning (Brondolo et al., 2018). Although small in size, the effect found also adds to the literature on the negative consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being (for meta-analyses, see Benner et al., 2018; Schmitt et al., 2014) and general adjustment (Benner, 2017). However, prior research has also highlighted that additional individual (e.g., acculturation strategies; Zeiders et al., 2017) and interpersonal (e.g., type of discrimination; Huynh & Gillen-O’Neel 2016) characteristics might mitigate the negative consequences of discrimination on sleep and therefore explain the small effect found in the current review.

In contrast, only few studies focused on the other direction of effects, mainly between sleep quality and subsequent ethnic/racial discrimination. The findings reviewed highlight the absence of a significant association between these factors, as poor sleep quality was not associated with increased subjective experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination. Despite that, it is worth noting that sleep patterns might play an important moderating role in the links between discrimination and adjustment. On the one hand, proper sleep might mitigate the detrimental effects of discrimination on adjustment by supporting adolescents’ adoption of effective problem solving skills (e.g., Wang & Yip, 2020) and protecting youth who are discriminated from developing depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem (e.g., Yip, 2015). On the other hand, poor sleep quality might reduce adolescents’ ability to regulate their emotions (Baum et al., 2014) and in turn intensify the perception and consequences of instances of discrimination. Considering the detrimental effects of this vicious cycle of reciprocal associations (Levy et al., 2016), more research is needed to examine the longitudinal interplay between sleep and ethnic/racial discrimination. Future studies could benefit from including multiple evaluations of sleep, perceived discrimination, and adjustment over time to unravel cross-lagged associations between the factors at play and examine mediation and moderation paths. Such studies would not only extend the knowledge on the intertwined changes in experiences, sleep quality, and functioning, but also highlight the mechanisms through which these associations develop over time.

Limitations of the Literature and Future Research Directions

The current review highlighted several limitations of the literature on the distal determinants of sleep quality in adolescence. First of all, scant research has addressed the longitudinal interplay between exo- and macro-contextual factors and experiences and sleep. More research is needed to unravel the longitudinal reciprocal associations between sleep quality and several proximal and distal factors at multiple levels. On this line, adopting a longitudinal design would be fundamental to gain a developmentally-relevant understanding of the factors contributing to changes in sleep quality at various stages of adolescence (Sadeh & El-Sheikh, 2015). Additionally, studies included in this review mostly had a specific focus, which they addressed by considering single antecedents of sleep quality. This offers a scattered picture of sleep development, while an ecological and broader perspective is needed (El-Sheikh & Sadeh, 2015). Accounting for multiple factors and experiences in the proximal (e.g., family, peer group, school) and distal (e.g., neighborhood, culture, media, policies) contexts of development would deepen the understanding of the unique and combined influences at play. Future research should also attempt to systematize these dynamics using multilevel meta-analytical strategies accounting for multiple interrelated outcomes (Moeyaert et al., 2017; Van Den Noortgate & Onghena, 2003).

A second main limitation that emerged from the current review is the lack of research adopting a combination of sleep measures. Almost all studies included used either subjective or objective methods to assess sleep duration, quality, and disturbances. Although subjective and objective sleep measures were found to be moderately to highly correlated (Meltzer et al., 2012; Werner et al., 2008), previous research with adolescents has also suggested that self-reports might overestimate sleep duration compared to actigraphic assessments (e.g., Arora et al., 2013). Therefore, future studies should strive to combine both methods, providing a reliable and more nuanced picture of antecedents and consequences of sleep quality (Sadeh, 2011).

Additionally, except for two studies (El-Sheikh et al., 2016; Wang & Yip, 2020), research included in this review has examined the unidirectional link from experiences in the distal contexts of development to subsequent sleep quality. Consequently, less is known about how sleep quality can influence perceptions of and coping with exposure to violence and victimization. Poor sleep quality can also impair adolescents’ ability to regulate their emotional reactions to the environmental and social stressors they face (e.g., Baum et al., 2014) and in turn lead to more negative consequences in terms of adjustment (Tu et al., 2015). Further research is needed to tackle these mechanisms and unravel the reciprocal longitudinal associations between sleep and experiences of violence exposure and victimization. This knowledge is crucial to identify risk and protective factors at play and inform interventions aimed at supporting adolescents’ development and adjustment.

Further, while research has examined how experiencing ethnic/racial discrimination influences sleep outcomes of ethnic minority youth, less is known about the adjustment level of members of the majority group who hold prejudicial attitudes against diverse others. On the one hand, prejudice is a known antecedent of discriminatory behaviors (Bagci & Rutland, 2019), which in turn impair ethnic minority youth’s well-being. On the other hand, endorsing ethnic prejudice has been previously linked to a set of negative outcomes (e.g., higher depression and lower self-esteem; Dinh et al., 2014; Garriott et al., 2008). Therefore, future research could also examine the interplay between ethnic prejudice levels and the sleep quality of ethnic majority adolescents. This knowledge would be fundamental to support adolescents from both the ethnic majority and minority groups in recognizing, understanding, and adjusting to the multitude of diverse cultures that characterize their worlds.

Finally, it should be noted that all studies included in the current systematic review were conducted in the USA, which is unique in terms of economic conditions (OECD, 2022), ethnic diversity (OECD, 2020), and integration policies (Solano & Huddleston, 2020). Therefore, findings from this systematic review should be generalized with caution. Cultural, political, and societal features represent additional structural factors that might influence adolescents’ functioning by directly and indirectly affecting their opportunities, experiences, and adjustment. Future studies should be conducted in other cultural contexts and with diverse populations to examine the effects of culture, society, and current and past migration patterns on youth’s development in context (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007).

Conclusion

Adopting an ecological perspective to the study of sleep and sleep changes in adolescence is crucial to gain a detailed understanding of its antecedents and consequences. However, while much attention has been paid to the proximal contexts of development, less is known about distal influences. The current study systematically reviewed longitudinal research examining the interplay between exo- and macro-contextual influences and adolescents’ sleep quality. These findings highlight the detrimental consequences of both structural factors (i.e., neighborhood economic deprivation, ethnic/racial minority status) and experiences (i.e., community violence exposure, victimization, and ethnic/racial discrimination) at the exo- and macro-system for sleep duration, quality, and problems of youth. Overall, this systematic review highlighted several gaps in the literature that future studies should fill to provide a broader understanding of sleep development in context and inform evidence-based interventions aimed at supporting this fundamental gateway for well-being and adjustment.

References

*References marked with an asterisk are included in the systematic review

Alegría, M., Green, G., McLaughlin, J., K. A., & Loder, S. (2015). Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U. S. William T. Grant Foundation.

Arora, T., Broglia, E., Pushpakumar, D., Lodhi, T., & Taheri, S. (2013). An investigation into the strength of the association and agreement levels between subjective and objective sleep duration in adolescents. PLOS ONE, 8(8), e72406. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072406.

Babson, K. A., & Feldner, M. T. (2010). Temporal relations between sleep problems and both traumatic event exposure and PTSD: a critical review of the empirical literature. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.08.002.

Bagci, S. C., & Rutland, A. (2019). Ethnic majority and minority youth in multicultural societies. In P. F. Titzmann, & P. Jugert (Eds.), Youth in superdiverse societies: growing up with globalization, diversity, and acculturation (1st ed., pp. 177–195). Routledge.

Bagley, E. J., Fuller-Rowell, T. E., Saini, E. K., Philbrook, L. E., & El-Sheikh, M. (2018). Neighborhood economic deprivation and social fragmentation: Associations with children’s sleep. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 16(6), 542–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2016.1253011.

*Bagley, E. J., Tu, K. M., Buckhalt, J. A., & El-Sheikh, M. (2016). Community violence concerns and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health, 2(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2015.12.006.

Baum, K. T., Desai, A., Field, J., Miller, L. E., Rausch, J., & Beebe, D. W. (2014). Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12125.

Bayram Özdemir, S., & Stattin, H. (2014). Why and when is ethnic harassment a risk for immigrant adolescents’ school adjustment? Understanding the processes and conditions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1252–1265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0038-y.

*Bellatorre, A., Choi, K., Lewin, D., Haynie, D., & Simons-Morton, B. (2017). Relationships between smoking and sleep problems in Black and White adolescents. Sleep, 40(1), zsw031. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw031.

Benner, A. (2017). The toll of racial/ethnic discrimination on adolescents’ adjustment. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12241.

Benner, A., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Boyle, A. E., Polk, R., & Cheng, Y. P. (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: a meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73(7), 855–883. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000204.

Billings, M. E., Hale, L., & Johnson, D. A. (2020). Physical and social environment relationship with sleep health and disorders. Chest, 157(5), 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.002.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.12.

Brittian, A. S., Toomey, R. B., Gonzales, N. A., & Dumka, L. E. (2013). Perceived discrimination, coping strategies, and mexican origin adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors: examining the moderating role of gender and cultural orientation. Applied Developmental Science, 17(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2013.748417.

Brondolo, E., Blair, I. V., & Kaur, A. (2018). Biopsychosocial mechanisms linking discrimination to health: a focus on social cognition. In B. Major, J. F. Dovidio, & B. G. Link (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of stigma, discrimination, and health (pp. 219–240). Oxford University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human. Sage Publications.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In R. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology, Theoretical Models of Human Development (5th edition, Vol. 1, pp. 793–828). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114

Buizza, C., Bazzoli, L., & Ghilardi, A. (2022). Changes in college students mental health and lifestyle during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Adolescent Research Review, 7(4), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00192-7.

Buysse, D. J. (2014). Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep, 37(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3298.

Chaput, J. P., Gray, C. E., Poitras, V. J., Carson, V., Gruber, R., Olds, T., Weiss, S. K., Gorber, C., Kho, S., M. E., & Sampson, M. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology Nutrition and Metabolism, 41(6), S266–S282. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0627.

Cheung, M. W. L., & Vijayakumar, R. (2016). A guide to conducting a meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 26(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-016-9319-z.

Cohen, J. (1988). Tha analysis of variance. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 273–406). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crocetti, E. (2016). Systematic reviews with meta-analysis: Why, when, and how? Emerging Adulthood, 4(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815617076.

Crocetti, E., Albarello, F., Prati, F., & Rubini, M. (2021). Development of prejudice against immigrants and ethnic minorities in adolescence: A systematic review with meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Developmental Review, 60, 100959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100959.

Dinh, K. T., Holmberg, M. D., Ho, I. K., & Haynes, M. C. (2014). The relationship of prejudicial attitudes to psychological, social, and physical well-being within a sample of college students in the United States. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 21(2), 56–66.

*Dunbar, M., Mirpuri, S., & Yip, T. (2017). Ethnic/racial discrimination moderates the effect of sleep quality on school engagement across high school. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(4), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000146.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Ellis, P. D. (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge university press.

Elsaesser, C., Gorman-Smith, D., Henry, D., & Schoeny, M. (2020). The longitudinal relation between community violence exposure and academic engagement during adolescence: Exploring families’ protective role. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(17–18), 3264–3285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517708404.

El-Sheikh, M., & Sadeh, A. (2015). I. Sleep and development: Introduction to the monograph. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 80(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12141.

*El-Sheikh, M., Tu, K. M., Saini, E. K., Fuller-Rowell, T. E., & Buckhalt, J. A. (2016). Perceived discrimination and youths’ adjustment: Sleep as a moderator. Journal of Sleep Research, 25(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12333.

*Fairborn, S. (2010). The effects of community violence exposure on adolescents’ health. University of California Riverside.

Fatima, Y., Doi, S. A., & Mamun, A. A. (2016). Sleep quality and obesity in young subjects: A meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 17(11), 1154–1166. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12444.

Ferguson, C. J., & Brannick, M. T. (2012). Publication bias in psychological science: prevalence, methods for identifying and controlling, and implications for the use of meta-analyses. Psychological Methods, 17(1), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024445.

Foley, J. E., Ram, N., Susman, E. J., & Weinraub, M. (2018). Changes to sleep-wake behaviors are associated with trajectories of pubertal timing and tempo of secondary sex characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 68, 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.017.

Fuller-Rowell, T. E., Curtis, D. S., El-Sheikh, M., Duke, A. M., Ryff, C. D., & Zgierska, A. E. (2017). Racial discrimination mediates race differences in sleep problems: a longitudinal analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000104.

Galliher, R. V., McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. (2017). An integrated developmental model for studying identity content in context. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2011–2022. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000299.

Galobardes, B. (2006). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.023531.

Garriott, P. O., Love, K. M., & Tyler, K. M. (2008). Anti-black racism, self-esteem, and the adjustment of White students in higher education. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/1938-8926.1.1.45.

Gaylord-Harden, N., Cunningham, J., & Zelencik, B. (2011). Effects of exposure to community violence on internalizing symptoms: Does desensitization to violence occur in African American youth? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 711–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9510-x.

Gordon, A. M., Prather, A. A., Dover, T., Espino-Pérez, K., Small, P., & Major, B. (2020). Anticipated and experienced ethnic/racial discrimination and sleep: a longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(12), 1724–1735. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220928859.

Gradisar, M., Gardner, G., & Dohnt, H. (2011). Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: A review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Medicine, 12(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.008.

Grandner, M. A. (2019). Social-ecological model of sleep health. Sleep and health (pp. 45–53). Elsevier.

Guglielmo, D., Gazmararian, J. A., Chung, J., Rogers, A. E., & Hale, L. (2018). Racial/ethnic sleep disparities in US school-aged children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Sleep Health, 4(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2017.09.005.

Hale, L., Emanuele, E., & James, S. (2015). Recent updates in the social and environmental determinants of sleep health. Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 1(4), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-015-0023-y.

Hale, L., Hill, T. D., & Burdette, A. M. (2010). Does sleep quality mediate the association between neighborhood disorder and self-rated physical health? Preventive Medicine, 51(3), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.017.

Heleniak, C., King, K. M., Monahan, K. C., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2018). Disruptions in emotion regulation as a mechanism linking community violence exposure to adolescent internalizing problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(1), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12328.

Hestetun, I., Svendsen, M. V., & Oellingrath, I. M. (2018). Sleep problems and mental health among young norwegian adolescents. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 72(8), 578–585.

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Hill, T. D., Burdette, A. M., & Hale, L. (2009). Neighborhood disorder, sleep quality, and psychological distress: Testing a model of structural amplification. Health & Place, 15(4), 1006–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.04.001.

Huynh, V. W., & Gillen-O’Neel, C. (2016). Discrimination and sleep: The protective role of school belonging. Youth & Society, 48(5), 649–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X13506720.

Juang, L. P., Moffitt, U., Schachner, M. K., & Pevec, S. (2021). Understanding ethnic-racial identity in a context where “race” is taboo. Identity, 21(3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2021.1932901.

Kelly, R. J., & El-Sheikh, M. (2014). Reciprocal relations between children’s sleep and their adjustment over time. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1137–1147. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034501.

*Kliewer, W., & Lepore, S. J. (2015). Exposure to violence, social cognitive processing, and sleep problems in urban adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0184-x.

Lepore, S. J., & Kliewer, W. (2013). Violence exposure, sleep disturbance, and poor academic performance in middle school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1179–1189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9709-0.

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309.

Levy, D. J., Heissel, J. A., Richeson, J. A., & Adam, E. K. (2016). Psychological and biological responses to race-based social stress as pathways to disparities in educational outcomes. American Psychologist, 71(6), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040322.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2000). Practical meta-analysis (49 vol.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Liu, X., Zhang, L., Wu, G., Yang, R., & Liang, Y. (2021). The longitudinal relationship between sleep problems and school burnout in adolescents: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 88, 14–24.

Marczyk Organek, K. D., Taylor, D. J., Petrie, T., Martin, S., Greenleaf, C., Dietch, J. R., & Ruiz, J. M. (2015). Adolescent sleep disparities: Sex and racial/ethnic differences. Sleep Health, 1(1), 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.003.

Mayne, S. L., Mitchell, J. A., Virudachalam, S., Fiks, A. G., & Williamson, A. A. (2021). Neighborhood environments and sleep among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 57, 101465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101465.

McGlinchey, E. L. (2015). Sleep and adolescents. In Sleep and Affect (pp. 421–439). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-417188-6.00019-0

McLaughlin, K. A., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.019.

Meltzer, L. J., Montgomery-Downs, H. E., Insana, S. P., & Walsh, C. M. (2012). Use of actigraphy for assessment in pediatric sleep research. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16(5), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2011.10.002.

Meltzer, L. J., Williamson, A. A., & Mindell, J. A. (2021). Pediatric sleep health: It matters, and so does how we define it. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 57, 101425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101425.

Moeyaert, M., Ugille, M., Natasha Beretvas, S., Ferron, J., Bunuan, R., & Van den Noortgate, W. (2017). Methods for dealing with multiple outcomes in meta-analysis: A comparison between averaging effect sizes, robust variance estimation and multilevel meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1252189.

Moffitt, U., & Syed, M. (2021). Ethnic-racial identity in action: structure and content of friends’ conversations about ethnicity and race. Identity, 21(1), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2020.1838804.

Moore, M., Kirchner, H. L., Drotar, D., Johnson, N., Rosen, C., & Redline, S. (2011). Correlates of adolescent sleep time and variability in sleep time: The role of individual and health related characteristics. Sleep Medicine, 12(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.07.020.

O’Callaghan, V. S., Couvy-Duchesne, B., Strike, L. T., McMahon, K. L., Byrne, E. M., & Wright, M. J. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relationship between subjective sleep and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Sleep Medicine, 79, 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.01.011.

OECD (2020). International Migration Outlook 2020. https://doi.org/10.1787/ec98f531-en

OECD (2022). OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2022. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/eeb7cbe9-en

Pabayo, R., Molnar, B. E., Street, N., & Kawachi, I. (2014). The relationship between social fragmentation and sleep among adolescents living in Boston, Massachusetts. Journal of Public Health, 36(4), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu001.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003.

Pearlin, L. I., Schieman, S., Fazio, E. M., & Meersman, S. C. (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650504600206.

Pinchevsky, G. M., Fagan, A. A., & Wright, E. M. (2014). Victimization experiences and adolescent substance use: does the type and degree of victimization matter? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(2), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505150.

Sadeh, A. (2011). The role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: an update. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15(4), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2010.10.001.

Sadeh, A., & El-Sheikh, M. (2015). Sleep and development: conclusions and future directions. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 80(1), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12151.

Sameroff, A. J. (2009). The transactional model. The transactional model of development: how children and contexts shape each other (pp. 3–21). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11877-001.

Scherrer, V., & Preckel, F. (2021). Circadian preference and academic achievement in school-aged students: A systematic review and a longitudinal investigation of reciprocal relations. Chronobiology International, 38(8), 1195–1214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2021.1921788.

Schmitt, M., Branscombe, N., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035754

Schnittker, J., & McLeod, J. D. (2005). The social psychology of health disparities. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 75–103.

Schulz, S., Nelemans, S., Hadiwijaya, H., Klimstra, T., Crocetti, E., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2023). The future is present in the past: A meta-analysis on the longitudinal associations of parent–adolescent relationships with peer and romantic relationships. Child Development, 94, 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13849.

Sellström, E., & Bremberg, S. (2006). The significance of neighbourhood context to child and adolescent health and well-being: A systematic review of multilevel studies. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 34(5), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940600551251.

Shimizu, M., Gillis, B. T., Buckhalt, J. A., & El-Sheikh, M. (2020). Linear and nonlinear associations between sleep and adjustment in adolescence. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 18(5), 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2019.1665049.

Short, M. A., Blunden, S., Rigney, G., Matricciani, L., Coussens, S., Reynolds, C. M., & Galland, B. (2018). Cognition and objectively measured sleep duration in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Health, 4(3), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.004.

Slopen, N., Lewis, T. T., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Discrimination and sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine, 18, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.012.

Solano, G., & Huddleston, T. (2020). Migrant integration policy index 2020. CIDOB; Migration Policy Group. https://www.mipex.eu.

Tu, K. M., Erath, S. A., & El-Sheikh, M. (2015). Peer victimization and adolescent adjustment: The moderating role of sleep. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(8), 1447–1457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0035-6.

Umlauf, M. G., Bolland, J. M., & Lian, B. E. (2011). Sleep disturbance and risk behaviors among inner-city African-American adolescents. Journal of Urban Health, 88(6), 1130–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9591-4.

Van Den Noortgate, W., & Onghena, P. (2003). Multilevel meta-analysis: A comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(5), 765–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403251027.

van Vuuren, C. L., Reijneveld, S. A., van der Wal, M. F., & Verhoeff, A. P. (2014). Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation characteristics in child (0–18 years) health studies: A review. Health & Place, 29, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.05.010.

Varma, P., Conduit, R., Junge, M., Lee, V. V., & Jackson, M. L. (2021). A systematic review of sleep associations in parents and children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(9), 2276–2288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02002-5.

Viechtbauer, W. (2007). Accounting for heterogeneity via random-effects models and moderator analyses in meta-analysis. Journal of Psychology, 215(2), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409.215.2.104.

*Wang, Y., & Yip, T. (2020). Sleep facilitates coping: Moderated mediation of daily sleep, ethnic/racial discrimination, stress responses, and adolescent well-being. Child Development, 91(4), e833–e852. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13324.

Watson, N. F., Horn, E., Duncan, G. E., Buchwald, D., Vitiello, M. V., & Turkheimer, E. (2016). Sleep duration and area-level deprivation in twins. Sleep, 39(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5320.

Wells, G. A., Shea, C., O’Connell, D., Robertson, J., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2022, December). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Werner, H., Molinari, L., Guyer, C., & Jenni, O. G. (2008). Agreement rates between actigraphy, diary, and questionnaire for children’s sleep patterns. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(4), 350. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.4.350.

*Yip, T. (2015). The effects of ethnic/racial discrimination and sleep quality on depressive symptoms and self-esteem trajectories among diverse adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0123-x.

*Yip, T., Cham, H., Wang, Y., & El-Sheikh, M. (2020). Discrimination and sleep mediate ethnic/racial identity and adolescent adjustment: Uncovering change processes with slope‐as‐mediator mediation. Child Development, 91(3), 1021–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13276.

*Zeiders, K. H. (2017). Discrimination, daily stress, sleep, and Mexican-origin adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(4), 570–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000159.

Zeiders, K. H., Updegraff, K. A., Kuo, S. I. C., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & McHale, S. M. (2017). Perceived discrimination and Mexican-origin young adults’ sleep duration and variability: The moderating role of cultural orientations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(8), 1851–1861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0544-9.

Zimmerman, G. M., & Posick, C. (2016). Risk factors for and behavioral consequences of direct versus indirect exposure to violence. American Journal of Public Health, 106(1), 178–188. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302920.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Liesbeth Carpentier, Francesca De Lise, Francesca Golfieri, Savaş Karataş, Fabio Maratia, and Maria Pagano who helped in the selection of the studies for this systematic review.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ERC-CoG IDENTITIES Grant agreement N. [101002163]; Principal investigator: Elisabetta Crocetti).

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B. conceived the study, coded the papers included in the review, wrote the manuscript, and participated in the interpretation of the results; V.B. conceived the study, coded the papers included in the review, performed the statistical analyses, wrote the manuscript, and participated in the interpretation of the results; E.C. conceived the study, wrote the manuscript, and participated in the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

No ethical approval was needed because data from previously published studies in which informed consent was obtained by primary investigators were retrieved and analyzed.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Quality and risk of bias assessment

Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | Quality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | |||

Bagley et al., 2018 | * | * | ** | * | * | 6 | High | |

Bellatorre et al., 2017 | * | * | ** | * | * | 6 | High | |

Dunbar et al., 2017 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | High |

El Sheikh et al., 2016 | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | High | |

Fairborn, 2010 | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | High | |

Kliewer & Lepore, 2015 | * | * | ** | * | * | 6 | High | |

Wang & Yip, 2020 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | High |

Yip, 2015 | * | * | * | * | 4 | Medium | ||

Yip et al., 2020 | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 7 | High |

Zeiders, 2017 | * | * | ** | * | * | 6 | High | |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bobba, B., Bacaro, V. & Crocetti, E. Embedded in Contexts: A Systematic Review of the Longitudinal Associations Between Contextual Factors and Sleep. Adolescent Res Rev 8, 403–422 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00204-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-023-00204-0