Abstract

Adolescents in aftercare services who are transitioning from out-of-home care, also called care leavers, face more challenges in their lives, and engage in more risk behaviors, than their peers. However, no previous reviews have comprehensively addressed this issue to identify future research needs. The aim of this systematic review was to gather, assess, and synthesize previous studies concerning care leavers’ high-risk behavior. The search was conducted in six databases, with sixteen articles included in the final review. The selected research highlighted five forms of high-risk behavior: substance abuse, delinquency, sexual behavior, irresponsible use of money, and self-destructive behavior. The incidence of high-risk behavior among care leavers varied noticeably between the studies. Some of the studies reported significant connections between high-risk behavior and gender, race, reason(s) for placement, and the form and number of placements. The synthesized findings revealed a fragmented, limited view of care leavers’ high-risk behavior that highlighted substance abuse and delinquency. The development of adolescents, particularly care leavers, includes multiple factors that have either a conducive or protecting effect for high-risk behavior. Comprehensive research regarding care leavers’ high-risk behavior, including the associated factors, is needed to better support healthy development and success in transitioning to independent living.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Out-of-home care is the temporary, medium-, or long-term placement of a child or adolescent who is unable to live with their own family (Mendes & Snow, 2016). It has been estimated that approximately 2.7 million children and adolescents between the ages of 0 and 17 are living in out-of-home care across 140 countries around the world (Petrowski et al., 2017). The number of children and adolescents in out-of-home care, as well as the services they are provided, vary across countries based on cultural, political, and legislative aspects (Mendes & Snow, 2016). These young people represent a vulnerable group, and struggle with many aspects of life. In addition, they are more prone to risk behaviors than other adolescents their age (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2018; Shaw, 2017; Sims-Schouten & Hayden, 2017). Adolescence is a period of growth and development that is characterized by heightened risk-taking (Willoughby et al., 2021); these actions are defined as high-risk behavior when they increase the risk of disease or injury, disability, death, or social problems (Tariq & Gupta, 2022). The high-risk behaviors of adolescents can involve alcohol and substance abuse, use of nicotine products, reckless sexual behavior or use of money, functional addictions, eating disorders, excessive or insufficient exercise, self-destructive behavior, and delinquent behavior (e.g., Tariq & Gupta, 2022; Willoughby et al., 2021). This study focuses on the high-risk behaviors of adolescents who are transitioning from out-of-home care and/or are in aftercare services. In this article, this group of adolescents is referred to as care leavers.

Transitioning from out-of-home care to independent adult life is a complex process in which aftercare services have been found to improve adolescents’ prospects (Glynn & Mayock, 2019; Tyler et al., 2017). The knowledge base concerning the prevention of risk behaviors among children and adolescents who have been in out-of-home care relies on singular studies of substance abuse, criminality, and suicidal behavior (Havlicek et al., 2013; Gypen et al., 2017; Kääriälä & Hiilamo, 2017). As such, no previously published overview of the topic – which could guide future research – currently exists.

High-risk behavior leads to further problems and impairs the health and well-being of the individual and those who they interact with (Willoughby et al., 2021). For example, substance abuse and intoxication increase the risk of accidents, worsen behavioral disorders, and involve potentially fatal consequences (Lee et al., 2020; Kedia et al., 2021; Quimby et al., 2022). Moreover, risky sexual behavior increases the risk of exploitation, exposure to sexually transmitted diseases, and unwanted pregnancies (Hahn et al., 2021). Gaming addictions, gambling, and functional addictions can exclude adolescents from social relationships, enhance financial problems, make it difficult to engage in daily activities, and exacerbate mental health problems (Butler et al., 2020; Shoshani et al.,2021; Khalil et al., 2022). Longitudinal studies have shown that high-risk behaviors stemming from untreated behavioral disorders among adolescents lead to lower educational levels, financial difficulties, increased incidence of mental health and substance abuse problems, and higher premature mortality (Akasaki et al., 2019; Campbell et al., 2020).

The high-risk behavior of children and adolescents who have been in out-of-home care may impair the transition to independent life because these individuals already suffer from more health and well-being problems than their peers. For example, over 60% of adolescents in out-of-home care were diagnosed with a psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorder, most commonly depression and anxiety disorders, and oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder (Kääriälä et al., 2021). The transition to independent life of a care leaver who has engaged in high-risk behavior is also impaired by a lack of informal and formal support, which increases the risk of social exclusion, problems with social interaction, homelessness, unemployment, low educational levels, and financial difficulties (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2018; Nho et al., 2017). The intensity of the challenges that care leavers face has been connected to the number and form of placements, as well as the reason for the placement (Scannapieco et al., 2016).

Several factors have been shown to be associated with high-risk behaviors (e.g., Meeus et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2021; Tinner et al., 2021); these include behavioral, activity, and attention disorders, along with antisocial behavior (Song et al., 2021; Sultan et al., 2021). The underlying causes of behavioral disorders are complex; however, childhood abuse and neglect are important factors in the development of these disorders (García et al., 2021; Kobulsky et al., 2022). Untreated or medically neglected behavioral disorders can adversely affect the development of a child, as well as the transition period of adolescence (Okumura et al., 2021). The symptoms of untreated disorders usually become more visible at the start of puberty, and thus, may have serious consequences. This can result in adolescents suddenly showing significant behavioral changes, which may take an aggressive form, and manifest as high-risk behaviors, aggression, violence, and even committing crimes (Henriksen et al., 2021; Lindblad et al., 2020). A comprehensive view of the factors associated with high-risk behavior is crucial for understanding the developmental paths of adolescents and how they influence high-risk behavior. In addition, this knowledge would provide insight into the challenges which adolescents face and help identify effective ways to support vulnerable populations during and after out-of-home care.

Current Study

Knowledge of forms, prevalence and factors associated with the care leavers high-risk behavior is fragmented due to the lack of systematic review of previous empirical studies. The aim of this systematic review was to gather, assess, and synthesize previous evidence on adolescents’ high-risk behavior while in aftercare services or transitioning from out-of-home care. The research is guided by two research questions, the first of which is what kind of high-risk behaviors have been identified in previous studies of adolescents in aftercare and/or transitioning from out-of-home care? The second research question is which associations between background factors and high-risk behavior have been identified among adolescents in aftercare services and/or transitioning from out-of-home care?

Methods

Design

A systematic review was conducted based on the procedure from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021) for the identification, assessment, and synthesis of quantitative research.

Search Methods

The research team created a search strategy and search terms based on the research questions. An information specialist was consulted during the process to ensure that the terms would cover potentially relevant articles. A systematic literature search was conducted on the first of December 2021 using six databases: CINAHL; PsycInfo; PubMed; Scopus; SocIndex; and Web of Science. The same search terms were used across all six databases, except for PubMed, which also uses MeSH terms (Table 1). As PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science provided large numbers of hits, “article” was applied as a search limitation. In addition, title, abstract, and keyword were used to limit the hits in Scopus. Studies that were peer-reviewed and published between 2011 and 2021 were included in this review; no language restrictions were applied.

Search Outcome

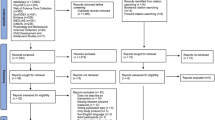

The search yielded a total of 1365 studies. These were transferred to Covidence systematic review manager, after which duplicates (n = 222) were removed by the system. Following duplicate removal, two authors (UKP, SK) independently screened the titles and abstracts (n = 1143) of relevant articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). In the next step, full-text assessment, 57 out of 124 studies were found to meet the inclusion criteria. The studies represented quantitative (cross-sectional, registry and longitudinal studies), qualitative and mixed-methods research. The content of the studies could be divided into two groups: adolescents who were in aftercare or transitioning from out-of-home care to adulthood; and adolescents with a history of out-of-home care. Due to the large number of identified articles, a decision was made to only include the studies in which adolescents were in aftercare services or transitioning from out-of-home care at the time of the research. Hence, a total of 16 studies were included in this review. The studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria will be reported in another review. Any discrepancies about the selections of studies were discussed between the two authors. If a mutually satisfactory solution was not reached, another member of the research team was asked to resolve the issue. The study identification and selection process are shown as a PRISMA flow chart in Fig. 1.

Quality Appraisal

The quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two authors (UKP, SK) using Centre for Evidence-Based Management (2014) critical appraisal of a cohort or panel study (Table 2) and critical appraisal of a cross-sectional study (survey) tools (Table 3). Both tools consisted of 12 questions, with the researcher choosing one of three options (“yes”, “can’t tell” and “no”). The two authors compared their evaluations and made a final decision based on their respective answers. No disagreements emerged at this point. The checklist did not include any guidance about rating the studies; therefore, only consistency in the quality of the studies was considered. Concerning the cohort or panel studies, eight studies scored ten or more points and two studies scored seven or more points. For the cross-sectional studies, three studies scored seven or more points and three studies scored five or more points. All of the studies that were included in the review presented a clearly worded research question, used appropriate research methods, and the sample was representative of a defined population. However, five cohort studies did not apply a validated measurement tool, and confidence intervals were not specified. Furthermore, four of the cohort studies did not adequately address possible confounding factors. The sample size in all six of the cross-sectional studies was not based on prior considerations of statistical power, and confidence intervals were not given. In five cross-sectional studies it was impossible to determine whether a satisfactory response was achieved, and four studies did not adequately address confounding factors. None of the studies were excluded following the quality assessment.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from each study and summarized in table form (Table 4). The extracted data included information such as origin of data, author(s), year of publication, study country, study aim, sample, study design and data collection, data analysis methods, and main results.

Synthesis

The data presented in the original studies were synthesized following the guidelines of the quantitative synthesis of a systematic review (McKenzie et al., 2022). At the beginning of the synthesis, the studies were read through several times, during which organized notes were made. After these notes were read through several times, data that were related to the research questions were identified from each study. Data related to the research questions were collected and aggregated based on the type and prevalence of high-risk behavior (Table 5).

Results

Characteristics of the Studies

The studies (N = 16) were conducted in five countries: Canada (n = 1); China (n = 1); Finland (n = 3); South Africa (n = 1); and the United States (n = 10). The studies employed cross-sectional and cohort designs, with some included longitudinal follow-up surveys and structured interviews. This review also includes one mixed methods study, but only the quantitative data were synthesized. Several of the included studies utilized the same data source, i.e., the 16 original articles report data from seven different sources. The studies described a total of five manifestations of high-risk behavior, namely, substance abuse (n = 14), delinquency (n = 12), sexual behavior (n = 3), irresponsible use of money (n = 1), and self-destructive behavior (n = 1). The number of participants per study ranged from 51 to 7449 and included adolescents in aftercare services and/or adolescents who were transitioning from out-of-home care (Table 4).

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse was the most common form of high-risk behavior described in the included studies, with most of the adolescents who exhibited this type of behavior abusing alcohol and drugs (Table 5). Substance abuse among adolescents ranged from around 5% (Liu et al., 2020) to almost 35% (Brown et al., 2015). Most of the studies did not specify percentages of substance abuse for different illicit substances. Among adolescents in aftercare, 45% smoked, 8% used snuff, 67% abused alcohol, 34% used drugs, 28% smoked cannabis, and 9% reported abusing medications (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2020). Longitudinal studies in which adolescents became independent and transitioned from out-of-home care at different times showed a significant reduction in substance abuse over this time period (e.g., Brown et al., 2015).

Statistically significant connections were found between substance abuse and gender, number of placements, placement type, and reason for placement (Table 6). Substance abuse was generally more common among men than women (Cusick et al., 2012; Häggman-Laitila et al., 2020; Prince et al., 2019; Toivonen et al., 2020), except in the study by Mitchell et al. (2015), i.e., substance abuse was more common among females than males. Diagnosed substance addiction or substance abuse was more common among adolescents who had been placed in out-of-home care three times or more than among adolescents who had been placed in out-of-home care once or twice (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2020; Toivonen et al., 2020). Shpiegel et al. (2020) divided the study population into different types of foster care to investigate substance abuse prevalence; accordingly, 17% of adolescents in relative foster care, 42.4% of adolescents in nonrelative foster care, 27.3% of adolescents in a group home or institution, and 13.6% of adolescents in other settings were found to demonstrate substance abuse (Shpiegel et al., 2020).

Moreover, Prince et al. (2019) found that both adolescents whose last placement had been in a group home or institutional setting and adolescents who had run away demonstrated elevated odds of substance abuse when compared to adolescents whose last placement had been non-relative foster home. Also, removal from home because of a child’s behavioral or emotional problems elevated the odds of substance abuse.

Delinquency

Delinquency was the second most commonly reported form of high-risk behavior in the included studies (Table 5). In three studies, delinquency was divided based on manifestation and severity (Cusick et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2020; van Breda, 2020). Adolescents who had been placed in out-of-home care are at a 2.5 times greater risk of incarcerated relative to adolescents who have not been in out-of-home care (Yang et al., 2017); furthermore, each additional placement increases the risk for arrest by 4% (Cusick et al., 2012). The prevalence of delinquent behavior ranged from approximately 2% (Liu et al., 2020) to almost 45% (Cusick et al., 2012). Most of the included studies reported that almost one-quarter of care leavers had committed crimes or were incarcerated (Cusick et al., 2012; Kelly, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2015; Prince et al., 2019; Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2018; van Breda, 2020).

Statistically significant connections between delinquency and background factors (gender, race, number of placements, placement form, and other factors) were found (Table 6). For example, male gender increased the risk for arrest by 100% (Cusick et al., 2012); however, Mitchell et al. (2015) reported that the records show that half of the convicted adolescents were male, and the other half were female. Being African American, compared to being White, increased the risk for arrest by 95% (Cusick et al., 2012), and similar associations were reported by Mitchell et al. (2015) and Shpiegel et al. (2020). Placement in a group home or institutional setting – relative to other care settings – increased the odds of delinquency (Cusick et al., 2012; Prince et al., 2019), while running away (Prince et al., 2019), not having a biological mother (Cusick et al., 2012), and childbirth (Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2018) were also linked with an increased risk for crime. Zinn et al. (2017) reported that delinquency and attachment insecurity are negatively associated with social support.

Other Forms of High-risk Behavior

Adolescents’ sexual health was described in three studies. Of these, two studies reported that 10% of the adolescents had a sexually transmitted disease (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2020; Toivonen et al., 2020). Problems related to sexually transmitted diseases, as well as sexual health and behavior, were more common among women than men (Table 6). Adolescents who had been placed in out-of-home care three or more times were more likely to have sexually transmitted diseases than adolescents who had been in out-of-home care fewer than three times (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2020). Lack of sexual knowledge and risky sexual behavior were reported by 20.8% of the adolescents transitioning of out-of-home care (Liu et al., 2020). The irresponsible use of money and self-destructive behavior was only described in one study (Table 5). Adolescents who were leaving out-of-home care demonstrated low levels of economic wellbeing; more specifically, they showed low financial literacy scores, which reflects difficulties in applying for welfare benefits, using public resources, budgeting, saving habits, being able to use debit and credit cards, and understanding the risk of online shopping (Liu et al., 2020). 2% of adolescent in aftercare reported having problems with intoxication, and this was more common among adolescents who had been in three or more placements (Toivonen et al., 2020).

Discussion

The knowledge base of high-risk behavior among care leavers is currently based on singular studies focusing on substance abuse, criminality, and suicidal behavior (Havlicek et al., 2013; Gypen et al., 2017; Kääriälä & Hiilamo, 2017). For this reason, knowledge on the topic remains sporadic. This review produced a comprehensive overview of the topic by synthesizing previous empirical evidence of how common high-risk behavior is among care leavers, how it manifests, as well as the associated factors. The information in the present review can help practitioners better understand why care leavers develop high-risk behavior, which offers new avenues for future research. This review identified five distinct forms of high-risk behavior, namely, substance abuse, delinquency, sexual behavior, irresponsible use of money, and self-destructive behavior. In contrast, previous reviews have only focused on the outcomes of substance abuse, criminality, and suicidal behavior (Gypen et al., 2017; Havlicek et al., 2013; Kääriälä & Hiilamo, 2017), leaving other forms (e.g., irresponsible use of money) outside of the attention. In addition, none of the previous reviews reported associations between high-risk behavior and background factors, which was done in the current review.

When the findings of this review are compared with what has been reported in studies of high-risk behavior among all adolescents (e.g., Krause et al., 2022; Smith-Grant et al., 2022), it becomes clear that the research of care leavers’ high-risk behavior is limited. Furthermore, the factors associated with high-risk behavior, risk behavior profiles, and causal relationships have been studied more comprehensively among general adolescents than the sub-population of adolescents in out-of-home care (Blankenstein et al., 2020; Goulet et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2021). This leads to the assumption that care leavers exhibit more forms of high-risk behavior than have currently been described due to multiple factors which can predispose them to high-risk behavior (Kobulsky et al., 2022). This shortcoming can be attributed to the fact that care leavers are a difficult group to manage and have commit to research.

However, comprehensive and longitudinal research among care leavers is crucial to increasing our understanding of the developmental trajectories and causal relationships of high-risk behavior in this group (Sariaslan et al., 2022). For example, it has been shown that age at the time of first arrest alters the developmental course of offending (with a younger age having a larger impact), and heightens involvement, frequency, and severity of offending throughout adolescence and early adulthood (Bersani et al., 2022). Also, the fact that substance abuse and delinquency were the most common forms of high-risk behavior in the identified studies emphasizes the need for a comprehensive research approach in the future.

The methodological challenge of research targeted to care leavers is the reliability of self-assessments of high-risk behavior. The self-evaluation of substance abuse via interviews and questionnaires raises concerns about the accuracy of the prevalence and incidence of this behavior due to the provision of socially desirable responses (He et al., 2015). Although surveys and interviews were also used to examine delinquency, official arrest data and registry data were used to strengthen the credibility of the results. Thus, while it is important to pay attention to the authentic expressions of vulnerable adolescents (Dixon et al., 2019), more registry data should be utilized in the research to strengthen the reliability of results and produce generalizable conclusions. Furthermore, the use of registry data enables the authentic description of reality in terms of what services are offered and what adolescents’ needs are without the risk of socially desirable answers. It is also noteworthy that the incidence of high-risk behavior varied noticeably between the identified studies, a dynamic which may be explained by sample size, study design, or cultural considerations (e.g., Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2014).

Approximately half of the studies included in this review described associations between background factors and the prevalence of high-risk behavior, of which some were statistically significant. For example, being male, being placed in out-of-home care three or more times, having been placed in a group home or institutional setting, having run away, and being placed into out-of-home care because of behavioral or emotional problems were connected to a higher risk of substance abuse. These findings are in line with what was reported by Scannapieco et al. (2016) in that the quality of life among adolescents who grew up in out-of-home care was found to be related to type of placement and the number of placements. As high-risk behavior influences an adolescent’s development and quality of life, it would be important to identify the possible connections between background factors and high-risk behavior in order to know how to best support the development of this vulnerable population. The majority of care leavers are resilient and have sufficient mental resources to overcome the challenges they face (Shpiegel et al., 2022); therefore, research on risk behavior should also focus on associations between care leavers’ protective factors and high-risk behavior. Further factors that have been established to enhance the quality of life include educational status, psychological health, and behavioral disorders (e.g., de Oliveira Pinheiro et al., 2022). However, these factors were not examined in the included studies.

It should be noted that previous research has focused on examining how an adolescent’s current socio-economic situation (i.e., housing, and financial situation) affects the prevalence of high-risk behavior. This type of focus means that a care leaver’s childhood life situation and development fall outside of the scope of research. This is not a reliable approach, as both features largely impact an adolescent’s development. Thus, care leavers should always be studied from a holistic perspective, which can be expected to enhance the knowledge base for future service development.

Implications for Future Research and Service Policy

The findings of this review serve as a foundation for further research; more specifically, there should be a focus on the comprehensive identification of various forms of high-risk behavior among adolescents in order to gain insight into how adolescents’ healthy development can be supported and how high-risk behavior can be effectively mitigated. Moreover, research should focus on identifying the connections between high-risk behavior and background factors among care leavers using a variety of data sources, large sample sizes, and distinct research methods, all while taking into account the cultural context. The comprehensive identification of which background factors influence high-risk behavior will provide important information that can be used as a guide for future research, preventive work (via multi-professional collaboration), and policy-makers who can influence the conditions and services provided to out-of-home adolescents. Furthermore, knowledge about an adolescent’s high-risk behavior (including forms and prevalence) and background will increase our understanding of adolescents’ development, high-risk behavior prevention and reduction, as well as adolescents’ needs. This comprehensive overview provides clear guidelines for how vulnerable adolescents can be provided with the correct type of holistic support. When discussing holistic and humane encounters, it is also relevant to examine the resources and protective factors of at-risk adolescents for the best possible chance of preventing these behaviors.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this review are connected to the expertise of the research group and an information specialist at the library. A total of four researchers conducted the research, with two selecting data in every phase and appraising the quality of studies according to validated protocols (Centre for Evidence-Based Management, 2014), while the remaining two researchers supervised the data selection and appraisal phases to confirm accuracy. The inclusion of an information specialist from a library ensured that the search process was systematic and inclusive. A total of six databases were screened for relevant research to obtain a comprehensive overview of the topic. Detailed descriptions of the data retrieval and selection methods increase the transparency of the review.

The limitations of this review were predominantly connected to the gathered data. The identified studies had a rather limited focus: substance abuse and delinquency among adolescents in out-of-home care. The associations between high-risk behavior and background factors were poorly reported, with results on associations limited to a few original studies – mainly originating from the United States – which only drew upon seven individual datasets. These aspects diminish the value of the provided overview of high-risk behavior among care leavers. It should also be stated that most of the presented evidence is of low quality due to weak study designs. The decision to not screen gray literature for relevant research can be considered an additional limitation of the review.

Conclusion

This systematic review gathered the identified forms, prevalence, and associated factors of high-risk behavior among care leavers from previously published research. A total of five distinct forms of high-risk behavior were identified among these adolescents, namely, substance abuse, delinquency, sexual behavior, irresponsible use of money, and self-destructive behavior. Substance abuse and delinquency were the most commonly reported forms of high-risk behavior, with the former mentioned in fourteen studies and the latter mentioned in twelve studies. Adolescents’ sexual behavior were described in three of the articles, while irresponsible use of money and self-destructive behavior were each reported in one study. The included studies provided varying accounts of the incidence of high-risk behavior, which could be attributed to cultural considerations, study design, or sample size. Associations between background factors and high-risk behavior were described in approximately half of the studies, with some findings achieving statistical significance. For instance, gender, race, reason(s) for placement, and the form and number of placements were reported to exert a significant effect on high-risk behavior. Although this review provides an overview of high-risk behavior among care leavers, the topic remains limited. As this review was based on previously reported results, the data and sampling approaches of the included studies could not be influenced. As a result, the data sets underlying the original research focused on only a few forms of high-risk behavior and mean that the present review paints a rather one-sided view of the topic. Moreover, many of the studies adopted a socio-economic perspective when describing the effects of high-risk behavior on care leavers, which does not consider how the past shapes care leavers’ behavior. Identifying the underlying causes of high-risk behavior is critical to supporting the growth and development of these adolescents in a way that does not include high-risk behavior.

References

Akasaki, M., Ploubidis, G. B., Dodgeon, B., & Bonell, C. P. (2019). The clustering of risk behaviours in adolescence and health consequences in middle age. Journal of Adolescence, 77, 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.11.003.

Bersani, B. E., Jacobsen, W. C., & Eggleston Doherty, E. (2022). Does early adolescent arrest alter the developmental course of offending into young adulthood? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51, 724–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01576-7.

Blankenstein, N. E., Telzer, E. H., Do, K. T., van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. K., & Crone, E. A. (2020). Behavioral and neural pathways supporting the development of prosocial and risk-taking behavior across adolescence. Child Development, 91(3), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13292.

Brown, A., Courtney, M. E., & McMillen, J. C. (2015). Behavioral health needs and service use among those who’ve aged-out of foster care. Children and Youth Service Review, 58, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.020.

Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Bates, R., Sayle, M., & Ewart, H. (2020). Gambling with your health: Associations between gambling problem severity and health risk behaviours, health and wellbeing. Journal of Gambling Studies, 36, 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09902-8.

Campbell, R., Wright, C., Hickman, M., Kipping, R. R., Smith, M., Pouliou, T., & Heron, J. (2020). Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence is associated with substantial adverse health and social outcomes in early adulthood: findings from a prospective birth cohort study. Preventive Medicine, 138, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106157.

Center for Evidence Based Management (2014). Critical Appraisal Checklist. Centre for Evidence-based Management. Available at: https://www.cebma.org

Center for Reviews and Dissemination (2009). Systematic reviews CRD, University of York. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

Courtney, M. E., & Hook, J. L. (2017). The potential educational benefits of extending foster care to young adults: findings from a natural experiment. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.030.

Cusick, G. R., Havlicek, J. R., & Courtney, M. E. (2012). Risk for arrest: the role of social bonds in protecting foster youth making the transition to adulthood. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01136.x.

de Oliveira Pinheiro, B., Monezi Andrade, A. L., Lopez, F. M., Reichert, R. A., de Oliveira, W. A., da Becker, A. M., & De Micheli, D. (2022). Association between quality of life and risk behaviors in brazilian adolescents: an exploratory study. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320953472.

Dixon, J., Ward, J., & Blower, S. (2019). “They sat and actually listened to what we think about the care system”: the use of participation, consultation, peer research and co-production to raise the voices of young people in and leaving care in England. Child Care in Practice, 25(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2018.1521380.

Dworsky, A., Napolitano, L., & Courtney, M. (2013). Homelessness during the transition from foster care to adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 318–323. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301455.

Ferrer-Wreder, L., Sugimura, K., Trost, K., Poyrazli, S., Klingstedt, M. L., & Thomas, S. (2014). The intersection of culture, health and risk behaviors in emerging and young adults. The Oxford Handbook of Human Development and Culture: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, 1–13. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199948550.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199948550-e-31

García, B. H., Vázquez, A., Moses, J. O., Cromer, K. D., Morrow, A. S., & Villodas, M. T. (2021). Risk for substance use among adolescents at-risk for childhood victimization: the moderating role of ADHD. Child Abuse & Neglect, 114, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104977.

Glynn, N., & Mayock, P. (2019). “I’ve changed so much within a year”: Care leavers’ perspectives on the aftercare planning process. Child Care in Practice, 25(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2018.1521378.

Goulet, M., Clément, M. E., Helie, S., & Villatte, A. (2020). Longitudinal association between risk profiles, school dropout risk, and substance abuse in adolescence. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49, 687–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09550-9.

Gypen, L., Vanderfaeillie, J., De Maeyer, S., Belenger, L., & Van Holen, F. (2017). Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: systematic-review. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.035.

Hahn, C. K., Hahn, A. M., Simons, R. M., & Caraway, S. J. (2021). Women’s perceived likelihood to engage in sexual risk taking: posttraumatic stress symptoms and poor behavioral regulation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11–12), 5872–5883. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518802851.

Havlicek, J. R., Garcia, A. R., & Smith, D. C. (2013). Mental health and substance use disorders among foster youth transitioning to adulthood: past research and future directions. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.10.003.

He, J., van de Vijver, F. J. R., Dominguez Espinosa, A., Abubakar, A., Dimitrova, R., Adams, B. G., Aydinli, A., Atitsogbe, K., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Bobowik, M., Fischer, R., Jordanov, V., Mastrotheodoros, S., Neto, F., Ponizovsky, Y. J., Reb, J., Sim, S., Sovet, L., Stefenel, D., & Villieux, A. (2015). Socially desirable responding: enhancement and denial in 20 countries. Cross-Cultural Research, 49(3), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397114552781.

Henriksen, M., Skrove, M., Hoftun, G. B., Sund, E. R., Lydersen, S., Tseng, W. L., & Sukhodolsky, D. G. (2021). Developmental course and risk factors of physical aggression in late adolescence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52, 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01049-7.

Häggman-Laitila, A., Salokekkilä, P., & Karki, S. (2018). Transition to adult life of young people leaving foster care: a qualitative systematic review. Children and Youth Service Review, 95, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.017.

Häggman-Laitila, A., Salokekkilä, P., Satka, M., Toivonen, K., Kekolahti, P., & Ryynänen, O. P. (2019). The coping of young finnish adults after out-of-home care and aftercare services: a document-based analysis. Children and Youth Service Review, 102, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.05.009.

Häggman-Laitila, A., Toivonen, K., Puustelli, A., & Salokekkilä, P. (2020). Do aftercare services take young people’s health behavior into consideration? A retrospective document analysis from Finland. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 55, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.08.005.

Kedia, S. K., Dillon, P. J., Jiang, Y., James, W., Collins, A. C., & Bhuyan, S. S. (2021). The association between substance use and violence: results from nationally representative sample of high school students in the United States. Community Mental Health Journal, 57, 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00648-x.

Kelly, P. (2020). Risk and protective factors contributing to homelessness among foster care youth: an analysis of the National Youth in Transition Database. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104589.

Khalil, S. A., Kamal, H., & Elkholy, H. (2022). The prevalence of problematic internet use among a sample of egyptian adolescents and its psychiatric comorbidities. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(2), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020983841.

Kobulsky, J. M., Villodas, M., Yoon, D., Wildfeuer, R., Steinberg, L., & Dubowitz, H. (2022). Adolescent neglect and health risk. Child Maltreatment, 27(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211049795.

Krause, K. H., Mpofu, J., Brown, M., Rico, A., Andrews, C., & Underwood, J. M. (2022). At the intersections: examining trends in experiences of violence, mental health status, and suicidal risk behaviors among US high school students using intersectionality, national youth risk behavior survey, 2015–2019. Journal of Adolescent Health, 71, 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.03.012.

Kääriälä, A., Gyllenberg, D., Sund, R., Pekkarinen, E., Keski-Säntti, M., Ristikari, T., Heino, T., & Sourander, A. (2021). The association between treated psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and out-of-home care among finnish children born in 1997. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01819-1.

Kääriälä, A., & Hiilamo, H. (2017). Children in out-of-home care as young adults: a systematic review of outcomes in the nordic countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.05.030.

Lee, J. Y., Kim, W., Brook, J. S., Finch, S. J., & Brook, D. W. (2020). Adolescent risk and protective factors predicting triple trajectories of substance use from adolescence into adulthood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01629-9.

Lindblad, F., Isaksson, J., Heiskala, V., Koposov, R., & Ruchkin, V. (2020). Comorbidity and behavior characteristics of russian male juvenile delinquents with ADHD and conduct disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(7), 1070–1077. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715584052.

Liu, M., Sun, F., Zhang, S., Tan, S., Anderson, S., & Guo, J. (2020). Youth leaving institutional care in China: Stress, coping mechanisms, problematic behaviors, and social support. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal Online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00698-w

McKenzie, J. E., Brennan, S. E., Ryan, R. E., Thomson, H. J., & Johnston, R. V. (2022). Chapter 9: Summarizing study characteristics and preparing for synthesis. In J.P.T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M.J. Page & V.A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Meeus, W., Vollebergh, W., Branje, S., Crocetti, E., Ormel, J., van de Schoot, R., Crone, E. A., & Becht, A. (2021). On imbalance of impulse control and sensation seeking and adolescent risk: an intra-individual developmental test of the dual systems and maturational imbalance models. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 827–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01419-x.

Mendes, P., & Snow, P. (2016). Young people transitioning from out-of-home care. International research, policy and practice. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mitchell, M. B., Jones, T., & Renema, S. (2015). Will I make it on my own? Voices and visions of 17-year-old youth in transition. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32, 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0364-2.

Murray, A. L., Mirman, J. H., Carter, L., & Eisner, M. (2021). Individual and developmental differences in delinquency: can they be explained by adolescent risk-taking models? Developmental Review, 62, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100985.

Nho, C. R., Park, E. H., & McCarthy, M. L. (2017). Case studies of successful transition from out-of-home placement to young adulthood in Korea. Children and Youth Service Review, 79, 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.035.

Okumura, Y., Yamasaki, S., Ando, S., Usami, M., Endo, K., Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, M., Kasai, K., & Nishida, A. (2021). Psychosocial burden of undiagnosed persistent ADHD symptoms in 12-year-old children: a population-based birth cohort study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(5), 636–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054719837746.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj, 372, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Petrowski, N., Cappa, C., & Gross, P. (2017). Estimating the number of children in formal alternative care: Challenges and results. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.026.

Prince, D. M., Vidal, S., Okpych, N., & Connell, C. M. (2019). Effects of individual risk and state housing factors on adverse outcomes in a national sample of youth transitioning out of foster care. Journal of Adolescence, 74, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.05.004.

Quimby, E. G., Brogan, L., Atte, T., Diamond, G., & Fein, J. A. (2022). Evaluating adolescent substance use and suicide in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care, 38(2), 595–599. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000002453.

Sariaslan, A., Kääriälä, A., Pitkänen, J., Remes, H., Aaltonen, M., Hiilamo, H., Martikainen, P., & Fazel, S. (2022). Long-term health and social outcomes in children and adolescents placed in out-of-home care. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(1), 1–11. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4324.

Scannapieco, M., Smith, M., & Blakeney-Strong, A. (2016). Transition from foster care to independent living: ecological predictors associated with outcomes. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33, 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0426-0.

Shaw, J. (2017). Residential care and criminalisation: the impact of system abuse. Safer Communities, 16(3), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/SC-02-2017-0008.

Shoshani, A., Braverman, S., & Meirow, G. (2021). Video games and close relations: attachment and empathy as predictors of children’s and adolescents’ video game social play and socio-emotional functioning. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106578.

Shpiegel, S., Aparicio, E. M., King, B., Prince, D., Lynch, J., & Grinnell-Davis, C. L. (2020). The functional patterns of adolescent mothers leaving foster care: results from a cluster analysis. Child and Family Social Work, 25(2), 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12704.

Shpiegel, S., & Cascardi, M. (2018). The impact of early childbirth on socioeconomic outcomes and risk indicators of females transitioning out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.001.

Shpiegel, S., Simmel, C., Sapiro, B., & Ramirez Quiroz, S. (2022). Resilient outcomes among youth aging-out of foster care: findings from the national youth in transition database. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 16(4), 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2021.1899098.

Sims-Schouten, W., & Hayden, C. (2017). Mental health and wellbeing of care leavers: making sense of their perspectives. Child and Family Social Work, 22, 1480–1487. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12370.

Smith-Grant, J., Kilmer, G., Brener, N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2022). Risk behaviors and experiences among youth experiencing homelessness- youth risk behavior survey, 23 U.S. states and 11 local school districts, 2019. Journal of Community Health, 47, 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-01056-2.

Song, J., Fogarty, K., Suk, R., & Gillen, M. (2021). Behavioral and mental problems in adolescent with ADHD: exploring the role of family resilience. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.073.

Sultan, R. S., Liu, S. M., Hacker, K. A., & Olfson, M. (2021). Adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: adverse behaviors and comorbidity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68, 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.036.

Tariq, N., & Gupta, V. (2022, July 11). High risk behaviors. Stat Pearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560756/

Tinner, L., Wright, C., Heron, J., Caldwell, D., Campbell, R., & Hickman, M. (2021). Is adolescent multiple risk behaviour associated with reduced socioeconomic status in young adulthood and do those with low socioeconomic backgrounds experience greater negative impact? Findings from two UK birth cohort studies. Bmc Public Health, 21, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11638-3.

Toivonen, K., Salokekkilä, P., Puustelli, A., & Häggman-Laitila, A. (2020). Somatic and mental symptoms, medical treatments and service use in aftercare- Document analysis of Finnish care leavers. Children and Youth Services Review, 114. Online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105079

Tyler, P. M., Thompson, R. W., Trout, A. L., Lambert, M. C., & Synhorst, L. L. (2017). Important elements of aftercare services for youth departing group homes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1603–1613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0673-0.

van Breda, A. D. (2020). Patterns of criminal activity among residential care-leavers in South Africa. Children and Youth Service Review, 109. Online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104706

Willoughby, T., Heffer, T., Good, M., & Magnacca, C. (2021). Is adolescence a time of heightened risk taking? An overview of types of risk-taking behaviors across age groups. Developmental Review, 61, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100980.

Yang, J., McCuish, E. C., & Corrado, R. R. (2017). Foster care beyond placement: offending outcomes in emerging adulthood. Journal of Criminal Justice, 53, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.08.009.

Zinn, A., Palmer, A. N., & Nam, E. (2017). The predictors of perceived social support among former foster youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72, 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.015.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UKP contributed to the study conceptualization and design, performed the literature search, selection of articles and quality appraisal, and drafted the first manuscript; SK participated in the study conceptualization and design, and performed the literature search, selection of articles and quality appraisal; ATM contributed to the study conceptualization and design, and critically revised the manuscript; AHL participated in the study conceptualization and design, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petäjä, UK., Terkamo-Moisio, A., Karki, S. et al. The Prevalence of High-Risk Behavior Among Adolescents in Aftercare Services and Transitioning from Out-of-home Care: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev 8, 323–337 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00198-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00198-1