Abstract

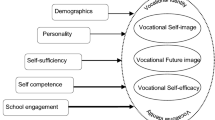

The identification with an occupation is a challenge most adolescents face in their transition into adulthood. Psychosocial development theory suggests that adolescents’ identification with an occupation develops across the lifespan, making youth work roles, choices, and behaviors products of their integrated psychosocial development experiences. This review examines the existing occupational and vocational identity literature to identify the associations with factors relevant to psychosocial development between infancy and adolescence, and integrates them to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how adolescents identify with an occupation. The review reveals that the factors important to healthy psychosocial development in each of Erikson’s five pre-adult stages largely were predictive of occupational identity status in adolescence. Disagreement was present in the literature, with most of it centered on the role of complex outer and environmental factors. The review highlights gaps in the literature and prioritizes areas for future research based largely on a return to Erikson’s intention of treating occupational identity as developmental. The review adds to the current debates and knowledge of youth development and of how adolescents identify with an occupation by providing an integration of the existing empirical evidence not just at the point of adolescence, but also across the entire pre-adult lifespan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The notion of an occupational identity (or, interchangeably, vocational identity) dates back to Erik Erikson’s work (1950, 1968) on the stages of psychosocial development. In his theory of psychosocial development, Erikson (1950, 1968) proposed that choosing an occupation is essential to the achievement of an identity during adolescence. Conversely, it is the inability to settle on an occupational identity that most disturbs young people and prevents them from achieving their adult identity. As technological advances transform the labor market and extend the period between school life and the world of work, Erikson argued, the psychosocial development stage of adolescence has become an even more critical and conscious period for youth. The period of adolescence is thus marked by the challenge that youth face in needing to mutually regulate their sense of who they are and the capacities they have acquired in infancy and childhood with the roles and skills work and adulthood demand of them.

Occupational identity is not so much a concept as it is a construct integral to the formation of an achieved identity (Vondracek 1992). It is interwoven with all of the elements of an achieved identity, and, as such, its development can be traced back to birth. As Erikson postulated (1968), all elements of identity, including the ones that are solidified in later stages of life, are branches rooted to a greater whole and to a single starting point. Occupational identity is not static, but fluid, dynamic, and developmental (Vondracek 1992). It does not emerge haphazardly, but rather, it develops across the lifespan. Its importance to an integrated identity grows and reaches a critical point during adolescence, when youth are expected to independently project themselves imaginatively into the future via a possible occupational path (Kroger and Marcia 2011). In short, without an occupational identity, there is no achieved overall identity, and without an achieved overall identity, there is no psychosocial transition into adulthood.

Toward an Understanding of Occupational Identity

According to Meyer et al. (1993), “occupational identity refers to an individual’s positive assessment of the occupation he/she is engaged in, and it indicates the importance of the occupational role to the individual’s self-identity” (p. 539). Occupations are not merely actions, but roles that are extensions of people’s identity (Super 1957). In other words, identity drives the reasons why individuals choose to perform their occupational roles (Vondracek 1991). Holland et al. (1993) defined vocational identity, on the other hand, as “the possession of a clear and stable picture of one’s goals, interests, and talents” (p. 1). This definition relates to an overall identity in that attaining a vocational identity requires a clear sense of self. One cannot exist without the other. The literature uses the two terms interchangeably in spite of the slight difference in definition because both terms ultimately convey the isomorphic relationship between identity and occupational roles and behaviors.

A significant amount of research has found empirical support for the correlation between high occupational identity status and mature identity formation (Anderson and Mounts 2012; Diemer and Blustein 2006; Dipeolu et al. 2013; Healy and Mourton 1985; Hirschi 2010, 2011a; Robitschek and Cook 1999; Savickas 1985; Vondracek 1995), substantiating Erikson’s theory that choosing an occupation is essential to the achievement of an identity. Skorikov and Vondracek (1998), for example, found amongst 7th and 12th grade students a developmental progression in vocational identity characterized by an increase in the proportion of students classified as identity achieved. Adolescents with a developed occupational identity are more mature, possess more constructive beliefs about career decision-making, and are free of disabling psychological problems (Holland et al. 1993), all of which are key components of an achieved adult identity.

Occupational identity has also been found to precede more advanced statuses in other identity domains, including the political, religious, and lifestyle spheres (Skorikov and Vondracek 1998), elevating its importance to psychosocial development. Occupational identity is typically stronger than other identity domains because occupations are a primary way to communicate one’s identity and provide contexts for identity, because many interpersonal relationships are linked directly to the work role, and because most families are oriented toward work (Mortimer et al. 2014; Phelan and Kinsella 2009). Embedded within these suppositions lie the assumptions that every adolescent has an opportunity to make work choices and that work is a contained part of everyone’s lives (Swanson 2013). To capture these challenges and to gain a thorough understanding of an individual’s occupational identity, it is vital to study its development across the early life stages, not just at the point of adolescence.

Occupational Identity Development Across Erikson’s Pre-Adult Life Stages

Stage 1: Infancy and the Mutuality of Recognition

Encompassing the first 18 months of life, the psychosocial challenge infants must overcome to lay a healthy foundation for future development is to develop a sense of basic trust (Erikson 1950, 1968). Infants’ first social achievement is their willingness to trust that their maternal figure, who has become an inner certainty and an outer predictability to their needs, will consistently and continuously care for them, even when that person is out of sight. It is with a sense of trust that infants begin the lifelong journey of mutual regulation between inner capacities and outer providers to cope with needs, providing meaning to their and to others’ actions. It is this mutuality that encompasses the earliest sense of identity. The amount of trust derived during infancy depends on the quality of the maternal relationship, and without it, or with a weak sense of it, the dystonic outcome is likely to be anxiety, self-debasement, and identity confusion in adolescence (Muuss 1995).

Stage 2: Early Childhood and the Will to be Oneself

It is from a firmly developed early trust that children between the ages of 18 months and 3.5 years begin to develop autonomy and a sense that they are independent individuals who can guide their own futures (Erikson 1950, 1968). The matter of mutual regulation between children and their parental figures faces its severest test during this stage, as children begin to gain large-scale power over themselves and others. The experience of developing a sense of autonomy of free choice must be gradual and well guided, and parents’ firmness must encourage healthy exploration and teach self-control. With excessive parental support or poor family functioning, children may not learn how to regulate experiences of shame and doubt as they explore their developing free wills, which could lead to a loss of self-esteem and self-worth, and to neuroticism and self-consciousness. Too much firmness may lead them to become brash and defiant adolescents, and they may struggle to connect their childhood personality and experiences with a new adult identity (Muuss 1995).

Stage 3: Childhood and the Anticipation of Roles

It is out of a sense of autonomy that children by the end of their third year begin to face the new mutual regulation challenge of developing a sense of parental responsibility and gaining insight into the institutions, functions, and roles that will permit their responsible adult participation (Erikson 1950, 1968). During this stage, children increase their initiative and sense of direction and must learn who they can become, to establish wider goals, and to expand their imagination to many roles, including based on gender norms. Family helps form these basic avenues of vigorous action, teaching children by example their capacities and the direction and purpose of their adult tasks. In doing so, children increase their conscientiousness, self-observation, self-guidance, and self-punishment, and they begin to moderate their own responses to their early failures. According to Muuss (1995), children with low levels of initiative are marked by immobilization and an overdependence on adults.

Stage 4: School Age and Task Identification

From the initiative stage of development, children enter school, and wider society becomes significant in influencing their understanding of meaningful roles in the economy (Erikson 1950, 1968). As children begin to develop a sense of industry, they seek to positively identify with those who know things and know how to do things, and they attach themselves with teachers and other adults to imitate occupations they can grasp. It is in this stage that they begin to develop a sense of work duty, skills, principles, and diligence. They are eager to become a productive unit, to win recognition by producing things, and to begin to be a worker and potential provider. Their heightened awareness of wider society also allows them to recognize how factors such as skin color or parents’ background affect their propensity for feeling worthy. Inadequate development during this stage can lead to adolescent feelings of inadequacy and inferiority, and to estrangement from self, tasks, and skills (Muuss 1995).

Stage 5: Adolescence

According to Erikson (1950, 1968), the establishment of a healthy relationship with the world of industry and the beginning of sexual maturity together lead to the end of childhood and the beginning of adolescence. In their search for a new sense of mutual regulation given these rapid physical and psychosocial changes, adolescents are challenged to independently integrate a meaningful identity in which past, present, and future are unified (Muuss 1995). Their confusion over their sense of self and their quest for self-exploration leads them to become overly concerned with how they appear in the eyes of others and to overidentify with cliques and crowds. The commitment to a system of values and ideologies that they will carry into adulthood also begins to develop during this stage. The major danger is role diffusion, and it is primarily the inability to settle on an occupational identity that leads to such an outcome (Erikson 1950). Adolescents who do not achieve an identity are likely to have unrealistic work goals, to suffer depression, and to withdraw into adverse behaviors and habits (Muuss 1995).

The Current Study

Research has largely treated occupational identity in isolation from broader identity development and in only one stage of development (Vondracek 1991, 1992) in spite of the empirical research substantiating Erikson’s theory that occupational identity is developmental and rooted at birth. Therefore, the objective of this study was to systematically review the piecemeal research into the factors associated with occupational identity, identify the associated factors that are relevant to Erikson’s first five stages of psychosocial development, and integrate them to present a comprehensive review of occupational identity development in adolescence. The results help fill the gap given the lack of longitudinal research in this area and provide the foundation for future research so that it is no longer too simplistic or reductionistic.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted to establish the relationship between occupational and vocational identity and factors relevant to Erikson’s first five stages of development.

Search Strategy

A search was conducted in October 2014 and in March 2016 using the following databases and journals: PsycINFO, SAGE Journals, and Science Direct, and Adolescence, The Career Development Quarterly, Identity, the Journal of Career Assessment, the Journal of Career Development, the Journal of Counseling Psychology, the Journal of Occupational Science, the Journal of Youth and Adolescence, and the Journal of Vocational Behavior. The review consisted of studies that examined the relationship between occupational and vocational identity and factors that are critical to psychosocial development from birth to adolescence. The terms used in the search included occupational identity and vocational identity in both the abstract and full text fields. The abstracts were screened using the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

The following criteria were considered for inclusion in the systematic review: the study should have (1) been peer-reviewed; (2) been published in or translated into the English language; (3) treated occupational identity or vocational identity as a variable; and (4) identified an association with a factor relevant to at least one of Erikson’s first five stages of development.

Methods of the Review

The search process is outlined in Fig. 1. The initial search, excluding duplicates and non-peer-reviewed articles, yielded 531 articles for the keywords occupational identity and vocational identity. Subsequent to the searches, the abstracts of the articles were screened for eligibility and a sample of 357 studies was identified. Next, the full texts of these articles were independently reviewed and assessed three separate times for eligibility. Studies that researched clusters of factors that were relevant to more than one development stage were also removed to avoid confounding issues. A total of 81 articles were finally selected for inclusion.

Methodological Quality Approval

Although only the author assessed the literature, a table (Table 1) summarizing the key tenets of Erikson’s first five stages of development was utilized to assess the eligibility of each article and to identify the relevant development stage of each factor found to be associated with occupational or vocational identity. The 357 articles that passed the initial screening were also reviewed three times between October 2014 and March 2016 to strengthen objectivity.

Data Extraction

A data extraction table (Table 2) was drawn up using Davids and Roman’s (2014) data extraction tool. The information in the data extraction table included author, geographic location, study design, participants, variable(s) of interest, association/relationship between variable(s) of interest and occupational identity or vocational identity, and relevant stage.

Results

Overview of Reviewed Studies

As expected, the number of identified associations increased across Erikson’s first five stages of development (Table 1). These findings reflect the large focus of the occupational identity research on the adolescence stage of development and on factors that are more directly related to the world of work, such as career decision-making skills. The final sample of 81 studies included in the systematic review consisted of 65 cross-sectional studies and 16 longitudinal studies ranging from 2 weeks to 3 years. Of the studies that reported the ages of participants, the youngest age was 12 years and the oldest was 53 years.

Associations with Occupational Identity

Stage 1: Infancy and the Mutuality of Recognition

Anxiety

Two findings relevant to the quality of the maternal relationship and the ability to develop a basic sense of trust and endure anxieties were identified. Lopez (1989) found for both male and female participants that emotional independence from the mother was negatively correlated with trait anxiety, and that such anxiety contributed to vocational identity concerns during late adolescence. Healy (1991) found that anxiety interfered with the acquiring of vocational identity by disrupting the experiences in which it develops and also reported that anxiety and vocational identity were both directly and indirectly linked.

Stage 2: Early Childhood and the Will to be Oneself

Family organization and parental support and firmness

Five findings relevant to family organization and to parental firmness were identified. Blinne and Johnston (1998) and Johnson et al. (1999) reported no significant differences in vocational identity based on parents’ marital status. Nonetheless, Berríos-Allison (2005) did find that participants who themselves had experienced early separation from their parents were less achieved in occupational identity. Participants from families that were supportive and that encouraged occupational exploration and commitments were the most achieved in occupational identity. Meeus and Dekovic (1995) also reported that parental support had an additive influence on occupational identity development, and that participants with an unachieved occupational identity were from more intrusive and controlling families. Nonetheless, Hargrove et al. (2002) found that family organization and family enforcement of rules were not significant predictors for vocational identity.

Exploration and parent–child congruence

Five findings regarding occupational exploration and parental agreement were identified. Vondracek and Skorikov (1997) identified a significant positive correlation between occupational exploration and vocational identity achievement, and Gushue et al. (2006) found that a perception of fewer barriers related to career exploration was related to a more integrated vocational identity. Carpe and Becker (1957) reported that occupational identity conflict occurred when disparities between parental and occupational expectations were present. Similarly, Nauta (2012) found that participants’ vocational identity was associated with career interest agreement with their parents, and Song et al. (2016) reported that participants in occupational identity exploration status also experienced low inter-parental conflict.

Independence, locus of control, self-esteem, and neuroticism

Five findings relevant to factors that are critical to healthy development during Erikson’s second stage of psychosocial development were identified. Graef et al. (1985) reported that out of 103 males, the ones possessing a clear vocational identity were differentiated as not being too strongly independent or dominant. Dellas and Jernigan (1987) found that more internally controlled males were achieved in occupational identity, whereas their more externally controlled peers were diffused in occupational identity. Furthermore, Munson (1992) reported that participants with high self-esteem scored significantly higher on vocational identity. Hirschi (2012) identified a relationship between higher neuroticism and the emergence of vocational identity exploration over time, and, similarly, Hirschi and Herrmann (2013) found a positive relationship between neuroticism and more problems in vocational identity.

Stage 3: Childhood and the Anticipation of Roles

Family functioning

Five studies regarding factors related to perceptions of the usefulness of family behavioral patterns in achieving objectives were identified. Penick and Jepsen (1992) found that family members’ perception of family functioning significantly predicted participants’ vocational identity. Similarly, Johnson et al. (1999) and Song et al. (2016) respectively reported that family functioning, cohesion, and expressiveness were related to vocational identity, with expressiveness being the most predictive, and that high functional family communication positively influenced occupational identity in achievement status. Nonetheless, Hartung et al. (2002) found no association between vocational identity and perceived levels of cohesion and adaptability within the family, and Shin and Kelly (2013) found that family cohesion and expressiveness moderated the link between optimism and vocational identity for Korean but not American participants.

Motivation, purpose, and self-efficacy

Six studies relevant to the foundation for initiative were identified, all of which reported positive associations with occupational identity. Waterman and Waterman (1976) reported that intrinsic motivation was more related to vocational identity than extrinsic motivation, and Kivlighan and Shapiro (1987) found that participants with realistic, investigative, or conventional sense high-point codes showed greater changes in vocational identity after a career counseling course compared to those with artistic, social, or enterprising ones. Turning to self-efficacy, Gushue et al. (2006a, b) respectively reported that greater self-efficacy was related to a more differentiated vocational identity for Latinos and for Blacks. Jantzer et al. (2009) found that participants with higher levels of career decision-making self-efficacy were more likely to have an achieved vocational identity, and Hammond et al. (2010) identified vocational identity as a clear self-efficacy factor.

Mental maturation measures

Four studies relevant to measures of the mental maturation needed to undertake initiative were identified, all of which reported positive associations with occupational identity. Robitschek and Cook (1999) found that participants with higher levels of personal growth initiative were likely to have a more crystallized vocational identity. Hirschi identified a positive association between a more crystallized vocational identity and greater orientation toward meaning and career engagement and away from pleasure (2011a), as well as a relationship between conscientiousness and maintaining or achieving a vocational identity (2012). Ahn et al. (2015) reported that higher occupational identity statuses were significantly related to the cluster of curiosity, persistence, flexibility, optimism, and risk taking skills.

Gender roles

Two studies regarding how perceptions of gender roles and masculinity are related to occupational identity were identified. Vaz (1968) found no association between the vocational identity status of males and their ranking of nursing based on masculinity level. Grotevant and Thorbecke (1982), however, reported that vocational identity for both males and females was positively related to self-perceptions of masculinity traits, but not to those of femininity.

Stage 4: School Age and Task Identification

Ethnic and socioeconomic group membership

Six findings were identified that discussed a correlation between occupational identity and ethnic and socioeconomic background. Jackson and Neville (1998) reported that strong and affirmative racial identity attitudes accounted for a significant amount of variability in the vocational identity of Black females but not males. Leong (1991) found no cultural group differences in vocational identity between Anglo and Asian American participants, whereas Abraham (1986) reported that Mexican American participants were more foreclosed in their occupational identity than their Anglo American peers regardless of socioeconomic status. A New Zealand study found that more Anglo participants than indigenous ones had achieved an occupational identity, regardless of socioeconomic status (Chapman and Nicholls 1976). Solomontos-Kountouri and Hurry (2008) reported that upper-class participants were less likely to be in occupational identity diffusion status, whereas working-class participants were more likely. Nonetheless, Lindstrom et al. (2007) found that belonging to a low socioeconomic status family bolstered vocational identity development by motivating stable employment.

Academic and school ability and attitudes

Nine studies that researched a correlation between occupational identity and academic ability and school experiences were identified. Meeus (1993) found that participants who performed well at school had a stronger occupational identity than those whose school performance was poor, and Ochs and Roessler (2001) reported that special education students had significantly lower vocational identity scores than their general education peers. Lapan et al. (1993) found that changes in perceived mastery of guidance competencies predicted increases in English grades and vocational identity for females. Graef et al. (1985) identified a correlation in females between a weak vocational identity and poor grade point average and a negative academic attitude, and Lopez (1989) similarly reported that academic adjustment difficulties set the stage for vocational identity concerns during late adolescence. Coutinho and Blustein (2014) found that vocational identity protected participants from school disengagement.

Nonetheless, three studies found no association between occupational identity and academic ability factors. Chapman and Nicholls (1976) reported no relationship between occupational identity and intelligence quotient, and Kelly (1992) similarly found that gifted students were not higher in vocational identity than their regular curriculum peers. Healy et al. (1990) were unable to identify a correlation between vocational identity and participants’ awareness of academic ability or grade point average.

Activities and work interest

Four studies researched the relationship between occupational identity and activities and work interests. Although Meeus (1993) found no correlation with leisure-time behavior, a study that specified the activities as more intellectual and creative reported that those who participated more in them were more advanced in occupational identity achievement (Munson and Widmer 1997). Similarly, Graef et al. (1985) identified amongst females a relationship between few high school and cultural activities and the lacking of a clear vocational identity. Vondracek and Skorikov (1997) found a significant positive correlation between occupational identity achievement and interest in work.

Goal formation and stability

Three studies researched the association between occupational identity and the ability to make goals and to maintain them, and all found it to be significant and positive. Savickas (1985) found that vocational identity was related to having a clearer picture of vocational goals, abilities, and talents. Santos (2003) reported that goal instability was a significant predictor of a weak vocational identity, and Hammond et al. (2010) found that vocational identity development centered on having more stable personal goals.

Ability to overcome obstacles

Three studies were identified that researched the ability to solve problems and overcome barriers, and all found a positive correlation with occupational identity achievement. Sweeney and Schill (1998) found that participants who scored higher on a self-defeating personality scale indicated a poorer sense of vocational identity. Similarly, Diemer and Blustein (2006) reported that participants with a greater ability to recognize and overcome sociopolitical barriers had a clearer vocational identity, and Henry (1996) identified a positive correlation between participants’ problem-solving appraisal and their vocational identity.

Stage 5: Adolescence

Peer group membership

Five studies reported findings into how peer group membership affects occupational identity development. Becker and Carper (1956) found that participation in various kinds of organized groups, including peer groups and student cliques, affected experience and, through it, changes in the identification with an occupation. Johnson (1987) also reported correlations between membership in social crowds and vocational identity scores. For example, nerds scored highest on investigative vocational interests, whereas freaks scored highest on artistic ones. Meeus and Dekovic (1995) identified peers as highly influential on participants’ occupational identity development, and Song et al. (2016) found that high peer attachment in foreclosure status and low peer attachment in diffusion status positively influenced the level of vocational identity. Nauta (2012), however, was unable to find a relationship between vocational identity and peer agreement with respect to career interests.

Integration of self-knowledge

Four studies discussed the relationship between occupational identity and measures related to the integration of self-knowledge, all of which found positive associations. Johnson et al. (2014) reported that higher levels of strong sense of self predicted higher levels of vocational identity. Graef et al. (1985) similarly found that the male participants who possessed a clear vocational identity were socially well adjusted. Konik and Stewart (2004) identified a relationship between identifying as a sexual minority and having more advanced occupational identity development. Finally, Taber and Blankemeyer (2015) reported that diffused vocational identity status was associated with negative views of the past and lower orientation toward the future, whereas an achieved one was related to a hedonic view of the present and with being more mindful.

Career decision-making abilities

Eight studies that reported on the correlation between occupational identity and career decision-making abilities were identified. Conneran and Hartman (1993) and Larson et al. (1994) both found vocational identity development to be negatively correlated with career indecidedness. Long et al. (1995) reported a positive relationship between vocational identity and career decidedness, and Jantzer et al. (2009) identified one with career decision-making intentions and goals. Hirschi and Läge (2007) reported that vocational identity emerged as a direct measure for career choice readiness attitudes, and Hammond et al. (2010) found that vocational identity development centered on greater levels of career decisiveness. Graef et al. (1985) identified a relationship in females between lacking a clear vocational identity and having an undeclared major. Whereas Leung (1998) similarly found that vocational identity was related to college major choice congruence, he was unable to report a similar relationship for career choice congruence.

Career choice readiness measures

Nine studies reported findings regarding the relationship between occupational identity and various measures significant for career choice readiness. Dipeolu et al. (2013) found that career maturity scores predicted vocational identity. Studies also reported a positive correlation with career development skills (Hirschi 2010; Sung et al. 2012), commitment to career choices (Diemer and Blustein 2007; Ladany et al. 1997), and differentiation of vocational interests (Hirschi 2011b; Im 2011). Nonetheless, Healy et al. (1990) and Hirschi and Läge (2008b) were unable to correlate vocational identity with participants’ college enrollment plans or to their coherence of career aspirations, respectively.

Career development treatments

Sixteen studies researched the effects of career development interventions on changes in occupational identity, 13 of which were longitudinal and all of which reported that the treatment was successful. Such interventions included a career development course (Farley et al. 1988; Henry 1993; Johnson et al. 2002; Rayman et al. 1983; Remer et al. 1984; Scott and Ciani 2008; Thomas and McDaniel 2004) or seminar (Johnson et al. 1981), a computerized career course (Mau 1999; Shahnasarian and Peterson 1988), a career workshop (Hirschi and Läge 2008a; Merz and Szymanski 1997), self-help career counseling (Kivlighan and Shapiro 1987), and a job search club for international graduate students (Bikos and Furry 1999). Gold et al. (1993) reported that feelings of support and encouragement accounted for most of the explained variance in positive changes in vocational identity amongst participants in career exploration classes, and Lapan et al. (1993) found that changes in participants’ perceived mastery of guidance competencies after a joint career development and writing skills course predicted positive changes in vocational identity.

Discussion

The current review found that the majority of the existing empirical research substantiated the notion that occupational identity is associated with the development skills learned across Erikson’s (1950, 1968) pre-adult stages, and that not attaining the development skills in the appropriate stage can lead to negative consequences for occupational identity development in later stages. In spite of both the breadth and depth of Erikson’s psychosocial development theory and his perspective on how an occupational identity emerges throughout this process, the current review found a good level of agreement in the empirical research throughout the five pre-adult stages of psychosocial development. This finding challenges the notion that work roles, choices, and behaviors are sole products of adolescence, and it urges academics interested in youth work outcomes to not limit their research to adolescence or adulthood, but, rather, to expand it to include individuals’ psychosocial realities across their pre-adult lifespan.

How Does Occupational Identity Develop from Infancy to Adolescence?

The examination of the factors associated with occupational and vocational identity that are also relevant to Erikson’s (1950, 1968) five pre-adult stages of psychosocial development revealed that occupational identity generally develops from infancy to adolescence as proposed in Erikson’s theory. Occupational identity development is a process of mutual regulation between individuals’ inner needs and capacities and the outer opportunities their environment provides. The current review revealed that there is little to no empirical disagreement regarding the role of various inner needs and capacities, including: parental attachment and support; parent–child occupational exploration congruence; independence, locus of control, and self-esteem; motivation, purpose, and self-efficacy, mental maturation; goal formation and stability; ability to overcome obstacles; ability to integrate self-knowledge; and capacity to make career decisions.

The majority of the areas in which there was more empirical disagreement were, notably, those that consist of the outer components of the process of mutual regulation. As a result, there is less empirical certainty in what is known about how the intersection of individuals and their outer environments influences occupational identity development from infancy to adolescence, including: parental firmness and family functioning; perceptions and expectations based on gender and ethnic background; socioeconomic status; academic abilities and school experiences; and leisure activities and interests. These factors are unquestionably much more complex and difficult to measure than individual inner needs and capacities, which challenges the ability of empirical research to agree on a clear understanding of their role in occupational identity development. And although the empirical disagreement over these outer factors demands further research, the current review did identify significant examples of evidence to suggest that Erikson (1950, 1968) was once again correct in positing that healthy and balanced levels of these factors are positively associated with occupational identity development.

What is not known at all about how occupational identity develops from infancy to adolescence is how these inner and outer factors interact with each other across the pre-adult lifespan and what other factors not included in Erikson’s (1950, 1968) psychosocial development theory are important to such development. Most of the studies in the current review were cross-sectional, and the majority of the available longitudinal studies simply tested for the before and after effects of career development interventions on occupational identity, severely limiting the understanding of occupational identity development to a simplistic and reductionistic one. Furthermore, as Erikson himself predicted, structural and institutional changes in society and in the labor market have fundamentally altered psychosocial development from infancy to adolescence, and these realities are not captured in the current literature.

Limitations and Recommendations

The current review treated the notion of occupational identity as developmental and sought to identify and integrate the factors associated with it across Erikson’s pre-adult stages of psychosocial development given the lack of longitudinal research. Yet, the current review is ultimately a product of the literature itself, and while it has integrated the findings into a single timeline encompassing infancy through adolescence, it remains a sum of piecemeal findings that treated occupational identity as simplistic and reductionistic and that often relied on participants already in their adult years. These limitations, however, should not overcome the fact that without longitudinal research that spans the pre-adult lifetime, the current review offers the most comprehensive illustration of how occupational identity develops between infancy and adulthood based not just on theory, but on empirical evidence. Indeed, the limitations of the current review should act as a reminder to academics of what their future research should look like.

Four critical recommendations for future research emerge from the current review. The first is to conduct longitudinal studies to ensure the treatment of occupational identity as developmental and rooted to a greater whole, as Erikson (1950, 1968) intended. In lieu of this, retrospective studies in which adolescents are asked to recall their psychosocial development from their infancy to current time could be conducted. Second, qualitative research was scant in the current review, yet it is well positioned to allow researchers to gather comprehensive data and to generalize findings to theory (Maxwell 2013), essentially testing its strength. Such research could also help expand on Erikson’s theory by capturing missing factors that are nonetheless pertinent to occupational identity development. Third, future research should focus on studying the role of complex outer factors in occupational identity development, as well as undertake methods that could gather changes in psychosocial development in today’s modern society, as much has changed since Erikson formulated his theory in 1950 and 1968. Finally, future research should diversify sampling, particularly based on ethnicity and class, to be more representative of the US and world youth populations.

Conclusion

Adolescents’ identification with an occupation develops across their pre-adult lifespan, making their work roles, choices, and behaviors products of their integrated psychosocial development experiences. This review examined existing findings into the factors associated with occupational identity that are relevant to Erikson’s pre-adult stages of psychosocial development to help fill in the gap given the lack of longitudinal research into this topic. The results indicate that the factors important to healthy psychosocial development in each of Erikson’s five pre-adult stages were largely predictive of occupational identity status in adolescence. Disagreement was present in the empirical evidence, with most of it centered on complex outer factors such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Nonetheless, sufficient findings were also identified to suggest that Erikson’s theory likely holds true for these factors.

The current review provides the first comprehensive understanding of the associations between occupational identity and psychosocial development factors across Erikson’s five pre-adult stages of psychosocial development. The review provides clear categories of Erikson’s most important psychosocial development factors in each of the five stages and a summary of the empirical research into their association with occupational identity. In doing so, the review additionally proposes recommendations for future research that reinforce Erikson’s initial conceptualization of occupational identity and prioritize the existing literature’s weakest points to finally begin to gain a developmental understanding of adolescents’ identification with an occupation.

References

Abraham, K. G. (1986). Ego-identity differences among Anglo-American and Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 9(2), 151–166.

Ahn, S., Jung, S. H., Jang, S. H., Du, X., Lee, B. H., Rhee, E., et al. (2015). Planned happenstance skills and occupational identity status in high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 63(1), 31–43.

Anderson, K. L., & Mounts, N. S. (2012). Searching for the self: An identity control theory approach to triggers of occupational exploration. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 173(1), 90–111.

Becker, H. S., & Carper, J. W. (1956). The development of identification with an occupation. American Journal of Sociology, 61(4), 289–298.

Berríos-Allison, A. C. (2005). Family influences on college students’ occupational identity. Journal of Career Assessment, 13(2), 233–247.

Bikos, L. H., & Furry, T. S. (1999). The job search club for international students: An evaluation. The Career Development Quarterly, 48(1), 31–44.

Blinne, W. R., & Johnston, J. A. (1998). Assessing the relationship between vocational identity, academic achievement, and persistence in college. Journal of College Student Development, 39(6), 569–576.

Carper, J. W., & Becker, H. S. (1957). Adjustments to conflicting expectations in the development of identification with an occupation. Social Forces, 36(1), 51–56.

Chapman, J. W., & Nicholls, J. G. (1976). Occupational identity status, occupational preferences, and field dependence in Maori and Pakeha boys. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 7(1), 61–72.

Conneran, J. M., & Hartman, B. W. (1993). The concurrent validity of the self directed search in identifying chronic career indecision among vocational education students. Journal of Career Development, 19(3), 197–208.

Coutinho, M. T., & Blustein, D. L. (2014). Cape Verdean immigrants’ career development and school engagement: Perceived discrimination as a moderator. Journal of Career Development, 41(4), 341–358.

Davids, E. L., & Roman, N. V. (2014). A systematic review of the relationship between parenting styles and children’s physical activity. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 20(Suppl 2:1), 228–246.

Dellas, M., & Jernigan, L. P. (1987). Occupational identity status development, gender comparisons, and internal-external control in first-year air force cadets. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(6), 587–600.

Diemer, M. A., & Blustein, D. L. (2006). Critical consciousness and career development among urban youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 220–232.

Diemer, M. A., & Blustein, D. L. (2007). Vocational hope and vocational identity: Urban adolescents’ career development. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(1), 98–118.

Dipeolu, A., Sniatecki, J. L., Storlie, C. A., & Hargrave, S. (2013). Dysfunctional career thoughts and attitudes as predictors of vocational identity among young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(2), 79–84.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Farley, R. C., Schriner, K. F., & Roessler, R. T. (1988). The impact of the occupational choice strategy on the career development of rehabilitation clients. Rehabilitation Psychology, 33(2), 121–125.

Gold, P. B., Kivlighan, D. M., Kerr, A. E., & Kramer, L. A. (1993). Structure of students’ perceptions of impactful, helpful events in career exploration classes. Journal of Career Assessment, 1(2), 145–161.

Graef, M. I., Wells, D. L., Hyland, A. M., & Muchinsky, P. M. (1985). Life history antecedents of vocational indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 27(3), 276–297.

Grotevant, H. D., & Thorbecke, W. L. (1982). Sex differences in styles of occupational identity formation in late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 18(3), 396–405.

Gushue, G. V., Clarke, C. P., Pantzer, K. M., & Scanlan, K. R. L. (2006a). Self-efficacy, perceptions of barriers, vocational identity, and the career exploration behavior of Latino/a high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 54(4), 307–317.

Gushue, G. V., Scanlan, K. R. L., Pantzer, K. M., & Clarke, C. P. (2006b). The relationship of career decision-making self-efficacy, vocational identity, and career exploration behavior in African American high school students. Journal of Career Development, 33(1), 19–28.

Hammond, M. S., Lockman, J. D., & Boling, T. (2010). A test of the tripartite model of career indecision of Brown and Krane for African Americans incorporating emotional intelligence and positive affect. Journal of Career Assessment, 18(2), 161–176.

Hargrove, B. K., Creagh, M. G., & Burges, B. L. (2002). Family interaction patterns as predictors of vocational identity and career decision-making self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(2), 185–201.

Hartung, P. J., Lewis, D. M., May, K., & Niles, S. G. (2002). Family interaction patterns and college student career development. Journal of Career Assessment, 10(1), 78–90.

Healy, C. C. (1991). Exploring a path linking anxiety, career maturity, grade point average, and life satisfaction in a community college population. Journal of College Student Development, 32(3), 207–211.

Healy, C. C., & Mourton, D. L. (1985). Congruence and vocational identity: Outcomes of career counseling with persuasive power. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32(3), 441–444.

Healy, C. C., Tullier, M., & Mourton, D. M. (1990). My vocational situation: Its relation to concurrent career and future academic benchmarks. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 23(3), 100–107.

Henry, P. (1993). Effectiveness of career-development courses for nontraditional premedical students: Improving professional identity. Psychological Reports, 73(3 Pt 1), 915–920.

Henry, P. (1996). Perceived problem-solving and vocational identity: Implication for nontraditional premedical students. Psychological Reports, 78(3 Pt 1), 843–847.

Hirschi, A. (2010). Individual predictors of adolescents’ vocational interest stabilities. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 10(1), 5–19.

Hirschi, A. (2011a). Effects of orientations to happiness on vocational identity achievement. The Career Development Quarterly, 59(4), 367–378.

Hirschi, A. (2011b). Relation of vocational identity statuses to interest structure among Swiss adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 38(5), 390–407.

Hirschi, A. (2012). Vocational identity trajectories: Differences in personality and development of well-being. European Journal of Personality, 26(1), 2–12.

Hirschi, A., & Herrmann, A. (2013). Assessing difficulties in career decision-making among Swiss adolescents: Evaluation of the German my vocational situation scale. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 72(1), 33–42.

Hirschi, A., & Läge, D. (2007). Holland’s secondary constructs of vocational interests and career choice readiness of secondary students. Journal of Individual Differences, 28(4), 205–218.

Hirschi, A., & Läge, D. (2008a). Increasing the career choice readiness of young adolescents: An evaluation study. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 8(2), 95–110.

Hirschi, A., & Läge, D. (2008b). Using accuracy of self-estimated interest types as a sign of career choice readiness in career assessment of secondary students. Journal of Career Assessment, 16(3), 310–325.

Holland, J. L., Johnston, J. A., & Asama, N. F. (1993). The vocational identity scale: A diagnostic and treatment tool. Journal of Career Assessment, 1(1), 1–12.

Im, S. (2011). The effect of profile elevation on the relationship between interest differentiation and vocational identity. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 39(2), 149–160.

Jackson, C. C., & Neville, H. A. (1998). Influence of racial identity attitudes on African American college students’ vocational identity and hope. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 53(1), 91–113.

Jantzer, A. M., Stalides, D. J., & Rottinghaus, P. J. (2009). An exploration of social cognitive mechanisms, gender, and vocational identity among eighth graders. Journal of Career Development, 36(2), 114–138.

Johnson, P. A. (1987). Influence on adolescent social crowds on the development of vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(2), 182–199.

Johnson, P., Buboltz, W. C., & Nichols, C. N. (1999). Parental divorce, family functioning, and vocational identity of college students. Journal of Career Development, 26(2), 137–146.

Johnson, P., Nichols, C. N., Buboltz, W. C., & Riedesel, B. (2002). Assessing a holistic trait and factor approach to career development of college students. Journal of College Counseling, 5(1), 4–14.

Johnson, P., Schamuhn, T. D., Nelson, D. B., & Buboltz, W. C. (2014). Differentiation levels of college students: Effects on vocational identity and career decision making. The Career Development Quarterly, 62, 70–80.

Johnson, J. A., Smither, R., & Holland, J. L. (1981). Evaluating vocational interventions: A tale of two career development seminars. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(2), 180–183.

Kelly, K. (1992). Career maturity of young gifted adolescents: A replication study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 16(1), 36–45.

Kivlighan, D. M., & Shapiro, R. M. (1987). Holland type as a predictor of benefit from self-help career counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34(3), 326–329.

Konik, J., & Stewart, A. (2004). Sexual identity development in the context of compulsory heterosexuality. Journal of Personality, 72(4), 815–844.

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (Vol. 1 and 2, pp. 31–53). New York: Springer.

Ladany, N., Melincoff, D. S., Constantine, M. G., & Love, R. (1997). At-risk urban high school students’ commitment to career choices. Journal of Counseling and Development, 76(1), 45–52.

Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N., Hughey, K., & Arni, T. J. (1993). Evaluating a guidance and language arts unit for high school juniors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 71(4), 444–451.

Larson, L. M., Toulouse, A. L., Ngumba, W. E., Fitzpatrick, L. A., & Heppner, P. P. (1994). The development and validation of coping with career indecision. Journal of Career Assessment, 2(2), 91–110.

Leong, F. T. (1991). Career development attributes and occupational values of Asian American and White American college students. The Career Development Quarterly, 39(3), 221–230.

Leung, A. S. (1998). Vocational identity and career choice congruence of gifted and talented high school students. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 11(3), 325–335.

Lindstrom, L., Doren, B., Metheny, J., Johnson, P., & Zane, C. (2007). Transition to employment: Role of the family in career development. Exceptional Children, 73(3), 348–366.

Long, B. E., Sowa, C. J., & Niles, S. G. (1995). Differences in student development reflected by the career decisions of college seniors. Journal of College Student Development, 36(1), 47–52.

Lopez, F. G. (1989). Current family dynamics, trait anxiety, and academic adjustment: Test of a family-based model of vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 35(1), 76–87.

Mau, W. (1999). Effects of computer-assisted career decision making on vocational identity and career exploratory behaviors. Journal of Career Development, 25(4), 261–274.

Maxwell, J. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Sage Publications.

Meeus, W. (1993). Occupational identity development, school performance, and social support in adolescents: Findings of a Dutch study. Adolescence, 28(112), 809–818.

Meeus, W., & Dekovic, M. (1995). Identity development, parental and peer support in adolescence: Results of a national Dutch survey. Adolescence, 30(120), 931–944.

Merz, M. A., & Szymanski, E. M. (1997). Effects of a vocational rehabilitation-based career workshop on commitment to career choice. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 41(2), 88–104.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conception. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551.

Mortimer, J. T., Lam, J., & Lee, S. (2014). Transformation, erosion, or disparity in work identity? Challenges during the contemporary transition to adulthood. In K. C. McLean & M. Syed (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 319–336). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Munson, W. W. (1992). Self-esteem, vocational identity, and career salience in high school students. Career Development Quarterly, 40(4), 361–368.

Munson, W. W., & Widmer, M. A. (1997). Leisure behavior and occupational identity in university students. The Career Development Quarterly, 46(2), 190–198.

Muuss, R. E. (1995). Erik Erikson’s theory of identity development. In R. E. Muuss (Ed.), Theories of adolescence (pp. 42–57). San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill.

Nauta, M. M. (2012). Are RIASEC interests traits? Evidence based on self-other agreement. Journal of Career Assessment, 20(4), 426–439.

Nevill, D. D., Neimeyer, G. J., Probert, B., & Fukuyama, M. (1986). Cognitive structures in vocational information processing and decision making. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 28(2), 11–122.

Ochs, L. A., & Roessler, R. T. (2001). Students with disabilities: How ready are they for the 21st century? Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 44(3), 170–176.

Penick, N. I., & Jepsen, D. A. (1992). Family functioning and adolescent career development. The Career Development Quarterly, 40(3), 208–222.

Phelan, S., & Kinsella, E. A. (2009). Occupational identity: Engaging socio-cultural perspectives. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(2), 85–91.

Rayman, J. R., Bernard, C. B., Holland, J. L., & Barnett, D. C. (1983). The effects of a career course on undecided college students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 23(3), 346–355.

Remer, P., O’Neill, C. D., & Gohs, D. E. (1984). Multiple outcome evaluation of a life-career development course. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(4), 532–540.

Robitschek, C., & Cook, S. W. (1999). The influence of personal growth initiative and coping styles on career exploration and vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(1), 127–141.

Santos, P. J. (2003). Goal instability, self-esteem, and vocational identity of high school Portuguese students. Análise Psicológica, 21(2), 229–238.

Savickas, M. L. (1985). Identity in vocational development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 27(3), 329–337.

Scott, A. B., & Ciani, K. D. (2008). Effects of an undergraduate career class on men’s and women’s career decision-making self-efficacy and vocational identity. Journal of Career Development, 34(3), 263–285.

Shahnasarian, M., & Peterson, G. W. (1988). The effect of a prior cognitive structuring intervention with computer-assisted career guidance. Computers in Human Behavior, 4(2), 125–131.

Shin, Y., & Kelly, K. R. (2013). Cross-cultural comparison of the effects of optimism, intrinsic motivation, and family relations on vocational identity. The Career Development Quarterly, 61(2), 141–160.

Skorikov, V. B., & Vondracek, F. W. (1998). Vocational identity development: Its relationship to other identity domains and to overall identity development. Journal of Career Assessment, 6(1), 13–35.

Solomontos-Kountouri, O., & Hurry, J. (2008). Political, religious, and occupational identities in context: Placing identity status paradigm in context. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 241–258.

Song, B., Kim, D. W., & Lee, K. (2016). Contextual influences on Korean college students’ vocational identity development. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(1), 175–184.

Sung, Y., Turner, S. L., & Kaewchinda, M. (2012). Career development skills, outcomes, and hope among college students. Journal of Career Development, 40(2), 127–145.

Super, D. E. (1957). Vocational development: A framework for research. New York, NY: Columbia University.

Swanson, J. L. (2013). Traditional and emerging career development theory and the psychology of working. In D. L. Blustein (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the psychology of working (pp. 49–70). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sweeney, M. L., & Schill, T. R. (1998). The association between self-defeating personality characteristics, career indecision, and vocational identity. Journal of Career Assesssment, 6(1), 69–81.

Taber, B. J., & Blankemeyer, M. S. (2015). Time perspective and vocational identity statuses of emerging adults. The Career Development Quarterly, 63(2), 113–125.

Thomas, J. H., & McDaniel, C. R. (2004). Effectiveness of a required course in career planning for psychology majors. Teaching of Psychology, 31(1), 22–27.

Vaz, D. (1968). High school senior boys’ attitudes toward nursing as a career. Nursing Research, 17(6), 533–538.

Vondracek, F. W. (1991). Current status of the concept of vocational identity. Man and Work, 3(1–2), 70–86.

Vondracek, F. W. (1992). The construct of identity and its use in career theory and research. The Career Development Quarterly, 41(2), 130–144.

Vondracek, F. W. (1995). Vocational identity across the life-span: A developmental-contextual perspective on achieving self-realization through vocational careers. Man and Work, 6(1), 85–93.

Vondracek, F. W., & Skorikov, V. B. (1997). Leisure, school, and work activity preferences and their role in vocational identity development. The Career Development Quarterly, 45(4), 322–340.

Waterman, A. S., & Waterman, C. K. (1976). Factors related to vocational identity after extensive work experience. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(3), 336–340.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chávez, R. Psychosocial Development Factors Associated with Occupational and Vocational Identity Between Infancy and Adolescence. Adolescent Res Rev 1, 307–327 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0027-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0027-y