Abstract

The purpose of our article is to contemplate, from an aesthetic-artistic vision, the principles of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, adopted by UNESCO in 2005. As a result of a restful, attentive and calm look (contemplation), we believe that the development of a line of thought capable of proposing answers to the great questions posed by the current existential and historical paradigm shift requires an effort of transdisciplinary dialogue. On the one hand, reason, as a specific and differential faculty of the human being, must overcome the limits of its reduction to mere empirical scientism and redefine itself as a reason with an open horizon. On the other hand, the creation of works of art and the aesthetic experience constitutes a way of understanding the complexity and multiplicity of reality. Based on two classic works of art: "The kidnapping of the Sabinas" (Da Cortona) and "Liberty leading the people" (Delacroix) we propose a bio-aesthetic experience on the two fundamental axes on which the principles of the Declaration of UNESCO navigate, which are the centrality of the person and of society. Knowing and deepening such principles, through bio-aesthetic contemplation, is shown as a valid educational instrument, which entails the art of stimulating the capacity to reverberate the beauty existing in the world when good is manifested in human behavior and recognizing the transforming power of art, which facilitates a pedagogical and comprehensive assimilation of the principles of the UNESCO Declaration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Notes

When these exhibitions were made, the main purpose was to become tangible manifestations of specific actions in the field of bio-aesthetics, through the celebration of international cultural events. Cf. http://www.bioethicsart.org/

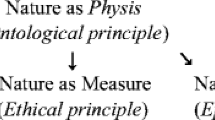

Several philosophers share the same way of thinking: “there is no ethical conduct standing on its own feet. Ethics needs to be grounded upon strong anthropological foundations; that is, on a clear-cut idea of what we are as a species and where we are heading” (Postigo Solana 2021, p. 77).

“Humankind is, no doubt, an animal and an individual, but not like any other. Humankind is an individual guided by itself through intelligence and will. It does not only exist physically, there is a richer and higher being in itself, a spiritual over-existence in knowledge and love” (Maritain 1977, p. 4).

“…the vocation of each person to the perfection of its natures, to the peak of its being, is a super-personal, unique path… Choosing the good is, therefore, a subjective, highly personal decision that, although it does affect the rest of reality, and will eventually benefit or harm more or less other people, it has, above all, an ontological transcendence on the actor, on every actor or moral person that each of us is” (Abellán Salort 2021, pp. 96–97).

The unstoppable exaltation of welfare has annulled the strength given to normative principles, and the ethical action is at risk to become a mere production of spectacle. Cf. Lipovestky G., El crepúsculo del deber. La ética indolora de los nuevos tiempos democráticos. Barcelona 2006; Michaud, Y., El arte en estado gaseoso. FCE. México 2007.

The postulates of what is known as strong transhumanism are perhaps the ones that reveal this tendency most clearly: “the religious-scientific mission implied by the belief in transhumanism leads to the conviction that human beings will be able to transcend their condition as a species in order to concentrate all the fragments of their consciousness in a total cosmic self-awareness that gives fullness to the universal and unique substance of which everything is a part” (Ferrando 2020, p. 85).

Bioethics has as an end the multidisciplinary study between experimental sciences and humanities, trying to establish ethical basis: “bioethics has as its aim the rational analysis of moral problems related to biomedicine and its link with the law field and the human sciences field. This aim implies the elaboration of ethical guidelines based on the values of people and human rights, respecting all religious denominations, with a rational and scientifically appropriate methodological foundation” (Sgreccia 1996, p. 37).

Cfr. Malo 1999, p. 112.

11 “That empirical sciences can fully explain life, the interweaving of all creatures and the whole of reality. That would be to go unduly beyond their limited methodological confines. If one thinks within such a closed framework, aesthetic sensibility, poetry and even the ability of reason to perceive the meaning and purpose of things disappear” (Francis, Laudato si: nº 199).

“The idea of the contemplative spectator means a self-absorption process in which harmony, ecstasy and silence become ideals to achieve aesthetic emotion. With contemplative self-absorption it is possible to ‘physically’ touch the paint, to get inside its universes. Such is the idea that Diderot supports about contemplation. In his writing for the 1765 Salon, he describes the catharsis he felt when he was gazing at the painting Pastorale russe of Jean Baptiste le Prince… it can be found again in Diderot in his commentary for the 1767 Salon regarding to the still lives of Chardin” (Fajardo 2009, p. 43).

Cf. Lipovetsky 2007.

“Noli foras ire, in te ipsum redi, in interiore homine habitat veritas” (San Agustín ‘De vera religione’ (n.d.), XXXIX, 72).

“Contemplation does not have the immobility that is often attributed to it. Rather than the negation of movement, we should speak of its culmination” (Pareyson 1988, p. 24).

Understood as penetration into the contemplated reality. Intuition merges with sensitive perception, understanding and feeling, in the same act.

The allusion to the sense of sight is based on the empirical fact that at least 80% of the information about reality that our brains receive is obtained through it. The intellectual activity, which defines the human being, manages all the complex processes of production and management of knowledge from the data of reality. “Humankind does not possess a faculty of knowledge separated from reasoning. But the reasoning itself is called intelligence. That is to say, the principle of simple, absolute, non-discursive knowledge, insofar as it participates in the simplicity of intuitive intelligence, the principle and end of its own operation” (Aquinas ‘De veritate’: q. 15 a. 1).

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle initiates the conviction that access to knowledge of reality comes through experience and wonder. This is later taken up by the great tradition of Western thought. But “can the humankind of the twenty-first century be amazed or even astonished? We live in the age of science and we think we know almost everything, or at least that we can know everything. And yet, there are and always will be human beings capable of wonder. Amazement is essential to the human condition” (Hersch 2010, p. 7). Some other authors share this opinión, such as (Carson 2012); (De Waal 2007).

“Tempering is to adjust one thing to another”. This concept manifests a particular moment of human apprehension in which sentient intelligence is tempered to the real.

This document is not, as it is specifically stated, an authorised interpretation of the draft of the declaration and its aim is to facilitate discussion and to provide information to clarify the object and purpose of the declaration by facilitating a better understanding of the scope of its provisions.

On the repercussion that the declaration may have on global bioethics refer to (Miranda 2007, pp. 77–79). On the background and with testimonies of many of the participants in the drafting process refer to Ten Have and Jean 2009b. From a critical view on the impact and development of global bioethics in national analysing the evolution, cultural meanings and social role of bioethics, questioning the socio-cultural factors and contingent ideologies that are shaping “bioethics” in different countries or where others promote or undermine the bioethical enterprise and the stated goals of social justice.

“La vida digna y en igual dignidad son el fundamento, la piedra angular, de los deberes y derechos” (Zaragoza 2015, p. 51).

Preamble of United Nations (UDHR) ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’.

Preamble of UNESCO (UDBHR) ‘Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights’ (UNESCO 2005c).

Preamble of the UDBHR, 12th paragraph.

“The principles express the different obligations and responsibilities of the moral subject (‘moral agent’) in relation to different categories of moral objects (‘moral patients’). The principles are arranged according to a gradual widening of the range of moral objects: the individual human being itself (human dignity; benefit and harm; autonomy), other human beings (consent; privacy; equality), human communities (respect for cultural diversity), humankind as a whole (solidarity; social responsibility; sharing of benefits) and all living beings and their environment (protecting future generations and protection of the environment, the biosphere and biodiversity). Some of the principles are already widely accepted (e.g., autonomy; consent). Others have been endorsed in previous declarations (e.g., sharing of benefits). What is innovative in the set of principles listed in the new declaration is the balance struck between individualist and communitarian moral perspectives” (Ten Have and Jean 2009a, pp. 39–40).

Non-published material.

Preamble of the UDBHR, 12th paragraph.

Preamble of the UDBHR, 19th paragraph.

“Seeking to foster integration and exchange is a strategy for working in the perspective of the integral human ecology proposed by Pope Francis, in continuity with the Social Doctrine of the Church. This perspective appeals to a moral and spiritual crisis of global scope where everyone is equally called upon as a human being, guardian of himself and the other. Intensifying, then, interaction is a way to nourish another critical theme, which is the correlation between aesthetics and ethics; that is, how morally beautiful behavior is a vehicle for change. The transformative power of “moral beauty” – underestimated in Western culture, for example, if compared to Eastern culture – is a means to raise awareness of how ethics is a constant in daily life and how it passes through the testimony produced by the actions taken” (García Gómez 2021, p. 8).

References

Abellán Salort, José Carlos. 2021. Los fundamentos ontológicos y éticos de la conexión entre la bioética y la estética. In Bioestética. Reflexiones en torno a la fundamentación, ed. Javier Barraca Mairal, Alberto García Gómez, and Amparo de Jesús Zárate Cuello. Editorial Neogranadina.

Adorno, Roberto. 2021. Prólogo. In Bioestética: Reflexiones en torno a la fundamentación, ed. Javier Barraca Mairal, Alberto García Gómez, and Amparo de Jesús Zárate Cuello. Editorial Neogranadina.

Bagheri, Alireza, Jonathan D. Moreno, and Stefano Semplici. 2015. Global Bioethics: The Impact of the UNESCO International Bioethics Committee. Springer.

Barraca Mairal, Javier, and José Carlos Abellán Salort, eds. 2020. Bioestética y salud humana, 1st ed. Editorial Universidad Francisco de Vitoria.

Barraca Mairal, Javier, and Alberto García Gómez, eds. 2022. Bioestética en tiempos de Coronavirus, 1st ed. Editorial Universidad Francisco de Vitoria.

Barraca Mairal, Javier, Alberto García Gómez, and Amparo de Jesús Zárate Cuello, eds. 2021. Bioestética: reflexiones en torno a la fundamentación. Editorial Neogranadina.

Bovassi, Giulia. 2022. Kairos: el tiempo oportuno del cuidado como posibilidad para rehabilitar la belleza. In Bioestetica en tiempo de Coronavirus, vol. 71, 1st ed., ed. Javier Barraca Mairal and Alberto García Gómez. Editorial Universidad Francisco de Vitoria.

Capánaga, Vicotorino. 1956. San Agustín en nuestro tiempo: La interioridad agustiniana. Augustinus 1. Philosophy Documentation Center: 201–213. https://doi.org/10.5840/augustinus19561214.

Carson, Rachel. 2012. El sentido del asombro. Ediciones Encuentro, S.A.

Chaulagain, Yashoda. 2018. Visual Position and Juxtaposition: An Analytical Study of Liberty Leading the People and Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle. Tribhuvan University Journal 32: 194. https://doi.org/10.3126/tuj.v32i2.24715.

Congregación para la Doctrina de la Fe. 2018. Oeconomicae et pecuniariae quaestiones.- Consideraciones para un discernimiento ético sobre algunos aspectos del actual sistema económico y financiero. Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

De Waal, Esther. 2007. Invitación al asombro: el arte de la mirada espiritual, 1st ed. Ediciones Sígueme.

Di Fino, Giulia. 2022. Riflessioni sulle due opere persona e società.

Reference to the notes

Dicasterio para el Servicio del Desarrollo Humano Integral. 2018. La vocación del líder empresarial. Ed. Dicasterio para el Servicio del Desarrollo Humano Integral and John A. Ryan Institute for Catholic Social Thought of the Center for Catholic Studies. Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Eco, Umberto. 2016. Historia de la belleza / History of Beauty. Debolsillo.

Eguiarte Bendímez, Enrique. 2016. San Agustín y la interioridad. Preámbulos y dos textos de los “Diálogos de Casiciaco.” Recollectio: Annuarium Historicum Augustinianum: 105–132.

Eisenman, Stephen F. 2020. Nineteenth century art: A critical history, 5th ed. Thames & Hudson.

Fajardo, Carlos. 2009. De la contemplación estética a la interacción participativa. Enunciación 14: 42–50. https://doi.org/10.14483/22486798.3091. (District University of Bogotá).

Ferrando, Rafael Monterde. 2020. Julian Huxley’s transhumanism: A new religion for humanity. Cuadernos de Bioetica : Revista Oficial de La Asociacion Espanola de Bioetica y Etica Medica 31: 71–85.

Forest, Aimé. 1943. Consentement et création. Aubier.

García Gómez, Alberto. 2021. Fostering the art of convergence in global bioethics. International Journal of Ethics Education 6: 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-020-00117-9

García Gómez, Alberto, and Giulia Bovassi. 2020. Le sfide delle tecnologie emergenti alla luce dei diritti umani per una bioetica globale. In Bioetica tra passato e futuro: Da Van Potter alla società 5.0, ed. Enrico Larghero and Mariella Lombardi Ricci, 213–242. Effatà Editrice.

Han, Byung-Chul. 2022. La Sociedad del Cansancio. Herder & Herder.

Heinich, Nathalie. 2017. El paradigma del arte contemporáneo: estructuras de una revolución artística, 1st ed. Casimiro Libros.

Hersch, Jeanne. 2010. El gran asombro: La curiosidad como estímulo en la historia de la filosofía, 1st ed. El Acantilado.

Jiménez, José, ed. 1998. El nuevo espectador. Fundacion Argentaria: Visor.

Jiménez, José. 2002. Teoría del arte. Tecnos Editorial S A.

Kleiner, Fred S. 2015. Gardner’s art through the ages: A global history, Volume II. Cengage Learning.

Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2007. La felicidad paradójica: Ensayo sobre la sociedad de hiperconsumo. Editorial Anagrama.

Lipovetsky, Gilles, and Jean Serroy. 2015. La estetización del mundo: vivir en la época del capitalismo artístico, 3rd ed. Editorial Anagrama.

Lopes, Dominic McIver. 2018. Aesthetics on the edge: Where philosophy meets the human sciences. Oxford University Press.

Maioni, Melissa. 2022. El arte oblativo y la profesión médica. La fascinación del ‘amor hermoso’ en la era de la pandemia. In Bioestética en tiempos de Coronavirus, 1st ed., ed. Javier BarracaMairal and Alberto García Gómez. Editorial Universidad Francisco de Vitoria.

Malo, Antonio. 1999. El sentimiento en la Noología de Zubiri. Acta Philosophica: Rivista Internazionale di Filosofia 8: 111–117.

Maritain, Jacques. 1977. I diritti dell’uomo e la legge naturale. Vita e Pensiero: 114

Michaud, Yves. 2007. El arte en estado gaseoso: Ensayo sobre el triunfo de la estetica. Fondo de Cultura Economica USA.

Miranda, Gonzalo. 2007. La Dichiarazione Universale sulla Bioetica e i Diritti Umani dell’UNESCO. Il percorso politico-diplomatico. In La globalizzazione della bioetica. Un commento alla Dichiarazione Universale sulla bioetica e i diritti umani dell’UNESCO, ed. Fabrizio Turoldo, 77–79. Gregoriana Libreria Editrice.

Muñoz López, Blanca. 1995. Ilustración y educación estética: el debate entre Modernidad y Post-Modernidad. Kobie. Bellas Artes: 199–216.

Olin, Martin. 2017. A Drawing for Pietro da Cortona’s Rape of the Sabine Women. Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm 24–25: 27–30.

Paglia, Vincenzo Archbishop. 2018. Challenges of the culture of life. https://www.academyforlife.va/content/pav/en/the-academy/the-president/speeches---2018/archbishop-paglia-in-mexico---march-13th-18th-2018.html. March 14.

Pareyson, Luigi. 1988. Conversaciones de estética. Visor.

Pedrajas, Marta. 2017. La Última Milla: Los desafíos éticos de la pobreza extrema y la vulnerabilidad en la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible de Naciones Unidas. Veritas: Revista De Filosofía Y Teología: 79–96. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-92732017000200079

Plazaola, Juan. 1999. Introducción a la estética: Historia, Teoría, Textos, 3rd ed. Universidad de Deusto.

Postigo Solana, Elena. 2021. Toward the abolition of the idea of human nature and the ushering in of another “Advent of a new man.” In Enhancement fit for humanity: perspectives on emerging technologies, 1st ed., ed. Michael Baggot, Alberto García Gómez, Alberto Carrara, and Joseph Tham, 72–85. Routledge.

Quiles, Ismael. 1989. La interioridad agustiniana. Buenos Aires: Depalma.

San Agustín. De Magistro (El maestro). (n.d.). https://www.augustinus.it/spagnolo

San Agustín. De vera religione (De la verdadera religión). (n.d.). https://www.augustinus.it/latino

San Agustín. Confessiones (Las Confesiones). (n.d.). https://www.augustinus.it/spagnolo

San Agustín. De ordine (El Orden). (n.d.). https://www.augustinus.it/spagnolo

Sánchez De Muniain Y Gil, José María. 1978. Principios de estética general. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Sgreccia, Elio. 1996. Manual de bioética. Diana.

Sutherland Harris, Ann. 2008. Seventeenth-century art & architecture, 2nd ed. Prentice Hall.

Ten Have, Henk. 2015. Bioethics education in a global perspective: Challenges in global bioethics. Springer.

Ten Have, Henk. 2016. Global bioethics: An introduction. Routledge.

Ten Have, Henk, and Bert Gordijn, eds. 2013. Handbook of global bioethics, 1st ed. Springer.

Ten Have, Henk, and Michèle Jean. 2009a. Introduction. In The UNESCO Universal declaration on bioethics and human rights: Background, principles and application, 17–55. UNESCO Publishing.

Ten Have, Henk, and Michèle S. Jean, eds. 2009b. The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, principles and application. UNESCO Publishing.

TomasiVelli, Silvia. 1991. L’iconografia del “Ratto delle Sabine”. Un’indagine storica. Prospettiva 63: 17–39.

UNESCO. 1997. Declaración Universal sobre el Genoma Humano y los Derechos Humanos. https://es.unesco.org/about-us/legal-affairs/declaracion-universal-genoma-humano-y-derechos-humanos. November 11.

UNESCO. 2001. Records of the general conference, 31st session, vol. 1: Resolutions. 31 C/Resolutions. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000124687. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO. 2003. Report by the Director-General on the possibility of elaborating universal norms on bioethics. 32 C/59. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000131636

UNESCO. 2005a. Explanatory memorandum on the elaboration of the preliminary draft Declaration on Universal Norms on Bioethics. SHS.2005/CONF.203/CLD.4, SHS/EST/05/CONF.203/4. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000139024. Division of Ethics of Science and Technology.

UNESCO. 2005b. Explanatory memorandum on the elaboration of the preliminary draft Declaration on Universal Norms on Bioethics. SHS.2005/CONF.204/CLD.2, SHS/EST/05/CONF.204/4. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000139586. Division of Ethics of Science and Technology.

UNESCO. 2005c. Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UDBHR). https://en.unesco.org/about-us/legal-affairs/universal-declaration-bioethics-and-human-rights

UNESCO. 2011. Bioethics core curriculum, section 2: Study materials; Ethics Education Programme. SHS/EST/EEP/2011/PI/3. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000210933. Sector for Social and Human Sciences, Division of Ethics of Science and Technology.

United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights. December 10.

Zaragoza, Federico Mayor. 2015. La dignidad como fundamento de todos los derechos humanos. In ¿Por qué una Bioética Global? 20° aniversario del Programa de Bioética de la UNESCO, ed. Germán Solinís, 51–56. UNESCO Publishing.

Zubiri, Xavier. 1993. Sobre el sentimiento y la volición. Alianza Editorial Sa.

Zunzunegui, Santos. 2003. Metamorfosis de la mirada: museo y semiótica. Ediciones Cátedra. Universitat de València.

Acknowledgements

Original Spanish text translated into English by María Martín Verdugo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies involving animals performed by any of the authors.

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interests/competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bueno Pimenta, F.J., García Gómez, A. Contemplating the principles of the UNESCO declaration on bioethics and human rights: a bioaesthetic experience. International Journal of Ethics Education 8, 249–274 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-023-00176-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-023-00176-8