Abstract

This study quantifies the social welfare loss caused by market power in Peru’s regulated microfinance industry and analyzes its effect on microfinance institutions’ (MFIs) efficiency from 2003 to 2019. We estimate the efficiency-adjusted Lerner index as a measure of market power and obtain efficiency scores via cost and profit stochastic frontiers estimation using data from a wide panel of MFIs. Additionally, to analyze the effect of market power on the MFI’s efficiency, we estimate a fixed effects model with instrumental variables to correct the endogeneity problem. The results show that the welfare loss due to market power in Peru’s regulated microfinance industry has increased from 0.12% of GDP in 2003 to 0.27% in 2019. It is also found that market power positively affects Peruvian MFIs’ efficiency. Therefore, reducing market power leads to a welfare gain by lowering the social welfare loss (Harberger’s triangle) and a welfare loss due to decreased efficiency in MFIs. However, we find that reducing market power leads to a positive net effect on social welfare due to greater welfare gain than loss.

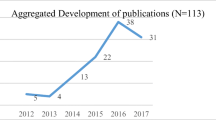

Source: SBS. Own elaboration

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Notes

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) with microcredit programs and cooperatives specialized in microfinance are also part of the Peruvian microfinance system. The most important of these entities voluntarily report their financial information to the MIX Market database. According to this information, these institutions were responsible for 6% of the total microloans placed by the Peruvian microfinance system in 2019. Given their reduced participation in the national microcredit supply, our analysis only considers regulated MFIs.

See the Appendix for this demonstration.

For a presentation of this literature, see the paper by Fall et al. (2018).

Resolution SBS 1276–2002, which approved the regulations for the entry of MFIs into the Lima market.

Superintendencia de Bancos, Seguros y Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones (SBS) (2003).

Legislative Decree 1028/2008, which amends Article 290 of Law 28677, General Law on the Financial System and the Insurance System and Organic Law on the Superintendency of Banking, Insurance, and Private Pension Funds Administrators.

It should be noted that we estimate an alternative profit frontier that, unlike the standard one, takes into account that financial intermediation institutions (in this case, MFIs) do not act in a perfectly competitive market, and therefore, the price of their product it is not given; if not, they can establish it by fixing their output. Consequently, we include output and input prices as exogenous variables in the profit frontier (Berger & Mester, 1997; Humphrey & Pulley, 1997). Under this assumption, we use profits as an endogenous variable and the same explanatory variables as in the cost frontier case.

For a detailed presentation on stochastic frontiers, see Kumbhakar and Lovell (2003).

We follow the intermediation approach of Benston et al. (1982), which defines financial intermediaries as firms that produce loans from the combination of the following inputs: loanable funds, labor, and physical infrastructure. This approach defines the cost concept broadly because it includes financial and operating costs within the total cost. In addition, in the particular case of MFIs, given that they finance volatile economic activities, their loan portfolios are exposed to greater credit risk, which implies the constitution of high provisions for expected losses for the entity. Although provisions are not an outflow of resources, they reduce the entities’ capital in accounting terms, constituting a cost for them, so the credit risk cost must be considered part of the total cost. Finally, we measure production as the monetary value of total loans.

In the case of negative profits, we use the following estimation: \({TP}_{AD}=(profits) (PROFIT\_EFFI)\).

See Sect. 2 for details.

Our results are robust with different specification of lags. We use clustered standard errors.

See Table 10: First stage of IV with fixed effects estimation.

The exclusion restriction is difficult to test. The direct influence of these instruments (LIAD,t−7, LIAD,t−8, LIAD,t−9, LIAD,t−10, LIAD,t−11, LIAD,t−12) on contemporary efficiency (EFFIt) is unlike because market power from 7 months ago or even further back cannot influence EFFIt or its influence would be negligible. In any case, the influence of these instruments would be indirect through contemporary market power (LIAD,t).

At the outset, we had data for 44 MFIs: thirteen CMACs, two banks specializing in microfinance, thirteen CRACs, and fourteen EDPYMEs. However, it was decided to exclude those entities that were taken over at an early stage, as they provided only a small number of observations and represented less than 3% of total loans in the Peruvian microfinance market. This left a panel of 37 MFIs.

For the Mexican banking sector, Solís and Maudos (2008) detected a social welfare loss representing, on average, 0.34% of GDP from 1993–2005. In the study by Maudos and Fernández de Guevara (2007) on 15 EU banks from 1993–2002, the average welfare loss was 0.49% of GDP for this group of countries. Although these values are not comparable with those we estimate for the Peruvian microfinance industry, they are referential for our analysis.

There are no prior estimations of welfare losses caused by cost and profit inefficiency for the microfinance industry. However, Solís and Maudos (2008) presented such estimates for the Mexican banking industry. They reported welfare losses associated with cost and profit inefficiency, as a percentage of GDP, of 0.02% and 0.07%, respectively. Maudos and Fernández de Guevara (2007) found that, for 15 EU countries, the welfare loss associated with cost inefficiency totaled 0.35% of the GDP of this group of European countries.

We use the xtivreg2 command in Stata to estimate the fixed effects model with instrumental variables. See Schaffer (2005) for more details on the command.

See Baum et al. (2007) for more details on these diagnostic tests for the fixed effects model with instrumental variables.

The estimates of this new alternative profit frontier are described in Table 11.

The main regression table is available on request.

References

Aguilar, G., & Portilla, J. (2020). Determinants of market power in the Peruvian regulated microfinance sector. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 20(4), 657–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-019-00318-z

Ariss, R. T. (2010). On the implications of market power in banking: Evidence from developing countries. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(4), 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.09.004

Assefa, E., Hermes, N., & Meesters, A. (2013). Competition and the performance of microfinance institutions. Applied Financial Economics, 23(9), 767–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2012.754541

Baquero, G., Hamadi, M., & Heinen, A. (2018). Competition, loan rates, and information dispersion in nonprofit and for-profit microcredit markets. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 50(5), 893–937.

Bassem, B. S. (2012). Social and financial performance of microfinance institutions: Is there a trade-off? Journal of Economics and International Finance, 4(4), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.5897/JEIF11.129

Baum, C., Schaffer, M., & Stillman, S. (2007). Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. Stata Journal, 7(4), 465–506.

Benston, G., Hanweck, G., & Humphrey, D. (1982). Scale economies in banking: A restructuring and reassessment. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 14(4), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991654

Berger, A. N., & Hannan, T. H. (1998). The efficiency cost of market power in the banking industry: A test of the “quiet life” and related hypotheses. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(3), 454–465.

Berger, A., & Mester, L. (1997). Inside the black box: What explains differences in the efficiencies of financial institutions? Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(7), 895–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(97)00010-1

Cuéllar-Fernández, B., Fuertes-Callén, Y., Serrano-Cinca, C., & Gutiérrez-Nieto, B. (2016). Determinants of margin in microfinance institutions. Applied Economics, 48(4), 300–311.

de Quidt, J., Fetzer, T., & Ghatak, M. (2018). Market structure and borrower welfare in microfinance. The Economic Journal, 128(610), 1019–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12591

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank Publications. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4

Demsetz, H. (1973). Industry structure, market rivalry, and public policy. The Journal of Law and Economics, 16(1), 1–9.

Fall, F., Akim, A., & Wassongma, H. (2018). DEA and SFA research on the efficiency of microfinance institutions: A meta-analysis. World Development, 107, 176–188.

Fernández de Guevara, J., & Maudos, J. (2004). Measuring welfare loss of market power: An application to European banks. Applied Economic Letters, 11, 833–836.

Fu, X., Lin, Y., & Molyneux, P. (2014). Bank competition and financial stability in Asia Pacific. Journal of Banking & Finance, 38, 64–77.

Fuentes-Dávila, H. (2016). Determinantes del margen financiero en el sector microfinanciero: El caso peruano. Revista Estudios Económicos, 32, 71–80.

Greene, W. (2005). Fixed and random effects in stochastic frontier models. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 23(1), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-004-8545-1

Gregoire, J. R., & Tuya, O. R. (2006). Cost efficiency of microfinance institutions in Peru: A stochastic frontier approach. Latin American Business Review, 7(2), 41–70.

Guha, B., & Chowdhury, P. R. (2013). Micro-finance competition: Motivated micro-lenders, double-dipping and default. Journal of Development Economics, 105, 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.07.006

Haghnejad, A., Samadi, S., Nasrollahi, K., Azarbayjani, K., & Kazemi, I. (2020). Market power and efficiency in the Iranian banking industry. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(13), 3217–3234. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1643716

Halouani, N., & Boujelbène, Y. (2015). External Governance and Dual Mission in the African MFIs. Strategic Change, 24(3), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2007

Haq, M., Skully, M., & Pathan, S. (2010). Efficiency of microfinance institutions: A data envelopment analysis. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets, 17(1), 63–97.

Harberger, A. (1954). Monopoly and resource allocation. The American Economic Review, 44(2), 77–87.

Hermes, N., & Hudon, A. (2018). Determinants of the performance of microfinance institutions: A systematic review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(5), 1483–1513. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12290

Hermes, N., Lensink, R., & Meesters, A. (2011). Outreach and efficiency of microfinance institutions. World Development, 39(6), 938–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.10.018

Hermes, N., Lensink, R., & Meesters, A. (2018). Financial development and the efficiency of microfinance institutions. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hicks, J. R. (1935). Annual survey of economic theory: The theory of monopoly. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 3, 1–20.

Hossain, S., Galbreath, J., Hasan, M. M., & Randøy, T. (2020). Does competition enhance the double-bottom-line performance of microfinance institutions? Journal of Banking & Finance, 113, 105765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2020.105765

Humphrey, D., & Pulley, L. (1997). Banks’ responses to deregulation: Profits, technology, and efficiency. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/2953687

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI]. (2022a). Evolución de la Pobreza Monetaria 2010–2021. Informe Técnico.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI]. (2022b). Producción y Empleo Informal en el Perú - Cuenta Satélite de la Economía Informal 2007–2021.

Koetter, M., Kolari, J. W., & Spierdijk, L. (2012). Enjoying the quiet life under deregulation? Evidence from adjusted Lerner indices for US banks. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(2), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00155

Kumbhakar, S., & Lovell, C. (2003). Stochastic frontier analysis. Cambridge University Press.

León, J. V. (2009). An empirical analysis of Peruvian municipal banks using cost-efficiency frontier approaches. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 29(1–2), 161–182.

Lerner, A. (1934). The concept of monopoly and the measurement of monopoly power. Review of Economic Studies, 1(3), 157–175.

Marconi, R., & Mosley, P. (2006). Bolivia during the global crisis 1998–2004: Towards a macroeconomics of microfinance. Journal of International Development, 18(2), 237–261.

Marquez, R. (2002). Competition, adverse selection, and information dispersion in the banking industry. The Review of Financial Studies, 15(3), 901–926. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/15.3.901

Maudos, J., & Fernández de Guevara, J. (2007). The cost of market power in banking: Social welfare loss vs. cost inefficiency. Journal of Banking & Finance, 31, 2103–2125.

Mayorca, E., & Aguilar, G. (2016). Competencia y calidad de cartera en el mercado microfinanciero peruano, 2003–2015. Economía, 39(78), 67–93.

McIntosh, C., De Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2005). How rising competition among microfinance institutions affects incumbent lenders. The Economic Journal, 115(506), 987–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2005.01028.x

McIntosh, C., & Wydick, B. (2005). Competition and microfinance. Journal of Development Economics, 78(2), 271–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.11.008

Mia, M. A. (2022). Social Purpose, Commercialization, and Innovations in Microfinance. Springer Books. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0217-8

Motta, M. (2004). Competition policy: Theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Nguyen, T., Nghiem, H., Roca, E., & Sharma, P. (2016). Efficiency, innovation and competition: Evidence from Vietnam. China and India. Empirical Economics, 51(3), 1235–1259.

Oroz, M., & Salas, V. (2003). Competencia y eficiencia en la intermediación financiera en España, 1977–2000. Moneda y Crédito, 217, 73–99.

Quayes, S., & Khalily, M. B. (2013). Efficiency of microfinance institutions in Bangladesh. Institute of Microfinance.

Restrepo-Tobón, D., & Kumbhakar, S. (2014). Enjoying the quiet life under deregulation? Not quite. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 29(2), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.2374

Riaz, M., & Gopal, P. (2015). In competency aspects of microfinance industry: Via SFA approach. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 7(1(J)), 1–12.

Schaffer, M. (2005). XTIVREG2: Stata module to perform extended IV/2SLS, GMM and AC/HAC, LIML and k-class regression for panel data models. Statistical Software Components S456501. Boston College Department of Economics.

Solis, L., & Maudos, J. (2008). The social costs of bank market power: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Comparative Economics, 36, 467–488.

Stock, J., & Yogo, M. (2005). Asymptotic distributions of instrumental variables statistics with many instruments. Identification and Inference for Econometric Models: Essays in Honor of Thomas Rothenberg, 6, 109–120.

Superintendencia Bancos de Seguros y Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones (SBS). (2003). Memoria anual 2002. Superintendencia de Bancos. Seguros y Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones.

Tadesse, G., Borzaga, C., & Getnet, K. (2014). Cost-efficiency and outreach of microfinance institutions: Trade-offs and the role of ownership. Journal of International Development, 26(6), 923–932.

Vogelgesang, U. (2003). Microfinance in times of crisis: The effects of competition, rising indebtedness, and economic crisis on repayment behavior. World Development, 31(12), 2085–2114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.09.004

Watkins, T. (2018). Introduction to Microfinance. World Scientific Press.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú to carry out this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Material preparation and data collection were performed by JP and analysis by GA and JP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by both authors. Also, both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

We have consented for the publication of this research in this journal.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

-

1.

Harberger’s triangle

An MFI with market power in the microcredit market maximizes its profit by choosing the price or interest rate (P) that it will charge for its loans (L). The problem to be solved is therefore:

The first-order condition to solve this problem is:

Since \(\frac{\partial TC }{\partial L}\) is the marginal cost (MC), the term on the left of Eq. (13) is the Lerner index (LI) and \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P}\frac{P}{L}\) is the price elasticity of loans demand (ɛ). Therefore, we obtain from profit maximization:

The net loss of social welfare in Fig. 1 is equivalent to the area of triangle ABC:

Replacing ɛ from Eq. (14), we have:

Replacing LI by \(\frac{{P}^{*}\left(L\right)-MC}{{P}^{*}}\), we have:

See Table 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Aguilar, G., Portilla, J. Market power, social welfare, and efficiency in the Peruvian microfinance. Econ Polit 41, 123–152 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-023-00321-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-023-00321-y