Abstract

This study evaluates whether a gender bias exists in the reelection of regional councilors in Italy. A dataset of 4794 councilors elected since 1985 is considered; 597 (i.e., 12.45%) among them are women. The determinants of the reelection are analyzed. A significant gender bias in reelection emerges, even after controlling for several individual and institutional factors. The gender bias in reelection is stable over time, similar across different traditional political parties, and similar in different geographical areas. Institutional and individual factors are also studied in the interaction with gender bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Gender imbalances characterize many fields all over the world, spanning economy, society, culture and science,Footnote 1 notably reflected in political representation. A large body of literature proves that significant gender biases exist in the election of parliament and local public councils, in many –perhaps, in most– countries.Footnote 2

The present study evaluates whether a gender bias exists in the reelection process, taking the regional councilors in Italy as the case study.Footnote 3 Specifically, we consider here the dataset of 4,794 councilors, elected in all Italian regions from 1985 to 2020. Only 597 (12.45%) of these councilors are women; of course, this evidence preliminarily suggests that a gender bias does exist in the election process. However, we do not investigate here the bias in the probability of being elected, but the determinants of the reelection. Our dataset shows that only 36.0% of female councilors gain at least one reelection, compared to the 46.6% among male councilors.

The focus on reelection is a novelty of the present analysis with respect to most of the prior literature. Of course, reelection per se can be seen as a good or a bad aspect of democracy: on the one side, reelection can be considered as a reward for a good job in the previous term; on the other side, the persistence in office could be a sign of scarce competition (Baltrunaite et al., 2014; Besley, 2005). We here simply evaluate whether a gender bias against women in reelection exists.

There are at least two reasons why gender bias in reelection is worth investigation. First, it is interesting to evaluate whether gender bias continues to be operative even after a first election has been obtained, that is, even after previous hurdles have been overcome. Second, available research shows that the presence of women in political councils –especially in government bodies– is effective in driving public choices, and notably the choice concerning public goods to be supplied.Footnote 4 Hence, the continuity of women’s presence in councils is a relevant point for assuring the effectiveness of women-driven policy decisions.

Our present investigation documents that a gender bias exists, even after the first election into a regional council: being a woman in itself entails a negative and significant effect, even after controlling for a set of other individual and institutional features. The gender bias in reelection appears to be pretty stable over time, even if the number of elected women has been increasing over time. Under this perspective, one could conclude that the gender bias in reelection is more stable, and harder to diminish, than the gender bias in entering political councils. The gender bias emerges to be similar across different traditional political parties, and similar across different geographical areas. Evidence on a sub-sample of councilors for whom information on re-candidacy is available suggests that the gender bias is present in both the stage of the candidate lists formation and the stage of vote.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a short review of the relevant literature. Section 3 provides a description of the institutional context of the present study, concerning regional councilors in Italy; it is worth underlining that the regional councils in Italy are more similar to the national Parliament than to municipal councils, in terms of prestige, power, and also remuneration of councilors. Section 4 describes the dataset and provides some statistical evidence.Footnote 5 Section 5 presents a preliminary econometric analysis on the general probability of reelection for regional councilors in Italy. A gender bias clearly emerges from the results presented in Sects. 4 and 5. Section 6 is devoted to a specific analysis of the features of the gender bias in councilors’ reelection. Section 7 deals with possible gender bias in re-candidacies. Section 8 evaluates whether a gender bias exists for regional councilors who are elected to the national (or European) Parliament. Section 9 concludes.

2 Related literature

The gender gap is a multifaceted socioeconomic phenomenon. Since 2006, four dimensions of the gender gap have been tracked in the Global Gender Gap Index provided by the World Economic Forum (WEF 2021): health, education, economic opportunities, and political leadership. The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 observes that political leadership is the dimension that registers the slowest pace toward parity. Nowadays, globally, women are almost as educated as men, but they do not have the same opportunities to enter the job market and, above all, the political arena.

A wide body of socioeconomic literature analyzes the reasons for the underrepresentation of women in different layers of government. The reasons for this underrepresentation in political offices can arise in different stages of the electoral process: the selection of candidates and the composition of the lists; the electoral race, according to the rules on which it is based; and the possible reelection of incumbents.

In the selection process, women must overcome the skepticism of the political parties, which do not encourage them to run, and the lack of self-confidence, both of which are due to gender stereotypes characterizing social norms (Fox and Lawless, 2004, 2011). The first obstacle to gender parity in political competition is the scarcity of women in the eligibility pool from which candidates are chosen, and in the candidate list.

To remove this obstacle, since the 1990s, gender quotas have been introduced –as a matter of law in electoral systems or voluntarily by political parties– to ensure a minimum number of women in candidate lists. The Inter-Parliamentary Union Report considers quotas as a key determinant for increasing women’s political participation across the world (IPU 2021). The quota system is obviously more binding when the legislation states the reservation of both candidacies in the party’s list and seats in the elective assemblies.Footnote 6 Less binding quota systems, which consist only of quotas in candidacies, have been spread in Europe, mainly in local elections, since the 1990s (EP-DG-Ipol 2011).Footnote 7 Several studies have been conducted to empirically verify the effectiveness of gender quota systems. As far as Italy is concerned, De Paola et al., (2010, 2014) find a long-lasting positive effect of the gender quotas, even if the magnitude of this effect is not very large, along with a higher voter turnout. Baltrunaite et al., (2014, 2019) find that the quality of politicians (both men and women) was persistently higher after the first introduction of a quota system in Italy.

The impact of the electoral rules (majoritarian vs. proportional system) on female representatives is largely investigated by the available literature. Generally, proportional electoral systems seem to better protect female candidates from voters’ bias against women than do majoritarian electoral systems (Kittilson & Schwindt-Bayer, 2010; Norris, 2006; Rule, 1994). Some studies deepen the analysis by estimating the impact of different proportional systems (closed list, open list, etc.). The findings are mixed: for example, Jones and Navia (1999) argue that closed lists enhance the probability for women to be elected in Chilean municipal elections; Golder et al. (2017), in an experimental study conducted during the European Parliament election in 2014, show that open lists with panachageFootnote 8 would have the most favorable impact on women elected in public bodies. The study of Profeta and Woodhouse (2018) on the impact of the Italian electoral reform in 2005, reintroducing a proportional system with closed lists for the national election, confirms the positive role of a proportional system with closed lists on female representatives. However, the results show that women elected in the Italian Parliament after the 2005 reform are less educated and have less previous political experience than men elected; and a higher turnover rate is registered among women (Profeta & Woodhouse, 2018, pp. 15–16).

The evidence from the available literature leads to a radical question on the real effectiveness of the electoral reforms devoted to promoting female representatives in elective bodies: do political parties really change their mind on the role that women can play in politics, or do they just comply with the new rules, and select women candidates not according to their competencies but just according to gender? The fact that political parties just want to comply with the law could explain the higher turnover among women than men. Women are inserted in the electoral list because political parties must do that, but women do not really get a chance to start a political career. In other words, gender quotas could help to increase the presence of women in political offices but do not help to increase the chance for women to start a successful political career.

All the above-mentioned studies focus on gender bias in election. Less interest has been spent by scientific research on reelection. To the best of our knowledge, only few studies provide specific evidence on gender bias in reelection: Brollo and Troiano (2016) show that female majors in Brazil have a lower incumbent advantage than male majors, due to a less strategic behavior performed in their first electoral term.Footnote 9 Profeta and Woodhouse (2018, p. 16) show that women in Italy have fewer chances than men to be reelected for a second consecutive term at all subnational levels of government, and fewer chances to move up from one level of government to another. The study focuses on the role played by the electoral rules at the national level and shows that women have more chances to be reelected under majoritarian electoral rules. Among the determinants of possible gender discrimination in reelection, some factors that usually keep women away from political competition can be taken into account, such as the lack of political ambition, and the opportunity cost of a political career in terms of work-life balance. Other factors may concern the role played by the women elected in previous terms, e.g., the involvement in government bodies of women elected in parliamentary assembly, and, more generally, the opportunity really given to women to show their political and government skills and to accumulate political expertise. As happens in competition for top jobs in the labor market (Bjerk, 2008), women at the beginning of their political career might face hurdles and might not have the same opportunities to show their skills and accumulate political expertise: this “sticky floor” can compromise their future political career (Cipullo, 2021, p. 24).

Our present study is devoted to investigating the reelection process, taking the Italian regions as the case study. We control for the individual characteristics of political councilors, and for institutional factors beyond electoral rules. Under this perspective, our present study complements the body of available literature.

3 The case study of Italian regions: the institutional framework

Italy is articulated into 20 regions, whose sizes are very heterogeneous, in terms of surface, population, economic conditions, and hence regional budget. Table 11 in Appendix provides the list of the Italian regions, with some characteristics.Footnote 10 Five regions, labeled as “Autonomous regions with special statute”, have larger autonomy than the other 15, labeled as “Regions with ordinary statute”.

During the time period under consideration in this study, 1985 to today (2023), some institutional and electoral reforms have taken place. We limit our discussion to those with possible impact on the gender issue under consideration.

In 1995, a national electoral reform for the ordinary-statute regions established that the winning coalition receives an absolute majority of seats in the council, moving the electoral system from a proportional toward a majoritarian paradigm. In subsequent years, similar reforms were also adopted by regions with special autonomy.

In 1999, a significant constitutional reform was adopted, coming into force in 2001. It has revised and enlarged the powers of regions. Currently, regions have legislative power on issues not expressly reserved to state law; among the tasks of regions, health service provision is perhaps the most important one.

Following the 1999 constitutional reform, a national law in 2004 (Law 165/2004) established that each region adopts its regional electoral system, in line with common general principles, including gender balance. As a consequence, since the 2005 elections, different regional electoral systems have been in force. The gender balance issue has also been handled differently across regions, with rules specifying the reservation of candidacies for either sex (quota) and/or rules for the expression of preferences (conditioned double preference). In 2016, a modification of the national law established clear ways to rule the gender balance: in particular, these include at least 40% of candidacies for either sex and mandatory alternate preferences (if multiple preferences on candidates are possible).Footnote 11 It is important to underline that all the measures taken over time, and still in force, in all regions, do not ensure a minimum quota of elected councilors per gender.

In the time period under consideration in this analysis, the number of members of regional councils ranged between 20 and 90, varying both across regions (depending on the regional population) and over time (also due to reforms).Footnote 12 The length of a term, for regional councils, is five years. However, in some cases, the term’s length has been shorter, due to the resignation of the president of the region: if this happens, new elections are called, and a new (five-year) term starts. This is the reason why regions now go to election in different years.

4 Dataset and method

Raw data concerning regional councilors in Italy are freely available from the government website https://dait.interno.gov.it/elezioni/open-data. The site provides the list of councilors in office on December 31st of each year, from 1985 to 2020. Further pieces of personal and institutional information are also provided by the same website, including the date of birth, gender, education, and political party of each councilor. This source is the starting point to build our dataset, which is integrated with information from the websites of the regions, if necessary. In our dataset we do not include the councilors who served for less than one yearFootnote 13; typically, this is the case for councilors entered in office at the end of a term. We believe that it is appropriate to delete them from the dataset because our primary goal is to evaluate the determinants of reelection, for people who have served as councilor for a significant period of time. We also omit individuals who served in the regional government cabinet without being elected or without having previously been elected in the regional council.Footnote 14 Again, we omit those who were elected for the first time in the current regional councils’ term (as evaluated at 31. Dec 2020); this is obvious, since our goal is to evaluate the probability of reelection, and the councilors elected for the first time in the current term have no possibility of reelection. According to these criteria, our sample comprises 4,794 councilors. In fact, this is near the total of the Italian regional councilors elected since 1985. Some of them (2625) served for only one term, or a fraction of one term (in any case, more than one year); the others (2169) made two or more terms, up to as many as nine terms, that is, eight reelections (i.e., the councilor has been in office continuously from 1985 to 2020 in a region where nine elections have taken place).

Table 1 reports some statistics on the regional councilors in dataset. Clear signs of a gender gap emerge. As already noted, the percentage of women in the dataset is very low (12.45%), underscoring the presence of gender bias in the election process. Moreover, the percentage of elected women who have secured at least one reelection is lower than the corresponding percentage for men (about 36% vs. 46%), indicating that the gender bias also affects reelections. The point is consistently supported also by the evidence that the average number of years in office is demonstrably lower for women than men: 6.71 years compared to 7.47 years, and the average number of reelections is lower for women than men (0.50 vs. 0.68). Furthermore, the percentage of elected women who are appointed in the regional cabinet is lower as compared to the corresponding percentage of men (21.4 vs. 27.8%). This lends clear support to the point that female councilors have less occasion to show their governmental skill as compared to males. Among the councilors, women are, on average, younger than men at the date of their first election (43.7 vs. 46.3 years old), and they are more educated (as measured by the percentage of graduated councilors, 60.3% vs. 56.6%). This evidence, in line with results from different case studies (e.g., De Paola et al., 2010), may suggest that women have to overcome higher hurdles and voters' prejudice, as compared to men. Education is one such hurdle; another may be the nearly canonic bias by which women are often judged: that of physical appearance and beauty, more manifest in younger rather than older women compared to men (see also Profeta & Woodhouse, 2018, p. 27).

After the basic statistics analysis, we move to multiple regression analysis, in a cross-section framework, to investigate the determinants of councilors’ reelection and the possible presence of gender bias. In all cases (unless otherwise specified), 4794 observations are considered, corresponding to the regional councilors in the dataset. The number of reelections (a counting variable) and the occurrence of at least one reelection (a dichotomous variable, equal to 0 for councilors who served for only one term or a fraction of one term, and equal to 1 for councilors who have gained at least one reelection) are taken as the dependent variable. Hence, appropriate estimators are the Poisson estimator and the logit estimator, respectively. In the first regression exercise (preliminary regression), we also provide the outcome from OLS models, having the number of reelections and the length of time in office as dependent variables.Footnote 15 We will see that all the results are fully consistent across different estimators. First, regressions in Sect. 5 evaluate whether being a woman exerts an effect on reelection, ceteris paribus. Results unanimously document that the gender bias is present, significant, and robust to the consideration of other determinant factors. Second, regressions in Sect. 6 shed light on how the gender bias interacts with other individual determinants and institutional factors.

5 Preliminary regression analysis

Table 2 provides the results of a preliminary multiple regression equation. Column 1 reports the OLS regression with the number of years in office, for each councilor, as the dependent variable. Column 2 shows the OLS regression with the number of reelections as the dependent variable. Column 3 reports the Poisson estimator, appropriate in the case of counting variable.Footnote 16 Column 4 reports the outcome of the logit model, having the occurrence of a reelection (or not) as the dependent variable.Footnote 17

The explanatory variables under initial consideration may be articulated in three groups: (a) a set of variables capturing regional councilors’ individual characteristics, (b) a set of variables for regional characteristics, and (c) the constant term and the year of first election for each councilor. Specifically:

(a) The individual characteristics of councilors include: age, education level, possible appointment as a member of the regional government, and gender (a dummy variable with the value of 1 for female).

The effect of age, at the time of the first election, turns out to be negative and significant in all considered regressions; this means that the older the councilor, the less likely to be reelected, and hence the lower the number of terms and the shorter the time period in office.

Education level has been measured in different ways (with dummy variables corresponding to four different educational levels, and/or with dummy variables corresponding to the attainment of a minimum threshold of education, e.g., being graduated or not). In no cases are the variables related to educational level statistically significant, and they are omitted from the basic specification presented in Table 2.

Among the individual characteristics of regional councilors, we also consider the appointment (or not) as a member of the regional cabinet. It is not surprising that the fact of being appointed as a member of the regional cabinet positively and significantly affects the probability of reelection as councilor (and, consistently, the number of terms and years in office). It is worth recalling that the share of female councilors who served as members of regional cabinets is lower as compared to the share of males; thus, women are subject to an adverse effect on reelection, through the channel represented by the opportunity given by the cabinet member role.Footnote 18

Most importantly, in all regressions of Table 2, the dummy variable associated with the female gender is negative and statistically significant. This is our core result: being female per se entails a lower probability of reelection, a lower number of terms in office, and a shorter time period in office–conditional on several other factors. The result will be refined along several directions in what follows.

(b) The institutional characteristics of the region included in the regression design are the number of councilors in the region and regional population (at the time of the first election).

The fact that the number of councilors in the region assumes a positive and significant coefficient means that, ceteris paribus, the larger the number of members of a regional council, the higher the probability of reelection (and hence the larger the number of terms and the years in office). The fact that the regional population has a negative and significant coefficient means that, ceteris paribus, the larger the regional population, the lower the probability of reelection. These results are not in conflict. The number of councilors is indeed related to the population (the correlation between the two series is + 0.559, statistically significant at the 5% level), but what the evidence says is that the amount of population in a region lowers the probability of reelection, for both men and women, while the number of regional councilors to be elected makes the probability of reelection larger.

Among the institutional characteristics, we also evaluated whether special autonomy regions make a difference. The dummy variable associated with the special-statute regions is always not statistically significant. Again, if we insert the two dummy variables corresponding to ordinary- and special-statute regions (instead of the constant term) and formally evaluate the null hypothesis of coefficient equality, this null cannot be rejected in all cases. Thus, we can safely conclude that the probability of reelection (for men and woman) does not vary significantly between ordinary- and special-statute regions.

A different perspective is represented by the consideration of the usual economic-geographic partition of Italy into three macro-areas: North, Center, and South (with South including the Island regions, Sicily and Sardinia). It is well known that regional disparities, in economic and social indicators, are very large in Italy, with Southern regions lagging behind. A huge body of literature deals with Italian economic dualism and the persistent lack of economic convergence (e.g., Brunetti et al., 2011; Fratianni, 2012; Graziani, 1978). Even according to this perspective, we find that the dummy variables associated with these macro-areas have very similar coefficients in algebraic terms, in all estimation exercises concerning regional councilors’ reelection. In particular, in the basic regressions of Table 2, appropriate tests do not reject the null hypothesis that dummy variables associated with Northern, Central and Southern regions are insignificant (that, is the dummy variables have the same coefficient if inserted in the place of the constant term), and for this reason they are not inserted in the basic regressions.Footnote 19

(c) The year of the first election, beyond the constant term, is the third explanatory factor. The year of the first election can be interpreted as a deterministic time trend; its inclusion among the explanatory variables aims to evaluate whether the probability of reelection (and hence, again, the time length and the number of terms in office) has been changing over time. Its effect on reelection is negative and significant. On the one side, this could be a tautological fact: the councilors who were elected more recently clearly have a shorter remaining period in office and fewer occasions to be reelected. On the other side, it could reflect the fact that reelection has recently become more difficult, due, for instance, to greater political instability and fiercer political competition. We prefer the latter interpretation, which we believe is well founded: the time variable measuring the year of first election has a negative and significant effect also in the case of the logit model, where all the subjects in the sample have the possibility of gaining at least one reelection.

Consistently with this result, it is worth reporting that a dummy variable associated with more recent years assumes a negative and significant coefficient, if inserted –instead of the year of first election– in regression equations; this holds irrespective of which “recent year” period is considered.Footnote 20 However, under such a specification, no relevant change in the sign or significance of our variables of interest occurs. For this reason, we disregard time structural break, as the effect of time appears to be appropriately captured by inserting the variable measuring the year of first election. Similarly, if we consider a quadratic form for the deterministic time trend, both the quadratic and the linear term coefficients are significant (with opposite signs, and with sizes showing that reelection is more difficult as time goes on), but this is immaterial to the sign and the statistical significance of other coefficients, hence we prefer to maintain the simpler specification.

5.1 The effect of political orientation

It is interesting to evaluate whether the probability of reelection and the number of terms in office (for all councilors) vary across parties of different political orientations. The answer is affirmative. We classify the councilors according to the political orientation of their party (at the time of the first election). We identify six political orientation classes: left (covering communist and post-communist parties), center-left (including social-democratic parties), center (the Democratic Christian Party and its successors), center-right (including Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and the popular parties usually allied with right-oriented coalitions), right (covering the parties aligning with the right, and populist parties, like the Northern League), and civic parties (including local parties). Of course, the classification of some councilors into these classes can be debatable or unavailable, in some cases. However, the number of dubious cases or unavailable information is rather limited (123, i.e., 2.57% of all cases). Descriptive statistics concerning the political orientation of the councilors under consideration are reported in Table 12 in Appendix, which makes clear that gender discrimination among the group of all regional councilors is present in political parties of all orientations. However, the political orientation for which gender discrimination appears to be less heavy, in regard to the share of elected councilors, pertains to civic and local parties, where the percentage of female councilors is 20.2%, very far away, in any case, from the absence of a gender gap. Evidently, civic parties –in their role as gatekeepers mediating between voters and candidates– appear to be more open toward women, as compared to traditional parties (Kunovich & Paxton, 2005).

In the multiple regression analysis, if a dummy variable is considered for each class of political orientation and inserted in the regression equations under consideration, a clear-cut result emerges: reelection is harder for civic party councilors (both men and women). Specifically, if the dummy variables associated with different political orientations are inserted one by one, only the dummy variable associated with civic parties is statistically significant, with a negative sign, as reported in Table 3.Footnote 21 This means that regional councilors belonging to civic and local parties have a (statistically significant) lower probability of reelection, and, consistently, a shorter average tenure in office and a lower average number of reelections. In general, the probability of reelection does not vary significantly across the other political parties.Footnote 22

Up to this point, we have documented that obtaining reelection for regional councilors in Italy: (a) has been becoming more difficult, as time has gone on; (b) is similar across ordinary- and special-statute regions and across different economic macro-areas (North, Center, South); (c) is more difficult with larger regional population; (d) is more difficult with a lower number of regional councilors to be elected; (e) is more difficult in civic parties, while it is not largely different across parties belonging to traditional political orientations (right-, centrist- and left-wing); (f) is not linked with individual formal educational levels; (g) is more difficult with older age at the time of first election; (h) most important, is characterized by a significant gender bias against women.

6 Features of the gender bias in reelection

In what follows, we focus on the features of the gender bias in reelection. In particular, we evaluate whether and how the gender bias in reelection has changed in interaction with the explanatory factors under scrutiny. We deal with the following research questions: (i) Has the gender bias changed over time? (ii) Is the gender bias related with age and education? (iii) How does the gender bias operate across different political parties? (iv) How does the gender bias operate across different regions? To these ends, we consider the interaction between the gender variable and the other determinants: generally speaking, in the regression specification, the unique dummy variable for women is replaced by split variables capturing the interaction of being a woman with other explanatory variables.

6.1 Gender bias over time

We evaluate whether being a woman changes its adverse effect on reelection over time. We evaluate possible time breaks in 1995 (in correspondence with the reforms moving the electoral system in many regions from purely proportional to a hybrid system, with a majoritarian premium), 2001 (in correspondence with the constitutional reforms empowering the tasks of regions), and 2005 (in correspondence with the electoral reforms introducing, inter alia, gender quotas in the candidate list).Footnote 23

From the descriptive statistics provided by Table 13 in Appendix, one can see that the gender gap characterizes the councilors elected for the first time before 1995, as well as the councilors elected for the first time in the subsequent decades. Perhaps the strength of the discrimination is gradually shrinking if one looks at the last two decades: The percentage of women, among the regional councilors elected for the first time, increases as time goes on, even if the change is very slow and the percentage is still very low –the percentage moves from 8.1% for the councilors elected for the first time before 1995 to 17.5% for the councilors elected for the first time in 2005 and after. The difference in the number of years in office, between male and female councilors, shrinks over time, and also the difference in the percentage of councilors who have obtained at least one reelection shrinks over time, gradually and slowly. In all cases, however, a negative gap characterizes the group of female councilors, irrespective of the time period under consideration.

From multiple regression analysis (Table 4), one can see that the two dummy variables associated with being women, before and after any possible breakpoints under consideration, take negative and significant coefficients, stating that the gender bias in reelection is significant, both before and after the time breakpoints under consideration. More important, in all cases appropriate tests do not reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients are equal, before and after breakpoints. Thus, we can conclude that the gender gap has not changed significantly, in correspondence with specific electoral or institutional reforms. By the way, note also that information criteria and other regression statistics do not provide a clear indication to detect the best breakpoint, from a statistical point of view, among the ones under consideration.

As already mentioned, since 2005, gender quotas for candidacies have been introduced in all regions. The available literature shows that gender quotas for candidate lists may be effective in reducing the sex discrimination in electoral processes. However, we are here evaluating the reelection outcome, and gender quotas in candidate lists may have an indirect effect on reelection. In any case, our interpretation of both the descriptive statistics (Table A(three)) and the multiple regression analysis (Table 4), suggests that the gender gap is slowly diminishing over time. However, there is no compelling reason to believe that the introduction of gender quotas for candidate lists has marked a more significant change compared to previous institutional or electoral reforms concerning different aspects than gender quotas.

If we limit the sample to the 1,748 councilors elected for the first time after 2005, the dummy variable for female gender, though still negative, is smaller in absolute value and significant only at the 10% level. The results of such a regression are not reported in a specific Table in this paper, however, they areconsistent with the evidence presented here in Columns 6 of Table 4, showing that the gender dummy has a lower coefficient, in absolute value, when referring to the women elected for the first time after 2005, as compared to the women elected for the first time in the previous period. Logit estimation shows that being a woman entails, ceteris paribus, a lower probability of (at least one) reelection of 13.5% and 8.7% for female councilors elected for the first time before or after 2005, respectively. Thus, gender discrimination in reelection seems to be less pronounced among councilors elected in more recent times. However, it is important to note that, once again, the observed difference is not statistically significant according to the appropriate formal tests.

6.2 Gender bias and education

Our basic regressions show that education does not affect the probability of councilors’ reelection. However, statistics reported in Appendix (Table 14-part I) show that female councilors have, on average, slightly more elevated education level as compared to males.Footnote 24 An interesting piece of evidence from Table A(four) is that graduation is more effective in increasing the probability of reelection for women than for men. Furthermore, graduated women have, on average, longer time periods in office and a larger number of reelections, as compared to non-graduated women. This is not true for men, who show negligible differences in these statistics between graduated and non-graduated councilors. This allows us to state that education is more necessary for the political success of women than for men. In other words, the reward from education appears to be larger for women than for men. Perhaps, from the voters’ perspective, graduation is a more important signaling device for female than for male candidates; from the candidates’ perspective, graduation is more effective in enhancing self-confidence and self-perceived qualification in women, which makes them more competitive (Fox & Lawless, 2004). Table A(four)-part II shows that the gap in percentage of graduated councilors, between women and men, is rather stable over time, with women steadily displaying a larger share of graduated councilors, but graduation was more frequent for councilors of either sex elected before 1995 (and before 2001) than among those elected starting from 2001.Footnote 25

As indicated by multiple regression analysis, being graduated, for a woman, does not entail a significantly different probability of reelection (or longer length of terms, or larger number of reelections), if the gender dummy variable –that is, the general gender bias– is taken into consideration. In other words, no further statistically significant effect is played by educational levels, provided that the gender bias is considered. Consistently, if one splits the gender variable according to the fact of being graduated or not, both variables have negative and significant coefficients, which are equal according to appropriate formal tests. Note that the coefficient capturing the bias against graduated women is less strong than the coefficient capturing the bias against non-graduated women, if the dependent variable is the average number of years in office or the number of reelections; however, the difference between the two is never statistically significant (Table 5 Cols. 1 and 2).

6.3 Gender bias and age

Councilor’s age at the date of the first election is computed in days and then translated into years. Descriptive statistics show that female councilors are elected, on average, somewhat younger than male councilors. Multiple regression analysis suggests that age operates in a similar way for men and women in determining the probability of reelection: if the explanatory variable “Age” is split into two different variables, “Age for men” and “Age for women,” the two variables have coefficients which are not different according to appropriate tests (not reported in tables; detailed results available from the authors). Moreover, if the dummy variable associated with female sex is split into two different variables according to the councilor’s age being above or below the median age 43, the two split variables have equal coefficients, according to appropriate tests (Table 5 Cols. 3 and 4). Thus, we conclude that the gender bias operates similarly across different ages.

6.4 Gender bias across political parties

Now we evaluate whether gender discrimination in reelection operates differently across parties of different political orientation. The answer seems to be negative, even if some cautionary elements are worth mentioning.

First of all, remember that reelection is more difficult for councilors of civic parties. If we insert the dummy variable associated with civic party in the regression specification, the feature of being a woman in a civic party does not exert a further negative effect in the Poisson model (where the number of reelections is the dependent variable), while it does exert a further negative and significant effect in the logit model. In all cases, women of both right-wing political parties (including center-right) and left-wing political parties (including center-left) suffer from negative discrimination in reelection.Footnote 26 Apparently, women in centrist political parties do not suffer from such gender discrimination; remember, however, that the political parties classified in this way are those in which the percentage of elected women is the lowest. It appears that, in centrist political parties, women’s electoral success is more difficult than in left- and right-wing parties, but reelection does not display gender discrimination. In other words, in the political area where elected women are in the lowest number (that is, the gender discrimination seems to be the most severe during the election process), reelection is not subject to further discrimination; where the number of elected women is (slightly) larger, the adverse bias in reelection emerges neatly.

Interestingly, regression results reported in Table 6 show that the equality of the coefficients associated with the political orientation of women (i.e., being a woman in leftist, centrist, or rightist political parties) is rejected by a formal test in the case of the Poisson model, while it is not rejected in the case of logit model. This means that on the basis of formal statistical tests, the evidence of gender bias against women in reelection is not different across political parties, if one evaluates the probability of at least one reelection, while such equality cannot be accepted if evaluated according to the number of obtained reelections. If we limit the analysis, to evaluate the equality between the coefficients associated with women in left- and right-oriented political parties, such equality cannot be rejected, in all cases: there is no difference in gender discrimination between right- and left-wing political parties.

In sum, there is no sound and clear-cut evidence confirming that gender discrimination operates differently across political parties; perhaps there are some signs that in centrist parties gender bias in reelection is absent, but these are the parties where the bias in election is the strongest.

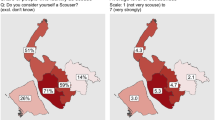

6.5 Gender discrimination across regions

Here we study whether and how the gender bias against women operates across the regions. Firstly, we consider the articulation of Italy into three macro-areas—North, Centre and South. Table 7 reports the results of multiple regression analysis: if the dummy variable associated with the Northern regions is not inserted in the equation specification (Cols. 1 and 2), the dummy variable associated with women in the North emerges to be negative but not always statistically significant,Footnote 27 while the dummy variables associated with women in Central and in Southern regions are always negative and significant. However, in our interpretation, this outcome reflects the fact that –in some of the regression equations under present scrutiny– reelection may be easier, for both men and women, in the Northern regions; hence, it would be a wrong conclusion that gender bias is lower in the North. In fact, inserting the dummy variable associated with the Northern regions, which accounts for the easier reelection in the North (Cols. 3 and 4), the interaction between Northern regions and being a woman reassumes the negative and significant coefficient in the Poisson regression. In the case of the logit specification, the dummy variable for the Northern regions is not significant if the dummy associated with being a woman in the North is inserted, and the latter is negative and significant.

To better understand the possible role of gender discrimination in different geographical macro-areas, we repeated the regressions for the three different macro-areas separately. In all three cases, considering the basic specification, for both the Poisson and the logit model, the gender dummy variable always emerges to have a negative and significant coefficient (Table 8 reports only the coefficient for this variable). This permits us to conclude that the gender bias is present in all geographical macro-areas, and it is disputable that in the Northern regions the bias is milder than elsewhere.

Secondly, we take a different investigation perspective, by considering the repartition of regions according to their budget.Footnote 28 We split the regions into two groups, according to the fact of having a yearly budget smaller or larger than 2 billion euro in 2000. According to this criterion, the small-budget regions are six: Valdaosta, Ligura, Umbria, Abruzzo, Molise, and Basilicata (three Northern, one Central, and three Southern regions); the large-budget regions are the remaining 14 regions. According to such a repartition, the gender bias emerges to be significant in the group of 14 large-budget regions, while it is not significant in the other group of six small-budget regions. This result is robust to the inclusion or not of the dummy “Northern region”; however, such a dummy is significant in the regressions for the large-budget region group, while it is insignificant in the other group. The results (Table 9) consider the specification in which the dummy variable for the Northern regions is inserted only if significant. Thus, a conclusion emerges: if one has to select a group of regions where reelection gender discrimination is statistically less heavy than elsewhere, this group includes the regions with smaller budget. Admittedly, the result is sensitive to the threshold level of budget: for instance, if the threshold for distinguishing small- vs. large-budget regions is set to 3 billion euro (determining groups of 9 and 11 regions, respectively), the gender discrimination emerges to be significant in both groups. Again, in small-budget regions, where the gender bias in reelection appears to be absent, the percentage of female councilors is slightly lower than the percentage in other regions (9.6% vs. 13.1%). Moreover, we cannot be sure that the regions with lower budget are characterized only by this aspect and have nothing else in common. Thus, caution is necessary for concluding that gender discrimination is milder in regions with a more limited amount of resources to manage. Nevertheless, the result is consistent, broadly speaking, with the outcome of different studies,Footnote 29 and we believe that the provided pieces of evidence could warrant future research on the links between gender discrimination and public budgets to manage.

7 Re-candidacy

Provided that a gender bias in reelection does exist, it can be of interest investigating whether this bias is due to the lack of re-candidacy for councilors in office or to the choice of voters. It is possible to obtain reliable information on re-candidacy for 3,867 out of the 4794 councilors of our sample.Footnote 30 Descriptive statistics in Table A(five) show that the missing information on the re-candidacy, regarding 927 councilors, does not affect the gender composition of the resulting sub-sample.

Descriptive statistics clearly suggest that a gender bias against female may affect the re-candidacy: the percentage of re-candidacy is 76.61% for men, and 68.01% for women. Of course, we cannot exclude that this could partly be due to the fact that women decide to give up in a larger percentage than males, but also this occurrence can be seen as a fruit of gender bias.Footnote 31 The existence of a gender bias in re-candidacy is also supported by the outcome of multiple regression analysis: if we estimate a regression equation (with specification such as in Table 2), resorting to the sample made by 3867 councilors for whom reliable information about re-candidacy is available, and having the re-candidacy as the dependent variable, the dummy variable capturing the female gender is negative and significant (See Table 10, Col. 1).

More interestingly, if we repeat the regression on reelection, limiting to the sample of 2,922 councilors who were re-candidate after the first term in office (that is, if we drop from the sample the councilors who are not re-candidate and the councilors for whom the information is not available) we find once again that the dummy variable associated to the female gender is negative and significant (Table 10, Cols. 2 and 3). So, the gender discrimination in reelection is operative even if the analysis is limited to the sub-group of councilors who are re-candidate after the first term in office.

On the basis of the provided evidence, we believe, it is safe to conclude that a gender bias in reelection is operative in both the stage of the decision concerning the re-candidacy and the stage of vote.

8 Exit to higher engagements

One could wonder whether the lower reelection rate for women in regional councils is due to a true gender bias against women or on the contrary to the fact that higher engagements are easier to obtain for women; that is, one could wonder whether election to the national (or European) parliament is easier for female than for male regional councilors. Clearly, and paradoxically, such an “advantage”, if true, could result in apparent gender discrimination in reelection in regional councils. It is easy to check whether such an effect is at work. From official websites,Footnote 32 one can quickly find, for each regional councilor in our dataset, whether he/she has been (subsequently) elected in the national or European parliament. Of course, we are aware that “higher engagements” could include not only the election to parliament but also changes in status like appointments in the private (or public) business sector. However, it makes sense to limit our investigation to the election to parliament, since we are evaluating the gender bias in the political arena. What we aim to do here is simply to exclude the possibility that the documented gender bias against women in the reelection in regional councils is not due to easier election in higher-layer political bodies.

Evidence is clear-cut. Simple descriptive statistics show that 624 out of 4,197 male regional councilors in the present dataset (i.e., 14.9%) were elected to the national or European Parliament, against 80 out of 597 female regional councilors (i.e., 13.4%).Footnote 33 Thus, the percentage of female regional councilors subsequently elected to parliament is lower than the percentage of male councilors. Admittedly, the gap is not large (at least, it is not so large as the gap in the reelection in the regional councils), but it is a gap indeed, against women, and this is sufficient to state that the gender bias emerging in reelection as a regional councilor is not due to an easier “exit for higher engagements” for women. Even if a robust study of the determinants of election to parliament for regional councilors is beyond the scope of the present investigation, we can report that a logit model, employing the present dataset, with the occurrence of election to the national or European parliament as the dependent variable, shows that the dummy associated with female gender is negative, even if statistically insignificant –consistently with the basic statistics summarized above. This lends support to the conclusion that female regional councilors suffer from a (minor, not statistically significant) disadvantage even in the election to parliament.Footnote 34

9 Concluding remarks

The present investigation has documented that women suffer from gender discrimination not only in the competition for entering political councils (which is well documented by a large body of literature) but also in gaining reelection in political councils, after being elected. Taking the population of regional councilors in Italy who have been elected since 1985 and have remained in office at least one year, we have documented that women have experienced a lower number of reelections, that is, a lower number of terms and a shorter period of time in office. This gender gap in reelection is unlinked with the political orientation of parties and rather stable across regions and over time. The gender bias appears to be operative in both the stage of the decision concerning the re-candidacy of incumbent councilors and the stage of vote. Some evidence may suggest that the gender gap in reelection has been shrinking over time, perhaps also due to electoral reforms entailing gender quotas in candidate lists, but the change is not significant from a statistical point of view. Education appears to provide a larger reward for women than for men.

We can summarize the results by stating that women are less able than men to take advantage of their incumbent position. Some possible reasons, proposed to explain the female under-representation in political offices in general, cannot apply to the specific point of the lower rate of reelection. For instance, it is difficult to confirm that the lower reelection rate is due to the fact that women are less inclined to participate in politics. Other considerations are appropriate to specifically explain the lower reelection rate. Women have less experience and, if elected, their performance in office could be lower as compared to their male colleagues. According to some analyses,Footnote 35 women are less corrupt and, when in office, they act in a less clientelist way than males, obtaining lower probability of reelection. Women receive less important assignments and positions when in office. Here, in the case of regional councilors, we have documented that women suffer from a gender bias in appointment as members of the regional cabinet, and the same gender bias may exist for other formal and informal appointments. Perhaps, as a consequence of these possibilities, female councilors may count on fewer resources during the campaign for reelection (Thomsen & King, 2020). A further reason may be that women are perceived as weaker incumbent candidates, so that the efforts and motivations of other competing candidates are harsher, as compared to the case in which the incumbent is male (Brollo & Troiano, 2016).

The evidence provided by the present research, and these considerations, suggest that overcoming the gatekeeper barrier represented by the first election in political councils does not entail, for women, that the gender gap disappears. Considering that the number of women in political councils has been significantly increasing over the most recent decades (in the case of Italian regions, as well as in other political bodies in Italy and over the world), the present investigation suggests that gender discrimination in reelection is more persistent than gender discrimination in initial election.

An element of caution for our results concerns the fact that we do not consider (since we do not have reliable information for all candidates) the effect of the family and political lineage of the candidates. Certainly, for several women in the sample we know for sure that they are daughters, wives or nieces of well-known male politicians, but the available evidence does not allow to make appropriate assessments for the entire sample. In any case, if it were true that the women most likely to win reelection are relatives of male politicians, this would add to the strength of the gender bias.

The larger difficulty for women to gain reelection, as compared to men, has an impact on the continuity of women’s presence in council, and may hence affect the effectiveness of women-driven policy decisions. Thus, measures oriented to reducing gender discrimination in political life cannot be limited to ensuring equal opportunity in entering the arena: glass ceilings are real, and the issue of reelection cannot be overlooked, to provide our societies with real equal opportunity in politics for men and women.

Notes

Gender imbalances in different fields, with a focus on the Global South in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic are the topic of the April 2022 special issue of this journal. See Agarwal et al. (2022).

The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 of the World Economic Forum reports that “Across the 156 countries covered [in 2020…], women represent only 26.1% of some 35,500 parliament seats and just 22.6% of over 3,400 ministers worldwide” (WEF 2021, p. 5). In the 48 countries that held election in 2021, women were elected to 28.6% of the parliamentary seats up for election (IPU 2022, p. 1). In 2000, the percentage of female members of parliaments was 13.1% (IPU 2021, p. 3).

In Italy, the percentage of female members of Parliament –following the 2022 general elections– is 31.0%; in the previous term (2018–22) the percentage was 35.3%. These percentages –which are about double that of 20 years ago– are a little bit larger than the share in local political councils (below 30%). Women represent 22.8% of Italian regional councilors in 2021, compared to 19.6% in 2018. This is clearly lower than the corresponding average in the EU28 countries, which is around 33.3% (see EC 2019, where a specific section is devoted to regional assemblies in European countries).

An increase in female political representation seems to change the priorities in the political agenda, favoring the provision of public goods and infrastructures that better meet the needs of women; for instance, in India, this includes drinking water and roads, as shown by the study by Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2004). The same effective role of female councilors in shaping local public spending has been found in very recent analyses by Ordine et al. (2023) and Steklov et al. (2023) in the cases of Italy and Israel, respectively. However, quasi-experimental evidence on the impact of the increasing share of women in political offices is not univocal. According to Hessami and Lopes da Fonseca (2020), the impact on policy choices is generally more significant in developing countries than in developed countries.

The dataset, built from free and accessible sources, is available from the authors upon request.

Very binding quota systems explain the high presence of women in parliaments of countries like Rwanda (61.3%) and the United Arab Emirates (50.0%); see IPU (2021 p. 4).

Sometimes the quota systems are reinforced by additional mechanisms like the “zipper system” or the conditioned double preference. The zipper system requires the alternation of men and women throughout the candidate list (e.g., in France, in local elections in large municipalities; see Lassebie, 2020), to avoid the relegation of women in the bottom of the lists that could negatively affect the probability of election. The double preference voting rule conditioned on gender prescribes that, if voters are allowed to express two preferences, the two preferences have to go to candidates of different gender (e.g., in Italy, Law 215/2012 on local elections in municipalities with more than 5000 residents; see Baltrunaite et al., 2019).

Panachage permits voters to distribute votes among candidates from different party lists.

The lack of strategic behavior might also explain the extreme case that female mayors in Italy are significantly more likely to be ousted from office through a no-confidence vote in the council, as documented by Gagliarducci and Paserman (2012). Lassebie (2020), with reference to the case of French municipalities, observes that women are more likely to resign than male politicians.

The Italian name for regional council (or assembly) is Consiglio Regionale or Assemblea Regionale, depending on the region. The regional executive cabinet is called Giunta regionale.

Regions still have some autonomy in designing electoral rules; however, in 2020 the national government took action (through a Decree, No. 86–28/7/2020) to impose a modification in the electoral law of a region (Puglia) that in the national government’s evaluation did not meet the requirement concerning preferences.

For instance, the number of regional councilors in Piemonte has passed from 60–62 to 50, in 2014, and it has passed from 90 to 70 in Sicily in 2012, to mention just two cases, the former referring to a region with ordinary statute in Northern Italy, the latter to an autonomous region in Southern Italy.

Operationally, we have deleted the councilors who appear only once in the list of regional councilors in office on December 31 of each year over the period 1985 to 2020.

Generally, in all regions, until around 1995, election in the regional council was a necessary condition for serving as a member of the regional government. This is no longer true after 1995, and it is possible to be appointed in the regional government without having been elected in the council (“external” member of the regional government). As stated in text, if a person is appointed as an external member of the regional government, without having been elected in the regional council, he/she is not considered in our dataset. If a person is appointed in the regional government, after having served as a regional councilor, the years in the regional government are considered as service as councilor.

For the sake of brevity, OLS models are reported only for the first regression exercise. However, they are available upon request for all the regression exercises that follow.

The frequency distribution of the variable reporting the number of reelections is as follows. 0 reelection: 2,625 cases (54.8%); 1 reelection: 1,474 (30.7%, cumulated: 85.5%); 2: 495 (10.3%, cumulated: 95.8%); 3: 143 (3.0%, cumulated: 98,8%), etc. to eight reelections. This is reasonably close to the Poisson distribution.

It is worth mentioning that we also run zero-inflated models as robustness check in addition to the Poisson regressions. However, the logit (or probit) parts of the zero-inflated Poisson models do not present any significant coefficient, while the Poisson-parts remain with all coefficients showing the same sign and significance as in the basic Poisson model. Thus, zero-inflated models do not add any relevant information to our analysis (results are available from Authors upon request).

Interestingly, the dummy variable associated with the appointment in the cabinet is strongly significant on the reelection, even within the sub-sample made up only of all women. In other words, an appointment to the regional cabinet provides and advantage and proves as a differentiator also among female councilors. In any case, the fact that the gender dummy variable, in our model, remains significant means that the gender bias is operative, even conditional on the cabinet appointment.

We acknowledge that –in some specifications, in what follows– the dummy variable associated with the Northern regions emerges to be significantly larger than the dummy variables associated with Central and Southern regions, meaning that reelection, for all councilors, may be easier in the Northern regions. However, this evidence is not robust across specifications and estimators. Moreover, the coefficients of other regressors are often insensitive to the inclusion or not of the dummy associated with the North. We will present the results of regression analysis including the dummy variable for the North, if statistically significant or entailing changes in other coefficients’ estimates, while the dummy variable is omitted if statistically insignificant (in most cases, it is insignificant) and immaterial for other regressor coefficients.

We considered each year between 1995 and 2005 as the possible starting point of the “recent period”; the results are substantially the same across the dates.

If the dummy variables related to political orientation are considered simultaneously in the regression specification, all political orientation dummy variables are positive and significant, but the one referring to civic parties is not significant. The same results emerge if we join left-wing and center-left parties in one party, and right-wing and center-right parties in another joint party. Again, the result holds if center, center-right, and center-left parties are joined in one. Only belonging to a civic party shows a different effect on the occurrence of reelection.

Formally, a test on the equality of coefficients of the dummy variables related to traditional parties (of all orientations from left to right, excluding civic parties), jointly inserted in the regression specification, cannot reject the null of coefficient equality.

The present research does not aim to evaluate whether the different reforms have different effects on councilors’ reelection. However, our interpretation of the results leads to conclude that the different reforms have not entailed substantially different effects in terms of reelection and the gender gap in reelection. See Kittilson and Schwindt-Bayer (2010) and Profeta and Woodhouse (2018), among many others, on the effect of electoral systems and reforms upon gender discrimination.

As already noted, 60.3% of female councilors are graduated, as compared to 56.6% of males. Councilors with secondary school degree represent 35.9% of men and 31.7% of women. The remaining councilors either do not have a secondary school degree or information is missing (5.8% of men and 3.3% of women).

The decrease of the share of graduated elected people, since 2001 in Italy, is also noted in Profeta and Woodhouse (2018), with reference to both national and local levels.

In this section, left- and center-left parties are joined in one class (left), and, similarly, right- and central-right parties are considered as one class (right).

The dummy variable “Female in Northern regions” is not significant in the Poisson specification, as well as in the OLS regressions with the number of terms and years in office as the dependent variable; it is significant at the 10% level in the logit specification and in a Poisson regression with the years in office as the dependent variable.

Budget is only vaguely related to the regional size (in terms of surface or population), as documented also by Table 11 in the Appendix. In fact, small autonomous regions (like Valdaosta or Trentino-AltoAdige) have a much larger budget than the population or territory would indicate.

For instance, Cipullo (2021, p. 31), observes that women are more likely to be elected mayor in Italian municipalities with relatively low GDP growth; his interpretation, however, suggests that the involvement of women in political bodies is easier, the more difficult is the economic situation (see also Yang et al., 2022).

Information on candidacies are not complete, as the candidate lists –available at https://elezioni.interno.gov.it/ (Section “L’Archivio”)– are not present for all regions and all elections, and in some cases there are doubts about the identity of candidates.

The list of the members of the European Parliament is available from several websites, and the list of the members of the Italian Parliament is available from the historical archive of the Italian Senate. See, e.g., https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/it/directory for the European Parliament, and https://www.senato.it/leg/ElencoParlamentari/Parla.html for the two chambers of the Italian Parliament.

Among the 704 (624 male and 80 female) regional councilors of the present dataset, elected to the European or the Italian Parliament, only a few (about 10) were members of Parliament before their election to regional council. According to Italian law, it is not possible to be a member of Parliament and a regional councilor simultaneously.

We can also report that –according to the logit model investigating the probability of election to Parliament for a person included in the present dataset of regional councilors– age has a negative and significant effect; having been appointed as a member of the regional cabinet has a positive and significant effect; and education (as measured by graduation) has a positive and statistically significant effect.

The point that women have higher standards of ethical behaviors, and this entails higher quality of institutions, is far from being a univocal conclusion from available literature. On the one side, Dollar et al. (2001) present cross-country evidence that female politicians are more public spirited and less likely to sacrifice the common good for personal material gain as compared to men. Brollo and Troiano (2016) find that Brazilian female mayors are less likely to engage in clientelism, and hire fewer temporary public employees, compared to males. Baraldi et al. (2022) argue that women are less likely to engage in risky corruption activities because they have higher risk-aversion as also shown by Chaudhuri (2012). On the other side, experimental evidence presented in Maggian and Montinari (2017) shows that high-performance and competitive females are more likely to engage in dishonest behavior than males, and gender quotas have no effect on men and women’s behavior. However, the recent literature review of Hessami and Lopes da Fonseca (2020) drive to the conclusion that higher female representation in political bodies tends to reduce corruption and rent-extraction by those in power, even if this result –at the cross-country level– may be the outcome of spurious correlation (as shown, e.g., by Debsky et al., 2018).

References

Agarwal, B., Venkatachalam, R., & Cerniglia, F. (2022). Women, pandemics and the Global South: An introductory overview. Economia Politica, 39, 15–30.

Baltrunaite, A., Bello, P., Casarico, A., & Profeta, P. (2014). Gender quotas and the quality of politicians. Journal of Public Economics, 118, 62–74.

Baltrunaite, A., Casarico, A., Profeta, P., & Savio, G. (2019). Let the voters choose women. Journal of Public Economics, 180, 104085.

Baraldi, A. L., Immordino, G., & Stimolo, M. (2022). Mafia wears out women in power: Evidence from Italian municipalities. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 193, 213–236.

Besley, T. (2005). Political selection. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 43–60.

Bjerk, D. (2008). Glass ceilings or sticky floors? Statistical discrimination in a dynamic model of hiring and promotion. The Economic Journal, 118(530), 961–982.

Brollo, F., & Troiano, U. (2016). What happens when a woman wins an election? Evidence from close races in Brazil. Journal of Development Economics, 122, 28–45.

Brunetti, A., Felice, E., & Vecchi, G. (2011). Reddito. In G. Vecchi (Ed.), In ricchezza e in povertà: Il benessere degli Italiani dall’Unità a oggi (pp. 209–34). il Mulino.

Chattopadhyay, R., & Duflo, E. (2004). Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica, 72, 1409–1443.

Chaudhuri, A. (2012). Gender and corruption: A survey of the experimental evidence. In D. Serra & L. Wantchekon (Eds.), New advances in experimental research on corruption research in experimental economics (Vol. 15, pp. 13–49). Emerald Group Publishing.

Cipullo D. (2021). Gender gaps in political careers: Evidence from competitive elections. CESifo Working Paper, No. 9075.

Debsky, J., Jetter, M., Moesle, S., & Stadelmann, D. (2018). Gender and corruption: The neglected role of culture. European Journal of Political Economy, 55, 526–537.

De Paola, M., Scoppa, V., & De Benedetto, M. A. (2014). The impact of gender quotas on electoral participation: Evidence from Italian municipalities. European Journal of Political Economy, 35, 141–157.

De Paola, M., Scoppa, V., & Lombardo, R. (2010). Can gender quotas break down negative stereotypes? Evidence from changes in electoral rules. Journal of Public Economics, 94, 344–353.

Dollar, D., Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2001). Are women really the ‘fairer’ sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 46, 423–429.

EC European Commission. (2019). Report on equality between women and men in the EU. European Commission.

EP-DG-Ipol (European Parliament—Directorate for Internal Policies) (2011) Electoral gender quota systems and their implementation in Europe. Note PE-408.309. European Parliament.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. (2004). Entering the arena? Gender and the decision to run for office. American Journal of Political Science, 48, 264–280.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. (2011). Gendered participation and political candidacies: A central barrier to women’s equality in electoral politics. American Journal of Political Science, 55, 59–73.

Golder, S. N., Stephenson, L., Van der Straeten, K., Blais, A., Bol, D., Harfst, P., & Laslier, J. (2017). Votes for women: Electoral systems and support for female candidates. Politics & Gender, 13, 107–131.

Fratianni, M. U. (2012). 150 years of Italian political unity and economic dualism. Rivista Italiana Degli Economisti, 17, 335–356.

Gagliarducci, S., & Paserman, M. D. (2012). Gender interactions with hierarchies: Evidence from the political arena. Review of Economics Studies, 79, 1021–1052.

Graziani, A. (1978). The Mezzogiorno in the Italian economy. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2, 355–372.

Hessami, Z., & Lopes da Fonseca, M. (2020). Female political representation and substantive effects on policies: A literature review. European Journal of Political Economy, 63, 101896.

IPU (2021), Women in parliament 1995–2020. 25 years in review. Geneva: IPU. https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/reports/2020-03/women-in-parliament-1995-2020-25-years-in-review. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

IPU (2022), Women in parliament in 2021. The year in review. Geneva: IPU. https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/reports/2022-03/women-in-parliament-in-2021. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Jones, M. P., & Navia, P. (1999). Assessing the effectiveness of gender quotas in open-list proportional representation electoral systems. Social Science Quarterly, 80, 341–355.

Kittilson, M. C., & Schwindt-Bayer, L. (2010). Engaging citizens: The role of power-sharing institutions. The Journal of Politics, 72, 990–1002.

Kunovich, S., & Paxton, P. (2005). Pathways to power: The role of political parties in women’s national political representation. American Journal of Sociology, 111, 505–552.

Lassebie, J. (2020). Gender quotas and the selection of local politicians: Evidence from French municipal elections. European Journal of Political Economy, 62, 101842.

Maggian, V., & Montinari, N. (2017). The spillover effects of gender quotas on dishonesty. Economics Letters, 159, 33–36.

Niederle, M., Segal, C., & Vesterlund, L. (2013). How costly is diversity? Affirmative action in light of gender differences in competitiveness. Management Science, 59, 1–16.

Norris, P. (2006). The impact of electoral reform on women’s representation. Acta Polıtica, 41, 197–213.

Ordine, P., Rose, G., & Giacobbe, P. (2023). The effect of female representation on political budget cycle and public expenditure: Evidence on Italian municipalities. Economics & Politics, 35, 97–145.

Profeta P., E. Woodhouse (2018). Do Electoral Rules Matter for Female Representation? CESifo Working Paper No. 7101.

Rule, W. (1994). Women’s underrepresentation and electoral systems. PS-Political Science & Politics, 27, 689–692.

Steklov, O., Gofen, A., & Reingewertz, Y. (2023). The influence of women’s representation on social spending in local government. Journal of Urban Affairs, in Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2023.2177551

Thomsen, D. M., & King, A. S. (2020). Women’s representation and the gender pipeline to power. American Political Science Review, 114, 989–1000.

WEF (2021). Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Cologny (CH): WEF. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021. Accessed 7 Aug 2023.

Yang, L. K., Connolly, L., & Connolly, J. M. (2022). Is there a glass cliff in local government management? Examining the hiring and departure of women. Public Administration Review, 82, 570–584.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Catania within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Economic support from PIACERI-2020 (internal university research funding program) is acknowledged. The article also contributes to the GRInS (Growing Resilent, Inclusive and Sustainable) project—Spoke 8 “Social sustainability”, within PNRR—Next Generation EU program (GRINS PE00000018—CUP E63C22002120006). We thank Luigi Bonaventura, Floriana Cerniglia, Giorgia D’Allura, Silvia Pasqua and Gianpiero Torrisi, along with the journal Editor, Ragupathy Venkatachalan, and two anonymous referees, for their helpful comments. The responsibility for the content remains on the authors only.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest or competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cellini, R., Cuccia, T. The gender bias in regional councilors’ reelection in Italy. Econ Polit 41, 47–83 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-023-00320-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-023-00320-z