Abstract

We investigate drivers of preferences for policies of climate change mitigation using the European Social Survey. We find that the share of individuals who agree on (bonus/malus) potentially balanced budget policies that tax fossil fuels and subsidize renewable energies is much less than those who agree only on subsidizing renewable energies. Low levels of education and income are significantly and negatively correlated with the probability of being part of the group of tax-and-subsidy advocates. We also find evidence of a strong seasonal effect, with a significantly higher share of support for the tax-and-subsidy policy being present when interviews are conducted during the hottest months of the year. We discuss the implications of our findings in terms of politically feasible climate change policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate warming and, more generally, environmental challenges have gradually become the most urgent concerns shared at the global level in the last decade. This concern is reflected in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in which environmental sustainability impacts 7 out of 17 goals (goals 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15). SDGs acknowledge that the target cannot be reached with “two hands” only (market mechanisms and enlightened institutions acting as benevolent planners) since citizens’ and corporations’ preferences for responsible (environmentally sustainable) consumption and production (SDG goal 12) play a crucial role in the perspective of a Partnership for the Goals (SGD goal 17).

Consistent with this theoretical and institutional framework, in several countries, national governments are trying to use fiscal policies to strengthen market agents’ incentives to switch from high-carbon to low-carbon production and consumption. Climate change-related fiscal policies use several instruments (tax allowances, tax deductions, subsidies) that generally aim to increase (reduce) tax pressure on activities with a high (low) carbon footprint. By modelling these two choices, it is possible in principle to design budget-balanced policies, including both tax and subsidy measures, or otherwise stressing more than one of the two aspects (i.e., only subsidies), with obvious consequences in terms of government expenditure.

The importance of the above described “multiple hand” approach involving the active participation of citizens and corporations and the political consensus needed for implementing fiscal policies for climate change mitigation motivate the importance of an enhanced focus of economic research on climate change preferences and, more specifically, on preferences for climate change policies.

In our paper, we aim to contribute to this literature by focusing on the specific issue of preferences for climate change policies, thereby providing a contribution from an original specific angle to a literature that focuses more in general on climate change preferences (e.g., beliefs about climate change, opinions about the anthropogenic causes of it, willingness to pay to mitigate it). More specifically, we focus on the ample and detailed information provided in the European Social Survey about the respondents’ two separate opinions regarding taxing fossil fuels and subsidizing renewable energy sources. Our first descriptive goal is to see the distribution of consensus for the softer bonus-only approach (only subsidies on renewable sources) against consensus for the harder bonus/malus approach (both taxes on fossil fuels and subsidies on renewable sources) across countries, the month of the interview, gender, age, income, education and political orientation. In the second part of the paper, we develop an econometric model to identify drivers that significantly affect such preferences. In the final part of our work, we discuss our findings and draw policy implications regarding the most effective fiscal policies to address climate change given the observed preference structure.

The paper is divided into eight sections. In the second section, we provide a short survey of the literature on climate change preferences. In the third section, we outline our research hypotheses. In the fourth section, we provide a theoretical underpinnings of the research hypotheses. In the fifth section we describe our data. In the sixth section, we present our descriptive and econometric findings with their robustness checks, while in the seventh section, we discuss their policy implications. In the eighth section, we conclude the paper.

2 The literature on climate change preferences

Climate change preferences include an articulated set of opinions and beliefs, starting from those regarding the existence of climate change and its anthropogenic causes. Individuals are generally asked whether their moral and social norms induce them to act to change their lifestyles regarding environmental sustainability. In this case, the individual’s decision to act depends, beyond the supporting moral and social norms, on personal efficacy (the belief of one’s own ability to change one’s behaviour) and outcome efficiency (the belief that the individual change can contribute to having a positive impact on the problem) (European Social Survey (ESS), 2018), as well as obvious economic incentives.

Within this broader field of climate change preferences, preferences for climate change policies concern a more specific issue related to the best way to address the challenge from the policymaker’s perspective. They include, among others, opinions about banning fossil fuels, taxing them and subsidizing renewables, which are decisions that obviously have an effect on household budgets.

Regarding the first considered point (beliefs on climate change), the AXA/IPSOS (2012) survey reports a very high average level of beliefs regarding both climate change and its anthropogenic causes in almost all countries, except for the US, where the share of climate change skeptics is higher. Ziegler (2017) finds that conservative political orientation is negatively correlated with the willingness to pay for environmental sustainability in both Germany and the US. However, the same political orientation discriminates against climate change beliefs only in the US and not in Germany, where both right- and left-wing respondents have similar opinions about climate change beliefs (Tjernström & Tietenberg, 2008; Dunlap & McCright, 2008; McCright & Dunlap, 2011; Unsworth & Fielding, 2014). Campbell and Kay (2014) isolate two factors regarding the effects of ideological orientation on climate change aversion. The first is the defence of status quo and system functioning, and the second is aversion towards policies needed to tackle climate change.

Allo and Loureiro (2014) provide a meta-analysis on the role of behavioural norms in climate change preferences and highlight the importance of time preferences and social capital. Tjernström and Tietenberg (2008) find that government trustworthiness affects attitudes and willingness to pay. Douenne and Fabre (2020) investigate climate change preferences in France after the Yellow Vest crisis and find a very low consensus for a carbon tax despite strong climate change awareness. Other studies concentrate on gender differences in environmental preferences and find that women express significantly stronger concerns about environmental sustainability compared to me (e.g., Blocker & Eckberg, 1997; Davidson & Freudenburg, 1996; Greenbaum, 1995; Klineberg et al., 1998; Marshall, 2004). Andor et al. (2018) find that older people are less likely to support the subsidization of renewables than are younger people.

In this literature, there is evidence of a reduced number of studies on policy preferences that aim to reduce climate change. Among them, Brannlund and Person (2012) show that Swedes tend to dislike the term ‘tax’ and demonstrate a preference for instruments that have a positive effect on environmentally friendly technology and climate awareness in an internet-based choice experiment where they are asked to choose between two alternative hypothetical policy instruments. A similar study is conducted by Bannon et al. (2007) on the preferences of Americans for policies reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Another crucial focus of this literature concerns the demographic, attitudinal and contextual role in the analysis of public preferences towards government efforts to reduce climate change. Berk and Fovell (1999) examine the willingness to pay to tackle climate change for a sample of Los Angeles residents by varying several climate change scenarios that differ in ways that are consistent with the existing variations in climate. Many similar studies have been conducted over the years (Aronson & Blake, 2001; Bord et al., 2000; O’Connor et al., 1999, 2002; Kempton, 1991; Leiserowitz, 2006; Zahran et al., 2006).

The original focus of our paper within this literature is the attention to tax and subsidy fiscal policies addressing climate change. These policies are becoming increasingly centre stage and are supported by sound theoretical background. A well-known contribution by Acemoglu et al. (2012) indicates that “directed technical change” is essential to achieving the goal of sustainable growth and that taxes and subsidies are crucial to redirecting corporate incentives towards this goal. The approach also shows that delays in taking the new development path make future adjustments more costly. Such policies are also important to winning over resistance to adaptation to climate change, which has been shown to be cognitively difficult to accept due to conservatism and risk aversion (Tam & McDaniels, 2013). In the same direction, Speck (2017) provides a political economy analysis of the potential of environmental tax reforms by focusing on the interaction between economics and political factors and considering climate and energy policies and demographic changes.

In the analysis of the drivers of tax and subsidies climate change policies, we refer not only to traditional sociodemographic factors but also to variables that are currently unexplored in the literature, such as the climate conditions at the time of the interview. In the section that follows, we explain our research hypotheses that lead to the econometric analysis that follows.

The cross-country tax and subsidy focus made available by the European Social Survey is extremely important for several reasons. In almost all countries, environmentally harmful subsidies still exist,Footnote 1 and most countries are trying to eliminate such subsidies and articulate policies that support the transition to renewable energies financed by taxes (and not subsidies) on fossil fuels. Hence, based on data provided by the ESS database, we can determine three positions with respect to climate change policies. The weakest is being against taxes and subsidies, while the intermediate is being in favour of subsidies on renewables but not on taxes on fossil fuels. The third is in favour of both taxing fossil fuels and subsidizing renewable energy; therefore, this position may suggest support for balanced budget policies that tackle climate change. Even though the ESS data do not explicitly ask opinions about the existing subsidies to fossil fuels (i.e., environmentally harmful subsidies), it is evident that the strongest critical position present in them is that which favours the tax-and-subsidy policy.

3 Our research hypotheses

To our knowledge, only a minimum part of the above described literature has explicitly focused on preferences for climate change policies, while none of the abovementioned works make contributions regarding the specific issue of potentially balanced budget policies that tax fossil fuels and subsidize renewables. We therefore wonder whether their findings on the more general issue of climate change preferences translate into similar results for this specific object of research.

For this purpose, we formulate the following research hypotheses.

The existence of a literature on the relatively higher female sensitivity for environmental sustainability (Torgler et al., 2008; Zelezny et al., 2000) leads us to expect that such sensitivity also translates into a higher propensity for the tax-and-subsidy group (bonus/malus policy). We test whether this is the case and hypothesize as follows:

H1: Women are significantly more likely to opt for the (bonus/malus) tax-and-subsidy policy than are men.

The recent rise of the Fridays for Future protest among the younger generations around the world and the relatively longer time horizon of younger individuals who are likely to suffer for a longer time from the negative future consequences of climate change lead us to expect that these individuals will be relatively more in favour of bonus/malus policies that aim to tackle climate change, net of the impact of their economic condition (Whitehead, 1991; Carlsson & Johansson-Stenman, 2000). We also consider, however, that by controlling for income, we can only partially account for the offsetting factor of the relatively worse economic conditions of younger individuals. In addition, even controlling for income and wealth, life cycle considerations can lead to a relatively higher propensity to save (and therefore lower propensity to pay taxes for fossil fuels) among the younger generations. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H2: Younger people are significantly more likely to opt for the bonus/malus policy than are older people.

There is vast evidence on the role of education in social capital, civic sensibility and willingness to pay for public goods (Helliwell & Putnam, 1999). Additionally, educated individuals are more likely to take preventive measures to avoid problems that are not immediately visible, such as taking insurance to avoid natural disasters (Atreya et al., 2015) or taking prevention against illnesses with no pain, such as diabetes and hypertension (Pandit et al., 2009), compared to their counterparts. We therefore assume that such evidence should translate into a similar higher willingness to agree to tax-and-subsidy policies aimed at defending the public good of environmental sustainability. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H3: More-educated individuals are significantly more likely to opt for the (bonus/malus) tax-and-subsidy policy than are less-educated individuals.

The theoretical and empirical research on the willingness to pay for environmental sustainability mentioned in Sect. 2 clearly shows that a right-wing political orientation is negatively correlated with such a willingness, at least in some countries (Ziegler, 2017). We wonder whether this effect is also present for the climate change policy preferences measured by the ESS and whether the effect persists or disappears once we control for beliefs on climate change and its anthropogenic causes. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H4: Right-wing respondents are significantly less likely to opt for the bonus/malus (tax-and-subsidy policy) compared to left-wing respondents.

It is reasonable to believe the willingness to pay for environmental sustainability and the favour for policies that may also imply higher taxes should depend on the income of the respondents. Consider here, however, that we do not know whether the ESS respondents understand from the tax question whether the tax is directly placed on them (i.e., through higher costs of purchase/usage of non-hybrid or nonelectric cars) or on production sectors. We can reasonably assume, however, that the respondents are somewhat aware that, in the second case, the effect of taxing fossil fuels may also fall upon them in all cases of non-monopolistic suppliers along the product chain of a given good depending on fossil fuels. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H5: Individuals with higher post-tax income are significantly more likely to opt for the bonus/malus policy compared to their counterparts.

It is intuitive to believe that human beings are more willing to pay to avoid a negative event when they see that event coming closer or being more likely to occur. The insurance literature finds support for this hypothesis and shows that microinsurance demand is higher after a flood event (Turner et al., 2014). In the same way, the danger and consequences of climate change are more evident in the hottest months of the year. We therefore expect that seasonality effects in the month of the interview matter, and we hypothesize as follows:

H6: Individuals interviewed in the hottest months of the year are significantly more likely to opt for (bonus/malus) tax-and-subsidy policy compared to those interviewed at other times of the year.

4 Theoretical framework of our research hypotheses

Our research hypotheses have common theoretical underpinnings.

The very simple theoretical framework behind them is a model where the utility function of the respondent has the following two arguments:

that is, the environmental preference (\(EnvQual\))—based on the perceived benefit (harm) of environmental quality (degradation) on one’s own life plus the other-regarding preference for contribution to the environmental public good—and the rest of consumption goods (C). We also reasonably assume the following hierarchy of policy effects on environmental quality, where the tax-and-subsidy policy performs better than the subsidy-only policy, which is in turn better than the no-tax-no-subsidy policy.

By assuming that environmental quality is not an inferior good, the demand for environmental quality is increasing in the income level (hence, given the assumed hierarchy of policy effects, higher income respondents are relatively more likely to opt for the tax-and-subsidy solution than the subsidy-only solution compared to their counterparts). Second, we conveniently assume that respondents with a lower level of education have a reduced perception of the negative effects of environmental degradation on their utility (as well as a lower social capital and willingness to pay for the public good). Third, it is easy to check that in an intertemporal version of our utility function, younger individuals have a higher perception of the negative effect of environmental harm compared to older individuals due to their longer time horizons.

Additionally, hotter temperatures create a priming effect (Bimonte et al., 2020) and make the environmental problem more salient, which, consequently, makes the preference for environmental quality more salient.

Hence, most if not all our research hypotheses can be formulated consistently with this simple and standard theoretical framework.

5 The database

The source for our empirical analysis is the European Social Survey (ESS). The ESS collects information on social preferences, political preferences, beliefs and sociodemographic variables from a large sample of respondents at the cross-country level (a detailed description of the ESS climate preference and opinion variables is provided in Appendix 1). More specifically, we focus our attention on the 8th wave, which was implemented between January 2016 and December 2017, since this is the only wave that collected preferences on climate change and climate change policies. The wave includes representative samples from the following 23 countries: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Russian Federation, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The sample size varies according to the econometric specification considered, ranging from a minimum value of 25,248 (due to missing observations) to a maximum value of 32,172. As explained in the ESS methodological note (ESS, 2018), high-quality translation, rigorous design processes and guidelines regarding data collection all work together to ensure the quality of the database and the reliability of cross-national comparisons.

5.1 Descriptive findings

Consensus for climate change is quite strong among the ESS respondents (approximately 90%), even though only 55.39% of them declare that the climate is “definitely” changing, while 35.5% declare that it is “probably” changing (Table 1). Only 2.2% of the respondents declare that climate is “definitely not changing”. The country with the highest combined share of consensus for climate change (“definitely” or “probably” answers) is Iceland (97.7% against the 90.89 ESS sample average), while the lowest is Israel at 86.3%.

The share of individuals who believe that climate change is not relevantly caused by human activity is very small (1.78% believe it is entirely a natural process, while 6.54% believe it is mainly a natural process). The country with the highest combined consensus (excluding answers where climate change is “entirely” or “mainly” a natural process) is Germany (94.8%), while the lowest consensus (82.7%) is found in Lithuania.

Despite the widespread awareness of the climate change problem and of its anthropogenic causes, there does not seem to be widespread consensus for potentially balanced budget policies that tax fossil fuels and subsidize renewables to tackle it. Only a minority of the respondents (28%) are in favour of the tax-and-subsidy option in the overall sample, while a larger share, i.e., close to a majority (47%), is in favour of the subsidy-only policy. All the rest of the respondents are against taxing fossil fuels and subsidizing renewables, with the exception of a 5 per thousand share of the sample who are in favour of the tax but not of the subsidy. None of them, however, is present in the econometric estimates that follow for missing data on the key variables used in our empirical analysis. We can therefore conveniently assume, based on our sample data, that the only three statistically relevant positions on climate change policies are those in favour of the tax-and-subsidy (bonus/malus) policy, those in favour of the subsidy-only policy only and those against both taxes and subsidies.

The descriptive findings on the tax-and-subsidy group according to educational status highlight a strong positive relationship between education and the tax-and-subsidy option. The difference between the respondents with only a primary school or upper-tertiary school education is quite strong (more than 20%), but even the share of the respondents with an upper-tertiary education (the education class with the highest consensus for that policy) is below an absolute majority (approximately 40%) (Fig. 1a, b).

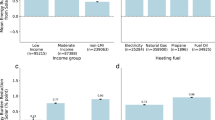

Income distribution also seems to play a relevant role since the share of the respondents favourable to both subsidies on renewables and taxes on fossil fuels increases as we move to the upper part of the income distribution. More specifically, 42% of the respondents from the highest domestic income decile belong to the tax-and-subsidy group versus 22% of the respondents from the lowest decile (Fig. 2a, b).

The descriptive findings on political orientation show that the highest consensus for the tax-and-subsidy (bonus/malus) policy is for left-wing and centre-left wing respondents (with a maximum of approximately 40%), while the consensus drops to 20% for extreme right-wing respondents (Fig. 3a, b).

In regard to the distribution of policy preferences across the countries, the tax-and-subsidy group represents the majority only in Sweden (approximately 54%), while it is at its lowest level (14%) in Poland, even though the Polish respondents are not among those who deny more climate change or its anthropogenic causes among the 23 country respondents (Fig. 4a, b).

The seasonal effect is strong and remarkable, with the share of those favourable to the tax-and-subsidy policy peaking in August, followed by a subsequent decline (Fig. 5a, b). The descriptive evidence on the tentative drivers of preferences for climate change policies will be checked in the econometric analysis that follows, where the effect of each variable considered in our research hypothesis will be evaluated after controlling for the concurring effect of all remaining relevant drivers.

5.2 Econometric specification and findings

To test our research hypotheses, we estimate the following specification:

where the controls include a (0/1) dummy for male gender and dummies for age classes. We also include income dummies that correspond to deciles of the domestic income distribution dummies, and we measure self-assessed political orientation as placement on a 0–10 left–right political scale (the extreme left 0 class being the omitted benchmark).Footnote 2 Dummies for education status are built according to the ISCEDFootnote 3 classification (less than lower secondary, lower secondary, lower-tier upper secondary, upper-tier upper secondary, advanced vocational, subdegree, lower tertiary education, higher tertiary education), with education positions not harmonizable in the ISCED classification being the omitted benchmark.

Other controls include the month interview dummies, which include three “summer” (0/1) dummies (June, July and August). Controls regarding climate change are also added to the estimate. More specifically, the first control (DClimateIsChanging) concerns peoples’ beliefs about climate change, with dummies taking a value of one for those respondents who say that the climate is probably changing or probably not changing, with beliefs about the climate definitely changing being the omitted benchmark. The second control (DClimateChangeHumanOrNatural) introduces dummies that measure whether the respondents believe that climate change is caused by a natural process or by humans (mainly natural, equally between natural and human, mainly human and entirely human), with the opinion that climate change is caused entirely by a natural process being the omitted benchmark. Interaction between the last age group (from 50 years of age onwards) and a high level of education is also added to the estimate to test whether the education of the younger generations, with their stronger concern on sustainability, has a differential effect on our dependent variable.

The specification finally includes dummies for each country of origin (Germany, Sweden, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Switzerland, Belgium, Israel, Czech Republic, United Kingdom, Norway, Finland, Lithuania, Iceland, Ireland, Poland, Ireland, Hungary, Portugal, Slovenia, Estonia), with Austria being the omitted benchmark. The model is estimated with country-clustered standard errors.

We start by estimating a simplified specification that includes only sociodemographic factors (Table 2, column 1). We find somewhat surprisingly that gender and age do not affect climate change policy preferences, with the only exception being the first age cohort since respondents who are less than 20 years old are more likely to be part of the tax-and-subsidy group (vis-à-vis the alternative of being only in favour of the subsidy or against both). Income is shown to be important, as all respondents above the seventh decile are more likely to be in favour of the tax-and-subsidy (bonus/malus) option, and the coefficient magnitude increases as we move to higher income deciles. Political orientation is also important; individuals who locate themselves from the centre to the far right of the political spectrum have negative and significant coefficients and are therefore less likely to be in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy, with respect to the extreme left being the omitted benchmark (with coefficients becoming more negative as we move towards the extreme right). Education is also shown to matter, as individuals with an upper-tier upper secondary education are significantly more likely to be in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy compared to their counterparts. Here, again, the coefficients become larger as we move towards higher education levels. What we measure here is the net effect of education, as its gross impact includes an indirect effect on the dependent variable through higher income (individuals with a higher education also have a higher income due to the well-known return to schooling effects). The month of the interview matters as well (consistent with research hypothesis H06), since the respondents are more likely to declare that they are in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy when they are interviewed in the hottest months of the year (June, July, and August, with a lower magnitude). We interpret our findings by arguing that administering the survey in the hottest months creates a priming effect that makes the environmental problem more salient. In this respect, our findings contribute originally to the literature on priming environmental goals (Halali et al., 2017; Tate et al., 2014) since, unlike the empirical analyses where priming is induced with an explicit treatment, we can interpret our findings by arguing that hot temperatures activate a priming mechanism that is not intentionally and artificially created by the experimenter. Our findings also relate to the more general longstanding literature on the priming effects of temperature on cognition and behaviour (see, among others, Bimonte et al., 2020).

Country effects show that the lowest consensus on the tax-and-subsidy policy is found in some Eastern countries, with Estonia, the Russian Federation and Poland having the highest negative coefficients and therefore being much less in favour of such policy vis-à-vis the omitted benchmarks of Austria and the Nordic countries, who have higher positive values (Table 3). These findings do not reject the hypothesis set forth in the literature that Nordic countries have, ceteris paribus, higher care for the environment and historically higher levels of social capital (see, among others, Rothsteing and Stolle, 2003), with social capital being correlated with willingness to pay for environmental sustainability. Hence, we can infer that the impact of the country variables in the estimates, net of the seasonal effect captured by our month dummies, is related to social capital or other cultural factors not captured by other regressors in the estimate. We find further support for this claim by calculating the average country values of interpersonal trust (ESS question: “People have to be trusted”) and care for the environment (ESS question: “It important to care for nature and environment”). The estimates of the two variables are both significant, and Nordic countries have higher values for both variables. We also show that once these two variables are introduced into the estimate, the Nordic country effects either disappear or fall considerably (Table 4).

We estimate a second specification that is augmented with climate change preferences and beliefs. As expected, support for the tax-and-subsidy policy grows with the strength of beliefs in climate change and in its anthropogenic cause (Table 2, column 2). The introduction of these two variables slightly reduces the magnitude of the other significant variables discussed above but not their significance. This is reasonable since in this specification, we measure the net (and not gross) effects of age, education, political orientation and month of the interview after controlling for preferences and beliefs.

A problem with the ESS is the absence of variables measuring wealth that are highly likely to affect our dependent variable. In the specification of column 3, we introduce one proxy to avoid this omitted variable bias, i.e., the number of members in the household. When introducing this proxy in our estimate, we find that while the number of household members is not significant, the R-squared appears to be greater.

We also introduce into the specification the interactions between the age deciles above 50 and a high (above secondary) leve of education; we argue that education systems have become much more sensitive and oriented towards sustainability in recent times. Hence, the effect of education on policies against climate change is likely to be stronger for younger respondents than for older respondents. Our findings support this hypothesis since the interaction variable is positive and significant (Table 2, column 4).

In Tables A1–A8 and Figures A1–A8 in the ESM Appendix, we calculate the economic significance of our main drivers in the fully augmented specifications (columns 4 and 8). In terms of economic significance, individuals in the highest income decile have an 8% higher likelihood of being in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy than the omitted benchmark of respondents in the first income decile. The effects of education and month of the interview are much larger. More specifically, respondents with the highest (upper tertiary) education level have an 18% higher probability of being in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy vis-à-vis the omitted benchmark of individuals without a formal degree. The magnitude of the season of the year effect is remarkable since interviews held in June or July have an approximately 17% increased likelihood of being in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy, with respect to the average of interviews run in all other months of the year except June, July and August.

5.3 Robustness checks

In columns 5–8 of Table 2, we re-estimate the four specifications of columns 1–4 while eliminating the group of individuals who are against both the tax and the subsidy, thereby leaving in the sample only the tax-and-subsidy group and the subsidy-only group. Our main findings are unchanged.

We perform a further robustness check by estimating our specifications in subsamples of European regions (western, northern, southern and eastern countries) (Tables A9–A12). Some of our results are extremely robust in subsample estimates, while others are not. The month of the interview effect is strong and significant in all four estimates,Footnote 4 and the same occurs for education and for beliefs on climate change and its anthropogenic causes. However, unlike our estimate for the overall sample, political orientation does not make a difference in eastern and southern countries, while income deciles do not make a difference in eastern countries.

To check the correlation between the month of the interview and the average temperature, we calculated the average temperature in the country of the i-th respondent on the day of the interview. We find confirmation that the highest averages are in June (71.2° Fahrenheit) and July (71.5° Fahrenheit), followed by August (61.7° Fahrenheit). This is consistent with the magnitude of the coefficients being higher in the first two months.

In the first estimate (Table 2), we only measure participation in the first (tax-and-subsidy) group without clarifying how the selected regressors discriminate between the choice of the other two (subsidy-only and neither-tax-nor-subsidy) groups. For instance, we know from the estimate that a lower level of education increases the probability of being in the first group but not how it discriminates between the second and the third groups.

Therefore, to answer this second question, we propose a second simultaneous estimate where participation in the first and second groups is tested simultaneously (Tables A13–14).

For instance, when looking at the hot months, we find that they are positive with respect to belonging to the first group and negative with respect to belonging to the second group. This means that in the hottest months, there is a significant shift of respondents from the neither tax-nor-subsidy group to the tax-and-subsidy group, coupled by a significant shift from the tax-only group to the neither tax-nor-subsidy group.

The simultaneous equation estimate does not contradict the results from the single equation estimate in Table 2; rather, it enriches them with further information about transitions from and in the three groups.

We further estimate a transition model where the probability of being in favour of the tax-and-subsidy policy and that of being in favour of the subsidy-only policy are jointly estimated in a two equation system. Again, our main findings remain unchanged (see Tables A13–A14).

6 Discussion of our findings and policy implications

The econometric findings presented in the previous section have several policy implications if the observed econometric significance effects hide causality links.

The significant and robust role of education on preferences concerning policies for climate change mitigation in our estimates suggests that investment in education, even when it does not involve specific formation on climate change at all school levels, can play a crucial role. Consider that the elderly respondents in the ESS survey are less likely than younger respondents to have received robust information on climate change during their school years. However, the stronger effect of education on climate change policies in the younger generation confirms that a stronger focus on environmental issues has a positive effect on such preferences.

The income effect provides evidence in support of the lesson learned through the Yellow Vest crisis. “Just transition”Footnote 5 is fundamental since low-income classes are much less willing to pay for climate change policies compared to their counterparts. The obvious solution is progressive tax/subsidy schemes, such as those enacted by the Italian government after the French experience with higher taxes only on diesel engines only above a given power (considered a proxy of income).

The seasonal effect indicates that consensus on decisions about climate change policies is stronger in the hottest months. It also makes sense of the absence of a linear relationship throughout the entire average temperature range. It is only an extremely warm climate that increases the awareness and focuses on climate change and not the increase or decrease in temperature around colder months. What is also likely to happen is a reinforcement effect through communication. High summer temperatures are more likely to produce events and increase worries in the media about climate change, thereby making public opinion more sensitive to these issues during these months. This finding suggests a nudging strategy of concentrating environmental policy decisions in the hotter months of the year to increase political consensus around policy measures, to reduce the likelihood of hostile press campaigns around the decision times and to avoid potential negative effects on government polls.

The counterintuitive findings on age and gender suggest that governments aiming to promote balanced budget tax-and-subsidy policies should not rely on higher consensus from women and young people.

More generally, our estimates suggest that the much lower (and, in general, minority) consensus on tax-and-subsidy policies should lead governments to carefully evaluate the social costs of environmental policies and help them to understand why carbon pricing policies combined with border adjustment mechanisms, strongly supported by the literatureFootnote 6 to create proper incentives for cological transition, are difficult to implement. Even the removal of environmentally harmful subsidies should take into account these findings and explore alternative ways, such as zero-cost conversions of environmentally harmful subsidies, to achieve an economic benefit linked to the adoption of new environmentally sustainable practices for beneficiaries.

7 Conclusions

Green fiscal policies play a crucial role in environmental transition, and their political implementation crucially depends on patterns of preferences for climate change policies. We investigate the drivers of such preferences using information provided by the European Social Survey. We formulate research hypotheses based on the literature and find that support for the tax-and-subsidy policy is higher for those who are more educated, those who are richer and those whose interviews are conducted in the hottest months of the year, while gender and education do not matter. Respondents with a right-wing political orientation are less likely to support these policies than are left-wing respondents, but only in the northern and western regions.

Our findings therefore suggest not only the importance of “just transition” policies graduating the burden in proportion of income but also that willingness to pay for such a transition also depends on education (and increasingly so given that more recent education programs include more about environmental sustainability), while weather contingencies increase respondents’ sensitivity to the climate change problem.

A caveat for the policy implications from our findings is that the presence of a majority of voters in favour of tax-and-subsidy options does not imply that these policies are politically viable. As is well known, balanced budget policies that have a strong negative impact on small groups (because of the tax) and generate a small benefit on the majority have substantial distributive effects, and they can be hard to implement because of the strong opposition of concentrated and homogeneous groups of stakeholders and the substantial lack of perception of the benefit from the majority. The identification of compensation mechanisms for the losers may be a necessary condition for the implementation of such policies, even when the majority of voters are in favour of them.

Notes

According to Coady et al. (2019), subsidies for fossil fuels at the world level were projected at $5.2 trillion in 2017, corresponding to 6.5% of the world GDP.

The ESS survey asks respondents to report their household's total income, after tax and compulsory deductions, from all sources. Respondents should provide an estimate if they do not know the exact value of their income. After-tax income deciles are calculated at the country level and therefore measure the relative income within a given country.

ISCED refers to the International Standard Classification of Education, which was created by UNESCO to harmonize the education levels of different countries into common categories (those corresponding to the education dummies introduced in our estimate). For details, see http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced

Note that in some subsamples where there are no countries with interviews in one or more of the three summer months, those summer months are excluded from the estimate.

The concept of “just transition” implies that the costs of transformation of the economic system towards environmental sustainability must be born in proportion to everyone’s income capacity in order to avoid posing an unsustainable burden on the low and middle classes. For details about the concept and the political economy of “just transition”, see Heffron and McCauley (2017) and Newell and Mulvaney (2013).

The combination of carbon pricing coupled with a border adjustment tax to avoid “carbon leakage” has gained increasing consensus among economists and scientists. In the U.S., approximately 4000 academicians and policymakers, including 28 Nobel Laureate economists, 4 former chairs of the Federal Reserve and 15 former chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers have signed a common document asking for the implementation of the two measures (https://www.econstatement.org/). Border adjustment is expected to be activated in EU by January 2023 as a source of external funding for the Next Generation EU.

References

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., Bursztyn, L., & Hemous, D. (2012). The environment and directed technical change. American Economic Review, 102(1), 131–166.

Alló, M., & Loureiro, M. L. (2014). The role of social norms on preferences towards climate change policies: A meta-analysis. Energy Policy, 73, 563–574.

Andor, M. A., Schmidt, C. M., & Sommer, S. (2018). Climate change, population ageing and public spending: Evidence on individual preferences. Ecological Economics, 151, 173–183.

Aronson, R. B., & Blake, D. B. (2001). Global climate change and the origin of modern benthic communities in Antarctica. American Zoologist, 41(1), 27–39.

Atreya, A., Ferreira, S., & Michel-Kerjan, E. (2015). What drives households to buy flood insurance? New evidence from Georgia. Ecological Economics, 117, 153–161.

Bannon, B., DeBell, M., Krosnick, J. A., Kopp, R., Aldhous, P., & Magazine, N. S. (2007). Americans’ evaluations of policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Resources for the Future, Stanford University.

Berk, R. A., & Fovell, R. G. (1999). Public perceptions of climate change: A’willingness to pay’assessment. Climatic Change, 41(3–4), 413–446.

Bimonte, S., Bosco, L., & Stabile, A. (2020). Nudging pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from a web experiment on priming and WTP. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 63(4), 651–668.

Blocker, T. J., & Eckberg, D. L. (1997). Gender and environmentalism: Results from the 1993 general social survey. Social Science Quarterly, 841–858.

Bord, R. J., O’connor, R. E., & Fisher, A. (2000). In what sense does the public need to understand global climate change? Public Understanding of Science, 9(3), 205–218.

Brannlund, R., & Persson, L. (2012). To tax, or not to tax: Preferences for climate policy attributes. Climate Policy, 12(6), 704–721.

Campbell, T. H., & Kay, A. C. (2014). Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 809.

Carlsson, F., & Johansson-Stenman, O. (2000). Willingness to pay for improved air quality in Sweden. Applied Economics, 32, 661–669.

Coady, D., et al. (2019). Global fossil fuel subsidies remain large: an update based on country-level estimates. IMF working papers 19.89, p. 39

Davidson, D. J., & Freudenburg, W. R. (1996). Gender and environmental risk concerns: A review and analysis of available research. Environment and Behavior, 28(3), 302–339.

Douenne, T., & Fabre, A. (2020). French attitudes on climate change, carbon taxation and other climate policies. Ecological Economics, 169, 106496.

Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2008). A widening gap: Republican and democratic views on climate change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 50(5), 26–35.

European Social Survey (ESS). (2018). European attitudes to climate change and energy: Topline results from round 8 of the European Social Survey Data Documentation Report, Edition 2.0

Greenbaum, A. (1995). Taking stock of two decades of research on the social basis of environmental concern. In: Metha, M.D., Quellet, E. (Eds.), Environmental sociology: Theory and practice. captus press, Concord, Canada, pp. 125–152

Halali, E., Meiran, N., & Shalev, I. (2017). Keep it cool: Temperature priming effect on cognitive control. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 81(2), 343–354.

Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2018). What is the ‘just transition’? Geoforum, 88, 74–77.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (1999). Education and social capital. No. w7121. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1999

Kempton, W. (1991). Lay perspectives on global climate change. Global Environmental Change, 1(3), 183–208.

Klineberg, S. L., McKeever, M., & Rothenbach, B. (1998). Demographic predictors of environmental concern: It does make a difference how it's measured. Social Science Quarterly 734–753. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42863844?casa_token=mu4_gqW-jcQAAAAA%3A-0VqcUdMKGzvugMr_Ve407IL0J2pLTSiXHO3uX18a4Q-4-HHeb_o2KKeGNTdbdhOaBDldhMEXOzch69sjUyoBLzs1klP8Wt62JpHRx1XM8el2keews&seq=1.

Leiserowitz, A. (2006). Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Climatic Change, 77(1–2), 45–72.

Marshall, B. K. (2004). Gender, race, and perceived environmental risk: The ‘White Male’ effect in cancer alley, LA. Sociological Spectrum, 24, 453–78.

McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change, 21(4), 1163–1172.

Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition.’ The Geographical Journal, 179(2), 132–140.

O’Connor, R. E., et al. (2002). Who wants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions? Social Science Quarterly, 83(1), 1–17.

Pandit, A. U., et al. (2009). Education, literacy, and health: Mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Education and Counseling, 75(3), 381–385.

Speck, S. (2017). Environmental tax reform and the potential implications of tax base erosions in the context of emission reduction targets and demographic change. Economia Politica, 34(3), 407–423.

Survey AXA/IPSOS. (2012). Individual perceptions of climate risks. Available at http://www.axa.com/lib/axa/uploads/cahiersaxa/Survey-AXA-Ipsos_climate-risks.pdf.

Tam, J., & McDaniels, T. L. (2013). Understanding individual risk perceptions and preferences for climate change adaptations in biological conservation. Environmental Science & Policy, 27, 114–123.

Tate, K., Stewart, A. J., & Daly, M. (2014). Influencing green behaviour through environmental goal priming: The mediating role of automatic evaluation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 225–232.

Tjernström, E., & Tietenberg, T. (2008). Do differences in attitudes explain differences in national climate change policies? Ecological Economics, 65(2), 315–324.

Torgler, B., Garcia-Valiñas, M. A., Macintyre, A. (2008). Differences in preferences towards the environment: The impact of a gender, age and parental effect. FEEM Working Paper No. 18

Turner, G., Said, F., & Afzal, U. (2014). Microinsurance demand after a rare flood event: evidence from a field experiment in Pakistan. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 39(2), 201–223.

Unsworth, K. L., & Fielding, K. S. (2014). It’s political: How the salience of one’s political identity changes climate change beliefs and policy support. Global Environmental Change, 27, 131–137.

Whitehead, J. C. (1991). Environmental interest group behaviour and self-selection bias in contingent valuation mail surveys. Growth and Change, 22, 10–21.

Zahran, S., et al. (2006). Climate change vulnerability and policy support. Society and Natural Resources, 19(9), 771–789.

Zelezny, L. C., Chua, P. P., & Aldrich, C. (2000). Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 443–457.

Ziegler, A. (2017). Political orientation, environmental values, and climate change beliefs and attitudes: An empirical cross country analysis. Energy Economics, 63, 144–153.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1: Description of climate preference and opionion variables in the European Social Survey

Appendix 1: Description of climate preference and opionion variables in the European Social Survey

-

1.

Variable “inctxff”: Favour increase taxes on fossil fuels to reduce climate change

Question:

To what extent are you in favour or against the following policies in [country] to reduce climate change? Increasing taxes on fossil fuels, such as oil, gas and coal.

Values | Categories |

|---|---|

1 | Strongly in favour |

2 | Somewhat in favour |

3 | Neither in favour nor against |

4 | Somewhat against |

5 | Strongly against |

7 | Refusal |

8 | Don't know |

9 | No answer |

-

2.

Variable “sbsrnen”: Favour subsidise renewable energy to reduce climate change

Question:

To what extent are you in favour or against the following policies in [country] to reduce climate change? Using public money to subsidise renewable energy such as wind and solar power.

Values | Categories |

|---|---|

1 | Strongly in favour |

2 | Somewhat in favour |

3 | Neither in favour nor against |

4 | Somewhat against |

5 | Strongly against |

7 | Refusal |

8 | Don't know |

9 | No answer |

-

3.

Variable “ccnthum”: Climate change caused by natural processes, human activity, or both

Question:

Do you think that climate change is caused by natural processes, human activity, or both?

Values | Categories |

|---|---|

1 | Entirely by natural processes |

2 | Mainly by natural processes |

3 | About equally by natural processes and human activity |

4 | Mainly by human activity |

5 | Entirely by human activity |

55 | I don't think climate change is happening |

66 | Not applicable |

77 | Refusal |

88 | Don't know |

99 | No answer |

-

4.

Variable “clmchng”: Do you think world's climate is changing

Question:

You may have heard the idea that the world's climate is changing due to increases in temperature over the past 100 years. What is your personal opinion on this? Do you think the world's climate is changing?

Values | Categories |

|---|---|

1 | Definitely changing |

2 | Probably changing |

3 | Probably not changing |

4 | Definitely not changing |

7 | Refusal |

8 | Don't know |

9 | No answer |

Construction of the variables for our estimates

Variable | |

|---|---|

Tax and Subsidy | “Inctxff” = 1, 2; “sbsrnen” = 1, 2 |

Only Subsidy | “Inctxff” = 3, 4, 5; “sbsrnen” = 1, 2 |

Climate Change: Human or Natural | Same construction of “ccnthum” (Excluding categories with values greater than 5) |

Climate is changing | Same construction of “clmchng” (Excluding categories with values greater than 4) |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Becchetti, L., Conzo, G. Preferences for climate change-related fiscal policies in European countries: drivers and seasonal effects. Econ Polit 39, 1083–1113 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-022-00259-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-022-00259-7