Abstract

Using an original database on medium and large Italian firms built by merging the Rilevazione Imprese e Lavoro run by INAPP in 2010 and 2015 with the AIDA archive by Bureau Van Dijk, we show that the trend of the labour share differs along the labour share distribution. We carry out Unconditional Quantile Regression decompositions to explore the main drivers behind this heterogeneity. Thus, we contribute to the literature on the dynamics of the labour share since we investigate phenomena which cannot be observed through a macro perspective or by looking at a single parameter of the labour share distribution. After including in our specifications several firm-level characteristics and considering composition effects, we find that outsourcing is the main factor which plays a role in reducing the labour share along the distribution. Further different mechanisms act in the various parts of the distribution: unionization contributes to increase the labour share at the top of the labour share distribution, while the introduction of some forms of product (process) innovations is associated with a negative (positive) change in the labour share for those firms at the bottom of the labour share distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The decline of the labour income share experienced by most advanced economies over the last decades raised serious concerns on the spread of income inequality (Atkinson 2009; Glyn 2009; Checchi and García-Peñalosa 2010). The decline in the labour share evolves together with the widening of market-income inequalities due to the uneven distribution of capital income compared to labour (see for a detailed discussion García-Peñalosa 2010). As in most advanced economies, in Italy the labour share has decreased from 66.9% in 1970 to 50% in 2018 (AMECO) reflecting an increasing profit share in total income (Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014). More specifically, the Italian labour share raised until 1970s, then it has started to strongly decrease between the late 70s and the 90s, and finally, since the 2000s, in contrast with the experience of other OECD countries, it has gone slightly up again (Torrini 2016; Schwellnus et al. 2018). This evidence has fueled an intense debate on the determinants of the labour share. Academic studies and policy reports proliferated with the aim to explain trends in the labour share. Explanations range from: (1) technological change—suggesting an increasing substitution between labour and capital; (2) institutions—looking at unionization and bargaining of workers; (3) globalization; (4) market share and rising of “superstar firms”; (5) financialization (see Schwellnus et al. 2018 for a discussion).

Most empirical studies focusing on the determinants of the labour share are based either on country data (European Commission 2007; Checchi and García-Peñalosa 2010; Young and Lawson 2014) or industry-level data (Azmat et al. 2012; Hutchinson and Persyn 2012; Elsby et al. 2013; Pianta and Tancioni 2008; Bogliacino et al. 2017; Young and Zuleta 2018).

Firm level evidence is scarce although very informative. In particular, GDP aggregates value-added of different industries and, consequently, of different firms whose factor shares mirror different technological opportunities and labour conditions. Therefore, despite a micro-level study does not necessarily imply results valid also for the aggregate labour share, it allows to tackle firm heterogeneity and to focus on within-firm strategies impacting on how rents are shared between capital and labour. As discussed by Siegenthaler and Stucki (2014), most of labour income determinants are related to firm’s decisions and the functional distribution of income is ultimately decided at the workplace level (Dünhaupt 2013).

Furthermore, a firm-level analysis allows to overcome several measurement issues concerning, for example, how to account for employment and self-employment in income shares (Gollin 2002; Glyn 2009; D’Elia and Gabriele 2019). Eventually, a firm-level approach enables to control for composition biases due to changes in the sectoral composition of the economy or changes in the composition of firms (Arpaia et al. 2009; De Serres et al. 2001; Young 2010; Elsby et al. 2013).

Trends in the labour share are to a large extent driven by the comparative evolution of average wages and labour productivity (OECD 2015). If average wages increase more rapidly than average labour productivity, the labour share increases. Conversely, as clearly stated in OECD (2015), when the growth in average wages lags the growth in labour productivity, the labour share declines. Against this background, the Italian productive structure is characterized by high dispersion of productivity and wages, namely high-productive and low-productive firms coexist and pay to workers different wages (see Bugamelli et al. 2018; Cirillo and Ricci 2020). Dispersion in productivity is a well-known empirical fact (Syverson 2011) as well as high dispersion in wages (Barth et al. 2016). We link this evidence on productivity and wage dispersion across establishments to the fact that a declining/increasing labour share can be the result of wages growing less/much faster than productivity or, conversely, it would be a pure contraction/expansion of wages if valued added (productivity) does not change over time. This consideration leads us to investigate the determinants of the labour share along its distribution acknowledging that position of firms in the upper/lower part of the distribution depends on the relative growth of productivity with respect to wages.

Furthermore, descriptive aggregate evidence (mainly industry-level studies) on Italy shows that changes in the labour share are mainly due to within-industry decline (OECD 2012). The reallocation of resources from high and mid-labour-share firms towards low labour-share firms played a minor role in Italy (Landini et al. 2020). Changes in the Italian labour share cannot be totally explained by intra-industry restructuring or by firm-exit and firm-entry. This leads us to focus also on wage-setting processes within firm (Bell et al. 2019; Card et al. 2018).

Based on these arguments, this paper proposes a firm-level study of the determinants of the labour share stressing the heterogeneity of Italian firms. Technology, internationalization, and union (labour market policies) have been studied as main drivers of labour share changes at the macro level, however their functioning might vary across establishments given existing heterogeneities of firms in terms of productivity and wages.

To which extent are these drivers varying along the distribution of firms’ labour share? Our hypothesis is that these channels differently affect the labour share depending on the productivity of the firm and on the average wage paid to workers. To be profitable on markets, more productive firms are those where strategies based on productivity growth are implemented. On the contrary, low productive firms are those where cost-competitiveness strategies aimed at increasing efficiency by reducing the relative weight of labour and wages are preferred (Vivarelli and Pianta 2000; Guarascio and Pianta 2017). While in the first case the bargaining between owners and workers is based on the redistribution of gains deriving from productivity growth, in low productive firms the bargaining is mainly based on labour costs. Of course, labour market institutions play a major role along the entire distribution.

This paper contributes to the existing literature in two different ways. Firstly, it sheds lights on heterogenous dynamics of the labour share experienced by medium-large Italian firms at different points of the labour share distribution which cannot be captured by observing a unique parameter of the firm-level distribution (the mean) or focusing on the labour share at the macro level. Secondly, it investigates determinants of the dynamics of the labour share focusing on three main drivers which can act in different ways at different percentiles of the labour share distribution. Specifically, among all possible mechanisms behind the evolution of the labour share, we focus on a comprehensive set of aspects related to globalization patterns (FDI, outsourcing, share of export, foreign group), technological change (process and product innovation), labour market institutions and bargaining power of labour (share of union members, share of temporary workers). We evaluate if and to what extent these three drivers explain different patterns of the labour share dynamics at different points of the labour share distribution.

To this aim, we use the recently built “RIL-AIDA” dataset obtained by merging the 2010 and 2015 waves of the periodical survey Rilevazione su Imprese e Lavoro (RIL), carried out by the National Institute of Public Policy Analysis (INAPP), which contains information on a representative sample of the population of medium-large Italian firms, with the Analisi Informatizzata delle Aziende Italiane (AIDA) database which records information on the balance sheets of the universe of Italian non-agriculture/financial corporations. This dataset is particularly useful because it allows us to explore the dynamics of the labour share at the firm level relying on a wide set of information on firms’ characteristics.

To evaluate the importance of each driver along the labour share distribution we use a two-step econometric approach. Firstly, we estimate at different parameters of the labour share distribution the association between the labour share and several firm-level characteristics using Unconditional Quantile Regression (UQR) originally proposed by Firpo et al. (2009). Subsequently, for each selected parameter of the distribution, we perform a detailed decomposition analysis of the variation of the labour share occurred between 2010 and 2015 to distinguish between composition and unexplained effects. This methodology, presented in Fortin et al. (2011), has been recently exploited to decompose in composition and wage structure effects the evolution of labour earnings inequality recorded in Canada (Firpo et al. 2018), in European countries (Pereira and Galego 2019) and in Germany (Biewen and Seckler 2019). In this paper, we apply the same econometric approach to decompose labour share variations at three different percentiles (P25, P50, P75) of the labour share distribution to highlight heterogeneous patterns and mechanisms.

It is worth noting that, although our analysis and results cannot be generalized to other country because we focus only on the Italian case with its unique context in terms of culture, institutions, and policies, our method can be easily extended to other countries to distinguish between composition and unexplained effects and to take into account the evolution of firms’ characteristics over time at different quantiles of the labour share distribution. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that cross-country comparisons in firm-level labour share show limitations given profound differences in institutional settings across countries.Footnote 1 In addition, cross-country comparisons of firm-level dynamics are exposed to several weaknesses due to data characteristics (Böckerman and Maliranta 2012) and, econometrically, they can be more easily compromised by presence of omitted variable and parameter heterogeneity biases.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 summarizes the hypotheses put forward by the literature on the labour share dynamics and illustrates our framework; Sect. 3 presents the data used to implement the analysis. Section 4 provides descriptive evidence on trends of the labour share along the distribution and firms’ characteristics. Section 5 presents the estimation strategy used to implement the detailed decomposition analysis. Section 6 discusses the main results. Section 7 concludes.

2 Setting the framework: from macro to micro

The question of how rents are distributed among the factors of production, the core of the Classical economics, has gained renewed attention because of a substantial decline in the labour share of national income since the 1970s in most of European countries. Indeed, many studies have documented a fall in the labour share for most developed countries over recent decades (Elsby et al. 2013; Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014; Piketty 2014). The OECD (2012) has observed that, over the period from 1990 to 2009, the share of labour compensation in national income decreased in 26 out of 30 advanced countries for which data were available. The median (adjusted) labour share of national income across developed countries fell from 66.1% to 61.7% (OECD 2015). Other international institutions have observed a similar downward trend (IMF 2007; European Commission 2007; BIS 2006). The decline of the labour share has shed new lights on the functional distribution of income between capital and labour re-opening the debate on the main drivers that affect both capital and wages growth. The new evidence on the fall of the labour share contrasts with the predictions of a constant labour share of most macroeconomic models.

The renewed attention toward factors remuneration goes in hand with the debate on economic inequality. Indeed, the growth of inequality that took place in the post 1980s has been increasingly affected by the functional (i.e. across factors of production) distribution (OECD 2008,2011; Bogliacino and Maestri 2014; Piketty 2014). The decline of the labour share implies an increase in economic inequality in the developed world mainly because labour income is much more evenly distributed than non-labour income (Atkinson 2009; Glyn 2009; Garcìa-Peñalosa 2010; Checchi and Garcìa-Peñalosa 2010). On the contrary, the capital share appears to increase in most OECD countries (Arpaia et al. 2009; Stockhammer 2013; Schlenker and Schmid 2015).

Focusing on empirical studies on the labour share, a major distinction concerns the level of the analysis. Many empirical studies are based on country data (see, e.g., Checchi and Garcia-Peñalosa 2010; Hogrefe and Kappler 2013; Young and Lawson 2014; Damiani et al. 2018; Young and Tackett 2018). Some studies use industry-level data (Azmat et al. 2012; Hutchinson and Persyn 2012; Elsby et al. 2013; Alvarez-Cuadrado et al. 2018; Pianta and Tancioni 2008; Bogliacino et al. 2017; Young and Zuleta 2018). Only few studies have focused on firm-level data (Growiec 2012; Autor et al. 2020; Adrjan 2018; Guschanski and Onaran 2018). The advantage of using firm-level data lies in the possibility to take into account composition biases (Siegenthaler and Stucki 2014). Indeed, an important fraction of the decline in the aggregate labour share can be attributed to changes in the sectoral composition of the economy (Solow 1958; De Serres et al. 2001; Arpaia et al. 2009; Young 2010; Elsby et al. 2013). Autor et al. (2020) underline that the reallocation between firms is a central factor in the fall of the labour share instead of a within-firm phenomenon. However, this result is debated and suggests the relevance of controlling for composition effects given by reallocation of firms across sectors and reshaping of the structure of economies toward services.

Studies which use country-level data usually face several measurement or methodological issues. In the first place, it is not easy, at the macro level, to consider the contribution of intangibles to income, or the imputation of labour and capital income earned by entrepreneurs, unincorporated business, and self-employment. Second, aggregate studies generally do not explicitly consider how much of the fall of the labour share is due to changes in the composition of firms, rather than by within-firm changes. Furthermore, unlike country-level studies, firm-level works based on a panel structure allow controlling for different types of endogeneity and unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity of firms (Siegenthaler and Stucki 2014).

The lack of firm-level studies is partly due to the availability of adequate data including information on labour cost, value-added, as well as financial variables and other potential drivers for wage determinants. Moreover, as acknowledged by Siegenthaler and Stucki (2014), even the analysis of the determinants of the labour share performed at the micro level would require an adequate time span since factors shaping labour changes occur in the medium-long term and should be distinguished by short-term business cycle effects. From this point of view, one advantage of country and industry level studies derives from the possibility of considering long-time span variations in factor remunerations over decades focusing on structural factors reshaping employment, occupations, wages, and profits.

Beside the level of analysis, there is a large consensus on the main causes of the recent decline in the labour share. Many empirical studies have tried to investigate the determinants of the functional distribution of income focusing both on capital and labour emphasizing the role of technical change. Indeed, in the economic theory the idea that technical change is not neutral is probably due to Hicks (1963), although labour saving bias of machines was clearly present also in Marx and Ricardo that suggest that labour saving innovation is driven by falling prices of capital. This theoretical discussion of the 1960s received a renovated interest in the 1990s debate over the massive introduction of ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) and its effect on the dynamics of wages (Berman et al. 1994).

Focusing on the capital-labour elasticity of substitution, Neoclassical economists put forward the argument that the cost of capital relative to labour has fallen due to the introduction of ICT; this change in relative capital price should affect factor shares when the capital-labour elasticity is greater than one (Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014). Bentolila and Saint-Paul (2003), building on a frictionless neoclassical growth model and assuming constant return to scale of production function, argue that the labour share is a unique function of the capital-output ratio. In this framework, if capital and labour are substitutes, a higher capital intensity reduces the labour share; conversely, if capital and labour are complements, capital can even increase the labour share. However, the empirical literature does not support the role of relative capital price reduction to explain the fall of the labour share that occur when the capital-labour elasticity of substitution is greater than one. There is evidence of elasticity of substitution below one (Chirinko 2008; Oberfield and Raval 2014; Lawrence 2015) and the assumption of labour-augmenting technological progress does not have support in the empirics.

Departing from the Neoclassical perspective, Pianta and Tancioni (2008) analyze the effect of technical change, distinguishing product and process innovation, on wages and profits. They found that profits are driven by the ‘Schumpeterian’ effects of new products. Wages, on the contrary tend to be pushed upwards by new products, in highly innovative sectors, whereas process innovation drive them downward in low tech industries. On this line, Guellec and Paunov (2017) study the relationship between digital innovation, market structures and the distribution of income. Building on a Schumpeterian perspective, they argue that new digital innovation—allowing for economies of scale and low costs of innovation—increases creative destruction and high market rents for investors and top managers, but they reduce wages. “Winner-take-all market” structures affect the distribution of income facilitating higher market concentration and higher market rents leading to labour share reduction. Other evidence supporting the effects of “winner-take-all markets” on the decrease in the labour share includes Barkai (2020) and Autor et al. (2020). Barkai (2020) detects a negative relationship between labour share and markups confirming the link between the former and rent sharing. On the same line, Autor et al. (2020) show for US and other developed countries that the decline in the labour share is stronger in those industries with stronger market concentration that is associated with more technology-intensive industries.

Another stream of studies has focused on the effects of globalization on the labour share in high-income countries detecting a negative relationship between the intensification of competition and the entry of labour-abundant countries having a wage-compressing effect on workers’ remuneration (ILO 2008; IMF 2007). Several studies have shed lights on the redistribution from labour to capital occurring through offshoring (Burke and Epstein 2001). At the sectoral level, Bogliacino et al. (2017) identify the impact of demand, innovation and offshoring on capital and labour remuneration detecting a negative relationship between offshoring and low-skilled workers’ remuneration. Innovation and offshoring favor high-skilled workers, offshoring exerts downward pressure primarily on low-skilled wages and profits are positively correlated with high skill wages, negatively correlated with medium-skill wages and not correlated with low skill wages. Overall, the empirical evidence has not been conclusive on the relationship between the labour share and offshoring. Guerriero and Sen (2012) find a positive effect of international trade on the labour share. Autor et al. (2020) underline that sectors not exposed to import have also recorded a reduction in labour share as traded sectors, therefore the role of international trade on labour remuneration needs to be qualified in terms of skills. According to Bell and Van Reenen (2013), the extent and size of gains from offshoring are limited.

Other studies focus on the role of institutional factors and deterioration of labour power: so-called “declining worker power” hypothesis (see Stansbury and Summers 2020, for a detailed discussion). Factors such as union density, minimum wage legislation, unemployment benefits and union coverage deserve attention. The decline of union density, measured by the number of trade union members as a percentage of employees, is usually positively correlated with a fall of the labour share. Indeed, the decline in union density is linked to the weakening of workers’ bargaining power negatively affecting workers’ ability to negotiate a larger share of labour compensation (OECD 2015).

From a country-level perspective, Damiani et al. (2018) analyze the role of the liberalization of temporary contracts in some EU countries detecting a strong negative relationship between legislations favoring the extensive use of temporary contracts and the labour share. The diffusion of temporary contracts modifies the nature of employment relations making more difficult for trade unions to recruit members and therefore leading to labour share compression (OECD 2012).

As underlined in OECD (2011) and Bogliacino and Maestri (2014), institutional reforms in the labour markets appear to be responsible for most of the change in wage inequality and factors remuneration. Bogliacino et al. (2017) highlight that the way in which rents are shared should be made dependent on a bargaining between labour and capital (where institutional factors certainly play a role).

More recently, the analysis on the relationship between firm’s labour share and technology has been articulated at the local labour market level starting from the idea that the effects of technology adoption on labour might be offset within local labour markets (Ciarli et al. 2018). On one hand, initial industrial specialization and composition of skills in routinised and non-routinised jobs might affect the rate of adoption of technologies (Autor and Dorn 2013; Goos et al. 2014); on the other hand, it can influence the bargaining power of workers (Guellec and Paunov 2017). As suggested by Adrjan (2018), local labour markets with a greater proportion of groups with a lower bargaining power, for example short-term or part-time workers, are associated with a lower labour share, and firms located in those local labour markets can take advantage from the presence of workers less able to affect rent-sharing policies.

From a different perspective, a very recent stream of studies has emphasized the role of financialization on the firm-level labour share detecting that the increased shareholder value orientation has exerted a downward pressure on the labour share, while technological change and market concentration did not play an important role for the decline of labour share (Guschanski and Onaran 2018).

To sum up, several causes of the declining trend in the labour share have been proposed. On one hand, some explanations consider the role of technological change and its impact on prices of capital relative to labour, which, according to a neoclassical framework, can push firms to substitute labour with capital. On the other hand, following a neo-Schumpeterian approach, another explanation focuses on the increase of firms’ market share and market power through the introduction of digital innovation and the opening of new markets. Finally, another stream of studies has explicitly considered the role of deregulation and other institutional factors shaping labour market relations in favor of capital. The literature has discussed both explanations at the country and at the sectoral level, disregarding the role of firms’ heterogeneity in terms of productions and wage-setting processes.

In this work, we argue that the main drivers of the labour share of Italian firms are not equally affecting the internal distribution of income and a certain degree of heterogeneity should be taken into account when analyzing the internal subdivision of rents.

2.1 Theoretical framework

Although firms are not pure profit-maximizerFootnote 2 they may rely on two broad strategies to be competitive: (1) those impacting on the value-added growth and, therefore, on productivity—such as the introduction of product technologies and internationalization; (2) those affecting their internal structure of labour costs—by introducing process technologies or outsourcing labour intensive activities abroad to save labor costs. More specifically, firms’ strategies can be linked to technological competitiveness or, alternatively, cost competitiveness (Vivarelli 1995; Vivarelli and Pianta 2000). If a strategy of technological competitiveness based on the introduction of new products and the creation of new markets prevails, we should expect strong increases in productivity. Conversely, a cost competitiveness strategy grounds on labour-displacing process innovations. In short, some firms will introduce product innovations to boost productivity (value-added) and realize some profits via productivity growing faster than labour costs; while other firms will try to survive on the market registering positive profits by cutting labour costs and therefore decreasing wages. Internationalization firm strategies can be framed similarly. While exporting high value-added products represents a way to improve productivity and to realize profits; outsourcing productions is a strategy to explicitly put pressure on labour (Stansbury and Summers 2020).

The bargaining of rents within firms is directly influenced by the relative power of workers (for instance, union density). To which extent are these drivers varying along the distribution of firm labour share? As stated in the previous Section, our hypothesis is that these channels differently affect labour share depending on the productivity of the firm and on the average wage paid. While in the case of high-productive firms the bargaining between owners and workers is based on the redistribution of gains deriving from productivity growth, in low productive firms the bargaining is mainly based on the labour cost. Of course, labour market institutions are likely to play a major role along the entire distribution.

Several outcomes of the bargaining process might be hypothesized.Footnote 3 We may expect an increase in the labor share because of the introduction of product innovations due to the creation of temporary monopoly rents (Van Reenen 1996). Process innovation is expected, conversely, to compress labour share: workers might be substituted by machines leading to an increase in the capital share of firms. However, both process and product technologies have a differentiated impact on skilled and unskilled workers. Therefore, the outcome depends on the relative composition of skilled/unskilled labour within-firms.

Firms’ strategies of internalization entail several activities. Low productive and low capital intense firms are usually engaged in outsourcing which means reallocation of production. A few empirical studies using firm-level data confirm that imports and offshoring have tended to deteriorate the bargaining power of workers (Dumont et al. 2006). We expect that outsourcing should deteriorate workers bargaining power everywhere, but the effect should be relative more strong among labor-intensive firms where workers are more exposed to competition of foreign low-skilled workers.

In what follows, we articulate these points by showing descriptive evidence on labour share evolution across firms and, in the empirical section, we explore the main drivers concerning globalization, labour market institutions and technological change.

3 Data

The data used in the analysis are drawn from the last two waves of the RIL dataset conducted by INAPP in 2010 and 2015 on a representative sample of Italian firms. Each wave interviews over 30.000 firms operating in non-agricultural private sector. A subsample of all firms included in a given wave (around 30%) is followed over time making the RIL dataset partially panel. The RIL data collects a rich set of information about the composition of the workforce, including the amount of training investments, hiring and separations, the use of flexible contractual arrangements, the asset of the industrial relations and other workplace characteristics. Moreover, the data contains an extensive set of firm level controls, including the managerial and corporate governance characteristics, productive specialization, and other firm strategies (such as innovation and export activities). However, the RIL dataset provides incomplete information on financial and accounting variables, which had to be recovered from another source. To this purpose, we use the national tax number (codice fiscale) to merge RIL data with AIDA archive provided by the Bureau Van Dijk. The AIDA dataset offers comprehensive information on the balance sheets of almost all the Italian corporations operating in the private sector, except for the agricultural and financial industries. More specifically, this dataset contains variables such as cost of labour, revenues, value-added, net profits, book value of physical capital, total wage bill and raw-material expenditures taken from the balance sheets. By exploiting this detailed information, we are able to calculate indicators of labour productivity (value-added per employee), fixed capital (the total amount of physical asset per employees), and many others. To keep prices constant, we deflated all monetary variables using specific deflators (the index of industrial production) provided by the Italian National Statistics Institute (ISTAT). The resulting “RIL-AIDA” merged sample was restricted to limited liability firms that disclose detailed accounts in accordance with the scheme of the 4th Directive CEE.

The value of the labour share is the core variable of our analysis and it is computed as the ratio between the cost of employees and the value-added as reported in the balance sheet. Our main sample selection rule is to consider only those firms with a positive value-added over the period, and with at least 50 employees. Indeed, focusing on medium-large-firms gives us the opportunity to evaluate the redistributive patterns of different firm strategies without excluding the potential effect of internationalization that is more likely diffused among medium-large firms.

Given that at firm-level total labour cost can exceed the amount of total value-added which can be negative especially during an economic crisis, we follow Perugini et al. (2017) and exclude all cases in which the labour share is negative. We then apply trimming at the top and bottom 0.5% of the labour share distribution to obtain a final sample of 6810 firms (i.e. 2410 in 2010 and 4400 in 2015). Though, the sample dimension is higher in 2015 than in 2010 due to the increase in the number of firms interviewed in the RIL 2015 wave with respect to the RIL 2010 wave, both cross-sections are highly representative of the national population of Italian firms in the corresponding year.

The explanatory variables used in our empirical analysis can be grouped in the following three categories: internationalization strategies, technological patterns and institutional settings. Internationalization is captured by variables measuring firm’s involvement in international markets: the share of firm export over total value-added (EXP), whether the firm has realized some direct foreign investments (FDI), whether the firm has outsourced part of its production (OUT), and whether the firm belongs to a foreign group (FG). The extent of firm exposition to technological change (that we call “Technological patterns”) is measured by two binary variables: whether the firm has introduced process (PCI) or product (PDI) innovation in the past three years. Finally, four variables capture institutional determinants of the labour share (“Institutional settings”): the share of workers affiliated to unions (UNION) and the share of temporary workers (TEMP). Further variables are introduced as controls: the educational attainments of managers, the age, sex and occupational distribution of workers within firms, the capital-labour ratio, the Herfindahl index of market power, and a set of dummies for industrial sectors at the two-digit level (NACE Rev.2) and the regions where firms operate (NUTS-3).

4 Heterogeneous patterns of the firm-level labour share: some descriptive evidence

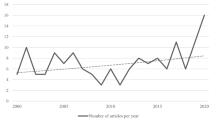

Italy is an interesting case-study as both the country-level and the firm-level labour share remained basically stable between 2010 and 2015 looking at the mean of the distribution only. However, the labour share dispersion has increased over time suggesting the presence of heterogeneous patterns among firms (Fig. 1). Indeed, while the aggregate labour share has not changed or slightly increased, the bottom quartile (25th) decreased, and the top quartile (75th) co-moved with the median and increased as well. This evidence highlights diverging trends in the labour share along its distribution and points to the importance of decomposing the role played by several factors proxying different strategies pursued by firms.

Dissecting the firm-level labour share distribution, we investigate the main features of firms populating different quantiles of the labour share. Firms with a lower labour share register on average both lower labour costs and lower value-added. These firms are also less capital-intensive—showing over time a lower value of capital per employee. Low labour share firms are on average high-productive firms, with higher labour cost per employee. Conversely, the cluster of firms registering a high labour share is composed by less productive firms paying lower wages and being less capital-intensive (see Table 4 in the Appendix). Descriptive evidence reveals the existence of two main groups of firms: those with a lower labour share (high wages and high productivity) and those with a high labour share (low wages and low productivity). This evidence is consistent with other firm-level empirical studies. On French data, Gouin-Bonenfant (2018) documents that low labour share firms are those with both high value-added and paying above average salaries. Moreover, high value-added firms tend to employ more skilled and more productive workers paying them higher wages (Shimer and Smith 2000; Lochner and Schulz 2020).

The existence of huge differences across businesses in terms of wages and productivities allows us to focus on inter-firms’ differences in the allocation of rents. According to the rent-sharing theory, we should expect that more productive firms are more likely to share extra gains with workers (Van Reneen 1996). However, rent sharing has been reverted over the last decade leading more productive firms to be less redistributive (Bell et al. 2019; Card et al. 2018). This pattern emerges from our data as well.

Focusing on the main drivers of the firm-level labour share (Table 1), low labour share firms register on average a lower percentage of union members and a higher share of temporary employees. Indeed, the number of trade union members as a percentage of total employees or as a percentage of total employment, from 2010 to 2015, decreases by 18%, suggesting a potential decrease in the labour share. The decline in union density has often been linked to the weakening of workers’ bargaining power, negatively affecting their ability to negotiate a larger share of productivity growth as labour compensation. The share of firms declaring to introduce product/process innovations is higher among low labour share firms suggesting that in our sample more productive firms are the ones not redistributing gains to workers.

Finally, looking at internationalization strategies, low labour share firms display a higher participation to international trade (on average low labour share firms export about 21% of their value-added), they are part of international groups (17% of low labour share firms is part of foreign groups) and 15% declared to have realized some foreign direct investments. Conversely, high labour share firms export less (around 15% of their value-added) and 5% of firms declares to pursue offshoring strategies. The incidence of different firm strategies changes along the distribution.

Before moving to the econometric analysis, it can be of interest to provide some descriptive evidences of the evolution of the sectoral composition of high, medium and low labour share firms in 2010 and 2015 in order to underline some kind of structural change in the composition of firms by quantiles of labour share. To this aim, Fig. 2 shows that the sectoral composition of firms has changed between 2010 and 2015 with a clear different pattern along the distribution of the labour share. Below the 25th percentile and until the 75th percentile of the distribution, the share of firms in the less knowledge intensive services (LKIS) has decreased over time. Conversely, in the same period, the share of firms in high/med high tech and med-low tech manufacturing has increased. Above the 75th percentile of the labour share we observe a reduction in the share of firms in med-low tech manufacturing. This observed variation in the composition of firms by sector can explain, at least partially, the dynamics of the labour share along the distribution presented in Fig. 1 and highlights the importance of distinguishing between changes in the composition of firms in terms of their characteristics (explained part), and all other non-compositional variations (unexplained part).

Percentage points variation of the sectoral composition of firms by main quantiles of the labour share (2010–2015) (Firms have been grouped according to Eurostat classification in High and Med-high Tech manufacturing, Med-Low Tech manufacturing, Knowledge Intensive Sectors and Less Knowledge Intensive Sectors. For the complete list of sectors, refer to https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/Annexes/htec_esms_an3.pdf).

The increase in the labour share at the top of the distribution is associated with an increasing share of less knowledge intensive firms. These firms, that are the least productive, the lowest-capital-intensive ones and with the lowest wages, have registered over time a faster growth in the labour share compared to high-productive firms where labour share has decreased. High-productive and high-paying firms have redistributed less than low-productive and low-paying firms over 2010–2015.

5 Methodology

To decompose the labour share variations occurred between 2010 and 2015 over the labour share distribution, we firstly estimate the following econometric specification at different percentiles of the labour share distribution by means of Unconditional Quantile Regression (UQR):

where, apart from our regressors of interest described is Sect. 3, \(\mathrm{log}{LS}_{i}\) is the log labour share of firm i; \({\omega }_{s}\) captures a Herfindahl index of market power calculated by considering sales and the 6-digit Ateco classification of industry; \({\upgamma }_{i}\) is the vector of firm-level control variables which includes the log Capital-Labour ratio, the log of the number of employees, occupational shares (e.g. share of managers, share of professionals, share of clerks), share of female employees, a set of dummies for management education (secondary, tertiary), shares of employees by age categories (share 25–34, share 35–49, share over 50); \({Z}_{j}\) is the vector of 2-digit Ateco dummies, \({Y}_{r}\) is the vector of regional dummies, and \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) is the disturbance.

Our empirical analysis is thus implemented in two different steps. Firstly, we estimate Eq. (1) for each of the two repeated cross-sections of RIL (i.e. 2010 and 2015 waves). Since the aim of the paper is to analyze the impact of each set of determinants along the entire labour share distribution, our empirical analysis is developed using UQR. The UQR, alternatively labelled as RIF regression, has been originally proposed by Firpo et al. (2009). It is based on the influence function (IF), a statistical method exploited to evaluate the robustness of any given parameter of a distribution to the presence of outliers (Hampel 1974). The RIF of a given parameter is simply obtained by summing the parameter and the influence function at that parameter.

In the second step of our analysis, we use a detailed decomposition method as the one proposed by Fortin et al. (2011). In detail, we decompose the estimated variation of the labour share occurred between 2010 and 2015 at different quantiles of the distribution using two representative samples of Italian firms observed by year.Footnote 4 The decomposition is thus obtained after estimating by regressing though UQR the labour share on firms’ characteristics for each of the two groups.Footnote 5 More formally, the marginal effect at the \(\theta th\) quantile is obtained by assuming a linear function of the explanatory variables:

Then, a decomposition à la Oaxaca-Blinder is performed to split the total variation in explained and unexplained effects. This means that the labour share variation occurred between 2015 and 2010 can be expressed according to the following expression:

where \({\Delta }_{\theta }\) is the gap in the labour share between the two years considered at the \(\theta th\) quantile and, for each \(\theta th\) quantile, the decomposition takes the following form:

where the total gap between the two groups at the \(\theta th\) quantile is decomposed in an unexplained effect \({\widehat{\Delta }}_{U,\theta }\), which is the effect due to variations, between 2010 and 2015, in the returns of covariates, and in a composition effect \({\widehat{\Delta }}_{E,\theta }\), which is instead related to variations in the distribution of the same covariates between the two years. Additionally, we further decompose the two effects into the contribution of each single covariate to obtain the so-called detailed decomposition.

However, the decomposition extended for different parameters of the distribution can be biased given that the conditional expectation expressed in Eq. (1) holds linearly only (Barsky et al. 2002; Fortin et al. 2011). This is the reason why, according to what suggested by Di Nardo et al. (1996), it is necessary to correct the quantile decomposition by reweighting the distribution of covariates in our baseline period (i.e. 2010) to have the same distribution of covariates in the second period (i.e. 2015). Then, to remove the bias and obtain the “true” explained and unexplained effects, we need to reformulate Eq. (4) in this way:

where the subscript 2015 expressed in parenthesis means that we are estimating specific parameters using the 2010 sample after reweighting the distribution of covariates to have the same distribution of 2015.

The main advantage of using this empirical approach is that, unlike the case in which we use the simple RIF-regression, we can replace the strong strict exogeneity assumption with the weaker ignorability assumption.Footnote 6 The ignorability assumption indeed only requires that the covariance between the vector X and the error term does not vary from group 1 to group 2 (Firpo et al. 2011, 2018). Accordingly, even when a specific regressor is correlated to the error term after controlling for the whole set of other control variables in the two year-specific regressions (i.e. the covariate is endogenous), if endogeneity does not vary from 2010 to 2015 and the ignorability assumption holds, then:

-

we can interpret the unexplained part of the decomposition as the “pure” effect of a given covariate on the labour share;

-

the explained part of the decomposition is related only to changes in the distribution of X.

According to the decomposition method adopted, we expect the coefficients of the unexplained part to be different from the ones obtained by estimating the RIF-regression if our covariates of interest are endogenous even after adding the full set of controls. It is important to note that the ignorability assumption is not a strong assumption in our case given that endogeneity is unlikely to change much in a very short time period after controlling for the rich set of covariates included in our baseline specification. However, we suggest some caution in interpreting the “unexplained” coefficients as the causal effect of a given driver on the log labour share given that we cannot completely control for the presence of some residual time-varying endogeneity.

The detailed unexplained part of decomposition is not easy to interpret due to the choice of the base group which can be often arbitrary. Therefore, since it is problematic to find a base group in the case of continuous covariates, we follow Firpo et al. (2011) and Naticchioni et al. (2014) to normalize all continuous variables included in the regressions as covariates. To do that, we adopt the following transformation:

where \({\sigma }_{{X}_{2010}}\) is the standard deviation of \({X}_{2010}\) and \(E({X}_{2010})\) is its expected value. Though, this kind of normalization does not modify all explained effects, it has a re-scaling effect on all unexplained effects, without affecting the sign of the coefficient.

6 Estimation results

6.1 UQR estimate

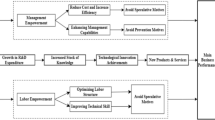

In this section, we firstly discuss the results obtained from the UQR analysis applied on the two representative samples of Italian medium-large firms. As a first step of our econometric approach, we estimate Eq. (1) where the log labour share is regressed on the whole set of firm-level variables. The richness of the RIL database allows us to simultaneously consider a wide range of firm-level characteristics. Following our theoretical framework, in the presentation of the results, we focus on the three main firm drivers at the core of our analysis: internationalization, institutional settings, and technological patterns (Table 2) which are related to the two main firm strategies. These main drivers may be grouped in three categories: those impacting on value-added, those influencing labour costs and, a third transversal type directly affecting bargaining of rents within firms—contractual arrangements and union coverage (see Fig. 3 in the Appendix). Bargaining of rents might occur on productivity gains, or alternatively on labour costs.

Focusing on the variables proxying the international behavior of firms (internationalization), it emerges that, after controlling for several other firms’ characteristics, outsourcing is negatively associated with the labour share mainly in 2015 and among less capital-intensive firms. In addition, firms’ involvement in foreign direct investment (FDI) seems to compress the labour share at the bottom of the labour share distribution—among high-productive firms—, while the realization of FDI does not affect the labour share at the top of the distribution among less productive firms. Being part of a foreign group is positively associated with labour share growth.

Linking these results to our theoretical framework, internalization entails activities that can be productivity-enhancing or based on cost compression. Several empirical studies using firm-level data confirm that imports and offshoring have tended to deteriorate the bargaining power of workers (Dumont et al. 2006). The cost-compression effect of offshoring emerges among low-productive and low capital-intensive firms where the process of bargaining is based on labour costs more than productivity gains. We expect that outsourcing should deteriorate workers bargaining power everywhere, but the effect should be relative more important among labor-intensive firms where workers are more exposed to competition of foreign low-skilled workers.

The relationship between export and productivity cannot be stated a priori, several elements should be accounted such as export destinations, types of exported goods, intensity of export (Blalock and Gertler 2004; Wagner 2007). More productive firms are also more likely than less productive firms to export, therefore we can hypothesize that exporting is to some extent correlated with firm productivity leading firms and workers to bargain on productivity gains more than labour costs. This bargaining leads to a labour share compression along the entire distribution.

Shifting the focus to institutional factors, results highlight that the share of union members is positively associated with the labour share along the entire distribution and both in 2010 and in 2015 in line with previous empirical findings (see for European industries, Damiani et al. 2018 and for US, Young and Zuleta 2018). Union density—measured as number of trade union members as a percentage of total employees or as a percentage of total employment—has often been linked to workers’ bargaining power, affecting their ability to negotiate a larger share of productivity growth as labour compensation (OECD 2015). This institutional factor is likely to affect the whole distribution and to be in place particularly among high-productive firms where there are some gains to be shared.

An increasing share of temporary employees is associated with a decreasing labour share along the entire distribution. Temporary employees are expected on average to have less bargain power with respect to permanent workers. The only exception is among the more productive firms where temporary employment is not associated with wage compression. Empirical literature supports this evidence on heterogeneous usages of temporary employment among high-productive and low-productive firms (Cirillo and Ricci 2020). High-productive firms resort to temporary contracts as “screening device” for more productive workers and tend to convert temporary employment in permanent positions. Conversely, one might hypothesize a sort of “systematic use” of temporary employment by low-productive firms to permanently staff positions and pursuing a strategy of cost compression (Vidal and Tigges 2009).

In terms of technological patterns, it emerges that the introduction of a process innovation is associated with a contraction of the firm-level labour share mainly in 2010. In 2015, this effect only holds for those firms at the top of the distribution. As expected from the literature, the introduction of production innovations might lead to temporary extra-rents subsequently divided between owners and workers improving the functional distribution of income (Van Reenen 1996; Pianta and Tancioni 2008). The advantage of a temporary monopoly position gained by the innovative firm leads to an increase in the labour share that shows up among more capital-intensive and more productive firms. However, this redistributive pattern disappears in 2015.

6.2 Detailed decomposition results

In this section we go one step further by decomposing changes in the labour share occurred between 2010 and 2015 for each of the three previously selected quantiles (i.e. P25, P50 and P75). The detailed decomposition analysis (as formally expressed in Eq. 3) allows to consider variations over time of each of the three channels: internationalization, institutional settings, and technological patterns. Furthermore, the decomposition method allows to distinguish between composition (explained part of the decomposition) and unexplained effects for each selected regressor. Therefore, in Table 3 we show the results of decomposition referred to both explained and the unexplained effects, giving emphasis to the second ones.Footnote 7

Explained effects (Panel A Table 3) capture the relevance of all variations in the distribution of firm characteristics occurred between 2010 and 2015. Significant coefficients (offshoring, temporary employment, share of union members) refer to changes in the composition of each quantile that can affect the labour share over time due to proportion of firms having certain specific characteristics. After controlling for compositional effects, we focus on Panel B of Table 3 illustrating “unexplained effects” that can be intended as the “pure” drivers of the labour share variation (under the ignorability assumption hypothesis) and therefore deserve a peculiar attention.

Results of the unexplained parts of the decomposition shed more light on those drivers more likely to affect the bargaining within firm. We hypothesize that bargaining might occur on productivity gains or on labour costs. Some drivers are likely to directly affect productivity—such as export and innovation—while other—see offshoring—are more likely related to wage compression. All these drivers can lead to a labour share increase/decrease according to the relative growth of value-added with respect to labour costs.

Panel B of Table 3 shows that outsourcing is the prevailing firm-strategy pursued to compress wages among both high-productive and low-productive firms. Besides outsourcing, we find that being part of a foreign group is constantly associated with a higher labour share along the entire distribution, meaning that both high-productive and low-productive firms that are part of foreign group have registered an increase in the labour share over time compared to those firms that do not participate in multinational consortia. Many empirical studies confirm that firms engaged in international markets tend to pay higher wages to their employees (Munch and Skaksen 2008; Schank et al. 2007, 2010). This seems confirmed in our analysis.

The amount of export over total value-added is negatively associated with the labour share for each of the three quantiles considered in our analysis. Although exporting is usually positively associated to productivity (and high-skilled wages), our results show a non-redistributive pattern related to those firms engaged in exporting activities.

Focusing on technological patterns, we observe that, among firms with a lower labour share, the introduction of product innovation strongly decreases the labour share: high-productive firms are not redistributing gains from innovations. Process innovations are associated with the labour share growth at the bottom of the distribution among high-productive firms. The latter are the ones innovating over 2010–2015.

Looking at specific institutional settings hypothesized to affect the whole distribution of firms, we detect that among those firms with a higher labour share, an increase in firm unionization positively affects the labour share; the same effect is due to the share of temporary employees. An increase in the share of workers with temporary work arrangements seems to slightly push up the labour share at least in low-productive firms. This result might be explained by the occupational dynamics registered over 2010–2015 and partly contradict the expectation of lower bargaining power for temporary workers compared to permanent ones (Adrjan 2018).

To sum up, results presented in Table 3 (Panel B) suggest that over 2010–2015 changes in the labour share were mainly driven by outsourcing and export decisions that are related to a lower labour share. Some structural features of firms—such as being part of a multinational consortia—are associated to a higher labour share. Innovation is statistically significant only among firms at the bottom of the labour share distribution (more productive firms). More specifically, product innovation plays a crucial role pushing down the labour share, while process innovation drives up the labour share. Finally, unionization and temporary employment explain increases in the labour share among less productive firms, while they are not significant at the bottom of the distribution.

Firms have several decisions to take in order to be competitive on the labour markets. Some of them are more likely related to value-added growth (realization of FDI, export, product innovation) while others ground on cost competitiveness (process innovation labour-displacing, outsourcing). Labour income share depends on the relative growth of value-added with respect to labour costs. Some drivers affect the whole distribution of firms: exporting and outsourcing are implemented by high-productive and low-productive firms and are related to a reduction in the labour income share. However, while exporting is more likely to affect valued added growth, outsourcing should influence the wage structure of firms. The final effect is a declining labour share.

There are two main drivers that are relevant for a specific set of firms. Product and process innovations only concern highly productive firms and are used in opposite terms: when product innovations are introduced, firms do not redistribute gains, while process innovations do not display a labour-displacing feature.

Finally, institutional settings, that we hypothesize to be transversal along the whole distribution (see Fig. 3 in Appendix A), only apply in low-productive and less capital-intensive firms. In these firms, within-firm bargaining concerns labour costs more than productivity. Unionization pushes up the labour share and avoids compressing the labour cost given that productivity has been almost flat over 2010–2015 for this group of firms.

7 Conclusions

The increase in inequality experienced over the last decades has fueled an intense debate on the main drivers accounting for the distribution of gains within firm. From this perspective, little attention has been given to the functional distribution of income mainly studied at the macro level disregarding the locus of firm where the bargaining of rents occurs. By taking advantage of an original dataset merging the Rilevamento Imprese e Lavoratori (RIL) with AIDA archive, we explore the main drivers of the labour share in the short run. We apply a detailed decomposition method to analyze variations in the labour share occurred in Italy between 2010 and 2015 at three different quantiles of the labour share distribution.

Quantiles of the labour share distribution map heterogeneous firms in terms of average labour productivity, average labour costs and capital intensity. We hypothesize that in heterogeneous firms the bargaining of rents might involve productivity or, alternatively, labour costs.

Our analysis sheds lights on two major points.

First, high-productive and high-paying firms are those registering a lower labour share, while less productive and low-paying firms have a higher labour share. Furthermore, the labour share of high-productive and high-paying firms has decreased on average over time, while in low-productive firms the labour share has increased. Our analysis shows that more productive and more capital-intensive firms (at the bottom of the labour share distribution) have been poorly redistributive over 2010–2015 pointing out a decoupling of wages from productivity.

Second, after taking into account the specificities of high and low labour share firms, we explore how several firm characteristics such as internationalization, institutional settings and technological patterns affect firm-level labour share. Controlling for composition effects, the decomposition exercise shows that outsourcing is the main factor which contributes to contract the labour share and this result holds along the entire distribution. Conversely, the participation to an international group is associated with a higher labour share. Focusing on firm institutional policies, a major role is played by unionization—at least among firms with a higher labour share. Unions are positively correlated to the labour share at the 75th percentile.

Technological patterns are relevant at the bottom of the labour share distribution among high-productive firms. More specifically, our results show that product innovation is strongly and negative correlated to the labour share, while the introduction of process innovation being labour intensive might lead to an increase in the labour share among high-productive firms.

Indeed, a further improvement of the analysis would be to analyze a longer time span allowing us to shed lights on long-term structural factors impacting on the firm labour share and consequently on how rents (or productivity gains) are shared within-firm. In this paper, we specifically focus on the 2010–2015 period when more productive and more innovative firms were particularly hit by the crisis and therefore, they register a slower redistributive pattern. From this perspective, the analysis of a longer time span would allow to capture structural elements related to redistributive features of firms. Given that, this analysis clearly highlights that outsourcing is the main relevant factor which exerts a downward pressure on the labour share (through wages). Therefore, policies facilitating firms’ offshoring strategies may be detrimental for income distribution.

To conclude, it is worth noting that, although the results obtained in this paper cannot be easily extended to other high-income countries because they reflect the Italian specific context, our methodology can be easily applied to other country-specific studies to tackle composition effects in the analysis of firm-level labour income share.

Notes

Since we focus on a single country, we are able to isolate the effects of globalization on the labour share more clearly, in order to avoid, by construction, potential problems that emerge from the complex interactions between a variety of labour market institutions and openness that Rodrik (1998) and Agell (1999) have pointed out.

Firms move in a context of deep uncertainty and they operate in not fully competitive markets (see Teece 2019 on this point).

Figure 3 in Appendix provides a graphical illustration of our hypotheses.

Although some of the firms in the sample are observed in both years, our methodology only requires that the parameters of the sample distribution of the labour share are representative of the parameters of the true distribution of the labour share in each year, despite the fact that the dataset is partially panel. As in our case, many previous studies which analyse distributional dynamics and adopt a similar decomposition method use two or more repeated cross-sections and partially panel datasets (see Fortin and Lemieux 2016; Firpo et al. 2018).

In the first group we have the labour share computed at the firm level and firms’ characteristics observed in 2010 and, in the second group, the labour share and the same set of firms’ characteristics observed in 2015).

Note that when panel datasets are available, a fixed-effects estimator is consistent only if the conditional strict exogeneity assumption hold. Accordingly, the time-varying component of the error term should be uncorrelated with any regressor of interest. On the contrary, under the ignorability assumption we only need that the degree of correlation between the regressor of interest and any potential time-varying omitted variable does not vary over time to consistently distinguish between explained and unexplained effects.

References

Adrjan, P. (2018). The mightier, the stingier. Firms’ market power, capital intensity, and the labor share of income. MPRA Paper 83925, Munich, University Library of Munich.

Agell, J. (1999). On the benefits from rigid labour markets: Norms, market failures, and social insurance. The Economic Journal, 109, F143–F164.

Alvarez-Cuadrado, F., Van Long, N., & Poschke, M. (2018). Capital-labor substitution, structural change and the labor income share. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 87, 206–231.

Arpaia, A., Boza, E. P., & Pichelmann, K. (2009). Understanding labour income share dynamics in Europe. Economic Papers, 379, 1–51.

Atkinson, B. (2009). Factor shares: The principal problem of political economy? Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 25(1), 3–16.

Autor, H., & Dorn, D. (2013). The growth of low skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553–1597.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2020). The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 645–709.

Azmat, G., Manning, G., & Van Reenen, J. (2012). Privatization and the decline of labor’s share. International evidence from network industries. Economica, 79(315), 470–492.

Barkai, S. (2020). Declining labor and capital shares. Journal of Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12909.

Barsky, R., Bound, J., Charles, K. K., & Lupton, J. P. (2002). Accounting for the black–white wealth gap. A nonparametric approach. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 97(459), 663–673.

Barth, E., Bryson, A., Davis, J. C., & Freeman, R. (2016). It’s where you work: Increases in the dispersion of earnings across establishments and individuals in the United States. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S2), S67–S97.

Bell, B. D., & Van Reenen, J. (2013). Extreme wage inequality. Pay at the very top. American Economic Review, 103(3), 153–157.

Bell, B., Bukowski, P., & Machin, S. (2019). Rent sharing and inclusive growth (Vol. 101868). London: London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library.

Bentolila, S., & Saint-Paul, G. (2003). Explaining movements in the labor share. The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, 3(1), 1–33.

Berman, E., Bound, J., & Griliches, Z. (1994). Changes in the demand for skilled labor within US manufacturing evidence from the annual survey of manufactures. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(2), 367–397.

Biewen, M., & Seckler, M. (2019). Unions, internationalization, tasks, firms, and worker characteristics: A detailed decomposition analysis of rising wage inequality in Germany. Journal of Economic Inequality, 17(4), 461–498.

BIS (Bank for International Settlements) (2006). 76th Annual Report, Basel.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2004). Learning from exporting revisited in a less developed setting. Journal of Development Economics, 75(2), 397–416.

Böckerman, P., & Maliranta, M. (2012). Globalization, creative destruction, and labour share change: Evidence on the determinants and mechanisms from longitudinal plant-level data. Oxford Economic Papers, 64(2), 259–280.

Bogliacino, F., & Maestri, V. (2014). Increasing economic inequalities? In S. Wiemer, B. Nolan, D. Checchi, I. Marx, A. McKnight, I. G. Tóth, & H. van de Werfhorst (Eds.), Changing inequalities in rich countries. Analytical and comparative perspectives (pp. 15–48). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bogliacino, F., Guarascio, D., & Cirillo, V. (2017). The dynamics of profits and wages. Technology, offshoring and demand. Industry and Innovation, 25(8), 778–808.

Bugamelli, M., Lotti, F., Amici, M., Ciapanna, E., Colonna, F., D’Amuri, F., Scoccianti, F., et al. (2018). Productivity growth in Italy: A tale of a slow motion change. Bank of Italy Occasional Paper (Vol. 422).

Burke, J., & Epstein, G. (2001). Threat effects and the internationalization of production. PERI Working Papers, p. 29.

Card, D., Cardoso, A. R., Heining, J., & Kline, P. (2018). Firms and labor market inequality: Evidence and some theory. Journal of Labor Economics, 36(S1), S13–S70.

Checchi, D., & García-Peñalosa, C. (2010). Labor market institutions and the personal distribution of income in the OECD. Economica, 77(307), 413–450.

Chirinko, R. S. (2008). σ: The long and short of it. Journal of Macroeconomics, 30(2), 671–686.

Ciarli T., Marzucchi A., Salgado E., & Savona M. (2018). The effect of R&D growth on employment and self-employment in local labor markets. SWPS 2018-08. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3147861.

Cirillo, V., & Ricci, A. (2020). Heterogeneity matters: temporary employment, productivity and wages in Italian firms. Econ Polit. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00197-2.

D’Elia, E., & Gabriele, S. (2019). Labour and capital remuneration in the OECD countries. Working Papers LuissLab, 19146, Dipartimento di Economia e Finanza, LUISS Guido Carli.

Damiani, M., Pompei, F., & Ricci, A. (2018). Labour share, employment protection, and unions in European Economies. Socio-Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy025.

De Serres, A., Scarpetta, S., & De La Maisonneuve, C. (2001). Falling wage shares in Europe and the United States. How important is aggregation bias? Empirica, 28(4), 375–401.

Di Nardo, J., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (1996). Labor Market Institutions and the distribution of wages, 1973–1992. A Semiparametric Approach. Econometrica, 64(5), 1001–1044.

Dumont, M., Rayp, G., & Willeme, P. (2006). Does internationalization affect union bargaining power? An empirical study for five EU countries. Oxford Economic Papers, 58(1), 77–102.

Dünhaupt, P. (2013). Determinants of functional income distribution: Theory and empirical evidence. Global Labour University Working Paper 18.

E Commission,Employment in Europe. (2007). The labor income share in the European Union. Luxembourg: Office for Offical Publications of the European Communities.

Elsby, M. W., Hobijn, B., & Şahin, A. (2013). The decline of the US labor share. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2013(2), 1–63.

Firpo, S., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2009). Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica, 77(3), 953–973.

Firpo, S., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2011). Occupational tasks and changes in the wage structure (Vol. 5542). Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Firpo, S., Fortin, N., & Lemieux, T. (2018). Decomposing wage distributions using recentered influence function regressions. Econometrics, 6(28), 1–40.

Fortin, N., & Lemieux, T. (2016). Inequality and changes in task prices: Within and between occupation effects. Research in Labor Economics, 43, 195–226.

Fortin, N., Lemieux, T., & Firpo, S. (2011). Decomposition methods in economics. Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, pp. 1–102). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

García-Peñalosa, C. (2010). Income distribution, economic growth and European integration. Journal of Economic Inequality, 8(3), 277–292.

Glyn, A. (2009). Functional distribution and income inequality. In B. Nolan, W. Salverda, & T. M. Smeeding (Eds.), Handbook of economic inequality (pp. 101–126). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gollin, D. (2002). Getting income shares right. Journal of Political Economy, 110(2), 458–474.

Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2014). Explaining job polarization. Routine-biased technological change and offshoring. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2509–2526.

Gouin-Bonenfant, E. (2018). Productivity dispersion, between-firm competition, and the labor share. In Society for Economic Dynamics. Meeting Papers (Vol. 1171).

Growiec, J. (2012). Determinants of the labor share. Evidence from a panel of firms. Eastern European Economics, 50(5), 23–65.

Guarascio, D., & Pianta, M. (2017). The gains from technology: New products, exports and profits. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 26(8), 779–804.

Guellec, D., & Paunov, C. (2017). Digital innovation and the distribution of income. NBER Working Paper, (w23987).

Guerriero, M., & Sen, K. (2012). What determines the share of labour in national income? A cross-country analysis (Vol. 6643). Bonn: Institute of Labor Economics (IZA).

Guschanski, A., & Onaran, Ö. (2018). The labour share and financialisation: Evidence from publicly listed firms (Vol. 19371). London: University of Greenwich, Greenwich Political Economy Research Centre.

Hampel, F. R. (1974). The influence curve and its role in robust estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 69(346), 383–393.

Hicks, J. (1963). The theory of wages. Palgrave Macmillan, UK.

Hogrefe, J., & Kappler, M. (2013). The labor share of income: Heterogeneous causes for parallel movements? Journal of Economic Inequality, 11(3), 303–319.

Hutchinson, J., & Persyn, D. (2012). Globalisation, concentration and footloose firms: In search of the main cause of the declining labor share. Review of World Economics, 148(1), 17–43.

IMF. (2007). World economic outlook. Washington DC: IMF.

International Labour Office (ILO) (2008). Global Wage Report 2008/09: Minimum wages and collective bargaining. Towards policy coherence (Geneva).

Karabarbounis, L., & Neiman, B. (2014). The global decline of the labor share. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 61–103.

Landini, F., Arrighetti, A., & Bartoloni, E. (2020). The sources of heterogeneity in firm performance: Lessons from Italy. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 44(3), 527–558.

Lawrence, R. Z. (2015). Recent declines in labor's share in Us income: A preliminary neoclassical account. NBER Working Paper, (w21296).

Lochner, B. & Schulz, B. (2020). Firm productivity, wages and sorting. IAB Discussion Paper, 202004. Institute for Employment Research, Nuremberg, Germany.

Munch, J. R., & Skaksen, J. R. (2008). Human capital and wages in exporting firms. Journal of International Economics, 75, 363–372.

Naticchioni, P., Ragusa, G., & Massari, R. (2014). Unconditional and conditional wage polarization in Europe (Vol. 8465). Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Oberfield, E., & Raval, D. (2014). Micro data and macro technology. NBER Working Paper, (w20452).

OECD. (2008). Growing unequal. Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2011). Divided we stand. Why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012). Labor losing to capital. What explains the declining labor share? OECD employment outlook 2012 (pp. 109–161). Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2015). The labour share in G20 economies. Report prepared for the G20 Employment Working Group, Antalya, Turkey. https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/employment-and-social-policy/The-Labour-Share-in-G20-Economies.pdf.

Pereira, J. M., & Galego, A. (2019). Diverging trends of wage inequality in Europe. Oxford Economic Papers, 71(4), 799–823.

Perugini, C., Vecchi, M., & Venturini, F. (2017). Globalisation and the decline of the labor share. A microeconomic perspective. Economic System, 41(4), 524–536.

Pianta, M., & Tancioni, M. (2008). Innovations, wages, and profits. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 31(1), 101–123.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rodrik, D. (1998). Has globalization gone too far? Challenge, 41(2), 81–94.

Schank, T., Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2007). Do exporters really pay higher wages? First evidence from German linked employer–employee data. Journal of International Economics, 72(1), 52–74.

Schank, T., Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2010). Higher wages in exporting firms: Self-selection, export effect, or both? First evidence from linked employer–employee data. Review of World Economics, 146(2), 303–322.

Schlenker, E., & Schmid, K. D. (2015). Capital income shares and income inequality in 16 EU member countries. Empirica, 42(2), 241–268.

Schwellnus, C., Pak, M., Pionnier, P. A., & Crivellaro, E. (2018). labour share developments over the past two decades: The role of technological progress, globalisation and. winner-takes-most “Dynamics”. OECD Economics Department Working Papers (1503).

Shimer, R., & Smith, L. (2000). Assortative matching and search. Econometrica, 68(2), 343–369.

Siegenthaler, M., & Stucki, T. (2014). Dividing the pie: The determinants of labors share of income on the firm level (No. 14-352). Zurich: KOF Swiss Economic Institute, ETH Zurich.

Solow, R. M. (1958). A skeptical note on the constancy of relative shares. American Economic Review, 48(4), 618–631.

Stansbury, A., & Summers, L. (2020). The declining worker power hypothesis: An explanation for the recent evolution of the american economy. NBER Working Paper (w27193).

Stockhammer, E. (2013). Financialization, income distribution and the crisis. In F. Fadda & P. Tridico (Eds.), Financial crisis, labor markets and institutions (pp. 98–120). New York: Routledge.

Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity? Journal of Economic literature, 49(2), 326–365.

Teece, D. J. (2019). A capability theory of the firm: An economics and (strategic) management perspective. New Zealand Economic Papers, 53(1), 1–43.

Torrini, R. (2016). Labour, profit and housing rent shares in Italian GDP: Long-run trends and recent patterns. Bank of Italy Occasional Paper (318).

Van Reenen, J. (1996). The creation and capture of rents. Wages and innovation in a panel of UK companies. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(1), 195–226.

Vidal, M., & Tigges, L. M. (2009). Temporary employment and strategic staffing in the manufacturing sector. Industrial Relations A Journal of Economy and Society, 48(1), 55–72.

Vivarelli, M. (1995). The economics of technology and employment (p. 458). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Vivarelli, M., & Pianta, M. (Eds.). (2000). The employment impact of innovation: Evidence and policy (pp. 1–216). London: Routledge.

Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm-level data. World Economy, 30(1), 60–82.