Abstract

We employ Italian administrative data to analyze the differentials in wages and workplace injuries between immigrants and natives over the 1994–2012 period. Via propensity score reweighting, we construct the factual and counterfactual, marginal and joint distributions of wages and workplace injuries. Examining the differentials along the entire distributions, our approach yields novel insights on their potential drivers. Our findings confirm that immigrants face lower wages and a substantially higher injury risk than natives; futhermore, they highlight that foreign-born workers display a disproportionate concentration of injuries around the minimum contractual wages. Our results show that the latter can be interpreted as an unintended effect of minimum contractual wages. Indeed, if wages are downward rigid and workplace safety investments are costly, firms employing low-wage workers may reallocate their savings away from wages onto safety. Over time, the gap is found to shrink. Our analysis suggests that, beyond the reduction in workplace intensity during recessions, this may be due to destruction of marginal jobs. Being disproportionally concentrated in marginal occupations, then, lower-skilled migrant workers are more vulnerable to downturns in the economic cycle. Overall, our results highlight that labour market segmentation may co-exist with wage regulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Comparing the working conditions of native and migrant workers is a task that has captured the attention of media reports, official statistics and of a multidisciplinary scholarly literature in different countries. Typically, indeed, foreign workers are involved in jobs that are remunerated less and that are riskier than the natives’ (Orrenius and Zavodny 2013). Their willingness to accept jobs that natives reject is actually an assumption underlying any analysis of the impact of foreign workers on the host country’s labour market (e.g., Hamermesh 1999a; Battisti et al. 2017). If, in addition, foreigners face an entirely different wage offer curve than natives and do not receive adequate compensation for their risk, labor market segmentation (in the sense of Hersch and Viscusi 2010) may emerge (Orrenius and Zavodny 2013). A fundamental implication of this literature, originally noted by Hamermesh (1997) and still understudied, is that, in presence of a binding minimum wage, immigrants’ tolerance of worse working conditions will affect a range of job amenities, primarily workplace safety. The trade-off between safety and wage (Hamermesh 1999a, b; Boone and van Ours 2006) would cause wage floors to have unintended adverse implications for safety (coherently with the results in Hashimoto 1982; Leombruni et al. 2013; Cockx and Ghirelli 2016). Such adverse implications, in turn, may become worse in times of recession.

The presence of wage rigidities may thus complicate the analysis of the overall wellbeing of migrants and the evaluation of equality when investigating native-migrants differentials in labor outcomes. This paper employs an administrative dataset on the Italian labor market to analyze the joint distribution of wages and injuries and to investigate differentials between native and foreign born male workers. The peculiarity of the Italian labor market offers an opportunity for a comprehensive evaluation of the equality in labor market conditions, when job amenities, such as workplace safety, can be traded in exchange of pecuniary characteristics such as wage. Indeed, in presence of a binding minimum contractual wage, the labour cost savings that firms would enjoy by lower remunerations may be transferred onto safety savings. In this sense, minimum contractual wages allow us to study the emergence of such effects that would otherwise be due to unobserved characteristics of the firms and of their workers.

Our study shows that, first of all, foreign workers face lower wages and greater injury risk than natives. Within both groups, lower wage workers face a disproportionately higher injury risk. Moreover, foreigners’ injury risk greatly exceeds that of natives by the same level of wage. In order to identify the extent to which these different distributions are attributable to observable characteristics (e.g. demographic characteristics, sectors of occupation), we build counterfactual distributions by propensity score reweighting (DiNardo et al. 1996). A substantial excess in immigrants’ injury risk by the same level of wages remains that cannot be attributed to observable characteristics.

Studying the changes in the concentration of injuries over time and along the wage distribution, we show that in all sub-periods, the magnitude of the unexplained difference in workplace risk displays a peak at the level of the union wage floor threshold, which in Italy is set by collective bargaining, and remains significant even by higher wage levels. Intriguingly, the gap reduces over time and especially during the economic crisis. Our analysis of the joint distribution suggests that immigrants represent marginal workers, whose jobs are more likely to disappear as the macroeconomic conditions deteriorate . This evidence is consistent with a hedonic model of a dual labor market, where downward pressures on wages are mitigated by minimum contractual wage floors and are transferred to workplace safety. Although the standard problem of hedonic models does not allow us to quantify how much of these unobserved effect are due to lower firms’ or workers’ productivity or to some form of discrimination, our analysis clearly emphasizes that immigrants’ health conditions depend on their marginal and weaker position inside the labor market.

Our empirical analysis shows that an unequal allocation of injury risk and marginality of occupations may occur even in a context characterized by collective bargaining and downward wage rigidity. These dimensions of inequality and of labor market segmentation would have remained undetected, had the analysis focused solely on wages. The paper, thus, contributes to the recent debate on the effect of migration on natives’ labor outcomes by showing that foreign-born workers do not compete for the same job as natives, and may actually substitute for them in unpleasant occupations thus relieving their burden of workplace risks (e.g. Giuntella and Mazzonna 2015; Giuntella et al. 2016).

Additionally, the main message of our findings is that the observed patterns in the differentials in injury rates can be explained by a combination of unobserved characteristics with rigidities in the labor market and that these regulations may contribute to make the employment of marginal workers, most probably lower-skilled migrant workers, more volatile and subject to the cycle.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents our theoretical framework, grounded in the hedonic wage model. Section 3 introduces our methodological approach and our data. Section 4 illustrates the results; Sect. 5 discusses the main findings; and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Theoretical framework

Standard economic theory predicts that risk-averse workers will claim higher wages for riskier jobs (Rosen 1987). However, several factors may lead to a segmentation such that labor markets clear with immigrant workers being forced to accept lower wages by less secure working conditions, effectively receiving little or no compensation for their risk (Viscusi and Hersch 2001; Hersch and Viscusi 2010; Orrenius and Zavodny 2013).

The extant labor economics literature has mainly focused on wage gaps. Yet, a few notable economic works (e.g. Hamermesh 1997; Bauer et al. 1998; Hersch and Viscusi 2010; Orrenius and Zavodny 2013; Dávila et al. 2011), along with a wide epidemiological literature, have sought to measure the unequal access of foreign workers to safety, viewed as a job amenity. Orrenius and Zavodny (2009, 2013) show that, in most countries, foreign workers are overrepresented in occupations and industries with greater injury risk. Other studies (e.g. Giuntella and Mazzonna 2015; Giuntella et al. 2016) suggest that immigrants substitute for native workers in unpleasant occupations and that this reallocation may relieve their burden of workplace risks. Whether this translates in ceteris paribus greater injury and fatality rates for foreigners than for natives (as found by Orrenius and Zavodny 2009; Salminen 2009; Ahonen and Benavides 2006; Bena and Giraudo 2014) is an empirical issue which is heavily affected by the availability of data and by the empirical specification applied.

The mechanisms that determine the equilibrium levels of wages and workplace safety can be explained in the framework of the hedonic wage models (Ehrenberg and Smith 2016; Rosen 1974), represented graphically in the upper-left panel of Fig. 1.

The hedonic model assumes that workers maximize their expected utility, which is a function of wages and of other workplace amenities. From among the set of possible workplace amenities, we consider workplace safety. The curves refer to natives (N) and foreigners (F) with homogeneous characteristics (e.g. industry, occupation, age, etc.), for instance young blue collar workers in the manufacturing sector. Employees’ wages and workplace safety investments represent costs to the employer; hence, bundles with lower wages and less safety represent greater profits for the firm. However, the curves are upward sloped because a higher level of disamenity (i.e. risk) must be compensated by a higher salary. The resulting isoprofits are represented as straight lines for simplicity and are drawn for the two types of workers, assumed to have the same observable characteristics: natives (\(\Pi (w_N,R_N)\)) and foreigners (\(\Pi (w_F,R_F)\)). The intercepts of the isoprofit lines are \(\xi _N\) for the natives and \(\xi _F\) for the foreigners. Although they refer to the same job and the same sector for workers with similar characteristics (e.g. age, education, tenure, firm size), the two intercepts may differ. Possible reasons include: lower productivity of foreigners as workers (e.g. less education, less language proficiency, etc.) and of the firms that hire them; assignment to more dangerous tasks (unobserved) within the same occupation and sector, or less risk-aware behaviour by the worker; taste-based discrimination; monopsonistic discrimination; less unobserved safety investments of firms that hire foreigners; and, as we will see more in detail later, the economic cycle, if foreign workers are allocated to tasks which are more subject to cyclical variation in working efforts. With such a segmentation, migrants will face lower isoprofit curves.

If workplace safety is a normal good, workers may want to trade off part of their earnings for greater safety and sort into safer occupations. But a range of factors may limit immigrants’ ability to claim a compensation for their risk or to trade wage for safety, in which case their isoprofit curves will also be flatter than the natives’ (Hersch and Viscusi 2010; Orrenius and Zavodny 2013). Inferior language proficiency, bureaucratic difficulties in the recognition of their skills, conditionalities in the attribution of the residence permit, weaker social networks and trade union integration (Orrenius and Zavodny 2013) reduce immigrants’ outside options and make their labor supply less elastic to wage and more likely to suffer from monopsonistic discrimination. This type of discrimination may also originate from differences in immigrants’ reservation wages (Manning 2003; Amior 2017), and in preferences over non-wage attributes (Bhaskar and To 1999; Booth and Coles 2007). The heterogeneity in these attributes could affect the overall quality, i.e. including safety conditions, of the jobs offered to foreign workers.

\(U(w_N,R_N)\) and \(U(w_F,R_F)\) represent the indifference curves of natives and foreigners, respectively. Obviously, the worker gets more utility the closer her indifference curve gets to the top-left corner, i.e. by higher salary and lower injury risk.Footnote 1 In equilibrium, by virtue of their higher intercepts, natives will enjoy more safety and higher wages than foreigners.

In the upper right panel of Fig. 1, we introduce the wage floor. In absence of policy constraints, given a range of unobserved characteristics of the worker and of the employer (including discriminatory attitudes), suppose the equilibrium on the immigrants’ labor market corresponds to the wage-safety bundle A, which is located below the corresponding wage floor threshold set by collective bargaining. To comply with the contractual wage floor, firms would have to climb the isoprofit curve up to point A’. This would configure a corner solution located on a lower indifference curve for the foreign worker, by which salary is higher (\(w'_F\)) but at the cost of an increased occupational risk (\(R'_{F}\)). To restore the unrestricted level of safety \(R_F\), an exogenous shock should affect the isoprofit curve and increase the intercepts up to a level where the new isoprofit crosses the union wage floor level at \(R_F\). This could occur if macroeconomic conditions improve, if policy changes intervene, if the employer removes any discriminatory attitudes, or if the foreign worker’s human capital, experience or bargaining power increase radically; however, the foreign worker’s capacity to affect these processes may be very limited.

If, on the contrary, the economic conjuncture worsens, the level of occupational risk in a segmented labor market may ceteris paribus become unbearable in presence of a binding wage floor. In the bottom panel of Fig. 1 we address this issue. Assume there are two states of the economy: good (G) and bad (B). State (G) corresponds to the situation depicted in the upper-right panel; when the economy is in a bad state (B), by the same level of risk, firms are willing to pay lower salaries (or, conversely, by the same level of salaries, are less able to invest in safety). This implies that the isoprofit curves in state \(\Pi _B\) will be lower. To comply with the union wage floor, the firm will have to offer the same minimum salary it was offering in state G, but the corresponding occupational risk will be even higher (\(R'_{F,B}\)). If the firm runs substantial losses during the downturn, the isoprofit curve may move so low that no bearable level of risk would be compatible with the wage floor. Hence, the employer will find it preferable to lay off the foreign worker.

Indeed, recent studies show that the labor outcomes (mainly unemployment, employment, wages) of foreign workers are more sensitive than the natives’ to fluctuations in the economic cycle (e.g., Dustmann et al. 2010; Orrenius and Zavodny 2010). This occurs because immigrant workers are disproportionately more frequently offered precarious contracts. More generally, employers may consider immigrants a risky investment and they may tend to evaluate their productivity in the short rather than in the longer run. Consequently they may consider unprofitable to invest in their training, including safety training. Hence, it is reasonable to expect that migrants are more vulnerable to downturns, since in a rigid labor market, an employer facing cost-saving pressures will tend to dismiss the less protected workers first.

Empirically, this could translate into two opposing effects: (a) if the binding effect of the wage floor prevails on the incentives to dismiss, we should observe a persistence or even an increase in the wage and injury gaps between foreign and natives; (b) if the effect of the downturn is mainly in terms of destroying the jobs of the foreign workers, the observed gap should narrow down. The latter would support the interpretation that immigrant workers are actually marginal workers and that their employment results from a corner solution.

Biddle and Hamermesh (2013), in the US context, find that downturns tend to increase the wage gaps between women and men but to decrease the gaps between African–Americans and whites, due, according to them, to composition effects due to job changes. If there is a trade-off between wage and safety, however, an exclusive focus on wages may miss part of the picture. Hence, we include the role of workplace safety to the analysis and study the relationship of wages and injuries along their joint distribution.

3 Methodology

In order to analyze the different components of the wage and injury gap, we employ the decomposition introduced by DiNardo et al. (1996) (hereinafter DFL decomposition) and its application to discrete data (Biewen 2001). This methodology allows us creating a counterfactual immigrant population which is employed in the same sectors, with the same occupation, contracts, age, tenure and gender profile as the observed immigrant population, but is paid according to the wage schedule of the natives (or faces an injury risk comparable to those of natives, cfr. DiNardo et al. 1996). Hence, we distinguish the effect of the workers’ characteristics on injury and wages from the effect of the remuneration of the workers’ characteristics along the whole wage and injury distributions.

The DFL decomposition is implemented by computing the propensity scores to be an immigrant and to be a native based on a set of characteristics, and by reweighting each observation in the native subsample by the ratio of the two (Hirano et al. 2003). The weights are included in a kernel density function applied to the observations of the natives. In this reweighed distribution, those natives who are more similar to immigrants are weighted more; hence, analysing injury rates and wages of this distribution gives a measure of what wages and injury rates natives would display if they had the same characteristics as the immigrants.

We prefer this approach to methodologies based on differences in means (i.e. Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition) or quantile regressions where wages are analyzed conditional on injuries. As discussed by DiNardo (2002) and Brunell and DiNardo (2004), the Oaxaca–Blinder approach can itself be viewed as a reweighting technique yielding estimates of a reweighted mean; conversely, the DFL approach can be viewed as a generalisation of the Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition. The Oaxaca–Blinder and the DFL decomposition yield very similar results, which are numerically equivalent when the set of covariates is composed entirely by categorical variables. From this point of view, the advantage of the DFL decomposition is to yield estimates of the entire reweighted distribution rather than just of the mean. Moreover, the nature of our key variable of interest, i.e. injuries, which are rare events, constrains our ability to run quantile regressions. As the distribution of workplace accidents is characterized by a large mass of zeros (about 96%, which becomes even larger when considering severe injuries), most quantiles would be equal to zero, so this regression would not be particularly informative. More generally, a regression of wage on injuries, conditional on all available workers’ and job characteristics, would lead to the estimation of a negative coefficient due to the ability bias determined by the unobserved characteristics of native and migrants (i.e. differences in the intercepts shown in Fig. 1, see, e.g. Hamermesh 1999a). We believe that the comparison of the real distributions with the counterfactual ones is more informative on the effects of unobservables on the (joint) distribution of wages and injuries.

As shown by Barsky et al. (2002), DiNardo (2002) and Brunell and DiNardo (2004), the DFL approach is equivalent to viewing the immigration status as a “treatment” and to analyze the effect of being an immigrant on the distribution of wages and injuries under a “selection on observables” set of assumptions (e.g. Heckman et al. 1997).

More formally, in the DFL framework, we can write the density of an outcome variable y (the wage density, or the distribution of injuries) as a function of the immigration status T, where \(T=1\) if the person is an immigrant and \(T=0\) if the person is not an immigrant, and of a set of characteristics z (see DiNardo 2002; Brunell and DiNardo 2004). This derives from the definition of conditional probabilities:

In our case, \(f(y|T=1)\) is either the wage density or the injury density that applies to immigrant workers. We treat injury density as a continuous variable because we measure injuries as a ratio of total injuries to total leave-adjusted full-time equivalent person-years worked in a given cell of homogeneous characteristics. \(f(y|T=0)\) is the corresponding density that applies to non-immigrant workers. As in the DFL approach, the counterfactual distribution of y that would prevail if natives had the same distribution of characteristics as immigrants, can be written as a reweighted distribution of the observed density of natives:Footnote 2

The weights \(w_z\) are defined as the ratio of the density of characteristic z in the two subsamples. They can be seen as the ratio of the probability to observe a given characteristic (or combination of characteristics) among immigrants to the probability to observe it among natives. This way of seeing it allows a convenient simplification:

where the second equality derives from applying the Bayes’ law. While estimation of h(z|T) is hampered by a dimensionality problem, the conditional probability of being an immigrant given z can be estimated by binary choice models such as logit or probit; \(P_0\) and \(P_1\) correspond respectively to the share of natives and the shares of immigrants in the sample.Footnote 3 Essentially, \(w_z\) give more weight to native individuals who display characteristics that are more similar to the immigrants’. Plugging the weights into a kernel density function allows estimating the counterfactual densities of y at each point \(y_t\):

where h is the bandwidth and K is a kernel function—the gaussian in our application as well as in DiNardo et al. (1996). The reweighting procedure allows constructing a fictitious immigrant population which is employed in the same sectors, with the same occupation, age, tenure and gender profile as the observed immigrant population, but is paid according to the wage schedule of the natives (or has a risk propensity comparable to that of natives) (cfr. DiNardo et al. 1996). This procedure can be straightforwardly extended to construct the counterfactual concentration curves for injuries and wages (as in Razzolini et al. 2014), as well as the counterfactual joint distribution of wages and injuries.

The choice of the characteristics z which we use to estimate the propensity scores is largely data driven (see Sect. 3.1): as regards the work relationship, we include firm size, firm age, 18 sectoral dummies, region of work, and type of contract; as regards the individual, we include age, gender, qualification, tenure, and, for the years where the information is available, and a binary variable equal to 1 if the person received family allowances.

The differences between the observed and the counterfactual distributions of natives give a measure of the gaps due to the difference in characteristics; the differences between the counterfactual and the observed distribution of foreigners give a measure of the “unexplained” or “residual” difference (see DiNardo et al. 1996; Biewen 2001; Barsky et al. 2002, for a more formal discussion).

A limitation of this approach is that it does not allow disentangling systematic differences between the natives and the immigrants which are due to observable characteristics that are an exclusive attribute of immigrants—for example, language difficulties—from more subtle differences due, for example, to discrimination. Yet, the dynamics of both the “explained” and “residual” component can be studied and yield useful descriptive insights.

Related to this, the composition of immigrants may affect the results.Footnote 4 An important distinction must be made in this regard. To the extent that compositional effects can be captured by observable characteristics, they do not pose a problem to our analysis; they do, instead, if changes in the composition drive changes in unobservable characteristics. In Appendix section “Compositional effects”, we carefully scrutinise this possibility. Our results show that, while the composition of immigrants by country of origin changes significantly over time, this does not seem to be the main driver of the dynamics in the gaps in injury rates and wages, which is reassuring with respect to the validity of our analysis.

Similarly to the common support condition that is required for the validity of propensity score matching (Caliendo and Kopeinig 2008), our approach requires that the individuals in our treated and control groups are compared over a range of comparable characteristics. Failing to ensure common support would in our case result in extremely large or extremely low weights. To avoid extremely large weights, we discarded the observations for which \({\hat{P}}(T=1|z)<min[{\hat{P}}(T=0|z)]\) (cfr. Dehejia and Wahba 2002), which typically implied dropping a negligible number of observations every year. Moreover, to mitigate unobserved heterogeneity, we focus our analysis of the joint distribution of injuries and wages on the subsample of male, blue-collar workers operating in the manufacturing sector.

Our factual group is composed of all migrants from “high migration pressure” (HMP) countries—we refer to them as “foreigners” or “immigrants” throughout our discussion; the corresponding “unfactual” group is composed of workers born in Italy and in advanced development countries—which we throughout refer to as “natives” for simplicity.Footnote 5

To analyse the relationship between injuries and wages, we first analyse wage gaps and injury gaps separately, then we use the observed and counterfactual subsamples to compute wage deciles and the injury rates in each decile (in Appendix section “Concentration curves” we also study concentration curves in the observed and counterfactual subsamples; see Wagstaff et al. 1991; Kakwani et al. 1997).Footnote 6

3.1 Data

We use administrative data deriving from the linkage of the Work Histories Italian Panel (WHIP), a 1:15 sample of the Italian social security data, with administrative records from the Italian Workers’ Compensation Authority (INAIL) for 1994–2012 (Bena et al. 2012). This dataset uniquely offers individual level information on injuries.Footnote 7 Overall, the dataset includes between 600,000 and 1,400,000 individual records for each of the 18 years in the sample. It provides information on individual and job characteristics (age, sex, place of birth, type of occupation, type of contract, family allowances, tenure, firm age, sector, size of firm, number of leave-adjusted full-time equivalent weeks worked in a year, part-time job, earnings) of regularly employed workers in the private sector. It also includes information about the number of work-related injuries (all of which are certified by physicians), their level of severity, and the lost days of work. Hence, our data set provides an exceptionally rich source of information which we use to analyze the joint distribution of earnings and workplace injuries.

Despite this wealth of information, there are three main limitations in our data. First, a precise estimation of injury risk is only available for employees in the non-agricultural private sector, as employees in other sectors are either not covered (public sector, agriculture and fishing), or the available information is inadequate to measure the exposure to injury risk (hours of work and days of work for self-employed workers are imprecisely measured). Lack of reliable information also forces us to exclude domestic workers, which is particularly unfortunate considering the importance of this sector for female immigrants’ employment in Italy. Therefore, as mentioned, we focus on male workers.

Second, like many administrative records used to compute social security benefits, our data set has no information on education nor a very detailed occupational classification, as these variables do not enter the benefit formula directly. Fortunately, the data does include information on whether the worker is a blue or a white collar, or whether she has managerial tasks, which tends to be highly correlated with education.

A third set of considerations concerns the internal validity of our results. Indeed, the workers in our administrative dataset had access to a regular contract. Since the 1998 immigration reform popularly known as Turco-Napolitano, stay permits are yielded conditional on having access to a regular work contract. Hence, it is fair to consider that all workers in our sample were regularly residing in Italy in the considered period. Moreover, access to a regular contract implies for the wide majority of workers to be subject to collective bargaining agreements. This should reduce the relevance of “chilling effects” and underreporting (Watson 2014) for the foreign workers in our sample. Nonetheless, regularly employed immigrant workers may be particularly reluctant to report their injuries if they fear that this will lead to a termination of a fixed-term contract (Boone et al. 2011) and if they have not yet access to a long-term residence permit (“Carta di Soggiorno Permanente” until 2007), which is yielded after 5 years of regular residence (see Appendix section “The role of the 5-year requirement for long-term stay permits”). These considerations led us to study not only injuries as a whole, but also what, in this paper, we refer to as “severe injuries”. The definition of severe injuries is not simply based on whether the injury leads to a particularly complex medical condition of the victim, but also on whether it requires immediate hospitalization (Bena et al. 2012). In other words, we could also refer to these as “immediate-care” injuries. The specification is relevant because, due to the fact that they require immediate hospitalization, these injuries are not subject to reporting bias, unless in extreme cases of criminal behaviour (Leombruni et al. 2019). Hence, in relation to the population of workers employed with regular contracts, measurement error and reporting bias should have negligible effects at least for what concerns severe injuries, that lead to very similar results as overall injuries.Footnote 8

However, lacking data about less protected informal employment probably lead us to underestimate actual workplace injuries. More specifically, Bianchi et al. (2012) have shown, using data from regularizations (1995, 1998, 2002), that there is a high correlation between the number of documented and undocumented migrants. Bratti and Conti (2018) have provided further evidence that the spatial distribution of irregular migrants is highly correlated with the one of regular migrants, over province and over time. This indicates that the ratio between regular and irregular migrants have remained constant in the period under observation. According to Bianchi et al. (2012), the ratio of irregular to regular migrants was about one-third. Relying exclusively on documented migrants implies that, according to them, we are omitting from the analysis a proportion of foreign born workers in Italy that is fairly constant and close to one-third. The working conditions of irregular immigrant are presumably worse than those of the regular ones; even if, in principle, the INAIL insurance coverage and the access to the national health system are guaranteed in Italy to both documented and undocumented migrants, the latter are probably more inclined to underreport their injuries, and more reluctant to access the INAIL or the public health services in case of injury. Hence, the results shown in the paper have to be considered as a lower bound of the issue at stake.

Our dataset allows investigating a time span of 18 years, during which a number of significant macroeconomic and policy changes of relevance to immigration occurred: considering that restrictions to regular employment are considered among the legal and institutional risk factors for severe labor exploitation (FRA 2015), these changes are likely to have an effect on the distribution of wages and injuries among foreign workers.

In what follows, we will split our data into four periods of approximately equal length, aiming to ensure relatively uniform institutional framework and economic cycle conditions. The first period covers 1994–1998, a period marked by increasing unemployment rates across the country and by the entry into force of the Schengen Treaty establishing free movement of people within the EU. During the second period, 1999–2002, still corresponding to a mainly negative phase of the economic cycle, the first of the two major immigration reforms in Italy, Law nro. 40/1998, popularly known as Turco-Napolitano after its proponents, was passed. The law introduced the first restrictions to immigration flows, conditioning residence permits for immigrants to having a job. The third period, 2003–2007, witnessed a more positive phase in the cycle, the EU enlargement from 15 to 27 Member States and the entry into force of the second immigration reform, Law nro. 189/2002, popularly known as the Bossi–Fini law, which introduced some further restrictions to residence permits for immigrants. The fourth period, lasting from 2008 to 2012, encompasses the years of the Great Recession.

3.2 Descriptives

Descriptive statistics for 1994, 2003 and 2012 are reported in “Appendix” in Table 1. While substantial gaps and differences emerge between the groups of natives and foreigners, a tendency towards convergence can be noted for most variables.

In Table 2, we report the factors that correlate most strongly with injury risks. The results unambiguously indicate that workers having spent a longer time within the same work relationship and are employed with open-ended contracts are significantly less likely to get injured. The age coefficient is negative for overall injuries but positive for severe injuries. This suggests that age, presumably due to experience and knowledge of the tasks, allows workers to prevent the occurrence of less severe injuries, but that ageing may be detrimental for job safety if it entails a deterioration in the physical abilities that workers need to perform safely at work. Interestingly, labour market experience affects the probability to get injured differently for foreign and native workers, indicating learning effects for natives but not for foreign-born workers. We interpret this as an indication that foreign workers are exposed to cumulative and self-reinforcing dynamics that prevent their investments in skills and safety upgrading and lock them into more and more dangerous jobs and tasks (see discussion in Appendix section “Factors affecting injury rates”).

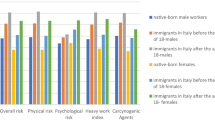

Other aspects of the working conditions of natives and foreign workers that may affect their vulnerability but that we cannot directly control for in our analysis are reported in Table 4. The information is drawn from the 2009 release of the Italian Labour Force Survey and is compared with the insights on the distribution of injuries that can be drawn from our administrative data.

For the sake of comparison, we also report in Column 1 the descriptive statistics on absence from work (illness, injury o temporary disability) for aggregated ethnic groups. Italian workers turn out to be more absent from work than workers from New Member States (i.e. Romania, Bulgaria). Workers from North Africa display more absences than Italian workers.

Workers from North Africa are also relatively more likely to be involved in shift work than Italian workers or workers from NMS3 (New Member States accessed in 2007, mainly Romanian workers). The second and third columns of Table 4 report the percentages of workers involved in evening and night work, respectively, by nationality groups. Workers from North Africa, as well as from other high migration pressure areas, are more likely to engage in evening and night work than Italians and workers from NMS3.

This may lead to an increase in the risk to get injured during evening and nights. To gain insights on this, we can leverage the availability, among our administrative data, of information on the time of the injury. Clearly, this is only available for the minority of workers who experience injuries. Hence, it is useful to draw some descriptive facts regarding the more vulnerable labour market status of immigrants but cannot be employed as a proxy for night work nor included among the propensity scores covariates.

Indeed, while most injuries occur during day time—because most workers work during the day shift, our administrative data indicate some concentration of reported accidents at 0 am (6.46% of all injuries, which is higher than the 4.16% that would prevail if injuries were uniformly distributed over the 24 h, and even higher considering that only a minority of workers are working during night shifts). The unconditional distribution of severe injuries is similar, but these injuries are relatively more likely to occur between 5 and 7 am. Considering as “night” any working hours after 7 pm and before 8 am, foreign-born workers are indeed 4% more likely to get injured during night hours.

We would expect the inclusion of proxies for night work work to decrease the gap in injury rates. In general terms, the groups of foreign workers who, based on LFS data, are more likely to work at night, are found to experience higher injury rates in our data. On the contrary, workers from New EU Member States in Eastern Europe are less likely to work during night shifts according to LFS data and, indeed, experience lower injury rates. Nonetheless, the extent to which our estimates may be affected by the inclusion of a measure for night work is difficult to predict. The extent to which night work can be a risk factor depends to a large extent on unobserved factors such as firm’s internal safety regulations—the manufacturing firms requiring their workers to engage in night work may want to implement specific measures to ensure the safety of their workers during night shifts. The vast majority of workers get injured during the day, and the magnitude of the gap in injury rates that we estimate is about ten times larger than the difference in the probability to get injured at night. This leads us to expect that the inclusion of this term would decrease, but not entirely explain the injury gap; nonetheless, this point should be addressed by further research devoted specifically to the issue.

Information on Saturday and Sunday work from the LFS, shown in Columns (4) and (5) of Table 4, indicates that NMS3 workers (i.e., mainly Romanian workers) are more likely to work on Saturday than Italian or North African workers. In turn, Italian workers engage more in Sunday work than other ethnic groups with the exception of workers from Near and Middle East. The distributions of foreign-born and native workers’ injuries over weekdays drawn from administrative data, however, display similar distributions, not highlighting a specific tendency of foreign-born workers to get injured during weekends. Rather, immigrants appear slightly more likely than natives to get injured on Friday and slightly less likely to get injured on Monday.

As regards natives’ and foreign workers’ propensity to work overtime, LFS data on the number of hours usually worked, the number of hours actually worked during the last week, and the amount of paid and unpaid overtime is reported in Columns (6)–(9). There are no striking differences between Italian workers and the largest ethnic groups in Italy. However, sector and task heterogeneity may still be present, since the length of the working time may depend on the harshness of the task undertaken.

The above is confirmed by the analysis of the injury data, with an important specification. Indeed, our data also report information relating to the so-called “ordinal hour” of the injury, i.e. the time since the start of the shift. For both native and foreign workers, about 50% of the injuries occur within the first 4 h of the shifts. Foreign workers’ injuries are only slightly more likely to occur after the 8th hour, i.e. 0.06% more frequently, hence from this point of view the concentration of foreign workers’ injuries during “long” hours is only quite limited.

However, foreign workers’ injuries appear significantly more concentrated within the “zero” hour (i.e., right after starting the shift). Even when excluding injuries having occurred on the way to and from work, foreign workers are 6% more likely to get injured during this “zero hour”. Clearly, this is no clear evidence of concentration of foreign workers during long hours. Yet, it is possible that this excess in injuries is due to undeclared overtime work having occurred on the day before the injury is declared, and may indicate the presence of “gray” work among these workers. Another possible explanation is that this excess of injuries during the hour “zero” of work is due to the accumulation of stress and of efforts, either in regular or irregular work, that make the worker tired even before starting to work. A full estimation of the share of regularly employed workers who engage in forms of “gray” work is beyond the scope of this paper, yet these statistics provide further indication that foreign workers may be viewed as more vulnerable workers even when they are regularly employed.

4 Results

4.1 Wages

The time trends of the foreign-native earning gaps are illustrated in Fig. 2, which reports the overall gap (the solid line) along with its explained (dashed) and residual unexplained component (dotted). The average foreign-native gap in weekly wages is slightly below 30%; it has increased between 1999 and 2009 and stabilized since then, like the explained component.

The “residual” component of the gap, i.e. the one that is attributable to the migrant worker status, has grown until 2003 and stabilised around 10% since then. These results are somewhat smaller but in line with the recent findings in the literature on the wage gaps of immigrants. Interestingly, no substantial reduction in the wage gap seems to occur during recession; this means that job destructions do not alter the left tails, and their differentials, in the wage distributions of the two populations.Footnote 9

4.2 Injury risk

To study the distribution of injury risk (Fig. 3), we constructed cells of homogeneous characteristics (gender, age class, qualification, family allowances, region of work, semesters of tenure, type of contract, sector, firm size and firm age) separately for natives and foreigners and computed the average injury risks per cell. Based on the range observed over the 18-year period, we assigned the injury rates of each cell to 80 risk classes of equal size. Counting the individuals in each cell and each risk class, we computed the relative shares of immigrants and natives in each risk class over their respective subsamples. Reweighting the count of individuals in each cell by the DFL weight and computing the share of each class over the counterfactual sample we obtained the counterfactual distribution. Because injuries are rare events, the wide majority of our sample concentrates in the zero risk class; to ensure statistical power in the higher classes, we pooled the data over the 18 years and dropped all classes above 10 (i.e. above 3 injuries per person-year; yet, the yearly distributions closely resemble the pooled one).

The left panel of Fig. 3 reports the entire distribution for all injuries; the right panel zooms on the non-zero risk classes.

Immigrants’ distribution is clearly right-shifted compared to the natives’. If natives had the same characteristics as foreigners, their counterfactual distribution would also be more right-skewed and we would observe a higher average injury risk. Interestingly, though, this explains the greater concentration of immigrants in moderate risk classes, but not in high risk classes, which must be attributed to the immigrants’ status.

Moving from the distribution to the analysis of average injury rates over time, the left panel of Fig. 4 reports the trends in average injury rates for foreigners, natives, and counterfactuals.Footnote 10 Injury rates of foreign workers exceed the natives’ in all years. The increase in the injury rates is sharpest for foreigners, during the 1998–2001 period. Later, injury rates show a gradual reduction that accelerates during the years of the economic crisis, especially for foreigners, in accordance with the pro-cyclical nature of injuries (e.g. Asfaw et al. 2011; Boone et al. 2011; Boone and van Ours 2006). Overall, the graph confirms the higher volatility of immigrants’ injury rates along the cycle.

An alternative explanation may be that the reduction is driven by underreporting. As noted by Boone and van Ours (2006), workers, especially during recessions, may underreport their injuries. In principle, if foreign workers are exposed to stronger pressure than natives, we may observe more underreporting among them (i.e. a larger differential between the overall injury rate and the rate of severe injuries).

Based on our considerations regarding internal validity, we are confident that the gaps in severe injury rates that we display in Figs. 9 and 10 in the Appendix can be taken as accurate approximations of the real gaps. The distributions of severe workplace injuries over time, by classes of risk, and by wage deciles are very similar to those of overall injuries. This similarity in patterns holds throughout our analyses and leads us to conclude that the presence of underreporting is not supported by the data.

Trends in injury rates and relative risk, 1994–2012. Average yearly injury rates (left) and associated relative risks (right). Relative risks calculated as ratios of injury rates in the relevant subsamples in each year. Overall gap: foreigners to natives; explained: counterfactual to natives; residual: foreigners to counterfactual

As is standard in the epidemiological literature, we also compute relative risks and report them in Fig. 4. This remains higher than 1.75 and close to 2 until 2009. The smoothly declining trend in the injury gap (the dashed-dotted line) seems mainly due to the gradual reduction in the unexplained component (the dotted line). The explained component of the gap (dashed) has remained fairly stable until 2008. The decline in the explained component during the recession may be due to a convergence in observable characteristics among natives and foreigners during this time, e.g. if natives go back into jobs they previously left to foreigners (see also Appendix section “Concentration curves”) or if immigrant-specific jobs disappear. Also, it could be attributed to the change in the composition of the immigrant population; indeed, over the 2000s, the share of foreign workers from Eastern European countries, who have very low injury rates, increased sharply (cfr. Bena and Giraudo 2014).

Overall, about 45–50% of the gap in severe injury rates can be attributed to fairly stable immigrant-specific factors (a figure which is comparable to the findings in Bena and Giraudo 2014, for stratified samples).

Comparing the trends in the wage gaps with those in injury rates between 1997 and 1999 provides a first indication that our proposed mechanism may be at work.

Between 1997 and 1999 the Italian economy was hit by the domestic effects of the South-Eastern Asia crisis. The decline in the wage gap observed over this period is consistent with the results in Biddle and Hamermesh (2013) for the US, who report that, besides facing greater employment volatility, African–Americans experience less wage discrimination during downturns. These effects, they argue, are attributable to compositional effects, and to the fact that some workers change their jobs with the recession.

In our setting, too, compositional effects appear important, as the decline in the wage gap is almost entirely explained by workers’ observable characteristics. However, due to the greater rigidity in the Italian labour markets (Devicienti et al. 2019), we are tempted to attribute the decline in wage gaps to job destruction rather than to job mobility (see also the discussion in Appendix sections “Hazard of exiting employment” and “Firm closure”).

In our application, adding workplace injuries to the analysis enriches the set of insights that can be drawn. Moreover, in our application, the availability of workplace injury data enables us to enrich the analysis of how wage gaps change during in recessions with the important additional component of workplace safety. Indeed, while wage gaps decrease, injury rates increase for both immigrants and natives over the considered period. This indicates a general worsening of working conditions for all workers—in terms of both wages and workplace safety. Injury rates increase comparatively more for immigrants, leading to an increase in the relative risk. This implies, in our model, that the observed combinations of wages and workplace safety move closer and closer to the corner solution, at which wages are at their minimum and risk is high. For marginal workers faced with the most disadvantageous combinations, most of which are immigrants, this implies job destruction.

Coherently, the unexplained component of the relative risk increases over the same period and drives the overall results. The composition of immigrants in terms of countries of origin seems to play a little role in this context, considering that the main change observed over the considered period is the decline in the share of Western Europeans, who are not counted among the “high migration pressure” countries.

4.3 Conditional distributions of risk by wage

To gain further insights on workplace safety differentials, we turn to the joint analysis of the wage and injury gap. Exploiting the main advantage of the DFL approach, we construct a distributional counterfactual and study the functional form of the joint distribution of wages and injuries for our three considered subsamples (similarly to Barsky et al. 2002).Footnote 11 Figure 5 explores the relationship between injuries and wages by splitting our subsamples into deciles of weekly wages. This approach seems particularly appropriate considering the well known issue of the social gradient in health, as well as our previous discussion on the empirical negative relationship between wages and injury risk (e.g. Hamermesh 1999a).Footnote 12

To derive the counterfactual distributions, we obtain the quantiles of the counterfactual (i.e. DFL-reweighted) distribution of wages, then compute the decile-specific injury rates, as regards both overall injuries and severe injuries.

In relation to the joint distribution of injuries and wages, the comparability between the native and foreign-born groups is particularly important to ensure the validity of the results of the DFL decomposition. Hence, in order to maintain the weights within a reasonable range and to mitigate unobserved heterogeneity, we focus in this analysis on male blue collar workers in the manufacturing sector.

In all figures, the foreigners’ schedule lies above and to the left of the schedule for natives, and in most cases also above the counterfactual. Hence, not only is their wage distribution shifted to the left, but, by similar levels of wage, they display higher injury rates, in line with the interpretation of a segmented labor market (Orrenius and Zavodny 2013) and with the hedonic wage model presented above. Observable characteristics explain a large part of the gap, but the unexplained component is significant at specific wage levels. Another stylized fact emerging from our analysis is that the reduction in the overall gap in injury rates observed above translates into a gradual reduction of the slopes of the curves over time, leading to a very flat distribution in the recession sub-period of 2008–2012. The decline in injury rates over time applies to all subsamples but is more marked for foreign-born workers. As shown in “Appendix”, the results are robust to a wide set of robustness checks. In particular, the results hold when restricting the analysis to severe injuries only—which indicates that the results are not driven by under-reporting of less severe injuries, notwithstanding the lower statistical power due to the rarer phenomenon at stake (Fig. 11). They are also confirmed and even more marked when we restrict the analysis to the subsample of workers having worked the whole year and if we study the metal-mechanic sector only, hence a set of workers who are subject to a single collective contract (Figs. 13, 14). Results are also robust to excluding workers hired during the last month of the year.

Finally, the set of regressors that we include in the probit models that we employ to compute our weights may affect our results. In the light of the peculiar role of labour market experience plays for injury rates, in Fig. 15, we report the results of an additional analysis where the usual set of regressors is augmented with the difference between a worker’s age and his age at the first recorded employment in Italy.Footnote 13 The robustness of these results is reassuring that the large set of regressors that we include captures most of the variation in the phenomenon at stake.

Injury rates by weekly wage decile. Male blue collar workers in the manufacturing sector. Deciles of the counterfactual distribution obtained by reweighting the distribution of wages prior to calculating the deciles. Injury rates and 95% Poisson confidence intervals computed for each decile and each subsample. Union wage floor ranges relevant for the sub period (constant prices, base year 2012) for all manufacturing sectors reported as dashed gray lines, as solid lines for the metal-mechanic subsector

Qualitatively similar results are obtained when studying the distribution of annual wages rather than weekly wages (Fig. 6); in this case, the results are driven by the fact that immigrants are disproportionally employed with shorter contracts. Unsurprisingly, this category displays the highest injury rates (among natives as well as foreigners), considering that the literature, as well as our own results in Table 2, have identified on-the-job tenure among the most significant protective factors against workplace injuries. The higher risk among foreigners is consistent with the observed concentration of foreigners in less protected jobs with more precarious contracts, and is to a large extent attributable to observable characteristics; its marked decline in 2008–2012 could be attributed to the job destruction operated by the global financial downturn which affected non-tenured contracts more heavily.

Injury rates by annual wage decile; all injuries. Male blue collar workers in the manufacturing sector. Deciles of the counterfactual distribution obtained by reweighting the distribution of wages prior to calculating the deciles. Injury rates and 95% Poisson confidence intervals computed for each decile and each subsample. Union wage floor ranges relevant for the sub period (constant prices, base year 2012) for all manufacturing sectors reported as dashed gray lines, as solid lines for metal-mechanic subsector

More generally, all figures clearly show the empirically negative relationship between wages and injury risk that is discussed in the literature and that confirms that lower-wage workers are at higher injury risk. Yet, the injury rates of foreigners are significantly higher than the natives’ and the counterfactual’s even by higher wages.

We observe a marked change in the slope of the curves at wage levels corresponding to ca. 18,000 Euros yearly, an amount compatible with the minimum level of earnings set by collective bargaining for most manufacturing sub-sectors, whose range is indicated by the gray bars in the figures. Within the range of the union wage floors, we observe the largest and most significant differences in injury rates between foreigners and counterfactual.Footnote 14 Above these levels, as wages grow, injury rates decline monotonically.

The wage levels for the lowest deciles appear to decline over time in real terms, and more markedly so for foreign workers. This may be attributed to the labor market reform introduced in 2003, that increased the share of workers employed with non-standard contracts, hence not subject to the collective bargaining provisions. Nonetheless, the excess of risk in correspondence to the contractual wage floor still applies even if we restrict the analysis to workers with standard open-ended contracts.

Overall, the injury gaps between foreigners and natives seems mainly driven by two facts: the higher injury rates observed in the lowest wage quantiles, which exceed significantly the level predicted by observed characteristics at union wage floor levels; and the persistently higher injury rates observed for higher quantiles. The gaps are largest and most significant in the 1998–2002 and 2003–2007 sub periods. The estimates are less precise but qualitatively similar in the 1994–1998 sub-period, where immigration in Italy was still a new phenomenon, hence we have less observations for migrants.

5 Discussion

The analysis confirmed that the combined injury and wage gap faced by foreigners is not entirely due to differences in the observable characteristics, and that a non-negligible component in the wage and risk gap remains attributable to the unobserved characteristics of immigrants.

According to our results, the unexplained foreign workers earning gap amounted in the more recent years to ca. 10% of average wages. Even controlling for observable characteristics, foreign workers’ injury risk exceeds that of natives by between 16 and 37%. The picture is even more serious when looking at severe injuries, as the corresponding excess risk is between 24 and 47%. As mentioned, as we are only considering workers employed with regular contracts and serious injuries are not subject to reporting bias, we may take the latter as a credible estimate of the actual gap in workplace safety.

The analysis of the injury rate conditional on wage showed that the greatest and most significant component of the gap is localised at the union wage floor level set by collective bargaining. The excess of injuries of foreign workers in proximity of the threshold could be explained within the framework of the hedonic wage model introduced in Sect. 2. As we discussed, for different reasons, the “unrestricted” wage that employers would offer in absence of minima would possibly be located below the threshold. Collective bargaining, however, imposes them to pay the minimum. Hence, employers need to move to a higher bundle of wage and injury risk; their increased expenditure for wages needs to be counterbalanced by a lower expenditure for safety. This unintended risk-increasing effect of the wage floor is compatible with previous findings by Leombruni et al. (2013) who showed that, due to the downward rigidity of wages, human capital losses due to displacement translate into greater risk and not into wage losses. According to this interpretation, lower-skilled immigrants would result as marginal workers, employed at a corner solution.

Hence, employer-driven segmentation in a wage-rigid labor market may be among the determinants of the higher risk born by foreign workers, adding up to possibly heterogeneous risk preferences between natives and immigrants. If the underlying labor supply curve is differentiated between natives and foreigners (cfr. Viscusi and Hersch 2001), employing foreigners may be a way to save on labor costs, including on safety costs. In turn, selection effects determined by workers’ and firms’ heterogeneity may cause foreign workers to be more subject to fluctuations in the macroeconomic conditions than other workers.

When the economy is in a bad state, the bundles of wages and injury risk that the firm can offer shift to lower wages and higher risk. The downward rigidity of wages constrains the wage cuts and may induce firms to save on safety, rather than wages, to the extent that the implied level of risk may become legally unaffordable. Hence, recessions may cause workers to disappear from the formal labor market. Their disappearance reduces exposure in addition to the reduction in the work pace that, per se, reduces injuries and would explain the observed decline in injury rates.

Furthermore, within the same job/firm, the isoprofit curve associated with more productive workers would decrease less than the isoprofit curve associated with less productive workers. Hence, the flattening of the curves in Figs. 5 and 6 may be due to a selection effect which destroys the jobs located at the corner solutions. Only the jobs for the (unobservably) more productive workers would remain, making the negative relation between salary and risk less evident than it was in previous years.

This interpretation is supported in a set of duration analyses performed on the hazard of exiting employment reported in Appendix section “Hazard of exiting employment”. Foreign workers are found to face significantly higher hazard than natives. The hazard of loosing jobs increases with regional unemployment rates, while wage levels are found to have a significant protective effect.

A second selection mechanism that may lead to the observed reduction in migrants’ injury rates could depend on the distribution of firms’ unobserved attributes (i.e. not controlled for in our reweighting procedure) and may thus be determined by changes in the composition of employers over the business cycle. In a set of tobit regressions on synthethic firms (see Appendix section “Firm closure”), we show that firms characterized by lower average wages, higher injury risk and a higher percentage of foreign workers are more likely to close during the time of the Great Recession.

Both selection mechanisms make foreign workers more likely to experience job losses and thus contribute to explain the overall observed reduction in migrants’ injury rates. Such a decrease, however, concerns only jobs observed in the formal sector. As shown by Leombruni et al. (2019), workers are more likely to exit the formal labor market and to undertake jobs in the informal sector during recessions, with even more serious implications for their workplace safety.

Another possible explanation for the observed patterns relates to job intensity. If foreigners are assigned to more effort-intensive tasks (not captured by our variables), during recession the overall decline in job intensity would decrease foreigners’ injuries comparatively more than natives’, particularly in the lower deciles. The alternative argument that during recessions severe injury rates remain unchanged but underreporting increases (Boone and van Ours 2006) is not supported in the joint analysis of injury rates by wage: aggregate and severe injuries display very similar patterns. In a set of unreported analyses, we plotted the ratio of severe to aggregate injuries by wage decile in the four sub-periods, without detecting any significant increase among the lower-waged foreign workers.

A limitation of this work is that within the present design we cannot tell the effects of potentially opposing factors, such as the change in the composition of the immigrant population, from the effects of the crisis which may actually increase the incentives to underreport, as suggested by Boone and van Ours (2006). In particular, from 2006 on, the foreign-born population of Romanian origin, known to have peculiarly low injury rates (Bena and Giraudo 2014), has been gaining the leading share of the foreign population.

To gain insights on possible compositional effects, in Appendix section “Compositional effects” we run separate analyses for the two most represented national origins of foreign workers, i.e., Morocco and Romania, and apply our methodology to a subsample that excludes Romanian workers. The results for the single nationalities (Figs. 21, 22) reveal opposing patterns. In 2008–2012, Moroccan workers display a downward shift in injury rates that is comparable to that of foreign-born workers as a whole. Romanian workers, instead, who are characterised by lower-than-average injury rates (hence are possibly less marginal than Moroccans), do not change their position significantly. Reassuringly, however, the results for the sample that excludes Romanian workers are remarkably similar to our main results. Hence, the decrease in foreigners’ injury rates may be attributed to the combined effect of the job destruction faced by marginal workers/firms and the increased weight of the Romanian workers, where, however, the role of compositional effects seems to be limited and the job destruction effects of macroeconomic changes seem to prevail. Indeed, their relatively skilled profile ensures that Romanian workers are not heavily represented among the lowest-wage/highest-risk deciles.

As regards foreign workers with greater wage potential, we still observe injury rates that significantly exceed the level predicted by observable characteristics. Even in the higher-wage part of the distribution, injury rates decline as salary increases, but this decline less marked for foreigners. Moreover, their observable characteristics would predict a sharper decline than is actually observed. Overall, the immigrant status seems to affect injury rates even by workers with greater wage potential.

Overall, the immigrant status seems associated with a reduced ability to buy safety in exchange of wages. Additional evidence presented in “Appendix” suggests that, among foreigners, the within-group distribution of injuries by wage is fairly equal and almost close to perfect equality in the 2007–2012 sub-period (Fig. 25). Conversely, natives display concentration of injuries by lower wages. Hence, as salary increases, natives are able, to greater extent than immigrants, to raise workplace safety as well.

6 Conclusions

Comparing counterfactual scenarios for natives with the actual distributions of immigrants reveals a strong labor market segmentation where differentials in wages and injury risks cannot be attributed to observable characteristics.

Our focus on the joint distribution of injuries and wages highlights novel aspects of the unequal distribution of injuries by wage. On the one hand, lower-skilled migrants are marginal workers enduring worse working conditions at any level of wages; on the other hand, they face greater risk of losing their jobs during recession. This leads the overall gap in injury rates in the formal sector to decrease over time. As a matter of fact, our results show that workplace safety, wages and employment are closely interconnected and that their dynamics should be analyzed jointly.

The analysis of the shape of these joint distributions around minimum contractual wages and the regressions on firm closures suggest that the injury gap and its dynamics may also be affected by unobserved heterogeneous attributes of employers. Unfortunately, as commonly acknowledged by analyses on hedonic models (Rosen 1974), the presence of unobserved heterogeneity in workers and employers’ attributes does not allow us to disentangle the effects due to firms’ productivity from those entailed by tasted-based or monopsonistic discrimination (Manning 2003). Whatever the source of this heterogeneity, our findings are suggestive that the greater risk borne by immigrants is related to their overrepresentation in “worse” (i.e. riskier, less productive) firms.

Equality concerns, therefore, strongly point to the need to shed light and to intervene on the sources of such a concentration of workplace risk. Currently, the agency in charge for workplace safety monitoring in Italy (SPRESAL) intervenes either randomly or upon request by concerned employees. According to our results, firms displaying a peculiar concentration of low wages may be considered to be at high risk and stricter monitoring may be foreseen for their case. Stricter enforcement of the safety monitoring implies, in Italy, that concerned firms will, as a minimum, have to prepare a “Risk Assessment” document that enumerates the potential sources of risk along with the interventions to mitigate it. Such a document is currently not implemented by all firms. This may be important in understanding whether the hazard comes from individual conduct (e.g., the need to improve the use of individual protection equipment) or from the organization of the production process (e.g., if the pace of work is too fast to ensure compliance with the safety standards).

On the other hand, as mentioned, workers trade-off safety for wages. This suggests that the overall welfare effects of a strong enforcement of a minimum level of safety conditions, combined with minimum contractual wages, are a priori ambiguous. As emphasized by the literature on monopsony (Bhaskar and To 1999; Manning 2003), these restrictions may lead to firms exit, and this may represent, especially for immigrants, a strong reduction in work opportunities. In addition, the destruction of formal jobs recorded by administrative datasets may be followed by an increased participation of foreign workers in the informal sector, where the workplace safety conditions are plausibly even worse. It is possible that, especially during downturns, more liquidity-constrained workers would increase their tolerance to workplace risk and to irregular contracts. Downturns may also affect firms’ ability to offer contracts that comply with the legal standards in safety and wages, and more generally to invest in safety. We envisage in this regard an important role for public intervention either in the form of income support measures or in direct support for regular firms, along with ever-needed measures to fight informal labour markets.

Our study also indicates the need that future studies address the safety impact of policies aiming to reduce informality, so as to get a more reliable appreciation of the extent to which our results underestimated workplace injuries in informal labour markets.

As regards the investigation of the sources of the concentration of workplace risk, we showed that labour market experience has opposite effects on workplace safety for natives and foreigners, with immigrants’ safety conditions worsening over time. As discussed, this may be the result of cumulative and self-reinforcing effects of the initial allocation of immigrants to dangerous tasks, that increasingly segregates these workers into risky and lower-wage tasks. This may occur because, at the beginning, they master the language less well and are not equally able to implement correct safety behaviours. Similarly to what has been observed for wage gaps, this initial downgrading may reduce the motivation for the worker to invest in language and skills upgrading (Hammarstedt 2006; Kee 1995; Lee and Wolpin 2006; Angioloni and Wu 2020). This is also in line with the results by Bena and Giraudo (2014), who find that tenure does not moderate the high injury risk faced by Moroccan workers in Italy.

These dynamics imply skill downgrading and mismatch for foreign workers that are to some extent avoidable. While mismatch is the result from the complex interaction of demand and supply dynamics, the language difficulties of newcomers can be addressed via early language trainings. Enrolment in a language training could become a requirement for the renewal of the ordinary stay permits and not only for the long-term permit, as it is currently the case. Proficiency in the Italian language can be expected to improve the ability of foreign workers to understand and comply with safety regulations, coherently with the findings by Orrenius and Zavodny (2013) who found that language proficiency is a key protective factor against injury risk. Language proficiency can be expected to improve the quality of the matching process between workers and firms, which is a socially desirable result for a country competing for skilled labour with other countries. Parallel to this, it seems crucial that all firms implement adequate safety trainings, and that such implementation is carefully monitored.

More generally, even if we showed different behaviours for natives and foreigners, the first year of employment appears critical for both groups of workers—for immigrants, because it triggers self-reinforcing effects later on; for natives, because it represents the year with greatest risk of injury. Hence, elements of safety training may become part of the curricula of professional and technical schools. Considering that many students with foreign origins attend these schools, this would serve the double purpose of promoting safety training among early entrants in the labour market, and of promoting its knowledge among future workers with a migration background.

A side-result of our analysis is, finally, to highlight the need to accelerate the process of harmonisation of data collection on workplace injuries, an effort that is in place in the EU within the ESAW project (European Statistics on Accidents at Work), and possibly to extend it beyond the EU. While, at least in the EU, there seems to be consensus regarding the need to collect comparable and reliable data on workplace injuries, the available information regarding immigrant workers remains scant, which adds to even more serious lacks of data on workplace injuries in the countries of origin. Even recognising the difficulties in comparing data stemming from different insurance systems, collected with different criteria and diffused with different methods (Mekkodathil et al. 2016), such an effort would have substantial implications. It would help to disentangle whether the gaps in injury rates between natives and foreigners can be explained by home country specificities (e.g., general levels of education, a specific industrial culture that makes some groups more sensitive to safety issues) or by differential and potentially discriminatory treatment of specific groups in the country of destination.

Data availability

The data used are proprietary. Information on individual injuries is covered by a strict confidentiality agreement with the Italian Ministry of Health. For this reason, they cannot be made available nor deposited in a public repository. The data can however be accessed by any researcher establishing an agree- ment with the Italian Ministry of Health. The authors are ready to provide information to guide other researchers through the procedures for accessing the data on injuries. All results and descriptive statistics related to wages dynamics of Italian workers can be easily replicated with available WHIP data or other public datasets based on INPS archives (e.g. LOSAI).

Code availability

The empirical analysis were conducted in Stata. The scripts producing the empirical results are available upon acceptance of the manuscript.

Notes

We assumed immigrants and natives have the same indifference curves, but immigrants’ indifference curves may be flatter: especially in the early phases of the migration project, immigrants may accept risky jobs if these allow them to make fast money (cfr. Dávila et al. 2011).

As discussed in Barsky et al. (2002), one might be tempted to study the opposite, i.e. the counterfactual distribution of wages and injuries which would prevail if immigrants had the same characteristics as natives. This, however, would imply an extrapolation rather than an interpolation, and would increase the estimation error because a large set of combinations of characteristics that we observe for natives are not observed among immigrants. This makes natives a natural control group for immigrants, and not the opposite.

If these combinations could be fully explained by discrete data, the nonparametric analogue of this procedure would be to study the relative shares of immigrants and natives within the each of the cells corresponding to each combination of characteristics.

We would like to thank an anonymous referee for pointing out this issue.

The choice of such factual and unfactual groups is motivated by the need to ensure the largest possible homogeneity among each group of workers. The results are very similar when we use the whole of the foreign population (including immigrants from advanced economies) as the factual and the strictly Italian-born population as the comparison group, given that the population of foreign workers in Italy is largely composed of workers from HMP countries.

In all cases, we performed the analysis using two measures of injuries: (1) all reported and certified injuries; and (2) severe injuries, i.e. the more severe injuries requiring immediate hospitalization. The results are fully consistent but less precise for severe injuries, due to their smaller numerosity. Hence, for the sake of brevity in what follows we report the results for the entire set of injuries only. The main results for severe injuries are reported in “Appendix”.

Unfortunately, our data are not informative as to workers’ mental health, hence we cannot connect the occurrence of injuries with the sources of psychological distress on the job, which we recognise as a potentially fruitful avenue for future research. The only source of data on psychological distress in our administrative sample is the cases of sickness leave that are due to hospitalizations associated with a mental health diagnosis, e.g. for depression. This clearly represents an extreme case, and would only provide insights on a very small and specific subset of all possible mental health problems and psychological distress affecting workers. Moreover, these are data on sickness leaves and not on injury leaves, hence they cannot be directly linked to the occurrence of injuries.