Abstract

We study the behaviour of individuals with different geographic origins interacting in a same public good game. We exploit the peculiar composition of the experimental sample to compare the performance of groups where individuals have mixed origins to homogeneous groups. We find that, despite the absence of any geographic framing, mixed groups exhibit significantly lower contributions. We also find that cooperation levels differ significantly across geographic origins, in line with the existing literature. This is explained by a different impact of coordination opportunities, such as communication, as we show by manipulating them. Our results point towards integration as a crucial aspect for the economic development of intercultural societies. They also confirm that, rather than being explained just by the differences in institutions and economic opportunities, the Italian North–South divide embeds elements of distrust, prejudice and a consequent path dependence in the level of social capital

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Balliet et al. (2014) for a cross-country meta-analysis of in-group effects in cooperative games.

Vice-versa, in the experiment by Cappelletti et al. (2015), participants came from the same geographic area and were differentiated based on their knowledge of a specific local language.

In total, around 240 students were selected according to these criteria, and were distributed in different groups who participated to the larger project with a different timing. Hence, not all of them took part in the experiment being described.

More precisely, our subjects all had a mother not holding a university degree. The sample selection criterion, which encompassed both merit and social background, is explained by the scope of the larger project: the literature on intergenerational transmission of education points at the mother’s level of education as particularly relevant (Black et al. 2005; Pronzato 2012).

Bornhorst et al. (2010), Trifiletti and Capozza (2011) and Bigoni et al. (2018), for instance, look at samples of students originating from different cities/countries, but all enrolled in a same university. Vice-versa, in our case the geographic origin is proxied by the school attended—reflecting our desire to consider the environment where each participant was raised.

The six cities involved in the experiment were Cagliari, Napoli, Palermo (including one school in Partinico, part of its metropolitan area) for the South, and Massa, Milano, Prato for the Center-North. Participants from the Center are pooled with those from the North in light of the characteristics of their cities of origin, both located in Toscana. Bigoni et al. (2016), in their selection procedure, classify Toscana in the North based on its latitude. Such choice is reinforced by a look at socioeconomic variables they adopt as proxies for social capital: when compared to the average for Northern Italy, Toscana has higher association density (68.44 per 100,000 inhabitants vs. 36.57, South is at 25.52) and electoral participation (\(86.67\%\) vs. \(86.04\%\), South is at \(70.16\%\)), while it is close to the North for blood donations (42.52 every 1000 inhabitants vs. 47.88, South is at 25.51). Statistics for the South include the island regions of Sicily and Sardinia.

No reference of participants to geographic origin was recorded, neither during the experiment nor during the debriefing phase.

All groups were designed to have five or six members, but five groups out of sixteen had only four members due to absences. No group had more than three members from a same city (the algorithm used for creating the groups is described in detail in Appendix A).

The mapping between cards and participants was fixed since the beginning, allowing the experimenters both to record private earnings, and to return to each player the contributed cards after each round. For practicality, each participant was assigned four cards with the same number or face, two from a black suit and two from a red suit, e.g. “10 of clubs and diamonds”.

See Bochet et al. (2006) for a between-subjects analysis of face-to-face interaction in public good games.

This procedure incidentally allowed participants to verify that their contributions were recorded correctly: they were not allowed instead to reveal their cards to anybody else, hence preventing them from providing hard evidence concerning their contributions. Information during the first two rounds was actually more scarce than in most studies on anonymity in public games, in which participants know the composition of their group (Rege and Telle 2004) or total contributions of their group in previous rounds (Gächter and Fehr 1999).

While in our experiment the game was finite, subjects were ex ante unaware of its length—see Sect. 2.1.

Importantly, this comparison does not account for a taste for reciprocity. The tournament scheme can cause a decrease in contributions should subjects dislike favouring groupmates who contribute strictly less than them. However, results from our experiment suggest that this phenomenon is scarcely relevant, as contributions increase in those rounds in which subjects receive information about their groupmates’ (aggregate) contributions. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation.

In this and subsequent models, we insert a dummy variable for each phase, including the first: coherently, we do not insert in the model a constant term, which would be colinear with them. This choice clearly does not affect the results (we will look at comparisons between coefficients \(\alpha _P\) rather than at their individual values, and run significance tests in accordance), and it significantly simplifies the exposition.

In this test, we will exclude observations from phase I, when the groups composition is still unknown to participants.

In light of the possibility, for subjects, to influence each others’ decisions via communication, or information on past contributions, we also allow for non-independence by running the analysis at the group, rather than individual, level (where feasible), and obtain analogous results. See Appendix D.1.

We exclude from this test phase I, when participants did not know the composition of their group: we analyse this phase in Sect. 5.4 as a robustness test on the randomisation process.

Also see Sect. 5.3, where we look for, and do not find, a gender effect in contributions.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation.

Instead, removing round 6 from phase IV does not affect results for hypotheses (HcIV), (HmIV), and (HhIV). Results are available upon request.

While the incentives might have a different desirability for different groups of subjects, this does not alter the policy implications.

It is worth stressing that such tests pool together an intrinsic feature (the geographic origin) and a possible treatment effect (being in a North-only or South-only group).

We had already tested Hypothesis (Hn) on such a subsample, but pooling together all phases, that is, not looking for an effect of design changes.

References

Algan, Y., Hémet, C., & Laitin, D. D. (2016). The social effects of ethnic diversity at the local level: A natural experiment with exogenous residential allocation. Journal of Political Economy, 124(3), 696–733.

Andreoni, J. (1988). Why free ride? Strategies and learning in public goods experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 37(3), 291–304.

Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2004). Public goods experiments without confidentiality: A glimpse into fund-raising. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7), 1605–1623.

Balliet, D., Wu, J., & De Dreu, C. K. (2014). Ingroup favoritism in cooperation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1556–1581.

Banfield, E. C. (1967). The moral basis of a backward society. New York: Free Press.

Barrett, L. (2007). Oxford Handbook of evolutionary psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bigoni, M., Bortolotti, S., Casari, M., & Gambetta, D. (2018). At the root of the north–south cooperation gap in Italy: Preferences or beliefs? The Economic Journal, 129(619), 1139–1152.

Bigoni, M., Bortolotti, S., Casari, M., Gambetta, D., & Pancotto, F. (2016). Amoral familism, social capital, or trust? The behavioural foundations of the Italian North–South Divide. The Economic Journal, 126(594), 1318–1341.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2005). Why the apple doesn’t fall far: Understanding intergenerational transmission of human capital. The American Economic Review, 95(1), 437–449.

Bochet, O., Page, T., & Putterman, L. (2006). Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60(1), 11–26.

Bornhorst, F., Ichino, A., Kirchkamp, O., Schlag, K. H., & Winter, E. (2010). Similarities and differences when building trust: The role of cultures. Experimental Economics, 13(3), 260–283.

Brosig-Koch, J., Helbach, C., Ockenfels, A., & Weimann, J. (2011). Still different after all these years: Solidarity behavior in East and West Germany. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11), 1373–1376.

Buonanno, P., Montolio, D., & Vanin, P. (2009). Does social capital reduce crime? Journal of Law and Economics, 52(1), 145–170.

Camussi, S., Mancini, A. L., & Tommasino, P. (2018). Does trust influence social expenditures? Evidence from local governments. Kyklos, 71(1), 59–85.

Cappelletti, D., L. Mittone, & M. Ploner, et al. (2015). Language and intergroup discrimination. evidence from an experiment. CEEL Working Paper N. 1504, University of Trento, Department of Economics.

Cárdenas, J. C., & Mantilla, C. (2015). Between-group competition, intra-group cooperation and relative performance. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 33.

Cason, T. N., Saijo, T., & Yamato, T. (2002). Voluntary participation and spite in public good provision experiments: An international comparison. Experimental Economics, 5(2), 133–153.

Cassar, A., & Wydick, B. (2010). Does social capital matter? Evidence from a five-country group lending experiment. Oxford Economic Papers, 62(4), 715–739.

Chaudhuri, A. (2011). Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: A selective survey of the literature. Experimental Economics, 14(1), 47–83.

Cox, T. H., Lobel, S. A., & McLeod, P. L. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. The Academy of Management Journal, 34(4), 827–847.

Croson, R., & Buchan, N. (1999). Gender and culture: International experimental evidence from trust games. The American Economic Review, 89(2), 386–391.

Cubitt, R., Gächter, S., & Quercia, S. (2017). Conditional cooperation and betrayal aversion. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 141, 110–121.

Eckel, C. C., & Wilson, R. K. (2006). Internet cautions: Experimental games with internet partners. Experimental Economics, 9(1), 53–66.

Felice, E. (2013). Perché il Sud è rimasto indietro. Il Mulino.

Fershtman, C., & Gneezy, U. (2001). Discrimination in a segmented society: An experimental approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 351–377.

Finocchiaro Castro, M. (2008). Where are you from? Cultural differences in public good experiments. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(6), 2319–2329.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters, 71(3), 397–404.

Friedman, J. W. (1971). A non-cooperative equilibrium for supergames. The Review of Economic Studies, 38(1), 1–12.

Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (1999). Collective action as a social exchange. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 39(4), 341–369.

Gaudeul, A., & Giannetti, C. (2015). Privacy, trust and social network formation. Working Paper 269, University of Goettingen, Department of Economics.

Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., Rohorua, H., & Stillman, S. (2015). The Long-term impacts of international migration: Evidence from a lottery. World Bank Economic Review, 32(1), 127–147.

Goette, L., Huffman, D., & Meier, S. (2006). The impact of group membership on cooperation and norm enforcement: Evidence using random assignment to real social groups. American Economic Review, 96(2), 212–216.

Goette, L., Huffman, D., & Meier, S. (2012). The impact of social ties on group interactions: Evidence from minimal groups and randomly assigned real groups. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 4(1), 101–15.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). The role of social capital in financial development. The American Economic Review, 94(3), 526–556.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (1995). Economic growth and social capital in Italy. Eastern Economic Journal, 21(3), 295–307.

Hong, L., & Page, S. E. (2001). Problem solving by heterogeneous agents. Journal of Economic Theory, 97(1), 123–163.

Hoyman, M., McCall, J., Paarlberg, L., & Brennan, J. (2016). Considering the role of social capital for economic development outcomes in US Counties. Economic Development Quarterly, 30(4), 342–357.

Ichino, A., & Maggi, G. (2000). Work environment and individual background: Explaining regional shirking differentials in a large Italian firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 1057–1090.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

Lazear, E. P. (1999). Globalisation and the market for team-mates. The Economic Journal, 109(454), 15–40.

Leonardi, R. (1995). Regional development in Italy: Social capital and the Mezzogiorno. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 11(2), 165–179.

Levine, S. S., Apfelbaum, E. P., Bernard, M., Bartelt, V. L., Zajac, E. J., & Stark, D. (2014). Ethnic diversity deflates price bubbles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(52), 18524–18529.

Markussen, T., Reuben, E., & Tyran, J.-R. (2014). Competition, cooperation and collective choice. The Economic Journal, 124(574), F163–F195.

McLeod, P. L., & Lobel, S. A. (1992). The effects of ethnic diversity on idea generation in small groups. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1992(1), 227–231.

Nowell, C., & Tinkler, S. (1994). The influence of gender on the provision of a public good. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 25(1), 25–36.

Nuti, S., & Ghio, A. (2017). Obiettivo mobilità sociale. Il Mulino.

Ockenfels, A., & Weimann, J. (1999). Types and patterns: An experimental East–West-German comparison of cooperation and solidarity. Journal of Public Economics, 71(2), 275–287.

Oosterbeek, H., Sloof, R., & Van De Kuilen, G. (2004). Cultural differences in ultimatum game experiments: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Experimental Economics, 7(2), 171–188.

Pronzato, C. (2012). An examination of paternal and maternal intergenerational transmission of schooling. Journal of Population Economics, 25(2), 591–608.

Putnam, R. (2001). Social capital: Measurement and consequences. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 41–51.

Putnam, R . D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R . Y. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rege, M., & Telle, K. (2004). The impact of social approval and framing on cooperation in public good situations. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7), 1625–1644.

Rustagi, D., & Veronesi, M. et al. (2016). Social identity, attitudes towards cooperation, and social preferences: Evidence from Switzerland. Working Paper N. 01/2016, University of Verona, Department of Economics.

Savikhin Samek, A., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2014). Recognizing contributors: An experiment on public goods. Experimental Economics, 17(4), 673–690.

Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., & Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In M. J. Hatch & M. Schultz (Eds.), Organizational identity: A reader (pp. 56–65).

Trifiletti, E., & Capozza, D. (2011). Examining group-based trust with the investment game. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 39(3), 405–409.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank for comments Marco Casari, Alessandro Bucciol, Maria Bigoni, Valentina Rotondi, participants in the 2017 Royal Economic Society Conference, the CRIEP Workshop, the 14th University of Bologna Workshop on Social Economy for Young Economists, the 13th Maastricht Behavioral and Experimental Economics Symposium, the 58th Yearly Scientific Meeting SIE, together with participants in seminars at FBK-IRVAPP, University of Bolzano and University of Milan-Bicocca. We are grateful to Chiara Busnelli for her great support.

Appendices

Appendix A: Algorithm for the creation of groups

The following algorithm was implemented to subdivide participants of each session in four groups. Importantly, in each session, each school was represented by a maximum of three students.

-

1.

Create three empty lists: \({\mathcal {S}}\)(outh) with six slots, \({\mathcal {N}}\)(orth) with six slots, \({\mathcal {M}}\)(ixed) with 12 slots. A slot is occupied whenever a student is appended to a list.

-

2.

If the session has strictly less participants from the North (South), remove one slot to the \({\mathcal {N}}\) (\({\mathcal {S}}\)) list, respectively.

-

3.

Let I be the school with the most students among schools still not processed.

-

4.

Let \({\mathcal {L}}\) be the list \({\mathcal {S}}\) if the school is from the South, \({\mathcal {N}}\) otherwise.

-

5.

If \({\mathcal {L}}\) has a free slot, append a randomly selected student from I to it.

-

6.

If there are still students to be placed from I, append them to \({\mathcal {M}}\).

-

7.

If there are still schools to be processed, go back to point 3.

-

8.

Create two lists \({\mathcal {M}}1\) and \({\mathcal {M}}2\) from elements of \({\mathcal {M}}\) in odd and even positions, respectively.

The rationale for ordering schools by size was to guarantee that no two students from the same school would end up in the same group (i.e. that schools with more students, and hence more difficult to place, would get their students assigned first).

For completeness, Table 2 presents a brief overview of the schools involved.

Appendix B: Instructions

Participants in each session spent the entire time of the experimental session sitting in circle in the same room. In order to limit communication to the phases designed for this (see Sect. 2.1), subjects were, since the beginning, instructed not to talk among them about the experiment, and to direct any question to the experimenter in charge of explaining the activity (the experimenter was always the same across all sessions). For the same reason, instructions and control questions were not provided in written form, and were instead verbally issued (in Italian).

-

Initially, subjects entered the room together. The experimenter and a helper (the same across all sessions) were present. A number of chairs, one for each participant, were distributed in circle around the room, except for a portion of one wall, where a table was placed, holding the material used for the experiment. Such material included a computer connected to a projector (where no image was projected initially), the playing cards, and an empty box with a small opening in its top.

“On each of these chairs you will find a note with a name written on it: please find your name and sit on the corresponding chair. Please do not discuss this game with other participants until its end. If you have any questions, please ask them to me. You can do so at any time.”

-

After all participants had sat down, the playing cards used for communicating their decision were distributed, according to a predefined random mapping. The helper went distributing the cards in circle, verifying the names of participants against the list he had.

“My colleague will now assign four cards, covered, to each of you. We will explain you in few moments what use you will make of these cards. It is important that they remain secret: one basic rule of this game is that nobody, at no time, must see your cards.”

-

After all playing cards had been distributed, the functioning of the activity was explained.

“Please now look at your cards, while keeping their face hidden from the view of other participants. You will notice that you have two cards with a red suit, and two with a black suit. The red cards are worth one point, the black cards are worth zero points. You will also notice that the two cards of a black suit come from different decks: one has a blue back, one has a red back. The same applies to the cards of a red suit.”

“The game will be composed of several rounds. At each round, we will collect two cards, covered, from each of you. You all have the possibility, and can freely decide, to give zero, one or two cards from a red suit, that is, to contribute zero, one or two points. The points you will not contribute will remain to you. Please give one card with a blue back and one with a red back.” “Although their composition is, at this point, unknown to you, participants in this room have been subdivided in four groups of approximately the same size. The points you decide to contribute when we collect the cards will flow into a common fund—one for each group. The content of this fund will be multiplied by two and subdivided in equal shares between members of the group. So, at the end of each round, each of you will obtain the points he or she decided to keep, plus the total number of points that your team members decided to contribute, multiplied by two, and divided by the number of team members.”

-

Subjects were then proposed the following three test questions in order to ensure they had correctly understood. For each question, after one or more participants had answered correctly, the experimenter would explain the answer to all participants, and the steps (calculations) required to obtain it.

-

1.

“Let us assume that you are in a group of four people and that, at a given round, each of you decides to keep both points: how many points does each of you get for that round?”

-

2.

“What if, in this same group, each of you decides to contribute both points?”

-

3.

“What if in this same group you decide to keep both points, but the three other group members decide each to contribute both points?”

-

1.

-

Finally, information was given about the rounds and payoffs.

“You now know the basic functioning of the game. The points you make in each round will be added up and, at the end of the game, the three people with most points will win a prize. You don’t know now the number of rounds which you will play, but I will inform you before playing the last round. Moreover, I will provide you with other pieces of information in the following rounds, but details will be provided at that time only.”

-

The experiment then started. Each step of the game was guided by the experimenter. “Now my colleague will pass among you with this box. Please insert in its opening the two cards you decide to give.”

“Now I will register your choices on the computer.”

(Notice that the spreadsheet on which this was done was not shown on the projector screen.)

“Now my colleague will return you your two cards: you can verify they are indeed the two you gave. We can then proceed to the next round.”

-

After the first two rounds, absolute silence was requested:

“From this moment, and until further notice, please abstain from any talking. If you have any question, please raise your hand an I will come and answer it.”

Immediately after, the composition of the groups was revealed, one at a time:

“Please Eeeeee Ffffff, Gggggg Hhhhhh, Iiiiii Jjjjjj and Kkkkkk Llllll now raise your hand. You are members of group X. Please make sure you all identify each other, while remaining silent. Please now lower your hand.”

(notice participants were called by name and surname, while X, the number of the group, was one of A, B, C, or D).

-

After each round starting from the third, information about past contributions was shown on the projector screen (see Fig. 3 for an example referring to round 5).

“These are the average contributions so far: each line refers to a group”

-

After round four, members of each group were invited to discuss among them:

“From now on, you can talk again. Please, members of group A move to this corner of the room, members of group B to this other corner, members of group D to this other corner, and members of group D to this last corner. I will give you exactly two minutes, starting from now, to freely discuss with your group members, then we will proceed with the next round of the game. Remember that it is still forbidden to show your cards to any other participant.”

-

Finally, before round six, subjects were informed that it would be the last round.

“We are now going to play round six, which will be the last round of this game.”

-

A debriefing would follow, in which participants were invited to comment the experiment and the effects of differences across rounds. The experimenter would mention some real world examples of public goods, and comment on the fact that even non-binding mechanisms such as identification and communication can have important consequences on economic decisions made by individuals within societies.

Appendix C: Additional material

Figure 3 features an example of how information about past group contributions was shown to participants (from round 3 onwards).

Table 3 provides some descriptive statistics for participants: for each session, we show the distribution of individual characteristics (geographic origin/gender) based on the assignment of individuals to the treatment. T-tests ran on the each session fail to reject the null of identical distribution between the two categories, with the exception of Session 2 (\(p=0.001\)), in which homogeneous groups were composed only of female participants (we take this into account in Sect. 5.4).

Table 4 provides information about the 12 prize winners (three for each session). For comparison, the minimum possible earning was 2 and the maximum 32 [see Eq. (2)]. The signs of deviations between the shares of winners and the shares of sample presenting each feature are in line with results presented in the main text (females contribute more, although not significantly, “North-only” groups perform better, although not significantly, homogeneous groups perform better).

Appendix D: Supplementary results

1.1 D.1 Analysis of group averages

Table 5 replicates the analysis of phase- and treatment-effects of Table 1 (columns (1) and (2), respectively) at the group, rather than individual, level (analysis of gender and geographic origin is omitted because these characteristics vary within groups).

As a robustness test for results 1 and 2, we also replicate tests presented in Sect. 5, confirming all findings (with the only—unrelated—exception of (HmIII), for which we now obtain \(p=0.137\)).

Figure 4 is the equivalent of Fig. 2, disaggregated at the group level. While variability increases significantly (each point only represents the mean of four to six individual contributions), it allows to observe that all groups are generally increasing , and that no obvious outliers emerge—with the exception of the last round (discussed at the end of Sect. 5.2), in which a few groups drop their contribution levels significantly, as compared to the other groups.

1.2 D.2 Phase-treatment interaction

In what follows, we combine Eqs. 2 and 3, interacting phase and treatment dummies with the geographic origin of participants.

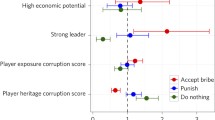

Hypotheses (HdII), (HdIII) and (HdIV) allowed us to investigate whether being in a homogeneous group (instead of a heterogeneous one) has an effect on contributions. The estimation of Eq. (5) can help us verify if there is a treatment effect conditional on the geographic origin of individuals. Namely, we can answer such question by running the following joint tests on coefficients presented in Table 6.

-

\({\mathcal {H}}_0: \zeta ^h_P + \zeta ^{hn}_P > 0\) for individuals from the North,

-

\({\mathcal {H}}_0: \zeta ^h_P > 0\) for individuals from the South,

for each phase \(P=II,III,IV\). From such tests, no significant differences emerge (\(p=0.183, 0.239, 0.259\) for the North, 0.149, 0.517, 0.204 for the South, respectively).

By exploiting the disaggregation along the dimension of geography, we can also compare North-only and South-only groups between them. This is done by testing \({\mathcal {H}}_0: \zeta _P^{n} + \zeta _P^{hn}> 0\) for each phase \(P=II,III,IV\).Footnote 26 Results do not suggest that people from the North act differently from people from the South in homogeneous groups (\(p=0.703, 0.191, 0.306\), respectively).

By running the same analysis for mixed groups, we can instead compare the behaviour of Southerners and Northerners subject to the same treatment (i.e. being in a mixed group) in each phase.Footnote 27 Namely, we test \({\mathcal {H}}_0: \zeta ^{n}_P > 0\) for each phase \(P=II,III,IV\): in line with Result 3, in mixed groups we find a higher level of contributions on behalf of Northeners compared to Southeners, for two phases out of three (\(p=0.669, 0.055, 0.087\), respectively).

In conclusion, while we confirm the higher level of contributions of Northeners (Result 3) in mixed groups, we find no evidence that the treatment effect is related to the geographic origin of subjects. That is, we cannot explain Results 1 and 2 as the consequence of an interaction between the treatment and the geographic origin. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that such “non-result” is due to the low numerosity of observations in each of the subsamples considered.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Battiston, P., Gamba, S. When the two ends meet: an experiment on cooperation and social capital. Econ Polit 37, 911–940 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00184-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00184-7