Abstract

Empirical evidence has shown that people with better self-control to a greater extent have the self-regulatory ability to act in line with their long-term goals. In this pre-registered study, the relationship between self-control and self-regulatory behavior was investigated both directly and indirectly, i.e., through affective forecasting ability. This is of great interest as it is necessary to be able to forecast one’s emotional response to future events in order to make choices that maximize one’s happiness. However, in a laboratory experiment with undergraduate students, I found no evidence of self-control being associated with affective forecasting ability, or that people with better self-control more often acted in a way that maximized their expected happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Every day we make decisions that affect our future. To maximize our happiness, we try to predict our emotional response to what might happen, i.e., our expected emotions. A problem with, and a key feature of, expected emotions is that they are experienced only when the outcome of the choice has taken shape. Thus, to act in a happiness-maximizing way, we must first be able to forecast our emotional response to future events; this is known as affective forecasting (Rick & Loewenstein, 2008), and second, have the self-regulatory ability needed to make the choices that maximize our expected future happiness.

According to economic theory, the rational individual will always choose the utility-maximizing option, independent of the setting. However, most of us are not homo economicus (Tinghög, Barrafrem, & Västfjäll, 2022) and will, therefore, sometimes face conflicts between immediate gratification and long-term goals. Often has self-regulation been put forward as key to manage goal-directed behavior (Hoyle & Moshontz, 2018). Hoyle and Moshontz (2018) identified several individual differences, including self-control, beliefs and expectations, optimism, emotions, and delay of gratification, which affect one’s ability to progress towards and achieve goals. Building on their model, the current study will focus on the correlation between self-control, self-regulatory behavior, and affective forecasting, while also controlling for optimism and delay of gratification.

Many decisions include an intertemporal element where we face a trade-off between an option that generates immediate gratification and another option that leads us towards our long-term goals, e.g., staying in and eating candy is rewarding now, but going for a run is, in most cases, better if your long-term goal is to live a long and healthy life. Self-control has often been put forward as an important ability when it comes to resisting temptation to reverse long-term plans (see, e.g., Berns et al., 2007; Thaler & Shefrin, 1981). Previous studies have shown that people high in self-control are more likely to avoid behaviors that are inconsistent with their long-term goals and pursue their goals even when bored or when motivation is low, which means that people with higher levels of self-control tend to be more effective at behavioral self-regulation (Hoyle & Moshontz, 2018). This has been formalized in the two-self model, which tries to explain self-control problems as an ongoing conflict between a farsighted planner and myopic doers that coexist within every individual at every point in time (Thaler & Shefrin, 1981). The farsighted planner is assumed to care about lifetime utility while the myopic doers only care about the short term.

Affective forecasting is another important factor in all intertemporal choices. Affective forecasting has been defined as “people’s ability to forecast their own feelings,” (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003, p. 346), but despite this, affective forecasting has, to my knowledge, not been studied in relation to self-regulation or self-control. Instead, most previous studies on affective forecasting have focused on how good people are at forecasting their future emotions to outcomes in risky gambles and whether the discrepancy between expected and experienced emotions is caused by overestimation of some emotions or underestimation of others (Buehler & McFarland, 2001; Kermer et al., 2006; Tochkov, 2009). Bertoni and Corazzini (2018) found that overestimating one’s future well-being was negatively correlated with subsequent well-being levels, which implies that affective forecasting ability could affect a person’s general well-being too.

The aim of this study is to investigate if self-control correlates with the ability to pursue towards one’s long-term goals both directly, as suggested by Hoyle and Moshontz (2018), and indirectly, through affective forecasting. The line of argument would, in the second case, be that if a person is better at listening to his or her inner farsighted planner, future emotions might be more salient as well, which would make affective forecasting easier. In addition, without a correct estimation of one’s affective response to different outcomes, making an informed choice to maximize one’s future happiness is close to impossible. To study this, an incentivized, pre-registered,Footnote 1 two-step laboratory experiment was conducted. In the first step, self-control was assessed by the Brief Self-Control Scale (Tangney et al., 2004) and the participants were asked to forecast their emotional responses to monetary gains occurring on different days over a period of six months. As a second step, the participants made intertemporal choices using the same amounts and time horizons as in the first task. One of the choices was later materialized and the participants were asked to report their actual emotional response upon receiving the money. Using the participants’ stated expected emotions from step 1, it was possible to study to what extent the participants chose the options in the intertemporal choice task that would maximize their expected happiness. Hence, the design made it possible to evaluate both the participants’ self-regulatory and affective forecasting abilities. The result, however, showed no relationship between self-control and self-regulatory ability, neither directly through respondents choosing the intertemporal choices that maximizes their expected happiness, nor indirectly through a positive correlation between affective forecasting ability and self-control.

2 Methods

Participants were 178 undergraduate students (110 men and 68 women) at Linköping University and Stockholm University. Their average age was 25 years (SD = 5.30, range = 19–59). All participants were recruited via ORSEE (Greiner, 2015). The experiment was computer-based and one to ten students participated in each session. The experiment contained two parts, spread over different days, and every participant had to attend both parts.Footnote 2 Three observations were excluded from the affective forecasting part of the study since the participants failed to show up for the second part.

2.1 Material and procedure

Participants conducted part 1 at time t and were randomly assigned to conduct part 2 at either time t + 1 day or t + 7 days. For part 1, the participants performed several tasks on a computer for approximately 15 min. They were asked to predict how happy, pleased, sad and disappointed they would feel if they were occasionally given different sums of money over the next six months (for instance, “At the time of the payment, how happy would you feel if you would get SEK 150 in seven days?”). They gave their answers on unmarked lines anchored at not at all happy/pleased/sad/disappointed and very happy/pleased/ sad/disappointed. (For scoring purposes, the lines were transformed into 21 units.) Although data on sadness and disappointment were collected, only happiness and pleasure were used in the analysis since all transactions were gains and the variation in the negative emotions was low (sad: M = 0.83, SD = 1.99; disappointed: M = 1.81, SD = 3.02). All participants were asked to make affective forecasts for 24 scenarios.

In the second step, the participants made nine hypothetical intertemporal choices followed by four incentivized ones, where the participants knew that one of the four decisions would be randomly selected for actual payment. For the hypothetical choices, the small delayed reward trials from Kirby et al. (1999) were adopted as they corresponded most closely to the incentivized trials. The amounts and time horizons appearing in the intertemporal choices were the same as those in the affective forecasting task. The hypothetical choices were used to calculate each participant’s discount factor (k-value). Across all participants, the geometric mean value of k was 0.018 (SD = 0.027), which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Duckworth & Seligman, 2006; Kirby et al., 1999). In the incentivized trials, participants were asked to choose between a smaller reward today and a larger reward tomorrow or in a week. Since hypothetical and incentivized trials could yield different results (Clot et al., 2018), those results were later analyzed both separately and aggregated.

Thereafter, the participants filled out three scales measuring individual differences. To measure self-control, the aggregated mean value of the Brief Self-Control Scale (Tangney et al., 2004) was used (M = 3.24, SD = 0.61, range 1.69–4.77). The participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all like me and 5 = very much like me, the extent to which the 13 statements corresponded to their behavior (e.g., “Sometimes I can’t stop myself from doing something, even if I know it is wrong.”). The Cronbach’s alpha of the Brief Self-Control Scale was 0.81 in this sample, which indicate high internal consistency. To assess the respondents’ life satisfaction the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) was used (M = 23.71, SD = 5.90, range 5–35). To measure their optimism, the participants were asked to fill out the Revised Life Orientation Test (M = 3.47, SD = 0.82, range 1–5) (Scheier et al., 1994). In addition, demographic information about the participants was collected, including their sex, education, university, age, and monthly income.

Lastly, the participants were informed about which of their incentivized choices would be realized. If the participant had chosen the immediate reward for that choice, he or she was asked to indicate on a similar scale as in the beginning of the session how happy, pleased, sad and disappointed he or she had felt when receiving the money. If the participant had chosen to wait for his or her reward, he or she did not have to answer a question about how they felt. Depending on which incentivized choice was assigned, the participant had to schedule part 2 of the experiment either 1 or 7 days after part 1.

In part 2, the participants who had chosen the delayed payment were asked how happy, pleased, sad and disappointed they felt when the money was given to them. Those who received their payment in the first part were asked how happy, pleased, sad and disappointed they felt right now, with no reference to their payment. Thereafter, all participants completed a filler task which took about 5 min. All participants had to attend both parts of the experiment to keep the transaction cost of the two outcomes in the intertemporal choices as equal as possible.Footnote 3 If only those who would receive the delayed reward had had to come back, the cost for choosing that option would have been much higher than for the option of receiving money today, which could have skewed the results.

2.2 Regression analysis

To investigate if self-control, or any of the other psychological traits or socio-demographic characteristics, correlated with the ability to predict one’s future emotions, a couple of regression analyses were run. The specification was

In the first setting, Y was the difference between experienced and predicted happiness for the realized scenario, expressed in absolute numbers. Therefore, if a participant predicted that SEK 100 today would generate a happiness score of 15 and later reported that it generated a happiness score of 10, the prediction error was 5. SC was the average score on the Brief Self-Control Scale, X was a vector including all control variables: income, sex, age, time preferences, the time delay between predicted and experienced emotions, optimism, and life satisfaction. Income was divided into four categories: below SEK 6000/month, SEK 6000–10,999/month, SEK 11,000–16,000/month and more than SEK 16,000/month. These categories were chosen with regard to the Swedish student loan system. Time preferences were expressed in terms of k-values (Kirby et al., 1999). All k-values were multiplied by 10 to make them more interpretable in an OLS-setting. The delay consisted of two dummies, one for the participants who received their compensation the day after the first part and one for those who received their compensation one week after the first part. Optimism was measured as the average score on the Revised Life Orientation Test (Scheier et al., 1994) and life satisfaction as the total score of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985). The model was estimated using OLS with robust standard errors. In the second setting, the model was identical, apart from the dependent variable being the prediction error in pleasure instead of in happiness.

To investigate if self-control was associated with a higher number of happiness-maximizing choices, an identical model as the one above was used, except that the dependent variable was the number of choices that maximized the expected happiness in the intertemporal choice task. A participant was assumed to act in an expected happiness-maximizing way if he or she picked the alternative in the intertemporal choice task that corresponded to the highest expected happiness stated in the affective forecasting part of the experiment. For instance, a participant who has stated her expected happiness of receiving 100 SEK today to be 10 and her expected happiness of receiving 150 SEK in one week to be 9 was maximizing her expected happiness if she chose the immediate reward in a choice between 100 SEK today or 150 SEK in one week. The dependent variable could, therefore, take all discrete values between 0 and 13. The vector with control variables included income, sex, age, time preferences, optimism, and life satisfaction. Since everyone conducted this task during the first part of the experiment, there was no need to include a dummy for the time delay and all 178 participants could be included.

3 Results

3.1 Affective forecasting and self-control

The prediction errors (i.e., the difference between experienced and predicted emotion) for happiness and pleasure, respectively, were fairly normally distributed and hovered around zero. Hence, on an aggregate level, the participants did not over- or underestimate their positive emotions in any systematic way. Another concern was that the participants’ happiness would depend on which intertemporal choice was realized. A participant who always chose to wait would earn between SEK 120 and SEK 250, while a participant who never waited would receive between SEK 100 and SEK 170. A participant receiving a lower payment may, therefore, be less happy with her payment when she compared it with what she could have earned if she had been luckier, than she predicted at the beginning of the experiment, when not comparing. This could lead to forecasts overestimating happiness for the lower payment and possible underestimation of happiness for higher payments. However, a one-way ANOVA found no difference in prediction error, expressed in real numbers, between groups assigned to different payments, F(3,171) = 1.13, p = 0.338. Therefore, in the analysis below, I will only investigate the absolute value of the prediction error and ‘prediction error’ should, therefore, always be read as referring to the absolute value.

The average participant predicted his or her happiness to be 12.74, and his or her pleasure to be 11.99 on a scale from 0 to 20. Table 1 shows the prediction errors sorted by the different time delays. A one-way ANOVA showed that the affective forecasting errors for happiness did not change in any systematic way as the time horizon expanded, F(2,172) = 1.68, p = 0.190, neither did it for pleasure, F(2,172) = 2.54, p = 0.082.

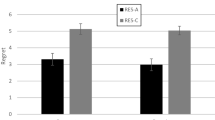

To investigate whether people with more self-control were better at forecasting their future emotions, the sample was divided into two groups by a median split of the self-control variable. A median split was suitable since the variable was approximately normally distributed with values between 1.7 and 4.8. All participants scoring 3.2 or higher on the Brief Self-control Scale were considered to have high self-control, everyone else was considered to have low self-control. The average prediction error for happiness among participants with high self-control was 3.33 (SD = 3.13), while the average prediction error for pleasure was 3.29 (SD = 2.91). For participants with low self-control, the corresponding prediction errors were 3.75 (SD = 3.30) for happiness and 3.41 (SD = 3.46) for pleasure. T-tests showed that there was no significant difference between people with higher and lower levels of self-control when it came to predicting future happiness, t(173) = 0.867, p = 0.387, as well as when it came to predicting future pleasure t(173) = 0.241, p = 0.810. These results were robust also when splitting the sample differently. When comparing the 25% of the participants with the highest self-reported self-control (n = 53) with the 25% of the participants with the lowest (n = 42), there was no statistically significant difference between their prediction errors in either happiness, t(93) = 0.109, p = 0.914, or in pleasure, t(93) = 0.042, p = 0.967.

Since the participants’ self-control did not seem to affect their ability to forecast future emotions, the next step was to investigate if other individual differences or demographic variables more accurately predicted this ability. I modeled the relationship between the individual differences and affective forecasting by running OLS regressions with robust standard errors. In the regressions, each participant’s average score on the Brief Self-Control Scale was used as a continuous variable. The results are shown in Table 2. Participants with higher income were worse at predicting their future happiness, and no other individual differences measured in this study were significantly associated with affective forecasting ability.

3.2 Self-regulation and self-control

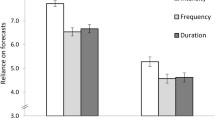

I now turn to the second research question: if people with higher levels of self-control are more likely to choose the option that corresponds to the highest predicted happiness in the affective forecasting task, which I would interpret as having higher self-regulatory ability. The intertemporal choices were divided into two categories: the nine that were hypothetical and the four that were incentivized. The average number of expected happiness-maximizing choices was 7.29 (SD = 1.32, range 3–9) for the hypothetical choices and 2.87 (SD = 0.99, range 0–4) for the incentivized ones. As can be seen in Table 3, the vast majority chose to delay their rewards in all four incentivized trials.

Thereafter, a median split of the self-control variable was made, and t-tests were used to determine if there was a difference between people with high and low levels of self-reported self-control when it came to picking the alternative that would maximize their expected happiness. No such difference was observed in the hypothetical choices, t(176) = 1.717, p = 0.088 (Mhigh self-control = 7.13, Mlow self-control = 7.47), or the incentivized choices, t(176) = − 0.930, p = 0.354, (Mhigh self-control = 2.93, Mlow self-control = 2.79).

According to these t-tests, self-control did not seem to be associated with the number of happiness-maximizing choices. To see if any of the other individual differences that were measured in this study had a greater impact on decision making, OLS regressions with the number of expected happiness-maximizing choices as the dependent variable were run. Once again, self-control was used as a continuous variable in the regression models. As Table 4 shows, only time preferences correlated with the number of happiness-maximizing choices. However, the results were inconclusive as impatience had a positive effect on the hypothetical choices, but a negative effect on the incentivized ones. The same results were found in regression analyses where adjusted k-value was the only independent variable.Footnote 4 Hence, the observed difference in signs is not caused by multicollinearity and as I find no other theoretical explanation to this, I will suggest it to be interpreted as nothing but a false positive.

4 Discussion

This study set out to investigate if self-control was associated with self-regulatory behavior, both directly or through affective forecasting ability. Although the vast majority of previous research has found that self-control positively correlates with one’s ability to achieve long-term goals (Achtziger et al., 2015; De Ridder et al., 2012; Moffitt et al., 2011; Wyss et al., 2022), this study showed no support for a correlation between self-reported self-control and choices that maximizes the respondents’ long-term happiness. In addition, I found no support for self-control correlating with affective forecasting ability, which is less surprising as the correlation between self-control and affective forecasting ability is underexplored.

In this study, self-control was measured by the Brief Self-Control Scale. Apart from self-reported self-control, the respondents’ impatience with intertemporal choice tasks, the k-value, was also assessed. This measure has been used as a proxy for self-control in other studies (Pyone & Isen, 2011; Rachlin & Green, 1972), but the link between self-control and impatience has rarely been tested (Delaney & Lades, 2017). In this sample the correlation between self-reported self-control and k-value was as low as − 0.0076. One possible explanation for this is that self-reported measures encourage the participants to reflect upon their general behavior in life, while behavioral measures, such as intertemporal choices, reflect the participants’ actual behavior in a specific, highly structured situation (Dang et al., 2020). In the current study, self-reported self-control did not correlate with expected happiness-maximizing behavior, but the participants’ k-value did. However, as the k-value was negatively associated with the number of expected happiness-maximizing choices in the incentivized setting and positively associated with it in the hypothetical choices, the result must be interpreted with caution as it may just as well be a false positive.

A surprising finding in this study is how good the respondents were at forecasting their emotional response to future events. Compared to similar studies, this study made the affective forecasting task more challenging in two ways. First, the time that elapsed between the prediction and the actual reported outcome was longer for most participants than it was in some other laboratory studies (e.g., Kermer et al., 2006; Mellers & McGraw, 2001). Second, the participants rated their emotions on unmarked scales to prevent them from applying hindsight to their predicted emotions and achieve accuracy of their prediction by choosing the same value for their experienced emotions. Still, in this sample, the magnitude of the affective forecasting errors did not increase with longer time horizons which would be reasonable to expect if the respondents intentionally tried to remember their forecasts when reporting their experienced emotions. Apart from the desire to answer “correctly” when reporting their actual emotional response, a measure of self-reported emotions is vulnerable to participants’ limited access to their experience of emotions or their inability to transform their experience into scale measures (Västfjäll, 2010). However, that is less of a problem in this study since the magnitude of the emotions is outside of its scope.

When the unmarked scales were transformed into 21-point scales, I found an average affective forecasting error of 3.52 for happiness and 3.35 for pleasure. This relatively small affective forecasting error could be attributable to the design of the study. Buehler and McFarland (2001) found that people made accurate estimations of their emotional reactions to expected outcomes, but they overestimated their emotional reactions to unexpected ones. Intertemporal choice tasks involve no element of risk and must, therefore, be considered expected outcomes. In addition, Kermer et al. (2006) showed that people were better at predicting their emotional response to different outcomes in games where they won money than when they lost.

An important note is that this study focuses on happiness—instead of utility-maximizing choices, as the utility-maximizing option for a person by definition is revealed by the choice he or she makes (Kimball & Willis, 2006). Theoretically, utility also includes other aspects than one’s own happiness or well-being, e.g., the happiness of others, freedom of choice, and financial and physical security (Benjamin et al., 2014), which is not assessed in this study. Still, in such extremely formalized and structured choices that the respondents of this study faced, these other aspects of utility should not play a significant role for the decision maker, which makes it possible to argue that happiness is a good proxy for utility in this specific case.

As all studies, this study has some weaknesses that should be discussed and addressed when future studies are designed. First, in the incentivized choices, even the delayed option would happen in the near future. The longest delay was 7 days, which can be seen as relatively soon. Second, there was quite a difference between the small and the large amounts paid, since I wanted the participants to experience a difference in emotional reaction. These two things might explain why most of the participants chose the delayed reward in the incentivized choices. Possibly, even impatient participants were willing to wait a week to receive more money. This could possibly increase the likelihood of the participants choosing the option that maximizes their stated happiness, but it should not impact how well they could forecast the magnitude of their future emotions (i.e., the prediction errors). Another possible experimental design issue is that people who have the planning ability to participate in an experiment spread over several days have a certain amount of self-control. Therefore, using this design, I exclude people with the lowest levels of self-control, which is problematic given the objectives of the study. Further, when making decisions, the participants might also have taken anticipatory emotions into account. For example, everyone knows that looking forward to a vacation can be almost as pleasant as the vacation itself. In this paper, I did not take anticipatory emotions into account, but they might partly explain the observed patience in our sample, and why some participants were willing to wait although they stated that receiving the larger amount later would generate less happiness.

In summary, I found no relationship between self-control and self-regulatory ability, neither directly through respondents choosing the intertemporal choices that maximizes their expected happiness, nor indirectly through a positive correlation between affective forecasting ability and self-control. If such a relationship still exists, the size of the effect should be small in this sample, as a sensitivity power analysis showed that this design would make it possible to detect small to medium-sized effects.Footnote 5 As this study was limited to monetary gains, it would be interesting to investigate if the results would hold even for monetary losses. Further studies should also investigate if the results were driven by the lack of uncertainty in intertemporal choice tasks and if the results would replicate with a non-student sample.

Data availability

Materials, and data can all be accessed through the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/fswkr/.

Notes

All instructions can be found in the Online Appendix.

If a participant did not show up on the scheduled time for part 2, they were called and asked to show up later the same day.

See Table A1 in the Online Appendix.

References

Achtziger, A., Hubert, M., Kenning, P., Raab, G., & Reisch, L. (2015). Debt out of control: The links between self-control, compulsive buying, and real debts. Journal of Economic Psychology, 49, 141–149.

Benjamin, D. J., Heffetz, O., Kimball, M. S., & Szembrot, N. (2014). Beyond happiness and satisfaction: Toward well-being indices based on stated preference. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2698–2735.

Berns, G. S., Laibson, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2007). Intertemporal choice–toward an integrative framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(11), 482–488.

Bertoni, M., & Corazzini, L. (2018). Asymmetric affective forecasting errors and their correlation with subjective well-being. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0192941.

Buehler, R., & McFarland, C. (2001). Intensity bias in affective forecasting: The role of temporal focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(11), 1480–1493.

Clot, S., Grolleau, G., & Ibanez, L. (2018). Shall we pay all? An experimental test of Random Incentivized Systems. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 73, 93–98.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Dang, J., King, K. M., & Inzlicht, M. (2020). Why are self-report and behavioral measures weakly correlated? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(4), 267–269.

De Ridder, D. T., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., Finkenauer, C., Stok, F. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(1), 76–99.

Delaney, L., & Lades, L. K. (2017). Present bias and everyday self-control failures: A day reconstruction study. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 30(5), 1157–1167.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. (2006). Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 198–208.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Hoyle, R. H., & Moshontz, H. (2018). Self-regulation: An individual difference perspective. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/g25hx

Kermer, D. A., Driver-Linn, E., Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2006). Loss aversion is an affective forecasting error. Psychological Science, 17(8), 649–653.

Kimball, M., & Willis, R. (2006). Utility and happiness. University of Michigan, 30, 1.

Kirby, K. N., Petry, N. M., & Bickel, W. K. (1999). Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128(1), 78–87.

Mellers, B. A., & McGraw, A. P. (2001). Anticipated emotions as guides to choice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 210–214.

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., & Ross, S. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698.

Pyone, J. S., & Isen, A. M. (2011). Positive affect, intertemporal choice, and levels of thinking: Increasing consumers’ willingness to wait. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(3), 532–543.

Rachlin, H., & Green, L. (1972). Commitment, choice and self-control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 17(1), 15–22.

Rick, S., & Loewenstein, G. (2008). The role of emotion in economic behavior. Handbook of Emotions, 3, 138–158.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078.

Tangney, J., Baumeister, R., & Boone, A. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324.

Thaler, R. H., & Shefrin, H. M. (1981). An economic theory of self-control. Journal of Political Economy, 89(2), 392–406.

Tinghög, G., Barrafrem, K., & Västfjäll, D. (2022). The good, bad and ugly of information (un) processing: Homo economicus, homo heuristicus and homo ignorans. Journal of Economic Psychology, 2022, 102574.

Tochkov, K. (2009). The impact of emotions on problem gambling. American Journal of Psychological Research, 5(1), 7–19.

Västfjäll, D. (2010). Indirect perceptual, cognitive, and behavioural measures. In P. N. J. J. A. Sloboda (Ed.), Series in affective science. Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 255–277). Oxford University Press.

Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2003). Affective forecasting. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 345–411.

Wyss, A. M., Knoch, D., & Berger, S. (2022). When and how pro-environmental attitudes turn into behavior: The role of costs, benefits, and self-control. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 79, 101748.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Daniel Västfjäll, Ali Ahmed, Gustav Tinghög, Martin Svensson, Erik Mohlin, Markus Selart, Thérèse Lind, and participants at the Nordic conference on behavioral and experimental economics 2018 for valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. I also want to thank David Andersson for helping with statistical matters, and Kajsa Hansson and Per Andersson for assisting the data collection.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strömbäck, C. Forecasting emotions: exploring the relationship between self-control, affective forecasting, and self-regulatory behavior. J Econ Sci Assoc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-024-00173-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-024-00173-7