Abstract

Regret aversion often compels individuals to undertake extensive searches before making a choice. Yet, donors hardly search among charitable alternatives prior to giving. It is unclear if donors search little because there is no regret to avoid as they rarely learn the outcome of their donations, or they simply do not care as donation outcomes do not directly impact them. To investigate if absence of regret is a contributing factor behind this lack of search, the current study develops an online experiment wherein subjects can research available charities before donating. While the control group does not receive any regret-inducing feedback (such as relative effectiveness of their donation) ex-post of decision-making, the treatment group is ex-ante aware of receiving charity rankings ex-post. While the control subjects donate without gathering information on charities, the treatment subjects research substantially more and consequentially donate to better ranked charities without decreasing donations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Interview-based reports indicate that only 3% of donors claim to do any research on charities before giving.Footnote 1 In conjunction with the magnitude of existing charities, this suggests a large amount of inefficient allocations.Footnote 2 These reports speculate “warm glow” (Andreoni, 1989) to be the main reason behind the lack of search among donors.Footnote 3 This study explores a complimentary factor: regret. Due to the credence nature (Darby & Karni, 1973) of charities, donors rarely learn the outcome of their charitable contributions causing them to rarely regret poor decisions.Footnote 4 For instance, if the consumer anticipates feedback, such as learning the quality of food at the chosen restaurant and comparing it with nearby restaurants, she will search more to avoid feeling regret. However, if the consumer anticipates no feedback, such as never learning a charity’s quality in terms of its impact per dollar, then she will not search as exhaustively because there is no regret to avoid. Therefore, this study investigates if absence of post-decisional, regret-inducing feedback on the relative effectiveness of one’s donations is a contributing factor behind this lack of search among donors in charitable giving.

Prior studies have shown that receiving feedback generates regret in decision making, thereby altering behavior ex-ante.Footnote 5 Using a sequential search framework in a context-free experience good environment, Jhunjhunwala (2021) confirms that such feedback results in increased search, motivating the current study to investigate if its replicable in the charitable giving environment, providing insights on the prevalence of uninformed charitable giving. Prior findings are not guaranteed to unfold in this setting as donor decisions do not impact themselves directly. Furthermore, presence of such feedback could dissuade donors from donating altogether to avoid regret.Footnote 6 However, this study shows that the anticipation of post-decisional, regret inducing feedback has a positive effect on search intensity in charitable giving, without hurting the extensive and intensive margins of donations. Thus, as its main contribution, this analysis provides insights into why donors search so little among charitable alternatives prior to giving: the general absence of feedback on one’s contributions, relative to alternatives, eliminates the potential to regret one’s donation decisions and renders charity information non-instrumental for donors ex-ante.

To study the above, I develop an online experiment with real charities as options where subjects can get free, detailed information on these charities sequentially to infer their quality prior to donating. While the control group receives no feedback, the treatment group is ex-ante aware of receiving post-decisional feedback in the form of charity rankings as determined by third-party evaluations. Consequentially, they research more options relative to the control group prior to donating. Upon seeing the rankings, the subjects expressing regret in their decision increase their search intensity and donate to better ranked charities. The continued lack of search among the control subjects provides evidence that the absence of feedback can partially explain the observed lack of search among donors in the real-world. Importantly, the provision of such feedback had no impact on donation levels.

While this study contributes to the role of information in charitable giving literature broadly, it specifically documents how presence of post-decisional feedback affects donor search for optional, pre-decisional information. Prior studies, on the other hand, have investigated the effect of mandatory, pre-decisional information provision and its saliency on donation levels. Most find that providing donors with statistical information mitigates generosity and dampens donations altogether, unlike the findings here. Such information can lead one to develop excuses to not give (Exley, 2015, 2020) or due to moral licensing (Goette & Tripodi, 2020).Footnote 7 It can also increase giving if a charity turns out to be better than previously thought (Butera & Horn, 2020). Or, it may have no impact on the overall giving but produce significant heterogeneity (Karlan & Wood, 2017). A conjecture for finding no difference in donation levels in the current study could be attributed to the inherent nature of the question asked. Most studies investigate donations to a charity that they provide impact information on. Conversely, choosing among charities in the presence of relative information may enhance an option’s appeal, diverting donations to it instead of altering donation levels.

Among studies investigating behavior on obtaining relevant information prior to giving, Fong and Oberholzer-Gee (2011) find that only 1/3rd of dictators in the standard dictator game pay to learn more about their recipient. Similarly, Null (2011) manipulates the social impact of donations per charity making this information available for purchase before decision-making but finds that individuals are unwilling to pay for it. Besides being costly, subjects in Null (2011) do not find out how their decision compares to an alternative—two key differentiating aspects of the current study, which demonstrates that only when mandatory regret-inducing, post-decisional information is provided, the optional (and free) pre-decisional information becomes instrumental in decision-making.

Overall, this study investigates empirically if absence of regret-inducing feedback on relative effectiveness of one’s donations is a contributing factor behind uninformed donations, and indeed finds support for it. The nature of the question—essentially testing a factor absent in the real-world to be a cause behind an observed phenomenon—makes real-world investigation with adequate controls practically unfeasible. Therefore, a controlled experiment with real charities emerges as a suitable alternative.

2 Experimental design

The experiment was conducted online using Qualtrics. Ohio State University undergraduates on the lab database were randomly invited to participate in a survey, estimated to last for ∼ 7 min. As in Coffman (2016), a lottery was used to incentivize subjects wherein for every 40 subjects who completed the survey, one subject was chosen randomly to win $80. Each participant had to decide in advance how they would distribute the $80 between a charity and themselves. Conditional on winning the lottery, their decision would be automatically implemented. The survey comprised of two identical rounds where one round per winner was selected randomly for implementation.

In each round, the subjects were given four charities to choose one from, each benefiting poor communities in Africa. These options differed across rounds but were the same across subjects. Subjects were informed that the charity names were altered to keep them anonymous. This feature rules out mere-exposure effect (Zajonc, 2001) as a reason to support a particular charity. While the charities differed in their techniques, the beneficiary group at a broader level remained unchanged. This prevented subjects from supporting a charity based solely on its cause. The four charities in round 1 were Against Malaria Foundation, The Lunchbox Fund, Hands for Africa, and Madaktari Africa, and those in round 2 were Give Directly, Aqua Africa, Develop Africa, and Africa Development Promise.

Using a between-subjects design, subjects were divided into two groups: control and treatment. Subjects in both groups were exposed to the same charities, in the same order, with the same pseudonyms. Both groups were given the option to gather information per charity prior to making a donation decision. The treatment group subjects were informed ex-ante that conditional on donating, they’d be shown the real names of all four charities and their rankings based on their performance as evaluated by third-party ratings.Footnote 8 The conditional nature of feedback provision was motivated by the fact that in the real-world, relative to non-donors, donors are more likely to come across information about the charities they support, thereby causing them to reevaluate their future donation decisions.Footnote 9

The ranking was utilized to examine whether its provision, ex-post of decision-making, renders the available charity information instrumental ex-ante, since prior studies (Null, 2011) found such information to be non-instrumental in the decision-making process. Therefore, the experiment utilizes 2 key measures that donors seem to find valuable as performance metrics to rank charities: third party ratings (Brown et al., 2017; Yoruk, 2013) and financial information including overhead costs (Hope Consulting, 2012).Footnote 10 Out of the 8 charities used in this experiment, there were 2 top charities (one per round), designated so by third-party charity evaluators. These charities were ranked #1 in the ranking feedback: Against Malaria Foundation in round 1 and Give Directly in round 2. The other 6 charities were ranked based on multiple factors such as external validation, amount spent on cause (the 2 top-charities spent over > 90% on cause), donation trend, and self-reported impact information.Footnote 11 Ultimately, the subjects were not required to follow these rankings.

Each round can be divided into 3 stages: (1) information gathering stage, (2) donation decision stage, and (3) feedback stage. After consenting to participate and reading the basic instructions, the subjects entered the information gathering stage. They were presented with the mission statements of all four charities in round 1. They then had three options to choose from: know more about these charities sequentially, go to the donation page to donate to any one of them, or not donate at all and end the round. Choosing to ‘know more about a charity’ took them to a page where financial information and reviews of the chosen charity were available (essentially the information that was used in the rankings). The subjects could terminate the information gathering stage at any point as they had the latter 2 options always available. Choosing to ‘go to the donation page’ brought them to the donation decision stage of the round where they decided how much of the $80 to donate to any one charity of their choice.

After making their donation decision, subjects who made a positive donation in the treatment group entered the feedback stage where they received the ranking mentioned above. Conditional on donating to the top charity, they were asked how they felt about their donation, with their options being ‘indifferent’, ‘good’, or ‘accomplished’. Conditional on not donating to the top charity, they were asked if they wished they had done better and their options were ‘I don't care’, ‘I did my best’, ‘I could have done better’, and ‘Yes, I really wish I had done more’. These questions served as a measure of their rejoice and regret intensity, respectively. The main survey ended after the subjects in the treatment group completed the regret elicitation question for round 2. In contrast, the control group received no feedback, with the donation decision stage being the last stage of each round. While round 1 is enough to see the effects of anticipated regret, round 2 serves an important purpose. Since donating to charities does not impact an individual directly, it is possible that one does not internalize the full impact of receiving feedback in such a setting. Nevertheless, this feedback can influence their future search behavior and donation levels. It is unclear if it would encourage individuals to actively seek out better-ranked charities or deter them from donating altogether to avoid potential regret. Round 2 enables the examination of these effects.

3 Results

A total of 484 subjects participated, half in treatment and half in control. Of these, 21 in control and 26 in treatment chose “I do not want to make a donation” option at the start of both rounds without reading any of the mission statements. These subjects, termed “non-donors”, are dropped from all analyses as there is no data on their search behavior or their donation levels resulting from engaging in the search process for either of the two rounds. This section is divided into 3 parts, with each part reporting results associated with the three main variables of interest: search, charity donated to, and donation levels.Footnote 12

3.1 Increased ex-ante search in the presence of feedback

Figure 1 displays the frequency distribution of number of charities searched in rounds 1 and 2 across groups. Those who searched zero charities likely donated based on mission statements alone. In round 1, 16% of subjects searched all four charities in the treatment group while only 9% in the control. This difference is significant (p value < 0.05, using chi-square test) and renders the two distributions marginally significantly different (p value < 0.1). In round 2, this percentage increases to 43% in the treatment group, while hovers around 10% in the control. Moreover, while only 41% of the subjects searched all four charities in the treatment, 73% searched all four in the control, making round 2 distributions significantly different across groups (p value < 0.01).Footnote 13

Charities Searched prior to Donating. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, using chi-square test. In addition to the 47 “non-donors”, 12 (9) subjects in round 1 and 11 (10) subjects in round 2 of control (treatment) acted such as non-donors. These are, therefore, excluded in this figure depending on the round. Including them causes no significant changes to the results. Observations—round 1: 209 control, 207 treatment; round 2: 210 control, 206 treatment

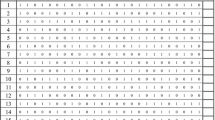

To better understand the impact of feedback on search, Table 1 presents two regression models, with and without controls. The models display a significant treatment effect and a significant gender effect, with males searching less than females. The significant interaction coefficient between treatment and round 2 shows that subjects in the treatment group search significantly more in round 2 Lastly, as expected, there is a strong positive correlation between donation levels and search levels, i.e., those who donate more tend to search more.Footnote 14

One can only speculate why the difference in search behavior across the two groups was marginal in round 1 but substantial in round 2—possibly because one did not internalize the full impact of receiving feedback initially, altering future behavior in favor of search. Thus, I investigate elicited regret responses considering the behavior observed in round 1, and how it impacts behavior in round 2. It is natural for one’s regret intensity to increase with worse outcomes. The distribution of regret over charities (Fig. 11, Appendix 2) shows that the worst charity donors expressed most regret: 42%, 33% and 11% for the 4th, 3rd and 2nd ranked charity, respectively. Furthermore, investigating the credibility of regret claims, Table 2 sheds light on how round 1 regret impacts search in round 2 for the treatment group. The variable ‘regret’ is a dummy equaling 1 if the subject displayed regret in round 1 for not donating to the top charity and 0 otherwise. The resulting coefficient shows that donors search more after receiving feedback if they also express regret in their donation decision from round 1.

3.2 Increased donor flow to the top charity

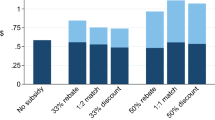

Figure 2 reflects the frequency distribution of supported charities, comparing control and treatment across rounds. While the number of subjects who get information on all four charities in round 1 differed significantly across groups, this did not translate into a significant difference in those donating to the top charity. Of those making a positive donation in round 1, 15% got information on the top charity in the control group and 22% in the treatment group. Of these, 67% donated to the top charity in the control group versus 55% in the treatment group, an insignificant difference. 77% (per group) of those who did not donate to the top charity despite getting information on it donated to the second-ranked charity suggesting that donors may care about other factors more than the provided measure.Footnote 15

Frequency distribution of charities donated to. The charities are represented by their rank (in order) on the x-axis. Includes observations with positive donation amount only. Despite searching, some chose not to donate, lowering the number of observations: round 1: 182 control, 183 treatment; round 2: 186 control, 184 treatment. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, using chi-square test

Although there is no difference in round 1 distributions across groups, round 2 distributions are significantly different (at p < 0.01, chi-square test): a lot more donations were made to the top charity in round 2 of the treatment group, unlike the control. While increased search in round 2 of the treatment group is the main driving force behind this result, about 13% of top-charity round 2 donors changed their decision in favor of the top charity in going from round 1 to 2.Footnote 16 A detailed analysis shows that 20 out of 42 subjects did not donate to the top charity despite getting information on it in round 1. Of those, 18 received information on the top charity in round 2, of which 13 donated to the top charity. This suggests that in the presence of feedback, donors not only search more but also make decisions that are indeed more aligned with third-party evaluations.

3.3 Donation levels remain unchanged

While most donors searched more among charities and donated to better ranked ones in the presence of feedback, an alternative way to avoid regret would be to not make any donations at all. However, the feedback neither improved nor hurt the donation levels: $42 on average for both rounds in the treatment. The control group’s donations averaged $40 and $38 in rounds 1 and 2 respectively; the difference being small and insignificant. The extensive margin of giving in the control was 82% and 84% in round 1 and 2, respectively, and that in the treatment was 85% in both rounds. Figure 3 further shows no difference across the two distributions for both rounds.

Looking for heterogeneity in giving, I investigate if donors substitute quantity with quality, that is donate less if donating to the top charity. For instance, those who donate to the top charity in round 1 of the treatment group may donate less in round 2: 37 subjects donated $51.76 on average to the top charity in round 1, with their donations dropping to $47.03 in round 2. However, this difference is not significant (p value equals 0.22 with paired t test, and 0.15 with Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Additionally, the mean donation amount of those donating to the top charity in round 2 (97 subjects) increased from $48 in round 1 to $49 round 2. Thus, providing feedback leaves the extensive margin and intensive margin of giving unchanged, directing money to better ranked charities, potentially improving the effectiveness of one’s donations.Footnote 17

4 Conclusion

This study employs an online experiment with real charities to investigate if absence of regret-inducing feedback on relative effectiveness of one’s donations is a contributing factor behind the lack of search among donors. Such feedback, which is absent in the real world, is made available exclusively to the treatment group over the course of 2 rounds. In response to anticipation of such feedback, individuals search relatively more and consequentially donate to better ranked charities. This increase in search is more pronounced in the second round for the treatment group, while there is no difference across rounds for the control group. When put in context with other related studies, these findings provide important insights into donor behavior: individuals are generally reluctant to seek information proactively, regardless of whether it comes at a cost (as observed in Null, 2011) or is provided freely (as in the control group of this study), unless they anticipate regret, as demonstrated in the treatment group. This suggests that the absence of regret-inducing feedback renders charity information less instrumental in donation decisions, thereby contributing to the prevalent lack of search among donors.

In conclusion, while there are ways to promote effective giving (Butera & Houser, 2017), the current study identifies an inherent feature in charities that prevent informed giving. Although the feedback provision feature of the experiment was useful in understanding what could be driving the lack of search among donors, it is not a recommended policy suggestion to promote informed giving: this sort of information provision is neither natural nor feasible in the real-world. However, knowing that donors are positively impacted by relative information on charity quality can be useful in designing policies and campaigns that can promote informed giving without hurting donations—a fruitful avenue for future research.

Data availability

Data available upon request.

Notes

Statistic from Money for Good Project by Hope Consulting, (2012).

National Center for Charitable Statistics document ∼1.5 million registered charities in the US. Charity Navigator lists ∼750 breast cancer charities with wide variation in impact.

Although Krasteva and Yildirim (2013) show that information can amplify warm glow.

Niehaus (2020) theoretically shows that charities’ credence nature allows for donor perception of their donation’s impact to diverge from its actual impact.

The information avoidance literature shows regret aversion induces people to avoid optional information (Golman et al., 2017). Contributing to this literature, this study investigates if one forgoes donating altogether in order to strategically avoid mandatory feedback, and thereby regret.

While this feature could artificially compel curious subjects to donate to see rankings, the donation data shows no evidence of this. In this design, subjects could donate just a penny to see the ranking, but the donation distribution (Fig. 3) of the treatment does not differ significantly from the control. Unconditional feedback, on the other hand, could artificially inflate search by encouraging subjects to find the top charity just to see if it matches the ranking, even if they don’t donate at all.

“For better or for worse, overhead ratio is the #1 piece of information donors are looking for.”.

One may argue for the presence of experimenter demand effect due to feedback. While this cannot be fully ruled out, the online nature of the survey ensured that no subject came in direct contact with the experimenter. It is unlikely that one would incur costs this large in terms of effort and time to satisfy the experimenter. Moreover, past experimental studies (Eckel et al. (2007), Karlan and Wood (2017)) that investigate provision of information find little to no effect, although a similar experimenter-demand effect may exist in their setting as well. One may also argue that the quiz-like design of the experiment may lead subjects to search more as people like to do well on quizzes in general. However, the presence of post-decisional feedback allows for regret to be experienced, driving people to exert more effort ex-ante and the quiz-like feature complements this mechanism. Lastly, a concern was raised regarding priming the subjects negatively with the regret elicitation question which could induce them to search more. The intention behind the question was to make regret salient. To mitigate the effects of priming, the wordings used in the options to the question purposely expressed regret or elation, allowing one to choose whichever option they most resonated with. Furthermore, if this had a negative priming effect, it is unclear it would only encourage subjects to search more as it could discourage donations altogether, negatively impacting search.

The second-ranked charities had missions related to food and water, making them a popular choice amongst the non-searchers as seen in the round 1 of both groups and round 2 of control. Perhaps subjects felt these factors were more important than the ranking.

These are the subjects who got information on top charity in round 1 but did not donate to it.

References

Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 14471458.

Bell, D. E. (1982). Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research, 30(5), 961–981.

Brown, A., Jonathan, M., & Williams, J. F. (2017). Social distance and quality ratings in charity choice. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 66, 9–15.

Butera, L., & Dan, H. (2017). Delegating altruism: Toward an understanding of agency in charitable giving. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 155(3), 99–109.

Butera, L., & Horn, J. (2020). “Give less but give smart”: Experimental evidence on the effects of public information about quality on giving. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 171, 59–76.

Coffman, L. (2016). Fundraising intermediaries inhibit quality-driven charitable donations. Economic Inquiry, 55, 409424.

Hope Consulting, “Money for Good: The US Market for Impact Investments and Charitable Gifts from Individual Donors and Investors,” Technical Report, Hope Consulting (2012).

Darby, M. R., & Edi, K. (1973). Free competition and the optimal amount of fraud. The Journal of Law and Economics, 16, 1.

Eckel, C., Grossman, P. J., & Milano, A. (2007). Is more information always better? An experimental study of charitable giving and Hurricane Katrina. Southern Economic Journal, 74(2), 388–411.

Exley, C. (2015). Excusing selfishness in charitable giving: The role of risk. The Review of Economic Studies, 83(2), 587–628.

Exley, C. (2020). Using charity performance metrics as an excuse not to give. Management Science, 66(2), 553–563.

Fethersonhaugh, D., Slovic, P., Johnson, S. M., & Friedrich, J. (1997). Insensitivity to the value of human life: A study of psychophysical numbing. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14(3), 283300.

Fong, C. M., & Oberholzer-Gee, F. (2011). Truth in giving: Experimental evidence on the welfare effects of informed giving to the poor. Journal of Public Economics, 95(5), 436–444.

Goette, L., & Tripodi, E. (2020). Does positive feedback of social impact motivate prosocial behavior? A field experiment with blood donors. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 175, 1–8.

Golman, R., Hagmann, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2017). Information avoidance. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(1), 96–135.

Jhunjhunwala, T. (2021). Searching to avoid regret: An experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 189, 298–319.

Karlan, D., & Wood, D. H. (2017). The effect of effectiveness: Donor response to aid effectiveness in a direct mail fundraising experiment. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 66, 1–8.

Krasteva, S., & Yildirim, H. (2011). (Un)Informed charitable giving. Journal of Public Economics, 106, 25.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1982). Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. Economic Journal, 92, 80524.

Niehaus, P. A theory of good intentions. Working Paper (2020).

Null, C. (2011). Warm glow, information, and inefficient charitable giving. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 455465.

Small, D. A., Loewenstein, G., & Slovic, P. (2007). Sympathy and callousness: The impact of deliberative thought on donations to identifiable and statistical victims. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(2), 14353.

Yoruk, B. Charity Ratings. University at Albany, SUNY, Department of Economics. http://ideas.repec.org/p/nya/albaec/13-05.html (2013).

Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 224–228.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Decision Sciences Collaborative and the Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Ohio State University (OSU). It was approved by the OSU IRB on 11/20/2015 (2015B0482). For helpful advice, I thank Lucas Coffman, John Kagel, Paul Healy, Mark Dean, Korie Amberger, Pedro Rey Biel, two anonymous reviewers, and various conference and seminar participants. Errors are my own.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

1.1 Online Instructions

1.1.1 Control

In this survey, you will be making decisions on how you would want to distribute the $80 between yourself and a charity that serves poor African communities. The charity names are altered to keep them anonymous.

For every 40 students who participate in this survey, one student's name will be drawn who will get the $80. If you get the $80, then the decisions you make in the survey regarding the distribution of the $80 will be implemented for you.

There are two rounds to the survey. Your decisions for only one of the two rounds will be implemented. Each round is equally likely to be selected for implementation.

The drawing for the $80 will happen on 4/30/2017, at noon. You will be provided with a donation receipt (if you make a donation) and the remaining balance from the $80 will be given to you. You will be notified via email if you win the drawing.

Note: Always click continue to move on to the next page.

1.1.2 Treatment

In this survey, you will be making decisions on how you would want to distribute the $80 between yourself and a charity that serves poor African communities. The charity names are altered to keep them anonymous.

For every 40 students who participate in this survey, one student's name will be drawn who will get the $80. If you get the $80, then the decisions you make in the survey regarding the distribution of the $80 will be implemented for you.

There are two rounds to the survey. Your decisions for only one of the two rounds will be implemented. Each round is equally likely to be selected for implementation.

If you donate to one of the four listed charities, their real names and their rankings based on their performance as evaluated by third-party organizations will be revealed to you at the end of EACH round.

The drawing for the $80 will happen on 4/30/2017, at noon. You will be provided with a donation receipt (if you make a donation) and the remaining balance from the $80 will be given to you. You will be notified via email if you win the drawing.

Note: Always click continue to move on to the next page.

1.2 Survey screenshots

1.2.1 Control

1.2.2 Treatment

All screens look the same as in the control group except the treatment group views an additional screen related to charity rankings (Fig. 8):

1.3 Procedure for ranking charities

In each round, there was only one top charity as determined by third-party charity evaluators such as GiveWell, Giving What We Can, and google.org: Against Malaria Foundation in round 1 and Give Directly in round 2. These 2 charities were the first-ranked charities. None of the other 6 charities were evaluated by a third-party evaluator as they evaluate only promising charities. Lunchbox Fund and Aqua Africa were ranked the second best because either they collaborated with other organizations/celebrities and/or because they provided their impact information in a quantitative nature. They also had high charity navigator ratings with an increasing donation trend over the years. The other four charities, that is the bottom 2 charities per round, were included in the study either due to missing impact information as its absence is likely to breed distrust or because of the qualitative nature of their self-reported impact information making it harder to judge its true value. Out of the bottom 2 charities per round, one of them was ranked fourth because it had spent more than 50% of the donation money on overhead (83% round 1 charity and 62% round 2 charity), along with a declining trend in donations. Coincidentally, a charity’s overhead expenditure was perfectly negatively correlated with its rank. Thus, while the top (first-ranked) charities were determined solely by third-party evaluations, a combination of factors such as external validation, amount spent on the cause (and not overheads), donation trend, charity navigator stars, and self-reported impact information were used to rank the non-top charities. Although the overhead costs were NOT (and should never be) the only criteria for ranking the charities in this study, it was one of the metrics provided for three main reasons: 1. Financials of the top charities revealed that they spent very little on overhead, 2. It made for a simple metric for subjects to understand, and 3. Donors value information on overhead costs according to donor reports (Hope Consulting, 2012). Ultimately, the ranking screen summarized three pieces of information per charity: percentage of donation spent on cause versus overheads, whether the charity was backed by third-party evaluator, and, if not, then whether the charity provided any impact information on its own. Most importantly, the subjects were not required to abide by these rankings in any way.

Appendix 2

2.1 Additional results

Figure 9 below provides summary statistics of all important variable across rounds and groups:

2.1.1 Donation levels conditional on search

To look further into the relationship between donation levels and search, the top panel in Fig. 10, graphs the mean donation level (with error bars) conditional on number of charities searched across control and treatment for both rounds. As can be seen, there is no significant difference between the two groups conditional on the number of charities searched. Besides a general trend of increasing donations with increasing search, in round 2 of the treatment one can see that the donation levels of individuals who searched 0 charities is significantly less than those who searched 2 charities.

Donation levels conditional on Search. Number of observations for each search level is stated in white inside the bar for the respective round and group. Excludes the 47 non-donors and the additional round-specific non-donors with control having 209 and 210 subjects in round 1 and 2 respectively and treatment having 207 and 206 subjects in round 1 and 2, respectively

The bottom panel of Fig. 10 divides these observations into 2 groups based on if an individual compared at least 2 charities before making a relatively more informed decision: ‘searched less than 2’ charities and ‘searched 2 or more’. Providing further evidence of the positive correlation between search and donation levels, we can see that the mean donation level increases with more search. Specifically for round 2 of treatment, those who compared charities, donated significantly more on average than those who did not.

2.1.2 Regret distribution across charities

Figure 11 below shows the distribution of reported regret in the treatment group over the 3 non-top charities. 146 subjects in total donated to a non-top charity in round 1 of the treatment group. Of them 79 donated to the 2nd ranked charity, 48 to the 3rd ranked and 19 to the 4th ranked. As shown in Fig. 11, 42% of those donating to the worst charity report experiencing maximum regret, followed by those donating to the third-ranked (33%) and then the second-ranked (13%) charities. This shows that donating to worse charities creates relatively more regret.

2.1.3 Impact of informed giving

Along with using the donation money to support a charity’s cause, charities use donation money to pay for overhead costs as well. While subtracting the money spent on overheads from total donations is a highly imprecise way to determine the true impact of donations, its numerical nature makes for an easy (to obtain and calculate) measure to get an estimate on the minimum impact created by one’s donation conditional on the charity donated to. Given the negative correlation between a charity’s rank and its overhead cost in the experiment, donating to a higher-ranked charity ensured a higher minimum impact of one’s donations in this setting. Thus, I use the proportion of donations spent on the cause (and not overhead) to get a handle on the minimum impact created by one’s donations depending on the charity donated to. I first average the percentage of donation amount spent on cause for similarly ranked charities across rounds for a fair comparison across rounds as the charities differed across rounds. Each donation made to a charity is then multiplied by this averaged percentage corresponding to that charity’s rank. The resulting variable, which is essentially the mean donation amount spent on cause represents the mean minimum impact created by donations depending on the charity donated to. As shown in Table 3 below, the average minimum impact derived is higher (but not significant) in the treatment group in round 1, with this difference becoming substantial and significant in round 2, as a result of donating to higher-ranked charities. This is true for the treatment group even when comparing across rounds. Thus, while mean donation levels across charities do not differ significantly, the charity to which the money is donated to can significantly affect the minimum impact generated by one’s donations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jhunjhunwala, T. Searching to avoid regret in charitable giving. J Econ Sci Assoc 9, 207–226 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-023-00138-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-023-00138-2