Abstract

We report results from a replication of Solnick (Econ Inq 39(2):189, 2001), which finds using an ultimatum game that, in relation to males, more is demanded from female proposers and less is offered to female responders. We conduct Solnick’s (2001) game using participants from a large US university and a large Chinese university. We find little evidence of gender differences across proposer and responder decisions in both locations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Solnick (2001), total amount to split was $10 with a $2 show-up bonus. The amounts paid in the US and China are equivalent in terms of purchasing power at University lunch providers, a relevant metric for most students.

In Solnick (2001), the actual first names of the subjects were used as their IDs in the Name treatment.

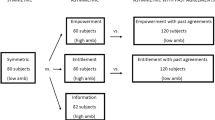

Solnick (2001) collected data on 65 pairs in the Name treatment (22 M–M pairs, 14 M–F pairs, 16 F–M pairs and 13 F–F pairs) and 24 pairs in the Number treatment (12 M–UN pairs and 12 F–UN pairs, or 14 UN–M pairs and 10 UN–F pairs).

We conduct the power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al. 2007).

Hao and Houser (2015) show that the WMW test is also appropriate for drawing inferences about location differences of binary data, such as comparison between frequency of favorable offers to male and female responders in main finding 1.2.

In order to compare easily across the US, Chinese and Solnick’s (2001) original data, we normalize all offers, MAOs and earnings to a maximum of 10. Specifically, we divide all offers, MAOs and earnings in the US sample by 2 and those in the Chinese sample by 4.

Unless noted otherwise, all p values refer to two-sided Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney (WMW) tests.

As in Solnick (2001), earnings refer to amounts earned out of the ultimatum game.

The 95% Confidence Intervals for males and females, calculated using the Mullin and Reiley (2006) method, overlap under each pairwise comparison. As a robustness check, we report p values using t tests based on standard errors clustered at the individual level for the recombinant sample following the approach described in Chen and Li (2009). Again, there are no significant differences.

References

Andreoni, J., Castillo, M., & Petrie, R. (2003). What do bargainers’ preferences look like? Experiments with a convex ultimatum game. American Economic Review, 93(3), 672–685.

Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 293–312.

Ayres, I., & Siegelman, P. (1995). Race and gender discrimination in bargaining for a new car. The American Economic Review, 85(3), 304–321.

Babcock, L., & Laschever, S. (2009). Women don’t ask: Negotiation and the gender divide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 789–865.

Castillo, M. E., & Cross, P. J. (2008). Of mice and men: Within gender variation in strategic behavior. Games and Economic Behavior, 64(2), 421–432.

Castillo, M., Petrie, R., Torero, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2013). Gender differences in bargaining outcomes: A field experiment on discrimination. Journal of Public Economics, 99, 35–48.

Chen, Y., & Li, S. X. (2009). Group identity and social preferences. American Economic Review, 99(1), 431–457.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic literature, 47(2), 448–474.

Dittrich, M., Knabe, A., & Leipold, K. (2014). Gender differences in experimental wage negotiations. Economic Inquiry, 52(2), 862–873.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2001). Chivalry and solidarity in ultimatum games. Economic Inquiry, 39(2), 171–188.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Gillen, B., Snowberg, E., & Yariv, L. (2018). Experimenting with measurement error: Techniques with applications to the Caltech cohort study. Journal of Political Economy. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/journals/jpe/forthcoming?mobileUi=0&.

Güth, W., & Kocher, M. G. (2014). More than 30 years of ultimatum bargaining experiments: Motives, variations, and a survey of the recent literature. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 108, 396–409.

Hao, L., & Houser, D. (2015). Adaptive procedures for the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test: Seven decades of advances. Communications in Statistics Theory and Methods, 44(9), 1939–1957.

Mullin, C. H., & Reiley, D. H. (2006). Recombinant estimation for normal-form games, with applications to auctions and bargaining. Games and Economic Behavior, 54(1), 159–182.

Saad, G., & Gill, T. (2001). Sex differences in the ultimatum game: An evolutionary psychology perspective. Journal of Bioeconomics, 3(2–3), 171–193.

Sandberg, S. (2013). Lean in: Women, work, and the will to lead. London: Random House.

Solnick, S. J. (2001). Gender differences in the ultimatum game. Economic Inquiry, 39(2), 189.

Sutter, M., Bosman, R., Kocher, M. G., & van Winden, F. (2009). Gender pairing and bargaining—Beware the same sex! Experimental Economics, 12(3), 318–331.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful comments from David Eil, César Martinelli, Johanna Mollerstrom, the editor Robert Slonim and two anonymous referees. We also would like to thank Biling Zhang, Xin Zhao and Yiqun Zhu for research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge research support from the Interdisciplinary Center for Economic Science at George Mason University and the Smith Experimental Economics Research Center at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. This research was funded by the Interdisciplinary Center for Economic Science at George Mason University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Qin, X. & Houser, D. Revisiting gender differences in ultimatum bargaining: experimental evidence from the US and China. J Econ Sci Assoc 4, 180–190 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-018-0054-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-018-0054-5