Abstract

Purpose

Despite a recent surge of interest in the role that self-identity plays in the process of desistance from crime, prior research has been mostly qualitative and conducted with small samples of adult offenders. In addition, while what people expect to become in the future can also function as motivational and sustaining forces toward prosocial behavioral outcomes, empirical tests of identity-based theories of criminal desistance have focused on the measures of current self-identity. We intend to address both gaps to expand the scope of desistance literature.

Methods

Drawing on 11-wave panel data of serious adolescent offenders, a modified version of negative binomial random-effects models is applied to estimate the within-individual effects of expectation of positive future selves on self-reported offending and official record of arrest.

Results

We found that a shift in a youth’s expectation of positive self-identity in the future is significantly related to a downward trend in both offending and arrest outcomes. This finding holds even after controlling for unobserved time-stable sources of heterogeneity and other important time-varying sources of potential confounders.

Conclusions

This study not only explores one of the understudied topics in the desistance literature but also provides evidence-based knowledge on which characteristics need to be addressed to initiate and maintain prosocial life styles among serious adolescent offenders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although self and identity have often been conceptualized differently across disciplines (see [11, 17, 52]; Owen, Robinson, and Smith-Lovin, 2010; [84]; Swann and Besson, 2010 for reviews), we use both concepts interchangeably hereafter because our primary goal is not to (re)define these concepts more systematically but to investigate the roles of self-identity change—as an important aspect of internal/subjective process—in the criminal desistance among juvenile offenders.

These models are equivalent to hierarchical linear models (HLM) when within-unit effect and between-unit effect are viewed as level 1 and level 2 effects, respectively.

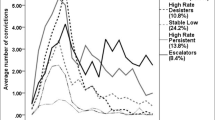

An anonymous reviewer suggested to interpret the results in Tables 2 and 3 in terms of a plausible level of within-individual change in the expectation of positive future selves based on the results from the unconditional growth curve model for positive future selves (which was estimated to increase by approximately 0.1 unit every year). However, the generalizability of the estimated overall growth rate becomes questionable when we cannot assume the existence of a unified and distinct functional form of individual trajectories [79]. Figure 1 clearly shows no commonality across individual trajectories, and thus the estimated fixed and random effects of growth parameters (e.g., intercept and slope) fail to properly summarize more complex nature of within-individual variations. Indeed, a more typical and realistic level of change appears to be a one-unit (or even more than one unit) change whenever it occurs.

Considering that these developmental changes within multiple domains of life occur simultaneously, which makes it hard to determine the temporal sequence of their complex interrelationships over time, these variables can also be conceived and tested as intervening variables that mediate the observed relationship between expected future selves and offending outcomes. We leave it up to future research.

Both mean and median of the between-individual level of expected selves were 3.62 and its standard deviation was 0.65. It ranged from 1.53 to 5 with middle 90% range of 2.57–4.68 and interquartile (middle 50%) range of 3.15–4.07.

References

Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 715–753.

Allison, P. D. (1998). Multiple regression: A primer. Thousand Oak: Pine Forge Press.

Allison, P. D. (2005). Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. Cary: The SAS Institute.

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Allison, P. D. (2012). Beware of software for fixed effects negative binomial regression. Downloadable at http://www.statisticalhorizons.com/fe-nbreg .

Allison, P. D., & Waterman, R. P. (2002). Fixed effects negative binomial regression models. In R. M. Stolzenberg (Ed.), Socological methodology 2002 (Vol. 32, pp. 247–265). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Antonaccio, O., & Tittle, C. R. (2008). Morality, self-control, and crime. Criminology, 46, 479–510.

Aresti, A., Eatough, V., & Brooks-Gordon, B. (2010). Doing time after time: an interpretive phenomenological analysis of reformed ex-prisoners’ experiences of self-change, identity and career opportunities. Psychology, Crime and Law, 16, 169–190.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Bachman, R., Kerrison, E., Paternoster, R., O’Connell, D., & Smith, L. (2016). Desistance for a long-term drug-involved sample of adult offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43, 164–186.

Baumeister, R. F. (1998). The self. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 680–740). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders. New York: Free Press.

Brame, R., Bushway, S. D., & Paternoster, R. (2003). Examining the prevalence of criminal desistance. Criminology, 41(2), 423–448.

Brown, J. (1998). The self. Boston: McGrawHill.

Burk, P. J. (2003). Relationship among multiple identities. In P. J. Burke, T. J. Owens, R. T. Serpe, & P. A. Thoits (Eds.), Advances in identity theory and research (pp. 195–214). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2011). Identity theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Callero, P. (2003). The sociology of the self. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 115–133.

Carver, C., & Scheier, M. (1990). Principles of self-regulation: Action and emotion. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Vol. 2. Foundations of social behavior (pp. 3–52). New York: Guilford Press.

Cauffman, E., & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of judgement in adolescence: why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 18, 741–760.

Cross, W. E., Jr., & Cross, T. B. (2007). The big picture: Theorizing self-concept structure and construal. In J. G. Draguns, W. J. Lonner, & J. E. Trimble (Eds.), Counseling across cultures (6th ed., pp. 73–88). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon (series Ed.) and N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (5th ed., Vol. III, pp. 1017–1095). New York: Wiley.

Erikson, E. H. (1946). Ego development and historical change. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 2, 359–396.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Identification as the basis for theory of motivation. American Psychological Review, 26, 14–21.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: Norton.

Falk, F. R., & Miller, N. B. (1998). The reflexive self: a sociological perspective. Roeper Review, 20, 150–153.

Farrall, S. (2005). On the existential aspects of desistance from crime. Symbolic Interaction, 28, 367–386.

Foote, N. N. (1951). Identification as the basis for a theory of motivation. American Sociological Review, 16, 14–21.

Frazier, L. D., Hooker, K., Johnson, P. M., & Kaus, C. R. (2000). Continuity and change in possible selves in later life: a 5-year longitudinal study. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 22, 237–243.

Furby, L., & Beyth-Marom, R. (1992). Risk-taking in adolescence: a decision-making perspective. Developmental Review, 12, 1–44.

Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich, S. A., & Rudolph, J. L. (2002). Gender, crime, and desistance: toward a theory of cognitive transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 990–1164.

Giordano, P. C., Schroeder, R. D., & Cernkovich, S. A. (2007). Emotions and crime over the life-course: a neo-median perspective on criminal continuity and change. American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1603–1661.

Gotfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gottfredson, M. R. (2006). The empirical status of control theory in criminology. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (pp. 77–100). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271.

Healy, D. (2013). Changing fate? Agency and the desistance process. Theoretical Criminology, 17, 557–574.

Healy, D. (2014). Becoming a desister: exploring the role of agency, coping and imagination in the construction of a new self. British Journal of Criminology, 54, 873–891.

Hirschi, T. (2004). Self-control and crime. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York: Guilford Press.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. R. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89, 552–584.

Hsiao, C. (2003). Analysis of panel data. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Huizinga, D., Esbensen, F., & Weiher, A. W. (1991). Are there multiple paths to delinquency? Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 83–118.

Iselin, A. R., Mulvey, E. P., Loughran, T. A., Chung, H. L., & Schubert, C. A. (2012). A longitudinal examination of serious adolescent offenders’ perceptions of chances for success and engagement in behaviors accomplishing goals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 40, 237–249.

Kerrison, E. M., Bachman, R., & Paternoster, R. (2016). The effects of age at prison release on women’s desistance trajectories: a mixed-method analysis. Journal of Developmental and Life Course Criminology, 2, 341–370.

Kinch, J. W. (1963). A formalized theory of the self-concept. American Journal of Sociology, 68, 481–486.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2001). Understanding desistance from crime. Crime and Justice, 28, 1–69.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

LeBel, T. P., Burnett, R., Maruna, S., & Bushway, S. (2008). The “chicken and egg” of subjective and social factors in desistance from crime. European Journal of Criminology, 5, A131–A159.

Lemer, R. M. (1978). Nature, nurture, and dynamic interactionism. Human Development, 21, 1–20.

Lemert, E. (1951). Social pathology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Markus, H. R., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954–969.

Markus, H. R., & Wurf, E. (1987). The dynamic self-concept: a social psychological perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 38(1), 299–337.

Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: How ex-convicts reform and build their lives. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association Books.

Massoglia, M., & Uggen, C. (2007). Subjective desistance and the transition to adulthood. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(1), 90–103.

Matsueda, R. L. (1992). Reflected appraisals, parental labeling, and delinquency: specifying a symbolic interactionist theory. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 1577–1611.

Matsueda, R. L., & Heimer, K. (1997). A symbolic interactionist theory of role-transitions, role-commitment, and delinquency. In T. P. Thornberry (Ed.), Developmental theories of crime and delinquency (pp. 163–213). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self & society. The University of Chicago Press.

Menard, S., & Elliott, D. S. (1996). Prediction of adult success using stepwise logistic regression analysis. A report prepared for the MacArthur Foundation by the MacArthur Chicago–Denver Neighborhood Project.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

Na, C., Paternoster, R., & Bachman, R. (2015). Within-individual change in arrests in a sample of serious offenders: the role of identity. Journal of Developmental and Life Course Criminology, 1, 385–410.

Opsal, T. (2012). “Livin’ on the straights”: identity, desistance, and work among women post-incarceration. Sociological Inquiry, 82, 378–403.

Osgood, W. D., Wilson, J. K., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review, 61, 635–655.

Overton, W. F. (1990). Reasoning, necessity, and logic: Developmental perspectives. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Oyserman, D. (2007). Social identity and self-regulation. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 432–453). New York: Guilford Press.

Oyserman, D. (2009). Identity-based motivation: implications for action-readiness, procedural readiness, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19, 250–260.

Oyserman, D. (2015). Pathways to success through identity-based motivation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Oyserman, D., & Destin, M. (2010). Identity-based motivation: implications for intervention. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(7), 1001–1043.

Oyserman, D., & James, L. (2011). Possible identities. In S. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 117–148). Springer-Verlag.

Oyserman, D., & Markus, H. R. (1990). Possible selves and delinquency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(1), 112–125.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72.

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., Terry, K., & Hart-Johnson, T. (2004). Possible selves as roadmaps. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 130–149.

Oyserman, D., Elmore, K., & Smith, G. (2012). Self, self-concept and identity. In M. Leary & J. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 69–104). New York: Guilford Press.

Oyserman, D., Lewis, N. A., Jr., Yan, V. X., Fisher, O., O’Donnell, S. C., & Horowitz, E. (2017). An identity-based motivation framework for self-regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 28(2–3), 139–147.

Paternoster, R., & Bushway, S. (2009). Desistance and the feared self: toward an identity theory of desistance. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 99, 1103–1156.

Paternoster, R., & Pogarsky, G. (2009). Rational choice, agency, and thoughtfully reflective decision making: The short and long term consequences of making good choices. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 103–127.

Paternoster, R., Pogarsky, G., & Zimmerman, G. (2011). Thoughtfully reflective decision-making and the accumulation of capital: bringing choice back in. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 27, 1–26.

Paternoster, R., Bachman, R., Kerrison, E., O’Connell, D., & Smith, L. (2016). Human agency and desistance from crime: arguments for a rational choice theory and an empirical test with survival time. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43, 1204–1224.

Radcliffe, P., & Hunter, G. (2016). ‘It was a safe place for me to be’: accounts of attending women’s community services and moving beyond the offender identity. British Journal of Criminology, 56, 976–994.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Rocque, M. (2015). The lost concept: the (re)emerging link between maturation and desistance from crime. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 15(3), 340–360.

Rocque, M. (2017). Desistance from crime: New advances in theory and research. Palgrave Macmillan US.

Rocque, M., Posick, C., & Paternoster, R. (2016). Identities through time: an exploration of identity change as a cause of desistance. Justice Quarterly, 33, 45–72.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sedikides, C., & Brewer, M. B. (2001). Individual self, relational self, collective self. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Silver, E., & Ulmer, J. T. (2012). Future selves and self-control motivation. Deviant Behavior, 33, 699–714.

Skardhama, T., & Savolainen, J. (2014). Changes in criminal offending around the time of job entry: a study of employment and desistance. Criminology, 52, 263–291.

Soyer, M. (2014). The imagination of desistance: a juxtaposition of the construction of incarceration as a turning point and the reality of recidivism. British Journal of Criminology, 54, 91–108.

Steinberg, L., & Cauffman, E. (1996). Maturity of judgment in adolescence: psychosocial factors in adolescent decision-making. Law and Human Behavior, 20, 249–272.

Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Monahan, K. (2015). Psychosocial maturity and desistance from crime in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, March, 1–12.

Stevens, A. (2012). I am the person now I was always meant to be: identity reconstruction and narrative reframing in therapeutic community prisons. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 12, 527–547.

Stone, R. (2016). Desistance and identity repair: redemption narratives as resistance to stigma. British Journal of Criminology, 56, 956–975.

Sweeten, G. (2012). Scaling criminal offending. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28, 533–557.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2000). The self-report method for measuring delinquency and crime. Criminal Justice., 4(1), 33–83.

Vaughan, B. (2007). The internal narrative of desistance. British Journal of Criminology, 47, 390–404.

Vera, E. M., & Reese, L. E. (2000). Preventive interventions with school-age youth. In S. Brown & R. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (pp. 411–434). New York: John Wiley.

Warr, M. (1998). Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology, 36, 183–216.

Wikström, P. H., & Treiber, K. (2007). The role of self-control in crime causation: beyond Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. European Journal of Criminology, 4(2), 237–264.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Na, C., Jang, S.J. Positive Expected Selves and Desistance among Serious Adolescent Offenders. J Dev Life Course Criminology 5, 310–334 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-019-00109-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-019-00109-4