Abstract

Purpose

This article emphasizes the complexity of desistance processes by exploring how echoes of violent victimization from intimate partners work as a hindrance or barrier to desistance. Drawing on interviews with women who are striving to desist, this article seeks to elucidate how past experiences of excessive and recurring violent victimization affect the life course, with a focus on their restrictions on the women’s desistance processes.

Methods

This paper is built upon repeated qualitative interviews with ten women in the early stages of their desistance processes. They were all interviewed repeatedly on a 6-monthly basis for 2 years. Echoes of violent victimization as a hindrance to desistance emerged as a theme during the interviews and are explored further via a thematic analysis.

Results

Echoes of violent victimization from intimate partners restrict the women’s social lives, complicating an already fragile (re)connection to conventional society. Additionally, many of the women are restricted by post-traumatic stress disorders directly related to their violent victimization, which impedes their agency and limits their abilities to act towards desistance.

Conclusions

Recurring violent victimization has severe implications for the women’s desistance processes. Both social and health-related consequences of this violence restrict the women’s ability to act towards desistance from crime and expose them to painful experiences of isolation, goal failure, and hopelessness. These conclusions are important contributions to the understanding of the complexity of desistance processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The study of pathways out of crime has traditionally focused on mechanisms that facilitate (men’s) desistance. This body of research highlights how certain events, such as getting married, obtaining employment, or stable housing, can present turning points in a criminal lifestyle. Such events offer changes in social control, routine activities, and the individual willingness to change conceptualized as agency [5, 20, 27, 38, 53, 55, 57].

However, as Matza put the matter as early as 1969: “being willing is not quite the same as being able” ([46], p. 112, emphasis added). While desistance can be quite straightforward and unproblematic for some people, for others there is far more to the process than a simple matter of choice [18, 24]. Individuals with the will to desist who make continuous and agentic efforts to succeed can find themselves obstructed by structural factors such as a lack of social, material, or financial resources needed to be able to change their lives and desist [18, 24, 51]. In recent years, desistance research has broadened to include factors obstructing or constraining ongoing desistance processes (see, e.g., [17, 52]).

Interestingly, such obstructing factors can overlap with the aforementioned facilitating factors. Much life-course research has been conducted regarding the importance of a romantic partner for (men’s) desistance from crime (see, e.g., [39]). For women, victimization by intimate partners has been linked to pathways into crime [11]. Research has also shown how women with histories of abusive relationships often offend directly or indirectly because of these relationships [40]. However, it is still unclear how intimate partner violence may affect desistance from crime (although see [12]). This article aims to elucidate this matter.

Drawing on repeated and qualitative interviews with ten women who are striving to desist from criminal lifestyles, this article will focus on the women’s experiences of exposure to violent victimization from intimate partners, and how such experiences have long-term effects on the women’s life courses. More specifically, the focus of this contribution will be on how echoes of violent victimization restrict the women’s attempts to desist from crime. The term “echoes” emphasizes how past traumas reverberate off of the barriers that the women are facing when attempting desistance. As an echo from the past distorts every time it bounces, lingering experiences of past violent victimization evoke new experiences of hindrances to the women’s desistance processes, long after the violent relationships are over.

Women’s Violent Victimization

Violence against women affects the lives of women worldwide at every age, of every class, religion, and ability [69]. Violent victimization is especially common among disadvantaged groups, such as homeless people, drug users, and those with convictions [33, 50]. Such disadvantages are common among women involved in criminal lifestyles, and research indicates that this group of women is especially susceptible to violent victimization [22, 28, 31, 32, 35, 36, 43, 56, 59, 62].

Violence against women comprises many different forms, including physical, psychological, and sexual violence both where the perpetrator is an intimate partner, and where there is no such relation between the woman and her perpetrator [19]. By definition, physical violence and sexual assault also involve psychological abuse [28]. Exposure to such violence is associated with a long range of negative health effects, such as post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), fear and anxiety, depressive symptoms, and functional impairments as well as low self-esteem and low life satisfaction [3, 30, 41, 68].

Criminological research on the effects of being exposed to violence has typically studied short-term consequences such as fear of (further) victimization, along with adaptations to such fear. From a slightly different point of view, clinical psychological research typically focuses on the link between violent victimization (primarily in childhood) and the long-term effects on the victim’s psychological well-being [42, 68]. There is a gap in the research considering the social implications of exposure to violent victimization and how it affects the life courses of victims [42]. Longitudinal and life-course research on how exposure to violent victimization affects the life course from a more sociological point of view would be useful to explore the social implications of such violence. This article aims to contribute to the filling of this research gap by making a sociological contribution to the understanding of the effects of recurring violent victimization on the life course. Specifically, the article will explore how echoes of intimate partner violence restrict the studied women’s attempts to desist from crime.

Violence Against Women in Criminal Lifestyles

Research on women involved in criminal lifestyles paints a world of ubiquitous violence [22, 31, 32, 35, 36, 43, 56, 59, 62]. Women active in criminal lifestyles (which often include drug (ab)use) are subjected to continuous violence on a level that is difficult to comprehend for someone who is not familiar with a criminal lifestyle or the narcotic drug scene ([28, 31]; see also [49]). Criminally active women’s exposure to violence can be described as multidimensional. While violence against women generally takes place within the home environment, women in criminal lifestyles are victimized both at home and in public spaces and by many different categories of people, including male partners, other men and women in the street crime setting, and also police officers and security guards. Studies show that the risk for a drug (ab)using woman also being a victim of violence is considerably higher than the chance of her not being victimized [28, 66]. Previous research also highlight that women in criminal lifestyles (often involving drug (ab)use) are more likely to partner with criminally active men who are more prone to being abusive [28]. This can be linked to gender norms and heteronormativity, as Messerschmidt [48] has shown how criminal activities can be a successful way of doing masculinity, while the same actions could be detrimental to a female gender project (see also [8]). In other words, criminally active men can pass as attractive, while criminally active women are publically punished as fallen (see also [10]). Holmberg et al.’s [28] interviews with women drug users in Sweden show that many of them have experiences of at least one, but oftentimes several, violent relationships with criminally involved and drug abusing men where physical violence is common. Many of the interviewed women seemed to perceive violent victimization as an unavoidable part of relationships within the street crime setting. Physical violence and sexual assault are common features of such relationships, along with control and isolation as well as financial abuse [22, 28]. Women are often cut off from their contacts with friends and relatives while living in abusive relationships. Having been controlled and abused by an intimate partner can also undermine the victim’s perception of agency and self-efficacy, along with her perceptions of and beliefs about other members of (conventional) society [22, 42]. Since agency is understood as key to any desistance process (see, e.g., [15]), having the perception of one’s own agency undermined could imply barriers to any efforts to change one’s life and desist from crime. If the perception of other members of society is changed from being sources of support to becoming sources of harm or threat, that could entail severe limitations to an individual’s ability (and desire) to (re)establish prosocial contacts and connect with conventional society. As such, the controlling elements of intimate partner violence can result in long-term consequences, impeding victims’ desistance processes.

Women active in criminal lifestyles are often reliant on their perpetrators, i.e., by being dependent on a partner to get drugs or money for drugs. They also rarely have stable accommodation of their own, and therefore have nowhere to go to get away from violent partners. Lastly, criminalization comes with a master status and a stigma that makes criminally active women reluctant to seek aid when victimized, as they fear that the response would be control, rather than support ([22, 28]; see, e.g., [58]). Due to this, criminally active women exposed to violence typically only contact hospitals and authorities in an emergency [22, 28]. Contacting authorities while in a drug (ab)using and criminal lifestyle can also lead to other repercussions such as a risk of losing care of children ([28]; see also [60]). This is likely to be especially true in Sweden (where the present study was conducted) since Sweden has a history of punitive social policy on drug use, and even the personal intake of illicit drugs is criminalized [21].

If the authorities are informed about intimate partner violence against a woman, interventions are focused on convincing her to leave her perpetrator [28]. However, leaving a violent relationship does not guarantee that the victimization will end. Research shows that a violent situation can escalate into a life-threatening one once a woman attempts to leave her abuser [7, 13, 26]. In interviews, women report how they were pursued for a long time after the separation [14]. This is especially true when the violent partner is also involved in a criminal lifestyle as such men are often used to acting violently outside of the home environment. Men in criminal lifestyles can also have extensive networks that allow them to pursue and find women that are trying to hide from them. On the other hand, criminally active women living in a violent relationship are oftentimes stripped of their support networks as part of the control and isolation executed by their perpetrators. This lack of a social network makes it harder to get away from a violent relationship [13, 22, 28]. Indeed, fear of complete isolation has been highlighted by previous research as a cause for women not leaving violent relationships [28].

Long-Term Consequences of Violent Victimization

Even if repeated and violent victimization did end as the woman escaped from her perpetrator, the experiences of violence may have long-term effects that linger and affect the woman long after the relationship is over. Most research on the long-term effects of violent victimization is clinical and focused on psychological health effects ([42]; see also [3, 9, 63, 65, 67]). Within this body of research, developmental and life-course studies are often focused on violent victimization during childhood and its consequences through life, thus differing somewhat from this present article’s focus on adult women’s experiences and consequences through life (see, e.g., [4, 30, 42]). A review of this literature clearly shows that violent victimization has a negative impact on the victim’s psychological well-being over the life course [42]. Research shows increased prevalence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among victims of violence. These psychological effects are especially apparent among women who have experienced abuse by multiple partners [2]. When interviewing 391 adult women, Kilpatrick et al. [34] found that more than a quarter of those who had ever been victimized (by any crime) subsequently developed PTSD. Alcohol and drug dependencies are also among the outcomes of previous violent victimization [6, 42]. Drugs are sometimes used as self-medication to treat the harmful effects of both the violence and the subsequent PTSD [36, 65]. The link between violent victimization and long-term psychological consequences is thus well documented. Despite this, the social implication of such victimization on the life course is still understudied [3, 42].

Possible Implications of Violent Victimization on Desistance From Crime

The meaning of the term “desistance” is widely debated [24, 55]. Within this paper, desistance from crime is conceptualized as complex processes involving a major change in lifestyle, aimed at moving from “deviance” to “conventionality” (see [18] for a similar approach to desistance).

In recent years, research developing the understanding of desistance has taken on the task of exploring the mechanisms obstructing or constraining an ongoing desistance process. Such obstructions to desistance processes have been conceptualized as structural barriers to opportunities to exercise one’s individual capacities [17, 47, 64].

Nugent and Schinkel [52] offer an important contribution to the matter of barriers to desistance. Theorizing the pains of desistance, the authors divide the desistance process into three spheres: act desistance referring to non-offending, identity desistance referring to the internalization of a non-offending identity, and relational desistance referring to a recognition of change by others [52]. As such, they make it quite clear that part of the complex desistance process lies beyond the actions of the individual herself, involving the acceptance and recognition of desistance by other people [64]. Nugent and Schinkel [52] further distinguish between three pains involved in the maintenance of desistance: the pains of isolation, goal failure, and hopelessness. In order to maintain act desistance, individuals tend to knife off their old friends, meaning that they cut off contact to peers that could potentially pull them back towards a criminal lifestyle (see also [38, 45]). An inability to connect to prosocial networks or new activities led most of the studied group to experience the pain of isolation. Not only does this lead to loneliness, but it could also lead to an indecisive perception of self as the people in Nugent and Schinkel’s [52] study previously had identified strongly with the gangs that they had been involved with. The desisters found themselves stuck in a liminal position: they neither identified with their old offending selves nor with a new identity as changed and accepted part of conventional society (see also [29]). A clash between the need to achieve identity desistance, while not obtaining the recognition of this needed for relational desistance (most notably manifested in an inability to obtain employment), led to the pain of goal failure. A combination of the pains of isolation and goal failure led to the further pain of hopelessness. A lack of hope made life less fulfilling and sustained desistance less probable [52].

As shown by previous research, isolation is a common feature of intimate partner violence. Research has also shown that the stigma of being perceived as a convicted woman may lead to isolation due to shame [28, 58, 60, 65]. This, in combination with the strong link between violent victimization and mental illnesses such as PTSD, could make it harder for a willing desister to (re)establish contact with conventional society. As such, desisters who are survivors of intimate partner violence might be more prone to goal failure and hopelessness as well. Thus, drawing on lessons from research on the long-term effects of violent victimization by intimate partners, such victimization could work as a hindrance to survivors’ desistance processes as it may actualize all three of the pains of desistance as suggested by Nugent and Schinkel [52]. This paper will investigate this potential in order to develop the understanding of desistance processes.

Method

This paper is based on findings from a field study, which followed the desistance processes of ten women. The criterion for inclusion in the study was that the women identified themselves as currently striving towards a changed lifestyle, leaving criminality behind them. As such, all of the women were occupied with efforts to desist from crime, and all of the women were in early stages of desistance when I first met them. Early stages is used in this study to emphasize the processual aspect of desistance, and refers to the initial phase of any desistance process. As such, it is not linked to age, but to time spent on a desistance journey (see [16] for a similar approach). I contacted the women through gatekeepers in different spheres all involved with women’s (and men’s) reentry into society. The gatekeepers were probation officers, prison staff, and staff at different nongovernmental organizations that facilitate reentry. I also had adverts inside several probation centers as well as inside of prisons in different parts of Sweden.Footnote 1 I recruited the ten women from all of those different areas. This broad approach was strategic as I thought that experiences of desistance might vary depending on whether or not a woman was supported by NGO’s or probation centers.

Using a prospective and longitudinal design, the women were interviewed repeatedly on a 6-monthly basis for a total of four interviews per woman. This setup is theoretically relevant, as it allowed me to interview the women frequently during an intensive period of their desistance processes. Hence, I was able to get close and take part in their desistance processes as they unfolded. This is a strength as it differs from many of the studies that have had most influence on desistance theory (see, e.g., [38]; cf. [18]). The first sweep of interviews had a more traditional and retrospective life-history style, where we talked about where they were in life, what they had experienced in the past, and also looked forward towards what the women thought and hoped was to come. The three sweeps of follow-up interviews were focused on the women’s everyday lives striving towards desistance from crime, and what they did and felt at the time of our meetings. However, following up on threads and themes from our previous sessions meant that the follow-up interviews also contained both retrospective and prospective reflections. The usual interview lasted between two and two-and-a-half hours, but shorter as well as longer interviews did occur. Meeting the women repeatedly for such long interviews provided a richness and depth to my understanding of the women’s different situations in striving towards desistance. The interviews were conducted in the women’s homes, their workplaces, in parks, in prisons, in my office at Stockholm University, and in meeting rooms at the NGOs. The women always picked the location themselves, and quite often I was able to meet them in an environment where they normally spent their time, thus adding an ethnographic element to my research. Each interview was set up over the phone, and sometimes these phone calls became lengthy and touched on themes that are relevant for the project. With permission from the women, some phone calls were recorded and transcribed as part of the research material.

The Women

The ten women are of different ages, spanning from 23 to 53 at the first interview (some basic characteristics of the women are shown in Table 1). They live in different parts of Sweden and are of Swedish or other Scandinavian ethnicity. Seven of the ten women have children. The women all have different experiences of what a criminal lifestyle may entail. Every one of them has spent decades in such lifestyles. This includes the youngest in the sample, Norah, who begun her habitual drug intake at age 11. All but one (Nina) have been using and/or abusing illicit narcotic drugs on a regular basis. While intake of narcotic drugs is a crime in Sweden, the women have also engaged in common street crime such as drug dealing, assault, robbery, theft, and burglary, and their lives revolved around these activities pre desistance. Although all women had been convicted in the past, their incarceration histories varied significantly. While one woman had never been incarcerated (Maia), all of the other women had been incarcerated on multiple occasions, and the longest aggregated conviction history was Johanna’s, who had spent a total of 13 years in prison.

Method of Analysis

The interviews were transcribed and then analyzed thematically. The project has a broad approach, striving to improve the understanding of women’s desistance. As such, the initial interview included many themes such as family, peer and partner relations, experiences of police, prison and social services, drug use, and other criminal activities as well as resource-focused themes such as financial situation, debts, education, employment, and health. Another theme was victimization, and the specific theme in focus for this paper is the women’s experiences of intimate partner violence and how it affects and restricts their desistance processes. This theme manifested itself at the first sweep of interviews, and grew with every follow-up. Already in the first round of interviews, I discovered that all of the women had experiences of recurring violent victimization, primarily from intimate partners. Although these violent relationships were now ended for all of the women when I met them, the effects of such trauma were striking in their narratives. One of the women lived with a protected identity due to previous intimate partner violence when I met her, and it was clear that this affected her greatly. Obtaining a protected identity entails a variety of life changes, including acquiring a new name, moving, and keeping the new address from official registers.Footnote 2 Other women talked about how such protected identities had affected them in the past, but also how they still were affecting them, even though those women were not living with protected identities any more. This was my entry point into what would later present itself as a manifold myriad of ways that previous violent victimization was still affecting the women’s agentic efforts to change their lives and desist from crime. While coding the interviews into different themes, it became increasingly apparent how big an overlap there was between the three nodes Victimization, Partners, and Health. As such, the thematic analysis was continuing and took place during the interviews as well as within the transcription and coding procedures. Quotes from the transcriptions are presented to support the analysis. Here, all names are pseudonyms. Words in (brackets) are used to anonymize certain details such as places, people, or work titles. A slash, /, is used to indicate interrupted sentences. Finally, the analysis use both past and present tense, to point out how past experiences echoes back to amplify barriers in the present.

Recurring Violent Victimization

While living in criminal lifestyles, all of the women were victimized by violent men, and all of them have lived with a violent intimate partner during a period of their lives. Therefore, this result presentation and analysis begins with painting a picture of the violence that the women have endured.

The interviews with the women are full of vivid examples of violent victimization. Phrases such as “It [violence] is so damn common in that setting, you know” exemplifies the ubiquity of violence within the setting of criminally active women’s daily lives. When asked “What has victimization been like to you?,” Marie responded:

Marie: I’ve actually done well, all things considered. Sure, I’ve met some cruel guys who’d hit me and stuff. But I’m one of very few girls who haven’t been raped, you know.

The victimization included both intimate and non-partner violence, as well as sexual, physical, and psychological abuse and can thus be described as multidimensional (as suggested by [28]). However, when focusing on the life-course implications of violent victimization, the violence done by intimate partners clearly stands out in the women’s narratives. It is worthy of note that the women’s framing of their violent histories did not seem to change over time in the interviews. This is theoretically interesting, as intimate partners have been highlighted by previous research as facilitators of desistance for men (see, e.g., [39]) and as criminogenic for women (see, e.g., [40]), while the impact of intimate partner violence on desistance still is in need of exploration. Therefore, my analysis will focus on the women’s experiences of intimate partner violence.

All of the women have been exposed to violence by intimate partners. The interviews clearly show how common such violence is, and also how the women seem to expect to be victimized by intimate partners and thus normalize violent victimization and perceive it as an unavoidable part of relationships within a drug active street setting (cf. [22, 28]). A partner injected Marie with narcotic drugs different from the ones she normally used, tied her to the bed, and left her there in a “critically psychotic state” to lie in her own vomits and without water for 3 days before he threw her over the balcony and she landed in the snow. Despite this, her response to my question about victimization was that she had “done well,” as she had not been raped. This is a telling example of how violent victimization is normalized within a drug abusing lifestyle. Other quotes also offer insights on the prevalence and severity of violence for women in the scene, as is present in an example from Johanna. When I asked her about her previous victimization, she told me:

Johanna: Well I do have my boyfriends then who have/many of them... well basically all of them… except for one though. […] Other than him, of course I’ve been assaulted, you know [R: Yeah]. Like my youngest son’s dad, he’s dead now, he’d snap my arms and ribs off to hell and back.

For one and a half years, Sofia was in a relationship with a man she describes as “extremely violent.” He repeatedly kept her locked up in their house for days, physically abusing her. She described the first time this happened:

Sofia: The first time it happened, I don’t think it took more than three months. And he just smashed me to pieces. [R: Yeah?]. He kept me locked up for three days. He punched me and he kicked me half to death. There was a baseball bat and everything, I mean, you know…

Beside the physical violence, Sofia’s experience of intimate partner violence is also full of psychological trauma, not least from being repeatedly locked up for weeks at a time. She managed to escape on a number of occasions, seeking refuge at her sister’s or her best friend’s. Her perpetrator always found her, often by pursuing, visiting, and threatening those friends and relatives. Sofia also had a beloved pet at the time, and whenever she managed to escape without her pet, her abuser used the pet “as hostage,” forcing her to come back. It is evident that the women themselves are not the only victims of the intimate partner violence, but friends, relatives, children, and pets are also affected. Johanna told me of how her son (Nick) was part of her own victimization:

R: Was he mean to Nick too?

Johanna: Once I think he got a/I had gone to bed like, when he was really little [she shows me how she lies with her son in her arms, cheek to cheek]. When he burst in and gave me the worst blow! I don’t know, but I think that Nick/ [she shows me the blow, a swinging fist to her head, and how the fist might have also hit their son in the swing, also in the head, after it had hit her].

R: Yes.

Johanna: But then I was like “oh no, I forgot to buy formula, I need to go buy formula,” you know. And like, “Oh shit, I’ll bring Nick.” And Nick knew exactly what was going on, and he saw me sneak off to pack his things.

R: Yeah.

Johanna: And he had a toy box, and a yellow tractor. One of those plastic tractors that I’d bought the last time we were/we’d gone off […] Yeah, and he sneaks off to fetch that tractor and then we packed it in the bag together. [R: Right… yeah...] So of course he’s also been/ [...] Yeah, and he has seen too much you know.

Most of the women have children, and it is evident in the women’s narratives that the victimization of their children had a great impact on the trauma that they still suffered many years later. Maia, whose daughter always lived with her growing up and therefore experienced all five of Maia’s abusive relationships first hand, exemplifies this. When talking about the relationship with her daughter in our interviews, Maia is full of anguish and remorse. At our first interview she told me how “It is a very sensitive topic we’re getting into now […] There’s a lot of guilt and shame.” Later on in that interview when talking about her current contact with her last ex-partner (who was not violent towards her), she broke down in tears as she said:

Maia: Every time I tell this… it is so damn hard! [R: Yes]. And I don’t know if I’ll ever get rid of this. I don’t know if I can be whole again. I don’t want to hurt anyone! [sobbing] Least of all my daughter! [R: Yes, of course!] I mean, I know I couldn’t harm her in any way. But I’m sure I still have. When she depended on me. When she was a child.

Touching upon the subject of self-efficacy again in interview four, Maia told me that her feelings of guilt and shame were both internally induced because of how she felt that she had failed as a mother, but also how her abusive intimate partners have forced this self-image on her. She told me that when she is feeling down, she tends to relive insults and hurtful words that others have said to her and which reminds her of her feelings of being a bad mother.

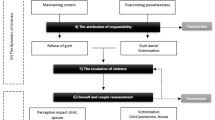

Echoes of Violent Victimization

In the long run, violent victimization has both social and health-related consequences for the women. Although the violent experiences highlighted above are behind them, their consequences still reverberate and constrain the women’s ongoing desistance processes by making barriers commonly found among desisters even harder to overcome (see, e.g., [52]). Below, the results and ensuing analytic discussion are divided into the aforementioned themes, social and health-related consequences of violent victimization.

Social Consequences

During the one and a half years that Sofia was in a relationship with the extremely violent man, she was severely restricted in her social relations. The only family she has left alive is her older sister, but as she tells me: “We lost touch for over a year. When I didn’t have contact with anyone… when I was with (the violent perpetrator).” This is a telling example of how the controlling mechanisms of intimate partner violence result in a state of isolation for the women (cf. [22, 42]).

When she finally escaped him, Sofia was placed at a women’s shelter for victims of violence. The abuser pursued her incessantly, and found her due to a breach in security. Sofia was then quickly moved to another part of the country. She stayed at this new shelter for 10 months, changed her name, and obtained a protected identity. Some time after she was transferred, she reported the violence to the police, and the perpetrator was sentenced to several years in prison. She broke away from the abusive man a few years ago, and was living with a protected identity at the time of interviews. When reflecting on her present situation, she said:

Sofia: I refuse to be restricted... I mean of course I’m fucking restricted with the protected identity and everything. I mean I’m not allowed to go to (the old hometown), not allowed to/I mean all of those things. Can’t ever appear on a photo that could risk getting out on the internet. All that stuff. [R: No, no]. So sure, I am restricted. But I’ll have to live with that. That’s how it is.

Furthermore, during our interviews, it became obvious that the violence she experienced has had a severe impact on her social life. She now feels restricted both in her contact with her sister (the only family she has left alive) and in her ability to socialize and meet new people. However, having been stripped of her former support network, meeting new people is required to break the isolation that otherwise risk to become an impeding pain to her desistance process, as suggested by Nugent and Schinkel [52]. She elaborated on how the past violence has put a strain on her relationship with her sister. Before actually getting away from the abusive man, she made several attempts at escaping. During one such attempt, she locked herself up at her sister’s, who helped her. But “Then (the man) went to see her and threatened her and stuff, but... [sighs] and then she said ‘I have my own family and my kids and everything’ you know. ‘Of course!’ I told her, ‘I’m not gonna argue with that!’.” During her time with the abuser, she had no contact with her sister, or anyone else for that matter. Later, her sister was a witness in the trial against her perpetrator. Currently, Sofia and her sister speak regularly on the phone. For now, that is all they can do, as the protected identity restricts Sofia from visiting her old hometown. This is a clear example of how echoes of past violent victimization reverberate off of the barrier of isolation which is a common obstruction to desistance processes (see [52]), making an already tough obstacle even harder to overcome.

Three of the women in this study have lived with protected identities because of the violence they had experienced. While the protected identity was helpful or even necessary in order to survive the extreme and escalating violence that their partners exposed them to, it also comes with a price. All of these women bear witness to similar hardships as outlined by Sofia above. The protected identity forces the women to move from their old hometowns and knife off their bonds to friends and even relatives as they otherwise could be used by the abusive ex partners in order to get to them. As such, the protected identity could mean an opportunity for a fresh start for the women, as a way to “knife off” destructive and criminogenic elements of their social surroundings (see [38, 45]). However, as the women are forcefully cut off from their entire social networks, pro-social and supportive contacts disappear as well, isolating the women. Stripped of their social networks and in a new environment, breaking the resulting isolation is a tough barrier to overcome (cf. [13, 22, 28, 52]). As a result, the women often found themselves stuck in a liminal position, having broken off from their past identities without being able to establish “new” identities as accepted parts of conventional society (cf. [52]). Louise reported her partner’s violence to the police, but it never led to prosecution. She then obtained her protected identity to get away from him. The years she spent living with a protected identity were not happy. She pointed out that the whole system is “crooked,” as it requires the victim to hide, while “It’s the abusers that should hide!” Furthermore, she said that

Louise: We are stripped of our whole lives for some fucking reason. And you know… yeah. While they can go on with their lives however they damn please. They don’t have to change a thing you know. They can stay where they live and… yes […] But we’re supposed to hide away in some unknown location and break off with basically everyone we know, or everyone you know that he knows/ […] Cause you can’t maintain contact with any of them, since you don’t want anything to happen to them.

This quote clearly shows the extensive social consequences of intimate partner violence, and how the effects linger on well after the violent relationship is over. Louise could let her protected identity go when her perpetrator received a long prison sentence (for crimes not involving her). However, she is still to this day cautious about her use of social media. She told me “Yes, I still take care not to accept friend requests from people who I know are a common/ [R: Yes?] That I do, actually. So I am still a bit cautious.” Although she no longer lives with a protected identity, she has kept the name she took in the process. When I met her, 16 years had passed since she escaped the abusive man. However, she still kept an eye on him, from a distance. She knows which city he lives in, and she tries her best to avoid it. Hence, intimate partner violence caused painful isolation for Louise, which still echoes back to obstruct her present desistance process. Consequently, echoes of intimate partner violence restrain her efforts to socialize in several settings, enhancing an already existing barrier to make it harder for her to meet people and establish pro-social contact networks needed to break the isolation. Social exclusion is a risk for women with convictions in general [58]. Involuntary knifing off of what little support network they had makes the women susceptible to further exclusion. Echoes of violent victimization reverberate to amplify barriers to the women’s efforts to socialize and form new social networks, which can escalate the exclusion and cause isolation, goal failure, and a sense of hopelessness. Thus, the echoes of violent victimization have social implications which can activate all three pains of desistance as suggested by Nugent and Schinkel [52].

The protected identities also present issues with the social services and the contact with other authorities. Louise elaborated on how “It’s really hard to/ just paying for stuff, or going to the doctor’s is a problem you know [R: Yes] Cause I just walk up to the social services and like make up my own social security number.” Sofia also pointed out several practical issues in keeping contact with governmental authorities that comes with a protected identity. As all of her mail has to go through a relay service, urgent bills have resulted in delay fees. She also spoke of difficulties obtaining her ADHD medication, as her prescription cannot be digitally stored with the pharmacy because of the risk of linking her social security number to her new and secret address. Complicating paying bills and obtaining the medication they need, the protected identity presents barriers to key aspects of conventional life, leaving them stuck in a liminal position not included in conventional society. These barriers could impede the women’s attempts at both identity and relational desistance. As common ways to interact with conventional society are hindered, the individual cannot be perceived by herself or others as part of it.

Another tangible effect of having survived previous intimate partner violence is a changed approach to new (intimate) contacts with men (cf. [40]). This theme is shared among many of the women. Johanna has had several abusive male partners in the past, and after seeing this abusive pattern repeat itself, she says her view of men as potential partners has shifted. She has now come to “kinda hate men.” When I asked her in a later interview if she envisioned some kind of intimate relationship to any man in her future, she simply responded “No,” followed by a determined:

Johanna: I’m not letting anyone into my house again [...] No one can move in with me. Never. [R: No? Alright] ... that ship has sailed [R: Yeah]. Yeah, I’ve only had bad experiences.

As such, engaging in new romantic relationships is a closed path to breaking the isolation. Contextualized against previous research on men, this means severe barriers to romantic relationships as potential facilitators of desistance (cf. [39]). Furthermore, this changed approach to relationships and social contact with men can even lead to a change in how the women perceive and feel about themselves. Louise elaborates on this. She says having lived in a close relationship with a violent partner has changed her as a person. This is most apparent in her (lack of) opportunities to meet and socialize with new people. Early on in our first interview she described herself in relation to other people, and she detailed: “But I do keep my distance to people, generally. Even though I’m perceived as super social I do keep my distance”. I asked her if this was a new personality trait, or if she had always been that way. She replied that it was a trait that she had embraced due to her history of arrest, compulsory treatment and her protected identity, when she was “totally isolated for several years, you know.” Continuing her narrative, she elaborated:

Louise: Yes. And that protected identity that I had for many years. It damaged me more than I’m actually aware of, I’ve noticed. [R: In what way then?] Well, just keeping my distance a lot more. I don’t have a need for people, when maybe I should have a need for people.

Louise’s notion that she “should” feel a need for people in general and romantic partners in particular could be linked to identity and relational desistance, as one way to be perceived by herself and others as part of conventional society could be through the normative notion of heterosexual monogamy (see, e.g., [1, 23]; also cf. [52]). Louise, being 43 and childless, deviates from the normative life script which proclaims family formation and togetherness. This is an example of how normative life scripts produce feelings of otherness, and how this hinder desistance by leaving women in a liminal position, no longer condemned by society but at the same time not accepted as part of it (cf. [37, 52]).

When we returned to this subject during our third interview, she elaborated on her feelings of a changed self, and more specifically about how being a victim of intimate partner violence had made her own behavior more violent:

Louise: Cause I actually notice how he has affected my life way more than maybe I/there aren’t that many harmful effects to pin on him. But he has affected my life in ways that I might not be fully aware of still, you know.

R: What are you thinking of then?

Louise: Well, how I handle situations. And how I react. And how I act myself. [R: Yeah] I feel like this psychopathic trait, I can take it on myself, you know. Treat people like… that. […] I’ve learned a behaviour from him. That maybe I never wanted to learn. […] And then... I still struggle with social things, social contacts, large crowds, you know. I still struggle with that.

The notion of having taken over psychopathic and violent personality traits from their abusive men is a painful one, and for some of the women it seems to be the most tangible and unwanted consequence that the violence has brought them. Maia echoes this:

Maia: I mean, I’m not a violent person [R: No] I’ve had violent things done to me, and now I feel like/I mean, I ‘m becoming/do you know what I mean? I see these traits in myself, the same ones I’ve been exposed to. I mean that is just/I don’t know what to do with myself.

Painful as this is, these quotes also emphasize how (abusive) romantic relationships can pull women desisters back towards crime and therefore pose barriers to desistance, as opposed to being facilitators as suggested by previous research conducted on men (cf., e.g., [39, 40]).

Health Consequences

Five of the women have documented PTSD clinically linked to recurring violent victimization in adulthood.Footnote 3 Among them, Sofia is the only one to have undergone psychological treatment for her condition. When asked if and how her experiences of being violently victimized affect her today, she pointed out that those psychotherapeutic sessions have helped her deal with her traumatic experiences and allowed her to get on with her life. She is grateful for her psychological treatment, as she is aware that many women who have experienced similar trauma caused by violent men have to wait for years before they can see a psychologist, if they ever get to see one. This is true for the majority of the women in this study. Let us now turn our focus to some of them.

Maia has documented PTSD and “complex trauma” resulting from a history of violence from multiple intimate partners. The worst of them was a man that she was with for 4 months. Their relationship ended with the man trying to throw Maia over the balcony on the fifth floor. At our first interview, she told me she did not want to talk about the violence that she had suffered. However, she did tell me that since she broke up with the man that she had her daughter with at the age of 17 she had had six boyfriends. Five of them were violent towards her. Her PTSD severely restricts her volition, with isolation as a direct consequence. In periods, she is even afraid to leave her apartment, resulting in painful isolation as suggested by Nugent and Schinkel [52]. She told me of her anxiety, how it can make her spend her nights sitting in her apartment screaming and cursing for hours. She does not dare to leave her home during these “seizures” as she calls them, as she is afraid that she might actually hurt someone who would get in her way. This again is a reminder of how (past) intimate partner violence can work in criminogenic and/or isolating ways to obstruct processes of desistance. When I met her for our first interview, Maia had voluntarily moved from her apartment into supported housing because she needed help and was afraid she might lose her apartment otherwise. At one time, a neighbor had come down to her, asking her to “calm down” and “maybe seek psychological assistance.” She told the neighbor that she had sought such assistance on multiple occasions. She then elaborated to me on her experiences of her encounters with the psychiatric care system:

Maia: I never get the right help. Instead it’s just/Punishment! [R: Yes, right]. It feels like I’m being punished! I can’t ever get anywhere, it’s just like… [sigh] Okay. I have to keep fighting, no matter if I’m drug free or if I’m using [...]

R: No matter what, yes. Cause I was thinking that if you’re on amphetamines then that’s all they’re focused on?

Maia: Yes, and the psychiatric care doesn’t want anything to do with me when I’m abusing. I have to deal with the abuse first. [R: No, I know] And they all talk about coordinating but it’s just talk. There’s nothing that works. There’s no coordination! They don’t even e-mail each other! They ask me: “Have you been in contact with the psychiatric care?”

She has been in contact with the psychiatric care system many times, and every time she has gotten her hopes up, the (lack of) response has resulted in multiple goal failures and subsequently a feeling of hopelessness when it comes to achieving relief for her psychological torments. When I asked her how she has experienced the meetings with the psychiatric care system, she told me:

Maia: The psychiatric care system just wants to medicate me. […] There’s no therapy, no treatment, nothing. The two times that I was in trauma treatment they told me I had complex trauma. So perhaps not even they could help me. They asked me if I’d gotten any help, psychotherapy or something [R: Yes?] I have never been offered psychotherapy. [R: You haven’t?] No, nothing.

The complex trauma has brought Maia to experience both isolation, goal failure, and hopelessness. She is thus experiencing all three of the pains of desistance as identified by Nugent and Schinkel [52]. She also talked about how her situation as a drug using trauma patient has her sent between the psychiatric care system and the social service system (this finding is in line with the literature on the challenges of dual diagnosis; see, e.g., [54]). The psychiatric care system wants to medicate her trauma, but she is not receptive to medications due to her abuseFootnote 4 of narcotic drugs. Hence, Maia felt she was “falling through the cracks” as she was too mentally unstable to get off the drugs, and too attached to the drugs to be treated for her mental illness. When I first met her in the summer of 2016, Maia had been waiting to see a psychiatrist for over a year. During the time I got to follow her struggle towards desistance, she went through two major drug relapses that also brought other criminal activities back into her life. Both relapses were due to Maia not getting the trauma therapy she required. This is a telling example of how pains of desistance put great stress on desistance journeys.

Kate also has documented PTSD, resulting from multiple traumatic experiences. Her trauma included violent victimization from several intimate partners, but also her witnessing first-hand how two different partners died from drug overdoses in her home within months of each other. When we met for our third interview, she told me she had relapsed, using heroin for a brief period following Christmas and New Year. To buy the heroin, she also relapsed into theft, and she was subsequently caught with stolen goods worth a total of 10,000 SEK.Footnote 5 This relapse occurred after she had felt her progress had stalled. As such, it is an example of how repeated goal failures led her to a state of hopelessness (cf. [52]; see also [25] for further theorizing on hopelessness and relapse within desistance processes). The multiple goal failures included failed attempts at breaking the isolation she found herself in, along with a stalled progress in acquiring employment and repeated and failed attempts at obtaining trauma treatment. At first, she was sent to a psychiatrist to obtain help (in the form of medication) for her ADHD. However, once there, she was told that the medication they could offer would do her no good due to her specific needs. She told me:

Kate: And then I haven’t felt good. I’ve had so much anxiety, stress, PTSD. I mean, all of that. And I’ve gotten no help from outside you know? I left (a psychiatric reception) [R: Yeah] Because they were/I had this… ADHD-thing. That’s how I got there. [R: Mhm] And then we kind of decided that I shouldn’t be there [R: Aha?] Cause only thing they do is give ADHD-medication. And I’ve already tried that medication. And most of the time it works on boys, but it could work on some girls if they have pure ADHD [R: yes] No problems with anxiety. No PTSD. […] So what she said then was basically that “no, we have no help here, besides that”. [...] And she said “you won’t get no help here, cause this is what it is.”

When I asked her whether the social services have helped her with her illness, she replied “No, they haven’t been involved at all really. Apart from giving me financial aid.” She did however obtain housing support, to help with cleaning and dishwashing. But when the social services found out that they were talking to each other more than cleaning, the support was canceled. Hence, an opportunity to break the isolation Kate found herself in was taken away from her, leaving Kate with a new goal failure and continued isolation. Kate told me:

Kate: I applied for housing support myself. But then when she got here she said “no, I’m not really what you need. What you need is/ because you have/” and then she told me I had PTSD and anxiety, too, haha! [R: Alright] And she sat down and tried to be a counsellor [R: Sure]. But then soc [social services] said: (using a high-pitched voice) “well, that’s not what the housing support is there for.”

Just like Maia, Kate talked about seizure-like symptoms of the PTSD, putting her in a state where she could not deal with her everyday life. This is what she means happened before Christmas, following the failed attempts to obtain trauma treatment, along with failure to obtain employment and to break the state of isolation. She told me those seizures can last for a day, with physical symptoms such as a rushing heart and hyperventilation along with a more psychological anxiety and a fear or even “horror” of meeting people, or picking up and leaving her daughter at day care.

Kate’s experiences are examples of how health issues arising from intimate partner violence (and other aforementioned trauma) was impairing her ability to function in her everyday life. The isolation often found among desiters (cf. [52]) is becoming an even more difficult obstacle to overcome as the trauma from past violent victimizations from intimate partners echo to amplify the stressful situation. This, together with the fact that Kate now took to theft to finance her heroin intake, further the point stressed throughout this paper that intimate relations to violent partners can have a lingering criminogenic effect that place barriers to the desistance process of the victim. Before her desistance, Kate (along with several of the women) had tackled her anxiety by using narcotic drugs as a form of self-medication (cf. [36, 65]). However, once off drugs, it becomes apparent that the women suffering from the symptoms of PTSD are in need of trauma treatment in order to function in their everyday life, and to not get stuck in a liminal position but instead take the steps necessary to achieve act, identity, and relational desistance (cf. [52]).

It is also apparent that the treatment of psychological illnesses must be customized to fit the specific needs of the women. Kate, Sofia, Maia, Louise, and Nina all have ADHD along with their PTSD. In some cases, additional mental deficiencies and disorders further complicate matters. In addition to this, consideration has to be given as to the women’s living conditions. Nina provides an example of this.

Nina has three children together with a man she describes as “a retired hitman”. Violence formed a core part of his life and actions, and this violence was equally present within and outside the home as he regularly victimized Nina and their children. She broke off from him after he tried to burn down her house. Before that, she had also witnessed him being shot and severely injured. Such traumatic experiences (along with others) resulted in clinically documented PTSD for Nina. When she left the hitman, she lived in several different women’s shelters for around 8 months, before finally being permanently relocated to a new part of the country where she also obtained a protected identity. During the 8 months in different women’s shelters, she was entitled to psychiatric counseling; however, this never commenced. Living in such uncertain circumstances, already suffering from stress while also having sole custody of her three children (one of which was in need of extra care due to complications at birth), she said she just was not able to go into counseling. When we discussed why her entitled counseling never commenced, she said:

Nina: No, I was pretty busy with my kids. […] So “what do you mean, therapy?” you know? In that case you need a stand-in at home and stuff [R: Yes] Or they need to come home to you for therapy sessions, haha! [R: Yes. Right] Living the way I did. […] So yeah no, that never got done anyway.

After this period of sheltered accommodation and protected identity, Nina was sent to prison for assaulting a police officer. Nina’s experiences are examples of how the ability to desist is fragile and can easily become compromised by any barriers obstructing the desister’s agentic efforts. Nina was unable to attend the trauma counseling that she was entitled to due to her living conditions and childcare responsibilities at the time. As a result of this, at the time of our forth interview (about one and a half year after serving the prison sentence), she was still waiting for treatment for the trauma caused by her violent intimate partner. Nina strongly felt that she was obstructed or even opposed by the authorities, and therefore severely restricted in her search for a sense of belonging in conventional society and to achieve identity as well as relational desistance (cf. [52]).

Concluding Discussion

Drawing on repeated and qualitative interviews with women striving towards desistance from crime, this article has discussed how echoes of intimate partner violence work as a hindrance in women’s desistance processes. All women in this study have experienced intimate partner violence in the past. Although none of them lived with an abusive partner at the time for the interviews, it is clear that the violence and trauma that they suffered in the past has prolonged effects that result in severe implications for the women’s desistance processes.

The impairments to women’s ability to act on their will to desist from crime are linked to both social and health related consequences of past violent victimization. The analysis shows how intimate partner violence pushes desisters towards a painful state of isolation, which can be destructive for the desistance process, hindering attempts to (re)connect to conventional society (cf. Nugent & Schinkel; This finding also support the results of Holmberg et al. [28] as well as Eliasson [13]). In some cases, victims of intimate partner violence obtain protected identities in order to escape their perpetrators. However, protected identities also place severe restrictions on an individual’s social life, including relocation to new cities, abandoning names, friends, and even relatives as well as an inability to make full use of social media. The results presented in this article also show that such restrictions can be in place long after the protected identity is lifted, sustaining the isolation that originated from the intimate partner violence so that it continues to affect the victim long after the violent relationship has ended. Furthermore, the results show how past experiences of intimate partner violence restrict women’s agentic attempts at desistance by constraining their efforts to interact with conventional society. As such, victimization and prolonged periods of isolation leave the desister uneasy in terms of socializing and meeting new people, keeping her stuck in a liminal position as she has left her old life and (criminogenic) social networks without being able to connect to prosocial networks and conventional society. Hence, intimate partner violence has long term social effects that obstruct the victim’s efforts to achieve identity and relational desistance (cf. [52]). Several women said that their perception of men as potential intimate partners had changed, and some women reported feeling uncomfortable or unsafe meeting new people at all, regardless of their gender, meaning that the pathway out of crime via romantic relationships has been obstructed, and that the women are left in a state of isolation (cf. [39, 52]). This finding is important, as it emphasizes a vicious cycle. The link between disadvantaged upbringings, low socioeconomic status, drug misuse, offending, and violent partners among women with offending histories have been clearly made in previous research. This study stresses the importance of holistic and coordinated support from different sections of society, such as the psychiatric care system, the social services, and the criminal justice system in order to break this vicious cycle and make it possible for women with offending histories to (re)connect with society and escape recurring victimization as well as relapses into drug use and other crime.

Concluding the discussion on social consequences is the grim, but important, notion discerned by some women that they have acquired a changed self-conception due to the violence that they have suffered. Still reliving the horrors of past violent victimization, they now also see features and personality traits in themselves that remind them of their psychopathic and violent ex partners. This apparition further restricts the women’s will and ability to engage in new (pro-)social relations. Thus, past experiences of intimate partner violence can be criminogenic and/or lead women desisters into states of isolation. Echoes of intimate partner violence amplify existing barriers to women’s desistance processes (cf. [52]). This is a theoretically important finding as it further supports the understanding that relationship formation plays a different role for women’s desistance than what has been suggested by research on male samples (cf., e.g., [39, 55]).

This article has also discussed long-term (mental) health consequences of violent victimization and their influence on women’s abilities to desist from crime. The most notable consequence in this regard is that the traumatic experience of having repeatedly been violently victimized by intimate partners has led to PTSD for five women, which comprises half of the sample in this study. These diagnoses were clinically linked to the women’s recurring experiences of IPV in adulthood. However, several of the women also shared histories of childhood trauma, and although neither the women nor these clinical diagnoses emphasized it, the role of cumulative trauma is likely to also influence the life course in general, and attempts at desistance specifically. The PTSD (in combination with other ailments such as ADHD) is adding to the isolated state that women find themselves in when trying to desist from crime. Stressful situations such as socializing, meeting new people or even moving outside the home can trigger seizure-like symptoms of post-traumatic stress and anxiety, further complicating already difficult approaches to (re)enter conventional society. Isolation is a common pain among desisters [52], and this paper has shown how echoes of intimate partner violence reverberate off of this barrier to make a stressful situation even harder to overcome. As the women all expressed the will to change their lives and to (re)connect with society, an inability to break the isolation by acquiring employment or prosocial peer relations can result in experiencing (repeated) goal failure. Goal failure in combination with isolation can lead to a state of hopelessness, putting already fragile desistance processes at great risk of a relapse into drug use and other crime. As such, echoes of violent victimization can work as a hindrance in women’s desistance processes by actualizing all three of the pains of desistance proposed by Nugent and Schinkel [52].

This study followed women desisters while they were all involved in early stages of their desistance processes. The majority of the research on desistance has been conducted retrospectively and is thus capturing more “final” or stable stages of desistance, after the process actually has brought on a changed lifestyle with a more stable decrease in (or termination of) offending (see, e.g., [38, 44]). My research highlights the fragility that is involved in these early stages of desistance, and more research is required to increase the understanding of how desistance processes might be built on phases or stages. Such research would increase our understanding of the complexity of desistance processes as a whole. In so doing, desistance research could develop to inform better-adapted intervention methods to increase the ability for people willing to desist to actually act on that will.

The results presented in this study also challenge a number of key issues with contemporary life-course criminology. As stated in the introduction, much desistance research (on men) has emphasized the importance of a romantic partner as facilitating desistance from crime ([55]; see also [39]). The applicability of such findings for understanding women’s desistance have been problematized (see, e.g., [55]), and this article further challenges this notion. Violent victimization from intimate partners has been linked to pathways into crime [11], and the present study has shown how violence from intimate partners can work as a hindrance or barrier to pathways out of crime as well. Hence, this finding undermines the claim that factors influencing onset are different from factors influencing desistance from crime. Challenging the notion of partners as facilitators of desistance, this article also emphasizes the need to study women’s life courses in order to fully understand the complex phenomenon that is desistance from crime.

Furthermore, another central aspect in desistance theory is the notion of knifing off of old peers as a key in desistance processes [38, 45]. A period of isolation can be necessary for the change in lifestyle that is required for desistance from crime (cf. [20]). However, as shown in this study, intimate partner violence can cause unwanted knifing off of friends and relatives that otherwise could have offered support for the individual. Having been involuntarily stripped of all social support, structural barriers to desistance can prove near impossible to overcome for women with a criminal past, resulting in prolonged isolation, goal failure, and hopelessness. As such, this study highlights the dangers of escalating social exclusion for individuals leaving a criminal lifestyle behind, and efforts should be made to aid desisters’ attempts to socialize and meet new people to break the isolation brought on by the process of knifing off. The concept of knifing off still is undertheorized, and more research is needed to develop our understanding of the mechanisms of desistance.

The concept of echoes amplifying already tough barriers to desistance serves to underline the complexity involved in desistance processes, and by doing so it also challenges a (too) simplistic approach present in contemporary desistance theory. Within this theoretical tradition there seems to be an over-reliance on the importance of agency for desistance; implying that a willing desister is an able desister. To further develop the understanding of barriers to desistance, future research should focus on how to make theory account for the complex relation between an individual’s will to desist and her actual ability to act on that will.

Notes

The adverts were written in Swedish, which may have played into the fact that all ten women who participated in the study was of Swedish or other Scandinavian ethnicity. The prison adverts had the additional condition that anyone interested in the study should have no more than 6 months left to serve on her sentence, as I wanted to follow her efforts to reconnect with society post-sentence.

The last official figures from the authorities monitoring protected identities in Sweden came in 2008, stating that more than 11,000 people live with protected identities. Most protected identities are given to protect women who are being threatened or stalked by (previous) intimate partners, as is the case for the women in this study. A protected identity usually lasts 2 or 3 years, with the possibility for extension if the need persists [61].

A sixth woman, Doris, was diagnosed with PTSD between our third and fourth interview. However, in contrast to the five women whose narratives are analyzed in this section, this related primarily to childhood trauma and abusive (foster) parents. Thus to provide focus in the analysis, Doris’ narrative is excluded here. The impact of cumulative trauma is instead discussed in the conclusion.

The choice of using abuse or use of drugs is dependent on how the women frame their drug intake.

Approximately 1200 US dollars.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology. Orientations, objects, others. Durham: Duke University Press.

Alexander, P. C. (2009). Childhood trauma, attachment, and abuse by multiple partners. Psychological Ttrauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(1), 78–88.

Band-Winterstein, T. A., & Eisikovits, Z. (2014). Intimate violence across the lifespan. New York: Springer.

Benedini, K. M., & Fagan, A. A. (2017). A life-course developmental analysis of the cycle of violence. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, online first, pp 1–23.

Bersani, B. E. & Doherty, E. E. (2018). Desistance from offending in the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Criminology, in press

Burnam, M. A., Stein, J. A., Golding, J. M., Siegel, J. M., Sorenson, S. B., Forsythe, A. B., & Telles, C. A. (1988). Sexual assault and mental disorders in a community population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 843–850.

Campbell, J. C. (1992). “If I can’t have you, no one can”: power and control in homicide of female partners. In J. Radford & D. E. H. Russel (Eds.), Femicide: the politics of woman killing (pp. 99–113). New York: Twayne Publishers.

Carlsson, C. (2014). Continuities and change in criminal careers. Dissertation. Stockholm: Stockholm university, Department of Criminology.

Cherlin, A., Chase-Lansdale, L., & McRae, C. (1998). Effects of parental divorce on mental health throughout the life course. American Sociological Review, 63(2), 239–249.

Chesney-Lind, M., & Pasko, L. (2013). The female offender: girls, women, and crime. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Daly, K. (1992). Women’s pathways to felony court: feminist theories of lawbreaking and problems of representation. Southern California Review of Law and Women’s Studies, 2(1), 11–52.

DiPietro, S. M., Doherty, E. E., & Bersani, B. E. (2018). Understanding the role of marriage in black women’s offending over the life course. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, Online first, pp 1–26.

Eliasson, M. (2011). Mäns våld mot kvinnor: en kunskapsöversikt om kvinnomisshandel och våldtäkt, dominans och kontroll. [Men’s Violence against Women: a Review on Violence against Women and Rape, Dominance and Control]. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

Ellis, D. (1994). Estrangement, interventions and intimate femicide. In Fifth symposium on violence and aggression, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, pp 19–22.

Farrall, S., & Bowling, B. (1999). Structuration, human development and desistance from crime. British Journal of Criminology, 39(2), 253–268.

Farrall, S., & Calverley, A. (2006). Understanding desistance from crime: theoretical directions in rehabilitation and resettlement. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Farrall, S., Bottoms, A., & Shapland, J. (2010). Social structures and desistance from crime. European Journal of Criminology, 7(6), 546–570.

Farrall, S., Hunter, B., Sharpe, G., & Calverley, A. (2014). Criminal careers in transition: the social context of desistance from crime. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garcia-Moreno, C., Pallitto, C., Devries, K., Stöckl, H., Watts, C., & Abrahams, N. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich, A., & Rudolph, L. J. (2002). Gender, crime and desistance: toward a theory of cognitive transformation. The American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 990–1064.

Gould, A. (2001). Developments in Swedish social policy: resisting Dionysus. New York: Palgrave.

Gray, P., Simmonds, L. & Annison, J. (2016). The resettlement of women offenders: learning the lessons. Plymouth University: Criminology and Criminal Justice.

Halberstam, J. (2005). In a queer time and place. Transgender bodies, subcultural lives. New York: New York University Press.

Halsey, M., & Deegan, S. (2015). Young offenders: crime prison and struggles for desistance. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Halsey, M., Armstrong, R., & Wright, S. (2016). “F*ck it!”: Matza and the mood of fatalism in the desistance process. British Journal of Criminology, 57(5), 1041–1060.

Hart, B. (1988). Beyond the “duty to warn”. A therapists “duty to protect” battered women and children. In K. Yllö & M. Bograd (Eds.), Feminist perspectives on wife abuse (pp. 234–248). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Hitlin, S., & Elder, G. H. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170–191.

Holmberg, C., Smirthwaite, A., & Nilsson, A. (2005). Mäns våld mot missbrukande kvinnor, ett kvinnofridsbrott bland andra. [Men’s Violence against Women Abusers]. Stockholm: Mobilisering Mot Narkotika.

Hunter, B., & Farrall, S. (2018). Emotions, future selves and the process of desistance. British Journal of Criminology, 58, 291–308.

Irving, S. M., & Ferraro, K. F. (2006). Reports of abusive experiences during childhood and adult health ratings: personal control as a pathway? Journal of Aging and Health, 18(3), 458–485.

Jacobs, A. L. (2001). Give ‘em a fighting chance: women offenders re-enter society. Criminal Justice, 16(1), 44–47.

Jarnling, P. (2004) Om våldsutsatta, missbrukande kvinnors situation—undersökning av erfarenheter och arbetssätt på kvinnojourer respektive behandlingshem för missbrukare. [On Victimized, abusing women’s situation—investigation of experiences and ways of working in women’s shelters and treatment centers for abusers]. Stockholm: Alla kvinnors hus.

Jasinski, J. L., Wesely, J. K., Wright, J. D., & Mustaine, E. E. (2010). Hard lives, mean streets: violence in the lives of homeless women. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Kilpatrick, D. G., Saunders, B. E., Veronen, L. J., Best, C. L., & Von, J. M. (1987). Criminal victimization: lifetime prevalence, reporting to police, and psychological impact. Crime and Delinquency, 33(4), 479–489.

Laanemets, L. (2002). Skapande av femininitet: om kvinnor i missbrukarbehandling. [creation of femininity: on women in drug treatment]. Lund: Socialhögskolan.

Lander, I. (2003). Den flygande maran. En studie om narkotikabrukande kvinnor i Stockholm. Department of Criminology, Stockholm University.

Lander, I. (2015). Gender, aging and drug use: a post-structural approach to the life course. British Journal of Criminology, 55(2), 270–285.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Laub, J. H., Nagin, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (1998). Trajectories of change in criminal offending: good marriages and the desistance process. American Sociological Review, 63(2), 225–238.

Leverentz, A. M. (2006). The love of a good man? Romantic relationships as a source of support or hindrance for female ex-offenders. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 43(4), 459–488.

Macmillan, R. (2000). Adolescent victimization and income deficits in adulthood: rethinking the costs of criminal violence from a life-course perspective. Criminology, 38(2), 553–588.

Macmillan, R. (2001). Violence and the life course: the consequences of victimization for personal and social development. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 1–22.

Maher, L. (1997). Sexed work: gender, race and resistance in a Brooklyn drug market. New York: Oxford University Press.

Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: how ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Maruna, S., & Roy, K. (2007). Amputation or reconstruction? Notes on the concept of “knifing off” and desistance from crime. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(1), 104–124.

Matza, D. (1969). Becoming deviant. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

McNeill, F. (2006). A desistance paradigm for offender management. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 6(1), 39–62.

Messerschmidt, J. W. (1993). Masculinities and crime: critique and reconceptualization of theory. Boston: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Miller, J., & Schwartz, M. D. (1995). Rape myths and violence against street prostitutes. Deviant Behavior, 16(1), 1–23.

Nilsson, A., & Tham, H. (1999). Fångars levnadsförhållanden: resultat från en levnadsnivåundersökning. Norrköping: Kriminalvårdsstyrelsen.

Nilsson, A., Bäckman, O., & Estrada, F. (2013). Involvement in crime, individual resources and structural constraints. processes of cumulative (dis)advantage in a Stockholm birth cohort. British Journal of Criminology, 53(2), 297–318.

Nugent, B., & Schinkel, M. (2016). The pains of desistance. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 16(5), 568–584.

Phillips, J. (2017). Towards a rhizomatic understanding of the desistance journey. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 56(1), 92–104.

Ridgely, M. S., Goldman, H. H., & Willenbring, M. (1990). Barriers to the care of persons with dual diagnoses: organizational and financing issues. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(1), 123–132.

Rodermond, E., Kruttschnitt, C., Slotboom, A.-M., & Bijleveld, C. (2016). Female desistance: a review of the literature. European Journal of Criminology, 13(1), 3–28.

Rosenbaum, M. (1981). Women on heroin. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Sampson, R. J. & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points through Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sharpe, G. (2015). Precarious identities: “young” motherhood, desistance and stigma. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 15(4), 407–422.

Sharpe, G. (2016). Re-imagining justice for girls: a new agenda for research. Youth Justice, 16(1), 3–17.

Sharpe, G. (2017). Sociological stalking? Methods, ethics and power in longitudinal criminological research. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 17(3), 233–247.

Skatteverket (2008). Skyddade personuppgifter [Online]. Available at: https://archive.is/20090808200248/http://www.skatteverket.se/nyheterpressrum/pressrum/regionalapressmeddelanden/2008/2008/alltvanligaremedskyddadidentitet.5.3a7aab801183dd6bfd38000139. Accessed 10 March 2007.

Taylor, A. (1993). Women drug users: an ethnography of a female injecting community. New York: Oxford University Press.

Turner, R., Wheaton, B., & Lloyd, D. (1995). The epidemiology of social stress. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 104–125.

Vandevelde, S., Vander Laenen, F., Van Damme, L., Vanderplasschen, W., Audenaert, K., Broekaert, E., & Vander Beken, T. (2017). Dilemmas in applying strengths-based approaches in working with offenders with mental illness: a critical multidisciplinary review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 32, 71–79.