Abstract

Purpose

Recent work has suggested that specialization is correlated with frequency of offending, but this observed relationship may actually depend on the measuring instrument used. The diversity index is a common method of measuring specialization in such studies, and this paper investigates whether this observed correlation is due in part to the mathematical form of the diversity index itself. The criminological question as to whether specialization increases or decreases with offense frequency cannot be answered until the behavior of the diversity index is better understood.

Methods

We use simulations to investigate the behavior of the diversity index where the number of crimes is small (the small sample problem), simulating from known distributions of offending. Two of the distributions used in the simulation are defined to be unspecialized. The first uses an equiprobable distribution of offenses across offense categories. The second uses the distribution of offenses in the British population. The third distribution is from a specialist distribution and assumes that different offenders have different probabilities of choosing particular offenses.We report these simulations for both three and ten crime categories. To set the simulated results in context, we use an extract from the UK Police National Computer to investigate the criminological question as to whether specialization increases with offense frequency.

Results

For all three simulation schemes, the diversity index D increases steeply with the frequency of offending N at low frequencies, with the increase slowing around N = 20, and becoming flat when the number of offenses N reaches 500. This relationship is observed for both three crime categories and ten crime categories. The observed relationship of D with N can be used to correct the diversity index to allow the true relationship of specialization with offense frequency to be investigated.

Conclusions

We recommend that the diversity index be used with caution when there are small numbers of crimes over fixed time periods. Any increase or decrease of the diversity index over the criminal career life course may reflect the behavior of the measurement tool with the number of offenses, rather than any change in specialization itself. Applying one of the suggested suitable correction methods to D will mitigate this problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper is concerned with the statistical properties of the diversity index—currently one of the most popular methods for measuring and assessing specialization in criminological studies. The paper will investigate whether the diversity index varies according to the number of crimes N used to calculate it. If the index itself depends on N, then we need to be careful in making statements about how specialization varies with the number of crimes if the diversity index is used to measure it. In addition, care needs to be taken about making statements about the changing specialization of offenders over the life course if the diversity index is used to make such statements.

This topic is important as it is of criminological interest to know whether specialization in offending changes according to other criminological factors. For example, it is of interest to know whether specialization changes as an offender becomes older. However, we know from work on the age crime curve that the frequency of offending changes over the life course, reaching a peak in late adolescence before declining. A second example is to examine whether females are more specialized than males, but male offenders on average have a higher offense frequency compared to female offenders. If our measuring instrument for specialization depends on offense frequency for both of the above examples, then we cannot examine these questions without modifying the instrument. We expand on this point later.

Specialization is an important component of criminal career and life course research. Early studies of specialization suggested that it should be defined as the tendency to commit the same type of crime in consecutive offenses [17] and measured by the use of the Forward Specialization Coefficient [21]. Schreck [19] notes that there has been a move away from this definition, and specialization “now includes the diversity of crimes an offender commits”. Thus, individuals who have a wide range of offending would be diverse or versatile, where individuals with a more restricted range of types of offending would be specialist. Schreck [19] identifies that research using this broader definition of specialization has tended to show more consistent support for specialization. This conclusion is supported by DeLisi and Piquero [6] in their state of the art review, whose main conclusion is the existence of short term specialization in the midst of versatility.

This broader definition of specialization has tended to be measured by the diversity index. Introduced into the criminological literature by Piquero et al. [18] and Mazerolle et al. [11], its advantages are threefold: it offers an individual measure of specialization, it can be assessed for fixed time periods, and is well established in the statistical literature. Sullivan et al. [23] reviews specialization methodologies and highlights work by McGloin et al. [12] in identifying that the diversity index is advantageous in providing a way of comparing relationships between specialization and other theoretically relevant variables through regression methods. Such work has been carried out by both Sullivan et al. [22] and Nieuwbeerta et al. [15].

Additional approaches to specialization were also identified by Sullivan et al. [23] in their review. The first broad approach is that of latent class analysis. Francis et al. [7] proposed that the existence of more than one latent class when examining patterns of crime across crime categories suggested criminal lifestyle specialization; that some offenders specialize in some types of crime and not in others. The second broad approach takes a generalized linear modeling approach to specialization. For example, Osgood and Schreck [16] have proposed a binary multilevel model which assesses specialization towards violence through parameters in the model. In a similar vein, Deane et al. [5] has suggested a marginal binary logistic generalised estimating equation (GEE) approach for assessing specialization through the dependence of one crime type on other crime types, and Armstrong and Britt [2] have suggested a multinomial logit model for assessing changes in crime specialization over time. However, these approaches lie beyond the focus of this paper and our focus here is on the diversity index.

The diversity index was proposed as a statistical measure by Simpson [20], in the context of ecological samples and diversity of organisms. The context of this original form of the index is slightly different as the number of different types of organisms tend to be unknown at the start of ecological data collection. In criminological studies, in contrast, the categories of crime are normally determined a priori. In addition, the total count of organisms N is usually quite large in ecology studies, whereas in criminological studies, N can be quite small for some offenders.

We introduce some basic notation. If there are J crime categories, and N crimes (or offenses) are observed over a period of time, with n j being the number of crimes in crime category j, and with \(\sum n_{j} =N\), then the diversity index D is defined by

where \(\hat {p}_{j}\) is defined to be n j /N, the observed proportion in crime category j. The smallest achievable value of D is zero, representing complete specialization; the maximum is \( \frac {(J-1)}{J} \). This has led some researchers to suggest that an adjusted measure \(D^{*} = \frac {J} {(J-1)}\times D \) be used. However, this is only necessary if the number of categories J varies within a study.

Investigations into the statistical properties of the diversity index have been limited. The most important of these has been carried out by Agresti and Agresti [1] over 35 years ago. This study looked at the large sample properties or asymptotic behavior of the index (N large or infinite), but did not look at its small sample behavior. It is unclear from the paper what “large” means. As most criminological uses of the diversity index have small to medium sized samples of N<100, then it is clear that more work is needed to align knowledge about the index with how it is used in practice. Other researchers have criticised the diversity index in general terms. Nieuwbeerta et al. [15] state that calculating diversity index D is difficult when offense frequency is sparse, and Osgood and Schreck [16] identify that D does not account for “baseline” offending patterns (i.e., offending probabilities will differ across crime categories for the population under consideration).

Thus, while the diversity index is, on the face of it, a good measure of specialization (i.e., it has face validity and is believable by researchers), there are more formal desirable characteristics of the index that need to be present for the index to have content validity. One of the most important of these is that the index should be invariant to the number of crimes N. A number of papers [22, 23] have mentioned the limitations of the diversity index and its relationship with N, but a more systematic study is needed.

Turning to the relationship between true specialization and offense frequency, opinions have been mixed. Theoretical considerations suggest that specialization decreases with frequency. Thus, Piquero et al. [18] refers to self-control theory [10], which suggests that there would be more versatility in individuals with low self-control (who would have high offending frequency) although this direct relationship is not tested. Early work using self-report data has found empirical evidence that diversity increases with offense frequency [4]. However, [3], in a careful analysis and using the [17] definition of specialization, found no evidence of changing specialization with frequency. Work using the diversity index as a measure of specialization however has come to different conclusions from [3]. Sullivan et al. [22] refers to Moffitt’s theory [13, 14], where life-course persistent offenders are posited to have a greater range of offending and to offend more frequently than adolescent-limited offenders. They found that versatility (as measured by D) did increase with frequency of offending. McGloin et al. [12] found a highly significant relationship between D and offense frequency. It it not clear whether these later results are due to the change in measuring instrument. If there is a relationship between the index D and frequency, is there still empirical evidence of these theoretical relationships?

The possible dependence of D on N is important for other reasons apart from the relationship between offense frequency and specialization. There is substantial interest in the relationship between specialization and other criminological variables such as age or life course events, or the comparison of the degree of specialization across different types of offenders. We highlight three of the papers above as examples.

Sullivan et al. [22] examined the relationship between diversity and the size of the fixed time period examined (the window size), positing that specialization is a short-term effect in a more general career of versatility. In their analysis, there was a control for frequency by stratifying into four groups according to total number of crimes. However, this control is rather crude, as the choice of frequency categories varies according to window size (1 month, 1 year, or 3 years). Thus, a better control method for frequency may be needed if such a relationship between diversity and frequency exists, and this may change the results.

Nieuwbeerta et al. [15] were interested in the relationship between specialization and age and notice that “general theories of crime acknowledge a positive association between offense frequency and versatility”. In their analysis of the Netherlands Criminal Careers and Life-Course Study, there was no control for frequency, although smoothing was applied to both the number of crimes of a particular type, and the total number of crimes. The issue is therefore that control for the total number of crimes in a particular time point may be needed in this study if a relationship between the diversity index and offense frequency exists. The fact that their measure of diversity reaches its peak value when the total number of crimes is highest—at around the age of 25 suggests that this relationship may be present.

Finally, McGloin et al. [12] was interested in the relationship between specialization and local life course events. A longitudinal random effects regression model was specified, modeling the diversity index against time-varying covariates such as marriage, drug use and alcohol use, and controlling for offense frequency by including N as a time-stable covariate. McGloin et al. [12] finds a significant linear relationship of diversity with frequency which is highly significant. Our interest here is whether the relationship between diversity and N is truly linear, and whether better control could be achieved by transforming either the diversity index or the frequency of offending.

Examining the Relationship Between the Number of Crimes and the Diversity Index

Our aim in this section is to investigate whether the measuring instrument of the diversity index D is related to the number of crimes N used to calculate it, and whether this also varies with the number of crime categories J. We are particularly interested in the small-sample behavior of D, that is, when N is small. To do this, we calculate the expected or mean values of D under known properties, allowing both N and J to vary. We wish to do this while holding constant the degree of specialization over N and J, so that any observed change in the diversity index cannot be due to changes in specialization.

For certain simple scenarios, it is possible to calculate the mean or expected value of D theoretically. For example, for J=3 crime categories which have equal probabilities of 0.333, there are just three possibilities: either all of the crimes fall into one category, or each of the crimes falls into a different category, or two of the crimes fall into one category and the remaining crime into another category. We can calculate the diversity index and the probability that each of these events occurs:

-

All of the three crimes fall into one category The diversity index is 0.0, and the probability that this occurs is (0.3333)2=0.1111.

-

All of the three crimes fall into a different category. The diversity index is 1−(1/3)2−(1/3)2−(1/3)2=0.6667 and the probability that this occurs is 0.3333×0.6667=0.2222.

-

Two of the three crimes fall into one category and the remaining one into a second category The diversity index is 1−(1/3)2−(2/3)2=0.4444 and the probability that this occurs is one minus the probabilities of the other two possibilities: 1−0.1111−0.2222=0.6667.

The expected or mean diversity index is therefore 0.1111×0+0.2222×0.6667+0.6667×0.4444=0.4444. However, when we increase the number of crimes, and also allow the probabilities of crime in the various categories to be unequal, then such probability calculations become onerous. We therefore resort to simulations. Jumping ahead, we will see that the simulated average diversity index for J=3 and N=3 under the assumption of equiprobable crime categories is 0.4445, which is almost identical to the theoretical value produced above. Thus, providing the number of simulations is large, then the estimate of the mean diversity will be highly accurate.

We therefore carry out simulations in order to examine the relationship between the diversity index and N for small samples. We choose two popular crime categorisations. The first has ten crime categories. We assume, following the example from [9] below, that these are violence against the person, sexual offenses, robbery, burglary, theft, and handling stolen goods, fraud and forgery, drug offenses, criminal damage, driving offenses, and other offenses. While we have named these ten categories, the labels are arbitrary. The second categorisation uses three categories, and we assume that these are violence (comprising violence, sexual offenses, and robbery), property (comprising burglary, theft, fraud, and criminal damage) and other (comprising drug offenses and other offenses) following the categorisation used by Nieuwbeerta et al. [15].

For each choice of crime categorisation, we choose three different distributions of crime (the baseline category probabilities) which remain unchanged as the frequency changes.

-

1.

The first scheme has an equiprobable distribution, assuming that each crime category has the same probability of occurring. For J=10 crime categories, this gives a probability of 0.1 for each category. This is an unspecialized scheme.

-

2.

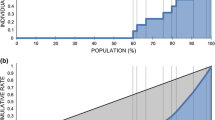

The second scheme assumes that all offenders are sampled from the distribution of crime which occurs in the general population. This is also an unspecialized scheme, as all sampled individuals have the same underlying distribution. We take the distribution from that reported in Fig. 2 in [9] for general offenders, which shows the relative proportions in each of ten crime categories of a random sample of general offenders who were sanctioned for an offense between 2007 and 2010.

-

3.

The third scheme uses a mixture of distributions, with 50 % of the population having the same proportions as scheme 2, 25 % having a tendency towards violence, and 25 % having a tendency towards property crime. This is a specialist scheme in the sense that certain offenders have a tendency to commit more violent offenders than average, and others have a tendency to commit more property crime than average. This form of specialization is sometimes known as lifestyle specialization [7, 8, 23].

It is worth noting that, for scheme 3, other models of specialization could easily be simulated. For example, another possible scenario is that offenders learn from prior experience, focusing on crimes they have already undertaken in the past. This experiential view of specialization is formally known as a “state dependence model” and would require that the probability distribution is continually changing as the number of crimes increases, based on prior history.

Tables 1 and 2 show the proportions used in the simulations for the ten category and three category crime groupings under each of the crime distribution schemes.

To carry out the simulations, we take 100,000 runs under each of the three schemes (equiprobable, marginal non-specialist, and specialist) for J=3 and J=10 crime categories, and for a range of values of N from 2 up to 500. For each simulated individual, the diversity index was calculated, and at the end of each simulation run, the average diversity index over all 100,000 simulated individuals was calculated. The simulations were run in R, and the simulation code is presented for the N=10 equiprobability case in the 1Appendix.

Results of the simulations

Tables 3 and 4 show the mean diversity indices for various values of N for ten and three crime categories.

Examining Table 3 first of all, we notice that under all three crime distribution schemes, the simulated mean diversity increases dramatically with the number of crimes, with the increase slowing when N is around 20. The value of D becomes nearly stable at N=500. Thus, when the crime distribution is held constant (and thus the degree of specialization is also fixed) the measuring tool of the diversity index increases with N. The true value of the diversity index under this fixed scheme is that obtained for large N and is well approximated by the value for D = 500, as there is little change in the simulated index at that point. There is therefore a bias in the measuring instrument D for small N- a true measure of diversity would not show any such relationship. We can also see another feature—the simulated mean diversity index is nearly identical for schemes 2 and 3—for the specialist crime distribution using mixtures of distributions and the non-specialist crime distribution using the proportions of crime observed in a real sample. One reason for this might be that the specialization scheme probabilities were chosen to average out to the probabilities in Scheme 2.

Turning our attention to the results for three crime categories (Table 4), we notice similar results. Again, the mean diversity index increases with N; quickly at first, then slowing as N gets close to 20. Near stability of D is again reached at N=500. The simulated values for the specialized crime distribution are again similar to the values for the non-specialized distribution. The mean diversities for three categories are in general lower than for ten crime categories (Table 3).

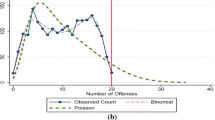

Figure 1 shows the results in graphical form (we do not show the results for the specialized Scheme 3 as they are nearly identical to the results for the unspecialized Scheme 2). It is easy to see that the simulated diversity indices increase dramatically and steeply up to about N=20, when the curves then start to flatten. The changes in index from N=2 up to N=500 are not a few percentage points, but encompass a large proportion of the diversity index’s range.

Both tables also present the percentage bias for each of the three schemes. This assumes that there is a true, “large sample” value of D, which we call D T , which would have been produced if we were able to observe a greater number of crimes from the underlying scheme. As the relationship between D and N for all schemes has flattened at N=500, we take the true value to be the simulated value of D at N=500. The percentage bias is calculated as

where % b i a s(N) is the estimated percentage bias, and D(N) is the value of D for a specific value of N. Examining the percentage bias for ten crime categories (J=10) and Scheme 1, we see that at N=20, the bias is under 5 %. For values of N less than 20, the bias increases dramatically, so that for N=10, the bias is around 10 %, and for N=5 it is just under 20 %. Surprisingly, for all other schemes and for both J=3 and J=10, the percentage bias is nearly identical.

These simulation results are highly concerning. The strong relationship between the simulated diversity index and N which has been observed in these tables (under conditions of unchanging levels of specialization) means that the diversity index can not be used to investigate the relationship between specialization and other criminological variables when the number of crimes is small and varies from person to person, or where the number of crimes vary over time. This means that the diversity index D will need adjusting in some way. The similarity in the percentage bias in each of the schemes and for both J = 3 and J = 10 however gives us a way forward. In other words, as the percentage bias appears to be invariant to the scheme and to the number of crimes, percentage bias could be used to adjust the diversity index. The next section describes how this might be done.

Correcting the Diversity Index

We provide two methods. The first is a general method which can be used to estimate D T , the true, large sample measure of diversity. The second is a method which is more appropriate for regression-based studies, where the interest is in correcting for the sample size in a regression context, while examining the effect of other criminological variable on specialization. We list each in turn.

The bias-correction method

The results of the simulations give estimates of the percentage bias, and these estimates of bias are nearly identical across differing schemes and different numbers of crime categories. For example, the estimated percentage bias for N=5 is −19.9 % for all three schemes for J=10, and either −19.9 or −19.8 % for the three schemes for J=3. We could therefore use this estimated percentage bias to correct the observed diversity indices. Equation 1 can be rewritten as

with D N representing the observed uncorrected diversity index, and D T representing the desired “corrected” diversity index value. We can use bias estimates from any of the three schemes and as the percentage bias estimates are nearly identical. Estimated percentage biases are not given for all values of N, in which case interpolation between the two nearest values of N can be used. The fraction \( \frac {100}{(100+\%bias(N))}\) is the multiplicative correction factor and is listed in Table 5 for scheme 2 and J=10. This starts from a value close to 2.00 for N=2 and declines quickly, tending to 1.00 as N approaches 500.

The regression-based approach

This method is appropriate for studies that seek to model D and corrects for N by including an independent variable of some function of N in the regression model. For example, [12] modeled D over a sample of offenders and corrected for frequency by including the average number of monthly offenses as an explanatory variable. However, our paper has shown that the relationship between the diversity index D and the number of offenses N is highly nonlinear (Fig. 1), and the method used by [12] will not fully account for this nonlinear relationship. If however it is possible to linearize the relationship between D and N, then such a relationship could be used in any regression study to allow for the dependence of the diversity index on N. We therefore looked for transformations which will linearise the highly nonlinear curves. This was not straightforward. We tried various transformations of both D and N (log and square root). For D, we also tried the logit transformation l o g i t(D) = l o g(D/(1−D), as the logit is a sensible transformation for variables constrained between zero and one. We also repeated this work using the adjusted diversity index \(D^{*} = \frac {J} {(J-1)}\times D \) rather than D—this seemed to us to be sensible as the adjusted diversity D ∗ covers the full range between 0 and 1 whereas D does not. We found that most transformations of D and N did not work, but one transformation showed promise. It was possible to nearly linearize the relationship between D and N under Scheme 1 when the logit of the adjusted diversity l o g i t(D ∗) was plotted against l o g(N), with no other combinations of transformations proving satisfactory. The transformed curves are linear and almost identical for J=3 and J=10. The relationship under Scheme 2 however was not perfectly linear, and still showed a small amount of curvature. Figure 2 shows the transformed curves. The reason for the curvature under Scheme 2 seems to be that the means of the simulated diversity indices reach an asymptote as N becomes large which is considerably smaller than the inverse of the correction factor of \(\frac {J}{(J-1)}\) used in Scheme 1. Thus, with N=500, the mean value of D under Scheme 2 for J=10 is 0.837 rather than 0.898.

Transformation of diversity index and offense frequency curves in Fig. 1 to approximate linearity

The nearly linear relationship between l o g i t(D ∗) and l o g(N) where the baseline category probabilities are equiprobable means that any regression which models the diversity index in terms of covariates can be corrected by the inclusion of an additional term of l o g(N), providing the logit of the adjusted diversity index is modeled, rather than the untransformed diversity index D. If baseline category probabilities are not equiprobable, then an additional term of l o g(N)2 should also be included. This latter term will account for the residual nonlinearity.

Our suggested recommendations for future empirical work using the diversity index are therefore:

-

1.

For most studies, including those where the interest is in whether specialization increases with frequency of offending N, we can use the bias correction method described above to correct observed diversity indices. This is our preferred methodology.

-

2.

For studies which seek to use a regression approach to examine the relationship between offense specialization and other criminological variables (such as age of onset, life course variables or age) and uses the diversity index to measure specialization, then any statistical regression should regress l o g i t(D ∗) against the covariates of interest, but including extra covariates of the log of the number of offenses l o g(N) and possibly the square of the log of the number of offenses (l o g(N))2. This will ensure that the relationship between the measuring instrument and D is controlled for.

An Empirical Example

We use the sample of 4090 general offenders used in [9] and examine their total offending history over their criminal career from age 10 up to the end of 2012. The sample is a random sample of general offenders in England and Wales who were sanctioned for an offense in the 4-year period 2007−2010. The sample includes all offenses which resulted in a sanction, whether this was a court conviction, or a caution, warning or reprimand. For each offender, we calculated their diversity index, and also the number of offenses contributing to that index. We then calculated the mean diversity for each value of N. We removed from the analysis the 1292 offenders with N equal to 1. Our aim in this example is to investigate the relationship between the diversity index and the number of offenses N for those offenders who had more than one offense.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the mean observed diversity index and the number of crimes in this sample, presented as a scatterplot. We see that the observed mean diversity index follows an increasing trajectory, slowing as N becomes large. We know, however, from our simulation work above, that much of the increase in the diversity index which we observe in the scatterplot is spurious and is due to the behavior of the diversity index when the number of crimes is small.

To correct for the bias in the measuring instrument, we consider in turn the two correction methods described in Section “Correcting the Diversity Index”. Our interest is in the relationship between specialization and N and so a regression of diversity on N would be appropriate. However, additional terms of l o g(N) and (l o g(N))2 would also be needed in the regression—there would then be three terms involving N: N, l o g(N), and (l o g(N))2 with the first term supposedly assessing true change of specialization with N, and latter two terms controlling for the measuring instrument. This is unlikely to be convincing as an analysis. We therefore adopt the first method outlined in Section “Correcting the Diversity Index” and correct the observed mean diversity index for each value of N by using the correction factors given in Table 5. By examining this corrected D, we can gain some insight into whether specialization is really related to the number or frequency of crimes.

Figure 4 shows the plot of the corrected diversity against N. We notice that there appears to be an small upward trend in this plot at low values of N. We test whether this is so, by fitting a weighted least squares (WLS) regression to this difference, regressed against N, and separately against l o g(N), and weighting by the number of offenders that contribute to each mean. The slope of the regression against N is positive but not significant, with β(s.e.)=0.000213(0.000202);p=0.293 ). The slope of the regression against l o g(N), however, is positive and significant, with β(s.e.)=0.0211(0.0090);p=0.0223). The l o g(N) model has an R-squared of 0.045 compared with an R-squared of 0.010 for the model with N as the independent variable, and we accept the l o g(N) model as the better model. The fitted trend line from this regression of corrected mean diversity against l o g(N) is superimposed in Fig. 4. This means that our data shows that real diversity increases with the number of crimes for small N, flattening off when N is large, and the increase is small but significant. The is therefore some evidence which supports the theoretical work of both Moffitt and Gottfredson & Hirschi.

Thus, if we correct the observed diversity index, we see a small increase of diversity with N; indicating that versatility appears to increase (and specialization appears to decrease) as N increases. The size of the effect is however small, and most of the increase in diversity which is evident from the uncorrected Fig. 3 is due to the bias in the measuring instrument.

Discussion and Conclusions

The diversity index provides an excellent method for examining changes in specialization over the lifecourse. However, this paper suggests that the use of the index is fraught with difficulty, as the index depends on the number of crimes that are used to calculate it. If the number of crimes increases during the lifecourse, then the diversity index will naturally increase, whether or not true diversity in offending has increased. We also found that the diversity index depends on the number of crime categories—the index seems to increase with J, although we have only looked at two values of J in this paper. The invariance of the diversity index with J is in fact another important issue, as this will allow the index to be compared across studies. More work needs to be carried out on this but it is not the focus of this paper.

There are two ways around the problem of the index depending on N. The first is to make sure that small numbers of crimes are not analysed. If small window widths (such as a month or a year) are used, then N is likely to be small. Larger window widths will ensure that N is larger and the problem then becomes less severe.

However, this is not the entire solution. A better way perhaps, and one suggested here, is to adjust the diversity index to correct for the relationship between the measuring instrument and N. This can be done in one of two ways as outlined in the results section. Either the regression method could be used, or the correction factor given in Table 5 can be applied.

The results given here are likely to affect the results of the [12, 22] and [15] papers to a degree, as control for N has not been carried out optimally. More specifically, the inclusion of N as a regression term to control for the relationship between diversity index and offense frequency will not correct for the bias in the measuring instrument. It is also worth mentioning that not only is control needed for the measuring instrument bias, but control may also be needed for the fact that real diversity may increase with N (a behavioral process).

Based on these results, we recommend that papers which have examined the criminological relationship between specialization and other criminological variables will need to be revisited. Using the corrected diversity index will be one way forward, but other methods of measuring diversity may prove equally useful. One promising method has been proposed by [24], which involves standardisation of the diversity index by N. However, if a new measure or method is proposed, then simulations will need to be carried out to ensure that there is no spurious relationship between any new proposed measure and the number of crimes.

References

Agresti, A., & Agresti, B. (1978). Statistical analysis of qualitative variation. Sociological Methodology, 9, 204–237.

Armstrong, T., & Britt, C. (2004). The effect of offender characteristics on offense specialisation and escalation. Justice Quarterly, 21(4), 843–876.

Brame, R., Paternoster, R., & Bushway, S. (2004). Criminal offending frequency and offense switching. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 20, 201–214.

Chaiken, J., & Chaiken, M. (1982). Varieties of criminal behavior Rand Corporation.

Deane, G., Armstrong, D., & Felson, R. (2005). An examination of offense specialization using marginal logit models. Criminology, 43(4), 955–988.

DeLisi, M., & Piquero, A. (2011). New frontiers in criminal careers research, 20002011: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39, 289–301.

Francis, B., Soothill, K., & Fligelstone, R. (2004). Identifying patterns and pathways of offending behaviour: a new approach to typologies of crime. European Journal of Criminology, 1, 48–87.

Francis, B., Liu, J., & Soothill, K. (2010). Criminal lifestyle specialization: female offending in England and Wales. International Criminal Justice Review, 20 (2), 188–204.

Francis, B., Humphreys, L., Kirby, S., & Soothill, K. (2013). Understanding criminal careers in organised crime: research report 74.

Gottfredson, M., & Hirshi, T. (1990). A General Theory of crime.

Mazerolle, P., Brame, R., Paternoster, R., Piquero, A.R., & Dean, C. (2000). Onset age, persistence, and offending versatility: comparisons across gender. Criminology, 38, 1143–1172.

McGloin, J., Sullivan, C., Piquero, A., & Pratt, T. (2007). Explaining qualitative change in offending: revisiting specisalisation in the short term. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 44, 321–346.

Moffitt, T. (1993). Life-course-persistent and adolescent limited antisocial behavior - a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Moffitt, T. (1994). Natural histories of delinquency. In Weitekamp, E, & Kerner, H (Eds.) Cross-National Longitudinal Research On Human Development and Crime and Childhood in the Inner City, Vol. 100. NL: Kluwer, Dordrecht.

Nieuwbeerta, P., Blokland, A., Piquero, A., & Sweeten, G. (2011). A life-course analysis of offense specialization across age: introducing a new method for studying individual specialization over the life course. Crime and Delinquency, 57 (1), 3–28.

Osgood, W., & Schreck, C. (2007). A new method for studying the extent, stability and predictors of individual specialisation in violence. Criminology, 45, 273–312.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Piquero, A., Mazerolle, P., & Dean, C. (1998). The forward specialization coefficient: distributional properties and subgroup differences. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 14, 133–154.

Piquero, A., Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Dean, C. (1999). Onset age and offense specialization. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36, 275–299.

Schreck, C. (2014). Offense specialization: key theories and methods. In Bruinsma, G, & Weisburd, D (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 3315–3321). New York: Springer.

Simpson, E. (1949). Measurement of diversity. Nature, 163, 688–688.

Stander, J., Farrington, D., Hill, G., & Altham, P. (1989). Markov chain analysis and specialization in criminal careers. British Journal of Criminology, 29, 317–335.

Sullivan, C., McGloin, J., Pratt, T., & Piquero, A. (2006). Rethinking the norm? of offender generality: investigating specialization in the short-term. Criminology, 44, 199–233.

Sullivan, C., McGloin, J., Pratt, T., & Piquero, A. (2009). Detecting specialization in offending: comparing analytic approaches. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 419–441.

Sweeten, G., & Blokland, A. (2015). Evidence for life-course offense specialization from group-based multi-trajectory models (unpublished).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (award numbers ES/K006460/1. The empirical part of this study was a reanalysis of official UK Police data which is not publicly available. We are grateful to referees whose comments and insight have added to this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Appendix:

Appendix:

The R code for simulating values of the diversity index under Scheme 2 is presented below. It can be adapted for different probability specifications and different numbers of crime categories. The code can be downloaded from 10.17635/lancaster/researchdata/85 .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Francis, B., Humphreys, L. Investigating the Relationship Between the Diversity Index and Frequency of Offending. J Dev Life Course Criminology 2, 397–416 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0034-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0034-5