Abstract

Full-scale roller rigs are recognized as useful test stands to investigate wheel-rail contact/damage issues and for developing new solutions to extend the life and improve the behaviour of railway systems. The replacement of the real track by a pair of rollers on the roller rig causes, however, inherent differences between wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact. In order to ensure efficient utilization of the roller rigs and correct interpretation of the test results with respect to the field wheel-rail scenarios, the differences and the corresponding causes must be understood a priori. The aim of this paper is to derive the differences between these two contact cases from a mathematical point of view and to find the influence factors of the differences with the final aim of better translating the results of tests performed on a roller rig to the field case.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The contact between wheel and rail is one of the most important features of the railway system, and this contact pair has attracted great attention since the beginning of railway engineering. Unfortunately, the problems involved in the wheel-rail contact interface have not been completely solved due to the complexity of the problem. Many attempts have been made from both theoretical and experimental points of view. Moreover, field experiments on wheel-rail contact mechanics and dynamics are often challenging due to the difficulties in adequately controlling the test conditions [1]. Roller rigs are a good alternative in this case, thanks to their high controllability and flexibility, and have been used as experimental tools in railway application over a long time. A variety of roller rig designs have been introduced, targeting different research aims, more detail on this topic can be found in [2–4]. A. Jaschinski et al. [2] performed a comprehensive survey for both full-scale and scaled model roller rigs on the application to railway vehicle dynamics. Zhang et al. [4] reviewed the development history of the roller rig for railway application and performed a detailed comparison between rollers and track in terms of geometry relationship with wheel, creep coefficient, stability, vibration response and curve simulation. Allen [5] and Yan [6] documented in detail on the errors caused by scaled roller rigs for the study of the dynamic behaviour of railway bogies. Keylin et al. [1] derived explicit analytical expressions for comparing contact patch dimensions and Kalker’s coefficients for a wheel moving on a roller and on a tangent track, based on Hertz and Kalker’s linear theory. Taheri et al. [7] compared the contact patch formed by a single wheelset when coupled to a roller and to a tangent track under the assumptions of the Hertz’s theory. Zeng [8] compared the geometry contact characteristics of the wheel-rail and that of the wheel-roller based on a three-dimensional contact searching method.

Nevertheless, a systematic analysis of wheel-roller contact and the differences with respect to the wheel-rail case are missing in the literature. It should be noted that the roller rig test will never completely replace the field test due to inherent differences caused by the replacement of the rail by rollers in a roller rig system. Therefore, it is very important to know the differences between these two systems and the corresponding reasons in order to efficiently perform wheel-rail contact study on a roller rig and to correctly interpret the test results and to compensate for deviations between the roller rig and a real track. This analysis should cover in particular

-

the geometry of wheel-rail/wheel-roller contact;

-

differences in the formation of the contact patch;

-

factors affecting the creepages in a test performed on a roller and their effect on tangential contact forces.

The aim of this paper is to provide a thorough examination of the differences between these two contact cases from a mathematical point of view and to find the influence factors of the differences for better translating the test results on the roller rig to the field test. To this aim, a new approach for solving the normal contact problem for the wheel-roller couple is proposed, and the expressions of the creepages and spin are obtained for the wheel-roller couple. The results of this new approach are presented comparing the case of the wheelset running on a standard track and on rollers, and the differences between these two cases are discussed in the light of their effects on surface damage and degradation occurring in the wheels and the rails.

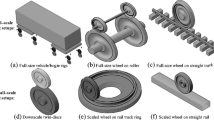

2 Full-Scale Roller Rigs for Tests on a Single Wheelset

Among all of the roller rigs existing in laboratory, the full-scale roller rig for a single wheelset test is one of most similar systems to a real wheelset-track system from both dynamics and contact mechanics points of view. The mechanical layout for a roller rig of this type is shown in Fig. 1. It consists of a roller with two wheels driven by a motor. A full-scale wheelset is mounted on the top of two rollers with real rail profiles and connected through primary suspensions to a transversal beam representing one half of the bogie frame. Compared with the roller rig for test on a complete vehicle, the high controllability and flexibility of the single wheelset roller rig make it possible to obtain adequate data on the dynamics of the system and on wheel-rail contact under various conditions which are essential for investigating the adhesion and creep of the wheel over the rail. This configuration of the roller rig allows to perform studies of wheel-rail interaction and also tests concerning the dynamic behaviour of a wheelset/bogie, see [9, 10]. However, this paper only concentrates on wheel-rail contact.

3 Contact Formulation for Wheel-Rail and Wheel-Roller Systems

From a mathematical point of view, the contact problem can be solved for both wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact according to the following four steps [11, 12]. The first step is to solve the geometrical problem, in which the locations of the contact points on the contacting bodies are determined. This is followed by solving the normal contact problem, in which the shape and size of the contact patch formed in the contact interface due to body deformation and the corresponding pressure distribution over the contact patch are determined. The third step is to deal with the kinematic problem, in which normalized kinematic quantities, the so-called creepages, are determined. These quantities measure the relative velocities between the contacting bodies at the contact points. In the final step, the tangential problem is solved; this concerns the prediction of tangential stresses at the contact interface which is generated by friction and creepages within the contact zone [11, 13, 14]. All these steps need to be dealt with differently for the case of wheel-roller contact compared to the wheel-rail case, as described in the next section.

3.1 Geometrical Problem

The contact geometry analysis deals with the contact point searching problem between the contacting bodies, i.e. wheel-rail and wheel-roller pairs in this case. The location of contact depends on the dynamic conditions as well as material properties of the contact pair if body deformation is considered. There are many approaches for the detection of the contact points for wheel-rail contact as documented in [11]. Most of the approaches available in the literature assume that the yaw angle of the wheelset against the track is very small and negligible when solving the geometric contact problem so as to form the so-called bi-dimensional methods [14]. This assumption largely simplifies the calculation, leading to fast solutions that can be implemented in rail vehicle online dynamics simulation. However, the replacement of the rail by a roller makes the geometric contact problem more complicated, and the traditional bi-dimensional methods may not be applicable any longer due to the considerable yaw influence on the contact location in the case of the wheel-roller contact. To deal with this problem, a three-dimensional model is needed. Some existing approaches for wheel-roller geometry contact analysis can be found in [4, 8, 15].

It is clear that the geometric contact condition between the wheel and rail/roller is the same for zero yaw angle conditions assuming the contacting bodies to be rigid. The comparisons on the geometry contact relationship between the wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact pairs are available in the literature, for instance [4, 8, 12]. Therefore, no further discussion is needed here, but one typical case study is shown in Fig. 2 for the completeness of this study. The calculation conditions are as follows: profile combination is new S1002/UIC60 with 1:20 rail inclination, the radius of the roller is 1 m and the yaw angle of the wheelset is 60 mrad.

It is interesting to note in Fig. 2 that two-point contact occurs when the wheelset is shifted by 5 mm approximately in lateral direction for wheel-rail contact, but this value is slightly different on the roller rig due to the curvature of the rollers. Obviously, the differences can be decreased by increasing the radius of the roller, but the dimension of the roller is limited in practice considering the increased cost and difficulties related with the manufacturing and installation of the rig. It should be also noted that 60 mrad is a quite large yaw angle for the wheelset and that smaller differences are found for smaller yaw angles.

3.2 Normal Problem

The well-known Hertzian theory [16] is widely used for solving the normal contact problem in rail vehicle dynamics simulation for its simplicity and calculation efficiency. However, Hertzian theory is valid based on half-space assumption and elliptic contact condition. In order to obtain more realistic contact information for the purpose of comparison between wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact (especially in terms of shape and size of the contact patch and of pressure distribution), the use of a more advanced contact model is required. The most elaborate contact model to date can be established by finite element method [17, 18] which is quite complicated and time consuming. The same problem can be dealt with using the boundary element method as done, e.g. by Prof. Kalker’s algorithm CONTACT [19] and by the model proposed by Knothe and Le The in [20]. The so-called approximate contact methods represent a trade-off between efficiency and accuracy in the solution of the normal problem and therefore are generally considered as best suited for both local contact analysis and for online dynamics simulation. Well-known approximate models include the Kik–Piotrowski model based on virtual penetration concept [21–23], the STRIPES model proposed by Ayasse and Chollet [24] and Linder’s model [25]. Some interesting surveys of the existing approximate methods and the comparison and analysis among them can be found in [22, 26].

The Kik–Piotrowski model has been chosen as the basis for this study. Some modifications have been introduced to extend the original method to deal with both wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact conditions. The Kik–Piotrowski model is a fast and non-iterative method to calculate normal contact problem. An outline of this method will be given in this section, for more details the reader is referred to [21–23]. The idea of this method is presented in Fig. 3. When the undeformed surfaces of wheel and rail/roller, touching in the geometrical point of contact O which is determined from geometric contact analysis, are shifted towards each other by a distance δ, called the penetration, they penetrate and intersect on a closed line, whose projection on the x-y plane is called the interpenetration region. On the basis of some similarity of shapes of the contact zone and interpenetration region, the contact zone is determined by scaling the interpenetration depth δ o = ϵδ with an approach scaling factor of ϵ = 0.55 and the resulting interpenetration region is taken as the real contact zone.

Contact zone determined with virtual interpenetration method, adapted from [21]

In order to solve the problem numerically, a coordinate system Oxyz representing the contact reference system is defined firstly with the x-axis pointing along the rolling direction of the wheelset, and the y-axis parallel to the wheel axle. The undeformed surface with the same x, y coordinates in contact reference system is assumed as

where subscript yz stands for the function defined in y−z plane and R w and R r are the principal radii of the wheel and rail/roller, respectively, at the geometrical point of contact in rolling direction. For wheel tread and rail top contact R r goes to infinite, while this is not the case for the wheel-roller contact case. The separation of profiles f yz (y) = z w yz (y) + z r yz (y) is obtained from the sum of the cross-sections z w yz (y) of the wheel rolling surface and z r yz (y) of the rail surface by x = 0 in the contact plane. To proceed with the presentation of the method, the interpenetration function of the profiles is defined in the contact plane as

where δ 0 is the virtual interpenetration. The width of the contact patch can be determined by solving Eq. (2). It should be mentioned that the contact shape can be corrected by adjusting the interpenetration function, cf. [22, 23], but no shape correction is applied in this study for simplicity.

The contact zone is determined by the x coordinates of its leading and trailing edges described by formula (3) in the original method based on the assumption that the wheel-rail contact problem is stated in terms of two bodies of revolution with their axes laying in the same plane. The same assumption was made by Linder [25].

where subscript xz means that the function is defined in the x-z plane and superscripts l and t indicate the terms associated with the leading and trailing edges of the contact patch, respectively.

In order to determine the contact boundary for wheel-roller contact, the following modifications of Eq. (3) are proposed. Firstly, the contact patch is partitioned into strips paralleling with the x-axis towards to the rolling direction of the wheel. Hence, the profile functions are converted to discrete forms by strips y i (i = 1…n). Then, the extremities of each strip can be determined by solving Eq. (4) instead of Eq. (3). The two solutions of Eq. (4) for each strip correspond to the coordinates of the leading and trailing edges of that strip. All the coordinates comprise the boundary of the contact zone.

where g yz (y i ) is the interpenetration function at the i-th strip in contact patch, z w xz (x,y i ) and z r xz (x,y i ) are the rolling circle of the wheel and roller with the radius of R cw(y i ) and S cr(y i ), respectively, over the i-th strip, which are expressed by Eqs. (5) and (6).

where x ∈ [−R cw(y i ), R cw(y i )] is the longitudinal coordinate of the rolling circle in the contact plane. It should be noted that S cr(y i ) is a straight line in the case of tangent track.

Moreover, it is assumed that the normal pressure is semi-elliptical in the direction of rolling and has the following expression:

Following the same procedure documented in Ref. [21], the normal contact problem can be solved numerically for both wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact system.

It should be pointed out that the influence of the wheelset’s yaw angle on the normal contact solution is essential for wheel-roller contact and can be included based on the similar idea proposed here, but it will not be discussed further in the current paper for simplicity.

3.3 Kinematical Problem

With reference to Fig. 1, it can be seen that the wheelset on the roller rig has the same degrees of freedom as on a track, except the constraint in longitudinal direction. Furthermore, the two rollers fixed on the same axle can only rotate around its axle. To accomplish the kinematic analysis of a wheelset on a pair of rollers, a convenient set of reference frames should be introduced as shown in Fig. 4. The wheelset reference frame is denoted by O w X w Y w Z w attached to the wheelset’s centre of mass so that axis O w Y w coincides with the wheelset’s axis of rotation, the O w Z w axis points upwards and the O w X w axis completes the right-handed coordinate system. Similarly, a roller reference frame is introduced and denoted by O ro X ro Y ro Z ro attached to the roller’s centre of mass which is defined as the inertial frame. Two contact reference frames O cl X cl Y cl Z cl and O cr X cr Y cr Z cr are introduced at the contact interfaces between the left-hand and right-hand wheels of the wheelset and rollers at the wheelset central position.

It is assumed that the wheelset reference frame O w X w Y w Z w is obtained from the inertial frame by performing two successive rotations. The axes of the reference frames are parallel before rotation, and the first rotation is made about the z-axis by an angle ψ called yaw angle (positive in counter-clockwise direction) followed by a second rotation about the x-axis by an angle φ called roll angle. Therefore, the transformation matrix A w2i connecting the wheelset frame to the inertial frame is expressed as follows:

Since the angles of rotation are generally small in railway dynamics, the small angle approximation can be applied, so that the transformation matrix reduces to

The position vectors of the contact points on the wheel and roller can be defined in the inertial frame as follows:

where the position vector of the origin of the wheelset reference frame in the inertial frame is expressed as

and the position vectors of the contact points in the wheelset reference frame can be expressed in the following forms: for the left-hand wheel

and for the right-hand wheel

where r i (i = l,r) represents the radius of the left-hand and right-hand wheels, respectively, l is the half distance between the contact points on the left-hand and right-hand wheels and β is the shift angle of the contact point on the roller with respect to the vertical plane of the inertial frame caused by a non-zero yaw angle ψ. It is assumed that this angle is the same for the left-hand and right-hand side on the roller and can be approximated by Eq. (14), since it is very small in ordinary circumstances.

In Eq. (14), r 0 and s 0 denote the radii of the wheel and roller at the central position, respectively.

Taking the derivative of Eq. (11), the velocity vector of the contact point located on the wheel with respect to the inertial frame is obtained as

where \( {u_{{{\text{w}}i}}} = {A^{{{\text{w}}2i}}} {\bar{u}_{{{\text{w}}i}}} \) is the position vector of the point of contact on the wheel defined in the inertial frame which is determined from Eqs. (9), (12) and (13) for the left-hand and right-hand wheels, respectively, as follows:

and

and ω w is the absolute angular velocity vector at the point of contact defined in the inertial system as

with Ωw = V/r 0 the rolling angular velocity of the wheelset.

Substituting Eqs. (11), (17) and (18) into Eq. (15), the velocity vectors of the contact point on the wheelset in the inertial frame are obtained as follows. For the left-hand wheel:

and for the right-hand wheel:

Similarly, the velocity vector of the contact point on the roller in the inertial frame can be expressed as

where ω ro is the angular velocity of the roller with the following form:

and u roi stands for the position vector of the contact point in the inertial frame. For the left-hand roller, the expression of this vector is

and for the right-hand roller the expression is

Hence, the velocity vector of the point of contact is obtained. For the left-hand roller,

and for the right-hand roller:

Thus, the velocity differences between the wheel and roller at each point of contact in the inertial frame can be calculated as follows. For the left side

for the right side:

and the difference of angular velocity is

To determine the creepages and spin, the velocity differences obtained above must be resolved in the contact plane where they are defined. It is assumed that the contact frames are connected to the wheelset frame by the following transformation matrices for the left and right wheels, respectively.

and

where δ i (i = l,r) denotes the contact angle.

Hence, the transformation matrices connecting the inertial frame to the contact frame can be obtained for the left and right side wheels by the following operation. For the left side

and for the right side:

Therefore, the velocity differences between the wheel and roller in the contact plane are obtained as

Now, the creepages can be obtained by definition as follows. The longitudinal creepages on the left and right wheels are

the lateral creepages are

and the spin creepages are

It can be seen from the expressions above that the radius of the roller and the shift angle (function of yaw) contribute to the differences in terms of creepages and spin with respect to wheel-rail contact condition. The corresponding expressions for wheel-rail contact condition can be obtained by setting s 0 = ∞ and β = 0. Moreover, the longitudinal and lateral creepages can be simplified further by assuming that the contacting bodies remain in contact at all times which means the z components vanish in the expressions (35) and (36).

3.4 Tangential Problem

The common method to solve the wheel-rail tangential contact problem is represented by the FASTSIM algorithm [13], also due to Kalker. This method was originally developed for elliptic contact condition, but can be extended to cover a more general geometry of the contact patch. The difficulty is to determine the flexibility parameter that is required by this method. To overcome this, Kik and Piotrowski proposed a method to define an equivalent ellipse for each separate contact zone by setting the ellipse area equal to the non-elliptic contact area and the ellipse semi-axes ratio equal to length to width ratio of the patch. The flexibility parameter is determined by equating the two solutions obtained from the linear complete theory and from the simplified theory for elliptical contact area and pure longitudinal, lateral and spin creepages. In addition, there are two options with respect to the choice of the flexibility parameter, namely considering one single weighted mean flexibility parameter or three flexibility parameters one for each creepage component. According to [27], the single flexibility parameter will reduce the agreement of FASTSIM to the exact theory. Therefore, three flexibility parameters are used in the current study.

From the main assumption of the linear theory which neglects slip in the contact zone, the tangential stress distribution is derived in the form:

where ξ i (i = 1 − 3) are the longitudinal, lateral and spin creepages, and L i (i = 1 − 3) denotes the flexibility parameter for each creepage component.

The stresses stated in Eq. (38) cannot exceed the so-called traction bound. Slip occurs in the region where the tangential stresses predicted by Eq. (38) are greater than the traction bound. The formulation for the traction bound used in this paper is obtained by applying Coulomb’s friction law locally with a constant friction coefficient, i.e. μp(x i ,y j ). The tangential forces are obtained from the numerical integration of the stresses over the contact patch.

4 Results and Discussions

The effects of roller rig testing in the experimental investigation of wheel-rail contact have been addressed in Sect. 3 under four different points of view. In reality, all of these factors interact with one another, thereby it is essential to investigate their combined influence on the contact solution. To this end, a set of cases with various contact positions and radii of roller have been chosen to quantify the influence. The calculation parameters listed in Table 1 are used throughout the simulations.

For simplicity, the track irregularities are neglected and no wheelset velocity component is considered except in the rolling direction. The creepages are calculated according to expressions (35)–(37) as presented in Table 2. According to Eq. (35), the last three terms represent the additional contribution of the roller rig to the longitudinal creepage with respect to wheel-rail contact case. It is clear that the major difference in the longitudinal creepage is caused by the variation of the roller head circumferential velocity across its profile. The lateral creepage is zero when the yaw angle is assumed to be zero based on Eq. (36) under the considered contact condition. It can be seen from Eq. (37) that the additional contribution of the roller rig to the spin creepage is coming from the last three terms in the expression that represents, respectively, the effect of the wheelset yaw angle and of the angular velocity of the roller. These additional terms explain the remarkable increase of the spin for the roller rig case which is shown in Table 2. The contact estimation results are presented in two groups for normal contact solution and tangential contact solution, respectively.

4.1 Normal Contact Solution

The solutions of the normal contact problem in terms of the shape and area of the contact patch and the corresponding pressure distribution within the contact region are obtained by the method proposed in Sect. 3.2 for wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact conditions, respectively. The calculation results for the case studies listed in Table 2 are presented in Fig. 5, and the results of wheel-rail contact and of wheel-roller contact obtained at the same contact position are presented in the same figure for comparison.

It can be seen from Fig. 5 that these two simulation cases correspond to a highly non-elliptic contact condition in the first case and nearly elliptic contact condition in the second case. In Fig. 5a, b, it is observed that the length of the contact patch in longitudinal direction decreases for the roller rig with respect to the rail due to the finite radius of roller, this effect being more visible for the smaller value of the roller radius. On the contrary, the width of the contact patch is slightly increased in the case of wheel-roller contact. The maximum contact pressure over the contact zone is increased by a decrease of the roller radius as the same load is spread across a smaller contact area, see Fig. 5c, d. The change of the contact patch also affects the semi-axis ratio and consequently affects the creep coefficient and the creep forces. The differences caused by the roller rig in terms of contact area and maximum contact pressure should be taken into account when the roller rig is used for contact deterioration mechanism studies such as wear and rolling contact fatigue. To quantify the difference involved in the normal contact solution, a statistical summary of the results is presented in Table 3.

It can be concluded from Table 3 that the differences are increasing with the decrease of radius of the roller and the agreement between wheel-roller and wheel-rail contact is better for the approximately elliptic contact condition, i.e. case 2. It should be mentioned that the results reported here are dependent on the particular parameters assumed in this study, but the analysis approach and the conclusions are generally applicable to any roller rig of this kind.

4.2 Tangential Contact Solution

The corresponding tangential contact solutions for the cases introduced in Sect. 4.1 are presented in Fig. 6 in terms of the stress distribution and division of the contact patch into a stick region and a slip region.

Stress distribution over the contact patch formed by wheel-rail (top), wheel-roller with a radius of 1 m (middle) and wheel-roller with a radius of 0.5 m (bottom) for cases 1 (left column) and 2 (right column). Black and red arrows represent the stress vector in the stick and slip regions, respectively

It can be observed from Fig. 6 that the pattern of the stress distribution over the contact patch is similar for wheel-rail and wheel-roller contact conditions in both cases considered. However, the relative percentage of the slip region over the whole contact area is slightly larger in the case of wheel-roller contact. The resultant tangential creep forces in longitudinal and lateral directions are calculated by integration over the contact area, and are presented in Table 4 together with the differences caused by the roller rig test.

It can be seen from Table 4 that the resultant longitudinal force produced on the roller rig differs significantly from the same quantity in the wheel-rail contact case when the contact patch is highly non-elliptic, i.e. for y = 0 mm, and the difference increases as the radius of roller decreases, whereas the differences are relative small for approximately elliptic contact condition, i.e. for y = 3 mm, especially when the lateral component of the tangential force is concerned.

To evaluate the contact surface damage situation the frictional power at the contact patch is calculated for each case study, and the results are summarized in Table 5.

It is clear from Table 5 that the frictional power increases considerably in the case of wheel-roller contact with respect to wheel-rail contact under the same condition, and the differences are particularly relevant for a smaller radius of the roller. It should be noted that the increase of frictional power implies an accelerated manifestation of wear and fatigue effects in the contact pair. This accelerated effect caused by the roller should be taken in proper account by wheel-rail surface damage/deterioration studies performed using roller rigs. It is worth mentioning that this accelerated effect is desirable for wheel material comparison/optimization concerning wear, because the roller rig is capable of reproducing wear patterns within a much shorter time compared to field testing. The test results from the roller rig can be used to examine and document differences in hardening, profile development, polygonalization and possible crack formation of the wheel under test [28]. More details on the wear test on the roller rig can be found in references [28, 29].

5 Conclusions

This paper investigated the differences between wheel-rail contact and wheel-roller contact, with the final aim of assessing the extent to which the results obtained on a roller rig can be extended to the case of a wheelset running on a real track.

A systematic description and comparison on the methodology for solving the contact problem at the wheel-rail and wheel-roller interfaces have been done in terms of the geometric contact problem, normal contact problem, kinematic problem and tangential contact problem. A modified Kik–Piotrowski model has been proposed to deal with the wheel-roller contact problem for zero yaw angle contact conditions.

Simulation results have pointed out the differences implied by a test performed on a roller rig compared to wheel-rail contact in terms of size and shape of the contact patch and distribution of the normal and tangential stresses. This analysis provides a useful framework for interpreting the results of tests performed on a roller rig, e.g. wear and/or rolling contact fatigue tests and for extending the results to the real behaviour of the wheelset in the field. The accelerated effect on wheel surface deterioration during the test on the roller rig is preferable for material optimization study, while it is not the case for reproducing the wear process of the wheel in service. In this second case, the above-mentioned effect must be taken into account when translating the results of the test to the field case.

Further work will focus on the development of a contact model which is capable of taking into account the influence of yaw angle for both normal and tangential problems.

References

Keylin A, Ahmadian M (2012) Wheel-rail contact characteristics on a tangent track vs a roller rig. In: Proceedings of the ASME 2012 rail transportation division fall technical conference, Omaha

Jaschinski A, Chollet H, Iwnicki S, Wickens AH, Würzen JV (1999) The application of the roller rigs to railway vehicle dynamics. Veh Syst Dyn 31:345–392

Meymand SZ, Craft MJ, Ahmadian M (2013) On the application of roller rigs for studying rail vehicle systems. In: Proceedings of the ASME 2013 rail transportation division fall technical conference, Altoona

Zhang W, Dai H, Shen Z, Zeng J (2006) Roller rigs. In: Iwnicki S (ed) Handbook of railway vehicle dynamics. Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, pp 458–504

Allen PD (2006) Scaling testing. In: Iwnicki S (ed) Handbook of railway vehicle dynamics. Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, pp 507–525

Yan M (1993) A study of the inherent errors in a roller rig model of railway vehicle dynamic behaviour. ME thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University

Taheri M, Ahmadian M (2012) Contact patch comparison between a roller rig and tangent track for a single wheelset. In: Proceedings of the 2012 joint rail conference, Philadelphia

Zeng Y, Shu X, Wang C, Yu W (2013) Study on three-dimensional wheel/rail contact geometry using generalized projection contour method. In: Zhang W (ed) proceedings of the IAVSD 2013 international symposium on dynamics of vehicles on roads and tracks, Qingdao

Bruni S, Cheli F, Resta F (2001) A model of an actively controlled roller rig for tests on full size wheelsets. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part F: J Rail Rapid Transit 215:277–288

Liu B, Bruni S (2015) A method for testing railway wheel sets on a full-scale roller rig. Veh Syst Dyn 53(9):1331–1348

Shabana AA, Zaazaa KE, Sugiyama H (2007) Railroad vehicle dynamics: a computational approach. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC, Boca Raton

Bosso N, Spiryagin M, Gugliotta A, Somá A (2013) Mechatronic modeling of real-time wheel-rail contact. Springer, London

Kalker JJ (1982) A fast algorithm for the simplified theory of rolling contact. Veh Syst Dyn 11:1–13

PomboJ Ambrósio J, Silva M (2007) A new wheel-rail contact model for railway dynamics. Veh Syst Dyn 45(2):165–189

Yang G (1993) Dynamic analysis of railway wheelsets and complete vehicle systems. Doctoral dissertation, Delft University of technology, Delft

Hertz H (1882) Über die berührung fester elastische körper. J Für Die Reine U Angew Math 92:156–171

Damme S, Nackenhorst U, Wetzel A, Zastrau B (2002) On the numerical analysis of the wheel-rail system in rolling contact. In: Popp S (ed): system dynamics and long-term behaviour of railway vehicles, track and subgrade. Lecture Notes in applied mechanics, vol 6, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 155–174

Vo KD, Zhu HT, Tieu AK, Kosasih PB (2015) FE method to predict damage formation on curved track for various worn status of wheel/rail profiles. Wear V322–323:61–75

Kalker JJ (1990) Three-dimensional elastic bodies in rolling contact. Solid mechanics and its applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Knothe K, Le The H (1984) A contribution to calculation of contact stress distribution between elastic bodies of revolution with non-elliptical contact area. Comput Struct 18(6):1025–1033

Kik W, Piotrowski J (1996) A fast, approximate method to calculate normal load at contact between wheel and rail and creep forces during rolling. In: Zobory I (ed.), proceedings of 2nd mini-conference on contact mechanics and wear of rail/wheel systems, Budapest

Piotrowski J, Chollet H (2005) Wheel–rail contact models for vehicle system dynamics including multi-point contact. Veh Syst Dyn 43(6–7):455–483

Piotrowski J, Kik W (2008) A simplified model of wheel/rail contact mechanics for non-Hertzian problems and its application in rail vehicle dynamic simulations. Veh Syst Dyn 46(2):27–48

Ayasse J, Chollet H (2005) Determination of the wheel rail contact patch in semi-Hertzian conditions. Veh Syst Dyn 43:161–172

Linder Ch (1997) Verschleiss von Eisenbahnrädern mit Unrundheiten. Diss. Techn. Wiss. ETH Zürich, Nr. 12342

Sichani MS, Enblom R, Berg M (2014) Comparison of non-elliptic contact models: towards fast and accurate modelling of wheel–rail contact. Wear 314:111–117

Vollebregt EAH, Wilders P (2011) FASTSIM2: a second-order accurate frictional rolling contact algorithm. Comput Mech 47:105–116

Ullrich D, Luke M (2001) Simulating rolling-contact fatigue and wear on a wheel/rail simulation test rig. World Congress on Railway Research, Cologne

Braghin F, Bruni S, Resta F (2001) Wear of railway wheel profiles: a comparison between experimental results and a mathematical model. In: Ture H (ed.), 17th international symposium on dynamics of vehicles on roads and tracks, pp 478–489

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editor: Xuesong Zhou

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Bruni, S. Analysis of Wheel-Roller Contact and Comparison with the Wheel-Rail Case. Urban Rail Transit 1, 215–226 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40864-015-0028-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40864-015-0028-3