Abstract

National assessments produced regularly from 1996/97 to 2019/20 provide standard estimates of the evolution of poverty in Mozambique. Stylised facts point to significant reduction in monetary and multidimensional poverty until 2014/15, even though characterised by persistent urban–rural and regional inequalities in several dimensions, followed by worsening deprivation during 2014/15–2019/20. In this paper, we rely on first-order dominance (FOD) methodology to check the robustness of standard poverty estimates while providing deeper insights into what happened in this poverty-stricken country. Our main findings include that the capital city, Maputo, and surrounding areas progressively came to dominate all other provinces in terms of well-being, and the provincial rankings from spatial FOD analysis are very stable over time. Rural areas, mainly those in the northern and central regions, are, with a few exceptions, always at the bottom of the ranking. Moreover, our FOD temporal analysis reveals that 2019/20 dominates, with a high degree of confidence, the results from earlier years, pointing to positive development over time, but with one important exception. The comparison between 2019/20 and 2014/15 is indeterminate, indicating that no significant advancement took place during this period. What stands out is the compelling need for concerted policy action to address the strong and persistent spatial gaps in welfare and poverty, including the capacity to respond effectively to external and internal shocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and context

The Government of Mozambique (GoM) emphasises in its 2020–24 five-year plan and in its 2025–44 national development strategy the need to improve welfare and living standards for its people, reducing at the same time social inequalities and poverty, and creating an environment of peace, harmony, and safety (GdM 2020; 2024). For evidence-based policy-making in pursuit of these goals, the availability of detailed household data and in-depth analyses of the current state of the country are of utmost importance. The national poverty assessments (DNPO 1998, 2004; DNEAP 2010; DEEF 2016; DNPED forthcoming) are key building blocks in this effort, providing estimates of the evolution of consumption and multidimensional poverty from 1996/97 to 2019/20.

The first household budget survey, undertaken in 1996/97, portrayed a country in distress as a consequence of the recently ended armed conflict, which lasted about 17 years and was only concluded by the Rome General Peace Agreement in 1992. Monetary poverty was overwhelming, and most families did not have access to education, safe water sources, quality sanitation, electricity, and quality housing, among other facilities. In the following years, the country registered rapid gains between 1996/97 and 2002/03, both in the monetary and non-monetary dimensions. The pace of poverty reduction slowed between 2002/03 and 2008/09 (DEEF 2016), mainly due to global price shocks in the period 2007–09 (Arndt et al. 2008, 2016b). Subsequently, gains reasserted themselves between 2008/09 and 2014/15 so that the national poverty assessment published in 2016 provided an optimistic view regarding possible future developments. Indeed, substantial improvements in monetary and non-monetary terms were registered in both rural and urban zones and in every province, relative to 1996/97 (DEEF 2016).

Nonetheless, the country faced an unprecedented series of shocks between 2014/15 and 2019/20, which led many households to again fall into (monetary) poverty. The poverty rate, as shown in the following section, increased from about 46% to about 68%. From the point of view of alternative dimensions of poverty, such as housing and access to services and goods, the gains observed in previous years effectively halted, leaving Mozambique as one of the poorest countries in the world in both monetary and multidimensional poverty perspectives (World Bank 2023b; Egger, Salvucci, and Tarp 2023a, b). The series of shocks, analysed in more detail later in the paper, included: a debt crisis; major climatic shocks; an armed conflict in the northern region; and a pandemic (Mahdi et al. 2018, 2019; World Bank 2018, 2020, 2023b; Egger et al. 2023; Salvucci and Tarp 2023a, b; DNPED forthcoming).

Each of these recent shocks, plus long-term structural characteristics of deprivation distribution in Mozambique, shaped the spatial and temporal poverty trends we observe today. A map with provinces and main cities in Mozambique is presented in Fig. 1 to facilitate comprehension of the evolution of the deprivation trends and geographical divisions.

With respect to long-term structural characteristics, persistent urban–rural and regional inequalities in several dimensions exist, that have been highlighted in all the poverty assessments produced after 1996/97. These are rooted in a complex set of interacting elements. They include the way Portugal administered the colony from the sixteenth century, which initially consisted of controlling valuable trade, particularly gold and ivory, from a few coastal settlements; in the development of the slave trade and of private concessions in vast areas of the interior; and in the administrative model that developed in the twentieth century when the Portuguese established a more comprehensive administration for the entire country, and moved the capital from the northern Mozambique Island to the southern city of Maputo (previously Lourenço Marques) (Rodrigues 2019). This marked a shift of relevance and economic interests from the north to the south of the country, which was better linked to and economically interconnected with its fast-developing neighbour, South Africa. So, some coastal, mainly urban areas throughout the country maintained their relevance even after the shifting of the capital and main economic interests from the north to the south, especially if—like the areas of Beira, Quelimane or Nampula-Nacala—they were connected through ‘corridors’ to landlocked countries in the interior (e.g. Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia). The increasingly urbanised southern region registered more rapid gains until recent years.Footnote 1

In particular, national poverty assessments up to 2019/20 pointed out that living conditions in the south, especially in its urban areas, were already considerably better in 1996/97. This was the case across almost all welfare dimensions and all methods applied, with strikingly high disparities with regard to access to safe water sources, quality sanitation, electricity, quality housing, and ownership of durable goods. Moreover, as discussed in the following sections, these gaps appear to have deepened over time while income inequality also increased, particularly from 2014/15 onwards.

Concerning the widening north–south socioeconomic gaps, there is evidence that while in most of the populated centre-north, the main economic activity has remained agriculture, especially low-productivity subsistence agriculture, characterised by smallholders cultivating plots of less than one hectare on average (Donovan and Tostão 2010; Carrilho et al. 2023), the economy became increasingly diversified in the southern part of the country. This was due to the extraordinarily rapid development of the service sector, formal and informal trading, investment links with South Africa, the growth of the tourism sector, and the creation of special economic zones (Cunguara et al. 2012; Castel-Branco 2002; Nucifora and da Silva 2011; Cruz and Mafambissa 2019; Cruz, et al. 2023, among others). Moreover, among the drivers of regional poverty disparities, it is important to note increased availability of publicly provided services (health, education, electricity, roads, etc.) in the southern region; this has over the years contributed to lowering the time and costs to reach schools and other facilities, public transportation, and other services, thus gradually improving people’s livelihoods and opportunities. Added to this are higher education institutions which are disproportionally located around the capital area, allowing individuals living in the south access to better-paid, formalised, jobs. The capital Maputo in the very southern part of the country meant that many government and public institutions jobs were filled by people living in the area (DEEF 2016; INE 2015, 2021).

As a matter of fact, the Fourth National Poverty Assessment argued that

…[d]ue to the concentration of the Mozambican work force in subsistence agriculture and low productivity informal enterprises, it is also clear that Mozambique is – in spite of the progress realized – characterized by very high levels of individual and household vulnerability. […] These observations hold throughout the country but are particularly pertinent to the rural zones of the North and Centre, where, at this point in time, the very large majority of poor people reside (for all of the welfare metrics considered). These facts and the findings in this report inescapably imply that future dynamics in smallholder agriculture and the informal sector will be of fundamental importance to achieving continued broad based progress in welfare enhancement over at least the next decade and likely longer than that. […] In sum, achieving inclusive growth is the core policy challenge facing Mozambique in its economic and social development over the next decades […] (DEEF 2016).

Addressing existing spatial inequalities has thus become a key goal for both public and international institutions. Several initiatives have been implemented by the national government and various development partners aimed at reversing this situation, with different degrees of success. Among the area-specific initiatives, there is, for instance, the creation of special governmental agencies for the development of particularly deprived areas. An example is the Zambezi Valley Development Agency which carries out studies and strategies for economic and social development in the Zambezi River Basin, also providing technical and financial assistance to economic and social development initiatives including the mobilisation of resources and their channelling to beneficiaries. Another example is the recently created Agency for the Integrated Development of the North, which was designed to address the lack of jobs and opportunities for people in the northern region. This was justified by the fact that many young, jobless, poor, and desperate individuals were found to be an easy target for the armed insurgents who are fuelling the conflict that started in 2017 in the resource-rich northern province of Cabo Delgado (Ewi et al. 2022). This agency promotes an array of actions aimed at the socioeconomic development of the provinces of Niassa, Cabo Delgado, and Nampula, with a view to improving the quality of life for communities.

Meanwhile, other area-specific initiatives concentrate on the so-called development ‘corridors’. As in other African countries, during colonial times corridors were created in Mozambique by the European colonial powers to facilitate the flows of resources, goods, and knowledge between coastal areas, urban centres, and their hinterlands. The three main transnational corridors in Mozambique were centred on the cities of Maputo, Beira, and Nacala (Kirshner and Baptista 2023). These corridors are important routes for the development of infrastructure, trade, and economic activity; both the government and other institutions have taken advantage of the pre-existing improved infrastructural and socioeconomic conditions around these areas over the years to radiate better prosperity starting from these key connecting routes. One example in this context is the Maputo Port Development Company (MPDC), which is a national private company promoting growth in the area through the development of port services. Another example is the ProSAVANA project which started developing in the 2010s as a gigantic multilateral agricultural development programme centred around the Nacala Corridor. Yet another example is the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor (BAGC), a public–private partnership which was launched in the 2010s to establish an agricultural growth corridor encompassing the central provinces of Tete, Manica, and Sofala, with links to Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi (Kirshner and Baptista 2023).

However, especially as regards the last two initiatives, it seems that poor consultation and information sharing led to smallholders feeling, at times, marginalised and not integrated into the projects thus fuelling contestations and poor engagement of local populations (Gonçalves and Sulle 2023). Finally, the identification and creation of integrated growth poles is a policy that has been explored in the country. The World Bank has, for example, financed a multi-year project to improve the performance of enterprises and smallholders in the Zambezi Valley and Nacala Corridor, focusing on specific growth poles—such as the Tete agribusiness growth pole and the Nacala Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the Nacala Corridor—explicitly aimed at supporting shared and equitable growth (World Bank 2010, 2013). Several other growth pole projects have taken place over the last decade or so; however, some recent reviews argue that the country does not seem to have adopted the strategy in a very convincing way (Joaquim, Armando, and Tundumula 2022).

Overall, notwithstanding various attempts to achieve a more equitable growth and development process in the Mozambican setting, even by the end of the 2020 and after significant improvements had taken place at national and sub-national level, only about 60% of the rural population lived in a household in which at least one member had completed primary school (five years of education) (this percentage was equal to about 90% in urban areas). Similarly, as much as 64% and 83% of the rural population was deprived in its access to safe water and sanitation (respectively, 23% and 38% in urban areas), and where 70% of the population residing in rural areas did not have quality roofing, 90% of the same population did not have access to electricity (these percentages averaged 21% and 27%, respectively, in urban areas) (see DEEF 2016; DNPED forthcoming; and Sect. 'Conclusions' for details).

Returning to the impacts of recent shocks experienced between 2014/15 and 2019/20, recent analyses show that these contributed to partially altering the structural characteristics of deprivation in the country. In particular, a generalised surge in monetary poverty appeared due, among other variables, to the way the country managed and reacted to a debt crisis during 2015–17 (Salvucci and Tarp 2023b); an increase in poverty in the northern province of Cabo Delgado, plagued by an armed conflict that started in 2017 and is still ongoing; increased deprivation in the areas of Beira and, again, Cabo Delgado, after two major cyclones hit in 2019; more widespread deprivation in urban areas and the more urbanised southern region following the health and economic shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and, in particular, by the pandemic-related restrictive measures applied (Salvucci and Tarp 2023a).Footnote 2

In this paper, we apply an innovative multidimensional poverty evaluation method, based on first-order dominance (FOD). The contribution of our study is to customise and apply the FOD method to all existing household budget survey data for Mozambique with the objective of assessing how multidimensional poverty has evolved over time and, in general, to test the robustness of the consumption poverty results.

We are motivated to use the FOD method as an analytical tool based on our objective to overcome some of the widely acknowledged constraints inherent to other popular methods to estimate multidimensional poverty, such as the Alkire–Foster (A–F) approach. These will be analysed in detail in the methodology section and include issues such as the choice of weights attributed to each welfare dimension/indicator and the choice of the cut-off used to characterise people as multidimensionally poor or not. The FOD method attempts to overcome both of these issues while trying to maintain basic consistency with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights principles (Arndt et al. 2018) and comparability/complementarity with the A–F approach. A particular advantage of the FOD method is that conclusions about comparative levels of deprivation and trends are tested in an extremely robust manner.

In addition to providing a different and analytically demanding perspective on the evolution of poverty in Mozambique, applying FOD methodology allows us to examine the sensitivity of A–F outcomes—analysing multidimensional poverty with FOD is especially relevant in Mozambique because it allows for comparing welfare attainments for different sub-populations in a rigorous manner. Indeed, as noted, Mozambique presents stark urban–rural and regional inequalities in multidimensional poverty along multiple dimensions.

The paper proceeds as follows. The Sect. 'Literature review and poverty trends' reviews existing literature on the application of the FOD approach to multidimensional poverty measurement and further describes poverty trends observed over time. The Sect. entitled 'Methodology' sets out our methodology, while the Sect. 'Data and welfare indicators' addresses data issues: the variables used for FOD estimation and their statistics. We present our results in Sect. 'Results', focusing on the temporal and spatial dominance at the national, urban–rural, regional, regional-urban–rural, and provincial levels, while the Sect. 'Summary and discussion' discusses and summarises the findings. The Sect. 'Conclusions' concludes.

Literature review and poverty trends

In this section, we first review various studies that have used the FOD approach to analyse poverty measurement. Subsequently, we summarise the main results from official reports and additional studies that have analysed poverty (either consumption or multidimensional poverty) levels and trends in Mozambique.

Literature review

Here we review the studies that used the FOD approach to analyse poverty measurement, focusing on the few that have used the FOD approach to analyse multidimensional poverty and that had a special focus on Mozambique and/or other developing countries.Footnote 3 Based on small area estimation techniques and applying the (FOD) approach, Arndt et al. (2016a) used the 1997 and 2007 population censuses for Mozambique and the 1996/97 and 2007/08 Mozambican household budget survey data to analyse well-being at the district level. Their results, based on 146 districts, indicated that the most deprived districts are located in the northern and central areas. None of the southern districts appear in the lowest-ranked group. Also, as it emerged in the headcount ratio analysis (poverty mapping), the FOD results showed that disaggregating the analysis to district level provided additional information on intra-province welfare differences.

In 2007, most of the FOD lowest-ranked districts were again located in the central and northern provinces, while most of the southern districts were confirmed as the FOD best-ranked ones. Looking at the FOD temporal index, no district performed better in 2007 than its 1997 performance. There were 76 districts (out of 146) for which the probability of experiencing welfare improvement was higher than 50%. Given the strictness of the FOD criterion, this is a salient result confirming broad-based advances in living conditions between 1997 and 2007.

Egger et al. (2023) suggested that the poverty reduction trend observed between 2009–11 and 2015 decelerated rapidly, and that the poorest provinces had generally not improved their rankings over time. They reached these results using the standard A–F multidimensional poverty index and the FOD method, both applied to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), the AIDS Indicator Survey (AIS), and the Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) data for Mozambique. Moreover, they found that the percentage of people with zero deprivations only slightly increased during 2015–18, whereas the percentage of people with the maximum number of deprivations experienced a modest reduction at national level and actually increased in urban areas even if only slightly. The estimated probability of advancement between 2015 and 2018, as measured by the temporal FOD approach, was virtually zero for most areas and provinces. These results pointed to a troubling intensification of poverty when focusing on the absolute numbers of people. Indeed, the study found that the number of multidimensionally poor people had increased, mainly in rural areas and in the central provinces.

Comparing Mozambique with Vietnam, Arndt et al. (2012) used the FOD approach to analyse child poverty in the two countries. The results indicated that Vietnam saw an increase in well-being at the national level, in rural zones and in two regions. There was essentially no probability of regression through time in any region. These results provided evidence that gains over the 2000–06 period were reasonably broad based. Conversely, Mozambique registered fewer gains. As in Vietnam, there was essentially no evidence of regression through time, but there was a positive probability of advancement only at the national level, in rural zones and in six of the 11 provinces. However, these probabilities tended to be relatively small.

Permanyer and Hussain (2018) undertook a broader analysis of multidimensional welfare in developing countries using the FOD methodology and applied it to 48 DHS datasets, mostly from 2006–12. Their results suggested that the highest observed number of dominations was for Ukraine, which dominated 45 countries, i.e. conditions in Ukraine were comparably better. Eleven countries, including Mozambique, did not dominate other countries (Burkina Faso, Benin, Burundi, Ethiopia, India, Liberia, Moldova, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, and Rwanda); 31 countries dominated Mali, while 28 other countries dominated Ethiopia and Liberia. Only two countries did not experience dominance by other countries (Ukraine and Armenia).

In summary, most of the existing analyses of multidimensional well-being in countries, either focusing on or including Mozambique, indicate that achieving robust poverty reduction and, in particular, inclusive growth in the country remains a major challenge. The central and northern provinces, and especially rural areas, lag behind in terms of poverty and well-being. Moreover, convergence between better-off and more deprived areas and provinces remains elusive.

Consumption and multidimensional poverty trends

We now turn to providing additional insights regarding the consumption and multidimensional poverty results contained in the four national poverty assessments, DNPO (1998, 2004), DNEAP (2010) and DEEF (2016), supplemented with the 2019/20 data analysed by DNPED (forthcoming). As discussed in the introduction, these reports demonstrate that Mozambique followed a steady development path from mid-1990s to mid-2010s.

From a macroeconomic point of view, Mozambique recorded very high GDP growth rates in the years 1996–2001, in large part explained by the recovery process that took place after a 17-year-long armed conflict that only ended in 1992. These rates averaged about 10%, and in subsequent years, 2002–15, they remained at relatively high levels, around 7.5% (World Bank 2023a). Within the same time span, consumption poverty reduced from about 70% to 46%. The trend included a substantial fall in poverty between 1996/97 and 2002/03, whereas the national poverty rate stagnated between 2002/03 and 2008/09, and poverty decreased again between 2008/09 and 2014/15 (DNPO 1998, 2004; DNEAP 2010; DEEF 2016; INE 2004, 2010, 2015; Arndt et al. 2012, 2016a, 2018; World Bank 2018, 2020, 2021, 2023b; DNPED forthcoming).

It has been argued that this positive trend reversed in 2015 when a series of shocks—spanning from weather-related events to economic crises and armed insurrections—hit the country (World Bank 2023b; Egger et al. 2023; Salvucci and Tarp 2023a; 2023b; DNPED forthcoming). It was mentioned in the introduction how this unprecedented series of shocks severely impacted the Mozambican economy, with GDP growth rates falling, and consumption poverty rates increasing to levels similar to those experienced at the end of the nineties (World Bank 2023a). DNPED (forthcoming) and GdM (2024) report that the national poverty headcount increased to 68%, with even higher rates in rural areas, and in the centre and north (see Table 1, panel a).

It is worth noting that the results presented are based on the national poverty line, as computed by the Mozambican Ministry of Economics and Finance (MEF). This represents the cost of acquiring a basic basket of food and non-food items able to provide the necessary amount of calories for an active life. A different poverty line is computed in each survey round based on the consumption patterns of the poorest part of the population in each of the spatial domains considered (see DEEF 2016; Barletta et al. 2022b). The values of the national poverty lines computed in various survey rounds have generally been lower than the international poverty line counterparts—previously equal to US$1.90 and recently revised to US$2.15 (Jolliffe et al. 2022)—meaning that the poverty rates obtained using the international poverty lines, and reported in most international institutions’ data banks, are usually higher. With respect to the tendency followed by the value of the nationally computed poverty line, this grew approximately steadily until 2014/15, but it increased more markedly between 2014/15 and 2019/20. This means that the cost of acquiring a basic basket of food and non-food items increased and, therefore, fewer households could afford it.

Salvucci and Tarp (2023b) argue that the economic crisis that started in the second half of 2015, following the debt crisis, led to a significant devaluation of the national currency and, in turn, to a general increase in prices, especially food prices, and that this impacted poverty and welfare significantly. Moreover, the depth of poverty also soared during the same period: the poverty gap almost doubled, from about 17% to about 32% in just five years (DNPED forthcoming). This represents a huge increase as it means that, in consumption terms, the average distance of the poor population to the poverty line was only about 17% of the value of the poverty line in 2014/15, but this percentage rose to 32% by 2019/20.Footnote 4 At the same time, income/consumption inequality, as measured by the Gini index, also increased, especially in the last 10–12 years (see also Barletta et al. 2022; Gradín and Tarp 2019; World Bank 2018).

Turning to the main focus of our paper, DEEF (2016) also informs that multidimensional poverty followed a rapidly decreasing trend during 1996/97–2014/15. However, welfare indicators composing the multidimensional poverty measure adopted in the country were also negatively affected by the above shocks, and the improvement registered during 2014/15–2019/20 was very modest (Table 1, panel b) (Egger et al. 2023; DNPED forthcoming).

Six indicators are considered in the national poverty assessments contained in DEEF (2016) and DNPED (forthcoming): completion of primary education, access to safe water, sanitary conditions, housing coverage quality, access to electricity, and possession of some basic durable goods. The percentage of the population categorised according to the number of deprivations suffered is displayed in Table 1, panel c, whereas in Table 1, panel b, we present the multidimensional poverty incidence, H, estimated using the A–F method for the period 1996/97–2019/20 (Alkire et al. 2015a, b; DEEF 2016; DNPED forthcoming).

This A–F measure indicates the percentage of the population considered poor from the multidimensional point of view, given the welfare dimensions/indicators selected, the weights assigned to the indicators and dimensions, and the cut-off chosen to distinguish the poor from the non-poor. The multidimensional poverty incidence, H, was 55% in 2014/15, at a lower level than in 2008/09, and at a much lower level than 1996/97. However, multidimensional poverty incidence only reduced to 53% in 2019/20. The same table shows variations by areas/province, with multidimensional poverty being significantly worse for the northern and central regions of the country and for rural areas, as already highlighted in the introduction.Footnote 5 Both the monetary and A–F multidimensional poverty results, at the provincial level and for the most recent survey, 2019/20, are also depicted in Fig. 2, which emphasises the already noted geographical disparities, especially for what concerns multidimensional deprivation.

Consumption poverty rates (headcount), multidimensional poverty incidence (H), 2019/20 (%). Note: percentage of consumption poor people over the total population (Headcount) and multidimensional poverty incidence obtained using the A–F method (H), for 2019/20 (%).

The decreasing trend in multidimensional poverty is also confirmed when different data sources are used, such as the population censuses or the DHS data. Using essentially the same welfare indicators adopted in the evaluation of multidimensional poverty using the household budget surveys, and applying the A–F methodology, the census data show that multidimensional poverty decreased both between 1997 and 2007 and between 2007 and 2017, more substantially in the latter period. The multidimensional poverty incidence, H, fell from about 87% to about 77% over 1997–2007, and it decreased to about 48% in 2017 (Cardoso, Morgado, and Salvucci 2016; Cardoso et al. 2021; DNPED 2020).Footnote 6

With respect to the DHS data, Egger et al. (2023) analysed the evolution of multidimensional poverty in Mozambique applying the A–F method and using the 2011 DHS, the 2009 and 2015 AIDS Indicator Surveys (AIS), and the 2018 Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) data. Consistent with the evolution of poverty described in the four available national poverty assessments, they find that the multidimensional poverty reduction trend observed between 2009–11 and 2015 effectively stagnated between 2015 and 2018. However, the number of people who were poor by this measure increased, mainly in rural areas and in the central provinces (Egger et al. 2023).

Poverty analyses using the FOD approach also exist for Mozambique, mainly as part of the Fourth National Poverty Assessment (DEEF 2016). From the spatial point of view, this assessment applied the FOD procedure at the provincial level and it emerged that the rankings obtained until 2014/15 were very stable over time, contrary to what happened for the provincial rankings relative to the consumption poverty measures. Moreover, the provinces of Maputo City, Maputo Province, and Gaza always rank first, second and third, respectively, whereas the provinces of Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula, Zambezia, and Tete remained in the bottom five positions in all surveys until 2014/15.

In addition, with regard to changes over time, the FOD method applied to the 1996/97, 2002/03, 2008/09, and 2014/15 surveys provided important indications on the probability for each province or region of the country to be in an improved welfare situation, from a multidimensional point of view, compared to previous years. From the same assessment, it emerges that for the country as a whole and up to 2014/15, the probability of advancement is equal to one (100%) in most comparisons. This result suggests, with a high level of confidence, that at the national level, the multidimensional well-being situation improved until 2014/15. Nevertheless, at the same time, the north and, in particular, rural areas of the north showed the lowest probabilities of improvement (DEEF 2016).

Methodology

Poverty is a multidimensional phenomenon. As such, analyses relying on standard methods based on income or consumption cannot stand alone. Non-monetary deprivation is key.

The study of poverty as a multidimensional and complex phenomenon has developed from at least the mid-1970s, when a stream of literature and analysis started to explicitly recognise the multidimensional nature of poverty and deprivation. Multidimensional poverty measures and assessments gradually evolved alongside more traditional methods, providing complementary or alternative insights into various forms of deprivation suffered by the poor compared to the approaches based solely on income or consumption. These multidimensional methodologies started to consider additional non-monetary dimensions—such as education, health, and basic infrastructure services. The idea and main objective behind these measures are to capture the complexity of poverty by looking beyond monetary deprivations.

Several of the multidimensional poverty applications that have been developed in recent decades are rooted in the seminal works regarding the capability approach initiated by Sen (1974, 1979a, 1979b, 1985, among others). The popular Alkire–Foster method, which is often used as a reference in this and other studies, but also the FOD approach and others, can all be considered as attempts to implement in practice the theoretical intuitions originating from the early analyses of Sen and other authors. Nonetheless, graduating from theory to practice required accepting some compromises (Alkire 2016). Both the Alkire–Foster and the FOD approaches, for example, belong to the wide category of analytical methods that compute multidimensional poverty based on the joint distribution of deprivations. This entails that household- or individual-level information is available regarding each deprivation dimension or indicator used (Alkire et al. 2015b). These approaches are thus relatively more demanding in terms of data availability than methods that are based only on aggregate information at country or other sub-national levels.

Consequently, it frequently so happens that data about important dimensions for individual well-being—such as freedom, life satisfaction, general health status, among others—end up not being considered because of lack of underlying data. In addition, the data usually available about deprivation dimensions or indicators likely reflect achieved functioning (of what an individual chooses to do or to be) more than capabilities.Footnote 7 A notable example is the global multidimensional poverty index (Global MPI), developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) (UNDP and OPHI 2019). It measures multidimensional poverty using the Alkire–Foster method based on 10 indicators (nutrition, child mortality, years of schooling, school attendance, cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity, housing, assets), grouped in three dimensions (health, education, living standards). Another example is the World Bank’s Multidimensional Poverty Measure (MPM), which considers both monetary poverty (consumption levels below US$2.15 per day) and non-monetary deprivations (World Bank 2024).

The methodology implemented by the government to assess multidimensional poverty was developed within the framework of the Fourth National Poverty Assessment (DEEF 2016) and includes the selection of the welfare indicators based on (i) the relevance of the indicator; (ii) the existing literature; (iii) the availability of the indicators in all surveys up to 2014/15; and (iv) a public consultation process undertaken in all regions of Mozambique, conducted in collaboration with UNDP and UNICEF (DEEF 2016).

Given the limited availability of welfare indicators (not all the indicators were available in the surveys considered, especially in earlier rounds undertaken in 1996/97 and 2002/03), and, at the same time, the strong wish to maintain comparability over time, it emerged that it was not possible to use all the dimensions and indicators found in the Global MPI or in the World Bank’s MPM. Therefore, the national poverty assessments produced after 2014/15 eventually considered only six welfare indicators (DEEF 2016; DNPED forthcoming).

In this study, we decided to maintain consistency with the national poverty assessments for Mozambique so as to provide a comparable assessment of multidimensional poverty and deprivation for the country. Therefore, the present analysis uses the same six welfare indicators considered in DEEF (2016) and DNPED (forthcoming). They were briefly mentioned in the previous sections and include completion of primary education, access to safe water, sanitary conditions, housing coverage quality, access to electricity, and possession of some basic durable goods. Further details follow in the data section.

In both the A–F and the FOD approaches, the welfare characteristics of interest are first transformed into binary indicators (deprived/not deprived). Then, in subsequent steps, the two methods differ. In the A–F approach, indicators are generally grouped into welfare dimensions; then dimensions, and indicators within each dimension, are assigned a weight depending on their relative importance; finally, a cut-off is chosen so that households whose weighted sum of deprivations is above the cut-off are considered poor, and households below the cut-off are categorised as non-poor. Based on the above considerations, measures of poverty incidence, poverty intensity, and adjusted poverty incidence are computed (Alkire and Foster 2011, 2015a).

It follows that the A–F method requires a series of decisions by the analyst regarding the way in which categorical or continuous welfare indicators are transformed into binary variables, the weights to be assigned to welfare indicators and dimensions, and the cut-off to separate the (multidimensionally) poor households from the non-poor. Even though a relatively large literature has emerged guiding these choices, and a standard for these procedures has been set by the timely publications of the Global MPI in which the A–F method is applied to most developing countries (UNDP and OPHI 2019), concerns with respect to the arbitrariness of the decisions involved are not completely resolved. The choices with respect to the relative importance of different welfare dimensions/indicators seem particularly delicate in this framework, leading analysts to explore the robustness of the MPI to different choices of the weights or of the cut-off (Jones 2017).

Moreover, Arndt et al. (2018) argue that the A–F multidimensional poverty index is in reality inconsistent with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights principles of indivisibility, inalienability, and equality, due to the dependence on a weighting scheme and the underlying assumption about substitutability between the welfare indicators included. Hence, we are motivated to use the FOD method as an analytical tool in the present context to attempt to overcome some of the above mentioned and acknowledged constraints inherent to the Alkire–Foster (A–F) method for the estimation of a multidimensional poverty index (MPI).

With respect to the A–F-related choice of weights attributed to each welfare dimension/indicator and the choice of the cut-off used to characterise people as multidimensionally poor or not, the FOD approach only relies on the proposition that a not deprived state is better than being deprived for any welfare dimension considered.Footnote 8 Indeed, it is possible to identify, using multiple binary indicators, states that are arguably better and states that are arguably worse (e.g. being not deprived in all dimensions can arguably be considered a better state than being deprived in all dimensions) without the need to rely on weights to evaluate the relative importance of each welfare dimension. That is, the FOD method does not impose restrictive assumptions on utility or social welfare functions. Additionally, it allows us to rank welfare attainment in different sub-populations—related to spatial comparisons of multidimensional welfare between different provinces, regions, or districts, or temporal assessments between provinces, regions, or districts over time—without imposing a specific threshold to define households as poor. Rather, the only requirement we impose is that we rank the outcomes within each dimension from better to worse.

Moreover, with respect to the inconsistency of the A–F approach with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights principles of indivisibility, inalienability, and equality, it is worth noting that Arndt et al. (2018) also discuss how the FOD methodology maintains basic consistency with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights principles. They note that:

FOD comparisons are independent of any applied weighting schemes and hence are free from assumptions regarding substitutability between included welfare indicators (indivisibility). FOD cannot be established when welfare in any indicator is deteriorating, no matter how great the advancement is in other indicators (inalienability). Finally, FOD requires that domination occurs throughout the population (equality), implying that welfare gains among better-off groups never offset welfare losses among worse-off groups.

This leads to the conclusion that the A–F MPI and FOD approaches may be useful complements when analysing multidimensional welfare.

We now turn to the FOD welfare comparisons in practice, and available choices on how to deal with indeterminate comparisons, with some examples, including a summary of the methodology.Footnote 9 Following Arndt et al. (2012, 2016a), Arndt and Tarp (2017), Egger et al. (2023), among others, a population A is said to first-order dominate (FOD) another population B if one can shift probability mass within population A from states that are unambiguously better to states that are unambiguously worse and replicate the distribution of population B. For example, if only two binary indicators are considered, where 0 means deprived and 1 means not deprived, the states (1,1), (1,0), and (0,1) are better than the state (0,0). Given the percentages of households in each state and in the two populations, if one could replicate the distribution found in B by shifting probability mass within population A only from better to worse states, then A first-order dominates B. This entails that in order to replicate the distribution found in B, one could shift probability mass within population A from the state (1,1) to the states (1,0), (0,1) and (0,0); or that one could shift probability mass from the states (1,0) and (0,1) to the state (0,0). However, shifting probability mass from the state (1,0) to the state (0,1), and vice versa, is not permitted, because it is not possible to argue that the state (1,0) is unambiguously better the state (0,1), and the comparison is therefore indeterminate.Footnote 10

When the comparison occurs between three or more populations, it is still possible to rank them by counting the number of times a given population first-order dominates the others, the times the same population is dominated by the others, and computing the difference (net domination). The resulting score can be subsequently normalised so as to fall within the interval [-1,1] (Copeland 1951).

In Arndt et al. (2012, 2016a) and Arndt and Tarp (2017), a method based on bootstrapping techniques was also devised to allow population rankings in cases in which comparisons are indeterminate. Its application permits to derive domination probabilities, which can in turn be used to rank several population categories, such as regions within a country, different countries, or a region or a country at different points in time. When regions within a country or different countries are analysed, we talk about spatial FOD analyses, and when instead the welfare situations of a region or of a country observed at different points in time are assessed, we talk about temporal FOD analyses.

The complexity of the FOD approach, together with its less straightforward interpretation, makes this method relatively less appealing for large-scale applications. This is also because when the number of welfare indicators considered increases, the number of comparisons to be performed makes its application computationally intense. Nevertheless, the fact that it does not require any assumptions with respect to the relative importance of different dimensions/indicators of multidimensional poverty represents a noteworthy advantage with respect to other methods. This also entails that consistency between the multidimensional poverty results obtained applying the FOD or other methods, including the A–F one, is not automatic.

Data and welfare indicators

The present analysis is based on five household budget surveys (Inquéritos aos Agregados Familiares sobre Orçamento Familiar), undertaken in Mozambique in 1996/97, 2002/03, 2008/09, 2014/15, and 2019/20. These are abbreviated as IAF96, IAF02, IOF08, IOF14, and IOF19. While the data collection was in all cases undertaken by the national statistics office (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, INE), the poverty analysis has always been carried out by the Ministry of Economics and Finance (MEF) or its equivalents. The surveys are designed in a similar way. First, they are representative at the national, urban–rural, regional, and provincial levels. Second, data collection takes place over the period of approximately 12 months divided into four quarters, with households interviewed once over this period.Footnote 11 Third, information collected includes household characteristics, education, employment, consumption expenditure, possession of durable goods, housing conditions, receipts, transfers, income, and other characteristics.

With respect to multidimensional welfare, six indicators were selected in the framework of the Fourth National Poverty Assessment, and subsequent analyses have relied on the same indicators (DEEF 2016; DNPED forthcoming). As already explained, the selection of the welfare indicators depended on: (i) the relevance of the dimensions and indicators with regard to well-being, also based on the relevant literature; (ii) the availability of similar information in all surveys; (iii) the comparability of the questions included across all the surveys; and (iv) a consultative process, conducted in collaboration with UNDP and UNICEF (DEEF 2016).

The availability of similar information in all surveys particularly limited the choice of welfare indicators, mainly due to the lack of comparable welfare indicators in older surveys—the IAF96 (and, to a lesser extent, the IAF02). The six selected indicators are described in more detail in Table 2.Footnote 12 The same indicators are used to evaluate deprivation in both urban and rural settings, and in all regions.Footnote 13

Results

We now proceed to our results, beginning with descriptive statistics for all indicators in all surveys. Hereafter, we introduce the spatial and temporal FOD results, respectively, discussing them in relation to existing poverty results. We end with our robustness check with respect to the assessment of multidimensional poverty using the census data for 1997, 2007, and 2017 instead of the household budget survey data.

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 shows the deprivation levels for each selected indicator in 1996/97, 2002/03, 2007/08, 2014/15, and 2019/20, for the total national population and differentiated at urban/rural, and regional levels. In general, the results show a reduction in the level of deprivation over the period under review for all indicators, with some exceptions with respect to water source and possession of durable goods in the last period. Furthermore, there are differences in the speed of reduction or increase between the analysed indicators, at the regional level and by area of residence (rural or urban), with access to education, electricity, and quality sanitation standing out among the indicators of rapid improvement.

A large part of the population remains deprived in some indicators, mainly those referring to housing conditions, such as access to safe water and sanitation, electricity, good-quality housing coverage, and possession of durable goods, particularly in rural areas. Nonetheless, the deprivation status of the rural population in relation to sanitation (which is also considered an important determinant of health) and housing conditions (type of coverage, electricity) in 2019/20 has improved compared to the levels recorded in 2014/15. Conversely, despite the difference in deprivation in terms of area of residence, deprivation in water and in durable goods, increased only slightly with respect to the former and more markedly with respect to the latter.

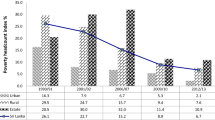

In particular, the increase in durable goods deprivation in 2019/20 is only in rural areas. This may indicate that some rural households could have been selling durable goods to sustain consumption/living standards in response to consumption shocks or that climate shocks destroyed some durable goods. Another explanation could come from the fact that radios and bicycles, the two items for which ownership decreased the most, are not anymore as relevant as they were in previous years. However, while in urban areas it seems as though they were replaced by better substitute items, such as TVs/computers and/or motorbikes/cars, this was not the case in rural areas, where it appears as they were simply abandoned. Results at national level are displayed in Fig. 3.

Prevalence of deprivation for selected welfare indicators, national level, 1996/97–2019/20 (%) Note: Prevalence of deprivation (in percentage) for each deprivation indicator considered in the multidimensional poverty assessment, national level, 1996/97–2019/20.

Spatial FOD comparisons and rankings

In Table 4, we present the rankings obtained applying the FOD procedure to the comparison of different spatial aggregates, providing a more detailed overview of the evolution of relative welfare in the country. In this table, we use spatial bootstrap FOD results to compare different area aggregates based on the net probability of domination (PND), that is, the average probability that an area dominates all others minus the average probability of domination by all other areas.Footnote 14

From the net probability of domination and ranking results, we conclude that they largely confirm the general trends and spatial divide outlined in the Sect. 'Literature review and poverty trends'. A marked division between the urban areas and the three most southern provinces (Gaza, Maputo Province, Maputo City; see Fig. 1) and the rest of the country is evident, especially when compared to the northern provinces (Cabo Delgado, Niassa, Nampula) and to Zambezia, and particularly to their rural areas. This split is consistent over the years, and most area aggregates show no change in their ranking, compared to either 1996/97 or 2014/15, or change it by only ± 1- ± 2 positions. The rankings based on the net domination probability are thus very stable over time.

In particular, Maputo City dominates all other provinces and areas (the net domination probability is close to or equal to one in all years), but Maputo Province markedly improved its ranking over time, becoming the second best-off area in 2019/20. Together with Maputo Province, also the province of Tete and the rural areas of the southern region improved their ranking significantly over time (by five and four positions, respectively). For Tete, this reflects developments subsequent to the discovery of important coal reserves in the last 10–15 years, and for the rural areas of the south, this links to the fact that southern rural areas are progressively urbanised and are thus assuming more urban characteristics with respect to other rural areas of the country. To this comes the relative closeness to the capital area that has had a positive effect in terms of improvement in some of the welfare indicators selected (easier access to services, increased availability of durable goods and of better-quality construction materials, among others). Conversely, the national average was in 2019/20 in a much worse position with respect to past surveys, with stability at the bottom of the list. The central region, the provinces of Cabo Delgado and Nampula, the northern region, the province of Niassa, the rural areas, the province of Zambezia, the rural areas of the central region, and the rural areas of the northern region are low performers with few changes in their respective position between one survey and the other.

Given the strictness of the FOD approach, it is remarkable that such a clear and consistent ranking structure emerges. Even though we cannot have in the FOD framework, an absolute measure of how distant (or how much worse off) the lower-ranking areas are in terms of multidimensional deprivation compared to the better-off areas, these findings depict a situation of persistent spatial gaps in deprivation. If not addressed, they will certainly become problematic and hamper future broad-based developments, including peace and stability, as further discussed in sect. 6 and 7. We also note that these results are largely comparable to those obtained by DNPED (forthcoming) using the A–F method. For example, in 2019/20, while the incidence of multidimensional poverty was just slightly above 0% in Maputo city, it still exceeded or was close to 60% in Cabo Delgado, Niassa, Nampula, Zambezia, and Tete.

To substantiate the claim that FOD results are consistent with those obtained using the A–F method, we show in Table 5 the correlation coefficients between the PND computed using the FOD procedure and the A–F multidimensional poverty incidence (H), for all years. They are below -0.90 in all cases—that is, areas in which the multidimensional poverty incidence is very high are also areas that fail to dominate other areas and have a high probability of being dominated by other areas. We also show the Spearman's and Kendall's rank correlation coefficients, for all years, based on the ranks obtained from FOD and A–F. In this case, they are very high and above 0.90 in almost all years, meaning that the poverty rankings obtained using the two procedures are very similar. To compare, the correlation between the A–F multidimensional poverty incidence (H) and the consumption poverty rate is generally lower, especially in 2002/03 and 2008/09 (Table 5). Even from a visual analysis, contained in Fig. 4, it is possible to confirm that the PND computed using the FOD procedure and the A–F multidimensional poverty incidence, at provincial level, deliver comparable results.

Alkire–Foster multidimensional poverty incidence (H) and FOD net domination probability (PND) (%), 2019/20. Note: PND = net domination probability (i.e. the probability of dominating other areas minus the probability of being dominated by other areas); H = Alkire–Foster multidimensional poverty incidence.

Temporal FOD comparisons

Temporal domination, as discussed in methodology section, measures the probability of advancement in the area examined between two time periods. Table 6 reports temporal net FOD comparisons between 1996/97, 2002/03, 2008/09, 2014/15, and 2019/20 using the six welfare indicators described. As for the spatial FOD comparisons, we present the probabilities of advancement computed using bootstrapping methods. The numbers in Table 6 represent in this case the average net probability of domination computed across all bootstrap iterations, that is, for each area, the probability of being in a better situation according to the FOD criterion minus the probability of being in a worse situation, according to the same criterion (i.e. the probability of advancement minus the probability of regression between the two years being analysed).Footnote 15

The analysis of the temporal FOD provides important indications of the probability for each area of the country to be in a better situation, from a multidimensional point of view, compared to previous years. When the comparison is indeterminate, we show no probability (in the table). This means that it is not possible to state whether the area considered is in a better situation (according to the FOD criterion) compared to the previous surveys. We observe immediately that, for the country as a whole, the probability of advancement is equal to one (100%) in most comparisons: 2002/03–1996/97, 2008/09–1996/97, 2014/15–1996/97, 2014/15–2002/03, 2014/15–2008/09, 2019/20–1996/97, 2019/20–2002/03, and 2019/20–2008/09.

This suggests, with a high level of confidence, that at the national level, the multidimensional well-being situation improved over time, which can be interpreted as an improvement, on average, in every indicator in almost every spatial aggregate between 1996/97 and 2019/20. Before 2014/15, the lowest probability of improvement is found in the comparison between 2008/09 and 2002/03 (51%), which supports those analyses based on consumption poverty in which it was reported that poverty had mostly stagnated between 2002/03 and 2008/09. Similar trends are obtained when probabilities of improvements are calculated for provinces only (DEEF 2016).

However, the most striking result is probably the one concerning the comparisons between 2019/20 and 2014/15. Consistently indeterminate results appear for most area aggregates, and for those areas for which it is possible to establish an FOD comparison, the probability is very low and close to zero. Because of the inherent characteristics of FOD comparisons, one or two indicators following a pattern that diverges from the general trend may cause indetermination. For example, in a scenario such as the Mozambican one, where almost every indicator follows a constant upwards trend over the years, regression or stagnation in just a single indicator can lead to such an indeterminate result. Hence, it does appear as if the situation at national level and for most areas in 2019/20 was clearly better than it was in 1996/97, 2002/03, and 2008/09 (the net probability of domination is equal to one in most comparisons).Footnote 16 However, it stands out that using the FOD approach we cannot conclude that the multidimensional deprivation status in 2019/20 was better than it was in 2014/15.

When applying the FOD technique, obtaining results as clear-cut as the ones discussed here is not common. However, this is as might be expected in the context of Mozambique. In 1996/97, the year of the first survey considered here, Mozambique had just emerged from an armed conflict which had torn the country apart, then followed sustained economic growth and relatively broad-based improvements in household welfare which spanned twenty years after the end of the conflict. The magnitude of these advancements is highlighted in the Fourth National Poverty Evaluation and other analyses (DEEF 2016; Egger et al. 2023). The Fourth National Poverty Evaluation revealed substantial improvements across all the indicators used. Accordingly, it found that the multidimensional poverty index, computed using the A–F method, had decreased steadily in all the sub-populations considered. From 2014/15 to 2019/20, a combination of complex shocks hit. They brought a major increase in consumption poverty and a stagnation in the A–F multidimensional poverty index. Our application of the FOD approach reinforces this insight considerably. Indeed, our results show that the comparison between 2019/20 and 2014/15 fails determination for most area aggregates. Moreover, for those areas for which it is possible to establish a comparison the probability is close to zero. This is consistent with a situation of stagnation in multidimensional deprivation, one in which two populations are not clearly dominating one another.

In this case as well, a correlation analysis between the A–F and FOD results helps with corroborating the findings. However, when analysing temporal trends, in order to have a way to compare with the temporal FOD probabilities of advancement, we need to first construct a measure of advancement based on the A–F estimates. Thus, we computed the differences in the multidimensional poverty incidence, H, calculated in different years, and related them to the probabilities of advancement computed using the FOD approach. The two measures are certainly different in nature but both provide a measure of advancement (or decline) over time, for different areas.

In Table 7, we see that the correlation coefficients computed between these two measures are generally lower than in the spatial case, but they also show that there is a relationship, and that larger increases/decreases in the multidimensional poverty incidence between one year and another are moderately associated with lower/higher probabilities of advancement, as computed by the FOD procedure. Moreover, the correlation coefficient is the highest (in absolute terms) for the comparison between 2019/20 and 2014/15 (Table 7). This correlation also emerges from a visual examination, see Fig. 5.

Differences in the Alkire–Foster multidimensional poverty incidence (H) (percentage points) and FOD temporal probabilities of advancement over time (%), 2019/20–2014/15. Note: H difference = differences in the Alkire–Foster multidimensional poverty incidence (H) (percentage points); temporal FOD = FOD temporal probabilities of advancement over time (%); Indet. = indeterminate comparison.

We mentioned earlier that, because of the characteristics of FOD comparisons, one or two indicators, following a pattern that diverges from the general trend, may cause indetermination. In particular, in the Mozambican case, and with respect to the comparison between 2019/20 and 2014/15, the deprivation rates for most indicators decreased steadily, as shown in Fig. 3, whereas they increased with respect to water and, especially, to durable goods. To analyse if this latter indicator was behind the mostly indeterminate 2019/20–2014/15 comparisons, we repeated the FOD temporal analysis without considering the durable goods indicator. The results are shown in Table 8.

It appears that the estimated probabilities of advancement in this case increase for most areas, and fewer comparisons result as indeterminate. This aligns with conclusions by Egger et al. (2023), and this helps understanding better the reasons behind the indeterminacy of many temporal FOD comparisons. However, not considering households’ ownership of durable goods in the framework of a multidimensional poverty analysis does not seem to be a particularly relevant/realistic case, given the important role played by these goods in buffering against shocks, especially during crises.Footnote 17

Robustness checks using census data

To check robustness, we apply the FOD method to alternative data sources, namely all the existing census data for Mozambique performed after the end of the conflict in 1992. They include the population census data for 1997, 2007, and 2017.Footnote 18 As done for the household budget survey data, we assess multidimensional poverty, applying the spatial and temporal FOD approach at the national, urban–rural, regional, regional-urban–rural, and provincial levels.

INE conducts the Mozambican censuses (Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação) every 10 years. They cover a wide variety of topics, including economic activity, education, births and mortality, housing, and durable goods. However, they do not include information on consumption and expenditures, which prevents the computation of consumption poverty measures. Nevertheless, it is possible to compute a variety of multidimensional poverty indices given the relatively broad availability of welfare-related indicators. Moreover, the wide coverage of the censuses allows for micro-level estimations, although some variables need adjustment for adequate comparison among the years (INE 1999, 2019, 2023). Using the censuses, we consider the same six welfare indicators as in previous sections.Footnote 19

We introduce the A–F multidimensional poverty incidence first. Results are shown in Table 9.Footnote 20 They show that the multidimensional poverty incidence went from about 87% to about 77% during 1997–2007, decreasing to about 48% in 2017. In 1997, the incidence of multidimensional poverty was overall very high exceeding 75% in every province except Maputo Province and Maputo City. In 2007, improvements occurred in all provinces, especially in Gaza and Maputo Province, while in 2017 the decrease in the incidence of multidimensional poverty was more marked and more broad based, exceeding 30 percentage points in Cabo Delgado, Tete, Manica, and Sofala, and 40 percentage points in Inhambane and Gaza. Yet, it remained high in some areas of the north and centre of the country, being close to or exceeding 60% in Cabo Delgado, Niassa, Nampula, and Zambezia. These insights are broadly consistent with the figures displayed in Table 1.

Next, we turn to the spatial and temporal FOD results (Tables 10 and 11). Table 10 presents area rankings for different spatial aggregates. Here as well, we obtain the spatial FOD results using bootstrap methods to compare different area aggregates based on the net probability of domination. The conclusions from the census-based ranking largely confirm the general trends and spatial divide discussed above. A marked division between the south (especially Maputo City, Maputo Province, and Gaza) and urban areas, on the one side, and the rest of the country, on the other, is evident.

This emerges even more clearly when we compare the southern region and the urban areas to northern provinces (Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula) and to the poorest provinces of the centre (Zambezia, Tete). This split is consistent over the years, and most area aggregates do not change their ranking or do so by only ± 1- ± 2 positions. Once more, the biggest improvement over the period 1997–2017 is for the rural south. It is of particular interest that Cabo Delgado seemed to be on a positive poverty reduction trend until 2017, which then halted from the beginning of the armed insurgency towards the end of the same year.

In this case as well, the correlation between A–F and spatial FOD results is very high, with the standard correlation coefficients and the Spearman’s and Kendall's rank correlation coefficients all well above 0.90 (in absolute terms, not shown).

We also computed the FOD spatial results breaking down each province into urban and rural areas (results not shown but available upon request), which allow for a more detailed understanding of the interaction between the urban–rural divide and the differences in welfare occurring at the provincial level. In broad terms, the recurring pattern over the years seems to be that of the urban area of every province ranking above the national average. This is true also for those provinces ranked at the bottom of the rankings, indicating a strong divide between the rural and urban areas, even within the poorer provinces themselves.

Only the rural areas of Maputo Province and Gaza rank above the national aggregate, and above some of the poorer provinces’ urban areas. This depends also on the way urban and rural areas are classified. Indeed, the classification of many recently urbanised areas in Maputo Province continues to be ‘rural’, though they have some evident urban characteristics. At the bottom of the list, we find, as expected, the rural areas of the five poorest provinces shown in Table 10—that is, Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula, Zambezia, and Tete.

Table 11 reports the temporal net FOD comparisons between 1997, 2007, and 2017 using the same welfare indicators described above. The results in Table 11 reflect the probability of advancement between the years considered. The last two columns highlight that there is a very high probability that 2017 dominates both 1997 and 2007 for virtually all area aggregates. In particular, the probability of advancement is equal or very close to 100% at national and urban–rural level for both 1997–2017 and 2007–17. This reflects clear, evident, improvement on average in every indicator in almost every spatial aggregate, including the poorest provinces, for the two periods.

As discussed, it is uncommon when applying the FOD technique to obtain results as clear as those just presented. However, in the context of Mozambique they do appear realistic. As discussed in introduction, in 1997, the year of the first census considered in this study, Mozambique had just emerged from a 17-year-long conflict; then, the country experienced about 20 years of fast economic growth and improvements in household welfare.

The shocks faced by the country starting from 2015 significantly deteriorated household consumption levels and brought a fast increase in the consumption poverty rate, which continued after the time the census data were collected (August 2017). Indeed, the two major cyclones Idai and Kenneth only hit the country in 2019, the armed insurgency in Cabo Delgado only started to escalate in late 2017, and the COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020.

In sum, our results using census data are in line with those using the household budget surveys. Multidimensional deprivation improved up to 2014/15 (see Table 6) and in 2017 the multidimensional poverty situation was in all likelihood much better than in 2007 and in 1997 (see Table 11). At the same time, gathered evidence shows that this improvement started to decelerate after 2015 and halted in later years, as shown in Table 6 and consistent with Egger et al. (2023), employing data up to 2018. In the case of FOD analyses, the indeterminate results with respect to the probability of advancement likely relate to regression or stagnation in a single indicator (ownership of durable goods). At the same time, it is reassuring that this stagnation in the reduction in multidimensional deprivation corresponds with results from the A–F analyses available.

Summary and discussion

A series of detailed and rich poverty assessments is available for Mozambique based on the existing household budget surveys. They have provided reviews of the evolution of both consumption and multidimensional poverty at the national and sub-national levels. With respect to multidimensional poverty, evaluations are available from 2014/15, using the popular A–F method. In this study, we applied an alternative method based on FOD to (i) assess multidimensional poverty over the entire 1996/97–2019/20 period and (ii) test the robustness/coherence of both the consumption and the multidimensional poverty results obtained using the A–F approach.

Our headline result is that our findings confirm the poverty trends identified in the national poverty assessments and other studies. This is so even though the underlying method is different. The FOD does not rely on a set of weights for the welfare indicators, it does not compute a synthetic welfare index, and it is much stricter when assessing domination of one distribution of welfare attributes over another. In this sense, the Mozambican poverty experience is now on much firmer analytical ground.

From the spatial FOD analysis, it emerges that Maputo City has not only always dominated all other areas, as expected, but also Maputo Province progressively has become the second best province in terms of net domination probability. This improvement in ranking is one of the few exceptions recorded. We mentioned in the introduction how this is likely the result of an ongoing diversification of the economy in the southern region, accompanied by a rapid development of the service sector, the links with South Africa, the growth of the tourism sector, the creation of special economic zones, and the increased availability of publicly provided services in the region, among other factors.

Otherwise, our results show that the rankings obtained from the spatial FOD analysis are very stable over time. Both between 1996/97 and 2019/20, and between 2014/15 and 2019/20, most area aggregates only changed their position by one or two positions. The areas that improved the most are Maputo Province and the province of Tete, together with the rural areas of the southern region. On the other hand, the national average worsened its relative ranking markedly, decreasing by five positions. Among the lowest-ranked areas, we found the central region, the northern region, the provinces of Cabo Delgado, Nampula, Niassa, and Zambezia, and the rural areas at national level and in the northern and central regions.

Not only do these areas lie at the bottom of the ranking in all years, they also register almost no changes between one survey and the other. Indeed, these are the areas where the main economic activity has remained agriculture, in particular low-productivity, subsistence agriculture, characterised by small plots (less than one hectare on average) cultivated mostly without employing improved seeds, credit, fertilisers, or modern tools. Additionally, these are also the most populated and least urbanised areas of the country, meaning that the provision of much-needed public services is further complicated by the lack of infrastructure and by the ever-increasing numbers of potential users.

We also performed a temporal FOD analysis. Our estimates confirm, with a high degree of confidence that the welfare situation consistently improved in Mozambique over time. In particular, the comparisons between the 2014/15 surveys and the preceding ones show high probabilities of advancement for most areas. A similar degree of temporal domination emerges when comparing the 2019/20 survey with the 1996/97, 2002/03 and 2008/09 surveys for most areas. Conversely, when we compare 2019/20 with 2014/15, comparisons are indeterminate for virtually all areas.

This entails that it is not possible to state if multidimensional deprivation improved or not between the two latest surveys. Indeed, for those areas for which it was possible to establish a comparison, the probability is very low and close to zero. This, as argued, is likely due to regression in a single indicator or two, especially given that the safe water indicator stagnated and the durable goods indicator worsened at the national level. However, this analysis points to more broad-based stagnation in terms of welfare and general deprivation, at any level, and it confirms the findings from the A–F multidimensional poverty calculations.

When we use the 1997, 2007, and 2017 census data as a basis for our multidimensional poverty estimations, we confirm that a marked division is evident between the south and urban areas, on the one side, and the rest of the country on the other. This split is consistent over the years, and also in this case most area aggregates do not change their ranking, or do so by only a few positions. Over time, we find a very high probability that 2017 dominates both 1997 and 2007 in terms of multidimensional deprivation for virtually all area aggregates. Once more, this is clear evidence of improvement on average in every indicator in almost every spatial aggregate, including the poorest provinces, between 1997 and 2017 and between 2007 and 17.

While economic shocks started to hit already in 2015—which led to deteriorating household consumption levels and an increasing consumption poverty rate—the compounding effect of the shocks was building up at the time the census data were collected (August 2017). Indeed, the two major cyclones Idai and Kenneth only hit the country in 2019, the armed insurgency in Cabo Delgado only started to escalate in late 2017, and the COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020.

We aimed from the outset at addressing with our FOD approach some of the analytical limitations inherent to the widely-applied and popular A–F method. It is reassuring that the two alternative methods pursued here arrive at consistent results. This is so when they confirm expected trends, when they highlight nuances in the results, or when they point to lack of advancement. Moreover, the FOD by being stricter puts previous results on a stronger analytical foundation.

Nonetheless, the proposed FOD methodology also has a number of limitations, which may make its more widespread implementation in other multidimensional deprivation applications less attractive. First, the FOD approach is more computationally intensive than the A–F. This implies that the number of welfare indicators being included in the analysis should preferably not go beyond six or seven. This is because the number of comparisons being made can easily become difficult to manage. In addition, the risk of obtaining progressively more indeterminate comparisons is likely to soar when more indicators are considered, because the likelihood that one or two indicators may follow a different path from the majority increases. This makes it difficult, for example, to employ the FOD method to evaluate multidimensional poverty using the standard set of indicators included in the Global MPI. This measure is based on 10 indicators (nutrition, child mortality, years of schooling, school attendance, cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity, housing, assets), which would be too many for the FOD method to give meaningful results. Conversely, it would be entirely possible to make use of the FOD method to check the robustness of the World Bank’s MPM results in different contexts, given that it only considers six well-being indicators, and this exercise certainly lies among our next research objectives.

A final drawback of the FOD approach is the difficulty for the analyst to identify the source of indeterminacy of the comparisons when this issue arises. In our study, it was relatively straightforward to identify the main source of indeterminacy with respect to temporal comparisons, given that we only had one or two indicators, out of six, following a different trend. However, this may prove more problematic in case the indicators follow many different temporal or spatial trends, or in case many sub-populations are compared. As mentioned above, the FOD by being stricter puts results on a stronger analytical foundation. At the same time, the strictness of the FOD criteria may become a weakness when deprivation trends become more intricate.

Conclusions