Abstract

We investigate the problem of deciding between trusting and monitoring, and how this decision affects subsequent behavior, using a laboratory experiment where subjects choose between the Ultimatum and the Yes–No Game. Despite the similarity of the two games in Ultimatum Games responders monitor the allocation proposal, while in Yes–No games responders react without monitoring, i.e. have to rely on trust. We permit either the proposer or responder to make the game choice and analyze how both roles choose between trusting and monitoring, what the ensuing effects of their choices are, and how they vary depending on who has chosen the game. We, also, experimentally vary the cost of monitoring and the responder’s conflict payoff. Since monitoring is usually costly, the amount to share in Yes–No Games (YNG) can exceed that in Ultimatum Games (UG). Regarding the conflict payoff, it can be positive or negative with the former rendering Yes–No interaction a social dilemma. According to our results, proposers (responders) opt for trusting significantly more (less) often than for monitoring. Average offers are higher in Ultimatum than in Yes–No games, but neither UG nor YNG offers depend on who has chosen between games.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Frey (1993) stresses the rivalry between trust and loyalty in shaping work effort.

An example of the latter case is the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), in Vienna, which monitors the compliance of many member countries of the Non-Proliferation Treaty for Nuclear Weapons (NTP). Since nuclear energy provision produces uranium in random amounts, underreporting of uranium is discouraged by randomly inspecting nuclear power plants. By monitoring one wants to limit the risk of setting aside uranium for nuclear weapons. How to randomly inspect and prevent underreporting of uranium amounts is far from obvious (see Avenhaus et al. 1996).

As not monitoring allows for “moral wiggle room” which often is exploited (see Dana et al. 2007).

Some determinants which have been looked at are: individual autonomy (Langfred, 2004), view of one’s versus other’s trustworthiness (Ferrin et al. 2007), ongoing (long-term) teams (De Jong and Elfring, 2010), trust in team members versus trust in supervisors (Bijlsma-Frankema et al. 2008), the role of trust in organizational setting (Dirks and Ferrin 2001; Gächter and Falk (2002).

See Malhotra (2004) for a general discussion of differing perspectives of trustors and trusted parties in traditional trust games.

In corporate governance, employers are usually responsible for institutional rules, and are represented by responders in our setup. Proposers, in our setup, represent employees, who may shirk, concisely underperform, steal, etc., and thereby lower the amount to be shared.

In repeated interaction with more feedback, it can make sense to study whether and how trust can be repaired after its violation, for example, by apologizing or attributing the violation to some external cause (see, for instance, Kim et al. 2006).

What is ruled out is, for instance, rejecting meager as well as overgenerous offers (see Güth and Kocher 2014).

Proposer participants, who choose YNG, do not “trust” but only the institution where “trust” is needed.

There may exist other equilibrium outcomes with \(\delta^{*} = 0\) and offers y in the range \(0 \le \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{y} < d\) for d > 0.

Y’s gift would be acceptance, δ = 1, and X’s gift a decent offer.

Initially, allowing one of the interacting parties to opt for an institution is similar to principal agent theory, where usually principals are supposed to offer a menu of employment contracts allowing agents to choose one of them and thereby reveal their types. In case of commercial enterprises with many employees it seems natural that the principal, i.e. the employer, employs screening devices. But it is also possible that an agent applies screening: a very talented singular agent with an attractive outside option may confront the principal, for instance, with a menu of acceptable employment conditions, all inducing the agent not to choose the outside option. Similarly, one can easily imagine for our setup circumstances rendering it reasonable that the proposer, respectively, the responder, confronts a menu of institutional options and thereby may reveal the own type. Of course, when appealing to commercial firms the case of proposers making the institutional choice as well as proposing how to share the pie seems more natural.

Table 9 (in Appendix B) provides more details about offers, separately for treatments and rounds.

Table 10 (in Appendix B) presents more detailed information on YNG acceptance rates.

When participants are aware of the institutional alternative, behavior might depend not only on the given institution but also on its (foregone) alternative chosen what is captured by random selection of one institution, UG or YNG.

The predominance of trusting might erode when providing feedback information which, in turn, might affect the fairness of YNG offers especially for positive cost of monitoring (c > 0). So far our conclusions inform on initial and intuitive tendencies on how to resolve the conflict between trusting, when doubting trustworthiness, and costly monitoring.

References

Audretsch DB, Thurik AR (2000) Capitalism and democracy in the 21st Century: from the managed to the entrepreneurial economy. J Evol Econ 10(1):17–34

Audretsch DB, Thurik AR (2001) What is new about the new economy: sources of growth in the managed and entrepreneurial economies. Ind Corp Change 10:267–315

Avenhaus R (2004) Application of inspection games. Math Model Anal 9(3):179–192

Avenhaus R, Canty M, Kilgour DM, Von Stengel B, Zamir S (1996) Inspection games in arms control. Eur J Oper Res 90(3):383–394

Benabou R, Tirole J (2003) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Rev Econ Stud 70:489–520

Berg J, Dickhaut J, McCabe R (1995) Trust, reciprocity and social history. Games Econ Behav 10(1):122–142

Bijlsma-Frankema K, de Jong B, van de Bunt G (2008) Heed, a missing link between trust, monitoring and performance in knowledge-intensive teams. Int J Hum Resour Manag 19(1):19–40

Bowles S, Polania-Reyes S (2012) Economic incentives and social preferences: substitutes or complements? J Econ Lit 50(2):368–425

Boxall P (1996) The strategic HRM debate and the resource-based view of the firm. HRM J 6(3):59–75

Calvo GA, Wellisz S (1978) Supervision, loss of control, and the optimum size of the firm. J Polit Econ 86:943–952

Cooper DJ, Kagel JH (2016) Other-regarding preferences: a selective survey of experimental results. In: Kagel JH, Roth AE (eds) The handbook of experimental economics, vol 2. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Dana J, Weber RA, Kuang JX (2007) Exploiting moral wiggle room: experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ Theor 33(1):67–80

De Jong BA, Elfring T (2010) How does trust affect the performance of ongoing teams? The mediating role of reflexivity, monitoring, and effort. Acad Manag J 53(3):535–549

De Kok J, Uhlaner LM (2001) Organization context and human resource management in the small firm. Small Bus Econ 17(4):273–291

Dickinson D, Villeval MC (2008) Does monitoring decrease work effort? The complementarity between agency and crowding-out theories. Games Econ Behav 63(1):56–76

Dirks KT, Ferrin DL (2001) The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ Sci 12(4):450–467

Falk A, Kosfeld M (2006) The hidden cost of control. Am Econ Rev 96:1611–1630

Falk A, Gächter S, Kovacs J (1999) Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives in a repeated game with incomplete contracts. J Econ Psychol 20:251–284

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Econ 26(2):301–325

Ferrin DL, Bligh MC, Kohles JC (2007) Can I trust you to trust me? A theory of trust, monitoring, and cooperation in interpersonal and intergroup relationships. Group Organ Manag 32(4):465–499

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Frey B (1993) Does monitoring increase work effort? The rivalry between trust and loyalty. Econ Inq 31:663–670

Fullerton D, Metcalf GE (2002) Tax incidence. Handbook of public economics, Elsevier

Gächter S, Falk A (2002) Work motivation, institutions, and performance. In: Zwick R, Rapoport A (eds) Experimental business research. Kluwer, Boston, pp 351–372

Greiner B (2015) Subject pool recruitment procedure: organizing experiments with ORSEE. J Econ Sci Assoc 1(1):114–125

Güth W, Kocher MG (2014) More than thirty years of ultimatum bargaining experiments: motives, variations, and a survey of the recent literature. J Econ Behav Organ 108:396–409

Halac M, Prat A (2016) Managerial attention and worker performance. Am Econ Rev 106(10):3104–3132

Hendrikse G, Hippmann P, Windsperger J (2015) Trust, transaction costs and contractual incompleteness in franchising. Small Bus Econ 44(4):867–888

Kim PH, Dirks KT, Cooper CD, Ferrin DL (2006) When more blame is better than less: the implications of internal versus external attributions for the repair of trust after a competence-versus integrity-based trust violation. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 99(1):49–65

Langfred CW (2004) Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Acad Manag J 47(3):385–399

Lewicki RJ, Tomlinson EC, Gillespie N (2006) Models of interpersonal trust development: theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. J Manag 32(6):991–1022

Malhotra D (2004) Trust and reciprocity decisions: the differing perspectives of trustors and trusted parties. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 94(2):61–73

Nagin D, Rebitzer J, Sanders S, Taylor L (2002) Monitoring, motivation, and management: the determinants of opportunistic behavior in a field experiment. Am Econ Rev 92:850–873

Prendergast C (1999) The provision of incentives in firms. J Econ Lit 37(1):7–63

Schweitzer M, Ho T, Zhang X (2016) How monitoring influences trust: a tale of two faces. Manag Sci 64(1):253–270

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the constructive advice of their two anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research project was financed by the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods.

Appendices

Appendix A: Instructions (Treatment 1)

Welcome and thank you for participating in this experiment. You are participating in a study on economic decision making. During the experiment you can, depending on your decisions and on other participants’ decisions, earn considerably more money in addition to the 5 euros for showing up on time. Your answers and your choices will be totally anonymous. The experimenters will not be able to associate your choices and your answers to your name.

During the experiment, you cannot communicate with other participants (otherwise you would be excluded from the experiment) and you should be very careful in reading the instructions that will appear on your screen and will be read out by one of the experimenters. If you have any questions, please raise your hand and an experimenter will come to individually answer your questions.

At the end of the experiment, you will be asked to fill a short questionnaire; afterwards, you will be privately paid.

Participants will be matched into pairs, with one member assigned to role X and the other to role Y. Roles will be assigned randomly. The role assigned and the pair composition will remain constant for the whole experiment. Therefore, you will always interact with the same person, whose identity will not be revealed to you. Similarly, your identity will not be revealed to your partner.

In each pair, X and Y have to decide how to split an amount of money in six scenarios that will be described in detail during the experiment. You will not receive any feedback on previous outcomes between scenarios. Only one of the six scenarios will be randomly selected and actually paid, with each of them being equally probable.

In each scenario, the participants in role X have to choose between two mechanisms: mechanism M and mechanism T.

In mechanism M, X and Y can share a given amount of euros. Role X decides how many euros to keep, and how many euros to offer to Y. Y has to state, before knowing X’s offer an acceptance threshold below which X’s offer will be refused. If Y refuses the offer, X will obtain zero euros and Y will earn or lose two euros depending on the specific scenario. If Y accepts the offer, i.e. when the offered amount to Y is not lower than Y’s acceptance threshold, Y receives the offer and X receives the amount kept.

In mechanism T, X and Y can share a given amount of euros. Role X decides how many euros to keep for, and how many euros to offer to Y. Y has to decide whether to accept any offer (without knowing what the offer is). If Y refuses the offer, X will obtain zero euros and Y will earn or lose two euros depending on the specific scenario. If Y accept, Y receives the offer and X receives the amount kept.

The 6 scenarios differ in Y’s gain or loss of two euros if Y rejects, and the possibly different euro amounts to be split in the two mechanisms. Before X decides on the mechanism, X and Y will, both, be informed on the screen about these parameters.

1.1 Scenario 1

X has to decide if the pair will play mechanism M or mechanism T.

Mechanism M: X and Y can share 19 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep for how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y has to state the acceptance threshold below which he/she will refuse X’s offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will lose 2 euros.

Mechanism T: X and Y can share 19 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep and how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y decides whether to accept or refuse any offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will lose 2 euros.

1.2 Scenario 2

X has to decide if the pair will play mechanism M or mechanism T.

Mechanism M: X and Y can share 19 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep for how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y has to state the acceptance threshold below which he/she will refuse X’s offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will earn 2 euros.

Mechanism T: X and Y can share 19 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep and how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y decides whether to accept or refuse any offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will earn 2 euros.

1.3 Scenario 3

X has to decide if the pair will play mechanism M or mechanism T.

Mechanism M: X and Y can share 17 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep for how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y has to state the acceptance threshold below which he/she will refuse X’s offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will lose 2 euros.

Mechanism T: X and Y can share 21 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep and how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y decides whether to accept or refuse any offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will lose 2 euros.

1.4 Scenario 4

X has to decide if the pair will play mechanism M or mechanism T.

Mechanism M: X and Y can share 17 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep for how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y has to state the acceptance threshold below which he/she will refuse X’s offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will earn 2 euros.

Mechanism T: X and Y can share 21 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep and how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y decides whether to accept or refuse any offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will earn 2 euros.

1.5 Scenario 5

X has to decide if the pair will play mechanism M or mechanism T.

Mechanism M: X and Y can share 15 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep for how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y has to state the acceptance threshold below which he/she will refuse X’s offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will lose 2 euros.

Mechanism T: X and Y can share 23 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep and how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y decides whether to accept or refuse any offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will lose 2 euros.

1.6 Scenario 6

X has to decide if the pair will play mechanism M or mechanism T.

Mechanism M: X and Y can share 15 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep for how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y has to state the acceptance threshold below which he/she will refuse X’s offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will earn 2 euros.

Mechanism T: X and Y can share 23 euros and role X decides how many euros to keep and how many euros to offer to Y. Role Y decides whether to accept or refuse any offer. If X’s offer is refused, X will earn zero euros and Y will earn 2 euros.

[Treatment 2—Scenario order: 5, 6, 3, 4, 1, 2

Treatments 3 and 4—As 1 and 2 but Responder chooses game]

Appendix B: Additional descriptives

See Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14

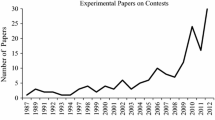

Appendix C: Figure complements

About this article

Cite this article

Angelovski, A., Di Cagno, D., Grieco, D. et al. Trusting versus monitoring: an experiment of endogenous institutional choices. Evolut Inst Econ Rev 16, 329–355 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-019-00126-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-019-00126-4