Abstract

Supporting student wellbeing in schools is increasingly becoming a global priority. However, research and initiatives primarily focus on general wellbeing rather than subject-specific experiences. Given the pervasive levels of mathematics anxiety, negative attitudes, and disengagement in mathematics education, we argue for a more contextualised wellbeing approach. We define ‘mathematical wellbeing’ (MWB) as the fulfilment of values whilst learning mathematics accompanied by positive feelings (e.g., enjoyment) and functioning (e.g., engagement) in the discipline. We report on 3073 New Zealand Year Three to Eight students’ responses to a survey measuring their fulfilment of seven MWB values: accomplishments, cognitions, engagement, meaning, perseverance, positive emotions, and relationships. Students’ MWB was highest for relationships and perseverance and lowest for engagement and positive emotions; MWB declined from Years Three to Eight; females often rated higher MWB than males; school sociodemographic status was mostly not significant, whilst engagement and positive emotions differed across ethnicities. Research implications include understanding target areas to improve diverse students’ experiences and wellbeing in mathematics education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many research studies (e.g., Ashcraft, 2002; Li et al., 2021; Perry, 2004; Way et al., 2020) over several decades continue to show the relationship between negative affect and mathematics teaching and learning. This is evidenced by the lack of improvement concerning students’ attitudes, interests, and engagement in mathematics; underrepresentation of specific groups (e.g., females, minorities, and Indigenous students); and student avoidance of advanced mathematics subjects in secondary school and university (English, 2016; Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015; Watt et al., 2019)—all indicators of pervasive illlbeing in mathematics. Earlier studies (Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015; Larkin & Jorgensen, 2016) highlighted that students often start school feeling positive towards mathematics, so it is likely not the discipline of mathematics per se that creates negative affect but how students experience mathematics in school. Given that students’ mathematical affect (e.g., emotions, interests, attitudes, beliefs) and engagement diminish as they progress from primary to secondary school (Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015; Supter & Sollerman, 2023; Widland et al., 2021), we conjecture that student wellbeing in mathematics education—or ‘mathematical wellbeing’ (MWB) might also decline. Specifically, as students progress through school, many core or ‘ultimate values’ of students are increasingly not being fulfilled in the mathematics classroom, potentially contributing to mathematical anxiety, disengagement, avoidance of mathematics, and mathematical illbeing. For instance, as students advance from primary to middle schooling and then secondary school, they increasingly work independently in mathematics, which potentially clashes with their social values; they increasingly ask, ‘what is the point of learning this?’ thwarting students’ valuing of meaningful experiences; and high stakes assessments in the upper secondary years emphasise failings rather than their successes which challenges students’ valuing of accomplishment. Improving student wellbeing is fast becoming a core aim of school education (UNESCO, 2022; United Nations, n.d.). However, subject-specific explorations of student wellbeing are lacking, with most focusing on wellbeing across all subjects combined.

Given that mathematics is often challenging for many students, we argue for a more contextualised wellbeing approach targeted to individual subject disciplines. A wellbeing focus emphasises students’ strengths while acknowledging the values that are being (un)fulfilled in the learning process. Previous studies (Hill et al., 2021, 2022, 2023; 2024) have examined student wellbeing specific to mathematics education, uncovering seven values (i.e., accomplishment, cognitions, engagement, meaning, perseverance, positive emotions, and relationships) that, when fulfilled support students to feel good, function well, and thus have high MWB. Yet, most of these explorations focus on Australian secondary students and pay little attention to age and demographic differences in MWB. Studies have been undertaken in New Zealand focused on aspects of wellbeing in education or attitudes to learning mathematics (Educational Assessment Research Unit (EARU) & New Zealand Council of Educational Research (NZCER), 2023; Ritchie, 2023). However, it appears that there are limited studies from New Zealand that focus explicitly on MWB. Additionally, international studies with culturally diverse groups of students are also lacking. This paper attends to these gaps in the research field by examining MWB for diverse New Zealand students across primary, middle, and lower secondary schools.

Theoretical Framing and Literature Review

This section first explores the underpinning theoretical framework and key concepts. Second, given the limited studies exploring demographic differences in MWB, we review related studies reporting on students’ emotions, affect, and learning experiences in mathematics across age, gender, and socioeconomic groups.

A Value Fulfilment Framework of MWB

Values act as the blueprint for our wellbeing because values represent what is important; they guide our decisions, judgments, and actions and serve as benchmarks to assess how well our lives (and educational experiences) are going (Halstead, 1996; Schwartz, 2012; Tiberius, 2018). When values are fulfilled, individuals generally feel happy (i.e., hedonic wellbeing) and function optimally (i.e., eudemonic wellbeing) (Huppert & So, 2013). We define wellbeing according to value fulfilment theory (Tiberius, 2018), which posits that "our lives go well to the extent that we pursue and fulfil our appropriate values… your life goes badly to the degree that you live a life that has little value fulfillment" (Tiberius, 2018, p. 34). This theory provides insights into enhancing wellbeing by identifying students’ values and suggesting actions for teachers and students, such as pedagogical approaches, classroom atmosphere, and class positioning, to facilitate the fulfilment of these values. Tiberius described core or ‘ultimate values’(UVs) as values valued for their own sake, generally consistent across individuals and contexts (e.g., environments, cultures), and most predictive of wellbeing. Close relationships, meaningful experiences, or happiness are examples of UVs (Seligman, 2011; Tiberius, 2018). Underneath UVs are instrumental values (IVs). IVs are valued to achieve higher UVs, and IVs can differ widely across individuals and contexts (Tiberius, 2018). Examples of IVs are helping others, friendships, or group work, and these IVs are valued to achieve close relationships (a UV).

Applied to mathematics education, we define MWB as the realisation of values within the mathematics learning process (Hill et al., 2022). Fulfilling these values fosters happiness and optimal functioning in the subject (Huppert & So, 2013; Tiberius, 2018). For example, a mathematics student who values peer support will likely seek collaborative learning opportunities in the classroom, enjoy and engage more, and thus have higher MWB when such opportunities are provided. The MWB framework used in this study was developed theoretically through a scoping review and then empirically confirmed with primary and secondary students (Hill et al., 2021, 2022, 2023). Across these studies, Hill and colleagues identified seven UVs that, when fulfilled, foster students’ MWB: Accomplishments, cognitions, engagement, meaning, perseverance, positive emotions, and relationships (for descriptions of these, see Table 1). These UVs were derived from other wellbeing frameworks including Seligman’s PERMA model (Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment) (Seligman, 2011), Kern’s et al.'s EPOCH model (Engagement, Perseverance, Optimism, Connectedness, Happiness) (Kern et al., 2016), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) framework of student wellbeing in schools (OECD, 2015), and an earlier MWB model (Clarkson et al., 2010). The hierarchy of these UVs can differ across different groups of students (e.g., country, culture, gender) (Hill et al., 2022; 2023). For example, students from collectivist cultures (e.g., Pacific peoples) may prioritise relationships more than those from individualist cultures (e.g., Western Europeans).

Wellbeing models and frameworks (e.g., PERMA, EPOCH, MWB) are reductionist; however, wellbeing is highly complex and ephemeral. A plus side of simplified wellbeing frameworks (like those mentioned above) is that teachers and schools can relate to and understand these; they also provide tangible and potentially measurable entities (Kern, 2021). Values are an excellent place to start because they signpost what is most important, and we can measure the extent to which students experience or act on these values. Our study incorporates a survey (see Table 3) to measure students’ enacted values in mathematics education to quantify students’ value fulfilment – that is, their MWB.

Age and Demographic Differences in Student Affect and MWB

To our knowledge, no studies have examined changes in student MWB across primary to middle years and early secondary school. However, the increase in anxieties, negative emotions, and attitudes over this transition (e.g., Widland et al., 2021) would suggest that students’ MWB would also decrease. As students progress through schooling, the classroom’s social and physical structures, teaching, and pedagogies significantly change. Students move from discrete self-contained to more heterogeneous classrooms; learning becomes less scaffolded; textbook use increases; mathematics learning transitions from concrete to more abstract, whilst collaborative pedagogies are often replaced by independent working arrangements (Banilower et al., 2013; Prendergast et al., 2019; Wilkie, 2013). These shifts are often accompanied by a negative slide in students’ feelings, attitudes, and engagement in mathematics (Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015; Widland et al., 2021). The primary to middle and secondary school transition (i.e., middle school period) often presents the most significant challenges for students, which can be more pronounced in the mathematics classroom (Bicknell & Hunter, 2012; Prendergast et al., 2019). Students often begin school feeling positive towards mathematics and finish the primary years with a similar positive disposition (Caygill & Kirkham, 2008; Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015). However, by the time students reach middle and secondary school, many students experience a detrimental shift in their affect and engagement (Attard, 2011; Supter & Sollerman, 2023). For example, a cross-sectional study noted that New Zealand students’ confidence with and attitudes towards mathematics decreased, and mathematics anxiety increased during the transition to secondary school (Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015). The 2015 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) study noted that across the OECD countries, 81% of upper primary (Year 4) students liked or very much liked mathematics, and 21% did not, which in Year 8 shifted to 61% who liked or very much liked mathematics, and 38% did not (Mullis et al., 2016). Likewise, students’ enjoyment, interest, and confidence in mathematics significantly declined from Year 4 to Year 8 (Supter & Sollerman, 2023). These results are paralleled in the most recent National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (NMSSA) undertaken in New Zealand in 2022 (EARU & NZCER, 2023). Similarly, Attard (2010) noted that students reported pedagogical and curricular changes over the transition from primary to secondary. For example, a faster-paced curriculum, fewer teacher-student interactions, more assessments, less ‘hands-on’, and more independent than collaborative working—all these changes negatively impacted students’ perceptions of and engagement towards mathematics (Attard, 2010). Deiso and Fraser (2019) also reported a deterioration in students’ attitudes and enjoyment towards mathematics over the primary to middle years and secondary school transition.

Limited studies have examined gender differences in students’ MWB. Gender is defined here as the socially constructed characteristics of boys and girls (World Health Organization, n.d.). Given that extant literature attests to gender differences in mathematical affect and values (e.g., Deiso & Fraser, 2019; Hill & Hunter, 2023), we expect a similar gender pattern in students’ MWB, which we investigate in this study. For instance, various studies purport that female students are more anxious despite having greater motivations to succeed in mathematics (Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015; Penty & Huebeck, 2013); male students held more positive self-concepts, intrinsic motivation, and had higher performance expectations than females (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2004; Watt et al., 2012); and females perceived mathematics to be less useful for their lives than males (Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015). Supter and Sollerman (2023) reported that in Year Four, females liked and enjoyed mathematics less and were less confident than males, and by Year Eight, this gender affect divide increased further. Similarly, the NMSSA study in New Zealand has found that boys scored higher on the attitude to mathematics scale (EARU & NZCER, 2023). Several studies asserted that females espoused more socially related values in mathematics, such as family support, peer collaboration, and respectful classroom relationships (e.g., Hill & Hunter, 2023; Wong, 1995), yet simultaneously rated receiving less social support, undertook less group work, and felt less involved than males in the mathematics classroom (Eccles, 2011; Samuelsson & Samuelsson, 2016). These findings suggest that female students’ socially directed values might be less likely to be fulfilled in the mathematics classroom than males.

In many countries, including New Zealand, there is a correlation between low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds and ethnicity, which is often reflected in indigenous and migrant groups being from low SES communities. Strand (2013) indicated that students from low SES groupings may experience disadvantages due to lower teacher expectations. Additionally, Guo et al. (2015) showed that higher SES students were more likely to hold positive motivations, have higher mathematics achievement and aspirations, and perceive mathematics as more useful. Grootenboer and Marshman (2015) found that students from higher SES groups tended to hold more positive mathematics attitudes and were less anxious. However, interestingly, in the New Zealand context, results from the recent NMSSA study report differ from these findings, with Pacific students scoring higher on the attitude to mathematics scale than non-Pacific students and students from low decile schools also scoring higher in their attitude to mathematics than those from mid to high decile schools (EARU & NZCER, 2023). In New Zealand, school decile has been used as a proxy for the socio-economic status of school catchment areas with lower decile schools in lower socio-economic neighbourhoods. In summary, although these studies have some differing results, it is clear that age, gender, and SES impact students’ experiences and feelings towards mathematics education. In this study, we extend this to explicitly explore differences in MWB across groups of students.

The Current Study

This study examines the extent to which diverse students in New Zealand are thriving in mathematics education. Specifically, we respond to the following research questions:

-

(1)

To what extent are primary and middle-year New Zealand students experiencing the seven MWB ultimate values (UVs: accomplishments, cognition, engagement, meaning, perseverance, positive emotions, and relationships)?

-

(2)

Do primary and middle years students’ experiences of these seven UVs differ across student year levels and demographic groups?

Research Design and Methods

Participants

Participants included 3073 Years Three to Year Eight students (aged between seven and thirteen years) attending one of 35 state schools across New Zealand. Schools covered urban, regional, and rural areas. This included 29 primary schools (Year One to Year Six), one full primary school (Year One to Year Eight students), two Intermediate schools (Year Seven to Year Eight) and three secondary schools (Year Seven to Year 13). All of the schools were involved in a professional learning and development initiative funded by the New Zealand Ministry of Education focused on raising achievement in mathematics of diverse groups of students (see Hunter & Hunter, 2023; Hunter et al., 2018). This, in part, accounts for the higher proportion of students from low socio-economic and diverse cultural backgrounds in the sample. Student demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 2. All schools were invited to participate in the study by an email invitation to the school leadership. Following consent from the school principal, an opportunity was provided for the parents and students to opt out of the study. The Ethics committee approved the overall study at the second author’s institution.

Data Collection

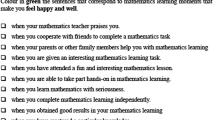

The students completed a Qualtrics survey during regular class time sometime between March 2020 and March 2021. Here, we report on students’ responses to 17 Likert questions measuring the degree of value fulfilment (i.e., values that are enacted or experienced) for each of the seven UVs, with the survey questions summarised in Table 3. Children can struggle to reflect on and rate their values (Collins et al., 2017; Döring et al., 2010). Thus, surveys measuring children’s values are often worded so that children compare each survey item to their own lives and context. For example, the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ; Döring et al., 2010) asks students to rate the importance of values by responding to the question “How much like you is this person” (p. 628) and using a six-point scale; the children rate the level of similarity as a proxy for the degree of importance (or valuing). Thus, we adopt similar wording in our MWB survey, which measures students’ enacted values or value fulfilment.

Given that our seven UVs were deductively derived from other wellbeing models, our MWB survey mostly adapted the wording from existing wellbeing surveys (e.g., Butler & Kern, 2016; Kern et al., 2016). For instance, Kern et al. (2016) EPOCH survey (Engagement Perseverance, Optimism, Connectedness, Happiness) measuring adolescent wellbeing included the survey item I am a hard worker (measuring perseverance). To be relevant to MWB, we adapted this to: I work hard at my maths learning; likewise, I get completely absorbed in what I am doing (measuring engagement) was adapted to When I am doing maths, I get completely absorbed in what I am doing. Using a digital device, students responded to the randomised survey questions using a five-point scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) up to five (strongly agree).

The confirmatory factor analysis results provided acceptable data model fit for this New Zealand sample, χ2 = 377.29, df = 98, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.033 (0.029, 0.036), SRMR = 0.022. Factor loadings (λ) ranged from 0.59 to 0.81.

The seven UVs also demonstrated a high level of internal consistency, confirming the reliability of the survey instrument (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Data Analysis

The survey responses were imported into SPSS (Version 29) for statistical analysis. Pearson correlations were computed between the seven UVs to determine the relationship between different UVs.

Responding to our first research question, we examined the overall mean differences across the seven UVs, with one-way repeated measures ANOVA (using Greenhouse–Geisser corrections if needed), determining which MWB values were rated significantly higher than others across the whole sample. Measures of effect size were calculated using partial eta-squared (η2). We calculated an overall MWB score by averaging the scores across the seven UVs. While we include students’ overall MWB in Figs. 1 and 2, we did not statistically compare students’ overall MWB across groups of students because single-score wellbeing measures lack the specificity needed for change; they also disregard the multidimensional nature of wellbeing (Kern et al., 2016).

Mean value ratings across the seven UVs across the whole sample. Note. UVs are ordered from the highest (left box) to the lowest (right box) mean ratings. Rel = Relationships, Pers = perseverance, Acc = Accomplishment, Mean = Meaning, Cogs = Cognitions, PosE = Positive emotions, Eng = Engagement, Total MWB = mean score across the seven UVs

To answer research question two, we used a series of seven one-way multifactorial ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections to investigate if each UV was rated significantly higher or lower by certain groups of students (i.e., year level, gender, ethnicity, SES). The UVs were used as the dependent variables, and eight-year levels, two genders, eight ethnic groups, and three school SES levels as fixed factors. Levene’s tests confirmed the homogeneity of variance for all ANOVA tests. All main effects were examined. Two-way interactions between year level and gender were also explored given the widely reported gender and year level differences in mathematical affect (e.g., Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015), and to determine if any gender differences in MWB were more pronounced for middle-year students than primary students.

Results

As shown in Table 4, the seven UVs were all positively related to each other, with the strongest correlations observed between cognitions and perseverance (r = 0.64) and between positive emotions and engagement (r = 0.64). Overall, MWB correlated most strongly with positive emotions (r = 0.82). Relationships had the weakest correlations with the other UVs (0.38 < r < 0.44) and with overall MWB (r = 0.64).

Across all 3073 students the means scores differed significantly across the seven UVs, F(6.35, 19,347.9) = 88.57, p < 0.01). As shown in Fig. 1, the UV relationships had the highest mean rating (M = 4.04, SD = 0.9), followed by perseverance (M = 4.01, SD = 0.87), accomplishments (M = 3.98, SD = 0.96), meaning (M = 3.96, SD = 0.98), cognitions (M = 3.9, SD = 0.96), positive emotions (M = 3.85, SD = 1.02), and engagement (M = 3.77, SD = 0.99). Figure 1 also shows engagement and positive emotions skewed towards lower ratings compared to the other UVs. Pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni corrections indicated that the three highest-rated UVs (i.e., relationships, perseverance, and accomplishments) were each rated significantly higher (all p < 0.01) than cognitions, engagement, and positive emotions. The UV meaning was rated significantly lower than the top two (i.e., relationships and perseverance) but significantly higher than the remaining UVs (cognitions, positive emotions, and engagement). Cognition was rated significantly higher than only engagement.

Group differences across the UVs were also investigated. Table 5 summarises each UV mean value and standard deviation across each demographic group. Main effects for year level were found across each of the MWB values (see Table 6) with small to medium effect sizes, attributed to younger students experiencing each of the UVs significantly more than the older students. Figure 2 shows the steady decline in scores from Years Three to Eight, with the sharpest decline over the primary to middle or secondary school transition (i.e., Years Six to Seven, average MD = 0.18 across the UVs). Notably, positive emotions showed the greatest decrease (MD = 0.69) and effect size (η2 = 0.05) from Years Three to Eight, shifting from the second-highest rated MWB value to the second-lowest overall. However, between Years Five and Six and between Years Seven and Eight, students’ mean ratings across each MWB value increased slightly or remained consistent. However, these changes were not significant.

Main effects for gender were found for the UVs accomplishment, meaning, perseverance, and relationships, with females rating these values higher than males (as shown in Table 6). School SES main effects were discovered for perseverance only, with higher mean ratings reported by medium SES schools (i.e., deciles four to six) compared to low SES schools (i.e., deciles one to three). Finally, significant two-way gender x year level interactions were observed for positive emotions, attributed to Year Five and Six males reporting this value higher than females in these year groups.

Main effects were found for ethnicity in relation to the UV engagement (Table 6). Indian/Pakistani students rated engagement significantly higher than Māori, New Zealand European, and Pacific students. Additionally, Māori students rated engagement higher than Pacific students, while Pacific students rated it higher than New Zealand European students.

Similarly, main effects were observed for the UV positive emotions. Asian students rated positive emotions higher than New Zealand European students. Indian/Pakistani students rated it higher than Māori, New Zealand European, and Pacific students, and Pacific students rated it higher than New Zealand Europeans.

Discussion

Across the limited studies exploring student MWB to date, none have explicitly examined demographic differences in student MWB. The current study reports on diverse Year Three to Eight New Zealand students’ MWB. It examines students’ MWB overall and across year levels, genders, and school SES.

Key findings included:

-

1.

Year Three to Eight New Zealand students experienced the highest levels of MWB for the UVs relationships and perseverance and the lowest for engagement and positive emotions.

-

2.

Students’ MWB significantly declined across all the UVs from Year Three to Year Eight, with the sharpest decline over the primary to middle or secondary school transitions and the lowest levels of overall MWB for Year Seven students.

-

3.

Females experienced the UVs accomplishments, meaning, perseverance, and relationships significantly more than males.

-

4.

School SES had minimal impacts on students’ experiences of MWB, with only perseverance experienced significantly more by students from medium than low SES schools.

-

5.

Only the UVs engagement and positive emotions were experienced differently across ethnicities, mainly because Indian and Pakistani students experienced these UVs more, and New Zealand Europeans experienced these UVs less than students from other ethnicities.

New Zealand Students’ Experiences of MWB

Students’ overall MWB was most strongly associated with positive emotions (see Table 4), indicating a strong sense of enjoyment and optimism towards mathematics. The strongest UV correlations were found between cognitions and engagement, suggesting that students are more likely to persevere, work hard, and practice mathematics when they understand their learning and possess relevant mathematical skills and content knowledge. Similarly, positive emotions and engagement showed a high correlation, indicating a synergistic relationship between students’ enjoyment of and interest in mathematics. This aligns with earlier studies showing that enjoyment and interest are highly related (Ainley & Hidi, 2014; Schukajlow, 2015). Similarly, the 2022 NMSSA study found a correlation between student achievement and a positive attitude and confidence towards mathematics as a subject (EARU & NZCER, 2023).

Overall, New Zealand primary and middle-year students experienced the UV relationships and perseverance the most. Thus, these two UVs might be considered strengths enhancing students’ overall MWB. Positive classroom relationships encompass feelings of connectedness, belonging, reciprocity, and respect. Perseverance describes working hard, putting in sustained effort, and practising mathematics. It was encouraging that students rated their relationships so strongly, given that students’ achievement, engagement, attitudes, and enjoyment of mathematics are often predicted by students’ perceptions of their relationship with teachers (Averill, 2012; Hattie, 2008; Riconscente, 2014; Schukajlow et al., 2023). Similarly, strong peer support positively influences students’ mathematical problem-solving skills, achievement, self-concept, and attitudes towards mathematics (Fawcett & Garton, 2005; Tsuei, 2012). Barnes (2021) reports that perseverance has been increasingly paid attention in education in recent years, and in mathematics, this is often related to maintaining engagement in mathematical reasoning. Perseverance is connected to sense-making in mathematics and working to overcome both cognitive and affective difficulties (Barnes, 2019; Morales & DiNapoli, 2018). In this study, students reported high levels of perseverance in mathematics, which was encouraging.

Conversely, engagement and positive emotions were the UVs experienced the least by students, signalling an area of weakness that potentially undermines students’ overall MWB. Engagement encompasses deep interests and focused attention, while positive emotions include feelings like enjoyment, optimism, and happiness in mathematics. We also discovered that positive emotions were more highly associated with students’ overall MWB, indicating that these positive emotions—or lack thereof—had a bigger impact on students’ MWB than the other six UVs. Thus, it was concerning that students experienced positive emotions the least.

Pervasive negative emotions and disengagement in mathematics are global challenges (Mullis et al., 2016; OECD, 2013). For example, across OECD countries, a fifth of Year Four and over two-thirds of Year Eight students report they dislike mathematics (Mullis et al., 2016). Failing to fulfil their valuing of positive emotions may also reflect the prevalence of mathematics anxieties in classrooms worldwide. For example, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) reported that 30% of students internationally felt helpless and stressed when doing mathematics (OECD, 2013). Fulfilling engagement and positive emotions are often complementary; interesting mathematical tasks or pedagogies (i.e., UV engagement) are also often enjoyable (i.e., positive emotions). However, Barnes’s findings (2021) indicated that enjoyment in learning mathematics can be a barrier to student perseverance in mathematical reasoning. Therefore, future research would be helpful to examine the types of classroom pedagogy and practices that both support students to persevere and engage in mathematics while also feeling positive emotions.

We note that while some UVs were experienced more than others, the mean ratings for each UV were still above 3.7 out of 5 (shown in Fig. 1). Similarly, other wellbeing surveys tend to skew towards the positive end, with the midpoint typically set at 3.25 out of 5 (and not 2.5) (e.g., Butler & Kern, 2016). However, the survey still provides valuable information about specific focus areas for pedagogical practices to improve MWB.

Declining MWB as Students Progress Through School

A key finding was the significant decline in students’ MWB as the school year level increased, particularly evident during the transition from primary to middle and lower secondary school. This decline coincides with the typically stressful transition period, during which students encounter significant social, organisational, and academic changes. Of concern, the decline in MWB begins as early as the mid-primary years (as shown in Fig. 2) and potentially even earlier. Therefore, strategies to improve students’ MWB should commence in the early primary years, as by the time students reach secondary school, their MWB may have irreversibly declined. This may be especially true for the UV positive emotions. Figure 2 illustrates that this UV experienced a more significant decline and had a larger effect size than all other UVs. Positive emotions transitioned from being the second-highest rated UV in Year Three (after relationships) to the lowest rated UV by Year Eight—a difference of 0.69 points on the scale, with a corresponding medium effect size. To put this into perspective, a mean difference of 0.7 points on the PERMA profiler wellbeing scale can indicate a difference between a normal and sub-optimal level of flourishing (Butler & Kern, 2016). This aligns with earlier research showing that students often begin primary school with a positive mathematical disposition, yet due to their schooling experience, this mathematical affect shifts to become negative (Attard, 2010; EARU & NZCER, 2023; Grootenboer & Marshman, 2015; Mullis et al., 2016; OECD, 2013). Research studies in international contexts have attributed this decline to factors such as pressure to achieve, overreliance on textbooks, and fewer opportunities for peer collaboration (Attard, 2010; Prendergast et al., 2019; Supter & Sollerman). Future explorations in New Zealand should examine the potential sources of this decline in MWB.

Gender, SES, and Ethnic Differences in Students’ MWB

Surprisingly, gender differences were only significant for female students, who rated the UVs accomplishments, meaning, perseverance, and relationships higher than males. However, these differences demonstrated small effect sizes (see Table 6). Other studies have reported that female students value social aspects of mathematics more than males, aligning with our results (Hill & Hunter, 2023; Wong, 1995). Conversely, earlier studies showed female students experienced more negative emotions and self-concepts, lower interest, enjoyment and performance expectations, and poorer utilitarian beliefs in mathematics than males (EARU & NZCER, 2023; Grootenboer & Marshamn, 2015; Penty & Huebeck, 2013; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2004; Watt et al., 2012). Interestingly, the findings of our study contrast with these results from both the New Zealand-based NMSSA and international settings and indicate that students of different genders in this study had similar levels of MWB. Findings, however, showed that males experienced positive emotions significantly more than females, but only in Years Five and Six. Further research is needed to understand the difference between Years Five and Six and examine the types of classrooms in New Zealand that support students of both genders to have similar levels of MWB.

Similarly, we also observed minimal SES differences in MWB which run counter to earlier research on mathematical affect (Guo et al., 2015; Marshman & Grootenboer). For example, these earlier studies found that students from higher SES backgrounds typically reported higher achievement, more positive attitudes, and enjoyed mathematics more. The current study found only one difference, where UV perseverance was experienced more by students from medium SES schools (deciles 4–6) than in low SES schools (deciles 1–3).

Concerning ethnic differences, only the UVs engagement and positive emotions differed significantly. Students from Indian and Pakistani cultural heritage tended to experience the UVs more than students from other ethnicities and significantly more than students from Māori, New Zealand European, and Pacific cultural heritage. New Zealand European students experience these UVs the least. Further research is necessary to understand these differences; however, potentially, the sources of these differences might be related to cultural norms and how STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects are valued.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has several limitations but also provides avenues for future research. Firstly, we used cross-sectional data; thus, the trajectory of MWB for individual students is unclear. Future studies might use longitudinal designs to provide a more robust view of the changes in student MWB over time. The survey results presented here provide a snapshot of students’ experiences across the seven UVs but cannot provide deeper reasons or explanations for why certain UVs were experienced more or less. Additionally, we acknowledge the diversity of school structures concerning middle-year and lower-secondary schooling formats in New Zealand. This meant that students in this study in the middle years experienced a range of schooling structures, including a full primary school or middle and secondary schools. This has the potential to influence the results concerning schooling transitions. Furthermore, the sample of students was oriented to low socio-economic schools and students from diverse cultural backgrounds, which may have influenced the findings.

Although not reported in this study, the survey design included some free response items. Further research will interrogate the connection between student responses to these items to understand students’ perspectives of the UVs. Importantly, we highlight the need for further research into MWB to gain an understanding of both the differences in the results from this New Zealand study and studies from international contexts and, more importantly, to examine possibilities for the design and implementation of innovative interventions for teacher practices to improve student MWB.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study offers a snapshot of students’ MWB in New Zealand. Our findings indicate that students reported higher levels of MWB for the UVs of relationships and perseverance while reporting lower MWB for engagement and positive emotions. Concerningly, students’ MWB declined from Years Three to Eight, particularly for positive emotions. The findings regarding gender and SES offer an interesting contrast to those reported in international studies. The results of this study will serve as a baseline to measure subsequent changes in students’ MWB as they progress through a mathematics professional development and learning initiative focused on culturally sustaining pedagogy. Additionally, these findings provide educators with valuable insights into areas to focus on regarding pedagogy and practice in mathematics classrooms to potentially enhance students’ experiences and wellbeing in mathematics. For instance, teachers could target the UVs rated lowest by students by incorporating pedagogies and learning experiences to support students in fulfilling their values in the mathematics classroom. This initial exploration into MWB for diverse students in New Zealand schools is an important first step in measuring MWB levels while laying the foundations for investigating strategies to improve students’ MWB.

This work was supported by a Royal Society of New Zealand Rutherford Discovery Fellowship research grant: RDF-MAU1903.

The data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (Julia Hill, hill.j@unimelb.edu.au). However, the data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy.

References

Ainley, M., & Hidi, S. (2014). Interest and enjoyment. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 205–227). Routledge.

Ashcraft, M. H. (2002). Math anxiety: Personal, educational, and cognitive consequences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(5), 181–185.

Attard, C. (2010). Students’ experiences of mathematics during the transition from primary to secondary school. In L. Sparrow, B. Kissane, & C. Hurst (Eds.). Shaping the future of mathematics education: Proceedings of the 33rd annual conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia, (pp. 53–60). MERGA.

Averill, R. (2012). Caring teaching practices in multiethnic mathematics classrooms: Attending to health and wellbeing. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 24(2), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-011-0028-x

Banilower, E. R., Smith, P. S., Weiss, I. R., Malzahn, K. M., Campbell, K. M., & Weis, A. M. (2013). Report of the 2012 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education. Horizon Research Inc. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED548238.

Barnes, A. (2019). Perseverance in mathematical reasoning: The role of children’s conative focus in the productive interplay between cognition and affect. Research in Mathematics Education, 21(3), 271–294.

Barnes, A. (2021). Enjoyment in learning mathematics: Its role as a potential barrier to children’s perseverance in mathematical reasoning. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 106(1), 45–63.

Bicknell, B., & Hunter, R. (2012). School transition from year six to year seven: A focus on mathematics. International Journal for Mathematics Teaching and Learning. https://www.cimt.org.uk/journal/hunter.pdf

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Caygill, R., & Kirkham, S. (2008). TIMSS 2006/07: Trends in Year 5 mathematics achievement 1994 to 2006. New Zealand Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/numeracy/TIMSS-200607/34160/13.

Deieso, D., & Fraser, B. J. (2019). Learning environment, attitudes and anxiety across the transition from primary to secondary school mathematics. Learning Environments Research, 22, 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-018-9261-5

Döring, A. K., Blauensteiner, A., Aryus, K., Drögekamp, L., & Bilsky, W. (2010). Assessing values at an early age: The picture-based value survey for children (PBVS–C). Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(5), 439–448.

Eccles, J. (2011). Gendered educational and occupational choices: Applying eccles et al model of achievement related choices. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411398185

Educational Assessment Research Unit & New Zealand Council of Educational Research. (2023). National monitoring study of student achievement mathematics and statistics contextual findings 2022. Ministry of Education.

English, L. D. (2016). STEM education K–12: Perspectives on integration. International Journal of STEM Education, 3(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-016-0036-1

Fawcett, L. M., & Garton, A. F. (2005). The effect of peer collaboration on children’s problem-solving ability. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(2), 157–169.

Grootenboer, P., & Marshman, M. (2015). Mathematics, affect and learning: Middle school students’ beliefs and attitudes about mathematics education. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-679-9_4

Guo, J., Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., Morin, A. J. S., & Yeung, A. S. (2015). Expectancy-value in mathematics, gender and socioeconomic background as predictors of achievement and aspirations: A multi-cohort study. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.01.008

Halstead, J. M. (1996). Values and values education in schools. In J. Halstead & M. Taylor (Eds.), Values in education and education in values (pp. 3–14). The Falmer Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203973554

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hill, J. L., & Hunter, J. (2023). Examining the mathematics education values of diverse groups of students. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 54(8), 1614–1633. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2023.2184280

Hill, J. L., Kern, M. L., Seah, W. T., & van Driel, J. (2021). Feeling good and functioning well in mathematics education: Exploring students’ conceptions of mathematical wellbeing and values. ECNU Review of Education, 4(2), 349–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120928084

Hill, J. L., Kern, M. L., Seah, W. T., & van Driel, J. (2022). Developing a model of “mathematical wellbeing” through a thematic analysis of the literature. In M. Vollstedt, I. Kontorovich, K. Jones, & D. Sommerhoff (Eds.), Proceedings of the 45th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, (Vol 2, pp. 32–39). PME. https://www.igpme.org/publications/current-proceedings/

Hill J L Kern M L Seah W T & van Driel J (in press) To what extent are students fulfilling their values and thriving in mathematics education? – The case for Victoria, Australia. In Y. Dede, G. Marshall, & P. Clarkson (Eds.), Values and valuing in mathematics education: Moving forward into practice. Springer.

Hill, L., & Seah, W. T. (2023). Student values and wellbeing in mathematics education: Perspectives of chinese primary students. ZDM- Mathematics Education, 55(2), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-022-01418-7

Hunter, J., & Hunter, R. (2023). Weaving together the threads of indigenous knowledge and mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649023-10256-7

Hunter, R., Hunter, J., Anthony, G., & McChesney, K. (2018). Developing mathematical inquiry communities: Enacting culturally responsive, culturally sustaining, ambitious mathematics teaching. Set, 2, 25–32.

Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining flourishing across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

Kazemi E Franke M & Lampert M (2009). Developing pedagogies in teacher education to support novice teachers’ ability to enact ambitious instruction. In R. Hunter, B. Bicknell & T. Burgess (Eds.), Crossing divides Proceedings of the 32nd annual conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia (pp. 11-29). MERGA.

Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg, E. A., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The EPOCH measure of adolescent wellbeing. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 586. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000201

Li, Q., Cho, H., Cosso, J., & Maeda, Y. (2021). Relations between students’ mathematics anxiety and motivation to learn mathematics: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 1017–1049.

Morales, H., & DiNapoli, J. (2018). Latinx bilingual students’ perseverance on a mathematical task: A rehumanizing perspective. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 7(3), 226–250.

Mullis, I., Martin, M., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2016). TIMSS 2015 international results in mathematics. Boston College: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center.

OECD. (2013). PISA 2012 Results: Ready to learn – Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs (Vol. III). OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2015). What contributes to student wellbeing at school? OECD Publishing.

Perry, A. B. (2004). Decreasing math anxiety in college students. College Student Journal, 38(2), 321–324.

Prendergast, M., O’Meara, N., O’Hara, C., Harbison, L., & Cantley, I. (2019). Bridging the primary to secondary school mathematics divide: Teachers’ perspectives. Issues in Educational Research, 29(1), 243–260.

Riconscente, M. M. (2014). Effects of perceived teacher practices on latino high school students’ interests, self-efficacy, and achievement in mathematics. The Journal of Experimental Education, 82(1), 51–73.

Ritchie, J. (2023). Wellbeing learnings from pandemic pedagogies in aotearoa new zealand. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 58(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-023-00278-3

Samuelsson, M., & Samuelsson, J. (2016). Gender differences in boys’ and girls’ perception of teaching and learning mathematics. Open Review of Educational Research, 3(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2015.1127770

Schukajlow S (2015, July) Effects of enjoyment and boredom on students’ interest in mathematics and vice versa. In Beswick, K., Muir, T., & Wells, J. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 39th Psychology of Mathematics Education conference (Vol. 4, pp. 137-144). PME

Schukajlow, S., Rakoczy, K., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Emotions and motivation in mathematics education: Where we are today and where we need to go. ZDM—Mathematics, Education, 55(2), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-022-01463-2

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish. William Heinemann.

Skaalvik, S., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2004). Gender differences in math and verbal self-concept, performance expectations, and motivation. Sex Roles, 50, 241–252.

Strand S (2013) What accounts for ethnic achievement gaps in secondary schools in England? BERA Insights, 4 (Autumn 2013).

Supter, L., & Sollerman, S. (2023). Changes in affect: Patterns in grade 4 and grade 8 students expressed emotional directions. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 54(8), 1598–1613.

Tiberius, V. (2018). Wellbeing as value fulfillment: How we can help each other to live well. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198809494.001.0001

Tsuei, M. (2012). Using synchronous peer tutoring system to promote elementary students’ learning in mathematics. Computers and Education, 58(4), 1171–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.11.025

UNESCO. (2022). UNESCO strategy on education for health and wellbeing. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381728.

United Nations (n.d.) Sustainable development goals. www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

Watt, H. M. G., Bucich, M., & Dacosta, L. (2019). Adolescents’ motivational profiles in mathematics and science: Antecedents and consequences for engagement and wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(April), 990. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00990

Watt, H. M., Shapka, J. D., Morris, Z. A., Durik, A. M., Keating, D. P., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Gendered motivational processes affecting high school mathematics participation, educational aspirations, and career plans: A comparison of samples from australia, canada, and the united states. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1594–1611. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027838

Way, J., Attard, C., Anderson, J., Bobis, J., McMaster, H., & Cartwright, K. (2020). Researching the affective domain in mathematics education. In J. Way, C. Attard, J. Anderson, J. Bobis, H. McMaster, & K. Cartwright (Eds.), Research in mathematics education in Australasia 2016–2019 (pp. 91–115). Springer.

Widlund, A., Tuominen, H., & Korhonen, J. (2021). Development of school engagement and burnout across lower and upper secondary education: Trajectory profiles and educational outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 66, 101997.

Wilkie, K. J. (2019). Middle school boys’ and girls’ own expressions of aspirations for their mathematics learning. In M. S. Hannula, G. C. Leder, F. Morselli, M. Vollstedt, & Q. Zhang (Eds.), Affect and mathematics education (pp. 165–194). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13761-8_8

Wong, N. Y. (1995). The relationship between Hong Kong students’ perception of their mathematics classroom environment and their approaches to learning: A longitudinal study. The University of Hong Kong. Doctoral dissertation, Proquest Dissertations.

World Health Organization (n.d.) Gender and health. www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab= tab_1.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to this article’s content.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, J.L., Hunter, J. Diverse Students’ Mathematical Wellbeing. NZ J Educ Stud 59, 211–234 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00318-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00318-6