Abstract

Several years have passed since the removal of National Standards, however the current provision and enactment of music education in New Zealand remains unknown. Using a case study, this article seeks to illustrate the current practice of music education at one high decile primary school. This study finds that despite the removal National Standards, reading, writing and mathematics have continued to be prioritised, dominating classroom timetables, initial teacher education and the allocation of resources and professional development. With limited opportunities for music-making in the classroom, I argue that practice has stagnated and without targeted policies, music will continue to be marginalised within the curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Achievement in reading, writing and mathematics is increasingly considered a prerequisite for educational success. In many countries, this has resulted in the introduction of curriculum and assessment policies that prioritise numeracy and literacy to the detriment of the broader curriculum (Aróstegui, 2016; Burke, 2015). New Zealand is not immune to this trend, with the decline of music education in New Zealand being in part attributed to the introduction of National Standards, an education policy introduced in 2008 by the National-led government (Webb, 2016). This highly contested policy led to an increased focus on numeracy and literacy, setting out expected levels of achievement in reading, writing and mathematics for primary and intermediate students (Thrupp, 2018). While the Ministry of Education asserted that National Standards would “improve learning across the curriculum as a whole” (Ministry of Education, 2009), opportunities for classroom music-making continued to wane, alongside support services, resources and professional development (Carson & Rodgers, 2016; Ministry of Education, 2016).

National Standards continued to dominate education in New Zealand for almost a decade, before being removed in 2017 by the newly elected Labour-led government (Wood et al., 2021). Since the de-emphasis of National Standards, the landscape of primary education has remained relatively unknown, including how the removal of this policy has impacted the provision and enactment of music education. This article seeks to contribute to this gap, illustrating the provision of music education at one primary school in the current educational climate. I begin this article by providing a brief review of the history of music education in New Zealand, alongside the introduction and enactment of National Standards. Current educational policy will then be discussed, including signalled changes and the implications that this has for music education. I then introduce the Tuatara School case study and use this to illustrate some of the complexities around music education in primary schools post National Standards. I argue that without targeted policies, practice at Tuatara School has stagnated and continues to be susceptible to neoliberal trends that marginalise music in the curriculum.

Education Policy and Music Education in New Zealand Until 2017

Education in New Zealand was established with the 1877 Education Act, legislation that mandated free and accessible education to every child, regardless of geographical location or socioeconomic status (Lauder, 1990). Underpinned by egalitarian ideologies, this legislation established a national curriculum that fostered social mobility through the provision of equal educational opportunities (Rata, 2008). Egalitarianism remained a dominant feature of education until the 1980s, where much like the rest of the world, New Zealand began to adopt neoliberal ideologies in response to increasing financial pressures (Codd et al., 1990). These ideologies promoted the role of the free market, positing that increased autonomy and competition would improve efficiency and lead to greater economic gain (McMaster, 2013). By 1988, these ideologies had infiltrated education through the introduction of the Tomorrow’s Schools policy, positioning education as a commodity to be run along business lines (Codd, 2008). As neoliberalism became more embedded in New Zealand, the purpose of schooling quickly shifted to equip students with skills required for the job market (Siteine & Mutch, 2019). This resulted in the prioritisation of subjects that were perceived to lead to greater economic outcomes (Snook, 1990). Despite eight different learning areas being mandated in the national curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007), reading, writing and mathematics took priority, being perceived as ‘core subjects’ and ‘foundational’ to all other learning (Rickson & Legg, 2018; Wylie, 2012). These beliefs were solidified through the introduction of National Standards, as it was thought that achievement in numeracy and literacy would enable “students to achieve success across the New Zealand Curriculum” (Education Review Office, 2010, p. 13).

Under National Standards, primary schools were required to publicly report student achievement in reading, writing and mathematics. As achievement data became publicly accessible, it was used to indicate the quality of each primary school, influencing student enrolment and leading to increased competition (McMaster, 2013). With increasing pressure to improve levels of achievement, ‘uninterrupted’ class time was allocated for reading, writing and mathematics, often in the morning when the students were most engaged (Thrupp, 2013). Consequently, subjects such as music were either omitted entirely or pushed to the afternoon when children were tired and unfocused (O’Connor, 2020b; Thrupp & White, 2013). In response, some teachers promoted an integrated curriculum to ensure the coverage of all learning areas (McDowall & Hipkins, 2019), while other teachers used subjects such as music to simply supplement learning in numeracy and literacy (Irwin, 2018). While curriculum integration provided one possible solution, many teachers remained unfamiliar with this concept, due to limited support and initial teacher education programmes (Arrowsmith & Wood, 2015; Buck & Snook, 2020). Despite integration being promoted within the national curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007), it has been criticised, for failing to uphold the integrity of each subject (McDowall & Hipkins, 2019). This may explain why some teachers have condemned integration of any kind, fearful that it may threaten their classes ability to meet the National Standards (Hall, 2014).

With a fixation on numeracy and literacy, the government mandated that all primary school charters were to include specific achievement targets in relation to National Standards (Lee & Lee, 2009). Consequently, charters failed to include provision for areas of the New Zealand curriculum outside of numeracy and literacy, despite legislation stating otherwise (Fisher & Ussher, 2014). By 2014, the Investing in Educational Success policy was introduced alongside National Standards, in response to declining student achievement, evidenced by New Zealand’s decreasing PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) ranking (Barback, 2015). This policy established clusters of schools based on their geographical location, known as Communities of Learning, or Kāhui Ako. It was hoped that this policy would strengthen educational pathways, increasing communication and ensuring the provision of shared goals between schools. This occurred through the establishment of achievement challenges, that set specific targets for student achievement, initially in relation to reading, writing and mathematics (Thrupp, 2019). These achievement challenges also dictated professional development in each cluster, alongside each school’s mandated charter, limiting opportunities to upskill in the arts for well over a decade (Powell, 2019). Alongside limited opportunities for professional development, support services outside of numeracy and literacy were abolished, including district music advisors and programmes like artists in schools (Freeman, 2020). Initial teacher education also favoured numeracy and literacy, with subjects such as music being squeezed into seven and a half hours within a three year Bachelor of Education degree (Mansfield, 2010), subsequently many graduates lacked the skills and knowledge required to teach music (Trinick & Joseph, 2017). This may explain why the National Education Monitoring Report found a significant number of children unable to meet achievement objectives in music or even progress through the music curriculum itself (Ministry of Education, 2016). While inequitable access to music education existed prior to the introduction of National Standards (Braatvedt, 2002), Webb (2016) suggests that music education was further marginalised through the introduction of this policy, as numeracy and literacy dominated initial teacher education programmes, resourcing and professional development.

Policy Under the Labour-Led Government

Since the de-emphasis of National Standards, there has been no clear mandate from the government as to whether primary schools should continue adhering to the policy. With growing uncertainty, an independent taskforce was established, alongside multiple advisory groups, tasked with evaluating New Zealand’s education system (Wood et al., 2021). From these groups, several recommendations were made including the reinstatement of education hubs, local curriculum advisors and a review of the national curriculum (Curriculum Progress & Achievement Ministerial Advisory Group, 2019; Tomorrow’s Schools Independent Taskforce, 2018). While the idea of education hubs were quickly rejected (Small, 2019), a refresh of the national curriculum was welcomed and is expected by 2025 (Ministry of Education, 2021c). While this revision is currently underway, it is interesting to note that music and other art subjects are one of the last areas to be revised (Ministry of Education, 2021d). Alongside amendments to the national curriculum, achievement standards at secondary school are also being reviewed (Ministry of Education, 2020), in addition to the development of records of rich learning, outlining children’s progress across the curriculum. Similar to National Standards, records of learning will report student progress in numeracy and literacy, in addition to social emotional learning. With data accessible to teachers, parents and the wider community, it is hoped that these records will enable the identification of specific learning needs and improve communication as children move between classes and different schools (Tinetti, 2021). At this stage limited information is available and with no mention of music or the arts, it is unknown whether this framework will renew or continue to marginalise the place of music in the curriculum.

In terms of professional development, new priorities have been released since the de-emphasis of National Standards, ensuring “great education opportunities and outcomes are within reach for every learner” (Ministry of Education, 2021e). Unfortunately, this statement exclusively refers to ‘foundation skills’ in language, literacy and numeracy, with the current provision of professional development focused on curriculum design, assessment and digital fluency (Ministry of Education, 2021b). Despite limited avenues for professional development in music, a Creatives in Schools programme was introduced in 2019, enabling partnerships between schools and artists to deliver specific art-based projects (Ministry of Education, 2021a). This programme was however criticised for outsourcing the arts curriculum, rather than equipping classroom teachers with professional development and resources to enact the curriculum themselves (O’Connor, 2019). With limited literature available, it remains unknown whether this programme has impacted the provision and enactment of music education at primary and intermediate schools.

This brief overview has discussed how National Standards has contributed to the decline of music education in New Zealand, as numeracy and literacy were prioritised above all other learning areas. Alongside the removal of National Standards, I have highlighted several significant developments in the New Zealand education system, including the refresh of the national curriculum, revision of achievement standards at secondary school, the introduction of records of rich learning and the introduction of a Creatives in Schools programme. Despite these developments, their impact on music education in New Zealand remains unknown, including and whether children are once again able to access a rich and broad curriculum as the Labour-led government once promised. The following sections begin to explore this gap, outlining the methodology and findings of a singular case study.

The Tuatara School Study

A case study design was selected to explore the provision and enactment of music education at Tuatara School post National Standards. As this study is limited to one school, it is important to note that it is unable to provide generalisations or indicate the practice of other primary schools throughout New Zealand (Short et al., 2017).

Tuatara School is a well-established primary school, located in a semi-rural and affluent community. Based on the community’s high socioeconomic status, Tuatara School is classed as decile 10, receiving a smaller portion of government funding given the community’s ability to contribute to the school through donations and fundraisers (Cobb, 2019). With a roll of almost five hundred children between Year 0 and Year 6, the majority of students at Tuatara School identify as New Zealand European or Pākehā, while 11% identify as Māori, 10% as Asian and 2.5% as other. Tuatara School has eighteen different classrooms, led by teachers from a variety of backgrounds, ranging from beginning teachers, to those with over 25 years of experience. In total, the school’s staff comprises of approximately fifty-five people, including the leadership team, teaching staff, office administrators, a caretaker, a qualified librarian, and those involved in before and after school care. In addition to employed staff, Tuatara School contracts seven itinerant instrumental teachers, who according to the principal offer private tuition on every instrument except bagpipes. This includes tuition for piano, keyboard, ukulele, guitar, bass, drums, singing, violin, recorder, flute, clarinet, saxophone and music theory. These lessons are based on a user-pays system, occurring once a week for thirty min during the school day, with children coming out of class to participate, either individually or within a small group.

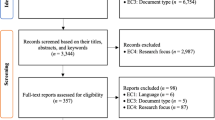

Over a six-month period, data was collected from Tuatara School using a range of qualitative methods, including an online survey, semi-structured interviews, classroom observations and document analysis. These methods involved twenty-seven participants, including the principal, members of the leadership team, classroom teachers, itinerant instrumental teachers, and parents. Data was first obtained from a short online survey, completed by eighteen classroom teachers and two members of the leadership team. This survey provided a basis for eight semi-structured interviews involving the principal, three classroom teachers, two itinerant instrumental teachers and two parents. Seven of these interviews were conducted in person and the other via Zoom. To further understand the provision and enactment of music education at Tuatara School, four classroom observations were undertaken. Observations occurred during the school day and consisted of two group singing activities, a classroom music lesson, and a rehearsal of the school’s production. Alongside other data collection methods, documents were also used to gain a historical understanding of the school (Bowen, 2009). This included the school’s strategic plan, annual reports and weekly newsletters, in addition to reports made by the Education Review Office (ERO). These documents were available through the public domain and were accessed electronically.

Obtained data was stored, organised and analysed using the computer software, NVivo. This software enabled data to be coded into different categories to identify recurring themes (Clarke & Braun, 2017). Once identified, these themes provided a rich analysis of the current provision of music education and factors which enable or constrain its enactment (Castleberry & Nolen, 2018). This research was approved by the University of Waikato Division of Education Ethics Committee and followed all ethical guidelines. To protect the identity of participants, a pseudonym has been used for the name of the school and all identifying features have been concealed where possible.

Music Provision at Tuatara School

Findings of the Tuatara School study are outlined below, illustrating the provision of music education through timetabling, resourcing and expenditure, professional development, classroom enactment and communication with parents at the school.

Timetabling

Classroom timetables throughout Tuatara School allocated a significant amount of time to reading, writing and mathematics, siloing these subjects from other learning areas. With over half of the school day dedicated solely to numeracy and literacy, other subjects were pushed to the afternoon. A classroom teacher explained that:

…the core subjects take priority and then that’s sort of the morning, you know you have your literacy and your numeracy in the morning, and then in the afternoon we do a topic or sport or something, or even art (classroom teacher 1).

This was reinforced by other classroom teachers who indicated that music is:

…unfortunately one of those subjects that always gets pushed, I mean everything is pushed to the side, other than reading, writing and maths (classroom teacher 2).

A hierarchy of subjects was also indicated by itinerant instrumental teachers, who shared pressure from parents to schedule lessons in the afternoon, ensuring that children were not missing out on ‘important schooling’. An itinerant teacher shared that:

Some parents can’t bear the thought of their child missing half an hour important schooling to learn an instrument, so they insist that it’s in the afternoon or straight afterschool or whenever (itinerant teacher 1).

Another itinerant teacher indicated that this pressure stemmed from classroom teachers who were reluctant to let children attend their instrumental lessons, sharing that:

…some of them can get quite grumpy like ‘oh they’re missing out on writing’ (itinerant teacher 2).

Interestingly, this pressure was even felt by students themselves, who worried about falling behind whenever instrumental lessons were scheduled during instruction for reading, writing or mathematics. One parent indicated that this eventually led to their child withdrawing from instrumental lessons:

…because it tended to sort of take him away from his maths and…he just didn’t like it...he got a bit stressed leaving class, so he decided to give that up (parent 1).

Despite the removal of National Standards, it is evident that classroom timetables at Tuatara School have continued to prioritise numeracy and literacy, with subjects such as music being pushed to the afternoon.

Resourcing and Expenditure

The findings of Tuatara School also indicated a hierarchy of subjects through resourcing and expenditure, as music was sidelined in favour of numeracy and literacy. Annually, the school spends between sixty and eighty thousand dollars on the curriculum and related resources, however only four hundred dollars of this budget is allocated to music, equating to less than a dollar per student. Despite this, the school has a dedicated music room, filled to the brim with a large collection of instruments, due to fundraising initiatives and parental donations, underpinned by the community’s high socioeconomic status. Many of these instruments were however unfit for purpose, being in poor condition and in desperate need of repair. The state of these instruments even led an itinerant teacher to use duct tape to piece together the skin of a snare drum, due to lack of action from the school. The itinerant teacher shared:

I have tried asking [the school] to replace stuff but… [they haven’t] quite followed through, so I’ll buy the strings and put them on the guitars and I’ve just taped up the drum kit… (itinerant teacher 2).

With limited resources available, some classroom teachers opted to bring personally owned equipment from home, while others resorted to spending money from their classroom budget. Two classroom teachers explained,

I bring in my UE Boom to play music but that’s it (classroom teacher 2).

I have just some little instruments in my class that I did buy one year when I had some money left over, like lots of little triangles and shakers… (classroom teacher 1).

Despite having a dedicated music room, Tuatara School lacked the facilities to enable group music-making, given that the music room only accommodated one student at a time. Consequently, small groups and larger instruments such the drum kit were relocated to a dilapidated shed, however this also lacked the space to accommodate a larger ensemble. An itinerant teacher elaborated:

So it’s like this old pool shed like right next to the main office. It’s like super small so it’d be like…a bit of a mission to have a band in there… (itinerant teacher 2).

While the removal of National Standards intended to restore the provision of the broad curriculum, the resourcing and provision of music education at Tuatara School leaves much to be desired.

Professional Development

In addition to resourcing, the prioritisation of numeracy and literacy was also evident through the allocation of professional development, which was restricted to reading, writing and mathematics. A classroom teacher clarified:

It’s that whole priority thing, like a lot of our PD is in literacy and maths (classroom teacher 2).

This was reinforced by a beginning teacher who explained that professional development at Tuatara School focused on the ‘main subjects’. With little provision or mention of music, it is hardly surprising that classroom teachers were unable to recall the last time they received professional development in music, with some even indicating that they never had. The lack of professional development undertaken in music was lamented by the principal, who suggested that opportunities to upskill in music were inaccessible, particularly in comparison to numeracy and literacy. The principal explained that:

…literacy and numeracy, there’s lots of courses out there. You can send teachers on courses, you can up skill…Where is the PD in music?...Is music being raised to the level it should be? I don’t think so probably…cause I don’t even know who to ask to come in and help us...who do you go to? Where do you go? (principal).

The principal later suggested that limited opportunities for professional development in music stemmed from the implementation of Kāhui Ako, which continues to favour specific subjects through the provision of professional development.

The initial roll out of the Kāhui Ako, all was based around National Standards achievements, you know, it was not based around your arts and things, and if you sent that in, you didn’t get accepted. And so everyone wrote about, you know, low student achievement and writing and those sorts of things (principal).

Without the opportunity to upskill, one classroom teacher explained that this had led them to personally pursue and pay for professional development external from the school, stating that:

I had in that year gone to [a performing arts academy] to learn ukulele myself so that I could teach it (classroom teacher 2).

Itinerant teachers were also found to pursue professional development opportunities independently from Tuatara School, however this was most likely a result of being privately contracted rather than employed. An itinerant teacher shared that they had previously undertaken professional development, however this had occurred several years ago. They explained:

I mean I did my second Orff course probably two years ago, maybe three? (itinerant teacher 1).

In addition to professional development opportunities, it was interesting to note that the itinerant staff were largely unregulated by the school and were not required to hold any specific qualifications, nor a Limited Authority to Teach (LAT). One itinerant teacher explained:

There’s heaps of tutors that don’t have that LAT I reckon... To be honest, I think just a lack of knowledge, like I didn’t hear about the LAT until I went for my job interview at [another school]. (itinerant teacher 2).

Similarly, another itinerant teacher indicated that they historically held an LAT however this was now expired.

Yeah, I mean I did an LAT a few years ago when I was working at [another school] and I was running a big choir and a big orchestra there but you know, it expires. I haven’t done it and I haven’t been asked for it... (itinerant teacher 1).

These findings suggest that music education is absent from professional development at Tuatara School, as numeracy and literacy continue to be favoured.

Curricular Enactment

Timetabling, resourcing and professional development at Tuatara School indicate that some learning areas are given more emphasis within the curriculum. Classroom teachers discussed this hierarchy directly, explaining that attitudes and expectations have stagnated since the removal of National Standards. One classroom teacher explained:

Well we’ve just come out of the National Standards and golly that dominated everything. It honestly put things back and even as a classroom teacher you didn’t have time, you weren’t being assessed on it, you weren’t being looked at it, you weren’t, no one was coming in, so it got left behind (classroom teacher 3).

Similarly, another classroom teacher shared:

I think it’s because of when we had National Standards, that the focus was on reading, writing and maths and where the kids should be. You know there’s an expectation that you do reading, writing and maths every day (classroom teacher 2).

This classroom teacher later justified this narrow focus, suggesting that music is non-essential to survival and therefore should receive less emphasis in the classroom. When questioned further, the teacher reiterated:

You don’t need reading, writing and maths to survive either but you know those are more general life skills that they’ll need for so many jobs and so many paths in their lives (classroom teacher 2).

These sentiments provide one explanation of why students within the school receive little instruction in music, with musical activities in the classroom being limited to four-min, as students sing along to YouTube, with little direction given from the teacher, apart from ‘sing louder’, ‘I can’t hear you’ or ‘come on guys, you know this!’. It is interesting to note that this is a Level 1 achievement objective from the national curriculum. In addition to group singing, several teachers indicated that they had previously taught the ukulele and recorder in their classrooms and that the students were also given the opportunity to audition for the school’s production that occurs every second year. These teachers later confessed that they did not believe that Tuatara School was currently meeting the requirements of the curriculum for music. This was reinforced when teachers discussed graduate profiles and what skills students leaving the school were expected to have, as several teachers shared that it would be ‘nothing to do with music’ or that:

…it would be very basic, like can sing the national anthem (classroom teacher 2).

These statements clearly indicate the position of music at Tuatara School and how reading, writing and mathematics continue to be prioritised.

With minimal opportunities to progress through the music curriculum, there was an assumption that if students really wanted to participate and progress in music, then they had the option to do so through private instrumental tuition available at the school. One teacher explained:

I guess if they’re really interested in it, I suppose our children are very lucky that their parents are able to provide private lessons. So, a lot of the children in my class do take private tuition if they’re really interested in it. (classroom teacher 1).

These findings continue to suggest that despite the removal of National Standards, opportunities for music-making at Tuatara School are very limited unless students are participating in private instrumental tuition.

Parent Communication

Alongside curriculum leveling, the removal of National Standards intended that parents would continue to receive two reports per year, indicating their child’s progress and achievement. It was hoped that this communication would shift from an tool of accountability, to promote partnerships and instil confidence that “every student is getting the support and opportunities to learn which they need to be successful.” (Hipkins, 2017, p. 4). At Tuatara School, student progress and achievement are communicated through termly newsletters and written reports. These newsletters are distributed to each syndicate, providing a term overview, and indicating specific learning focuses. When these focuses were discussed, parents shared that they have no recollection of music ever being mentioned. One parent explained:

So generally, we get at the start of the term, like a newsletter saying this term we’re going to focus on this for maths, this for English, this is what we’re going to do, but not so much with music and then especially last year with COVID (parent 1).

Another parent shared:

Another thing is they do send out a regular, I think it’s a term-by-term newsletter for the syndicate…so it’s a bit of an overview for the term and what their focus is but often it will include things like 'our focus this term is on the Treaty of Waitangi'. You know there is all the history and things like that that get incorporated, but I don’t ever recall seeing a focus for a term around music as such. Maybe arty elements? But not as such in that music space (parent 2).

In addition to newsletters, parents also receive a written report outlining their child’s progress every 6 months. These reports indicate student achievement in each learning area, including technology, physical education, social science, science, the arts, mathematics and writing and reading. Interestingly, reading, writing and mathematics take up majority of this report, featuring comment boxes that explicitly discuss how students are achieving against National Standards, despite these standards being disestablished. One parent explained:

So it’s a four-page booklet, so cover page and then on the inside it’s got basically a chart showing for each subject where they are actually at against the national standard… (parent 2).

This was later confirmed by the principal, who indicated that:

We still enter our data and do all this stuff, but in a bit more relaxed way I think (principal).

Interestingly these comment boxes are limited to reading, writing and mathematics, with other subjects being omitted entirely. One parent clarified:

So, when they comment, there’s sections for reading, writing and maths but nothing else (parent 2).

When asked of communication for music specifically, another parent shared:

We get a report twice a year. They do assessments and stuff for the core subjects but in terms of art and things like that, it’s just a general global thing. There won’t be any mention, any greater mention of anything, you won’t get anything else (parent 1).

Despite the abolishment of National Standards several years ago, Tuatara School continues to report student achievement against National Standards and in doing so, subjects outside of numeracy and literacy have continued to be deprioritised.

Discussion

While several years have passed since the removal of National Standards, no clear directive or policy has been enacted in its place, creating a vacuum in policy (Louis, 2006). With little regulation, Tuatara School has maintained a business-as-usual approach, continuing to use the National Standards framework to measure student achievement and teacher success. Underpinned by neoliberal ideologies that value specific subjects for their perceived economic output (Snook, 1990), it is hardly surprising that under this framework, curriculum areas are siloed, with numeracy and literacy being prioritised to the detriment of the broader curriculum. At Tuatara School, this prioritisation resulted in students rarely progressing through the music curriculum, being restricted to Level 1 achievement objectives. With little opportunity for music-making in the classroom, the obtainment of skills associated with music education are restricted. This includes the obtainment of transferable skills such as analytical, creative, co-operative, entrepreneurial, critical thinking and problem-solving (Ministry of Education, 2000), all of which are ironically desirable in a neoliberal society, even being described as ‘key to a striving economy’ (O’Connor, 2020a).

Through the promotion of privatisation, managerialism, performativity and marketisation, neoliberal ideologies have guided the practice of Tuatara School, in lieu of a policy dictating otherwise. Privatisation occurred at Tuatara School as the music curriculum primarily occurred through instrumental tuition that was outsourced to the private sector through independent contractors. While it can be argued that contracting specialist teachers ensures the breath of curricular enactment (Thrupp et al., 2021), it is interesting to note that these contractors remained largely unregulated by the school. With no requirement to hold Teacher Registration, a Practising Certificate, LAT or any specific qualifications, these contractors operated almost entirely independent from the school, being absent from any type of staff-wide professional development. Without any regulation, the provision of music at Tuatara School was deemed successful solely by the individual consumer.

In addition to privatisation, elements of managerialism were also evident through the adoption of a business-like model that encouraged a culture of performance, as focus was placed on targets and outcomes (Thrupp, 2018). This occurred through the adoption of a strategic plan, a document derived from the business sector to direct performance outcomes and how these will be achieved (Kapucu, 2021). Tuatara School’s strategic plan set specific targets for achievement in reading, writing and mathematics that students would be measured against throughout the year. To ensure these targets were met, timetables, professional development and resources focused solely on numeracy and literacy. Unfortunately, for music this resulted in an absence of professional development, a minuscule budget, and a lack of appropriate resources. With Tuatara School being classed as decile 10, it is interesting to note that affluent schools are commonly found to provide better opportunities in music (Brasche & Thorn, 2018), due to the cost of musical resources (Donaldson, 2012). While many of Tuatara School’s musical resources were broken or unfit for purpose, the school was still advantaged by the financial support of the community, having a dedicated music room and a large collection of instruments, a privilege that may not have been possible in lower socioeconomic communities. Despite this privilege, the limited opportunities for music education at Tuatara School suggests that the decile system continues to be an inadequate measure of educational success (Gordon, 2015).

Alongside managerialism, elements of performativity and marketisation were also evident, with key performance indicators being used to measure success (Ball, 2003). In education this commonly occurs when government agencies such as ERO use student achievement data to evaluate school practice (Wallace, 2015). With achievement in numeracy and literacy underpinning ERO judgements, Tuatara School focused almost exclusively on these two learning areas to maintain positive reviews. As discussed, Tuatara School also set their own targets to increase student achievement in reading, writing and mathematics evidenced through the school’s strategic plan. Accountable to parents and the broader community, Tuatara School regularly reported against these targets through student-led conferences, student reports and annual reports, alongside the strategic plan itself. With the marketisation of schools, it seems that these measures have been undertaken to maintain a reputation that encourages student enrolment. Despite the dominance of performativity at Tuatara School, this seems to be limited to numeracy and literacy, which were initially promoted by National Standards given these learning areas were considered the easiest to measure (Wylie, 2012). Given the wide range of assessments used for music and the long history of examination boards in New Zealand (Southcott, 2017; Wesolowski, 2020), perhaps it is not necessarily that music is harder to assess but that teachers lack the skills to do so.

While the practice of Tuatara School is not surprising given the policy void created by the deemphasis of National Standards, it is interesting to note how classroom and itinerant teachers have responded, exercising their own sense of agency. According to Soler and Fuentes (2021), this is not uncommon, with school practice often being dictated by staff when schools are left to operate without guiding policies. Teacher agency at Tuatara School was evident through resourcing, as itinerant teachers attempted to repair broken instruments, using duct tape to salvage the skin of a snare drum, or even replacing guitar strings with ones that they had personally purchased. Classroom teachers responded similarly, opting to use their classroom budget for musical resources or even choosing to bring personally owned resources from home. One teacher even resorted to personally funding their own professional development to ensure they had the skills required to enact the music curriculum. While these findings are encouraging, they continue to reinforce that music has become reliant on individual teachers’ expertise and enthusiasm, rather than a unified approach across the staff (Wylie, 2012). With opportunities for music-making being dictated by individual teachers, music education at Tuatara School has become a privilege for a select few.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that a policy vacuum has been created since the disestablishment of National Standards and that without clear directive from the government, primary schools have been left largely to their own devices. While this research is unable to provide generalisations (Short et al., 2017), it provides an example of what may occur in a policy vacuum, cautioning other countries to think twice before educational policy is removed. At Tuatara School, a void in policy ensured the continuation of National Standards and neoliberal ideologies that prioritise numeracy and literacy. While change is on the horizon with a refresh of the national curriculum and other changes proposed, Mordechay and Orfield (2017), suggest that current issues will continue unless addressed by targeted policies. To ensure all learning areas are fully realised, educational policy needs to promote a balanced curriculum, ensuring all teachers are adequately prepared to teach music through initial teacher education and accessible professional development. Given the cost associated with the music curriculum, resourcing also needs to be addressed to ensure that facilities and musical resources are fit for purpose. Until targeted policies are introduced, and neoliberal ideologies are abandoned, it seems that at Tuatara School, music education will continue to be superfluous to the rest of the curriculum.

References

Aróstegui, J. L. (2016). Exploring the global decline of music education. Arts Education Policy Review, 117(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2015.1007406

Arrowsmith, S., & Wood, B. E. (2015). Curriculum integration in New Zealand secondary schools: Lessons learned from four “early adopter” schools. Set: Research Information for Teachers https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0009

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

Barback, J. (2015). Investing in Educational Success (IES) - moving on from stalemate. Education Central. https://educationcentral.co.nz/investing-in-educational-success-ies-moving-on-from-stalemate/

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Braatvedt, S. (2002). A history of music education in New Zealand state primary and intermediate schools 1878–1989 [Doctoral thesis, University of Canterbury].

Brasche, I., & Thorn, B. (2018). Addressing dimensions of “the great moral wrong”: How inequity in music education is polarizing the academic potential of Australian students. Arts Education Policy Review, 119(3), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2016.1201029

Buck, R., & Snook, B. (2020). Reality bites: Implementing arts integration. Research in Dance Education, 21(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2020.1727873

Burke, H. (2015). Once more around the parade ground: Re-envisioning standards-based music education in England, the USA and Australia. Australian Journal of Music Education (2), 49–65.

Carson, T., & Rodgers, L. (2016). Music teachers point to crisis in primary schools [Interview]. Radio New Zealand.

Castleberry, A., & Nolen, A. (2018). Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10(6), 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Cobb, D. J. (2019). Access to primary education (New Zealand). Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350995925.0022

Codd, J., Harker, R., & Nash, R. (1990). Education, politics and the economic crisis. In J. Codd, R. Harker, & R. Nash (Eds.), Political issues in New Zealand education (2nd ed., pp. 7–21). Dunmore Press.

Codd, J. (2008). Neoliberalism, globalisation and the deprofessionalisation of teachers. In V. Carpenter, J. Jesson, P. Roberts, & M. Stephenson (Eds.), Ngā kaupapa here: Connections and contradictions in education (pp. 14–24). Cengage Learner.

Curriculum Progress and Achievement Ministerial Advisory Group. (2019). Strengthening curriculum, progress, and achievement in a system that learns.

Donaldson, J. (2012). Between two worlds: Tensions of practice encountered by secondary school music teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand [Doctoral thesis, Massey University].

Education Review Office. (2010). Working with the National Standards within the New Zealand curriculum. Education Review Office.

Fisher, A., & Ussher, B. (2014). A cautionary tale: What are the signs telling us? Curriculum versus standards reflected in schools planning. New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 11(2), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.24135/teacherswork.v11i2.71

Freeman, L. (2020). Leading educators say New Zealand arts education is in crisis. Radio New Zealand. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/standing-room-only/audio/2018731319/leading-educators-say-new-zealand-arts-education-is-in-crisis

Gordon, L. (2015). ‘Rich’ and ‘poor’ schools revisited. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0011-2

Hall, S. (2014). Holistic education: A vision for 21st century New Zealand primary school classrooms [Masters thesis, University of Waikato].

Hipkins, C. (2017). Removing ngā whanaketanga rumaki māori and National Standards and stopping the transfer of teacher professional learning and development to the educational council.

Irwin, M. R. (2018). Arts shoved aside: Changing art practices in primary schools since the introduction of National Standards. The International Journal of Art & Design Education, 37(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12096

Kapucu, N. (2021). Strategic planning. Britannica Academic. https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.waikato.ac.nz/levels/collegiate/article/strategic-planning/601044#article-contributors

Lauder, H. (1990). Education, democracy and the crisis of the welfare state. In H. Lauder & C. Wylie (Eds.), Towards successful schooling (pp. 33–52). The Falmer Press.

Lee, H., & Lee, G. (2009). Will no child be left behind? The politics and history of National Standards and testing in New Zealand primary schools. Teachers and Curriculum, 11, 35–50.

Louis, K. S. (2006). Policy research in a policy vacuum. In Organizing for school change (pp. 301–325). Taylor & Francis Group.

Mansfield, J. (2010). ‘Literacies’ in the arts: A new order of presence. Policy Futures in Education, 8(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2010.8.1.99

McDowall, S., & Hipkins, R. (2019). Curriculum integration: What is happening in New Zealand schools? New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

McMaster, C. (2013). Working the ‘shady spaces’: Resisting neoliberal hegemony in New Zealand education. Policy Futures in Education, 11(5), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2013.11.5.523

Ministry of Education. (2000). The arts in the New Zealand curriculum. Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2009). The National Standards. Ministry of Education,. https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/Curriculum-resources/NZC-Updates/NZC-update-2#2

Ministry of Education. (2016). National monitoring study of student achievement report 10.4: Music - sound arts 2015 - key findings (National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement). Educational Assessment Research Unit & New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Ministry of Education. (2020). NCEA education. Ministry of Education. https://ncea.education.govt.nz/page/overview

Ministry of Education. (2021d). Roadmap: Refreshing the New Zealand curriculum for schooling.

Ministry of Education. (2021e). The statement of national education and learning priorities (NELP) and the tertiary education strategy (TES) Ministry of Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/the-statement-of-national-education-and-learning-priorities-nelp-and-the-tertiary-education-strategy-tes/

Ministry of Education. (2021c). Refresh of the national curriculum for schooling. Ministry of Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/information-releases/issue-specific-releases/national-curriculum-refresh/

Ministry of Education. (2021a). Creatives in schools. Ministry of Education. https://artsonline.tki.org.nz/Teaching-and-Learning/Creatives-in-Schools

Ministry of Education. (2021b). National priorities for professional learning and development. New Zealand Government. https://conversation.education.govt.nz/conversations/curriculum-progress-and-achievement/national-priorities-for-professional-learning-and-development/

Mordechay, K., & Orfield, G. (2017). Demographic transformation in a policy vacuum: The changing face of U.S metropolitan society and challenges for public schools. The Educational Forum. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2017.1280758

O’Connor, P. (2019). Why are we not resourcing all teachers to be creatives? Education Central. https://educationcentral.co.nz/opinion-peter-oconnor-why-are-we-not-resourcing-all-teachers-to-be-creatives/

O’Connor, P. (2020b). Teachers hope to end “near death” of arts in school. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/ideasroom/arts-leaders-hope-to-end-near-death-of-arts-in-school

O’Connor, P. (2020a). Replanting creativity during post-normal times. University of Auckland.

Powell, D. (2019). Revealing the privatisation of education. In M. F. Hill & M. Thrupp (Eds.), The professional practice of teaching in New Zealand (6th ed., pp. 256–272). Cengage Learning Australia.

Rata, E. (2008). The politics of educational equality. In V. Carpenter, J. Jesson, P. Roberts, & M. Stephenson (Eds.), Ngā kaupapa here: Connections and contradictions in education (pp. 36–46). Cengage Learning.

Rickson, D., & Legg, R. (2018). Daily singing in a school severely affected by earthquakes: Potentially contributing to both wellbeing and music education agendas? New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 15(1), 63–84.

Short, M., Barton, H., Cooper, B., Woolven, M., Loos, M., & Devos, J. (2017). The power of the case study within practice, education and research. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(1), 92–106.

Siteine, A., & Mutch, C. (2019). Historical context of primary education (New Zealand). Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350995949.0008

Small, Z. (2019). Tomorrow’s schools review: Government rejects ‘disruptive’ education hubs idea. Newshub. https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2019/11/tomorrow-s-schools-review-government-rejects-disruptive-education-hubs-idea.html

Snook, I. (1990). Contesting the curriculum: The politics of ‘basics and frills.’ In J. Codd, R. Harker, & R. Nash (Eds.), Political issues in New Zealand education (pp. 303–319). Dunmore Press Limited.

Soler, I. G., & Fuentes, R. (2021). Navigating a policy vacuum in the new Latino diaspora: Teaching Spanish as a heritage language in Tennessee high schools. Foreign Language Annals. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12505

Southcott, J. (2017). Examining Australia: The activities of four examiners of the Associated Board for the Royal Schools of Music in 1923. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, 39(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536600617709543

Thrupp, M., & White, M. (2013). Research, analysis and insight into National Standards (RAINS) project.

Thrupp, M. (2013). National Standards for student achievement: Is New Zealand’s idiosyncratic approach any better? Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 36(2), 99–110.

Thrupp, M. (2018). The search for better educational standards: A cautionary tale. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61959-0

Thrupp, M. (2019). To be ‘in the tent’ or abandon it?: A school clusters policy and the responses of New Zealand educational leaders. In J. Wilkinson, R. Niesche, & S. Eacott (Eds.), Challenges for public education (pp. 132–144). Routledge.

Thrupp, M., Powell, D., O’Neill, J., Chernoff, S., & Seppänen, P. (2021). Private actors in New Zealand schooling: Towards an account of enablers and constraints since the 1980s. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-021-00194-4

Tinetti, J. (2021). Refreshing the national curriculum for schooling.

Tomorrow’s Schools Independent Taskforce. (2018). Our schooling futures: Stronger together. Whiria ngā kura tūātinitini. Ministry of Education.

Trinick, R., & Joseph, D. (2017). Challenging constraints or constraining challenges: Initial teacher primary music education across the Tasman. New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 14(1), 50–68.

Wallace, S. (2015). Performativity. In Dictionary of Education. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199679393.001.0001/acref-9780199679393-e-754

Webb, L. (2016). Music in beginning teacher classrooms: A mismatch between policy, philosophy, and practice. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 17(12), 1–14.

Wesolowski, B. C. (2020). “Classroometrics”: The validity, reliability, and fairness of classroom music assessments. Music Educators Journal, 106(3), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432119894634

Wood, B., Thrupp, M., & Barker, M. (2021). Education policy: Changes and continuities since 1999. In G. Hassall & G. Karacaoglu (Eds.), Social policy in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 273–285). Massey University Press.

Wylie, C. (2012). Vital connections: Why we need more than self-managing schools. NZCER Press.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Browne, J. Out of the Woods Yet? The Continuing Impact of National Standards on New Zealand Music Education. NZ J Educ Stud 57, 213–229 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-022-00243-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-022-00243-6