Abstract

On the one hand, research on religious education is done according to a transnational scientific paradigm, on the other hand, it is performed within particular institutional contexts which vary from nation to nation.This raises the question of how institutional context affect research on religious education. The paper addresses this question on the basis of an international study. N = 49 colleagues across Europe as well as Israel, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey filled in an online-questionnaire regarding their own research. Despite the international character of the sample, research on religious education seems to be practiced quite coherently in regard of the objects of inquiry, the applied methods, and the disciplines the colleagues refer to. The few significant differences indicate that theology and educational studies are slightly more important in contexts of denominational religious education as well as analysing both pupils and processes of teaching and learning. In the context of non-denominational RE, instead, religious studies is slightly more important. These results will be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The goal and character of religious education are currently the subject of controversial debate. In Europe, for example, some are calling for religious education to be replaced by worldview education (Halafoff et al., 2016; van der Kooij et al., 2017), while others argue for a more spiritual layout of this subject (Roebben, 2021). In Latin America and Africa, in turn, the trending topic seems to be the decolonialization of religious education with the goal of overcoming a dominant Christian bias (Blank de Oliveira & Riske-Koch, 2021; Drange, 2015; Matemba, 2021; Mokotso, 2020). And there are still the pending questions of what teachers of religious education have to know to competently teach that subject (Whitworth, 2020), which type of knowledge this could be (Moore, 2007), and which competencies are required to offer an effective religious education (Helbling & Riegel, 2021).

These academic debates take place within diverse institutional contexts regarding the practice of religious education at schools. It reveals a multifaceted picture ranging from various denominational forms to non-denominational ones (Jackson, 2007; Kuyk et al., 2007; Rosenblith, 2017; Rothgangel, et al., 2014a, 2014b, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c). Of course, this basic distinction between denominational and non-denominational religious education does not capture the manifold forms in which religion is taught at schools in the various national contexts. Going into detail, denominational religious education varies between confessional layouts like in Italy (Giorda, 2015), Chile (Guzman et al., 2021), or South Korea (Kim, 2018) to ones realizing a “learning from religion” approach like in Germany (Kropač, 2021). Non-denominational religious education, instead, follows a pure religious studies approach to some extent (Alberts, 2007; Kenngott, 2017), partly happening within a formative frame of reference which allows for identification with religions and worldviews (Bietenhard et al., 2015; Bleisch, 2017). Furthermore, there are cross-sectional types of religious education like in Finland, which is in legal perspective denominational and in pedagogical perspective multi-religious (Lipiäinen et al., 2020). Finally, in some cases, the character of religious education varies even within one national context. In Germany, for example, denominational education is the default type of religious education, but in the federal states of Bremen and Brandenburg, religion is taught in a non-denominational manner (Kropač, 2021).

Despite these pluriform institutional contexts of teaching religion at schools, within the national academic discourses on religious education there seem to exist quite coherent frames of reference. In Italy, for example, the discussion on how to do justice to religious diversity in the classroom takes place within the framework of denominational education. Non-denominational forms are mentioned, but always as alternatives to the default denominational model (Giorda, 2015). The same is true for Chile (Guzman et al., 2021), South Korea (Kim, 2018), and Germany (Kropač, 2021). In contrast, in England and Wales, the discussion of whether replacing religious education by worldview education is happening within a non-denominational frame of reference (CoRE. Commission on Religious Education, 2018). It seems to be common sense in that particular discourse that religion must be taught at schools beyond specific denominational accounts. The same also applies to the situation in Finland (Ubani et al., 2019), Belgium, and the Netherlands (Miedema, 2014), as well as the recent discourse in Switzerland (Bleisch, 2017).

These academic discourses on religious education are embedded in a transnational understanding of science. Scientific discourse works according to both rational standards and research agendas that do not vary much across national contexts (e.g., Godfrey-Smith, 2003; Gutting, 2005). Scientific disciplines are characterized by a particular epistemological paradigm, a distinct set of objects to be analyzed, well-defined methods, and a specific set of theories that these analyses refer to. National and regional particularities may be relevant on the level of single projects and discussions, but hardly play a role on the general level. In the postcolonial discourse in religious education, for example, the country’s particular national history is part of the discussion on the national level. Nonetheless, all these national discussions share the same goal of overcoming colonial structures and apply the same epistemology, refer to the same categories, and use similar methods to realize this goal. And if the field of didacticFootnote 1 research is regarded, a recent Delphi study in Germany found that the various didactic disciplines share a common understanding of the objects they analyze, the methods they use in this analysis, and the academic disciplines they refer to (Riegel & Rothgangel, 2023).

If one relates these different observations to each other, a complex picture emerges. On the one hand, on an international level, there is a controversial debate on both the goal and character of religious education in schools, and there are different institutional contexts in which this subject is taught at school. On the other hand, the academic discussion about religious education takes place within the framework of coherent frames of reference and the self-identification of this academic discourse as a science follows transnational standards. Given this complex picture, the question of how the institutional context on a national level characterizes research in religious education across various countries is raised. From the perspective of systems theory (Runkel & Burkart, 2005), one could argue that religious education on the one hand and the academic discourse on religious education on the other hand are two separate systems, each following a particular ratio. According to Luhmann, the basic goal of the educational system is to transmit knowledge and competencies to qualify its users for their future tasks (Luhmann, 2002). The scientific system is instead oriented towards corroborating the truth of its hypotheses (Luhmann, 1992). Since both goals are basically incompatible, one could assume that the dominant institutional context of religious education on a national level does not coin the academic discourse on religious education.

From an ecosystemic perspective, however, institutional contexts frame the actions of the persons within that context. Bronfenbrenner, for example, distinguishes between mesosystems and microsystems (Lüscher & Bronfenbrenner, 1981). While the microsystem represents the individuals’ zones of interactions, the mesosystems reflect the institutional or organizational context of the individuals’ actions. The idea of Bronfenbrenner’s approach is that every microsystem depends on the options and restrictions of the mesosystems in which it is embedded. In our case, religious education researchers are members of faculties and departments at universities and teacher colleges. These faculties and departments more or less mirror the basic structure of the dominant model of religious education in the relevant national context: In countries with a dominant denominational model of religious education, the faculties and departments are, in most cases, of theological character, while in nations with a non-denominational model of religious education, the nature of relevant faculties and departments is usually that of religious studies. From an ecosystemic perspective, such particular institutional characteristics should frame the researchers’ activity and therefore the relevant academic discourse on a national level.

On theoretical grounds, one cannot estimate how much of the character of the academic discourse on religious education on an international level can be explained by systems theory or ecosystemic theory respectively. Therefore, this paper addresses the following research questions:

-

(1)

What are the basic features of research in religious education on an international level?

-

(2)

Does the institutional context of religious education on a national level cause characteristic differences in these features?

2 Sample, method, measures and analysis

2.1 Sample

To answer these questions, this paper uses data from an international survey. The sample of the international study was collected via academic networks like ISREV and NCRE as well as via contacts within the project "Religious Education in Schools in Europe". Through these channels, the participants were informed about the scope of the study and invited to fill out a questionnaire with both open-ended and closed-ended questions. Finally, 49 religious education teachers across Europe as well as Israel, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey responded to this invitation. On a national level, the answers are distributed as follows: Norway: 5 answers; Turkey and Greece: 4 answers each; Germany, England and Wales, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Netherlands: 3 answers each; Poland: 2 answers; Czechia, Finland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, South Africa, and South Korea: 1 answer each. 12 participants did not disclose their national background. In terms of religious belonging, 15 participants are protestant, 12 are roman-catholic, 6 Muslim, 1 Jewish, and 6 express another religious tradition. Nine participants did not respond to this question. All respondents work at an institution offering training for future religion teachers and hold a PhD.

2.2 Measures

As indicator of academic discourse, the respondents’ research practice was chosen. From this perspective, the academic discourse is what scholars fundamentally do. This practice was conceptualized according to the three dimensions of (i) objects of inquiry, (ii) methods applied in research, and (iii) the disciplines the respondents refer to in their research. The objects of inquiry reveal the topics that are addressed in research, the methods in use indicate how these topics are addressed, and the reference disciplines offer information on which basic theoretical ground this research takes place. Since these dimensions represent basic patterns of research within the philosophy of science (e.g. Godfrey-Smith, 2003; Gutting, 2005), this conceptualization of research seems to be appropriate.

In the questionnaire, each dimension was operationalized by a closed-ended question offering a possible operationalization of each dimension, and the participants were asked to estimate how relevant they consider each category of this operationalization in their own research. Respondents were able to answer on a six-point Likert scale (1 = “not important at all”; 6 = “very important”). In order to be able to trace residual options, the option "I cannot assess" was additionally offered.

To assess the relevance of institutional context, the variable of nationality was recoded. The criteria were the dominant frame of reference according to which religious education is discussed in the relevant country. The countries with a denominational frame of reference form one category (Czechia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, South Korea, Turkey) and those with a non-denominational frame form another (England and Wales, Finland, Norway, South Africa, the Netherlands). With this recoded variable, it is possible to test the previously mentioned assumption of the effect of institutional context on academic discourse.

2.3 Analysis

Data analysis follows a two-step procedure. First, to reconstruct the basic features within the field of research in religious education, descriptive statistics of the single categories on the three basic dimensions of methodologies, objects of inquiry, and reference dimensions will be calculated. Because of the ordinal nature of the quantitative data, data analysis refers to median (Mdn) and interquartile range (IQR) and presents its results as a boxplot graph.

Second, the effect of the institutional context is tested by a Whitney–Mann U-Test. The effect size is calculated by Pearson’s r according to Cohen’s benchmarks (Cohen, 1988). All statistical calculations are done with the software package SPSS 27.

3 Results

The results will be described according to the two research questions. First, the basic features of research in religious education will be reconstructed, after which the impact of institutional context on this research will be tested.

3.1 The basic features of research in religious education

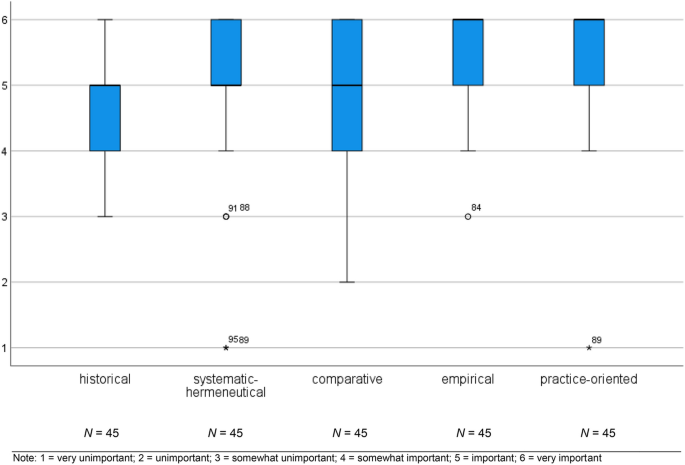

Regarding methodologies, six categories were offered to the participants: historical, systematic-hermeneutical, comparative, empirical, and practice-oriented research. There are two methodical approaches to the field of religious education that show a median of Mdn = 6, namely the empirical and the practice-oriented ones (Fig. 1). This indicates that both methodologies are very important in the respondents’ research. The other three methodical approaches have a median of Mdn = 5, indicating that these methodologies are important, but less so. The range of the answers is rather small, with only the comparative approach having an IQR = 2. Further on, there are only three extreme values. All in all, this indicates a rather coherent evaluation of the five methodical approaches within the international sample, with all five offered categories regarded as no less than important as features of methodology in research in religious education.

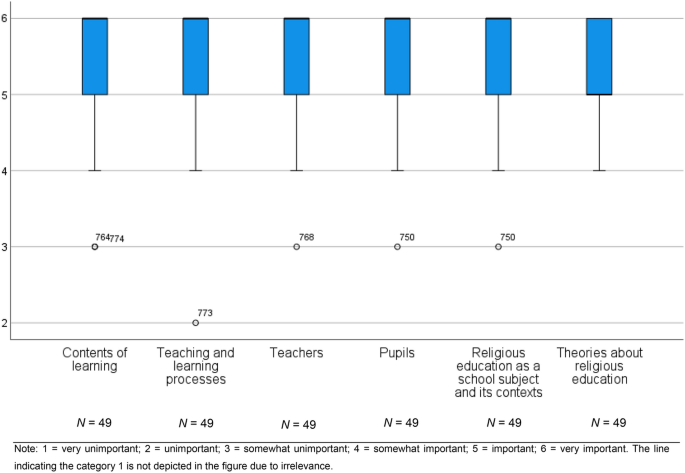

Regarding the objects of inquiry, the respondents were asked, “how important [they] consider the following characteristic topics in [their] own research activities in religious didactics”. The offered categories were contents of learning, the teaching and learning process, teachers, pupils, religious education as a school subject and its contexts, and theories about religious education. All but one topic were regarded as very important with Mdn = 6; only theories about religious education were considered to be important (Mdn = 5) (Fig. 2). Again, the respondents from various countries were quite coherent in their evaluation, with IQR = 1 on all topics and no extreme values.

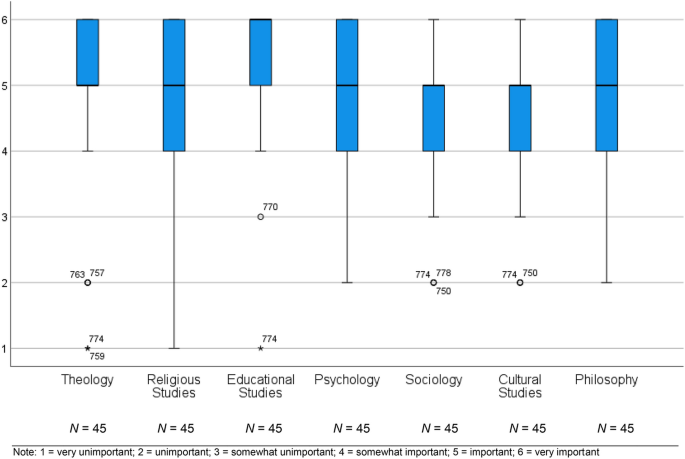

The relevance of the various reference disciplines in religious education research was assessed by the following question: “How important do you consider the following reference disciplines for your own research activities in religious didactics?” The options were theology, religious studies, educational studies, psychology, sociology, cultural studies, and philosophy. Educational studies were the only ones that were very important to most of the respondents (Mdn = 6), while all other means of reference disciplines were evaluated as important (Mdn = 5) (Fig. 3). This time, there was some variance in the answers, particularly regarding religious studies, psychology, and philosophy. All these disciplines show an IQR = 2, with the whiskers covering the entire spectrum of possible answers in the case of religious studies and the entire spectrum but one answer category in the cases of psychology and philosophy respectively. This is a remarkable finding given the quite coherent responses so far.

3.2 The impact of institutional context

Assessing the effect of the institutional context on the importance of methodologies, the Mann–Whitney-U-Test brings about one significant difference. The participants within the context of denominational religious education (Mdn = 6) regard systematic-hermeneutical methodologies as more important than the scholars researching within a context of non-denominational religious education (Mdn = 5), U(Nden = 22; Nnon-den = 13) = 83.500; z = − 2.318; p = .02). The effect of this difference is medium-sized according to Cohen (1992) (r = .39). The importance of the other methodologies is not affected significantly by the respondents’ institutional context.

If objects of inquiry are taken into account, two significant differences occur. In both cases, the participants within a denominational context regard the relevant object of inquiry as very important in one’s own research (Mdn = 6), while the researchers within a non-denominational context regard them as important (Mdn = 5). These topics are the process of teaching and learning (U(Nden = 24; Nnon-den = 13) = 73.000; z = − 3.083; p = .002) and the pupils (U(Nden = 24; Nnon-den = 13) = 82.500; z = − 2.603; p = .009) respectively. The effect of institutional context on the evaluation of processes of teaching and learning is strong (r = .51), which in the evaluation of the importance of researching pupils is medium-sized (r = .43).

Finally, institutional context explains the variance in three cases of reference theories to some extent. Theology is a more important reference discipline to respondents from a denominational context (Mdn = 6) than to those from a non-denominational context (Mdn = 4) (U(Nden = 24; Nnon-den = 12) = 75.500; z = − 2.471; p = .013), having a medium-sized effect (r = .41). Religious studies, in turn, is more important to scholars within a non-denominational context (Mdn = 6) than to those from a denominational context (Mdn = 5) (U(Nden = 24; Nnon-den = 12) = 92.500; z = − 2.121; p = .034). Again, the effect size is medium (r = .35). Finally, the respondents within a denominational context regard educational studies (Mdn = 6) as more import than those within a non-denominational context (Mdn = 5) (U(Nden = 24; Nnon-den = 13) = 96.500; z = − 2.007; p = .045). The effect of institutional context is medium (r = .33).

4 Discussion

This article aims to map the field of research in religious education on an international level and to assess the effect of the institutional context on the features of this field. The mapping happened according to the three dimensions of methodologies, objects of inquiry, and reference disciplines. All in all, there are two noteworthy results.

Firstly, across the various countries of this sample, the respondents from religious education predominantly apply empirical and practice-oriented methods, refer theoretically most often to educational studies and theology or religious studies, respectively, and turn out to be generalists in terms of the topics they analyze. Beyond this common ground of research on religious education on international level, there are some categories of lesser importance. If methods are regarded, historical and comparative ones seem to be least important. In view of the recent call for an international knowledge transfer (Schweitzer & Schreiner, 2020), the relative importance of comparative methods in particular raises the question of how to promote this transfer. Then, within the reference disciplines, it is religious studies, psychology and philosophy that show a remarkable variance in their importance for the respondents’ research. Some of the participants regard these disciplines as very important, others as unimportant (psychology and philosophy) or even very unimportant (religious studies) for their academic projects. In sum, there is much coherence in the academic discourse on religious education on an international level with some remarkable differences.

Secondly, this paper analyzes the assumption that such differences are caused by the institutional context on a national level. It hypothesizes that the dominant idea of how to teach religion in schools frames the academic discourse on this education. According to the findings, this assumption is true to some extent, but not in the way it was expected. First, four of the five categories with a bigger variance in the answers were not affected by institutional context. Neither the importance of historical and comparative methods nor the importance of psychology and philosophy as disciplines referred to in one’s projects is explained by the fact that religious education in one’s country is taught predominantly according to a denominational or a non-denominational model respectively. Only the importance of religious studies as a reference discipline is explained by this context to some extent. This result points to a rather remote effect of institutional context on the academic discourse in religious education.

Nonetheless, there are six categories with significant differences caused by institutional context. Besides religious studies, which is more important to scholars within a non-denominational context, theology and educational studies are more important reference theories to researchers from a denominational context. The same is true for the use of systematic-hermeneutical methods and the analysis of processes of teaching and learning and pupils respectively. Since the effect of these differences is at least medium-sized, one cannot speak of differences of minor importance. Furthermore, the effect turns out to be significant, although the variance in the answers of five categories (systematic-hermeneutical methods, teaching and learning processes, pupils, theology, educational studies) is rather small. This indicates that institutional context on a national level indeed coins research on religious education. In more detail, it is not the national context itself, but the dominant model of religious education at schools in the country.

From an ecosystemic perspective, these findings are quite plausible (Lüscher & Bronfenbrenner, 1981). For example, the denominational context refers to theology as a basic academic discipline which is very skilled in systematic-hermeneutical methods itself (Ford, 2013; Jung, 2004). At the same time, the higher importance of religious studies in a non-denominational context can be explained by the constitutive role of this academic subject for the relevant type of religious education. The findings further support the often criticized distinction between denominational and non-denominational religious education. Of course, this distinction is rather bold and is not able to map the subtle differences within these basic accounts of how religion is taught at schools (Jackson, 2007). Nevertheless, it is able to reconstruct fundamental differences in the study of religious education. Particularly in fields that are not analyzed intensely yet, like the basic features of the academic discourse on international level, it is useful for tracing fundamental patterns and therefore offers a solid basis for more detailed analysis.

Beyond these basic differences, from a systems theoretical perspective, the coherence within most of the respondents’ answers is plausible, too (Runkel & Burkart, 2005). As researchers, the participants are part of a system with its own authentic norms and practices. Since scientific rationality, at least in its modern condition, is predominantly designed to not be context-sensitive (Weinberg, 2016), institutional context should not affect the participants’ research practice very much. Therefore, the international field of research on religious education appears to be quite coherent. The few significant differences in regard to institutional context, however, reveal that the modern perception of science is an ideal type in the Weberian sense. Beyond the great coherence within the academic discourse on religious education on an international level, there are important differences, many of which are affected by the dominant model of religious education in one’s country. Therefore, it would be beneficial to further analyze the context sensitivity of religious education research in a more detailed manner. Perhaps such studies will shed light onto more significant path dependencies of such research—for instance also in regard to intersectional categories like gender (Sprague, 2016) or continent (Boisselle, 2016). Such research would contribute to the international knowledge transfer within religious education (Schweitzer & Schreiner, 2020).

There are, of course, also some limitations to this study. Firstly, it is a convenience sample and therefore not suited to offer representative findings. For example, the sample was recruited via established academic networks, which systematically sorts out all potential participants that are not present in these networks. This might lead to some imbalance in the answers. However, since this article aims to reconstruct basic structures and not representative findings, this limitation does not fundamentally limit the significance of the findings. Secondly, despite all efforts to collect an international sample, the sample has a strong European bias. Perhaps the great coherence in the evaluation of objects of inquiry would crack if there had been more participants from Latin America, Asia, or Africa. Differences according to one’s perspective on post-colonial claims, for example, might not be seen in a predominantly European sample. Again, although this limitation restricts the scope of the findings somewhat, it does not conflict with their validity. These limitations indicate that more religious education research on an international level is needed.

Notes

In the English-speaking context, ‘didactics’ is a term in need of clarification, because in this context, it often has a methodically specific undertone. Nevertheless, it should be noted that in many parts of Europe (such as the French- and German-speaking contexts, the context of Slavic and to a large extent Scandinavian languages) the term ‘didactics’ expresses the scientific reflection of teaching and learning, with the school context often being the main focus. We use the term didactics in this more general sense here.

References

Alberts, W. (2007). Integrative religious education in Europe: A study-of-religions approach. Walter De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110971347

Bietenhard, S., Helbling, D., & Schmid, K. (Eds.). (2015). Ethik, Religionen, Gemeinschaft: Ein Studienbuch. hep.

Blank de Oliveira, L., & Riske-Koch, S. (2021). Formação Docente e Ensino Religioso: Exercícios Decoloniais em Territórios Latino-Americanos. Revista Pistis & Praxis, 13(1), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.7213/2175-1838.13.01.DS09

Bleisch, P. (2017). Didaktische Überlegungen zum Unterricht in Religionskunde in einer religionspluralen Gesellschaft. In P. Büttgen, A. Roggenkamp, & T. Schlag (Eds.), Religion und Philosophie: Perspektivische Zugänge zur Lehrer- und Lehrerinnenausbildung in Deutschland, Frankreich und der Schweiz (pp. 179–197). Evangelische Verlagsanstalt.

Boisselle, L. N. (2016). Decolonizing science and science education in a postcolonial space (trinidad, a developing Caribbean Nation, illustrates). SAGE Open, 6(1), 215824401663525. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016635257

CoRE. Commission on Religious Education. (2018). Religion and worldviews; the way forward. A national plan for RE. Religious Education Council of England & Wales.

Drange, L. D. (2015). What does decolonisation mean in Bolivia in relation to the position of religion in the country’s new legislation and the new curriculum? Mission Studies, 32(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1163/15733831-12341382

Ford, D. (2013). Theology: A very short introduction (2nd ed.). Oxford Univ.

Giorda, M. C. (2015). Religious diversity in italy and the impact on education: The history of a failure. New Diversities, 17(1), 77–93.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (2003). Theory and reality: An introduction to the philosophy of science. The University of Chicago Press.

Gutting, G. (Ed.). (2005). Blackwell readings in continental philosophy Vol. 6: Continental philosophy of science. Blackwell.

Guzman, A., Imbarack, P., & Berrios, F. (2021). Formacion de Professores de Religion Catolica en Chile: Perfiles de Egreso y Configurazion de una Identitad Profesional. Revista Cultura & Religión, 15(1), 44–74.

Halafoff, A., Arweck, E., & Boisvert, D. (2016). Education about religions and worldviews: Promoting intercultural and interreligious understanding in secular societies. Routledge.

Helbling, D., & Riegel, U. (Eds.). (2021). Wirksamer Religions(kunde)unterricht. Schneider Verlag.

Jackson, R. (2007). Religion and education in Europe. Developments, contexts and debates. Waxmann.

Jung, M. H. (2004). Einführung in die Theologie. Einführung Theologie. WBG.

Kenngott, E.-M. (2017). Life design-ethics-religion studies: Non-confessional RE in Brandenburg (Germany). British Journal of Religious Education, 39(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2016.1218223

Kim, C. (2018). A critical evaluation of religious education in Korea. Religions, 9(11), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110369

Kropač, U. (2021). Religiöse Bildung. In U. Kropac & U. Riegel (Eds.), Handbuch Religionsdidaktik (pp. 17–28). Kohlhammer.

Kuyk, E., Jensen, R., Lankshear, D., Löh Manna, E., & Schreiner, P. (Eds.). (2007). Religious education in Europe: Situation and current trends in schools. IKO.

Lipiäinen, T., Ubani, M., Viinikka, K., & Kallioniemi, A. (2020). What does “new learning” require from religious education teachers? A study of Finnish RE teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Religious Education, 68(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-020-00098-3

Luhmann, N. (1992). Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft (Vol. 1001). Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, N. (Ed.). (2002). Das Erziehungssystem der Gesellschaft. Suhrkamp.

Lüscher, K., & Bronfenbrenner, U. (Eds.). (1981). Die Ökologie der menschlichen Entwicklung: Natürliche und geplante Experimente. Klett-Cotta.

Matemba, Y. (2021). Decolonising religious education in sub-Saharan Africa through the prism of anticolonialism: A conceptual proposition. British Journal of Religious Education, 43(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2020.1816529

Miedema, S. (2014). From religious education to worldview education and beyond: The strength of a transformative pedagogical paradigm. Journal for the Study of Religion, 27(1), 82–103.

Mokotso, R. (2020). New Lesotho integrated curriculum: The missed but not lost opportunity for decoloniality of Religious Education. Pharos: Journal of Theology, 101, 1–9.

Moore, D. L. (2007). Overcoming religious illiteracy: A cultural studies approach to the study of religion in secondary education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Riegel, U., & Rothgangel, M. (2023). Designing research in subject matter didactics. Results and open questions of a delphi study. RISTAL: Research in Subject-Matter Teaching and Learning, 5, 56–77.

Roebben, B. (2021). Religious education in Europe: Quo vadis? Unconventional thoughts in unconventional times. Religious Education, 116(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344087.2020.1839159

Rosenblith, S. (2017). Religion in schools in the United States. In S. Rosenblith (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education (pp. 1–17). Oxford University Press.

Rothgangel, M., Aslan, E., & Jäggle, M. (Eds.). (2020a). Religious education at schools in Europe: Southeastern Europe. V&R.

Rothgangel, M., Danilovich, Y., & Jäggle, M. (Eds.). (2020b). Religious education at schools in Europe: Eastern Europe. V & R.

Rothgangel, M., Jackson, R., & Jäggle, M. (Eds.). (2014). Religious Education at Schools in Europe. Volume 2: Western Europe. V&R.

Rothgangel, M., Rechenmacher, D., & Jäggle, M. (Eds.). (2020c). Religious education at schools in Europe: Southern Europe. V & R.

Rothgangel, M., Skeie, G., & Jäggle, M. (Eds.). (2014). Religious education at schools in Europe: Northern Europe. V & R.

Runkel, G., & Burkart, G. (Eds.). (2005). Funktionssysteme der Gesellschaft: Beiträge zur Systemtheorie von Niklas Luhmann. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Schweitzer, F., & Schreiner, P. (2020). International knowledge transfer in religious education: Universal validity or regional practices? Backgrounds, considerations and open questions concerning a new debate. British Journal of Religious Education, 42(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2019.1701987

Sprague, J. (2016). Feminist methodologies for critical researchers: Bridging differences (Second edition). Rowman & Littlefield.

Ubani, M., Rissanen, I., Poulter, S. (2019). Contextualising dialogue, secularisation and pluralism. Religion in Finnish public education (Vol. 40). Waxmann Verlag.

van der Kooij, J., de Ruyter, D. J., & Miedema, S. (2017). The merits of using “Worldview” in religious education. Religious Education, 112(2), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344087.2016.1191410

Weinberg, S. (2016). To explain the world: The discovery of modern science. Penguin Books.

Whitworth, L. (2020). Do I know enough to teach RE? Responding to the commission on religious education’s recommendation for primary initial teacher education. Journal of Religious Education, 68(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-020-00115-5

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests that are relevant to the content of this article to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riegel, U., Rothgangel, M. The impact of institutional context on research in religious education: results from an international comparative study. j. relig. educ. 71, 155–166 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-023-00202-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-023-00202-3