Highlights

-

A novel amide-based nonflammable electrolyte is proposed. The formation mechanism and solvation chemistry are investigated by molecular dynamics simulations and density functional theory.

-

An inorganic/organic-rich solid electrolyte interphase with an abundance of LiF, Li3N and Li–N–C is in situ formed, leading to spherical lithium deposition.

-

The amide-based electrolyte can enable stable cycling performance at room temperature and 60 ℃.

Abstract

The formation of lithium dendrites and the safety hazards arising from flammable liquid electrolytes have seriously hindered the development of high-energy-density lithium metal batteries. Herein, an emerging amide-based electrolyte is proposed, containing LiTFSI and butyrolactam in different molar ratios. 1,1,2,2-Tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropylether and fluoroethylene carbonate are introduced into the amide-based electrolyte as counter solvent and additives. The well-designed amide-based electrolyte possesses nonflammability, high ionic conductivity, high thermal stability and electrochemical stability (> 4.7 V). Besides, an inorganic/organic-rich solid electrolyte interphase with an abundance of LiF, Li3N and Li–N–C is in situ formed, leading to spherical lithium deposition. The formation mechanism and solvation chemistry of amide-based electrolyte are further investigated by molecular dynamics simulations and density functional theory. When applied in Li metal batteries with LiFePO4 and LiMn2O4 cathode, the amide-based electrolyte can enable stable cycling performance at room temperature and 60 ℃. This study provides a new insight into the development of amide-based electrolytes for lithium metal batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As fossil fuels continue to be depleted, the development of sustainable new energy is of great significance for social development [1, 2]. Lithium-ion battery technology has already proved its value in the 2019 Nobel Prize. However, to further expedite the application of EVs and reduce the usage of fossil fuels, commercial lithium-ion batteries having graphite anode still need improvements in energy density. Therefore, it is urgent to develop next-generation high-energy–density batteries [3]. Lithium metal has become one of the most promising anode materials, owing to its ultrahigh specific capacity (3860 mAh g−1) and lowest electrochemical potential (− 3.04 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode) [4, 5]. Despite these advantages, the development of practical lithium metal battery (LMB) is still hampered by issues like by low coulomb efficiency, Li dendrite growth and unstable solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layers [6,7,8]. The growth of Li dendrites can reduce coulomb efficiency and trigger short circuits within the cell, resulting in serious safety hazards [9, 10]. Lithium metal can react with the electrolyte to form an SEI layer on the interface. A stable SEI layer could prevent further decomposition of the electrolyte, while some an unstable SEI layer consumes the electrolyte during the battery cycling. Therefore, it is crucial to construct a stable SEI layer toward a superior battery performance [7, 11, 12].

Numerous strategies, such as artificial SEI structures, protective coating and electrolyte engineering (manipulating Li salts, solvent or additives), have been developed to regulate the electrochemical deposition of lithium [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Although artificial SEI design and protective coating can effectively inhibit the growth of Li dendrites, the tedious fabrication procedure and the drastically increased interfacial impedance originating from the formation of non-smooth thick layers further limit the practical prospect [23,24,25,26]. In comparison, optimizing the electrolyte becomes the most promising and facile approach owing to its easy operation for scale-up and low cost. For example, it has been reported that electrolyte engineering can enable the formation of Li3N layer and incorporation of Li–N–C groups on the surface of Li metal, which can serve as the Li-ion diffusion channels and inhibit Li dendrite growth [27,28,29,30].

As for lithium metal batteries, the commonly used electrolytes can be divided as carbonate-based electrolytes and ether-based electrolytes. However, carbonates have the disadvantages of flammability, volatility, poor thermal stability and easily causing lithium dendrites growth, while the low electrochemical oxidation potential of ethers limits their practical application [23, 31]. Therefore, it is urgent to develop a safe electrolyte having characteristics like nonflammability, preventing formation of lithium dendrites and good interfacial compatibility with lithium metal anode. Numerous works have been carried out to develop such a safe electrolyte. The researchers not only tried optimizing the conventional electrolytes, but also proposed various new concepts including super-concentration electrolyte [32], ionic liquids [33], polymer electrolyte [34] and solid-state electrolyte [35]. Among those proposed strategies, liquid electrolytes can have better wettability with electrode materials and greater ion transport ability. Therefore, it is desirable to design a new liquid electrolyte by electrolyte engineering, which can, at the same time, solve the issues of flammability and lithium dendrite growth in conventional electrolytes.

In this work, we propose a novel amide-based electrolyte composed of LiTFSI and butyrolactam (BL), which can keep a liquid state at room temperature. Meanwhile, we employed 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropylether (TTE) as a co-solvent to reduce the viscosity and improve the compatibility with the lithium metal. Besides, fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) was introduced as an additive to further stabilize the interfaces. With the above delicately designed electrolyte, a stable SEI layer with inorganic/organic-rich components (LiF, Li3N and Li–N–C) can be in situ formed, which can effectively regulate the morphology and structure of lithium to achieve its uniform deposition. The formation mechanism of the amide-based electrolyte and its ionic morphology are further elucidated by density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics simulations (MD simulations). The amide-based electrolyte shows good compatibility with lithium metal and exhibits superior cycling performance in Li||LFP and Li||LMO full cells. Moreover, the electrolyte can resist high temperatures (60 °C) and guarantee stable operation of batteries. The carefully designed amide-based electrolyte can also be extended to zinc-ion batteries and other metal-ion batteries. There is no doubt that this work can broaden the pathways for the future electrolyte development.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Electrolyte Preparation

Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI), butyrolactam (BL) and fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd. 1,1,2,2-Tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropylether (TTE) was provided by Dadao New Material Technology Co., Ltd.

The electrolytes were prepared by mixing different molar ratios of LiTFSI and BL with 5 wt% FEC at room temperature until a transparent solution was obtained. The obtained electrolyte was denoted as LB-x (x indicates the molar ratio of LiTFSI to BL is 1:x). Similarly, LBT electrolyte was prepared by mixing TTE and LB-3 electrolyte with various molar ratios, and the final electrolyte was denoted as LBT-x (x represents the molar ratio of TTE to LB-3). As a comparison, LB-3 and LBT-1 without FEC additive were denoted as LB-3 (without FEC) and LBT-1 (without FEC). All electrolytes were prepared in an Ar-filled glove box with the H2O/O2 concentration below 0.2 ppm.

2.2 Characterization

The viscosity of the as-prepared electrolytes was measured with an A&D SV-1A vibro-viscometer (A&D Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) at 25 °C. The ionic conductivity of amide-based electrolytes was tested on the conductivity meter (Leici 308F, Shanghai) at 25 °C. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed from room temperature to 600 ℃ with a heating rate of 10 ℃ min−1 under nitrogen atmosphere. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was tested by the IRTracer-100 spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan) at room temperature. The Raman spectra were carried out by using a Raman spectrometer (Horiba, LabRAM HR800, USA). The morphology of Li deposited on Cu substrate after 10 cycles in Li||Cu cells was observed by FE-SEM (HITACHI, SU8010, Japan). In situ optical microscope was characterized by in situ cell module under an optical microscope (Weiscope, WSP300D, China). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on a PHI 5000 VersaProbe II spectrometer with monochromatic Al Kα X-ray radiation.

The LiMn2O4 (LMO) and LiFePO4 (LFP) cathodes were prepared by a conventional slurry coating method. The LMO/LFP active materials, carbon black and polyvinylidene fluoride were dispersed well in a FA25 superfine homogenizer in a mass ratio of 80:10:10, with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone as the dispersant. The active materials mass loading of the cathode was 1.5–2.0 mg cm−2. Li chips were used as the anode and GF membranes (Whatman GF/A) as the separator. The oxidative stability of the electrolyte was tested by Li||SS cells from open circuit voltage to 6 V at a sweep rate of 1 mV s−1. The current response with different electrolytes was tested by CV in Li||Cu cell from -0.3 to 0.6 V. The charge and discharge tests were performed on the NEWARE BTS-51 battery test system at different temperatures with the voltage range of 2.5–4.2 V for LFP and 3.0–4.4 V for LMO. C rate is defined according to the theoretical capacities of LFP (170 mAh g−1) and LMO (117 mAh g−1). The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were tested in the frequency range from 106 to 10–2 Hz with a voltage amplitude of 10 mV. Cyclic voltammetry (CV), linear sweep Voltammetry (LSV) and EIS data were collected on a CHI 760E (CH, Shanghai, China) electrochemical workstation.

2.3 Computational Details

All the all-atom MD simulations were based on a general AMBER force field [36] with the RESP charges [37] and were carried out using the Gromacs-4.6.7 software package [38]. The system is a relaxed liquid configuration at 298 K. The total run time was 10 ns NPT for the equilibrium MD simulation. We used the relaxed system as a starting configuration. As it is prior to system relaxation MD, energy minimization was carried out with a composite protocol of steepest descent using termination gradients of 100. The Nose´–Hoover thermostat [39] was used to maintain the equilibrium temperature at 298 K and periodic boundary conditions were imposed on all three dimensions. The particle mesh Ewald method [40, 41] was used to compute long-range electrostatics within a relative tolerance of 1 × 10–6. A cutoff distance of 1 nm was applied to real-space Ewald interactions. The same value was used for van der Waals interactions. The LINCS algorithm [42] was applied to constrain bond lengths of hydrogen atoms. A leapfrog algorithm [43] was used with a time step of 2 fs. The molecular structure optimization was performed using Gaussian 03 program package with B3LYP/6-311G** level [44], and each molecular was checked to have minimum energy without imaginary frequency. Electrostatic potential (ESP) [45] analysis and reduced density gradient (RDG) [46] analysis were conducted using Multiwfn [47] and Winvmd [48].

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 New Amide-based Electrolyte and Physicochemical Properties

LiTFSI and butyrolactam (BL) can form homogenous and transparent liquids (LB) at ambient temperature when molar ratio is predetermined from 1:2 to 1:4 (denoted as LB-x, x = 2, 3 and 4). Adding TTE to the LB-3 electrolyte (denoted as LBT-x; x = 0, 0.5, 1 and 1.5) can reduce the lithium salt concentration and viscosity, while increasing the ion conductivity. The physical properties of the LB and LBT electrolytes with different molar ratios are shown in Fig. S1. Of all the LB samples, the LB-3 electrolyte with a molar ratio of 1:3 shows the highest ionic conductivity (0.43 mS cm−1 at room temperature) and relatively low viscosity (238.1 mPa s). Taking the high ionic conductivity into consideration, we chose LB-3 for the further experiments. The viscosity of LBT-1 reduces to 29.5 mPa s, while the ion conductivity (1.25 mS cm−1) increases to three times as that of the pure LB-3. The melting temperature of LBT-0 is 1.7 ℃, which is lower than that of individual LiTFSI (~ 234 ℃) or BL (~ 23 ℃). The temperature drops to -16.2 ℃ for LBT-1 with the addition of TTE (Fig. S2).

The good thermal stability of the electrolyte can ensure the battery safety when a short circuit or thermal runaway occurs during operation. The thermal behaviors of LB and LBT electrolytes with different compositions were studied by TGA (Fig. S3). The onset temperature for degradation of LB electrolytes is over 160 ℃. Furthermore, the weight losses are only about 1.2% (LB-2), 1.3% (LB-3) and 1.1% (LB-4) after heating at 100 °C, demonstrating the thermal stability of LB electrolytes in the operating temperature region. In contrast, pure BL decomposes from 50 ℃ and suffers a 78% weight loss after heating to 160 ℃, implying that there is an interaction between BL and LiTFSI, which alleviates the decomposition of BL. And there is a certain weight loss before 100 ℃ for LBT electrolytes, which should be ascribed to the volatile characteristics of TTE. Therefore, the good thermal stability of LBT electrolytes allows the battery to be operated at higher temperatures. Figure S3c shows the weight loss of TTE in pure TTE and LBT-1 electrolyte at 30 ℃, and the pure TTE undergoes a completely weight loss because of evaporation within 6 min. In contrast, the weight loss of TTE in LBT-1 maintains for 30 min because TTE has weak interaction with LB electrolyte, which suppresses the evaporation of TTE. This result is consistent with the DFT calculation (Figs. 1h and S10).

3.2 Solution Structure Analysis of LB and LBT Electrolyte

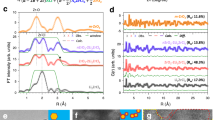

FTIR spectrum and Raman spectra were used to analyze the formation mechanism of amide-based electrolyte. For LB electrolytes, the FTIR bands at 1670 cm−1 assigned to C = O of BL and 747 cm−1 assigned to TFSI− shift to 1657 and 739 cm−1, respectively, after solution formation (Fig. 1a), which resulting from the strong coordination interaction between Li+ and C = O of BL [49]. Upon introduction of LiTFSI, the band at 3230 cm−1, originating from BL’s NH stretching vibration, almost disappears (Fig. S4), indicating that BL does not exist as free solvent molecules [50]. Similar results can be also obtained from Raman spectra (Fig. 1b). Two obvious spectra changes appear from 3275 to 3396 cm−1 and from 1658 to 1681 cm−1, corresponding to NH stretching and C = O stretching of BL in the composite, respectively. The bands at 1248 and 1131 cm−1 are attributed to SO2 stretching and CF3 symmetric stretching of solid LiTFSI, respectively [51], and they shift to 1243 and 1138 cm−1 upon the addition of BL into LiTFSI. These results reveal that the spectral bands associated with the C = O and NH vibration of BL and the SO2 and CF3 vibration of LiTFSI change significantly when a homogeneous liquid is formed due to Li+ cations coordinated C = O of BL while NH interacts with SO2 group of TFSI−. The DFT optimized structure also confirms the interaction between -NH and S = O of TFSI− (Fig. S9). The intermolecular interactions between LiTFSI and BL jointly weaken the individual bonds of original compositions and promote the separation of cations and anions, resulting in liquid state [50], as illustrated in Fig. 1f. For LBT electrolytes, the IR bands at 1180 cm−1 of TFSI− and 1656 cm−1 of BL slightly change (Fig. S5). Figure 1c shows that two characteristic Raman peaks at 858 and 838 cm−1 assigned to TTE shift to 832 and 817 cm−1, respectively [52], and the band of BL shift from 900 to 890 cm−1 when introducing TTE into LB electrolyte (Fig. S6), owing to the weak interaction between TTE and LB.

a FTIR spectra of LB electrolytes at different compositions. Raman spectra of b LB electrolytes and c LBT electrolytes at different compositions. d Fitted Raman spectra of LB electrolytes and LBT-1 in the range of 730–760 cm−1. The experimental spectra and fitted curves are denoted by the solid and dashed lines, respectively. e Solvate species distribution in LB electrolytes and LBT-1 determined by fitted Raman spectra. f Schematic diagram of LiTFSI and BL forming a liquid. Gradient isosurfaces (s = 0.5 au) for i LiTFSI-BL and j LiTFSI-BL-TTE. ESPs mapped on electron total density for k LiTFSI-BL and l LiTFSI-BL-TTE

It has been confirmed that the Raman peaks at around 720–760 cm−1 can be attributed to the free and Li-bond TFSI anion [53, 54]. As shown in Fig. 1d, the peaks at 741, 745 and 749 cm−1 corresponding to free anions (FA, TFSI− coordinating 0 Li+), contact ion pairs (CIP, TFSI− coordinating 1 Li+) and aggregate clusters (AGG, TFSI− coordinating 2 Li+ or more Li+), respectively. The decrease in the lithium salt concentration with the increase in the BL leads to a decrease in the proportion of AGG while the FA content increases (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, the existence of TTE in BL electrolyte can also result in an increase in the proportion of free TFSI−, which indicates that TTE is beneficial to the dissociation of Li+ and TFSI−.

MD simulation was carried out to further understand the solvation structure of amide-based electrolytes and the effect of introducing TTE. Figure 2a–d shows the snapshots of LB-2, LB-3, LB-4 and LBT-1. The results of radial distribution function and coordination numbers for simulated electrolytes are demonstrated in Fig. S7. Two sharp peaks of Li-OBL and Li-OTFSI are observed at 1.97 and 2.02 Å for all studied electrolytes. This indicates that Li-OBL and Li-OTFSI are used as first coordinated shell (2.80 Å within Li+ cations). And Li-NTFSI, Li-NBL and Li-OTTE are far away from Li+ about 4 Å, which means that they are barely coordinated with Li+. With the increase in the BL content and the introduction of TTE, the coordination number of Li+ and TFSI- decreases, which is conducive to the dissociation of Li+ and TFSI- (Table S1). The molecular structures of LiTFSI, BL and TTE and corresponding atomic charge for MD simulations are shown in Fig. S8. The detailed results obtained from MD simulations are listed in Tables S1.

AIMD simulation snapshots of a LB-2, b LB-3, c LB-4 and d LBT-1 at 298 K. Ball and stick model stand for LiTFSI, while BL (blue) and TTE (green) are presented by wireframes. Representative Li+ coordination structure in e LB-2, f LB-3, g LB-4 and h LBT-1. Percentage of Li+ coordination structure in different electrolytes based on MD simulation. i Percentage of Li+ cations coordinated with different number of TFSI− anions in LB-2, LB-3, LB-4 and LBT-1. j Percentage of Li+ cations coordinated with different number of BL molecules in LB-2, LB-3, LB-4 and LBT-1(O = represents the O atom in BL)

The statistics of MD simulation are shown in Fig. 2 and Table S1. In LB-2 and LB-3 electrolytes, Li+ tends to coordinate with two TFSI− anion (two O atoms from two SO2 groups of TFSI− anion). When the content of BL is increased for LB-4 and TTE is added for LBT-1, Li+ tends to coordinate with 3 TFSI− anion (only one O atom from one SO2 group of TFSI− anion). This result indicates that BL can facilitate the dissociation between Li+ and TFSI− due to the strong coordination between Li+ and O = of BL. Meanwhile, the addition of TTE into LB electrolytes can also achieve the same result. This is a mutual verification with the peak fitting results of Raman characterizations.

DFT was performed to further investigate the coordination structure between LiTFSI and BL, and the optimized structures of different numbers of LiTFSI and BL are shown in Fig. S9. The energy is the lowest when Li+ is coordinated to two oxygen atoms on different -SO2 groups on the central nitrogen. The preference for 5-coordinate Li+ can be seen from the optimization results when one Li+/TFSI− ion pairs with BL molecules from one to four. The optimized structure of LB-2 with four coordinates still allows more BL molecules to coordinate with the Li+ cation. With the introduction of BL molecules, the distance between Li+ and the sulfonyl oxygen atom of TFSI− increases. Furthermore, Li+ coordinates with only one oxygen atom of one sulfonyl group with the number of BL above two. These results indicate that the strong coordination between BL and Li+ promotes the dissociation between Li+ and TFSI−, which is consistent with the MD simulations results. Reduced density gradient (RDG) analysis is an effective method for visually characterizing the regions and types of molecular weak interactions, including the van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds and spatial repulsion [55]. As displayed in Fig. 1g, h and S10, a strong coordination bond exists between Li+ and the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group and sulfonyl groups. In addition, there are also significant van der Waals interaction between BL and TFSI− anion, similar to the DFT results. Figure 1i, j and S11 reveal the electron density of LB system by ESP analysis. The mutual attraction between the negatively electronegativity region of BL around the oxygen atoms and the positively charged regions around Li+ leads to the formation of a stable structure [56].

The interfacial compatibility of lithium metal and electrolyte is further investigated by symmetric Li||Li cells. Figure S12 shows the cycle performance of Li||Li symmetric cells under 0.2 mA cm−2. The cell with LBT-0 electrolyte shows obvious voltage fluctuation after 50 h and short circuit after 230 h; in contrast, the LBT-1 electrolyte can maintain stable cycling for more than 400 h, indicating LBT-1 electrolyte has better compatibility with lithium metal and more stable Li/electrolyte interface. The Coulomb efficiency was further examined by electrochemical testing of Li||Cu cells (Fig. S13). The 1 M LiPF6 EC-DEC electrolyte shows average CE of only 76.9%; in contrast, LBT-1 electrolyte has a better CE of 86.6%.

The stable electrochemical windows of all as-prepared electrolytes were tested using linear scanning voltammetry (LSV). As shown in Fig. S14, the anodic oxidation potential of all electrolytes is up to 4.7 V defined at 10 μA cm−2, which can be compatible with electrode materials working at a relatively high voltage. Furthermore, the influence of introducing TTE into LB electrolytes on the electrochemical window can be ignored. The current response in LBT-1 increases significantly during Li plating/stripping on Cu electrode, indicating the rapid Li+ transport and more reversible reaction kinetics (Fig. S15) [57].

3.3 Spherical Li Deposition and In situ Observation of Li Plating

The morphology of Li deposition on Cu substrate in different electrolytes is presented in Fig. 3. In conventional carbonate-based electrolyte (1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC), a large number of irregular Li dendrites can be clearly observed. The needlelike dendritic structure at the tip may penetrate through the separator and cause an internal short circuit, leading to serious safety risks. The growth of dendrites in carbonate-based electrolyte is mainly attributed to the low Li+ conductivity and uneven Li+ flux of SEI film formed by conventional organic solvents (Fig. 3a, c, d). On the contrary, the spherical Li deposition occurred in both LBT-0 and LBT-1 electrolytes. This result indicates a uniform and stable SEI film formed with high Li+ conductivity and uniform spatial distribution of Li+, resulting in spherical lithium deposition (Fig. 3b, g, h).

Schematic illustration of the Li plating behavior with different electrolytes: a 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC and b amide-based electrolytes. SEM images of Li metal after plating on Cu foil at 0.2 mA cm−2 with a capacity of 0.4 mAh cm−2 in different electrolytes: c-d 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC (1:1, v/v), e–f LBT-0 and g-h LBT-1

In order to visualize the morphology evolution of Li deposition at the electrolyte/electrode interface, in situ optical microscope was performed on the cells with different electrolytes. As shown in Fig. 4, the pristine Li electrode was smooth and flat before Li plating. For the carbonate-based electrolyte, a mosslike Li dendrites appeared as early as 2 min after Li plating, and the growth of Li dendrites boomingly evolved as time went on. In comparison, a dense and more uniform Li deposition with almost no dendritic structure was obtained with LBT-1 electrolyte. This observation indicates that LBT-1 electrolyte can effectively suppress the formation of Li dendrites and is desirable for the practical application of lithium metal batteries. The dynamic morphology evolution of Li deposition is consistent with SEM results.

3.4 Chemical Composition Analysis of SEI Layer

Chemical compositions of the SEI surface were further investigated on the cycled Li metal anodes by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) comparing amide-based electrolytes (Fig. 5) and conventional EC/DEC electrolyte (Fig. S16). The survey spectra are displayed in Fig. S17. In C 1s spectra, the signals of C–C/C–H (284.8 eV), C–O (286.3 eV) and CO32− (289.0 eV) can be detected in both LBT-0 and LBT-1 electrolytes [57]. In contrast, two additional peaks corresponding to C–SOx (287.4 eV) [58] and C–Fx (292.8 eV) [59] appear with the introduction of TTE, probably resulting from the decomposition of TFSI− anions. The signals of C–Fx (688.7 eV) are further confirmed from F 1s spectra, and the other peak can be assigned to LiF (685.0 eV), which indicates the preferred reduction of FEC [60]. The peaks of LiF and C–F can also be observed in EC/DEC electrolyte. For the Li 1s spectra of EC/DEC electrolyte, the peaks around 55.4 and 56.4 eV can be attributed to the inorganic species of Li2CO3 and LiF [61]. For LBT-0 and LBT-1 electrolytes, the signals of Li2CO3 (54.2 eV), Li3N (55.0 eV) and LiF (56.4 eV) can be detected [27, 62]. On the contrast, one more peak at 57.9 eV corresponds to organic species (such as Li–N–C) after the addition of TTE, originating from the decomposition of BL and LiTFSI [63]. This result demonstrates that TTE can regulate the chemical composition of SEI by affecting the solvation structure of electrolyte. The organic species Li–N–C and the inorganic species (including LiF and LiN) jointly dominate the SEI chemistry in LBT-1. These Li–N species can be further validated by N 1s spectra (Fig. 5d), where the signals of Li3N (398.6 eV), N–SOx (400.0 eV) and Li–N–C (402.2 eV) can be clearly observed [63]. However, Fig. S16c reveals the absence of N species in EC/DEC electrolytes. In addition, the atomic content of F and N in the SEI film formed in LBT-1 is much higher than that in LBT-0 and EC/DEC electrolytes (Fig. S18). Consequently, the SEI film contains abundant inorganic species (LiF and Li3N) and organic species (C–N, S–N, and C–S) [29]. The inorganic/organic-rich SEI film possesses high ionic conductivity and high interface energy, which can synergistically regulate the nucleation of Li, contributing to the uniform and rapid lithium deposition and resulting in spherical Li deposition.

3.5 Highly Stable LMBs with LiFePO4 (LFP) and LiMn2O4 (LMO) Cathodes

The potential application and feasibility of amide-based electrolytes were further evaluated in LFP||Li and LMO||Li full cells. The rate performance of LFP||Li cell was evaluated in two electrolytes from 0.1 to 2 C (Fig. 6a). The LBT-1 electrolyte demonstrates better rate performance compared to the LBT-0 electrolyte. The specific capacities of LBT-1 electrolyte are 155.5, 150.6, 136.9, 124.8, 99.1 mAh g−1 at the current densities of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1 and 2 C, respectively. Figure 6b displays that the long-term cycling performance of LBT-0 and LBT-1 electrolytes at 1 C and room temperature (~ 22 ℃). The cell with LBT-1 electrolyte exhibits outstanding cycling performance, remaining a capacity retention of 89% after 650 cycles. In contrast, the cell using LBT-0 electrolyte suffers from severe capacity fading, only remaining a capacity retention of 35% after 200 cycles. And the cell with carbonate electrolyte has a higher initial discharge capacity compared to the LBT electrolytes, but only maintains a capacity retention of 60% after 650 cycles at 1 C (Fig. S19a). Since TTE has a high boiling point (92 ℃) and LB electrolytes show superior thermal stability over 160 ℃, the LBT electrolytes with TTE also support operation at higher temperatures. As shown in Fig. 6c, the capacity of LFP with LBT-1 electrolyte still maintains 87% at 60 ℃ after 150 cycles. In comparison, the capacity of LBT-0 electrolyte declines sharply to 13% at 60 ℃. The introduction of TTE can reduce the viscosity, increase the conductivity and improve the compatibility with lithium metals simultaneously. The compatibility of amide-based electrolytes to the high-voltage LMO cathode was also evaluated in an LMO||Li full cell. As shown in Fig. S20, LBT-1 electrolyte exhibits an initial specific capacity of 106.6 mAh g−1 with 89% capacity retention after 100 cycles at 0.2 C from 3.0 to 4.4 V, which is better than LBT-0 electrolyte with an initial specific capacity of 90.2 mAh g−1. In comparison, there is only 66.2% capacity retention for LMO||Li cell using carbonate electrolyte at 0.2 C after 100 cycles (Fig. S19b). To clarify the role of FEC additive, the cycling performance of LB-3 (without FEC) and LBT-1 (without FEC) was compared (Fig. S21). The cycling performance of both LB-3 (without FEC) and LBT-1 (without FEC) decays rapidly, indicating that FEC as a SEI film-forming additive is critical for improving battery performance. These results indicate that both FEC and TTE contribute to outstanding cycling performance. The typical charge–discharge profiles of Li||LFP cell and Li||LMO cell at different cycles of amide-based electrolytes and carbonate electrolyte are shown in Figs. S22 and S23, which indicates that the polarization of the LBT-0 electrolyte increases sharply with increasing cycles. Figure S24 shows the voltage profiles of two electrolytes at various currents and potential gaps of the first cycle at 0.1 C, indicating a significant decrease in polarization of LBT-1. The lower polarization can be attributed to the lower viscosity and faster lithium-ion migration rate through the organic/inorganic-rich SEI due to the existence of Li–N–C, LiF and Li3N. The excellent performance of LBT-1 electrolyte should be attributed to its higher ionic conductivity, inorganic/organic-rich stable SEI, better kinetics and lower polarization. In addition, the dendrite-free Li deposition also contributes to its superior performance. Notably, both LBT-0 and LBT-1 electrolytes are nonflammable and offer good safety in case of battery fire or explosion. In contrast, commercial EC-DEC electrolytes are inherently flammable, which limits their applications in future batteries (Fig. 7).

4 Conclusion

In summary, a new type of amide-based nonflammable electrolyte has been successfully designed to significantly improve the safety and recyclability of lithium metal batteries. The introduction of TTE reduces the viscosity while improving the interfacial compatibility with lithium metal. Furthermore, the in situ formation of inorganic/organic-rich SEI layer consisting of LiF, Li3N and Li–N–C enables the uniform and rapid deposition of Li+, resulting in spherical lithium deposition. As a result, a lithium metal battery with LFP cathode displays very reliable cyclability and achieves an 89% capacity retention after 650 cycles. The cells can also operate stably even at 60 °C. Notably, the amide-based electrolyte possesses excellent electrochemical stability (> 4.7 V), providing another option for the application of high-voltage electrode materials. We are convinced that this work will provide a facile and effective strategy to alleviate the critical issues of lithium metal anodes, providing a deep insight into the development of highly safe, dendrite-free and durable lithium metal batteries.

References

S. Chu, A. Majumdar, Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11475

S. Chu, Y. Cu, N. Liu, The path towards sustainable energy. Nat. Mater. 16, 16–22 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4834

J. Janek, W.G. Zeier, A solid future for battery development. Nat. Energy 1, 16141 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.141

X.B. Cheng, R. Zhang, C.Z. Zhao, Q. Zhang, Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: a review. Chem. Rev. 117, 10403–10473 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00115

H. Wang, R. Tan, Z. Yang, Y. Feng, X. Duan et al., Stabilization perspective on metal anodes for aqueous batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2000962 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202000962

C. Fang, X. Wang, Y.S. Meng, Key issues hindering a practical lithium-metal anode. Trends Chem. 1, 152–158 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2019.02.015

J. Zhu, P. Li, X. Chen, D. Legut, Y. Fan et al., Rational design of graphitic-inorganic Bi-layer artificial SEI for stable lithium metal anode. Energy Storage Mater. 16, 426–433 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.06.023

C. Cui, C. Yang, N. Eidson, J. Chen, F. Han et al., A highly reversible, dendrite-free lithium metal anode enabled by a lithium-fluoride-enriched interphase. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906427 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201906427

R. Xu, X.Q. Zhang, X.B. Cheng, H.J. Peng, C.Z. Zhao et al., Artificial soft-rigid protective layer for dendrite-free lithium metal anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1705838 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201705838

L. Yang, Y. Song, H. Liu, Z. Wang, K. Yang et al., Stable interface between lithium and electrolyte facilitated by a nanocomposite protective layer. Small Methods 4, 1900751 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.201900751

D. Kang, N. Hart, J. Koh, L. Ma, W. Liang et al., Rearrange sei with artificial organic layer for stable lithium metal anode. Energy Storage Mater. 24, 618–625 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2019.06.014

X. Liu, Z. Xu, A. Iqbal, M. Chen, N. Ali et al., Chemical coupled PEDOT: PSS/Si electrode: suppressed electrolyte consumption enables long-term stability. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00564-5

S. Liu, X. Ji, N. Piao, J. Chen, N. Eidson et al., An inorganic-rich solid electrolyte interphase for advanced lithium-metal batteries in carbonate electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3661–3671 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202012005

S. Li, Z. Luo, L. Li, J. Hu, G. Zou et al., Recent progress on electrolyte additives for stable lithium metal anode. Energy Storage Mater. 32, 306–319 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2020.07.008

D. Luo, L. Zheng, Z. Zhang, M. Li, Z. Chen et al., Constructing multifunctional solid electrolyte interface via in-situ polymerization for dendrite-free and low n/p ratio lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 12, 186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20339-1

P. Zhai, L. Liu, X. Gu, T. Wang, Y. Gong, Interface engineering for lithium metal anodes in liquid electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001257 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202001257

X. Yang, M. Jiang, X. Gao, D. Bao, Q. Sun et al., Determining the limiting factor of the electrochemical stability window for PEO-based solid polymer electrolytes: main chain or terminal –OH group? Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 1318–1325 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ee00342e

J. Bae, Y. Qian, Y. Li, X. Zhou, J.B. Goodenough et al., Polar polymer–solvent interaction derived favorable interphase for stable lithium metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 3319–3327 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ee02558h

Q. Liu, Y. Xu, J. Wang, B. Zhao, Z. Li et al., Sustained-release nanocapsules enable long-lasting stabilization of Li anode for practical Li-metal batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 176 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00514-1

T. Liu, J. Wang, Y. Xu, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, Dendrite-free and stable lithium metal battery achieved by a model of stepwise lithium deposition and stripping. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 170 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00687-3

S. Zhang, Suppressing Li dendrites via electrolyte engineering by crown ethers for lithium metal batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 158 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00501-6

L. Zheng, F. Guo, T. Kang, Y. Fan, W. Gu et al., Stable lithium-carbon composite enabled by dual-salt additives. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 111 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00633-3

H. Wu, H. Jia, C. Wang, J.G. Zhang, W. Xu, Recent progress in understanding solid electrolyte interphase on lithium metal anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003092 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202003092

J.I. Lee, G. Song, S. Cho, D.Y. Han, S. Park, Lithium metal interface modification for high-energy batteries: approaches and characterization. Batter Supercaps 3, 828–859 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/batt.202000016

H. Zhou, S. Yu, H. Liu, P. Liu, Protective coatings for lithium metal anodes: recent progress and future perspectives. J. Power Sources 450, 227632 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.227632

C. Wang, T. Wang, L. Wang, Z. Hu, Z. Cui et al., Differentiated lithium salt design for multilayered PEO electrolyte enables a high-voltage solid-state lithium metal battery. Adv. Sci. 6, 1901036 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201901036

X.Q. Zhang, X. Chen, X.B. Cheng, B.Q. Li, X. Shen et al., Highly stable lithium metal batteries enabled by regulating the solvation of lithium ions in nonaqueous electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5301–5305 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201801513

F. Li, J. He, J. Liu, M. Wu, Y. Hou et al., Gradient solid electrolyte interphase and lithium-ion solvation regulated by bisfluoroacetamide for stable lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 6600–6608 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202013993

S. Ye, L. Wang, F. Liu, P. Shi, H. Wang et al., g-C3N4 derivative artificial organic/inorganic composite solid electrolyte interphase layer for stable lithium metal anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2002647 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202002647

H. Wu, Y. Xu, X. Ren, B. Liu, M.H. Engelhard et al., Polymer-in- “quasi-ionic liquid” electrolytes for high-voltage lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1902108 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201902108

S. Li, M. Jiang, Y. Xie, H. Xu, J. Jia et al., Developing high-performance lithium metal anode in liquid electrolytes: challenges and progress. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706375 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201706375

O. Borodin, J. Self, K.A. Persson, C. Wang, K. Xu, Uncharted waters: super-concentrated electrolytes. Joule 4, 69–100 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2019.09.022

Z. Wang, F. Zhang, Y. Sun, L. Zheng, Y. Shen et al., Intrinsically nonflammable ionic liquid-based localized highly concentrated electrolytes enable high-performance Li-metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003752 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202003752

K. Pan, L. Zhang, W. Qian, X. Wu, K. Dong et al., A flexible ceramic/polymer hybrid solid electrolyte for solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 32, 2000399 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202000399

A. Manthiram, X. Yu, S. Wang, Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.103

J. Wang, R.M. Wolf, J.W. Caldwell, P.A. Kollman, D.A. Case, Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20035

C.I. Bayly, P. Cieplak, W. Cornell, P.A. Kollman, A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 10269–10280 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1021/j100142a004

B. Hess, C. Kutzner, D.V.D. Spoel, E. Lindahl, Gromacs 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1021/ct700301q

Berendsen HJ, Gunsteren WFV (1986) Practical algorithms for dynamic simulations. Molecular-dynamics Simulation of Statistical-mechanical Systems 43–65

U. Essmann, L. Perera, M.L. Berkowitz, T. Darden, H. Lee et al., A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.470117

L.G. Astrakas, C. Gousias, M. Tzaphlidou, Structural destabilization of chignolin under the influence of oscillating electric fields. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 074702 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3699389

B. Hess, H. Bekker, H.J. Berendsen, J.G. Fraaije, Lincs: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12%3c1463::AID-JCC4%3e3.0.CO;2-H

W.F.V. Gunsteren, H.J. Berendsen, A leap-frog algorithm for stochastic dynamics. Mol. Simulat. 1, 173–185 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1080/08927028808080941

M. Frisch, G. Trucks, H. Schlegel, G. Scuseria, M. Robb et al., Gaussian (Gaussian Inc, Wallingford, 2004)

T. Lu, F. Chen, Quantitative analysis of molecular surface based on improved marching tetrahedra algorithm. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 38, 314–323 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2012.07.004

E.R. Johnson, S. Keinan, P. Mori-Sánchez, J. Contreras-García, A.J. Cohen et al., Revealing noncovalent interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6498–6506 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja100936w

T. Lu, F. Chen, Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.22885

W. Humphrey, A. Dalke, K. Schulten, VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5

R. Chen, F. Wu, L. Li, B. Xu, X. Qiu et al., Novel binary room-temperature complex system based on LiTFSI and 2-oxazolidinone and its characterization as electrolyte. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 5184–5194 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp066429f

H. Qiu, X. Du, J. Zhao, Y. Wang, J. Ju et al., Zinc anode-compatible in-situ solid electrolyte interphase via cation solvation modulation. Nat. Commun. 10, 5374 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13436-3

D. Brouillette, D.E. Irish, N.J. Taylor, G. Perron, M. Odziemkowski et al., Stable solvates in solution of lithium bis (trifluoromethylsulfone) imide in glymes and other aprotic solvents: phase diagrams, crystallography and Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 4, 6063–6071 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1039/B203776A

N. Piao, X. Ji, H. Xu, X. Fan, L. Chen et al., Countersolvent electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903568 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201903568

G. Yang, C. Chanthad, H. Oh, I.A. Ayhan, Q. Wang, Organic–inorganic hybrid electrolytes from ionic liquid-functionalized octasilsesquioxane for lithium metal batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 18012–18019 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta04599a

S. Lee, K. Park, B. Koo, C. Park, M. Jang et al., Safe, stable cycling of lithium metal batteries with low-viscosity, fire-retardant locally concentrated ionic liquid electrolytes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003132 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202003132

Z. Pan, Y. Bo, Y. Liang, B. Lu, J. Zhan et al., Intermolecular interactions in natural deep eutectic solvents and their effects on the ultrasound-assisted extraction of artemisinin from Artemisia annua. J. Mol. Liq. 326, 115283 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115283

X. Zhao, G. Zhu, L. Jiao, F. Yu, C. Xie, Formation and extractive desulfurization mechanisms of aromatic acid based deep eutectic solvents: an experimental and theoretical study. Chemistry 24, 11021–11032 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201801631

N.W. Li, Y. Shi, Y.X. Yin, X.X. Zeng, J.Y. Li et al., A flexible solid electrolyte interphase layer for long-life lithium metal anodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1505–1509 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201710806

S. Jiao, X. Ren, R. Cao, M.H. Engelhard, Y. Liu et al., Stable cycling of high-voltage lithium metal batteries in ether electrolytes. Nat. Energy 3, 739–746 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-018-0199-8

D. Ensling, M. Stjerndahl, A. Nytén, T. Gustafsson, J.O. Thomas, A comparative XPS surface study of Li2FeSiO4/C cycled with LiTFSI- and LiPF6-based electrolytes. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 82–88 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1039/b813099j

X.Q. Zhang, X.B. Cheng, X. Chen, C. Yan, Q. Zhang, Fluoroethylene carbonate additives to render uniform li deposits in lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1605989 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201605989

C. Yan, Y.X. Yao, X. Chen, X.B. Cheng, X.Q. Zhang et al., Lithium nitrate solvation chemistry in carbonate electrolyte sustains high-voltage lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14055–14059 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201807034

J. Fu, X. Ji, J. Chen, L. Chen, X. Fan et al., Lithium nitrate regulated sulfone electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 22378–22385 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202009575

Q. Wang, Z. Yao, C. Zhao, T. Verhallen, D.P. Tabor et al., Interface chemistry of an amide electrolyte for highly reversible lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 11, 4188 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17976-x

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21905069, 52002094), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (JCYJ20180507183907224, KQTD20170809110344233), the Economic, Trade and Information Commission of Shenzhen Municipality through the Graphene Manufacture Innovation Center (201901161514), the Guangdong Province Covid-19 Pandemic Control Research Fund (2020KZDZX1220) and the School Research Startup Expenses of Harbin Institute of Technology (Shenzhen) (DD29100027).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, W., Bo, Y., Li, D. et al. Safe and Stable Lithium Metal Batteries Enabled by an Amide-Based Electrolyte. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 44 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00780-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00780-7