Abstract

In this paper, I discuss the dark side of the cascading compliance model predominantly used by multinationals to improve working conditions in global value chains. Further, I discuss the origins of such dark side. Finally, I argue for the move from cascading compliance to a shared responsibility model for the improvement of working conditions in global value chains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Cascading compliance model: a rationale

Private governance mechanisms such as social auditing, codes, sustainability standards, and certifications have emerged as tools essential to improve working conditions in global value chains (GVCs). However, while these mechanisms have influenced tier-one suppliers, they have failed to affect lower-tier ones (Anner, 2020; Gold et al., 2015; Soundararajan & Brammer, 2018; Villena & Gioia, 2018). As a result, it is common for workers in the lower tiers of GVCs to operate under unsafe and unfair working conditions. Both research and practice have identified a range of labor abuses perpetrated in lower tiers, including physical and sexual violence, manipulation, forced overtime, the withholding of wages, debt bondage, forms of what amounts to physical imprisonment, the blacklisting of workers who speak out against mistreatment, and poor health and safety controls on production premises (Crane et al., 2019; LeBaron, 2021).

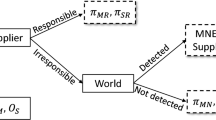

Lower-tier suppliers are not in direct contractual relationships with Multinational Enterprises (MNEs), which cannot therefore impose compliance demands on them (Grimm et al., 2016). This has resulted in MNEs adopting a cascading compliance model. In this approach, MNEs shift the responsibility of monitoring to tier-one suppliers or trade intermediaries like sourcing agents, with whom they are directly related (Narula, 2019; Soundararajan et al., 2018a). These supply chain actors are expected to act as double agents in ensuring their own compliance as well as that of their suppliers (Wilhelm et al., 2016).

Research has investigated ways MNEs can effectively use a cascading compliance model. For example, by means of an in-depth case study research, Wilhelm et al. (2016) identified the importance of incentives for tier-one suppliers and the existence of information symmetry between MNEs and tier-one suppliers. They also uncovered various contingency factors such as lead firm power, the resource availability of tier-one suppliers, and the internal alignment of purchasing and sustainability functions. As a result of a qualitative study on fashion GVCs, we found that sourcing agents can help lead firms cascade compliance under certain conditions, including knowledge about the relevant fields and actors, legitimacy in the relevant fields and the opinion of the parties involved, the effective translation of the expectations of each party to the other, and satisfactory incentives (Soundararajan et al., 2018a). In another study (Soundararajan & Brammer, 2018), we found evidence for the importance of framing, procedural fairness, and reciprocity. We found that lower-tier suppliers reciprocate positively when their tier-one counterparts or sourcing agents frame the compliance requirements as opportunities and offer support. In contrast, lower-tier suppliers reciprocate negatively when the compliance requirements are framed as a risk aversion mechanism and no support is offered.

In the rest of the paper, I will discuss the dark side of the cascading compliance model and its origins, and suggest ways to move towards a shared responsibility model. The arguments presented in this paper are based on my extensive research on fashion GVCs, India’s largest knitwear export industrial cluster in Tamil Nadu, as well as on literature and reports.

2 The dark side of the cascading compliance model

Given its prevalence, the focus of the extant studies has hitherto been on how to make the cascading compliance model work. However, there is a dark side to such model, which these studies have not explored: the practices that MNEs and tier-one suppliers adopt to make the cascade compliance model work can perpetuate exploitation and reproduce inequalities.

2.1 The perpetuation of exploitation

The cascading compliance model can lead to the perpetuation of exploitation by reducing supply chain transparency and increasing evasion.

The cascading compliance pressure applied by MNEs can lead to tier-one suppliers reducing supply chain transparency by not listing their sub-suppliers (LeBaron, 2021; Soundararajan et al., 2018b). By doing so, they avoid having to engage in any efforts or to divert any resources toward compliance. Research and reports have asserted that hidden supply chains are where the most horrific labor abuses happen (Villena & Gioia, 2018). MNEs do not have the local capabilities needed to track down hidden supply chains, and the local authorities of many developing economies do not scrutinize them. As a result, the labor rights violations occurring in lower tiers are perpetuated.

Further, greater monitoring responsibility means that, in order to secure orders from MNEs, tier-one suppliers need to produce their compliance certifications and those of their listed suppliers. However, obtaining compliance certificates is an added burden on the resources of lower-tier suppliers, which already benefit from a small share of the value generated in GVCs (Fontana & Egels-Zandén, 2019). Thus, tier-one suppliers often work with or help their listed lower-tier suppliers to produce false compliance. For example, I have found that they teach their lower-tier suppliers how to train workers for auditing. In addition, they use their social capital to get approvals for lower-tier suppliers from local authorities and, at times, bribe local authorities for lower-tier suppliers. Consequently, the exploitation of workers in lower-tier facilities is perpetuated.

2.2 The reproduction of inequalities

The cascading compliance model reproduces inequalities by pushing MNEs to avoid suppliers from marginalized societies and tier-one suppliers to act adversarially toward lower tiers and form dominant coalitions.

To reduce the risks involved in the cascading compliance model, MNEs may avoid working with suppliers from the most vulnerable and marginalized societies altogether (Narula, 2019). Such suppliers tend to be resource-deprived and to lack the capabilities to comply and/or help MNEs to ensure cascade compliance. So, by totally avoiding them, MNEs can prevent the risks involved in cascading compliance. In this respect, they can also compel tier-one suppliers to refrain from working with lower-tier ones from the most vulnerable and marginalized societies to reduce risks.

When tier-one suppliers stop working with lower-tier ones (Narula, 2019), local economic and gender inequalities can be reproduced. A 2021 ILOFootnote 1 report documented that developed countries account for 18. % of the informal sector, whereas developing countries account for at least 69.6% of it. In countries such as India, the informal sector has been found to account for around 93% of the economy. The first tier suppliers may be formal, but the lower tier ones predominantly comprise informal enterprises that face various challenges in improving compliance (Soundararajan & Brammer, 2018). First, they are resource-deprived and lack capabilities. Second, they depend on tier-one suppliers and trade intermediaries such as sourcing agents, and they gain very little for their participation in GVCs. Third, they face uncertainties in securing production orders and must compete fiercely to acquire them. Fourth, they must navigate weak institutional and market arrangements on a daily basis with whatever is at hand to run their business. All of this means that they struggle to strike a balance between survival and compliance. Removing any lower-tier suppliers without taking their challenges into account can easily make the cascading compliance model work, but it can also ruin the informal entrepreneurs and the workers who rely on them for survival. A large proportion of employment relationships in developing countries are informal, and many involve women. In many patriarchal societies, the informal sector offers women the flexibility they need to balance work and family life. So, the cascading compliance model can create or reproduce gender and economic inequalities (Van Assche & Narula, 2022).

Further, such model can lead to first-tier suppliers forming socially constructed identity-based coalitions for increased control (Chari, 2004; Vijayabaskar & Kalaiyarasan, 2014). Inequalities based on socially constructed identities such as race, caste, and religion persist in both developed and developing economies. Becoming tier-one suppliers requires greater resource endowments and networks, which may only be secured by dominant regional groups. So, most tier-one suppliers are likely to belong to such groups. For example, in Tirupur, a major knitwear sourcing destination in India, most tier-one suppliers are Gounders (an intermediate caste), which traditionally are farmers. When opportunities arose to participate in apparel GVCs, especially after the trade liberalization and phasing-out of the Multi-Fibre Agreement, Gounders could convert any resources they had tied up in their agricultural businesses into apparel factories. During my recent research on caste, I could not find a single Dalit (lower caste) first-tier supplier in Tirupur. Also, very few Dalits can be found in the lower tiers of the supply chain. Due to historic caste oppression and subsequent negative socio-economic consequences, they remain or become workers due to their inability to maintain their businesses (Vijayabaskar & Kalaiyarasan, 2014). This means that cascading compliance can further aggravate any historic inequalities based on socially constructed identities.

3 The origins of the dark side

The cascading compliance model leads to the perpetuation of exploitation or the reproduction of inequalities for three main reasons: coercion, exclusion, and inattention.

3.1 Coercion

Many MNEs use their power to coerce tier-one suppliers into taking on monitoring responsibilities, while not incentivizing or sharing any knowledge or resources with them (Soundararajan & Brammer, 2018). They do not support tier-one suppliers in their efforts to monitor or help lower-tier ones. Instead, they demand compliance or certifications as an ex-ante requirement for trade relationships. Without the required certifications, including those of their suppliers, tier-one suppliers cannot secure orders from MNEs. For a small share of the value they receive, tier-one suppliers struggle to balance competitiveness and the monitoring responsibilities thrust upon them. Many tier-one suppliers in the Tamil Nadu knitwear export cluster told me that price competitiveness is always the ultimate deal maker, even in the presence of all certifications. So, they must absolutely reduce their prices to stay afloat, which forces them to engage in activities that can perpetuate exploitation and reproduce inequalities.

3.2 Exclusion

Although, for its execution, the cascading compliance model relies on tier-one suppliers, they often are not consulted in regard to the development of the compliance mechanisms of the model (Schouten & Glasbergen, 2011). Their discourses and perspectives are disregarded and they are not given opportunities to share their challenges (Soundararajan et al., 2019; 2021). They are seen only as passive implementors of the mechanisms designed by MNEs and other elite actors in the developed world. None of the tier-one suppliers in the Tamil Nadu knitwear cluster have taken part in the development of the compliance mechanisms to which they are subjected. They have never been asked for suggestions or to offer feedback. Likewise, the lower-tier suppliers and their perspectives are never taken into account in the development of the compliance mechanisms. While the Partnership for Sustainable TextilesFootnote 2 and the Ethical Trading InitiativeFootnote 3 did make some efforts to bring together brands, suppliers, and other stakeholders in Tamil Nadu to develop meaningful collaborative initiatives, they failed to institutionalize due to a lack of support from MNEs. Such power plays have also been observed in relation to many other compliance certifications. For example, based on their research on the Better Cotton Initiative in India and Pakistan, Lund-Thomsen et al. (2021: 504) argued that the compliance mechanisms “can become subject to regulatory capture, serving the needs of global brands (for rapid upscaling, price minimization and verification) and sustainability standard bodies (contradictory demands for capacity building and compliance) at the expense of the intended beneficiaries — farmers at the base of global value chains.”. Suppliers thus view the compliance mechanisms as procedurally unfair and reciprocate by engaging in activities that can perpetuate exploitation and reproduce inequalities.

3.3 Inattention

Compliance certification has become the basis for supply chain relationships. MNEs make instrumental decisions in relation to their supplier selection based on compliance certifications and pay little attention to regional power dynamics, which can significantly influence GVC practices and are influenced by social structures such as race, religion, class, caste, and gender (McCarthy et al., 2021), which create a system that features an uneven distribution of resource endowments and a differential access to resources and opportunities. Those individuals who belong to dominant groups possess greater resource endowments and enjoy access to more resources and opportunities. With such power and control, the dominant groups oppress the marginalized and create hurdles to their growth. So, any focus that is limited to compliance and omits paying due attention to regional power dynamics reproduces and reinforces any regional inequalities.

4 From the cascading compliance model to a shared responsibility model

Working conditions in GVCs are a structural issue that cannot be addressed by any single actor or governance model. Multiple core and peripheral GVC actors—including MNEs, suppliers, governments, and civil societies—need to coordinate and share responsibility for the improvement of working conditions. Young (2004: 387) conceptualized labor injustices as a structural issue and put forward the philosophical idea of shared responsibility. She argued that shared responsibility is necessary “…both because the injustices that call for redress are the product of the mediated actions of many, and thus because they can only be rectified through collective action. For most such injustices, the goal is to change structural processes by reforming institutions or creating new ones that will better regulate the process to prevent harmful outcomes.”. To the end of making the shared responsibility model work, Young (2011) directed us to focus on four parameters—namely, power, privilege, interest, and collective ability. I build on her ideas to propose how diverse actors can contribute to improving working conditions in GVCs. The shared responsibility model is not about improving the cascading compliance model or about addressing its dark side. Rather, it is about identifying the root structures responsible for poor working conditions in GVCs and sharing the responsibility for affecting them.

4.1 Power

Some actors in GVCs have greater power than others to affect the structures, and thus have greater responsibility. MNEs are indeed the most powerful and resourceful players in GVCs, and do have the power to change the supply chain structure that produces poor working conditions (Alexander, 2020). For example, they could see suppliers as partners and not as discardable resources. They could also establish direct communication channels with lower-tier suppliers and workers. Building better, closer relationships with tier-one and lower-tier suppliers, as well as workers—which might include paying them better for the goods they produce, taking into account the inflation rate and cost of living of the worker’s country, and working with worker representatives and the workers themselves—could help to ensure higher standards of working conditions and higher productivity, and therefore enhanced resilience in value chains.

With respect to interventions, instead of coercive ones, MNEs could involve tier-one and lower-tier suppliers in developing interventions. They should recognize and appreciate different interests, perspectives, and discourses while developing such interventions. They should understand the challenges, pay attention to regional power dynamics and help suppliers develop the capabilities required to implement any interventions, as well as incentivize any improvements. In addition to suppliers, they could also work with workers in developing interventions (e.g., Worker-Driven Social Responsibility NetworkFootnote 4).

While MNEs do have the power to change the supply chain structure and norms, they do not have much in regard to influencing the local power dynamics and underlying social structures, which requires the type of power potentially held by governments and civil society actors. The shared responsibility model is about recognizing not just the power differentials but also the power specificities that can affect structural changes.

Beyond specific power types, the shared responsibility model also emphasizes the importance of collective power in influencing change. Although such collective power is often seen in activism-oriented activities, it can also be collaboration-oriented. For example, MNEs can collaborate with civil society actors with links to international labor rights movements in order to understand the misalignments between the expectations of MNEs and the lived experience of workers. Cross-sector partnerships have been shown to be beneficial to everyone involved (Van Tulder, Seitanidi, Crane, & Brammer, 2016).

4.2 Privilege

While power is about the ability to affect structures, privilege is about the benefits or advantages that can be gained from being a part of the GVC. So, MNCs are those who benefit more from GVCs as they get the largest share of the value. Developed world customers are also among those who benefit from products made through GVCs. Regionally, tier-one suppliers possess greater privilege as they get more value than their lower-tier counterparts. Conversely, workers, farmers, and lower-tier suppliers from vulnerable groups are the least privileged players. Thus, working conditions will be little improved by any changes that the more privileged players make to themselves; rather, such actors should recognize their privilege and the impact it has on the least privileged and should work with or enable the latter to change their practices. For example, MNEs could equitably share value with their suppliers. The margins shared by tier-one and lower-tier suppliers is one of the reasons for the perpetuation of exploitation and inequalities. Any price pressure exerted by MNEs that forces tier-one suppliers to produce at a loss is amplified on lower-tier suppliers and workers. Value sharing can result in suppliers—including lower-tier ones—being transparent with MNEs and auditors and maintaining communication to share any issues they face in ensuring better working conditions. Transparency in sharing concerns will engender trust, enable the collaborative solution of any issues as they arise, and better prepare MNEs for any problems likely to affect them in the short term (Pinnington et al., 2022).

4.3 Interest

Often, those who benefit more from the status quo have an interest in maintaining their power and privilege. On the other hand, those who benefit the least from or are exploited by the status quo challenge the system. In GVCs, workers are the most underprivileged and powerless. So, they have an interest in improving their conditions, but are unable to confront the system alone. They need the support of actors who share similar interests, such as civil society ones. Power and privilege do not mean that MNEs and suppliers cannot share the interest of workers and civil society actors. However, such powerful and privileged actors would need to question their position and recognize their contribution to the injustices in GVCs. Otherwise, they might end up engaging in activities that maintain the status quo. They could also seek the help of the underprivileged to understand them better. For example, civil society actors could help MNEs develop a better understanding of the regional power dynamics and challenges faced by workers.

At times, aggressive approaches may be required to force the powerful and the privileged to focus on the interests of the powerless and underprivileged. Consumer and civil society activism are good examples of such approaches. Policymakers could also develop laws aimed at ensuring that MNEs are not pressuring suppliers into compliance but engaging in dedicated and targeted work to the end of improving working conditions. The soft touch that characterized previous attempts to regulate GVCs (e.g., the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015) has proven inadequate against the enormously profitable abusive business models in evidence. Elsewhere in established legislation, there are precedents of severe penalties on those MNEs that fail to discharge their responsibilities. For example, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) carries provisions for any firms that fail to protect consumer data, with a maximum penalty of 10% of their global revenue. Similar penalties should be implemented to ensure that MNEs take their responsibilities in relation to improving working conditions seriously.

4.4 Collective ability

For the shared responsibility model to work, GVC actors need to develop the ability to work as a collective. There are two types of collective ability—namely, inter- and intra-group collective ability. The inter-group collective ability is about collaboration between GVCs actors belonging to diverse groups. For example, MNEs, suppliers, workers, and civil society actors need to develop the ability to work collectively in order to improve working conditions, which has shown to be beneficial to everyone involved (Van Tulder et al., 2016). The intra-group collective ability requires GVC actors to work collectively with their own group members. Worker groups, unions, and business associations are examples of groups with within-group collective ability. The problems that exacerbate poor working conditions in GVCs may be ameliorated by better collaboration between MNEs. However, MNEs fear that such collaborative efforts might breach antitrust regulations. While limitations on the ability of companies to work together are based on sound concerns, the regulators should coordinate to develop mechanisms suited to enable MNEs to cooperate to the end of improving the working conditions found in GVCs.

However, differences in power, privilege, and interests may bring about inter- and intra-group conflicts. Systems should thus be in place to resolve such conflicts and ensure that the attention of actors is steered toward the interests of the underprivileged and the powerless.

While the shared responsibility model is more promising than the cascading compliance one, it does have limitations. Like any collective action system, it does have a cooperation problem. For example, diverse actors may not share common interests, so they will not automatically come together. Then there is the free-rider problem, whereby some may try to enjoy the benefits of the shared responsibility model without actually sharing the responsibility. The fair and equitable assessment and division of responsibility may also present issues, as some may not agree with share of responsibility allocated to them. Further research is needed to identify ways to reduce the issues and make the shared responsibility model work for the betterment of everyone involved.

5 Conclusion

We have been studying and developing interventions to improve working conditions in GVCs for decades. Nevertheless, exploitation persists. This is because the interventions are not targeted at the foundational structural issues. Instead, they are only targeted at the manifestations and consequences of the structural issues. Until we address the structural causes, both supply chain and societal, the dire state of the underprivileged workers will not change. Structural changes are not straightforward. A single actor cannot fix them. Developing interventions that could target the root causes of exploitation require a coordinated effort involving privileged and underprivileged actors working together, enabling and supporting each other. The idea might sound like a fantasy, but there is enough evidence to demonstrate the power of collective action.

References

Alexander, R. (2020). Emerging roles of lead buyer governance for sustainability across global production networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(2), 269–290.

Anner, M. (2020). Squeezing workers’ rights in global supply chains: Purchasing practices in the Bangladesh garment export sector in comparative perspective. Review of International Political Economy, 27(2), 320–347.

Crane, A., Soundararajan, V., Bloomfield, M. J., Spence, L., & LeBaron, G. (2019). Decent work and economic growth in the South Indian garment industry. https://www.bath.ac.uk/publications/decent-work-and-economic-growth-in-the-south-india-garment-industry/attachments/decent-work-and-economic-growth-in-the-south-india-garment-industry.pdf

Chari, S. (2004). Fraternal capital: Peasant-workers, self-made men, and globalization in provincial India. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Fontana, E., & Egels-Zandén, N. (2019). Non sibi, sed omnibus: influence of supplier collective behaviour on corporate social responsibility in the bangladeshi apparel supply chain. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(4), 1047–1064.

Gold, S., Trautrims, A., & Trodd, Z. (2015). Modern slavery challenges to supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 20(5), 485–494.

Grimm, J. H., Hofstetter, J. S., & Sarkis, J. (2016). Exploring sub-suppliers’ compliance with corporate sustainability standards. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 1971–1984.

LeBaron, G. (2021). The role of supply chains in the global business of forced labour. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 57(2), 29–42.

Lund-Thomsen, P., Riisgaard, L., Singh, S., Ghori, S., & Coe, N. M. (2021). Global value chains and intermediaries in Multi‐stakeholder initiatives in Pakistan and India. Development and Change, 52(3), 504–532.

McCarthy, L., Soundararajan, V., & Taylor, S. (2021). The hegemony of men in global value chains: why it matters for labour governance. Human Relations, 74(12), 2051–2074.

Narula, R. (2019). Enforcing higher labor standards within developing country value chains: consequences for MNEs and informal actors in a dual economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1622–1635.

Pinnington, B., Benstead, A., & Meehan, J. (2022). Transparency in Supply Chains (TISC): Assessing and Improving the Quality of Modern Slavery Statements.Journal of Business Ethics,1–18.

Schouten, G., & Glasbergen, P. (2011). Creating legitimacy in global private governance: the case of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Ecological economics, 70(11), 1891–1899.

Soundararajan, V., Brown, J. A., & Wicks, A. C. (2019). Can multi-stakeholder initiatives improve global supply chains? Improving deliberative capacity with a stakeholder orientation. Business Ethics Quarterly, 29(3), 385–412.

Soundararajan, V., Khan, Z., & Tarba, S. Y. (2018a). Beyond brokering: Sourcing agents, boundary work and working conditions in global supply chains. Human Relations, 71(4), 481–509.

Soundararajan, V., Spence, L. J., & Rees, C. (2018b). Small business and social irresponsibility in developing countries: Working conditions and “evasion” institutional work. Business & Society, 57(7), 1301–1336.

Soundararajan, V., & Brammer, S. (2018). Developing country sub-supplier responses to social sustainability requirements of intermediaries: exploring the influence of framing on fairness perceptions and reciprocity. Journal of Operations Management, 58, 42–58.

Van Assche, A., & Narula, R. (2022). Internalization strikes back? Global value chains, and the rising costs of effective cascading compliance.Journal of Industrial and Business Economics,1–13.

Van Tulder, R., Seitanidi, M., Crane, A., & Brammer, S. (2016). Enhancing the impact of cross-sector partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(1), 1–17.

Vijayabaskar, M., & Kalaiyarasan, A. (2014). Caste as social capital: The Tiruppur story. Economic and Political Weekly, XLIX, 34–38

Villena, V. H., & Gioia, D. A. (2018). On the riskiness of lower-tier suppliers: managing sustainability in supply networks. Journal of Operations Management, 64, 65–87.

Wilhelm, M. M., Blome, C., Bhakoo, V., & Paulraj, A. (2016). Sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: understanding the double agency role of the first-tier supplier. Journal of Operations Management, 41, 42–60.

Young, I. M. (2004). Responsibility and global labor justice. Journal of Political Philosophy, 12(5), 365–488.

Young, I. M. (2011). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soundararajan, V. The dark side of the cascading compliance model in global value chains. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 50, 209–218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-022-00250-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-022-00250-0