Abstract

Strategies that make quasi-internalization feasible such as cascading compliance provide a means for lead firms to control the social and environmental conditions among their suppliers and sub-suppliers in ways other than through equity ownership. We take an internalization theory lens to reflect on the effectiveness of cascading compliance as a governance mechanism to promote sustainability along global value chains. While cascading compliance provides significant economic benefits to the lead firm, there are disincentives for suppliers to invest the required resources to meet the sustainability conditions, leading to periodic social and environmental violations. Enhanced cascading compliance (‘cascading compliance plus’) that adds trust-inducing mechanisms to engage suppliers in joint problem-solving and information-sharing has the promise to improve sustainability. But the added transaction costs that this generates has the potential to crowd-out suppliers, and possibly even make full internalization attractive again.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the last two decades, the concept of global value chains (GVC) has crept up on international business and business economics as a substitute for the ‘classic’ hierarchically structured multinational enterprise (MNE) that managed its cross-border activities as a unified entity. However, the MNE—taken to mean an organization that exercises ongoing and active coordination and control over its spatially distributed subsidiaries and affiliates, most often through full ownership of these operations—is not an endangered species. What we have seen, instead, is that there are economic and strategic rationales for MNEs to ‘loosen the apron strings’ by choosing not to internalize certain value adding activities, and instead rely on market- and quasi-market mechanisms to exert control over their GVCs.

In the context of this paper, full internalization means direct control through equity ownership, a diametrically opposed governance alternative to purely transactional arm’s length relationships such as outsourcing. While the latter may allow for lower production costs, cross-border market imperfections continue to prevail despite the reduction in transaction costs from increasing cross-border interdependence. That is, transaction costs have fallen greatly as a result of globalization, but there still remain non-negligible costs to firms from bounded reliability and opportunism of unaffiliated actors. A hierarchical setting of the classic fully internalized MNE provides a variety of coordination and enforcement mechanisms that markets do not, the primary raison d’être of the MNE in the first instance (Buckley & Casson, 1976).

The success of the GVC as an alternative mechanism to organize cross-border activities derives primarily from three things. First, the capability of MNEs to act as a meta-integrator of multiple actors within a given supply chain and coordinate these activities so as to optimise the MNE’s rent-generating potential. Second, participants in GVCs have acquired the capabilities to effectively select from a variety of alternative governance mechanisms those that minimise the net transaction costs of ongoing contracts with its immediate suppliers such that these remain lower than the fully internalised supply chain. Third, that actors within each tier of the GVC learn how to create incentives and penalties that dissuade their lower-tier suppliers from acting opportunistically, and to comply with the expectations (whether contractually or socially imposed) of its immediate customer, or those of the lead firm.

The GVC as we know it today has evolved from ‘direct contract reasoning’, with each actor taking responsibility only for its immediate (tier 1) suppliers, to whom they are contractually bound (and with whom there was active coordination and control). Social and regulatory pressures—both formal and informally—have pushed lead MNEs to accept greater responsibility for the labour practices of all the actors within their associated chain (Schrempf-Stirling & Palazzo, 2016) in what is known as a ‘full-chain approach’ (Humphrey, 2014) even where there are no direct commercial links to the lead firm. However, where there is a large network of suppliers, the associated increased transaction costs of such extensive monitoring are non-trivial. What we have seen, therefore, is a preference to implement ‘cascading compliance’, coupled with a degree of re-internalization.

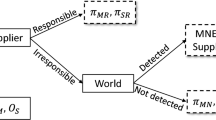

Cascading compliance presents a keen challenge to theory as its swift adoption across a variety of industries and geographical regions suggests that quasi-internalization is increasingly becoming the preferred alternative to both spot market relations and full internalization within GVCs (Asmussen et al., 2022; Narula et al., 2019). Under cascading compliance, MNEs rely on supplier codes of conduct and audit-based monitoring systems to exert control (without ownership) over the activities of their immediate first-tier suppliers, while also dictating how first-tier suppliers engage with their own suppliers (Narula, 2019). MNEs have heavily relied on this approach to promote higher environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) standards among its non-equity GVC partners, in line with the growing expectations of external stakeholders that MNEs should be held accountable for ESG abuses throughout their GVCs (Locke et al., 2009).

From a business perspective, cascading compliance has proven successful. However, from a societal perspective, the modest and uneven improvements in social and environmental conditions in many GVCs have tempered the enthusiasm about the practice (Van Assche & Brandl, 2021). There is ample evidence that even those MNEs with the best intentions struggle to ensure that compliance cascades along the GVC. For example, only recently, Uniqlo, Skechers, and Zara have been accused of exploiting forced labor in the Chinese Uyghur community. For some, these examples suggest that there is something important missing in the cascading compliance model (LeBaron, 2020), and in quasi-internalization more generally, that prevents its proper execution.

This paper considers whether the contemporaneous rise of cascading compliance and the move away from the use of traditional hierarchies through equity ownership have affected the extent to which this reduces or increases the tendency of firms within GVCs to behave opportunistically. Is cascading compliance as a governance mechanism an effective alternative to curtail corporate misconduct among suppliers? How does this compare with the ‘old school’ fully internalised multi-country MNE with wholly owned subsidiaries? Does cascading compliance require MNEs to develop a new set of transaction-based capabilities? To what extent can the MNE expect each tier of suppliers (who are boundedly reliable) to shoulder the cost burden of monitoring their own suppliers’ standard compliance? Or must the lead firm accept the higher costs of coordination and monitoring necessary to achieve effective cascading control?

Providing answers to these questions is timely, as multiple jurisdictions around the globe have started to enact binding regulations requiring MNEs to report on their supply chain’s social and environmental compliance through policy instruments such as the Dodd Frank 1502 law and the Forced Labor Prevention Act in the United States, the United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act, and France’s Duty of Vigilance law (World Economic Forum, 2022).

2 Quasi-Internalization and cascading compliance

The phenomenon of GVCs—where companies abandon the practice of producing goods or services entirely in a single country and within their own organizational boundaries—is a key international business trend that scholars have analyzed using internalization theory (Kano, 2018). Although the discussion about quasi-internalisation has its roots in understanding the growth of alliances as a preferred governance mechanism by firms for undertaking certain kinds of activity (Dunning, 1995; Narula, 2001), the discussion has matured with the growth of the GVC. Sometimes coined the “global factory” (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004), studies have conceptualized GVCs as a flexible organizational form that combines internalized and externalized governance across geographically dispersed countries to minimize the sum of production and transaction costs (Buckley, 2009; Buckley & Strange, 2015).

A key theoretical innovation that has come out of this literature is the suggestion that MNEs can take advantage of their economic power to extend their control of the GVC beyond their own legal boundaries, generating quasi-internalization or “controlling without owning” (Kano, 2018; Narula et al., 2019). The theoretical novelty of quasi-internalization is the acknowledgement that MNEs can generate control through means other than ownership, providing possibilities to achieve some of the benefits of internalization without the usual management costs of hierarchy by constraining suppliers’ behavior via relationship-based contracting that emphasizes social ties and reputation (Narula et al., 2019). Given the novelty of this research topic, many questions nonetheless remain about the effectiveness of quasi-internalization as an alternative governance mechanism within GVCs, opening up a promising new field of research.

Cascading compliance makes quasi-internalization a feasible alternative to hierarchies. It starts with the notion that MNEs have enormous economic power and thus control over the GVCs that they lead. Positioned at the top of a hierarchical chain, in principle, MNEs should have the muscle to select which suppliers are included or excluded in GVCs, to determine the terms of supply-chain membership, and to allocate where, when, and by whom value is added (Van Assche & Brandl, 2021). MNEs should also, in principle, leverage this power to impose on their network of suppliers and sub-suppliers a set of ESG standards to which they need to comply if they want to continue to be included in the GVC. In other words, MNEs can use the threat of exclusion to entice suppliers and sub-suppliers that they do not own to comply to ESG standards, generating a form of quasi-internalization.

MNEs generally rely on a combination of two control tools to promote cascading compliance: a supplier code of conduct and an audit-based monitoring system (Locke et al., 2009). A supplier code of conduct is a legal document that describes a list of ESG standards to which tier-1 suppliers need to adhere and explains the penalty for non-compliance. In most cases, MNEs require suppliers to impose those same standards on their own suppliers, thereby cascading compliance requirements down the GVC.

While there is no specific set of clauses or information that is required in a supplier code of conduct (supplier codes of conduct are voluntary), many MNEs have built their codes on Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and United Nations (UN) guidelines such as the UN Guiding Principles of Business and Human Rights, the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and the International Labor Organization’s Fundamental Principles and Rights of Work. Thus, a standard supplier code of conduct will have sections pertaining to social standards (e.g., child labor, forced labour, anti-discrimination practices, health and safety standards), environmental standards (e.g., stipulations about product and material use, the use of transportation technology, animal welfare and biodiversity) and corporate governance (e.g., anti-corruption measures and fair business practices).

As a second tool, MNEs adopt audit-based monitoring strategies to impose top-down pressures on suppliers to comply to the supplier code of conduct in their daily working routines (Locke et al., 2009). These can take on several forms. MNEs can require certificates from their suppliers and sub-suppliers, they can hire specialized private auditors to monitor the conditions in their GVCs, or they can carry out their own social audits. Walmart, for example, exclusively relies on a list of nine approved third-party audit programs to evaluate their suppliers’ compliance to responsible sourcing audit obligations.Footnote 1 Target relies on a similar list of third-party social auditors but also “maintains the right to conduct unannounced audits of any disclosed location.”Footnote 2 Nike’s Factory Ownership Compliance Program relies on “regular announced and unannounced audits conducted by internal and external parties” including the Fair Labor Association and Better Work.Footnote 3 MNEs threaten to cut those suppliers from their GVC that systematically fail compliance, providing an incentive for suppliers to comply to ESG standards.

The lackluster evidence of cascading compliance generating real improvements in social and environmental conditions among suppliers raises questions about the effectiveness of this type of quasi-internalization. Studies show that often less than fifty percent of active suppliers are socially and environmentally compliant with MNEs’ codes of conduct, as measured by audits (Goerzen et al., 2021; Villena & Gioia, 2018).

Scholars provide several perspectives on why cascading compliance fails. A first literature stream lays the onus on the MNE since it sometimes appears that they are not highly motivated to enforce cascading compliance or put into place inefficient incentive schemes (LeBaron & Lister, 2021). According to this viewpoint, MNEs may have the ability to promote sustainability through quasi-internalization but the current cascading compliance models that they use cajole with too small a carrot and threaten with too small a stick. Indeed, several scholars have blamed MNEs of heaping the costs of compliance upon the suppliers without installing effective cost-sharing or monitoring systems (Bird & Soundararajan, 2020; Locke et al., 2009). For example, recent surveys indicate that only eight percent of firms are incentivising suppliers to improve their social and environmental compliance with price premiums (Porteous et al., 2015). MNEs have also been found to avoid penalizing non-complying plants even after multiple violations (Locke et al., 2009; Porteous et al., 2015). It is sometimes alleged that MNEs proceed with such ineffective schemes since they care more about “looking good” rather than “doing good” (Lund-Thomsen, 2020).

These suboptimal outcomes appear to be exacerbated by certain highly successful business models such as “fast fashion” that emphasize speed-to-market causing peaks and valleys in demand which, in turn, encourages casual labour practices (Plank et al., 2014). In fact, Barrientos et al. (2011) document that one of the increasingly prevalent ways that developing-country suppliers in the food and apparel industries cope with short-term fluctuations in MNE demand is to engage third-party labor contractors as a channel for recruiting and to employ irregular workers (often low-skill and migrant) on an as-needed basis. These labour practices, incentivized by MNEs, often go unnoticed and can even enable bonded and forced labour at the heart of global production (Barrientos, 2013). It is well known that the use of informal employees allows firms to overcome sudden changes in demand, especially in locations where there is high unemployment. Informal workers are easier to find, cost less, and can easily be laid off where there are weak labour regulations or where the regulatory authorities are unable to enforce regulations. Lead firms are likely to ‘look the other way’ at weak internal labour standards enforcement by their suppliers if this facilitates the lead firm’s strategic and economic targets.

A second set of studies has focused on pitfalls in the audit-based monitoring system. Third-party auditors have been criticized for systematically failing to provide firms with complete and accurate information about the conditions in their GVCs (Locke, 2013), which undermine the ability of MNEs to detect, report, and resolve serious labor and environmental problems. In fact, there are several recent examples where pitfalls in social audits have been in the spotlight. For example, social audit firms repeatedly failed to report on forced labour risks at rubber glove factories in Malaysia that investigative journalism eventually exposed in 2018.Footnote 4 Following the 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, it also emerged that multiple social audit firms had failed to report on structural deficits in the building.Footnote 5 Further, in 2012, a Pakistani factory had received an SA8000 certificate just three weeks before a devastating fire broke out that killed 259 workers.Footnote 6 One critique of social audits is that it only provides a “snapshot” view of the supplier or sub-supplier’s compliance, which does not guarantee compliance on an ongoing basis and may generate evasion practices. Soundararajan et al. (2018), for example, demonstrate how knitwear garment supplies in India, both first and lower tiers, engage in various practices to produce ‘false compliance’, including training workers on what to say, terminating troublesome workers, subcontracting to uncertified units, bribing government officials and auditors. A second reason is that the quality of the social audit is strongly influenced by the relationships with the firms they monitor and by economic incentives. Short et al. (2016) conducted an analysis of nearly 17,000 supplier audits and revealed that auditors report fewer violations when individual auditors have audited the factory before, when audit teams are less experienced or less trained, when audit teams are all male, and when audits are paid for by the audited supplier.

A third set of studies suggests that the top-down compliance model is fundamentally flawed since it “almost never tackles the root causes of social and environmental problems” (LeBaron & Lister, p. 672). According to LeBaron and Lister (2021), the cascading compliance model provides significant strategic benefits for corporations, investors, and shareholders by reinforcing and legitimizing their business models and helping them position themselves as constructive citizens. But it cannot create real change in terms of social and environmental conditions since it does little to address the commercial dynamics (e.g., cost arbitrage) that help trigger the poor conditions in the first place.

For all these reasons, a growing chorus of scholars has called for MNEs to beef up their cascading compliance model with additional commitment-oriented actions that go “beyond compliance”—something which we call “cascading compliance + ” and are geared towards adding trust-inducing mechanisms that engage suppliers in joint problem solving and information sharing (Amengual et al., 2020; Anner et al., 2013; Klassen & Vereecke, 2012; Locke et al., 2009). Such interventions, which should aim to make suppliers inclusive to the compliance process, can take the form of training to improve a supplier’s ability to understand codes of conduct and implement any required corrective actions but also discussion sessions to better understand suppliers’ views and concerns. Several studies have found that capability-building interventions with heavy mentoring, information sharing, technical assistance and joint problem solving strengthened both the operations and working conditions of suppliers (Bird & Soundararajan, 2020; Distelhorst et al., 2017; Huq et al., 2014; Soundararajan et al., 2018). Of course, the idea of a ‘Cascading Compliance Plus ’ model that involves more MNE-led intervention necessarily increases costs for the lead firm, especially where one considers the case where there may literaly be hundreds of suppliers.

Taken together, a central message that comes out of the literature is that a cascading compliance model that solely relies on supplier codes of conduct and audit-based monitoring systems is rarely sufficient to ensure improvements in sustainability conditions among suppliers and sub-suppliers. To fortify the ability of MNEs to truly control without owning, there is therefore a need for them to develop additional routines and capabilities—different from those used within MNEs—that enable them to improve transparency, traceability, inclusiveness, and ultimately control throughout GVCs (Van Assche & Brandl, 2021). The investment that is needed to build the capabilities necessary to support this higher degree of quasi-internalization, however, are costly and raise the question to what point quasi-internalization remains more effective than full internalization to root out corporate misconduct in GVCs.

3 The rising costs of effective cascading compliance

At the 2022 Academy of International Business United Kingdom & Ireland Conference at the University of Reading, we organized a panel that focused on the good, bad, and ugly sides of cascading compliance and debated if growing demands for GVC sustainability would lead to renewed internalization trends. Three articles included in this special issue have come out of the panel discussion. Nieri et al. (2023) argue that a country’s degree of civil liberty critically influences an MNE’s willingness to avoid misconduct in the wake of stakeholder pressures. Wang (2023) focuses on the governance mechanisms that MNEs use to cascade compliance and explains how MNEs can leverage digital technologies to unlock the full potential of information-based governance to uphold ESG standards in GVCs. Soundararajan (2023) illustrates several ways how cascading compliance may well end up increasing labor rights violations in GVCs. Together, the authors push for more reflection on the antecedents, processes and outcomes of the cascading compliance model.

On the antecedents front, Nieri et al. (2023) make the case that the willingness of MNEs to avoid misconduct in the wake of stakeholder pressures is not only contingent on a country’s degree of regulatory pressure but also on its degree of civil liberties. According to the authors, MNEs will more likely avoid misconduct when the degree of civil liberties is high because citizens are able to both reveal corporate misconduct and organize a demand for justice. According to the authors, the role of civil liberties in fact trumps that of regulatory pressure. That is, countries with low regulatory pressure but high civil liberties will be better at avoiding MNE misconduct than countries with high regulatory pressure and low civil liberties. This is because access to technology for information and communication purposes makes it so that corporate misconduct can be exposed and punished by stakeholders even when regulatory pressures are low.

On the process front, Wang (2023) makes the argument that a distinction between the concepts of control and coordination is necessary to determine the impact of digital technology on cascading compliance. While control describes a MNE’s use of economic power to bring about supplier/subsidiary adherence to a specific goal or target, coordination portrays the less hierarchical process of achieving integration among different entities to accomplish a collective set of tasks. Digital technologies influence an MNE’s ability to control versus coordinate GVCs relations in several ways. On the one hand, digital technologies lower information-based control costs by increasing the ability of MNEs to trace and monitor the ESG conditions of its suppliers and sub-suppliers. On the other hand, it enables more flexible information-based coordination through higher interconnectivity and knowledge sharing between MNEs and their non-equity partners. Wang’s main conclusion is that MNEs should further leverage digital technologies to unlock the full potential of information-based governance to uphold ESG standards in GVCs. It is worth noting, however, that while digital technologies such as blockchain can help facilitate compliance, the implementation and utilization of blockchain has considerable costs, both in terms of hardware, as well as human capital (Chen et al., 2022). In a developing country scenario where such skills might not be commonplace, or in sectors where razor-thin margins are the norm, smaller suppliers may be unable to afford such technologies.

On the outcomes front, Soundararajan evokes several dark sides of the cascading compliance model, pointing out that it can induce unequal exclusion in GVCs if the concerns and challenges of underprivileged groups are not considered. First, cascading compliance forces MNEs to cut down non-complying suppliers and sub-suppliers, but these are often the least privileged informal entrepreneurs and workers who do not have the means to socially upgrade yet rely on GVCs for survival. Second, the increased control and coordination that cascading compliance requires may lead to MNEs and first-tier suppliers forming socially constructed identity-based coalitions, further discriminating against underprivileged groups. To counter these negative outcomes related to cascading compliance, Soundararajan calls upon MNEs to listen more to lower-tier suppliers in developing economies to counter the phenomenon of racial capitalism that directly or indirectly discriminates against the inclusion of certain underprivileged racial groups in GVCs.

4 Enhanced cascading compliance: will internalization strike back?

Our reading of the literature implies several things. First, that effective cascading compliance financially benefits the lead firm directly. Therefore, cascading compliance is likely to be most effective in the lead firm’s interaction with its immediate suppliers. Given that the lead firm tends to have a relatively small set of (large) first-tier suppliers with whom it has developed a deep interdependence over a long period, and that supply base rationalization has reduced this number in recent years, these first-tier suppliers are likely to be quite diligent in maintaining compliance, given the strategic benefits of maintaining their long-term relationship (even if it means absorbing uncompensated increased costs).

Second, compliance costs (paying for certification by third parties) has a significant fixed cost element. This means that smaller firms have a higher burden, especially where there are several different kinds of compliance requirements. We also know that some suppliers are integrated in multiple GVCs, and each GVC has its own set of standards and codes, multiplying the cost of adherence. Therefore, smaller suppliers are likely to be boundedly reliable.

Third, the further down the value chain one goes, the more likely that there will be risks of shirking in monitoring the compliance of suppliers. That is tier 2 firms will be less likely than tier 1 firms to thoroughly monitor compliance of its suppliers, and tier 3 will have even less incentives to enforce compliance on its suppliers, not simply because there is a classic principal-agent or double agency problem (Wilhelm et al., 2016), or that there are increased costs for which there is no increase in revenues to offset these costs.

Fourth, the further down the value chain one goes, the larger the number of suppliers. In the apparel industry, where work is contracted out to individuals performing piecework at home, there may literally be hundreds of suppliers. The impracticality of monitoring such a large network of suppliers, or of asking such small-scale actors to pay for multiple formal certifications, raises costs for the buyer, while also crowding out smaller actors from the sector.

Fifth, consumers and governments in many sectors increasingly expect full chain responsibility, and this has recently led to a wave of new supply chain sustainability policies in developed countries (World Economic Forum, 2022). The larger scrutiny of GVCs and the bigger penalties of non-compliance require MNEs to reassess the costs and benefits of quasi-internalization versus full integration.

The net effect of these trends would indicate that cascading compliance as it is currently practiced increases transaction costs for both suppliers and lead firms. In industries where suppliers have generic ownership advantages (and are therefore price takers), the costs are disproportionately the responsibility of the suppliers, and has the potential to crowd-out marginalized actors. A long-term solution to this dilemma is that MNEs engage in ‘enhanced cascading compliance’ (cascading compliance +), where the MNE picks up the costs of compliance and certification, or the MNE invests in building up its in-house capacity to monitor the actors in the value chain. Lead firms, can, for instance, pay for the fixed costs associated with installing digital technologies to monitor the myriad suppliers in its supply chain, or at least subsidise these actors.

The success of the GVC and the move away from full internalization has been driven largely by cost and efficiency arguments of the alternatives, on the Coasian principle that where costs were lower outside the boundaries of the firm, markets would be preferred to internalization. Quasi-internalization provides, in principle, the best of both worlds, in that MNEs maintain control without ownership, while also reducing costs. Nonetheless, what is clear is that coordination does not necessarily come without significant costs, which have risen with ESG pressures. These are the hidden costs of behaving responsibly, which have only become apparent as M|NEs have come to acknowledge that their responsibility boundaries do not align with their ownership boundaries, and while legally their failure to coordinate their supply chain compliance to standards is unenforceable, societal pressures require a realignment that does not favour their cost-minimising objective of quasi-internalization.

There is anecdotal evidence that there is some degree of reinternalization of activities by MNEs that were previously outsourced. For example, several leading chocolate companies recently decided to drop their collaboration with Fairtrade International and other certification agencies to develop their own in-house sustainability standards (Lamare et al., 2022). In addition, suppliers in certain industries have sought vertically integration, in part to achieve economies of scale and scope, but also to coordinate activities more effectively (Fung et al., 2007). It is perhaps an exaggeration to say that MNEs will return to fully integrated, hierarchical structures, as implied in the title of this paper. Perhaps it is more accurate to suggest that “quasi-internalization strikes back”, with pressures to move towards a greater degree of control and ownership to facilitate coordination, rather than “return of internalization”.Footnote 7

The compliance model’s uneven success in improving GVC sustainability and its generation of unequal exclusion forces points to the necessity for MNE’s to develop better capabilities and routines to successfully govern their GVCs through quasi-internalization. If it is too difficult for them to develop these capabilities, they may need to selectively revert to full internalization, especially in countries with low degrees of civil liberties. At the same time, digital technology is making it easier for MNEs to develop the required capabilities for information-based governance to uphold ESG standards in GVCs. Together, these findings suggest that we should expect many MNEs in the near future to take concrete actions that strengthen their ability to coordinate and control their GVCs, but likely through means other than internalization.

5 Conclusion

We have taken an internalization theory lens to reflect on the effectiveness of cascading compliance as a governance mechanism to promote sustainability along GVCs. Our analysis has shown that the current compliance model suffers of several flaws and that MNEs will need to develop stronger capabilities and routines to adequately control and coordinate their GVCs, and/or invest resources in coordination and enforcement of the entire supply chain. This points to a trend of (at least some degree of) re-internalization of GVCs in the future, or else lead firms need to engage in ‘compliance + ’ which requires a willingness of the lead firm to share some responsibility of developing the capacity of its suppliers manage the compliance of its immediate local tier. Expecting suppliers to invest in evermore ESG certification for each individual customer is expensive and creates incentives for opportunistic behaviour. It is logical to expect that firms are boundedly reliable, and will act opportunistically if they experience increased costs of compliance but no tangible compensation in revenue. Much is often made of digital technologies as a ‘simple’ solution—for instance, the use of block chain technology—but these require considerable capital outlays, often out of reach for the smaller firm, and those that have slim profit margins.

Notes

Note the double reference to Star Wars.

References

Amengual, M., Distelhorst, G., & Tobin, D. (2020). Global purchasing as labor regulation: The missing middle. ILR Review, 73(4), 817–840.

Anner, M., Bair, J., & Blasi, J. (2013). Toward joint liability in global supply chains: Addressing the root causes of labor violations in international subcontracting networks. Comparative Labour Law & Policy Journal, 35, 1.

Asmussen, C., Chi, T., & Narula, R. (2022). Quasi-internalization, recombination advantages and global value chains: Clarifying the role of ownership and control. Journal of International Business Studies, 53, 1747–1765.

Barrientos, S. W. (2013). ‘Labour chains’: Analysing the role of labour contractors in global production networks. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(8), 1058–1071.

Barrientos, S., Gereffi, G., & Rossi, A. (2011). Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. International Labour Review, 150(3–4), 319–340.

Bird, R. C., & Soundararajan, V. (2020). The role of precontractual signals in creating sustainable global supply chains. Journal of Business Ethics, 164(1), 81–94.

Buckley, P. J. (2009). The impact of the global factory on economic development. Journal of World Business, 44(2), 131–143.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. (1976). Future of the Multinational Enterprise. Springer.

Buckley, P. J., & Ghauri, P. N. (2004). Globalisation, economic geography and the strategy of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 81–98.

Buckley, P. J., & Strange, R. (2015). The governance of the global factory: Location and control of world economic activity. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(2), 237–249.

Chen, W., Botchie, D., Braganza, A., & Han, H. (2022). A transaction cost perspective on blockchain governance in global value chains. Strategic Change, 31(1), 75–87.

Distelhorst, G., Hainmueller, J., & Locke, R. M. (2017). Does lean improve labor standards? Management and social performance in the Nike supply chain. Management Science, 63(3), 707–728.

Dunning, J. H. (1995). Reappraising the eclectic paradigm in an age of alliance capitalism. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 461–491.

Fung, V. K., Fung, W. K., & Wind, Y. J. R. (2007). Competing in a flat world: building enterprises for a borderless world. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Goerzen, A., Iskander, S. P., & Hofstetter, J. (2021). The effect of institutional pressures on business-led interventions to improve social compliance among emerging market suppliers in global value chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 4(3), 347–367.

Humphrey, J. (2014). Internalisation theory, global value chain theory and sustainability standards. In International business and sustainable development (Vol. 8, pp. 91–114). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Huq, F. A., Stevenson, M., & Zorzini, M. (2014). Social sustainability in developing country suppliers: An exploratory study in the ready made garments industry of Bangladesh. International Journal of Operations & Production Management.

Kano, L. (2018). Global value chain governance: A relational perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(6), 684–705.

Klassen, R. D., & Vereecke, A. (2012). Social issues in supply chains: Capabilities link responsibility, risk (opportunity), and performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 103–115.

Lamare, M., Delgado, N. & Van Assche, A. (2022). Striving for more sustainability in the chocolate industry: the role of private governance in global value chains. Sage Business Cases. Forthcoming.

LeBaron, G., & Lister, J. (2021). The hidden costs of global supply chain solutions. Review of International Political Economy, 1–27.

LeBaron, G. (2020). Combatting modern slavery: Why labour governance is failing and what we can do about it. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Locke, R. (2013). The promise and limits of private power: Promoting labor standards in a global economy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Locke, R., Amengual, M., & Mangla, A. (2009). Virtue out of necessity? Compliance, commitment, and the improvement of labor conditions in global supply chains. Politics and Society, 37(3), 319–351.

Lund-Thomsen, P. (2020). Corporate social responsibility: A supplier-centered perspective. Environment and Planning A, 52(8), 1700–1709.

Narula, R. (2001). Choosing between internal and non-internal R&D activities: Some technological and economic factors. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 13(3), 365–387.

Narula, R. (2019). Enforcing higher labor standards within developing country value chains: Consequences for MNEs and informal actors in a dual economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1622–1635.

Narula, R., Asmussen, C. G., Chi, T., & Kundu, S. K. (2019). Applying and advancing internalization theory: The multinational enterprise in the twenty-first century. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8), 1231–1252.

Nieri, F., Rodriguez, P., & Ciravegna, L. (2023). Corporate Misconduct in GVCs: Challenges and Potential Avenues for MNEs. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics. (this issue).

Plank, L., Rossi, A., & Staritz, C. (2014). What does ‘fast fashion’mean for workers? Apparel production in Morocco and Romania. In Towards Better Work (pp. 127–147). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Porteous, A. H., Rammohan, S. V., & Lee, H. L. (2015). Carrots or sticks? Improving social and environmental compliance at suppliers through incentives and penalties. Production and Operations Management, 24(9), 1402–1413.

Schrempf-Stirling, J., & Palazzo, G. (2016). Upstream corporate social responsibility: The evolution from contract responsibility to full producer responsibility. Business and Society, 55(4), 491–527.

Short, J. L., Toffel, M. W., & Hugill, A. R. (2016). Monitoring global supply chains. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1878–1897.

Soundararajan, V. (2023). On the failure of the cascading compliance model in global value chains. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics. (this issue).

Soundararajan, V., Spence, L. J., & Rees, C. (2018). Small business and social irresponsibility in developing countries: Working conditions and “evasion” institutional work. Business and Society, 57(7), 1301–1336.

Van Assche, A., & Brandl, K. (2021). Harnessing power within global value chains for sustainable development. Transnational Corporations Journal, 28(3), 1–12.

Villena, V. H., & Gioia, D. A. (2018). On the riskiness of lower-tier suppliers: Managing sustainability in supply networks. Journal of Operations Management, 64, 65–87.

Wang, S. (2023). Unlocking information-based governance to uphold substantiality in global value chains. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics. (this issue).

Wilhelm, M. M., Blome, C., Bhakoo, V., & Paulraj, A. (2016). Sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: Understanding the double agency role of the first-tier supplier. Journal of Operations Management, 41, 42–60.

World Economic Forum. (2022). Supply Chain Sustainability Policies: State of Play, available at https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/supply-chain-sustainability-policies-state-of-play/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Assche, A., Narula, R. Internalization strikes back? Global value chains, and the rising costs of effective cascading compliance. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 50, 161–173 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-022-00237-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-022-00237-x