Abstract

A policy shift from soft law to hard law rests on assumptions about motivating compliance. The basic idea is that people comply with soft law for personal, moral reasons but are motivated to comply with hard law by self-interested fear. While logically this is obvious, there is also support for the view that self-determination, organisational justice and social influence are better at motivating compliance in certain contexts. Currently, there is a global policy shift moving corporate social responsibility (CSR) from a voluntary, organisation-based initiative to a practice mandated by law. This shift provides an opportunity to investigate the phenomenon of motivation in law. The current study investigates how the shift to mandatory CSR impacts motivation. Based on an analysis of the programs of 12 firms in Indonesia, we find that CSR hard law appears to motivate CSR without displacing voluntary moral initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Law is premised on the idea that people and the organisations they form will comply with the rules established by a recognised authority. This basic idea has dominated legal thinking since earliest times.Footnote 1 The decline of the welfare state and the rise of the regulatory state, however, has required a rethinking of this premise. Different types of regulatory instruments have been developed in response to insights into human behaviour from the social sciences. Rupp and Williams have identified ‘self-determination, organisational justice and social influence theory’Footnote 2 as significant motivators for compliance—intrinsic drivers that cause people to behave in particular ways. Further, the prohibitive costs of an increasingly cumbersome and, in many instances unworkable bureaucracy associated with inspectorates of command-and-control types of regulation, pushed government to new compliance strategies. Finally, significant, unintended consequences which arose from time to time required governments to experiment with new approaches. These new approaches have included soft law, voluntary regimes. In turn, the limitations of voluntary regimes have become clear and there is a shift back toward the mandatory rules.

The earlier challenges associated with mandatory approaches, however, have not disappeared. In fact, it has become clear that in some instances, mandatory approaches may make matters worse as people and organisations seek to evade, undermine, decouple, and oppose the rules.Footnote 3 In other instances, making behaviour mandatory drives out intrinsic motivations, further reducing compliance. The change from voluntary to mandatory CSR provides an opportunity to investigate this motivational phenomenon in greater detail.

The global dialogue on legislative action addressing corporate social responsibility (CSR) is taking notable steps from voluntary CSR toward mandatory CSR.Footnote 4 This shift is important as it effects not only corporate strategy options and corporate legal obligations, but also effects basic management issues relating to organisational programs and related behaviours at the organisational and individual levels. Organisational programs are necessary to implement CSR and to lead business organisations into more socially responsible behaviours.

It is critical to note at the outset that motivation and behaviour occur at both the organisational and personal levels. Organisations do not behave or act independently of the people managing them; rather, they act as a body in response to decisions of the leaders. These executive leaders in turn are enacting decisions derived from their own personal motivations which interact with organisational imperatives and policies. Accordingly, understanding CSR in mandatory contexts requires not only study of the regulation, but also an investigation of motivation at both organisational and individual levels. Investigating motivation and its expression is a critical part of developing our understanding of both CSR and law more generally.

Mandatory and voluntary CSR regimes aim to alter the relationship between business and society in essence making businesses more social—reducing social costs while increasing public benefits.Footnote 5 While this business and society relationship has been a live area of scholarship in corporate law and elsewhere in the academy for nearly a century, usually discussed under the rubrics of corporate purpose,Footnote 6 the shareholder/stakeholder debateFootnote 7 and stakeholder governanceFootnote 8 more broadly the current article is exclusively focused on motivation for pro-social decisions within organisations operating in a mandatory CSR environment. It does not aim to contribute to the corporate purpose scholarship beyond investigating motive in a regulated context. Its contribution to corporate law scholarship is providing insight into compliance. Understanding motivations in a more regulated context requires examination and analysis of CSR programs to evaluate them as compliance programs, strategic initiatives or expressions of existing management philosophies, or moral commitments.

Motivations are notoriously difficult to identify; however, inferences on motivation are readily made from an observation of actual behaviour of individuals, organisations and institutions.Footnote 9 In this context of mandatory CSR, senior managers have discretion to select from among a range of programs. The choices made reveals to a significant extent the underlying motivations at both organisational and individual levels. To examine and analyse these motivations, we follow the prior research on motivation in CSR, which identified three categories of motivation: ‘instrumental, relational or moral’.Footnote 10 These motivations, they note, are not singular or exclusive. Rather, it is to be expected that motivations will be mixed, particularly at the higher levels. Aguilera et al. identify regulation as a relational category; however, there is little research on mandatory CSR—a gap which is unsurprising, given the newness of mandatory CSR.

The shift to mandatory or hard law CSR has potentially significant implications for motivation and the development of CSR and insight for law reform programs.Footnote 11 While implementation and related outcomes of CSR have always been dependent upon the motivation of management at individual and organisational levels, the creation of a legal obligation of engage in CSR is a change at the institutional level creates a new motivator. Not only is this novel, it provides an opportunity to investigate the connection between these two levels of analysis and motivations for ethical behaviour.

This paper explores CSR program choices in Indonesia in response to a new regulatory environment as expressions of motivation. It focuses on the organisational level, the level of managers, through identification and examination of the programs they have selected for the investment of mandated CSR funds with some additional exploratory evidence from two case studies. This exploration and focus are used to answer the paper’s research questions:

-

RQ-1: What CSR programs were selected and developed by managers pursuant to the regulation in Indonesia?

-

RQ-2: What do these programs tell us about underlying motivation of CSR?

-

RQ-3: Are the regulations creating relationally motivated CSR programs sufficient to adequately limit instrumental motives?

-

RQ-4: Is shifting CSR to hard law an effective strategy for increasing public good and reducing harms of private enterprises?

2 Theoretical Background

Starting with CSR, over a decade ago, Aguilera et al. suggested that the pertinent question for contemporary CSR research is understanding ‘what catalyzes organizations to engage in increasingly robust CSR initiatives and consequently impart social change’ and provided an over-arching theoretical framework.Footnote 12 This proposed agenda is an invitation to investigate motivation and the proposed framework has proven its value through longevity. An underlying assumption in the literature is that ethics motivates people and organisations to engage in CSR activity.

In a related vein of legal scholarship, Sheehy has argued that CSR, as a socio-political movement, is aimed at regulating the behaviour of business organisations.Footnote 13 It is an effort to rebalance rights and duties in society, to place limits on the self-interested private behaviour deemed appropriate in the private sphere but subject to increasing limitations in the public sphere as business organisations increase in size and impact on the public.Footnote 14 For regulation to be effective, whether hard law or soft law, it must be acted upon. It must motivate actors appropriately and not lead to excessive unintended consequences nor create perverse incentives. These two overlapping lenses and literatures of CSR and law provide a theoretical framework for our article.

Finally, it should be noted that CSR programs look quite different in different geographical and economic contexts.Footnote 15 While in western and other developed country contexts, CSR is often focused on employee welfare and environmental performance, in the developing country context, CSR is often focused on the development of public infrastructure or delivery of public goods. For example, India’s CSR law requires expenditure on roads, schools and hospitals.Footnote 16 While such programs reflect the needs of the country, they also provide insight into managers’ motivation. Managers in the developing world, just as those in the developed world, must exercise discretion and make choices. They must select specific programs and we argue that such selection reflects the motivations and interests of managers.

2.1 Defining and Conceptualising Law and CSR

Regulation, a broader term for law, is developed on the assumption that parties will be motivated to comply with law’s rules. A wide variety of ideas exists on what motivates that compliance. The traditional view, associated with the 19th century legal scholar, John Austin, came from his definition of law as a command of an authority backed up by a threat.Footnote 17 Subsequent thinking has moved well beyond that basic idea to suggest that law is an institution, part of the way people think and act, a set of rules, roles and rituals which can be shaped by the exercise of formal and informal authority.Footnote 18 This more contemporary view of law and regulation underlies the view of CSR as a type of law.Footnote 19

Traditionally, CSR has been understood to be a voluntary exercise of executive discretion to allocate firm resources for projects that do not immediately or obviously benefit the firm. Instead, these allocations benefit other stakeholders.Footnote 20 More recent thinking has proposed CSR as a strategic approach to a range of competitive issues such as differentiating products, legitimacy and risk reduction.Footnote 21 In the legal sphere, CSR has been promoted as a more efficient way to achieve regulatory objectives around environmental protection and worker well-being. In legal terms, business is conceptualised on the public-private divide as a private activity and so is subjected to minimal public regulation.Footnote 22 Accordingly, CSR as an exercise of executive discretion was largely not a matter of public regulatory interest and indeed, this understanding of CSR as a ‘voluntary’ approach was incorporated into some definitions such as the European Union’s 2004 definition.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the basic binary of CSR as either voluntary or mandatory misconstrues the concept. As Mares argues, many aspects of CSR, as for example, worker safety, have long been addressed by legislation.Footnote 23 Indeed, this non-binary understanding reflects a better understanding of CSR. It can be understood as a regulatory framework, an instance of regulatory governance,Footnote 24 an emerging global soft-law system in response to corporate social costs and regulatory failures.Footnote 25 As Sheehy defines it, CSR is ‘[a] socio-political movement which generates private self-regulatory initiatives, incorporating public and private international law norms seeking to ameliorate and mitigate the social harms of and to promote public good by industrial organizations’.Footnote 26 Although CSR is generated by a combination of external social pressures and internal organisational response,Footnote 27 CSR finds itself with less space in the emerging public policy environment as an exclusively voluntary organisational act or exercise of executive decision.

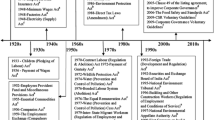

2.2 Studies of Mandatory CSR

This change in the regulatory environment is clear as the law is being reformed in different jurisdictions expressing social expectations in authoritative hard rules passed by legislatures and executive governments.Footnote 28 Governments in different regions have enacted CSR laws and regulations, as for example in Asia, (e.g., Indonesia—2007, Philippines, 2011 and Bangladesh, 2011, India, 2013, China, 2011), in Europe, (Denmark—2008, France—2010, Spain—2011, Norway—2013, European Union—2014) and in South America (e.g., Argentina and Brazil—2012). Specific national instances have significant variations. For example, India has passed programmatic CSR laws requiring business corporations to donate a certain percentage of profits to public works.Footnote 29 Similar efforts are also evidenced in the banking industry of Bangladesh where, since 2011 banking regulators issued mandatory guidelines for green banking, sustainability, and climate change funds. The Bangladeshi regulator evaluates banks’ social and environmental performance regularly.Footnote 30 The EU has mandated sustainability reporting.Footnote 31 Various common law jurisdictions have made explicit directors’ duties to consider CSR concernsFootnote 32—a position which conflicts with certain economic and management theories about stakeholders and shareholders rights.Footnote 33 Accordingly, although law has never been opposed to CSR and, indeed has required corporations to take account of non-shareholder interests—it is clear that there is increasing legislative action on the topic broadening the scope of hard rights and duties.

While prior research of mandatory CSR regulation has provided some insight into firms’ responses in jurisdictions such as the EU,Footnote 34 emerging economies such as IndiaFootnote 35 and Bangladesh,Footnote 36 there is a paucity of information about mandatory CSR in other contexts such as Indonesia. Sheehy and Damayanti’s prior study of CSR laws in Indonesia revealed high levels of corruption and unintended consequences resulting from limited case studies in national regulation.Footnote 37

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, to the best of our knowledge there has been no study of managers’ motivations and perceptions in the context of regulated CSR and only a few investigations the specific choices of post-regulatory CSR programs. Understanding the impact of regulation is a major area of study itself, and mandatory CSR is no exception. Both the positive outcomes and the unintended consequences need to be identified and addressed. To date, the only study addressing these topics is a study of managers of Indian companies where CSR legislation has been found to reduce philanthropic and other initiatives backwards from higher levels toward the regulatorily mandated baseline.Footnote 38

2.3 Motivation in CSR

Motivation is at the core of any regulatory scheme as without proper motivation, regulatory efforts are destined to fail. CSR is no exception. Motivation in CSR has been explored in a number of studies. In a foundational paper, Aguilera et al. create an analytical matrix. The vertical axis addresses motivation in terms of ‘instrumental, relational and moral’—motivators taken from Rupp & WilliamsFootnote 39 and Aguilera et al.Footnote 40 These categories of motivation can be understood as follows: instrumental motivations are those motivations which satisfy the self-interest of the actor—the ‘self-enhancing’.Footnote 41 In this usage, CSR is an instrument being used to achieve the strategic ends set by the actor. By the term ‘relational’, Aguilera et al. mean actors engaging with CSR for purposes of relationships: creating or maintaining different relationships. These relationships can range from interpersonal relationships within the firm, through market relationships to institutional relationships around the globe. By moral motivations, Aguilera et al. mean every ethical consideration from individuals’ personal meaning to national and international norms around collective responsibility and well-being—‘self-transcending’.Footnote 42 The motivations, as noted, are not understood to be mutually exclusive. Indeed, Aguilera et al. identify a hierarchy particularly at the organisational level where managers are expected to pursue in order: instrumental, relational and moral motives.Footnote 43

These three motivations, the instrumental, relational and moral of the vertical axis, operate across the whole of the horizontal axis. The horizontal axis is a range of four levels: the individual, organisational, national and supra-national. In this paper, the units of analysis are exclusively the individual and organisational level.

Because organisations operate in an institutional environment, they are inclined to respond to institutional influences, such as national law and policy, for CSR practices. Hahn and Scheermesser observe two classes of motivation for CSR activities: instrumental motives and institutional motives.Footnote 44 Instrumental motives lead companies to develop a CSR programs in the hope that these activities will enable them to improve their competitive advantage, provide new business opportunities, avoid costly regulation, reinforce corporate reputation and reduce corporate failure.Footnote 45

At the organisational level, we examine the programs implemented by organisations. These programs, while broadly stipulated by the Indonesian legislation, allow organisations to select those programs that reflect their values and interests. Thus, using Aguilera et al.’s framework, researchers can expect to see instrumental, relational and moral motives at work at the organisational level. The instrumental programs would be ones which contribute to the bottom line or enhance strategic or social standing of the organisations. Recognising the complexity of organisations, Aguilera et al. do not suggest that only one motive must be in operation. Rather, they argue that at the organisational level, all three motivations will be active, but they will be prioritised in a hierarchy that reflects the organisation’s overall objectives. Aguilera et al. propose a framework for these motives in their ‘insider downward hierarchy’, by which they mean an ordering of motives from instrumental through relational to moral.Footnote 46 We turn next to consider in greater depth the motivational categories and levels.

In terms of levels, Aguilera et al. follow Cyert and Marsh’s top management team modelFootnote 47 as comprising the organisational level. We investigate CSR programs to understand how the regulation has impacted on organisational motivations. To investigate the individual level, however, we must utilise a different framework. Thus, we look to psychological and economic studies to see how internal, intrinsic and external, extrinsic drivers motivate decision-makers.

Rupp and Williams examine the psychology motivating compliance in soft-law regimes.Footnote 48 They criticise the crude neo-classical, self- interested homo economicus to examine a range of drivers leading people to act ‘against their own self-interest and instead acting in the name of norms, cooperation, fairness, empathy and moral duty’.Footnote 49 Rather than relying on extrinsic drivers, defined in the context of regulation by Gary Becker as a ‘rational calculation of the magnitude of liability discounted by the probability of enforcement’Footnote 50 a nuanced psychological approach takes account of their other motivations. These motivations are self-determination, organisational justice and social influence theory.

Briefly, self-determination theory developed by Deci and RyanFootnote 51 suggests that humans are motivated by autonomy, a sense of competence and relatedness. These three motivators lead to a sense of motivation and responsibility. In the organisational context of CSR, these motivations would be evident where people are expressing such ideas and feelings in relation to organisational CSR programs. Organisational justice views suggest humans respond to a sense of justice at work which would be reflected in CSR programs that promote fairness in the use and applications of power.Footnote 52

Finally, in considering social influence theories, Rupp & Williams point to Kelman’s work.Footnote 53 Kelman proposed that people and organisations motivated by three processes: ‘compliance, identification, and internalization’.Footnote 54 Compliance is a form of Bentham’s desire to avoid pain and maximise pleasure. It is particularly important for the current study which examines the nature of motivation in the context of mandatory CSR. Identification refers to a desire to be identified with desirable parties and avoid shame and embarrassment of being identified with undesirable parties. Internalisation is the process of following guidelines because they reflect one’s own values and beliefs. Again, all of these theories are relevant to our consideration of the motivations operating in this mandatory context.

Examining motivation at the individual level, two studies provide significant insight. Both studies were conducted independently and examined both internal and external individual psychological motivations. The first, a study by Story and Neves investigated 229 supervisor-employee dyads to evaluate the impact of intrinsic moral motivation on employee performance.Footnote 55 In their study they found that intrinsic motivation mattered: where CSR concerns were understood to be addressed because of supervisor and executive commitment to CSR principles, employee performance was improved. This study connects with Aguilera’s individual employee focused conceptual construct. It provides some evidence of Rupp & Williams model of social influence through interpersonal relationships and organisational justice.Footnote 56

The second study surveyed of 437 executives examining their external (financial) motivation and their internal (ethical and altruistic) motivation. The Graafland study found that internal motivations were stronger across both social and environmental issues.Footnote 57 The results of this study suggest that while instrumental, strategic motivations mattered at the organisational level, executives were expressing a significant sense of Deci and Ryan’s motivation and responsibility, in the domains of relational and moral motivations.

While these findings are important, they do not provide information about motivation in other contexts. Importantly, we have limited knowledge of the impact of regulation on managerial motivation. The relationship between regulation and psychological drivers has been explored broadly by Sheehy and Feaver. In their study of the connection, they theorise that hard command-and-control law, relies on fear, while softer approaches rely on incentives—social, psychological or economic.Footnote 58

A comprehensive study of psychological motivations in soft law contexts has produced interesting insights. The previously mentioned Rupp and Williams study, investigated the utility of self-determination theory of human motivation, organisational justice theory, and social influence theory in understanding motivation in soft law.Footnote 59 They theorise a continuum at one end of which soft-law appeals to morals, while at the other end, hard law appeals to self-interest. Self-determination, they argue is manifested where Deci and Ryan’s self-determination (autonomy, competence and relatedness) are supported in environments where people feel a sense of responsibility and motivation. Organisational justice theories are those drawn upon by Aguilera et al.

Regulatory design and research have been premised on certain ideas about how people are motivated in regulatory contexts. Prior research has demonstrated an internal motivation to behave in ethical ways tends to be driven out and displaced by extrinsic reward frameworks in regulatory environmentsFootnote 60—a problem that has come to be known as ‘crowding out’.Footnote 61 Problematically for CSR, which some define as an organisational program that motivates organisations to go ‘beyond compliance’Footnote 62 Rupp and Williams point out that hard law tends to achieve no more than compliance, undermining the motivation ‘for individuals to fully meet the spirit as well as the letter of the law’.Footnote 63 As a result, mandating CSR is likely to achieve only minimal levels of desired outcomes and further, to undermine genuine efforts to contribute to public welfare. This unintended consequence of mandatory CSR at the individual level may also have a perverse outcome at an organisational level. Aguinis and Glavas observe: ‘An interesting finding regarding the effects of standards and certification is that they might actually diminish the focus on substantive CSR because management may become principally concerned with symbolic activities that serve to minimally comply with requirements.’Footnote 64

Yet, a contradictory position is derived from Rupp and Williams’ argument. They go on to note that top management may internalise justice norms, moving beyond instrumental reasons for CSR—a hypothesis that finds support in Graafland’s study—and rather than decouple, they may integrate and embed CSR more deeply into organisations. Finally, Rupp and Williams note that at times, the very act of engagement with soft norms may induce changes in thinking which may ultimately result in change in organisational culture.Footnote 65 In terms of action, however, at the organisational level, hard regulation has been a significant motivator for action particularly in environmental matters.Footnote 66 The current study, therefore, examines motivations of organisations and individual managers in the context of regulated CSR and in particular, in the context of non-Western business cultures.

2.4 CSR in Indonesia

In the specific context of Indonesia, there is a dearth of CSR research. Exceptions include Ringwati Waagstein’s (2011)Footnote 67 insightful review of its development in Indonesia including the legislation, a set of studies by Gunawan investigating stakeholder perspectives (Gunawan 2016),Footnote 68 reporting practices (Gunawan 2015)Footnote 69 the development of CSR in the hotel industry (Gunawan and Putra 2014)Footnote 70 and a critical evaluation of the development of the law mandating CSR, Article 74 of the 2007 Limited Liability Corporation.Footnote 71 Gunawan has found that CSR continues to be viewed as a cost, something to be avoided.Footnote 72 Sheehy and Damayanti’s study of the Indonesian three case studies focused on legal issues related to the structure of the positive law.Footnote 73 Their case studies provided evidence of significant corruption and unintended consequences of CSR.

Thus, while the prior studies in Indonesia provide critical evaluation of the development and implementation of law, these studies did not address management discretion and motivation in the choice of mandatory CSR programs. In this regard, our study makes an additional contextual contribution. The current study contributes to the CSR literature in the context of Indonesia by providing detail of mandatory CSR practice in Indonesia.

In the shift from voluntary soft law to mandatory hard law, we expect that the importance of self-determination, organisational justice and social influence will continue to motivate compliance with law. These intrinsic psychological drivers of human behaviour are unlikely to disappear simply because of external factors. While hard law may well work to draw attention to and focus upon specific matters of social concern, they need not be understood as necessarily driving out intrinsic motivation. Further, where the focus of the regulation is on the organisation rather than the individual, extrinsic motivation such as punishment may have a greater sounding than the finer moral aspirations of individuals.

3 The Case of Indonesian Context

Indonesia is the world’s largest island nation with a population of more than 238,000,000 people spread over 17,000 islands divided into of 34 provinces.Footnote 74 In terms of its economy, Indonesia has been forecast to be the fifth largest economy globally by 2030 and fourth by 2050.Footnote 75 Although ethnically diverse—the country consists of 300 distinct ethnic and linguistic groups—the largest and most politically dominant ethnic group is the Javanese, who comprise approximately 42 percent of the population.Footnote 76 Accordingly, we have focused our study on the island of Java and selected the province of Central Java as broadly representative of the island.

CSR in Indonesia has not arisen of its own accord. Indonesia has been a site of business focused social activism both internationally and locally orientated. Internationally, consumers have been scandalized by the behaviour of Levi’s and Nike’s suppliers in Indonesia.Footnote 77 Locally, activists have agitated for CSR while local elites have opposed such obligations, ultimately only resolved through the passing of various pieces of CSR legislation.Footnote 78

In terms of CSR in the Indonesian legal context, one is required to go back to the legal foundation, Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution. Among other things, the Constitution provides a hierarchy of laws in Article 7(1). It follows below:

-

a.

Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia of 1945;

-

b.

People's Consultative Council Decree;

-

c.

Law (or Government Regulation In Lieu of Law);

-

d.

Government Regulation;

-

e.

Presidential Decree (also known as Regulation);

-

f.

Provincial Regulation; and

-

g.

Regency/Municipality Regulation.

At the provincial level, the provinces retain considerable autonomy to make their own laws. Every province has its own Regional People’s Representatives Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah). Further, every province in Indonesia has its own Governor and regional legal bodies. Provincial laws are based on the higher laws, the Central Government’s National Laws and related regulation, and cannot be contrary to those laws. Provincial laws and regulations are made to address specific local issues and are usually in accord with Regional Development Plans. Finally, the lowest level of government, the regencies and municipalities, considerable powers still exist in terms of law creation and administration. They have power to create such rules as may be necessary to implement laws created at higher levels of government.

Indonesian law recognizes several types of business organisations from various forms of partnership including general partnerships (persekutuan perdata), limited partnerships (firma), and liability partnerships ‘CV’ (commanditaire vennootschap), through cooperatives (koperasi) to the common limited liability corporation ‘PT’ (persekutuan perdata) of Law 40/2007. Each form has its own regulations under the national law and includes making a profit as an accepted purpose. This existing legal regime prioritising profit is supplemented by the CSR regulation rather than replaced by it.

In terms of CSR regulation, after the fall of the dictator Soeharto’s New Order Regime in 1998, the new government responded to broader societal demands for corporate contributions to social issues.Footnote 79 The central government mandated CSR legislation requiring businesses, particularly those related to natural resources, to undertake CSR. In 2007, two CSR related laws were enacted: Investment Law No. 25/ 2007 and Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) Law No 40/2007, both of which laws are acknowledged as amongst the world’s first laws for mandatory CSR for state owned.Footnote 80

In addition, for listed companies, the Capital Market and Financial Institutions Supervisory Board (now the Indonesian Financial Service Authority) issued a separate a regulation, (No. X.K.6), in 2006. Under this regulation, all listed companies’ annual reports must describe activities and expenditures related to CSR to societies and environment.Footnote 81

At the provincial level, the Central Javanese government passed regulation No. 2/2017 concerning Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility, a regulation which automatically came into effect. This law was designed to implement the Republic’s Law No. 40/2007 on LLCs now superseded by 04/2020. The provincial government decided to enact its law for a variety of reasons including local companies’ lack of commitment to and practice of CSR. Prior to the regulation, companies conducted CSR as they saw fit, if at all, without any direction from government. There was no framework, no required reporting and a lack of clarity concerning both the nature and the impacts of CSR.

As noted, there were several purposes for this regulation. The first was to address the development needs of the community (Art. 3(2)). The second purpose was to increase awareness of CSR among companies of the province of Central Java. Third, was to strengthen the CSR arrangements enacted in the prior national legislation which was weak and ignored companies’ fields of expertise. Fourth, some parties had been complaining that there was a lack of clarity as to whether non-extractive Indonesian companies were obligated to comply with all national CSR rules. Accordingly, this provincial regulation provided legal certainty for companies in Central Java. And finally, the regulation provided direction to implement CSR Programs in accordance with Sustainable Regional Development Programs published by the Provincial government.

Significantly, the national law was poorly designed in that a failure to comply had no consequences. Accordingly, the Central Javanese law provided that failure to comply with the law and regulation could lead to being charged with an Administrative Sanction. In the case of this provincial regulation, the governor can order a sanction by warning letters and/or an announcement in the region’s mass media (Art. 21(2) Governor Regulation).

Finally, the law identifies the activities that will be accepted as CSR activities. Central Java Provincial Regulation No. 2/2017 on Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility, Article 13 stipulates the eleven following programs as approved CSR activities: (a) Education, (b) Well-being or health programs, (c) Sport, art or tourism programs, (d) Public welfare programs, (e) Empowering community economy programs, (f) Religious activity programs, (g) Environmental protection and management programs, (h) Agricultural or plantation or forestry or husbandry or marine and fishery programs, (I) Sustainable energy programs, (J) Emergency and mitigation programs and (K) Community assistance and infrastructure programs. While certainly these eleven stipulated activities are broad categories of activity and there is considerable room for discretion as well as self-interested activities, self-dealing and fraud, it at least provides some parameters and guidance.

These programs are all focused on relational motives. They limit, at least to some degree, the availability of overtly instrumental and moral opportunities. These latter opportunities, however, can be crafted through the application of human creativity to the task—an activity well known, for example, among business professionals as ‘creative accounting’.

Based on the foregoing discussion we have developed the following research questions:

-

RQ-1: What CSR programs were selected and developed by managers pursuant to the regulation in Indonesia?

-

RQ-2: What do these programs tell us about underlying motivation of CSR?

-

RQ-3: Are the regulations creating relationally motivated CSR programs sufficient to adequately limit instrumental motives?

-

RQ-4: Is shifting CSR to hard law an effective strategy for increasing public good and reducing harms of private enterprises?

4 Research Method

A quantitative approach was taken for this research, as this approach provides an overview of an activity as well as allows investigation into specifics of operations and internal motivation. It provides insight into the perspectives of actors through in-depth interactions and draws out their interpretations of events and programs.Footnote 82 To address our research questions we conducted a survey and documentary analysis.

In the first instance, questionnaires were sent to 50 companies, none of which were state owned enterprises, located in Central Java. There were 25 initial respondents of whom 15 completed the questionnaires in dialogue with the local researcher. The local researcher attended the offices of the companies and spoke to the responsible managers for one to two hours. During the visit, the researcher helped the managers understand the questions in the questionnaire and recorded answers. The questionnaires were in (Bahasa Indonesia) Indonesian and the discussions were conducted in a mix of Indonesian and the local language (Javanese) to facilitate a clearer understanding.

The managers were asked to provide information on a company’s CSR activities in diverse areas such as (a) Education; (b) Well-being or health programs; (c) Sport, art or tourism programs; (d) Public welfare programs, (e) Empowering community economy programs; (f) Religious activities programs; (g) Environmental protection and management programs; (h) Agricultural or plantation or forestry or husbandry or marine and fishery programs; (I) Sustainable energy programs; (J) Emergency and mitigation programs; and (K) Community assistance program and infrastructure programs. The local researcher translated the survey results and then translated respondents’ comments into English.

Secondary data was also collected from legislation, companies and local governments, and used for the development of contextual information and establishing positive law.

The researchers then categorised the eleven stipulated activities into the three motivational categories identified by Aguilera et al.: instrumental, relational and moral. As the programs are designed to both raise awareness and ensure that the primary objective of CSR, namely, community benefit is the focus, the instrumental category is blank in the first instance and contains only ‘X’ where there is a clear potential instrumental benefit to the organisation. This categorisation acknowledges Aguilera et al.’s identification of the complexity and possibility of mixed motives particularly at the organisational level. The result is set out in Table 1 below.

Certainly, these allocation of motives to regulator categorisations are not hard and indisputable. Rather, they are tentative, recognising for example, the potential for instrumental motivations to be operating in all categories while other motivations may well be operating in the other categories. For example, ensuring apprenticeships are available to local people is categorised as ‘moral’, yet, our local researcher informs that local employment is a strategy of several of the organisations to keep local stakeholders from protesting against other aspects of operations.

5 Findings

This section sets out the findings of the study. We note that a wide variety of programs were undertaken. This variety was mirrored in the responses of most of the 15 participants. We present below the tables setting out the activities. We then consider what was gleaned from the surveys pertaining to motivation.

5.1 CSR Programs Managers Selected Pursuant to the Regulation in Indonesia (RQ-1)

The overall CSR programs are given in Table 2.

From Table 2, it is clear that all the surveyed firms are engaging CSR and that a variety of programs are being implemented. Yet, it is equally clear that while there are five opportunities for instrumental programs (Regulations C, D, F, J and K), there was a concentration in C, F and K, sport, religion and community assistance and infrastructure. Programs with less instrumental appeal, education, health and empowering community (Regulations A, B and E) were still areas of investment.

Taking the analysis further, we can see that health and neighbourhood development were the most common programs. In terms of programs with greater instrumental motivations, programs related to religion, infrastructure and sport were the most common programs.

From Table 3, it is evident that firms have initiated different social programs and take into consideration of local and community needs. These initiatives include offering job opportunities to local people in surrounding neighborhoods, the establishment of health and wealth programs for the local communities and the commencement of apprenticeship programs for local high school students (8 firms).

These firms took further CSR initiatives by developing programs that integrated local and community needs and prioritized local demands and well-being (12 firms). The programs of these firms are particularly noteworthy as they align with arguments made in previous studies: CSR programs should emerge in response to local, contextual problems and issues to take account of different, distinctive settings.Footnote 83

Connecting the programs under the provincial laws with the national government mandate for CSR programs provides some interesting insights. In Table 4 below the programs are compared with nationally mandated programs.Footnote 84 All activities on Table 4, Partnership program and Community Development, arise from Republic Law 04/2020. In the table, the firms’ engagement in such programs is noted and expressed in terms of frequency and percent.

Again, it is clear from Table 4 below that there is a fair diversity of programs. There is an absence of activity in the agricultural sector for reasons unknown. The rest of the activity appears relatively evenly distributed.

Finally, we turn to consider environmental programs, programs considered to be ‘stewardship’, falling into Aguilera et al.’s moral category.

From Table 5, it is evident that firms have initiated different environmental programs to protect the natural environment. These include the establishment of environmental protection and management programs, establishment of green and tree planting programs (14 firms). Additionally, a significant number of surveyed firms took initiatives for environmental activities such as the establishment of a solid waste handling program and the development of a management program for handling environmental disasters (7 firms). Finally, 60% of firms surveyed established a liquid waste handling program (9 firms). Despite Aguilera et al. considering these programs ‘moral’ in nature, it should be noted that they are strongly implicated in economic studies as instrumental,Footnote 85 an important issue for Indonesian firms which oppose CSR in the first instance on concerns of the economic consequences.Footnote 86

It must be mentioned that many of the programs, such as religious and community infrastructure building, would have significant relationship motivations. In particular, these programs would make a strong, positive impression on local communities about the social value of the presence of these businesses in the local community. Finally, none of the programs were overtly exploited for instrumental purposes. It appears that the CSR regulation is sufficient in limiting instrumental motives. While these motives are clearly in operation as would be expected, they did not dominate to the extent of excluding the relational and moral motives.

5.2 Investigating Managers’ Opinions on CSR Issues and Their Underlying Motivation in the Regulated CSR Environment of Indonesia (RQ2 and RQ-3)

This review of programs categorised as instrumental, relational, and moral was probed in the dialogues accompanying administration of the questionnaire. In these dialogues, most firms were clear that their motivation was compliance-i.e., instrumental. They were not motivated by moral concerns for workers or neighbouring communities or the environment. Nor yet were they particularly interested in other firms’ behaviours—contrary to isomorphic theories of firm behaviour.Footnote 87 Finally, they found little interest in using CSR as a means of strategic differentiation or other economic advantage—contrary to strategic management theory on this issue.Footnote 88 Rather, CSR programs were merely one more requirement of government and simply a cost of doing business, consistent with Gunawan’s findings.

It is possible, however, to extract further information about motivation from the choice of CSR programs. It would appear that in complying with the regulation, most firms were motivated relationally, to assist the local community, as the majority of firms selected CSR programs that had a strong local focus. We note too that, with the exception of agriculture, a range of programs were chosen again reflecting consideration of the needs of the local community. Thus, beyond compliance, we can see some interest in and motivation to support the local community through different programs.

In the process of administering the survey, we found two firms that were clearly engaged in CSR programs on their own initiative pursuing moral goals. In both of these firms, the CSR programs were enactments of founders’ philosophies—philosophies about the nature of the firm and its relationship to society which provided moral motivation for the CSR programs.

5.3 Creating Relationally Motivated CSR Programs Through Regulation is Sufficient to Adequately Limit Instrumental Motives (RQ-3). Is CSR Hard Law an Effective Strategy for Increasing Public Good and Reducing Harms of Private Enterprises (RQ-4)

This study provides insight into hard CSR regulation and its operation in the context of Indonesia. It demonstrates that hard regulation is able to generate a significant response among businesses. These responses generate public good, and further, such responses are not merely limited to instrumentally motivated CSR behaviours. Rather, while certainly elements of instrumental motivation are evident in CSR programs chosen, a variety of programs, often with less obvious instrumental and more clearly relational and moral motivations of social and environmental care prevailed. Programs that made real contributions to the community were in evidence: they promoted community well-being. While certainly some, such as the religious programs, have strong, positive reputational effects, those with less obvious implications were not wholly ignored. As such, there is certain evidence of law working to limit self-interested behaviour and rebalance the private-public benefit of corporate organisations’ operations.

Further, the investment in environmental programs was unexpected. While the provincial regulation did not require it, many of the firms did (Table 5). Further, although the central government required it in some instances, as previously mentioned, there is a lack of penalty for non-compliance. The requirement of Republic Law 04/2020 (which replaced Republic Law 07/2015) is likely to have provided some incentive; however, it is unclear whether and to what extent this was the case in motivating this investment in environmental improvement.

Interestingly, there is anecdotal evidence of persistent moral motivations, setting aside instrumental motives where firm founders were motivated to be socially integrated. These moral motivations seem to persist and drive a higher quality of CSR program and engagement. Of particular note for our study, is that we did not see mandated CSR as driving out the moral motivation. While it is unclear whether moral motivations at the individual level have changed, the evidence is clear at the organisational level.

Our study demonstrates that a range of motivations continue to operate in organisations. Intrinsic, self-transcendent motivations survive and remain significant in a mandatory environment. By the same token, it is obvious that extrinsic motivations, the self-enhancing motivations are at work, as one would expect.

It is further evident that CSR can continue to be an effective flexible response to local conditions, where the regulation allows sufficient discretion to upper management. In other words, although government may have mandated CSR, the specific CSR programs may still be tailored to local community needs. The CSR programs selected by companies to a considerable degree reflected real engagement in community needs and efforts to address local community concerns. From this finding we can conclude with at least some level of certainty that there is relational motivation to meet community needs and not simply blind, lowest cost compliance. The regulation appears to be sufficient to avoid exclusively instrumentally motivated CSR and serves as a good safeguard for reducing harms from private sectors externalities. From that finding, we can say that relationally motivated CSR program limit the instrumentally motivated CSR activities in the context.

Nevertheless, it was equally clear was that for the most part, firms were engaged in CSR in order to comply with law. Most firms did little more than was required demonstrating that there was little motivation beyond compliance. In other words, there is some evidence and argument for the implementation of mandatory CSR regulation if the aim is to improve local community living. Additionally, it is clear, at least in this limited sample, that firm philosophy may remain a fundamental motivation for firms’ CSR. In particular, firms that are committed to CSR programs philosophically do not find their commitment being overridden or displaced by law. The concern that mandatory CSR will necessarily drive out philanthropic motivationsFootnote 89 as found elsewhereFootnote 90 is not borne out by the evidence in Indonesia. These findings are important because they provide counter evidence to the view that mandating CSR will do little more than drive out responsiveness and pre-existing moral motivations.

6 Conclusion

This study provides insight into motivation at individual and organisational levels in the shift from soft to hard law. Using the case of CSR regulation and its operation in the context of a developing country such as Indonesia, it demonstrates that hard regulation is able to generate a significant response among businesses for social and environmental care. The current study contributed to an understanding of law by providing insight into motivating compliance. It demonstrated that hard law can be an effective way of motivating organisations. Further, it demonstrated that hard law need not crowd out intrinsic moral motivations—and particularly, that organisational leaders will be motivated by self-determination, organisational justice and social influence in developing compliance regimes and related decision-making.

The study also provided insight into the CSR literature in two significant ways. First, the study provides critical insight on the issue of instrumental versus moral motives in the context of hard regulation. Questions about these issues were an unanswered issue in the regulation and governance and in the CSR literature. In particular, there was no study addressing the question of firm motivation, whether firms would comply with CSR regulations instrumentally or out of a moral concern for community and environmental matters in the context of the emergence of hard law. The current study contributes to the literature by answering this question. Additionally, the current study captured the attitudes of managers of CSR programs in a hard-regulatory environment. Prior studies investigated managers motivations in CSR, when CSR practises were predominantly voluntary.Footnote 91 Our study contributes to the literature by capturing managers’ CSR choices and behaviours in a hard regulatory environment.

Second, our study broadens the understanding of CSR in Indonesia. While prior research of mandatory CSR regulation provided some insight into firms’ responses in other emerging economies such as Bangladesh,Footnote 92 there was lack of information about CSR in Indonesia. The current study has contributed detailed accounts of CSR in Indonesia. This study supplements prior work on CSR in Indonesia providing insight into the implementation of lawFootnote 93 in the current case a success of sorts in comparison to the corruption found in the earlier study.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, the sample is relatively small to make strong claims of generalizability. That is an area for further study. Second, had we been able to conduct qualitative research such as using interviews, it would have been possible to probe further and add nuance to the issues of program selection and individual motivation. Third, the current study has been conducted only in the context of Indonesia, so findings cannot be generalised beyond that context. Given mandatory CSR regulations are being enacted found in other developing countries, future research can compare the effectiveness of mandatory regulation by examining two or more developing countries and taking institutional, political, and socio-economic contexts into account.

With the rapid and significant investment in the development of mandatory CSR it is clear that more research is required into regulatory design and potential unintended consequences and effects. These effects need to consider not only the actual programs developed and implemented, but also motivation, for after all, it is the underlying motivation which enlivens any compliance and informs related decision making about CSR, law and its implementation.

Data Availability

Data is available upon request.

Change history

08 August 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-023-00296-0

Notes

Sheehy (2022).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Khan et al. (2020).

Davies (2022).

Sheehy (2005).

Bebchuk and Tallarita (2020).

Hsueh (2019).

Aguilera et al. (2007).

Aureli et al. (2020).

Aguilera et al. (2007), at p 837.

Sheehy (2015).

Austin (1832).

Sheehy (2015).

Sommer (1991).

Ruder (1965).

Mares (2010).

Crouch (2009); Utting and Marques (2019), http://RMIT.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=578829.

Sheehy (2015) .

Sheehy (2017b).

Gatti et al. (2018).

Sheehy and Feaver (2014).

Sheehy (2005).

Sheehy and Damayanti (2019).

Dharmapala and Khanna (2016).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Aguilera et al. (2007).

Schaefer et al. (2020).

Ibid.

Aguilera et al. (2007).

Hahn and Scheermesser (2006).

Aguilera et al. (2007), at p 847.

Cyert and March (1963).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Ibid., at p 582—a view taken up in behavioural economics.

Cited in Rupp and Williams (2011).

Deci and Ryan (2008).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Story and Neves (2015).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Graafland and Mazereeuw-Van der Duijn Schouten (2012).

Feaver and Sheehy (2015).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Ayres and Braithwaite (1992).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Sheehy (2015).

Rupp and Williams (2011), at pp 595.

Aguinis and Glavas (2012).

Rupp and Williams (2011).

Buehler and Shetty (1974).

Waagstein (2011).

Gunawan (2016).

Gunawan (2015).

Gunawan and Putra (2014).

Sheehy and Damayanti (2019).

Gunawan (2016).

Sheehy and Damayanti (2019).

Pusponegoro and Notosusanto (2008).

PWC, The World in 2050: Will the Shift in Global Economic Power Continue. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/the-economy/assets/world-in-2050-february-2015.pdf.

Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Indonesia [Indonesian Bureau of Statistics], Sensus 2010. https://sp2010.bps.go.id/.

Sharma (2013).

Sheehy and Damayanti (2019).

Kemp (2001).

Waagstein (2011).

Yin (2009).

Sheehy and Damayanti (2019).

Reinhardt et al. (2008).

Gunawan (2016).

DiMaggio and Powell (1983).

Heslin and Ochoa (2008).

Ayres and Braithwaite (1992).

Bhagawan and Mukhopadhyay (2019).

Sheehy and Damayanti (2019).

References

Aguilera RV, Rupp DE, Williams CA, Ganapathi J (2007) Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: a multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 32(3):836–863

Aguinis H, Glavas A (2012) What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: a review and research agenda. J Manag 38(4):932–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079

Aureli S, Del Baldo M, Lombardi R, Nappo F (2020) Nonfinancial reporting regulation and challenges in sustainability disclosure and corporate governance practices. Bus Strat Environ 29(6):2392–2403. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2509

Austin J (1832) The province of jurisprudence determined, 1995 edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ayres I, Braithwaite J (1992) Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press, New York

Baldwin R, Cave M (1999) Understanding regulation: theory, strategy, and practice. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bebchuk LA, Tallarita R (2020) The illusory promise of stakeholder governance. Cornell L Rev 0106:91

Belal AR, Owen DL (2007) The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh: an engagement-based study. Account Audit Account J 20(3):472–494

Bhagawan MP, Mukhopadhyay JP (2019) Does mandatory expenditure on CSR affect firm value? Empirical evidence from Indian firms. Paper presented at the Financial Markets & Corporate Governance Conference, 2019

Black J (2005) Regulatory innovation: a comparative analysis. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Bose S, Khan HZ, Rashid A, Islam S (2018) What drives environmental disclosure? An institutional and corporate governance perspective. Asia Pacific J Managt 35(2):501–527

Braithwaite J (2002) Rewards and regulation. J Law Soc 29:12–26

Buehler VM, Shetty Y (1974) Motivations for corporate social action. Acad Manag J 17(4):767–771

Campbell JL (2007) Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad Manag Rev 32(3):946–967. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.25275684

Caputo F, Pizzi S, Ligorio L, Leopizzi R (2021) Enhancing environmental information transparency through corporate social responsibility reporting regulation. Bus Strategy Environ 30(8):3470–3484. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2814

Carroll AB (2015) The state of CSR in 2015 and beyond. Global compact international yearbook. Macondo Publishers, New York, pp 10–13

Carroll AB, Shabana KM (2010) The business case for corporate social responsibility: a review of concepts, research and practice. Int J Manag Rev 12(1):85–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00275.x

Cominetti M, Seele P (2016) Hard soft law or soft hard law? A content analysis of CSR guidelines typologized along hybrid legal status. UmweltWirtschafts Forum 24(2):127–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00550-016-0425-4

Costa E, Agostini M (2016) Mandatory disclosure about environmental and employee matters in the reports of Italian-listed corporate groups. Soc Environ Account J 36(1):10–33

Crouch C (2009) CSR and changing modes of governance: towards corporate noblesse oblige? In: Utting P, Marques JC (eds) Corporate social responsibility and regulatory governance: towards inclusive development? Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 26–49

Cyert RM, March JG (1963) A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall/Pearson Education. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Davies PL (2022) Shareholder voice and corporate purpose: the purposeless of mandatory corporate purpose statements. Available at SSRN European Corporate Governance Institute - Law Working Paper No. 666/2022, pp 1–46

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2008) Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol 49(3):182–185

De Mendonca T, Zhou Y (2020) When companies improve the sustainability of the natural environment: a study of large U.S. companies. Bus Strat Environ 29(3):801–811. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2398

Dharmapala D, Khanna VS (2016) The impact of mandated corporate social responsibility: evidence from India’s Companies Act of 2013. Int Rev Law Econ 56:92–104

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW (1983) The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am Sociol Rev 48(2):147–160

Feaver D, Sheehy B (2015) A positive theory of effective regulation. UNSW Law J 35(3):961–994

Gatti L, Vishwanath B, Seele P, Cottier B (2018) Are we moving beyond voluntary CSR? Exploring theoretical and managerial implications of mandatory CSR resulting from the new Indian Companies Act. J Bus Ethics 160:961–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3783-8

Graafland J, der Duijn M-V, Schouten C (2012) Motives for corporate social responsibility. De Economist 160(4):377–396

Gunawan J (2015) Corporate social disclosures in Indonesia: stakeholders’ influence and motivation. Soc Responsib J 11(3):535–552

Gunawan J (2016) Corporate social responsibility initiatives in a regulated and emerging country: an Indonesia perspective. In: Idowu S (eds) Key initiatives in corporate social responsibility. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance.: Springer, Switzerland, pp 325–340

Gunawan J, Putra ZDP (2014) Demographic factors, corporate social responsibility, employee engagement and corporate reputation: a perspective from hotel industries in Indonesia. Chin Bus Rev 13(8):509–520

Hahn T, Scheermesser M (2006) Approaches to corporate sustainability among German companies. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 13(3):150–165

Heslin PA, Ochoa JD (2008) Understanding and developing strategic corporate social responsibility. Organ Dyn 37:125–144

Hsueh L (2019) Opening up the firm: what explains participation and effort in voluntary carbon disclosure by global businesses? An analysis of internal firm factors and dynamics. Bus Strat Environ 28(7):1302–1322. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2317

Jamali D, Karam C (2018) Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. Int J Manag Rev 20(1):32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12112

Jamali D, Mirshak R (2007) Corporate social responsibility (CSR): theory and practice in a developing country context. J Bus Ethics 72:243–262

Kelman HC (2006) Interests, relationships, identities: three central issues for individuals and groups in negotiating their social environment. Ann Rev Psychol 57:1–26

Kemp M (2001) Corporate social responsibility in Indonesia: quixotic dream or confident expectation? Technology, business and society programme paper number 6, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development

Khan HUZ (2010) The effect of corporate governance elements on corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: empirical evidence from private commercial banks of Bangladesh. Int J Law Manag 52(2):82–109

Khan HZ, Halabi AK, Samy M (2009) Corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: a study of selected banking companies in Bangladesh. Soc Responsib J 5(3):344–357

Khan HUZ, Mohobbot AM, Fatima JK (2014) Determinants and recent development of sustainability reporting of banks in developing countries: the case of Bangladesh. Corp Ownership Control 11(4):505–520

Khan HZ, Bose S, Johns R (2020) Regulatory influences on CSR practices within banks in an emerging economy: do banks merely comply? Crit Perspect Account 71:1–20

Khan HZ, Bose S, Sheehy B, Quazi A (2021a) Green banking disclosure, firm value and the moderating role of a contextual factor: evidence from a distinctive regulatory setting. Bus Strateg Environ 30(8):3651–3670

Khan HZ, Bose S, Mollik AT, Harun H (2021b) ‘Green washing’ or ‘authentic effort’? An empirical investigation of the quality of sustainability reporting by banks. Account Audit Accountab J 34:338–369

Kinderman D (2018) The challenges of upward regulatory harmonization: the case of sustainability reporting in the European Union. Regul Gov 14(4):674–697

Kochhar SK (2014) Putting community first: mainstreaming CSR for community-building in India and China. Asian J Commun 24(5):421–440

Kourula A, Moon J, Salles-Djelic M-L, Wickert C (2019) New roles of government in the governance of business conduct: implications for management and organizational research. Organ Stud 40(8):1101–1123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619852142

Mares R (2010) Global corporate social responsibility, human rights and law: an interactive regulatory perspective on the voluntary-mandatory dichotomy. Transnatl Leg Theory 1(2):221–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/20414005.2010.11424508

Mukherjee K (2017) Mandated corporate social responsibility (mCSR): implications in context of legislation. In: Raghunath S, Rose E (eds) International business strategy. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54468-1_19

Pedersen ERG, Neergaard P, Pedersen JT, Gwozdz W (2013) Conformance and deviance: company responses to institutional pressures for corporate social responsibility reporting. Bus Strat Environ 22(6):357–373

Pusponegoro MD, Notosusanto N, 1930-1985 (2008) Sejarah nasional Indonesia / editor umum, Marwati Djoened Poesponegoro, Nugroho Notosusanto. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka

Reinhardt FL, Stavins RN, Vietor RHK (2008) Corporate social responsibility through an economic lens. Rev Environ Econ Policy 2(2):219–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/ren008

Rosser A, Edwin D (2010) The politics of corporate social responsibility in Indonesia. The Pacific Rev 23(1):1–22

Ruder DS (1965) Public obligations of private corporations. Univ Pennsyl Law Rev 114(2):209–229

Rupp DE, Williams CA (2011) The efficacy of regulation as a function of psychological fit: re-examining the hard law/soft law continuum. Theor Inq Law 12(2):581–602

Schaefer A, Williams S, Blundel R (2020) Individual values and SME environmental engagement. Bus Soc 59(4):642–675

Sen S, Bhattacharya CB (2001) Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J Market Res 38(2):225–243

Sharma B (2013) Contextualising CSR in Asia: corporate social responsibility in Asian economies and the drivers that influence its practice. Singapore, Lien Centre for Social Innovation: 1–295

Sheehy B (2004) Corporations and social costs: the Wal-Mart case study. J Law Commer 24:1–55

Sheehy B (2005) Scrooge – the reluctant stakeholder: theoretical problems in the shareholder-stakeholder debate. Univ Miami Bus Law Rev 14(1):193–241

Sheehy B (2012) Understanding CSR: an empirical study of private self-regulation. Monash Univ Law Rev 38(2):103–127

Sheehy B (2015) Defining CSR: problems and solutions. J Bus Ethics 131(3):625–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2281-x

Sheehy B (2017a) Conceptual and institutional interfaces among CSR, corporate law and the problem of social costs. Va Law Bus J 12(1):95–145. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156751

Sheehy B (2017b) Private and public corporate regulatory systems: does CSR provide a systemic alternative to public law? UC Davis Bus Law J 17:1–55. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2157316

Sheehy B (2020a) Corporate social responsibility and sustainability reporting: transitioning from transnational soft law to domestic hard law (26 November 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3738373

Sheehy B (2020b) Emerging corporate social responsibility rights and duties: law experiments in Spain, India, Indonesia and soft law (2 December 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3740949

Sheehy B (2022) Paradigms of legal scholarship: connecting theories, methods and problems in doctrinal, realist and non-law focused research (22 December 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4309144

Sheehy B, Damayanti C (2019) Issues and initiatives: sustainability and CSR in Indonesia. In: Sjåfjell B, Bruner CM (eds) Cambridge handbook of corporate law, corporate governance and sustainability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 475–489

Sheehy B, Feaver DP (2014) Anglo-American directors’ legal duties and CSR: prohibited, permitted or prescribed? Dalhousie Law J 37(1):347–395. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2157315

Sheehy B, Feaver D (2015) A normative theory of effective regulation. UNSW Law J 35(1):392–425

Sommer AAJ (1991) Whom should the corporation serve—the Berle-Dodd debate revisited sixty years later. Del J Corp Law 16:3–56

Story J, Neves P (2015) When corporate social responsibility (CSR) increases performance: exploring the role of intrinsic and extrinsic CSR attribution. Bus Ethics: Eur Rev 24(2):111–124

Subramaniam N, Kansal M, Babu S (2017) Governance of mandated corporate social responsibility: evidence from Indian government-owned firms. J Bus Ethics 143(3):543–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2804-0

Teubner G (1984) Corporate fiduciary duties and their beneficiaries: a functional approach to the legal institutionalization of corporate responsibility. In: Hopt K, Teubner G (eds) Corporate governance and directors' liabilities: legal, economic and sociological analysis on corporate social responsibility. De Gruyter, Berlin & New York, pp 149–177

Turkina N, Neville B, Bice S (2015) Rediscovering divergence in developing countries' CSR. In: Jamali D, Karam C, Blowfield M (eds) Development-oriented corporate social responsibility: locally led initiatives in developing economies (vol 1). Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing, pp 13–36

Utting P, Marques JC (2019) Corporate social responsibility and regulatory governance: towards inclusive development? http://RMIT.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=578829

Waagstein PR (2011) The mandatory corporate social responsibility in Indonesia: problems and implications. J Bus Ethics 98(3):455–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0587-x

Yin J, Zhang Y (2012) Institutional dynamics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in an emerging country context: evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 111(2):301–316

Yin R (2009) Case study research: design and methods. 3rd edn, vol 5. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dean Prof. Dr. Retno Saraswati of Diponegoro University, Indonesia for her support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. There was no funding for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by BS, HZK, PP and PS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Benedict Sheehy and all authors commented.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

Human research ethics were addressed via the protocols of the relevant body, Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheehy, B., Khan, H.Z., Prananingtyas, P. et al. Shifting from Soft to Hard Law: Motivating Compliance When Enacting Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 24, 693–719 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-023-00284-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-023-00284-4