Abstract

We survey institutional investors to understand why they integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into their investment management processes. Using a unique data set, we find that limited partners (LPs) are motivated to incorporate ESG because they believe that ESG usage is more strongly correlated with financial performance. We find that general partners (GPs) are motivated to integrate ESG factors into their investment strategies in response to increased client demand for sustainable products. Furthermore, we find that private equity (PE) uses ESG factors more intensely than venture capital (VC) regardless of geography. We also find that PE firms use voice and exit strategies more extensively than VC funds in efforts to promote ESG activities in companies. When evaluating individual components of ESG scores, we find that the investors consider the governance score the most important component, followed by E, and then S.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The last decade has seen a rapid increase in the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into the investment decisions of institutional investors. Data from Natixis Investment Managers indicate that the percentage of institutional investors that choose to integrate ESG factors into investment decisions increased by 18% between 2019 and 2021.Footnote 1 Despite the strong growth in ESG integration across investor types, however, many institutional investors still choose to integrate just one or two of the factors or have yet to consider ESG factors at all in their asset allocation process.Footnote 2 Moreover, while articles in this literature have focused on the ESG fund segment generally,Footnote 3 relatively little is known about ESG integration in private markets. And while much literature considers the implications of climate risk for investors,Footnote 4 comparisons between E, S and G considerations for investors remain under-explored.Footnote 5 There are relatively few empirical studies examining ESG considerations for limited partners (LPs) and general partners (GPs).

There is a large literature on the effect of ESG integration into investment strategies.Footnote 6 We are motivated by three stands of the literature that reach different hypotheses on the integration of ESG factors. The first strand argues that that most institutional investors take ESG factors into account because they believe them to be linked to financial performance.Footnote 7 The second strand argues that the link between ESG and firms’ financial performance is the combined effect of a sufficiently large number of investors acting on non-financial motives to slant their portfolios towards firms with strong ESG criteria and away from firms with poorer ESG quality. In these models, the subset of investors acting this way needs to be just large enough to raise the cost of capital for firms with poor ESG quality in order to provide a financial incentive to invest in improving ESG quality and, thus, to attract a larger number of investors.Footnote 8 The third stand argues that the positive relationship between ESG and financial performance involves considering the risk benefits that may accrue to individual firms due to their ESG characteristics, as well as the diversification benefits related to firms’ ESG characteristics.Footnote 9 In these studies, the improved financial performance depends on how the portfolio manager uses ESG screenings.Footnote 10

In order to shed light on these questions, we study the effect of institutional investors’ perceived importance of ESG factors for their investments in private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC), as well as the factors that influence alternative asset managers to incorporate ESG factors into their portfolio allocations. In order to empirically study these questions, we introduced a new dataset from a 2020 survey of institutional investors. The survey data comprise information from 106 UK, European and North American institutions, as well as from a small percentage of respondents around the world who are currently investing in private equity and venture capital. In the survey, we asked investors about their motivations for considering ESG factors, the relative importance of ESG criteria, their use in relation to risk and return considerations, how often ESG criteria are considered and in which stages of the portfolio management process, and for what screening or evaluative purposes ESG criteria are employed.

To assess the barriers to and motives for ESG integration, we first present basic statistics showing the reasons that these investors consider integrating ESG into their investment process. We find that, on average, 48% of institutional investors rate investment riskiness as their first or second important reason for considering ESG, compared to only 13% for diversification purposes. Meanwhile, 45% respond that they rate an ESG mandate as first or second. This is consistent with evidence that institutional investors increase inflow of funds by signing onto the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) even if they underperform financially.Footnote 11 We also evaluate investor views on the barriers to ESG usage in the investment asset management process. The results here indicate that the absence of accurate data and the weak comparability of data are the most important hurdles to the implementation of ESG criteria.

We asked LPs and GPs to rate the motivations that would influence them to adopt ESG factors in their investment decision processes. Although GPs recognize the correlations with financial performance, they are more motivated to respond to clients’ demands (i.e., demand from LPs). Not surprisingly, we find that LPs are more motivated by the belief that there are correlations with investment risk generally.

We distinguish between PE and VC investment funds in order to proxy for the average age of portfolio companies and the added risk and uncertainty that accompanies investments in earlier-stage companies. We find that PE firms use ESG factors more intensely than do VC funds regardless of geography. Moreover, we find that PE firms use voice and exit strategies more extensively than VC funds in an effort to promote ESG activities in companies. Considering that VC funds are generally investing in early-stage and newer companies while PEs are engaged in enhancing value in more established companies, our results are consistent with findings that investors with longer-term horizons engage more with the ESG quality of companies in their portfolios.Footnote 12

Next, we study the complementary use of voice and exit strategies by PE and VC firms to manage their ESG issues with companies. We document that GPs use exit and voice more often than LPs. While our interview evidence confirms that LPs will address ESG concerns about a particular company with a GP, this is only for egregious concerns. Our findings highlight, among other things, that LPs do not have the same significant effect on governance that GPs have.

We also study investors’ views on the relative importance of the E, S and G scores individually. It is well known that institutional investors are increasingly implementing ESG scores into their portfolio management activities.Footnote 13 Surprisingly, this relation has not been explored in the literature until recently. We find that investors, when evaluating individual components of ESG scores, consider the governance score the most important component, followed by E, and then S. Our findings generally support the theoretical argument that ESG, particularly the governance dimension, is related to decreased risk.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature. Section 3 describes the methodology. Section 4 examines the summary statistics. Section 5 presents the results. Section 6 concludes.

2 Motivation and Literature Review

This section provides an overview of the existing theoretical and empirical literature, as well as the motivation for this research and the hypothesis development.

The ESG preferences of investors depend very much on the style and strategy of investors when integrating ESG. Strategies can vary from avoiding ‘sin stocks’Footnote 14 to more active ways of involving ESG risk management into the investment decision process. They can also encompass a focus on broader measures of corporate social responsibility (CSR) or be more actively pursued strategies of sustainability (sustainable equity, credits, multi-asset or infrastructure debt) and/or impact (green bonds, impact equity, emerging market loans).Footnote 15 The studies to date have not differentiated their findings with regard to the strategy that investors deploy. There is also not a common definition of what the different strategies entail exactly. That is, at least in part, the evidence explaining the impact of ESG factors—for example, on financial performance—is mixed at best. Thus, we try to differentiate among the effects of the different styles, but also consider other aspects of ESG relevant to investors and firms; we then turn to the literature on ESG data and disclosure and finally explore the literature concerning investors’ voting and other engagement strategies concerning ESG, which are relevant after the investment decision has been made.

A large literature on ESG investing has emerged in recent years. Two meta studies provide a useful overview of this literature up until 2015. Both studies find a remarkable correlation between ESG and economic performance. One studyFootnote 16 explores the business case for ESGFootnote 17 by looking into the relationship between ESG and cost of capital and operational performance, as well as stock price effects of ESG, and the results of active ownership. The study reviews and categorizes more than 200 academic papers, industry reports, newspaper articles and books and concludes that 90% of the studies on the cost of capital show that sound ESG standards lower companies’ cost of capital. Further, 88% of the research shows that solid ESG practices result in firms’ better operational performance, and, finally, 80% of the studies show that companies’ stock price performance is positively influenced by good ESG practices.Footnote 18

The other meta study focuses exclusively on the effect of ESG on financial performance but captures even more academic resources.Footnote 19 It extracts all of the primary and secondary data from previous academic studies, thereby combining the findings of 2200 individual studies. This research shows that roughly 90% of the studies find a non-negative relation between ESG and corporate financial performance. The effect of ESG on financial performance is still the core question,Footnote 20 often presented in terms of whether a trade-off exists for investors between the financial and non-financial dimensions of the investment.

2.1 ESG and Its Impact on Investment Performance

In the following, we aim to distinguish between active and passive strategies of integrating ESG to see what impact they may have on firms’ financial performance, as well as on investors’ performance. This distinction is more commonly accepted: passive strategies focus on negative screening of certain industries, whereas active strategies are all other strategies that include some form of positive screening of ESG. Differentiating among those active strategies is more difficult. Below we make a distinction between strategies that focus on ESG as an element of investment risk analysis versus those whereby the investor decides to focus more on an ESG-related opportunity or market segment, as with so-called sustainability or impact strategies (e.g., alternative energy as the main focus of a fund would fall under this category.)

Originally, the effects of ESG were examined only for negative screening strategies, commonly referred to as ‘avoiding sin stocks’. Examples for such studies are manifold.Footnote 21 This type of negative screening, however, is now considered the most detrimental to financial performance and, nowadays, full integration of ESG into stock valuation, active ownership, and positive screening is considered much more beneficial.Footnote 22

In this regard, a strand of literature examines financial performance of sustainable investment portfolios and generally fails to find any performance differences between SRI funds and conventional mutual funds,Footnote 23 which can be due to difference in investment styles.Footnote 24 It is questionable whether an investment in an SRI fund reflects a stable ESG profile over time and, indeed, offers higher exposure to ESG values than conventional funds do.Footnote 25

2.2 Financial Performance with Active ESG Strategies—Tackling Investment Risk

The more active consideration of ESG factors often starts with the understanding that such factors can be negatively related to extreme downside risk. Shafer and Szado have shown that better ESG practices, as well as better practices in the individual E, S and G pillar, significantly reduce ex ante expectations of a left-tail event.Footnote 26 Hamilton shows a significant negative impact of the announcements of the release of information about the use of toxic chemicals on stock prices in the US,Footnote 27 with similar effects being observed for other countries in Latin America and Asia.Footnote 28 In a similar vein, Hoepner et al. highlight that ESG issues can benefit shareholders by reducing firms’ downside risk.Footnote 29

There is general agreement among investorsFootnote 30 that successful ESG investing depends on integrating ESG factors with the methods and data of traditional ‘fundamental’ financial statement analysis. ESG concerns tend to show up as risk factors that can translate into higher costs of capital and lower values. Many fundamental investors view companies’ effectiveness in managing such factors as an indicator of management ‘quality’. Fixed‐income investors are equally concerned as equity investors about ESG exposures, eventually generating ‘tail risks’ that can materialize in both going‐concern and default scenarios.Footnote 31 According to the view above, ESG integration is not different from any other analysis, it is simply a matter of integrating all relevant information.Footnote 32 Others, however, argue that ESG information presents itself as an extra level of intelligence that can also provide insight into future performance next to fundamental information, which relies heavily on a company’s financial statements and technical information, and can be derived from a company’s past performance in the stock market.Footnote 33

Building on the growing investment practice of considering ESG as risk factors in financial analysis, ESG can also be used to diversify risks in portfolio construction. Sherwood and Pollard show that integrating ESG emerging market equities into institutional portfolios could provide institutional investors the opportunity for higher returns and lower downside risk than non-ESG equity investments.Footnote 34 This link has been also acknowledged in key studies such as the UN Principles of Responsible Investment’s (PRI) ESG and alpha study, which found that, in the US, ESG information offers an alpha advantage in equities portfolios across all regions.Footnote 35

2.3 Financial Performance Under Sustainability and Impact Strategies

In contrast to the literature on ESG risk management, studies on the impact of ESG on financial performance with opportunity-driven sustainability and impact strategies are scant. With such strategies, ESG not only is considered as a risk factor, but also plays a role in the active selection or screening of investment opportunities. Strategies focusing on the UN Sustainable Development Goals represent a new trend in this area.Footnote 36

A large part of the existing literature that considers the ESG impact of these even more active strategies reviews the performance of green bonds,Footnote 37 which are only one aspect of an impact-related strategy. Most empirical studies report that the investment returns of green bonds are not superior.Footnote 38 Martin and Moser conducted an experiment in which they found that managers’ green investments have no impact on future cash flows in their experimental markets, but that investors respond favorably when managers make and disclose an investment and highlight the societal benefits rather than the cost to the company.Footnote 39 Moreover, Renneboog et al.’s results suggest that a subset of investors is willing to accept lower financial performance to invest in funds that meet social objectives.Footnote 40

Beyond the impact of ESG on financial performance and the unclear results of impact- and sustainability-related strategies, investors may have other motivations to consider ESG (more thoroughly), which we now explore.

2.4 Other Motivations for ESG Consideration by Investors

Investors, in general, may be motivated for three reasons: performance motives (investment performance); financial motives (product strategy or client demand); or ethical considerations.Footnote 41 Originally, the last element was the core motivation and defined an investment stride independent of ESG, usually referred to as ethical investing. Over the last five to ten years, financial performance seemed to be the main driver, but as we have shown, results—except for the category of considering ESG as an investment risk—are mixed. Even with such results, client demand will become more important over time and will convince even more investment managers.Footnote 42 Such demand may also be further reinforced by regulatory measures.Footnote 43

2.5 Firm Returns from ESG Investments

What has been shown as investors’ main motivation is also relevant for firms and their quest to integrate ESG into their managerial practices. Firms can be motivated by financial performance but also by the demand of investors, which in the case of firms would ultimately translate into lower costs of capital. With regard to the first aspect, financial performance, there are a number of studies that look at the environmental management of the firm and associated higher returns,Footnote 44 as well as at the cost-benefit of higher environmental standards.Footnote 45 Most of these studies come to the conclusion that enhanced environmental practices or standards lead to higher financial performance.Footnote 46 Brummer offers a more critical view with regard to a company’s social performance and its impact on the financial performance of the firm.Footnote 47 Regarding corporate governance, most of the available literature examines (in most studies positive) the correlation between firm-level corporate governance practices and different measures of firm performance.Footnote 48

Aside from the direct benefit of investing in ESG, firms can also be motivated by the preferences of investors rather than by the actual positive effect of ESG on their bottom line. If enough investors trigger a firm to present itself as not only profit-driven, that firm gains a competitive advantage in attracting investors, which in turn will lower its cost of capital. The existing literature often explains ESG investments as being driven by a subset of investors that have a non-financial component of utility.Footnote 49 In order to provide firms with a positive incentive to invest in ESG, this subset of investors needs to be just large enough to raise the cost of capital for firms that do not invest in ESG.Footnote 50 Likewise, negative ratings may also ultimately influence firms to do more. It has been shown that firms that initially receive poor environmental ratings, improve their environmental performance more than other firms.Footnote 51 Finally, McWilliams and Siegel show how companies can offer the ideal level of ESG measures that maximizes profit, while at the same time satisfying stakeholder demand for ESG.Footnote 52

2.6 ESG Data and Disclosure

As we have shown above, most of the literature finds it rewarding for firms to implement sustainable management strategies either because such strategies do, indeed, improve some measure of financial performance or because they lower the costs of capital due to strong investor demand for enhanced ESG practices. To successfully implement such strategies, companies are required first to identify the specific sustainability issues that are material to them. Unfortunately, the materiality of ESG issues differs substantially among industries. Mining has a different exposure to ESG than real estate has, for example.Footnote 53 The materiality of the different ESG issues likely varies systematically across firms and industries.Footnote 54 Firms nowadays release a wealth of information in the form of ESG data, but the number of ESG- related issues that attract investment raises the question of which of these ESG data are more or less material.Footnote 55

Given the above, it is not surprising that the literature has identified several issues around ESG data. Such work implies that the ESG data universe is getting too complex and confusing. Several studies show that there is very little agreement among rating agencies and data vendors on how to construct and use ESG measures.Footnote 56 Similarly, such differences were shown earlier, exclusively for governance-related dataFootnote 57 and environmental data.Footnote 58 In more recent work, Gibson et al. provide evidence on the impact of ESG rating disagreement on stock returns.Footnote 59

Starting with Eccles and Stroehle, a number of papers have explored the root causes for data differences by looking at the different dimensions used for the definitions of sustainability and materiality, but also at the specific service offerings and methodologies used by data vendors.Footnote 60 In light of the existing variety and inconsistency, Kotsantonis and Serafeim suggest that companies should take control of the ESG data narrative, accept a baseline of ESG metrics, and self-regulate in ways that aim to provide comparability.Footnote 61 ESG disclosure driven by reporting standards of organizations such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) also plays an instrumental role in defining a ‘reasonable baseline’.Footnote 62

In general, market interest in the level of a company’s degree of transparency about its ESG performance and policies has grown continuously since the last decade.Footnote 63 Voluntary disclosure on ESG already showed lower costs of capital for those firms with superior standards, which works as an incentive for some firms.Footnote 64 A number of papers use a cross-country analysis and provide evidence of a strong relationship between the extent and the quality of a firm’s ESG disclosure.Footnote 65 Also regarding the more specific disclosure of carbon emissions it has been shown that markets penalize all firms for their carbon emissions, but an additional penalty is imposed on firms that do not disclose emission information at all.Footnote 66

Regulatory measures, such as the passage of European Union (EU) Directive 2014/95 on disclosure of non-financial information, have likewise motivated companies to provide more (and better) ESG information, as lead investors continued placing higher weight on ESG information in decision making.Footnote 67 With sustainability-related disclosures (‘Disclosure Regulation’ [EU] 2019/2088),Footnote 68 the EU requires alternative investment fund managers to, among other things, consider and document the relevance of ESG to their investment policies and produce required disclosures in this regard. In addition, when preparing or updating their staff remuneration policies (including, where required, public or investor disclosures about their remuneration practices), managers have to specify how these policies are consistent with the integration of sustainability risks.Footnote 69

2.7 ESG and Investor Behavior/Mandate

Beyond the question of how different investors integrate ESG criteria and information in their investment decision, ESG also plays a role during the holding period of an investment. As part of their portfolio-related work as equity investors (public or private), investors may be asked to vote on ESG-related matters or to engage informally to mandate sustainability-related change. The latter is also relevant for debt investors or passive funds. In the following, we first look at the literature on voting and then consider the literature focusing on other forms of investor engagement.

2.8 Voting on ESG Matters

Overall, the growth of ESG investing has contributed to a stronger focus on ESG in corporate elections. ESG-specific shareholder resolutions focus on topics such as climate change, data protection, diversity, human rights, etc. Across all fund families, asset-manager proxy voting support for ESG-related shareholder resolutions has increased considerably over the past five years, with average support across 50 large fund families rising to 46% from only 27% in 2015.Footnote 70 Funds offered by Allianz Global Investors, Blackstone, Eaton Vance and PIMCO were the most likely to support shareholder-proposed ESG resolutions in 2019, voting for these resolutions more than 87% of the time.Footnote 71

After BlackRock announced in January 2020 that it would elevate climate-related and social investment risk to its priorities,Footnote 72 researchers focused on the proxy statement of poultry processing company Sanderson Farms in Mississippi and how BlackRock, holding 10% of the company’s stock, would react to the company’s board rejecting the proposal that Sanderson Farms publicly report on climate-related water risks according to SASB standards.Footnote 73

Others explored the voting record of BlackRock and Norway Fund to assess whether institutional investors engage with companies on corporate externalities such as greenhouse gas emissions. Brière et al. found that, in general, universal ownership as well as delegated philanthropy appear to provide incentives for institutional investors to combat negative externalities generated by firms.Footnote 74

Institutional investors with higher sustainability footprints also tend to have longer investment horizons independent of whether the horizon is measured by investors’ legal types or by their trading frequency; high sustainability-footprint investors also display higher risk-adjusted performance.Footnote 75

With regard to index funds, however, Griffin shows that the three passive investment power houses Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street, while being in a new and pivotal role as the framers of market-wide governance standards,Footnote 76 show little support for E&S proposals, despite a considerable marketing focus.Footnote 77

2.9 Engagement

Apart from voting, investors also engage in other forms of ESG interventions with their firms. Concerning corporate governance, McCahery et al. have documented widespread behind-the-scenes intervention, as well as governance-motivated exits.Footnote 78 Investors face several impediments to engagement, however, principally because of liquidity concerns, free rider problems, and legal concerns. Long-term investors intervene more intensively than short-term investors, showing concerns about a firm’s corporate governance or strategy rather than about short-term issues.Footnote 79 Barko et al. show that activism is more likely to succeed when targets have a good ex ante ESG track record, lower ownership concentration and growth.Footnote 80

Stewardship codes are another approach designed to increase the consideration of ESG criteria by institutional investors; there is some evidence that this can drive improved ESG quality.Footnote 81 Dyck et al. look specifically at institutional investors and overall conclude that they drive the ESG agenda since their ownership is associated with higher firm-level E&S scores.Footnote 82 The revised UK Stewardship CodeFootnote 83 now makes explicit reference to ESG factors, and signatories are expected to take into account material ESG factors, including climate change, when fulfilling their stewardship responsibilities. The Code is written for asset owners, asset managers and entities providing services to the institutional investment community, including investment consultants, proxy advisors and other service providers that want to demonstrate their commitment to stewardship.

3 Methodology

This section first describes our survey construction and methodology. We then discuss the survey delivery method, the response rate and the characteristics of the respondents. We also describe the research design in which semi-structured interviews were used to collect qualitative data.

3.1 Survey Development and Delivery

We designed our survey to elicit responses from institutional investors and alternative asset managers on how and why they integrate ESG factors into their investment evaluation and decision-making processes. The questions concern who is responsible for considering ESG factors; how often ESG criteria are considered and in which stages of the investment decision-making and management process, and for which screening or evaluative purposes ESG criteria are employed. We also asked respondents about their motivations for using ESG criteria and how they use ESG in relation to risk and return considerations. We also asked questions to ascertain the relative importance of the environmental, social and governance components of ESG criteria. Since we are interested in how different categories of asset managers utilize ESG criteria, we have a final section requesting general and demographic information to classify our survey respondents according to investment strategy and to target asset classes, type of institutional investor, geographic location, and size of assets under management. To encourage higher response rates, we did not ask participants to identify themselves beyond these aggregate demographic statistics. We further emphasized that the individual responses would be treated as confidential.

Our questions were developed upon review of previous academic literature that conducted surveys of institutional investors concerning corporate governance and ESG-related topics.Footnote 84 We also based our survey on similar surveys conducted by industry groups and consultancies.Footnote 85

While previous research has focused on ascertaining the ESG-related preferences of institutional investors, our focus is on specific types of institutional investors, such as LPs and GPs, and their preferences for ESG investing. Additionally, we look beyond the performance considerations surrounding the use of ESG data to focus on the particular risks that these fund managers attempt to manage and mitigate by considering ESG criteria. We also look at the relative role of voice and exit with regard to ESG, further extending the work of McCahery et al.Footnote 86 and Broccardo et al.Footnote 87 to consider how investors use voice and exit in connection with ESG concerns. Furthermore, our survey was designed to unpack the individual environmental, social and governance components of ESG data to determine the relative importance of these factors for this category of investors.Footnote 88

We drafted our survey questions in consultation with academics in finance and law as well as with academic experts in survey design. We then further refined our questions after an initial round of feedback and discussions with alternative asset managers and institutional investors.

We used a combination of electronic delivery, with a link to an online survey platform, and a paper version of the survey. The online version of the survey allowed for random ordering of response choices and sub-sections of questions. The survey was distributed via an email link to a list of the authors’ personal contacts working in the asset management industry, as well as via a database of asset managers and institutional investors compiled by a research assistant and supplemented with contacts from our own industry contacts. We also distributed a paper version of the survey to distribute to the practitioner attendees at several conferences and industry events. We guaranteed anonymity in order to ensure honest responses; however, this means we were unable to map the responses to investor or fund performance metrics. A copy of the survey questions appears in Appendix B.

From a distribution to approximately 2,200 individuals, we received 106 responses. This overall response rate of 4.8% is similar to the response rates achieved in academic studies in finance.Footnote 89

3.2 Semi-Structured Interviews

To confirm, explain and otherwise contextualize some of the findings of our survey results and analysis, we conducted ten semi-structured interviews with a range of institutional investors: a US-based PE fund manager; a UK-based hedge fund manager; a portfolio manager for a multinational insurance company headquartered in continental Europe; a PE fund manager based in continental Europe; a New Zealand-based PE fund manager; three investment officers at pension fund managers based in continental Europe; an investment officer at an asset manager for pension funds and other managed accounts based in continental Europe; and an investment manager for a continental-European development bank. While the agenda and set questions for the interviews were based on our survey questions, we allowed the interview to develop according to the interviewees’ particular perspectives. We also wished to clarify the context of the particular results of our analyses of the survey data. The semi-structured interview instrument appears in Appendix C.

3.3 Methods

We consider firm characteristics as control variables, but we also focus on the geographical usage of ESG. While the majority of our analysis focuses on continental Europe, the UK and the US, we also use data from a number of countries outside of North America and Europe. The data allow us to consider investor type, broadly characterized as GPs and LPs. We classify GPs as investors who identified as a PE fund, VC fund or hedge fund. All other investor types are classified as LPs since they are primarily LPs in alternative investment managers and funds. To characterize LPs’ commitment to ESG, we view them as driving the implementation of ESG factors (which they also see as more strongly correlated with financial performance). While GPs do recognize the correlations with financial performance, they are much more motivated by client demand (i.e., demand from LPs). LPs are more likely to be motivated by the correlations with investment risk generally. However, when we ask specifically about the investors’ reputational risk (vis-à-vis stakeholders), GPs are more likely to consider ESG data. The distinction between PE and VC can be used to analyze important risk differences between start-up/earlier-stage investments in newer companies and industries and investments in more established companies.

We calculate mean responses to each answer and then use t-tests to compare motivations and barriers to each other, as well as results between categories of respondents (i.e., PEs and VCs). We create index variables by encoding and summing up responses based on how often investors use ESG for various purposes. This then enables us to perform ordered logit regressions that allow us to examine correlations among many variables simultaneously. We utilize this method to test the statistical significance, magnitude and direction of relationships, while employing control variables and examining cross-relationships among variables.

4 Summary Statistics

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the survey respondents. Our respondents represent a cross-section of investors with a tilt towards alternative asset managers. The largest group of respondents work as asset managers for PE funds (39%), followed by pension funds (19%) and VC funds (17%). The remaining comprise asset managers for pension funds, endowments and other managed accounts (13%), hedge funds (6%) and insurance companies (6%). Seventeen percent of the respondents in our sample work for those institutions with less than $1 billion in assets under management; 41% with assets between $1 billion and $20 billion; 24% with assets between $20 billion and $50 billion; and 18% with assets exceeding $50 billion. The respondents are concentrated in North America (29%), continental Europe (32%), the UK (12%) and Asia (10%), with a small percentage of respondents from South America (5%), the Middle East and Africa (6%) and Australia and New Zealand (6%). We asked respondents to report whether they have an ESG mandate—59% reported having such a mandate.

We examine the main motives for and barriers to incorporating ESG factors into the asset-allocation processes of institutional investors. To capture these motives and barriers, we asked investors to rank their top four reasons for incorporating ESG factors into their investment process. Table 2 presents some summary statistics for the sample split according to respondents’ mean rankings of motivations for and barriers to ESG usage by institutional investors. Panel A of Table 2 shows the percentage of respondents ranking the top one or two motivations for ESG usage. As Column 2 illustrates, 48% of institutional investors on average rank ESG factors related to investment riskiness as either their first or second reason for considering ESG, compared to only 13% for diversification purposes. Other important motivations for incorporating ESG factors include an explicit investment mandate, client demand, and believing ESG data to be positively correlated with investment returns. Overall, the results presented in Table 2 are consistent with the proposition that ESG usage is associated with decreased risk.Footnote 90

Our findings so far suggest that many institutional investors focus on ESG factors to evaluate financial risks when considering an investment decision and its future financial performance. To understand the challenges to ESG usage, we asked the respondents to rank the top four barriers to ESG usage, based on a five-point response scale (from ‘very important’ to ‘not important at all’). Column 3 of Panel B reports that the respondents rank the barriers to ESG usage between 2.48 to 4.37. The evidence in Panel B suggests the important role that data providers and regulators, respectively, could play in providing quality data and standardized metrics. Our findings are consistent with Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim, and Christensen et al.,Footnote 91 who claim that investors view the absences of comparable data as a major hurdle for examining firms’ ESG factors.

In Table 3, we assess the importance of ESG integration for other institutional investors, broadly characterized as GPs and LPs. The evidence suggests that investor characteristics may help explain whether some institutional investors are more likely to include ESG factors in their investment management processes.Footnote 92 Prior research documents the positive association of LPs with ESG usage and financial performance.Footnote 93 In line with this, in Table 3, Panel A, we also find evidence that while GPs recognize the correlations with financial performance, they are much more motivated by client demand (i.e., demand from LPs). In contrast, LPs are more likely to be motivated by the correlations with investment risk generally. However, we asked specifically about the investors’ reputational risk (vis-à-vis stakeholders), and the results suggest that GPs are more likely to consider ESG data in this respect.

While GPs and LPs do, on average, appear to see some links between ESG and financial performance, these links are more pronounced for LPs. GPs, on the other hand, rank client demand or client mandates as a higher motivation. So, while investors and stakeholders in pension funds, insurance companies and other asset managers (i.e., sovereign wealth funds, endowments, etc.) also demand ESG considerations with respect to alternative asset classes, GP alternative asset managers are much more driven by client demand and less so by potential linkages to risk and returns. For example, at the extreme, one London-based hedge fund manager indicated that the addition of ESG considerations in their investment process is mostly a data collection exercise to appeal to investor demand. In very few cases do ESG factors influence the actual investment decision or portfolio mix; however, LPs want the information. According to the hedge fund manager, this is not because they do not care about ESG; rather they simply rarely experience a situation in which there is sufficient ESG evidence alone to warrant a change in an investment decision based on traditional financial (i.e., non-ESG) metrics. At the same time, this sentiment is not necessarily inconsistent with the supposition that ESG metrics are correlated with financial performance.

Consistent with extant findings on barriers to ESG usage in PE, Table 3, Panel B shows that LPs also have difficulties incorporating ESG policies due to the lack of accurate and reliable data (2.37) and clear guidelines (2.77) required to facilitate predictable benchmarking and evaluation of portfolio companies.

5 Main Results

Institutional investors that weigh their portfolios toward high-ranked ESG assets reduce the risk of the investment. Through survey question 1.8, we examine how often investors use ESG in considering specific types of risks in their investment management process. Table 4 shows that, on average, the respondents rate tail risk, litigation risk and relationship risk between 1.80 and 2.21. In contrast, the risks related to compliance and portfolio company reputation are seen as somewhat less important (between 2.59 and 2.63). Interestingly, the investors in our study tend to see a correlation between ESG factors with returns and the potential to use ESG indicators as leading indicators for the future financial performance of investments. However, the evidence in Table 4 also shows that the respondents gave a much higher weight to the importance of ESG factors in measuring risks associated with investments. These results are consistent with expectations, and with the extant literature.

In Table 5, Panel A, we report on the motivations for incorporating specific risks into the investment process for a GP and an LP. To evaluate the intensity of ESG usage for specific risks, we asked investors how often, on a scale from 0 to 4, each type of risk motivates ESG considerations when making investments. The table also includes independent variables: ‘Assets under Management’ (AUM) equals one (less than $1 billion), two (between $1 billion and $20 billion), 3 (between $20 billion and $50 billion) and 4 (greater than $50 billion). ‘Active’ is the approximate percentage of assets under management invested actively versus passively. In Panel A, we use dummy variables to distinguish between GPs and LPs. We classify GPs as investors who identified as a ‘private equity fund’, ‘venture capital fund’ or ‘hedge fund’. We also control for all other investor types classified as LPs (since they are primarily LPs in alternative investment managers and funds).

Table 5, Panel A focuses on the differences across investor types in terms of ESG intensity for specific forms of investment risk. The evidence suggests that reputational risk (vis-à-vis stakeholders) is the most relevant for GPs. In general, GPs are more strongly motivated by client demand (i.e., LP demand) than by an actual perceived link between risk and returns. This is consistent with the literatureFootnote 94 that investigates the correlations of ESG factors with the riskiness of investments. As Table 5 highlights, respondents regard ESG factors as correlated with the reputational risk, regulatory risk and litigation risk associated with investments. Investors recognize that firms that invest in improving their ESG factors decrease the associated risks of fines for violating environmental regulations and, therefore, are also better prepared for coping with future tightening regulations concerning emissions, energy usage and pollution. The resulting liabilities associated with litigation and reputational damage are also mitigated by firms that proactively invest in improving ESG through investments in green energy and environmental sustainability.Footnote 95

In the case of larger companies, the evidence suggests that they care more about stakeholder risk. However, considerations of all risks drop in North America; companies with more active investments are less motivated by ESG considerations for stakeholder, litigation and tail risk. This finding supports the view that ESG is a hedge for longer-term and extreme events since more-actively-managed assets can be adapted and re-allocated quickly to such situations.

Table 5, Panel B reports that the relationship between ESG factors and risks seems to be particularly strong for alternative asset managers in the VC, PE and real estate infrastructure space. Panel B shows that regulatory risk and litigation risk are the strongest motives for VC. One possible interpretation of this finding is that the longer-term horizon of these fund managers, who know that they will not be able to exit investments for years to come, keenly understand the importance of investing in firms that are prepared for future changes in the regulatory environment. The respondents also indicate that investors in the United States are more concerned with litigation and reputation risk than non-US investors are. Empirical evidence on the significantly higher US litigation costs is consistent with analysis of our findings reported in Panel B.Footnote 96

It is noteworthy that, despite findings of strong empirical evidence for a correlation between tail risk and ESG for public equities,Footnote 97 our survey respondents indicated that this is their least motivating risk factor for using ESG when evaluating alternative assets. The evidence suggests that these investors are most likely using ESG as a hedge for various regulatory and litigation risks.Footnote 98

It appears from the above analysis that institutional investors attach a higher importance to the role of ESG factors in mitigating tail risk and regulatory risk with respect to investments in their alternative asset portfolios.

5.1 Using ESG Data in the Investment Process

It is widely known that ESG data can convey material information that is related to financial performance.Footnote 99 To understand how investors use ESG factors in the investment management process, we asked our participants to rank, in Question 1.7, each of the following purposes: screening criteria for exclusion of new investments; weight towards/away/completely exit existing investments; indicator of future financial returns; indicator of riskiness of investment; for benchmarking purposes; and engaging the company in ESG issues. We asked respondents to answer the question on a scale from ‘never’ (score of 0) to ‘always’ (score of 4). Table 6 reports that respondents’ strongest motives for using ESG data are for the purposes of benchmarking (1.92) and conveying some information about future financial performance (1.36). The results above are consistent with the hypothesis that investors are more likely to use ESG to measure financial issues.

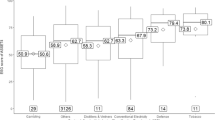

We now examine the intensity of GP and LP usage of ESG factors in their investment management process. The regressions are reported in Table 7. We start by noting that there is little direct relationship between AUM and the intensity of ESG usage (models 1–3). However, our estimates suggest that GPs are statistically more likely to have higher ESG intensity (model 4), but this is largely correlated with geography, with US funds using ESG less intensively than UK funds, and both using it less intensively than continental European funds (model 5). Focusing on funds from the rest of the world (ROW), the estimates suggest that ROW funds use ESG more often than US, UK and European funds. There are a number of reasons why we might expect to see some companies embrace ESG strategies. One possibility is that a company’s strategic commitment to ESG goals may signal to investors that it is a high-quality company. Second, it is possible that it is simply a function of the large amount of capital being directed toward impact investing, which may benefit companies strongly affected by a positive investment environment. Models 6-7 report that PE funds use ESG more intensely than VC funds do, regardless of geography, though, again, US funds use ESG markedly less intensively (model 7). From the above analysis, it appears that the GP/LP distinction can also be interpreted as less-intense usage for earlier-stage investments.

To further examine the drivers of ESG intensity, we estimate regression models in Table 8, where the dependent variables are the rankings of respondents’ perceived motivations for and barriers to ESG usage of six topics. The dependent variables in Columns 1 to 3 are respondents’ rankings for explicit mandate, client demand, and ethics as motivations for ESG usage. In Columns 4 to 6, the dependent variables are the respondents’ rankings for lack of standardized data, lack of reliable data, and poorly defined ESG factors as barriers to ESG usage. The values for all dependent variables range between one and five, and lower values indicate a more important motivation in Columns 1 to 3 and a more important barrier in Columns 4 to 6. The results reported in Table 8 indicate that data availability and ethics motivations provide the greatest support to the stakeholder demand hypothesis. Our results conform to the view that multinational enterprises operating in developing countries adopt more stringent environmental standards to signal companies’ ESG responsiveness and, therefore, are more likely to be valued positively.Footnote 100

5.2 Voice and Exit Related to ESG

In this section, we focus on the complementary use of voice and exit strategies by PEs and VCs with respect to their alternative investments. Table 9 shows the results of ordered logit regressions. The dependent variable intensity of ESG voice is an index based on the response to survey question 1.7(6), which asked respondents how often they engage companies (either directly or via GP/fund manager) in ESG-related issues. Interestingly, our results indicate that there is no statistically significant relationships between firm size (AUM) and the active share of the portfolio that uses voice and exit with respect to ESG considerations (models 1-3).

The second noteworthy finding is that the exit and voice channels are more often used by GPs (models 3, 5 and 8). This makes sense since they are more directly engaged in companies and ultimately have the power to directly exit a company investment. Although our interviews do confirm that LPs will still address ESG concerns about a particular company with a GP, this is only for egregious reasons. Instead, most discussions with GPs about ESG characteristics focus on the fund level. In the main, most exit and voice interactions occur directly between GPs and target companies. This raises the issue of whether the implicit threat of exit by non-participation in subsequent funds and co-investment opportunities means the exit-voice interactions can and do still occur between LPs and GPs. However, our interviewees tell us this is generally understood as a means to pressure the GP to directly engage with the company.

On the other hand, we can see an analogy to the argument advanced by Bebchuck et al.Footnote 101 that large institutional investors are incentivized to side with management on issues related to the public equities they hold. Consistent with this argument, LPs’ incentives are presumably aligned with GPs. Though we know from our interviews and our analysis here that GPs do engage directly with companies on ESG issues, these issues are generally of secondary concern and depend on how egregious the ESG concerns are. Instead, GPs may try to manage ESG at the fund level; similarly, LPs generally manage ESG concerns at the aggregate portfolio level. GPs and LPs can shuffle exposure internally among funds/accounts to ensure that ultimate investors/stakeholders’ desired ESG profiles are met.

We also find that PEs use voice and exit more often than VCs do (models 4, 6 and 9). This makes sense since earlier-stage VC investments are generally less liquid than later-stage PE investments, and the focus of many interactions with nascent companies may also take a longer-term perspective on developing ESG. To be sure, this should not discount the role that voice and exit play with respect to ESG considerations, as it is statistically significant, but less so than with PE fund managers.

It is interesting to note that, geographically, exit and voice due to ESG concerns are used less frequently only in North America (models 5, 6, 8 and 9 in Table 9) and, even then, are not universally robust and statistically significant across all models. Nonetheless, this is generally consistent with our other findings showing that, while still important, ESG is generally less important to US-based investors than to their counterparts in the rest of the world. These results are also consistent with survey results related to ESG considerations in the public-equities space.Footnote 102

Furthermore, we document that GPs use exit and voice more often than LPs. While our interview evidence confirms that LPs will address ESG concerns about a particular company with a GP, this is only for egregious concerns. Our findings highlight, among other things, that LPs do not have the same significant effect on governance that GPs have.

5.3 Relative E, S and G Preferences

The results above demonstrate the importance of investors’ engagement strategies to address ESG concerns about a particular company. In this section, we examine investors’ beliefs about the relative importance of E, S and G scores individually. Table 10, Panel A reports our findings on investors’ preferences with respect to the individual E, S and G components. The respondents, on average, rate the three components between 1.82 and 2.46, which means that G is considered important.

The results reported in Table 10, Panel B indicate that G is more important to larger institutional investors. Our findings conform with recent empirical studies showing that institutional investors generally, and the Big Three in particular, are not only drawn to all firms with higher ESG scores, but are most significantly drawn to firms with high G scores.Footnote 103

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we present the results of our survey of institutional investors and alternative asset managers to better understand the challenges and opportunities of incorporating ESG into their investment management processes. Our new data set is constructed based on a 2020 survey of 106 institutional investors from Europe and North America, as well as a small percentage of respondents from around the world. Our data allow us to shed light on the intensity and use of ESG by LPs and PE and VC firms. First, we find that LPs are motivated to incorporate ESG, because they believe that ESG usage is more strongly correlated with financial performance. GPs are motivated to integrate ESG factors into their investment strategies in response to increased client demand for sustainable products. Second, we find that PE firms use ESG factors more intensively than VC firms regardless of geography. Third, we consider that investors can choose between voice and exit in their approach to ESG investing. We find that PE funds use voice and exit strategies more extensively than VC funds in efforts to promote ESG activities in companies. Finally, we find that the investors consider that the governance score is the most important component of ESG.

The findings of this paper make three contributions to the literature. First, the paper provides new insights into the importance that LPs and GPs place on ESG, highlighting the motivations for and barriers to ESG usage. Second, we contribute to the literature on ESG integration by PE and other alternative asset classes by showing that PE firms are more likely than VC firms to use ESG more intensively, regardless of where the alternative asset managers are located. Third, we contribute to the literature on investor engagement on ESG by analyzing the use of voice and exit by LPs and GPs and through our findings that PEs use voice and exit more often than VCs.

Notes

Natixis Investment Managers (2021).

OECD (2020).

Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2022) consider these relative preferences for institutional investors in publicly traded securities.

For a general overview of themes in the ESG-related literature, see Gillan et al. (2021).

Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018).

Heinkel et al. (2001).

Statman and Glushkov (2009).

Gibson et al. (2020).

Starks et al. (2017).

The term ‘sin stocks’ commonly refers to a publicly traded company that is either involved in or associated with an activity that is considered unethical or immoral such as the production of alcohol, tobacco or weapons.

One way to classify different investment styles while at the same time explaining how an investor is making use thereof is shown by NN Investment Partners (2019) in their Responsible Investing Report 2019.

Clark et al. (2015).

This study uses the term ‘sustainability’ as an equivalent for ESG. In general, terms such as ‘sustainability’, ‘environmental, social and governance (ESG)’, as well as ‘corporate social responsibility’ (CSR) have been used interchangeably in the past, although they can mean different things. On the lack of a definition of sustainability, see Gray (2010).

Clark et al. (2015).

Friede et al. (2015).

Bialkowski and Starks (2016).

Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018).

Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018).

Bialkowski and Starks (2016).

Hamilton (1995).

Dasgupta et al. (2001).

Hoepner et al. (2018).

Hanson et al. (2017).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Verheyden et al. (2016).

Sherwood and Pollard (2018).

PRI Association (2018).

United Nations (2022).

Tang and Zhang (2018).

Martin and Moser (2016).

Renneboog et al. (2008).

Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (2018).

Hainmueller et al. (2015).

Zerbib (2019).

Dowell et al. (2000).

See also Derwall et al. (2005).

Brammer et al. (2006).

Love (2011).

Fama and French (2007).

Heinkel et al. (2001).

Chatterji and Toffel (2010).

McWilliams and Siegel (2001). The authors use the term ‘CSR’ though.

Clark et al. (2015).

Eccles et al. (2011).

Khan et al. (2016).

Daines et al. (2010).

Delmas et al. (2013).

Eccles and Stroehle (2018).

Kotsantonis and Serafeim (2019).

Ibid.

Eccles et al. (2011).

Dhaliwal et al. (2011).

Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2020).

Matsumura et al. (2013).

Grewal et al. (2019).

European Union (2019).

Maleva-Otto and Wright (2020).

Cook (2020).

Cook and Hale (2020).

Fink (2020).

Rissman (2020).

Brière et al. (2018).

Gibson and Krüger (2017).

Griffin (2020a).

Griffin (2020b).

McCahery et al. (2016).

Ibid.

Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2022).

Dyck et al. (2019).

UK Financial Reporting Council (2019).

McCahery et al. (2016).

Broccardo et al. (2022).

Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2022).

Krueger et al. (2019).

Dyck et al. (2019).

Berger-Walliser et al. (2016).

Lawyers for Civil Justice (2015).

Bebchuk et al. (2017).

Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2022).

References

Albuquerque RA, Koskinen YJ, Yang S, Zhang C (2020) Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: an analysis of the exogenous COVID-19 market crash. Rev Corp Fin Stud 9(3):593–621

Amel-Zadeh A, Serafeim G (2018) Why and how investors use ESG information: evidence from a global survey. Fin Anal J 74(3):87–103

Amon J, Rammerstorfer M, Weinmayer K (2021) Passive ESG portfolio management: the benchmark strategy for socially responsible investors. Sustainability 13:9388. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/16/9388/pdf?version=1629776946. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Baker M, Bergstresser D, Serafeim G, Wurgler J (2018) Financing the response to climate change: the pricing and ownership of U.S. green bonds. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Wurgler-J.-et-al..pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Bansal R, Wu D, Yaron A (2018) Is socially responsible investing a luxury good? https://rodneywhitecenter.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/13-18.Yaron_.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Barber B, Morse A, Yasuda A (2021) Impact investing. J Fin Econ 139(1):162–185

Barko T, Cremers M, Renneboog L (2021) Shareholder engagement on environmental, social, and governance performance. J Bus Ethics 180:777–812. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-021-04850-z. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Barnett M, Salomon R (2006) Beyond dichotomy: the curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strat Mgmt J 27(11):1101–1122

Barnett M, Brock W, Hansen LP (2020) Pricing uncertainty induced by climate change. Rev Fin Stud 33(3):1024–1066

Bebchuk LA, Cohen A, Hirst S (2017) The agency problems of institutional investors. J Econ Persp 31(3):89–112

Becchetti L, Ciciretti R, Hasan I (2015) Corporate social responsibility, stakeholder risk, and idiosyncratic volatility. J Corp Fin 35(5):297–309

Berger-Walliser G, Shrivastava P, Sulkowski A (2016) Using proactive legal strategies for corporate environmental sustainability. Mich J Environ & Admin L 6(1):1–35

Bfinance (2017) ESG asset owner survey: how are investors changing? https://www.bfinance.com/insights/esg-asset-owner-survey-how-are-investors-changing/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Bialkowski J, Starks LT (2016) SRI funds: investor demand, exogenous shocks and ESG profiles. https://ideas.repec.org/p/cbt/econwp/16-11.html. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

BNP Paribas (2019) ESG global investor survey 2019. https://securities.cib.bnpparibas/app/uploads/sites/3/2021/03/ss-brochure-esg-global-survey-2019.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Bolton P, Halem Z, Kacperczyk M (2022) The financial cost of carbon. J Appl Corp Fin 34(2):17–29

Borgers A, Derwall J, Koedijk K, Ter Horst J (2015) Do social factors influence investment behavior and performance? Evidence from mutual fund holdings. J Bank Fin 60:112–126

Brammer S, Brooks C, Pavelin S (2006) Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Fin Mgmt 35(3):97–116

Brandon GR, Krueger P, Schmidt PS (2021) ESG rating disagreement and stock returns. Fin Anal J 77(4):104–127

Brav A, Graham JR, Harvey CR, Michaely R (2008) Managerial response to the May 2003 dividend tax cut. Fin Mgmt 37(4):611–624

Brière M, Pouget S, Ureche-Ragnar L (2018) BlackRock vs Norway Fund at shareholder meetings: institutional investors’ votes on corporate externalities. http://ssrn.com/abstact_id=3140043. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Broccardo E, Hart O, Zingales L (2022) Exit vs. voice. J Pol Econ (forthcoming). https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hart/files/exit_vs_voice_1230.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Capital Group (2022) ESG Global Study 2022. https://coredatainsights.com/client-insights/capital-group-esg-global-study-2021/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Chatterji A, Toffel M (2010) How firms respond to being rated. Strat Mgmt J 31:917–945

Chatterji A, Durand R, Levine D, Touboul S (2016) Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strat Mgmt J 37(8):1597–1614

Chen F, Ngniatedema T, Li S (2018) A cross-country comparison of green initiatives, green performance and financial performance. Mgmt Dec 56(5):1008–1032

Christensen D, Serafeim G, Sikochi A (2021) Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder? The case of ESG ratings. Acct Rev 97(1):147–175

Clark GC, Feiner A, Viehs M (2015) From the stockholder to the stakeholder. How sustainability can drive financial outperformance. https://arabesque.com/research/From_the_stockholder_to_the_stakeholder_web.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Clayman MR (2015) The benefits of socially responsible investing: an active manager’s perspective. J Inv 24(4):49–72

Cook J (2020) How fund families support ESG-related shareholder proposals. http://www.morningstar.com/insights/2020/02/12/proxy-votes. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Cook J, Hale J (2020) 2019 ESG proxy voting trends by 50 U.S. fund families. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/03/23/2019-esg-proxy-voting-trends-by-50-u-s-fund-families/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Cornell B, Damodaran A (2020) Valuing ESG: doing good or sounding good? J Impact & ESG Inv 1(1):76–93

Daines RM, Gow ID, Larcker DF (2010) Rating the ratings: how good are commercial governance ratings? J Fin Econ 98(3):439–461

Dasgupta S, Laplante B, Mamingi N (2001) Pollution and capital markets in developing countries. J Environl Econ Mgmt 42(3):310–335

De I, Clayman MR (2015) The benefits of socially responsible investing: an active manager’s perspective. J Invest 24(4):49–72

Delmas MA, Etzion D, Nairn-Birch N (2013) Triangulating environmental performance: what do corporate social responsibility ratings really capture? Acad Mgmt Persp 27(3):255–267

Derwall J, Gunster N, Bauer R, Koedijk K (2005) The eco-efficiency premium puzzle. Fin Anal J 61(2):51–63

Dhaliwal D, Li O, Tsang A, Yang YG (2011) Voluntary disclosure and the cost of equity capital: the initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Acct Rev 86(1):59–100

Dichev ID, Graham JR, Harvey CR, Rajgopal S (2013) Earnings quality: evidence from the field. J Acct Econ 56:1–33

Dowell G, Hart S, Yeung B (2000) Do corporate global environment standards create or destroy market value? Mgmt Sci 46:1059–1074

Dyck A, Lins K, Roth L, Wagner H (2019) Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International Evidence. J Fin Econ 131(3):693–714

Eccles R, Serafeim G, Krzus M (2011) Market interest in nonfinancial information. J Appl Corp Fin 23(4):113–127

Eccles RG, Stroehle J (2018) Exploring social origins in the construction of ESG measures. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3212685. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

European Union (2019) Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability‐related disclosures in the financial services sector (Text with EEA relevance). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019R2088&from=EN. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

EY (2021) EY Global Institutional Investor Survey. https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/assurance/assurance-pdfs/ey-institutional-investor-survey.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

FTSE Russell (2018) Sustainable investment: global asset owner survey. https://www.ftserussell.com/index/spotlight/sustainable-investment-2021-global-survey-findings-asset-owners. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Factica S, Panzica R, Rancan M (2021) The pricing of green bonds: are financial institutions special? J Fin Stab 54. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1572308921000334. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Fama EF, French KR (2007) Disagreement, tastes, and asset prices. J Fin Econ 83(3):667–689

Fink L (2020) Larry Fink’s 2020 letter to CEOs: fundamental reshaping of finance. https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/2020-larry-fink-ceo-letter. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Flammer C (2013) Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reactions: the environmental awareness of investors. Acad Mgmt J 56(3):758–781

Friede G, Busch T, Bassen A (2015) ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J Sust Fin Inv 5(4):210–233

Geczy CC, Stambaugh RF, Levin D (2005) Investing in socially responsible mutual funds. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1444&context=fnce_papers. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Gibson R, Krüger P (2017) The sustainability footprint of institutional investors. https://ecgi.global/sites/default/files/working_papers/documents/finalbrandonkruger1.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Gibson R, Glossner S, Krueger P, Matos P, Steffen T (2020) Do responsible investors invest responsibly? Rev Fin (forthcoming). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3525530. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Gillan SL, Koch A, Starks LT (2021) Firms and social responsibility: a review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J of Corp Fin 66. https://www.sustainablebusiness.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/gillan_koch_starks_2020_-_working_paper_-_csr_review_1.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Goldstein I, Kopytov A, Shen L, Xiang H (2022) On ESG investing: heterogeneous preferences, information, and asset prices. https://finance.wharton.upenn.edu/~itayg/Files/esgtrading.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Gray R (2010) Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Acct Org Soc 35(1):47–62

Grewal J, Riedl E, Serafeim G (2019) Market reaction to mandatory nonfinancial disclosure. Mgmt Sci 65(7):3061–3084

Griffin CN (2020a) We three kings: disintermediating voting at the index fund giants. Maryland L Rev 79(4):954–1008

Griffin CN (2020b) Environmental & social voting at index funds. Del J Corp L 44:167–222

Hainmueller J, Hiscox M, Sequeira S (2015) Consumer demand for fair trade: evidence from a multistore field experiment. Rev Econ Stat 97(2):242–256

Hamilton JT (1995) Pollution as news: media and stock market reactions to the toxic release inventory data. J Environ Econ Mgmt 28:98–113

Hanson D, Lyons T, Bender J, Bertocci B, Lamy B (2017) Analysts’ roundtable on integrating ESG into investment decision-making. J Appl Corp Fin 29:44–55

Heinkel R, Kraus A, Zechner J (2001) The effect of green investment on corporate behavior. J Fin and Quan Anal 36:431–449

Hoepner AGF, Oikonomou I, Sautner Z, Starks LT, Zhou X (2018) ESG shareholder engagement and downside risk. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2874252. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Hong H, Kacperczyk M (2009) The price of sin: the effects of social norms on markets. J Fin Econ 93:15–36

Karpf A, Mandel A (2018) The changing value of the ‘green’ label on the US municipal bond market. Nat Clim Change 8:161–165

Khan M, Serafeim G, Yoon A (2016) Corporate sustainability: first evidence of materiality. Acct Rev 91(6):1697–1724

Klassen RD, McLaughlin CB (1996) The impact of environmental management on firm performance. Mgmt Sci 42(8):1199–1214

Konar S, Cohen MA (2001) Does the market value environmental performance? Rev Econ Stat 83(2):281–289

Kotsantonis S, Serafeim G (2019) Four things no one will tell you about ESG data. J Appl Corp Fin 31(2):50–58

Krueger P, Sautner Z, Starks LT (2019) The importance of climate risks for institutional investors. https://ecgi.global/sites/default/files/working_papers/documents/finalkruegersautnerstarks.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Lawyers for Civil Justice (2015) Litigation cost survey of major companies. https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/litigation_cost_survey_of_major_companies_0.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Lopez-de-Silanes F, McCahery JA, Pudschedl PC (2020) ESG performance and disclosure: a cross-country analysis. Singapore J L Stud 1:217–242

Lopez-de-Silanes F, McCahery JA, Pudschedl PC (2022) Institutional investors and ESG preferences. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4049313. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Love I (2011) Corporate governance and performance around the world: what we know and what we don’t. World Bank Res Obs 26(1):42–70

Maleva-Otto A, Wright J (2020) New ESG disclosure obligations. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/03/24/new-esg-disclosure-obligations/#1b. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Martin P, Moser D (2016) Managers’ green investment disclosures and investors’ reaction. J Acct Econ 61(1):239–254

Matsumura EM, Prakash R, Vera-Muñoz SC (2013) Firm-value effects of carbon emissions and carbon disclosures. Acct Rev 89(2):695–724

McCahery JA, Sautner Z, Starks LT (2016) Behind the scenes: the corporate governance preferences of institutional investors. J Fin 71(6):2905–2932

McWilliams A, Siegel D (2001) Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad Mgmt Rev 26(1):117–127

Morrow Sodali (2020) Institutional Investor Survey 2020. https://morrowsodali.com/uploads/insights/attachments/83713c2789adc52b596dda1ae1a79fc2.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

MSCI (2018) Investment insight 2018. https://www.msci.com/our-clients/asset-owners/investment-insights-report. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Natixis Investment Managers (2021) ESG Investor Insights Report. https://www.im.natixis.com/intl/resources/2021-esg-investor-insight-report-executive-overview. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

NN Investment Partners (2019) Responsible Investing Report 2019. https://www.nnip.com/en-INT/professional/themes/responsible-investing-report-2019. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

OECD (2020) Business and finance outlook 2020: sustainable and resilient finance. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/b854a453-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/b854a453-en. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Pastor L, Stambaug RF, Taylor LA (2021) Sustainable investing in equilibrium. J Fin Econ 142(2):550–571

PRI Association (2018) Principles for responsible investment, financial performance of ESG integration in US investing. https://www.unpri.org/fixed-income/the-pris-esg-and-alpha-study/2740.article. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Renneboog L, Ter Horst J, Zhang C (2008) Socially responsible investments: institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. J Bank Fin 32(9):1723–1742

Riedl A, Smeets P (2017) Why do investors hold socially responsible mutual funds? J Fin 72(6):2505–2550

Rissman P (2020) BlackRock and the curious case of the poultry farmer. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/03/10/blackrock-and-the-curious-case-of-the-poultry-farmer/. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Sautner Z, van Lent L, Vilkov G, Zhan R (2022) Pricing climate change exposure. Mgmt Sci (forthcoming). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3792366. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Shafer M, Szado E (2020) Environmental, social, and governance practices and perceived tail risk. Acct Fin 60(4):4195–4224

Sherwood MW, Pollard JL (2018) The risk-adjusted return potential of integrating ESG strategies into emerging market equities. J Sust Fin Inv 8(1):26–44

Starks LT, Venkat P, Zhu Q (2017) Corporate ESG profiles and investor horizons. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3049943. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

State Street Global Advisors (2017) ESG institutional investor survey, performing for the future. https://www.ssga.com/investment-topics/environmental-social-governance/2017/esg-institutional-investor-survey-us.PDF. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Statman M, Glushkov D (2009) The wages of social responsibility. Fin Anal J 65:33–46

Tang DY, Zhang Y (2018) Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? J Corp Fin. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.12.001

Trinks PJ, Scholtens B (2017) The opportunity cost of negative screening in socially responsible investing. J Bus Ethics 147:193–208

UK Financial Reporting Council (2019) Proposed revision to the UK Stewardship Code. https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/bf27581f-c443-4365-ae0a-1487f1388a1b/Annex-A-Stewardship-Code-Jan-2019.pdf. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

United Nations (2022) 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/en/exhibits/page/sdgs-17-goals-transform-world. Accessed 3 Oct 2022

Verheyden T, Eccles RG, Feiner A (2016) ESG for all? The impact of ESG screening on return, risk, and diversification. J Appl Corp Fin 28(2):47–55

Zerbib OD (2019) The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: evidence from green bonds. J Bank Fin 98:39–60

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Tables

Table 1 provides summary statistics of the 106 survey respondents. Demographic data include institutional investor type (survey question 2.1); size measured in US dollar amount of assets under management (survey question 2.4); the approximate percentage of assets under management invested actively versus passively (survey question 2.3); geographic headquarters of institutional investor (survey question 2.2); the position title or titles of the primary person or persons responsible for the ESG factors in the investment process (survey question 1.1); the type of any ESG-related mandates the investor has (survey question 1.3); and the overall style of ESG usage in the investment process (survey question 1.4).

Table 2—Panel A presents survey respondents’ rankings of their top four motivations for incorporating ESG into the investment management process (survey question 1.5). Table 2—Panel B presents the survey respondents’ rankings of what they perceive as the top four barriers to ESG usage (survey question 1.6). A response of ‘1’ indicates that the topic is the most important to the respondent. Responses with fewer than four rankings were permitted. Column 1 reports the percentage of respondents who ranked the topic as number ‘1’; Column 2 reports the percentage of respondents who ranked the topic as either ‘1’ or ‘2’. For statistical calculations in Columns 3-5, unranked topics were assigned a rank of ‘5’, Column 3 presents the mean rank for that topic. Lower mean ranks imply that the topic is more important, on average, to the respondents (i.e., a bigger motivation for survey question 1.5 or a bigger barrier for survey question 1.6). Column 4 presents the results of a t‐test of the null hypothesis that the mean rank for each topic is equal to ‘5’ (*** indicate significance at the 1 percent level). Column 5 presents the results of a t‐test of the null hypothesis that the mean rank for a given topic is equal to the mean rank for each of the other topics, where significant differences at the 10% level are reported.