Abstract

Shareholder engagement has come to be seen to be pivotal to good corporate governance. It is therefore more important than ever for the mechanisms of shareholder engagement to be up to the important task they are meant to perform. Historically, these mechanisms have fallen short because of the capital markets’ necessary dependency on custody chains. Custody chains perform valuable functions but they also create a distance between the company and the end investor from which flows a significant risk of voting preferences and other important information not passing smoothly up and down the chain. Corporate governance is thus at risk of being distorted by process deficiencies. Changes to the operation of custody chains that were introduced by the EU’s flagship amended Shareholder Rights Directive II became operative in September 2020. This article is therefore among the first to draw on operational impact to assess the significance of these new measures. Experience has already demonstrated that while there have been some important advances, the regulatory changes are struggling on two levels: they have created new uncertainties within national laws; and they have failed to provide the necessary cross-border harmonization of key concepts. These are not issues that can be resolved effectively by technology or market workarounds on their own. There is a continuing need for legislative change to ensure that legal uncertainties do not act as a barrier to further technology-driven market standardization and innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Custody chains complicate shareholder engagement by interposing several layers of intermediaries between companies and their end investors. Corporate governance-related problems with custody chains exist in major markets around the world. This article focuses on the situation in Europe, by which is meant the EU/EEA and also the UK.

The EU’s flagship amended Shareholder Rights Directive II (2017) addresses the operation of custody chains. The changes became operative in September 2020 and this article is therefore among the first to draw on operational impact to assess the significance of the new measures. Unfortunately, experience has already demonstrated that while there have been some important advances, the regulatory changes are struggling on two levels: they have created new uncertainties within national laws; and they have failed to provide the necessary cross-border harmonization of key concepts. These are not issues that can be resolved effectively by technology or market workarounds on their own. Rather, they need to be addressed at the legislative level to ensure that legal uncertainties do not act as a barrier to further technology-driven market standardization and innovation.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 outlines the rise of shareholder engagement because this trend has made it all the more important to ensure that the mechanisms of shareholder engagement work well. Section 3 considers the importance of custody chains to the functioning of international capital markets and why, notwithstanding their many benefits, they can act as a barrier to effective shareholder engagement. Section 4 examines the new EU measures and the main problems that have emerged. Section 5 explains why we cannot look to technology to provide quick fixes to what are fundamental conceptual problems and identifies key areas that require legislative intervention. Section 6 concludes.

2 The Rise of Shareholder Engagement

Shareholder engagement has become an increasingly important part of corporate governance since the start of the 21st century. This trend towards greater emphasis on shareholder engagement is attributable to a mix of business and regulatory factors. The following sections elaborate.

2.1 Why Activist, Active and Passive Funds May Choose to Engage

Engagement with investee companies to increase their value emerged by the mid-2000s as a core part of the business strategy of activist hedge fund investors.Footnote 1 Engagement has always been key to the investment strategies of private equity and venture capital funds.Footnote 2 General investment funds are also looking at engagement as a way both to distinguish themselves from competitors and to improve investment returns.Footnote 3 Active fund managers whose business model involves actively buying, selling and holding securities are investing in building up engagement capabilities (in Hirschman’s classic framework,Footnote 4 using ‘voice’ to complement ‘exit’).Footnote 5

Active funds are being challenged competitively by the rise of lower-cost index funds whose portfolios are constructed to track the components of a financial market index.Footnote 6 (The market share of index funds in the EU stands at just 16 per cent compared to over 50 per cent for equity-linked US mutual funds but enhanced European growth in passive vehicles is anticipated, with predictions of a 30 per cent share during this decade, of which a significant proportion is expected to be in exchange-traded funds.Footnote 7) Superficially, the rise of passive tracker funds could be viewed as a trend that runs counter to the growing emphasis on engagement because the low-cost business model suggests a strong likelihood of underinvestment in stewardship. On the other hand, while the low-cost business model of passive funds militates against investment in engagement, being tied to an index removes the option of discretionary exit and thus suggests a stronger dependency on engagement/voice than active funds which may limit their investment in engagement precisely because they have the option of exit available to them.

An obvious disincentive for any fund – active or passive – to engage in engagement activities is that it will not fully capture the benefit of that activity to the exclusion of other ‘free rider’ investors. There is a growing body of empirical literature exploring whether there is underinvestment in stewardship by funds due to weak incentives and costs.Footnote 8 Notwithstanding the widespread scepticism about incentives to invest, there is some evidence that funds do view stewardship capabilities as a source of competitive advantage.Footnote 9 With growing public understanding of the climate crisis changing what individuals expect of the institutional investors that manage their long-term savings, managers of funds are likely to see more reason to burnish their credentials as agents for positive change on environmental, social and governance matters (collectively ESG) through shareholder engagement.Footnote 10 It makes sense for funds with diversified portfolios to direct their stewardship efforts towards market-wide externalities.Footnote 11

2.2 Retail Investors Wanting a ‘Say’

After years of decline,Footnote 12 direct retail investment in equities and participation in voting and other forms of shareholder engagement are also experiencing an upturn in some countries,Footnote 13 although this has not yet extended to the EU.Footnote 14 Overall, retail investment represents a small portion of the capital markets, and retail participation in voting is at a much lower level than that of institutional and professional investors,Footnote 15 but these considerations notwithstanding, recent analysis focused on the US market has found that retail shareholders can be an influential voting bloc.Footnote 16 The European Commission has recently cited growing interest among citizens, especially young people, in having a say in how companies are run, notably as regards sustainability issues, as a factor shaping its policy thinking on the operation of custody chains.Footnote 17 A campaign to give shareholders a ‘say on climate’ akin to their ‘say on pay’ is attracting some powerful advocates, including the UN Secretary-General and a former Governor of the Bank of England, and some prominent companies such as Unilever, Glencore and Moody’s are already doing this.Footnote 18 The stunning success in 2021 of Engine No 1, a small activist investment fund, in winning a proxy contest for three board seats at Exxon Mobil via a relatively modest $30 million campaign that included a website, Twitter posts, employee forums and television appearances, is a high-profile example of how coordinated efforts by investors can alter the corporate governance landscape.Footnote 19 Over time, the development of blockchain-based and/or application programming interface (API) digital technologies could help retail investors to become an increasingly important part of this trend.Footnote 20

2.3 Shareholder Engagement as an Instrument of Financial Regulatory Policy

On the regulatory side, investment intermediaries’ duties to act in the interests of their clients and related supervisory expectations on what is needed for markets to function well increasingly encompass engagement with investee companies and the making of considered decisions about the exercise of voting discretions.Footnote 21 Transparency obligations on institutional investors, asset managers and proxy advisers with respect to their engagement with investee companies, including mandatory disclosures relating to policies on voting and information about the actual casting of votes, are becoming progressively more demanding. The 2017 version of the Shareholder Rights Directive represented a step-change for Europe in this respect.Footnote 22 (Changes to the operation of custody chains that were also introduced by the revising Directive are the primary focus of this article.) New mandatory sustainability-related disclosure requirements for the investment industry are being introduced.Footnote 23 Baseline formal obligations, the details of which vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction but which typically do not extend to a specific legal obligation to undertake stewardship activities (though general duties to act in the interests of clients may require consideration of stewardship in particular circumstances),Footnote 24 are bolstered by soft law ‘comply or explain’/’apply and explain’ stewardship codes that were first introduced to address perceived problems of short-termism and excessive passivity on the part of institutional investors.Footnote 25 The first stewardship code was published in the UK in 2010, and other countries, including the United States in 2017, have since adopted their own versions.Footnote 26 Transnational bodies have also produced stewardship codes.Footnote 27 Stewardship codes seek to set high standards for the investment intermediary ecosystem, by which is meant those that invest money on behalf of savers and pensioners and those that support them. The ecosystem includes pension fund trustees and insurers (in this context often described as asset owners), asset managers and service providers, such as proxy advisers and investment consultants. Doubts as to the effectiveness of codes in driving responsible stewardship and about their suitability for markets where the US/UK institutional investor-dominated share ownership model is not prevalent have not inhibited the global rise of stewardship codes.Footnote 28

3 Custody Chains Complicate the Engagement Landscape

Custody chains are largely a by-product of the organization of modern systems for trading, clearing and settlement of securities. Publicly traded securities increasingly exist only in dematerialized, book entry form and are typically held within central securities depositories (CSDs). Settlement of trades via a CSD results in securities being recorded to the account of a CSD member. Some CSDs allow individual investors to have their own direct account with the CSD but this a relatively unusual (and often quite expensive) option.Footnote 29 More typically, there will be a custody chain involving the CSD, the CSD member, such as a custodian bank, to whose account the securities are credited, and then further intermediaries until the chain eventually reaches the end investor. Intermediaries typically use ‘omnibus’ accounts to hold securities on behalf of multiple investors.

These well-established market arrangements provide the cross-border links between national/regional financial market infrastructures that enable investors to hold internationally-diversified portfolios securely, efficiently and cost-effectively. For a typical investor, directly accessing a large number of national CSDs in order to access securities in different jurisdictions is unlikely to be a realistic option.Footnote 30 A further advantage of holding securities in CSDs via custodians is that this can provide access to intraday credit facilities and to a range of asset servicing and financial collateral intermediary services. However, despite their undoubted benefits, custody chains complicate shareholder participation in corporate governance by interposing several layers of intermediaries between companies and their end investors. The complexities are usually intensified in the case of cross-border chains, both because such chains are likely to have more links than a purely domestic chain and because different national laws and market practices are involved.

A range of issues arises at the intersection of custody chains and corporate governance.Footnote 31 Custody chains provide end investors with access to intermediary services that in theory should help them to manage participation in general meetings and corporate actions, but practical problems to do with the timely flow of communications to and from companies and their end investors through the chain of intermediaries mean that reality sometimes falls short. On the whole, corporate action processes work reasonably well, in particular the cascading of dividends and interests payments down the custody chain, but in spite of the tremendous capabilities of modern technologies, cumbersome mechanisms for communicating voting and related general meeting matters can still persist, especially for retail investors.Footnote 32 Investors may find that they have to pay significantly for the privilege of engagement through the charging by their intermediaries of extra fees for voting and other shareholder services.Footnote 33 Investors may also have to take extra steps, such as the lodging of paper powers of attorney, just to establish their eligibility to vote remotely. There can also be more fundamental legal complexities associated with identifying exactly where in the chain control of shareholder rights is located.

In a simple non-intermediated world, an investor in shares directly acquires a bundle of shareholder rights, including voting rights and the right to benefit from corporate actions such as the payment of dividends, stock splits, rights issues and takeover offers. If this allocation of rights were transposed directly into the intermediated world, the control of shareholder rights would sit with the end investor.Footnote 34 Contractual arrangements along the chain would be designed to achieve this effect where it does not follow automatically from the applicable national corporate and property laws. However, in practice the aggregate impact of the multiple layers of contractual terms on which intermediary services are provided throughout the custody chain can result in end investors having much less control over the exercise of shareholder rights than a direct, non-intermediated investor would have.Footnote 35 Buried in the small print may be terms that relieve or limit intermediaries’ responsibilities with respect to the exercise of voting rights by end investors.Footnote 36 In addition, little-noticed terms of service that permit intermediaries to lend shares may mean that end investors have lost control rights at the relevant time.Footnote 37 The problems are compounded in the (common) case of international chains due to cross-border variation in both national company laws and the terms on which intermediary services are provided.Footnote 38 In practice, it is asset managers and proxy advisers that typically play a key role in the exercise of control rights.Footnote 39

Corporate governance-related problems with custody chains exist in major markets around the world.Footnote 40 This article’s focus on the situation in Europe, by which is meant the EU/EEA and also the UK, is timely for a number of reasons. First, equity investors in European companies often have no practical alternative to being part of a custody chain because of the way that trading, clearing and settlement are organized. The holding of securities in book entry form will be mandatory for EU/EEA issuers admitted to trading venues by no later than 2023 for new securities and 2025 for existing securities.Footnote 41 The UK is now on a different path as regards shares that are still held in paper form but the practical impact of this particular consequence of Brexit is limited because the majority of publicly traded UK equities are already held in dematerialized form in CREST, the national CSD.Footnote 42

Secondly, the development of a deeper equity culture is a key part of the flagship Capital Markets Union (CMU) project, first launched by the European Commission in 2015 and now in its second five-year plan.Footnote 43 CMU is all about removing barriers to the free movement of capital across the single market. The vital role that custody chains play in enabling investors to invest internationally has been mentioned already in this article. That there were significant barriers to cross-border investment associated with post-trade legal requirements and industry practices and processes was first put on the EU policy radar in the early 2000sFootnote 44 but it is the Shareholder Rights Directive, first adopted in 2007 and amended in 2017 (now SRD II), that most directly addresses the intersection of custody changes and corporate governance. SRD II, which, as noted earlier, also addresses the stewardship responsibilities of the investment industry through a suite of new transparency obligations on institutional investors, asset managers and proxy advisers, was operative before the end of the Brexit transition and therefore has been implemented in the UK.

The effective go-live date for the SRD II changes relating to custody chains was September 2020. Industry preparations for SRD II, which Broadridge, the US proxy voting and corporate communications services provider, described as ‘the most significant initiative for advancing European corporate governance for many years’,Footnote 45 are receiving their first real-life tests. This article is therefore among the first to have the benefit of evidence from practical experience to help assess the impact of the requirements.

4 SRD II and Custody Chains – The New Requirements

The following table provides a selective summary of the SRD II requirements relating to custody chains.Footnote 46 In addition to the Directive itself, an implementing act lays down supporting minimum requirements for standardized formats, types of information and data elements.Footnote 47 The use of common formats and message structures is intended to enable efficient and reliable processing and interoperability between intermediaries, companies and shareholders.Footnote 48 Standardization extends to prescribing the form and content of notices convening general meetings.Footnote 49 The implementing act also sets deadlines to help ensure the swift processing of transmissions and establishes procedures relating to ensuring the integrity and security of custody chain processes.Footnote 50 Deadlines depend on the matter in question but in many cases transmission on the same business day is required. The development of harmonized market standards and the use of modern communication technologies to promote further standardization over and above the prescribed requirements is expressly encouraged.Footnote 51

SRD II Chapter Ia: provisions with general application | |

|---|---|

In-scope companies (COs) (Art. 1(1)) | Registered office in EEA/UK and shares admitted to trading on EEA/UK regulated market. |

In-scope securities (Art. 1(1)) | Voting shares in in-scope companies. |

In-scope intermediaries (Art. 1(5)) | • Providers of safekeeping, administration or maintenance of securities accounts services (Art. 2(d)) in so far as ○ they provide services with respect to in-scope securities to shareholders (SHs) or other intermediaries. • Third-country intermediaries included. |

Non-discrimination, proportionality and transparency of costs (Art. 3d) | • Intermediaries to disclose publicly applicable charges for custody chain services, separately for each service. • Charges levied on COs, SHs and other intermediaries to be non-discriminatory and proportionate to actual costs incurred for delivering such services. • National laws may prohibit intermediaries from charging fees for services. |

SRD II Chapter Ia: specific requirements | |

|---|---|

Shareholder identification (Art. 3a) | • Right for CO to request SH identification from intermediaries (national laws may set minimum % level, not exceeding 0.5%). • Intermediary to communicate to CO without delay requested information re SH identity. • Where multiple intermediaries, CO requests are to be transmitted along chain without delay; information from intermediaries to be transmitted directly to CO/its nominee. • CO can obtain information re SH identity directly from any intermediary in chain that holds the information. • National laws may permit CSDs/other intermediaries or service providers to collect information re SHs and to transmit that information to COs. • Standardization of minimum requirements re format of requests and information transmitted. |

Intermediary to transmit information ‘without delay’ (Art. 3b) | • CO→SH/nominee: intermediary to transmit company information re exercise of rights flowing from shares (except where CO sends that information directly to SHs/nominees). • SH→CO: intermediary to transmit, in accordance with SHs’ instructions, information received from SHs re exercise of rights flowing from their shares. • Multiple intermediaries in chain: intermediaries to transmit information along the chain (unless it can be directly transmitted to CO or SH/nominee). • Standardization of types and formats of information, including security and interoperability. |

Intermediary to facilitate exercise of SH rights, including right to participate and vote in general meetings (Art. 3c) | • Facilitation to be by one of ○ making arrangements for SH/nominee to be able to exercise rights themselves; or ○ exercising rights flowing from the shares upon explicit authorization and instruction of SH and for SH’s benefit. • Electronic confirmation of receipt of votes cast electronically to be sent to person that cast the vote. • SHs/nominees can obtain, at least upon request, confirmation that their votes have been validly recorded and counted. • Confirmations of votes cast sent to intermediaries must be transmitted to SH/nominee without delay either through the intermediary chain or directly. • Standardization of formats of confirmations, including security and interoperability. |

In terms of a high-level overview, the SRD II vision is of a single common interface for corporate actions, general meetings and shareholder identification that operates seamlessly across Europe. This vision responds to calls to streamline and simplify shareholder participation and identification stretching back over many years.Footnote 52 To achieve this, there is a need for detailed standardization at the operational level relating to message formatting, communication methods, technical interfaces and so forth. SRD II and the implementing act sensibly recognize that much of this technical work is best left to the market.

Market work on removing the so-called Giovannini barriers to efficient and effective cross-border clearing and settlement has been ongoing since the mid 2000s. The SRD II implementing act acknowledges that existing voluntary market standards for corporate actions processing were for the most part already applied, and that it was unnecessary therefore to specify more than key elements and principles with respect to those processes.Footnote 53 Market-led progress with respect to standardization of general meeting and voting practices had been less successful, however.Footnote 54 SRD II therefore has more heavy lifting to do in this area.

The most innovative element of the SRD II changes is the introduction of a harmonized mechanism for shareholder identification. Shareholder identification mechanisms already existed in around half of the EEA jurisdictions’ national laws but these were not necessarily designed with cross-border investors in mind, supporting processes were not standardized, shareholder opt-outs were possible in some jurisdictions, and cross-border application of sanctions against intermediaries (especially third-country intermediaries) was patchy.Footnote 55 Shareholder identification therefore represents the area where there are the most challenges – but also opportunities – for the market to provide new standards and systems to meet SRD II compliance requirements.

SRD II is not just about standardizing backroom processes and systems, however. An important advance achieved by SRD II is that it dismantles legal barriers to the cross-border disclosure of shareholder information. However, in the area of harmonization of key concepts on which the smooth and predictable operation of processes and systems depends, it is already clear that SRD II does not go far enough. Of the elements of unharmonized national company laws that continue to act as barriers to a seamless cross-border operation of processes relating to general meetings and shareholder identification, none is thornier than the thicket of possible responses to the seemingly simple question: ‘Who is my shareholder?’

4.1 Who Is the SRD II ‘Shareholder’?

The EU’s vision for a Capital Markets Union is maturing but its plans continue to have to skirt around some areas of law that are deeply embedded in national systems and on which there is resistance to harmonization. Aspects of company law and property law are in this category. In 2001, the influential Giovannini Report on cross-border clearing and settlement in the EU acknowledged that shares were creations of national legislative regimes and could never completely escape from them, that laws about what securities are and how they may be owned were a basic and intimate part of national legal systems, and that such systems were path-dependent and reflected the local socio-economic culture.Footnote 56 That fundamental differences in concepts underlying national laws would be difficult to remove was anticipated.Footnote 57 This observation was prescient so far as SRD II is concerned.

The drive towards greater consistency in the operation of custody chains has not yet touched continuing differences in national company laws on whether voting and economic rights are attributed to the first or final layers of holders in a custody chain.Footnote 58 In other words, whether the ‘shareholder’, as the person entitled as a matter of company law to assert voting and economic rights directly against the company, means the person at the first layer or at the final layer. The divergence in company laws is closely related to the national legal rules on proprietary interests. In some jurisdictions (such as France), the form for the holding of publicly traded securities is one in which the end investor is regarded as the owner of the securities and the role of the intermediaries in the chain is largely administrative.Footnote 59 There is also variation within this model, particularly as to whether as a default position the end investor is anonymous vis-à-vis the issuing company (which is the case in France).Footnote 60 In other jurisdictions, the predominant form is one whereby legal ownership and the direct relationship with the company is at the top of the custody chain and the end investor has only an indirect legal interest that either draws on generic legal concepts such as trusts and equitable interests (as in the UK and Ireland) or is a bespoke securities interest.Footnote 61 In others (such as Belgium and Germany), a co-ownership model as between intermediaries and the end investor is involved.Footnote 62 Moreover, national laws may allow for different answers depending on whether bearer or registered shares are involved.Footnote 63

In not attempting to harmonize the definition of shareholder, SRD II has left a troubling gap that undermines the aim of the reforms related to custody chains.Footnote 64 The Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) has described the continued existence of 27 different definitions of a shareholder across the bloc as ‘a significant challenge’ for the development of the consistent market standards that are needed to support the operationalization of the new measures on custody chains.Footnote 65 In an earlier report, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) had anticipated that problems would arise from the lack of agreement on who the law recognizes as a shareholder.Footnote 66 In 2020, the European Commission’s High-Level Forum on the Capital Markets Union called for a harmonized definition of ‘shareholder’ in SRD II as part of a package of measures to foster greater investor engagement and cross-border investment.Footnote 67 The new European Commission Capital Markets Union (CMU) action plan picks up this recommendation as a key action.Footnote 68

Consider the implications: if there is uncertainty about whose identity – shareholder or end investor – matters for SRD II purposes, then intermediaries risk contractual and/or legal, regulatory or administrative liability for disclosing sensitive information if they identify the ‘wrong’ person;Footnote 69 corporate information may not reach the ‘right’ person at the right time; and votes may be cast wrongly. In effect, improvements at the level of market standards, systems and processes are compromised because more fundamental matters remain uncertain.

4.2 Who Is the ‘End Investor’?

Before proceeding to look at how the shareholder/end investor problem is playing out in practice, it is necessary to detour briefly to establish what is meant by the term ‘end investor’. This term is not used in SRD II or the implementing act. This article therefore follows market standards in using the term to mean an investor that acquires and holds shares via a custody chain as distinct from an end saver that buys units in pooled funds that then are invested in equities or other securities.Footnote 70 While end savers are similar to end investors in having an economic interest in the performance of the equities in which their savings end up, their position is nevertheless distinguishable from that of end investors who for technical or efficiency-related reasons route their investment in equities through a custody chain. The end saver in a fund or other collective product is not setting out to invest directly in equities and has no reasonable expectation of getting direct control of the bundle of rights generally associated with being a shareholder. The end saver holds a different type of financial instrument.

The popularity of active and passive funds, pensions, life insurance and other pooled products as the preferred destination for long-term retail savings means that the typical end investor at the end of a custody chain will be an asset manager, pension fund trustee or other institutional investor that itself is subject to an array of investment management duties owed to its end savers. However, it remains possible for the end investor in a custody chain to be a retail or other small direct participant in the capital markets. As noted in an earlier section of this paper, there are signs of a (modest) upturn in direct retail investment in equities in some markets. There is debate about the desirability in principle of retail investor participation in corporate governance, given that retail investors are, it is argued, likely to be relatively uninformed and inexpert compared to those in the investment industry.Footnote 71 While it is not the purpose here to explore fully the policy issues associated with uninformed voting, this article aligns with others that have not found the risk of uninformed voting to be convincing justification for features of custody chains that legally or practically deprive end investors (retail or, indeed, institutional) of the power to control the exercise of voting or other shareholder rights.Footnote 72 Market structures that have developed through ‘haphazard happenstance and necessity’Footnote 73 and that reflect incumbencies and inequalities of bargaining power do not necessarily align with the set of efficient arrangements that are most conducive to improving corporate governance for the benefit of society overall.

Are holders of depository receipts (DRs) (or even convertible bonds linked to voting shares) to be regarded as end investors? Functionally, since depository receipts are just a convenient mechanism for investors to invest globally in equities, from a corporate governance perspective that is focused on ensuring that control of shareholder rights is located with the person with the appropriate incentives, it could be argued that they should be within the scope of a purposive interpretation of shareholder for SRD II (or alternatively that a DR is a share for this purpose). On the other hand, a depository receipt is a different security from a share and it could be argued that it stretches the concept of shareholder too far to include DR holders. The relationship between the investor, the depository bank and the custodian in the issuer’s home country is not the standard custody relationship around which SRD II is designed. On this issue, market standards envisage the chain going only as far as the intermediary of the depository bank where the underlying shares are heldFootnote 74 but Member States have taken different views on the treatment of depository receipts (and convertible bonds) in their implementation of SRD II.Footnote 75

Both the preceding and following section of this article explain why the SRD II definition of shareholder requires further clarification. The takeaway from this section is the supplementary point that such reform will need to be comprehensive to prevent similar uncertainties and inconsistences to those around ‘who is my shareholder?’ persisting at the level of ‘who is my end investor?’.

4.3 SRD II: Illustrating the Limited/Troubled Application Where the Shareholder Is Not the End Investor

We return now to the problematic application of SRD II in circumstances where, as a matter of national company law, the shareholder is not the end investor. A paper published by the Association of Global Custodians - European Focus Committee (AGC-EFC) in August 2020 revealed a disturbingly chaotic picture at the national level on this point: some Member States’ company laws take a different position on whether the shareholder and end investor are one and the same depending on whether the shares are held in registered or bearer form; some Member States define the shareholder as the person at the top of the chain in their company laws but in the implementation of SRD II have sought to take a purposive approach that extends the scope to the end investor, which may not be legally defensible; in implementing SRD II some have gone down to the level of the end investor for the purposes of the shareholder identification right but not necessarily for other SRD II custody chain requirements, an approach which again is of doubtful legal validity.Footnote 76 SRD II thus struggles on two levels: it has created new uncertainties within national legal systems; and it has manifestly failed to achieve cross-border harmonization on a pivotal concept.

The cleanest approach from a national legal certainty perspective is simply not to go beyond the top layer where that person is identified as the shareholder as a matter of company law. The UK exemplifies this approach. But while this approach avoids creating uncertainty within national law, it does not align with the harmonizing spirit of SRD II.

The UK is a registered shares jurisdiction. The register, which for dematerialized shares held through CREST is maintained by Euroclear UK and International (EUI), records legal ownershipFootnote 77 and is prima facie evidence of matters required to be recorded.Footnote 78 The inclusion on the register of details of underlying beneficial interests is not permitted.Footnote 79 The identity of the end investor (also described as the beneficial owner) is not generally known to the issuing company and it is only the person named on the register (the ‘member’) that is formally entitled to raise shareholder rights against the company. In implementing SRD II, the UK proceeded on the basis that the SRD II shareholder identification and custody chain changes were largely irrelevant because, the UK being a ‘name on register’ jurisdiction, companies already knew the identity of their (registered) shareholders and communications with shareholders took place directly. This approach is supported by a recital in the amending Directive that is consolidated as SRD II, which states expressly that the Directive ‘does not affect the beneficial owners or other persons who are not shareholders under the applicable national law’.Footnote 80 But it is a surprising outcome when set against the general purpose of SRD II to improve the operation of custody chains, and the approach of the implementing act. As such, it has attracted criticism.Footnote 81

It is not that the UK is diametrically opposed to the principle of companies being able to identify their end investors, the transmission of information up and down custody chains and/or the facilitation of end investor control over the exercise of shareholder rights. Notwithstanding the firm adherence to the ‘name on register’ system and the fierce defence of it by market practitioners who view it as being critical to the delivery of the legal certainty on which the capital markets depend, the UK has in fact already recognized the need to go behind the register in certain circumstances. Since even before SRD II (though partly under the influence of earlier EU law) company law in the UK has contained a number of provisions that are designed to enable companies to identify end investors (beneficial owners) and also to foster communication and engagement between companies and end investors. Public companies can inquire into the identity of their end investors through the use of statutory powers to extract information from persons whom the company knows or has reasonable cause to believe to be interested in its shares.Footnote 82 It is permissible for a company to include a provision in its articles enabling a registered shareholder to nominate another person to exercise shareholder rights.Footnote 83 A registered shareholder may also nominate other persons to enjoy corporate information rights.Footnote 84 A registered shareholder that holds shares on behalf of others can exercise voting rights attached to different shares in different ways.Footnote 85 The casting of votes on shares held in a nominee account in accordance with the wishes of the end investors can be facilitated by the nominee-registered shareholder appointing those end investors as its multiple proxies.Footnote 86 It is even permissible for end investors to count towards the minimum number/percentage of registered shareholders required for certain members’ requests.Footnote 87

There are mixed views on how well these various provisions work in practice.Footnote 88 Hence the disappointment in some quarters that SRD II implementation was not used as the opportunity to put in place a stronger system for end investors to have their say in corporate governance. The point is also made that it is likely that market participants that are active in multiple markets will still want to align UK practices with those mandated by SRD II given the significant investment in the development of systems to support the SRD II requirements and the inefficiencies of maintaining idiosyncratic local market practices.Footnote 89 However, the possibilities for convergence at the level of market standards, systems and processes are bounded by the national legal requirements, and thus the retention, at least to some extent, of parallel processes may be unavoidable.

Ireland, on the other hand, exemplifies the legal uncertainties that arise from adopting a more purposive approach to SRD II implementation. Ireland, which is also a registered shares jurisdiction, has run into some difficulties by implementing SRD II in a way that seeks to cater for both ‘name on register’ shareholders and end investors. The term ‘shareholder’ does not have a single statutory definition in Irish company law and the regulations implementing SRD II refer equally to the end investor and the registered holder.Footnote 90 Practitioners report that this has led to market uncertainty about exactly who in the custody chain is within the scope of the new requirements.Footnote 91 The implications of such uncertainty are significant. The Association of Global Custodian-European Focus Committee notes that end investors would, in the end, be reliant on the Irish courts to protect them on the basis of a purposive interpretation of the term ‘shareholder’.Footnote 92 This unsatisfactory position is inimical to legal and commercial certainty. Euroclear Bank, which is the post-Brexit CSD for the Irish equities market, has adopted the ‘name on register’ approach in determining the ‘shareholder’ for SRD II purposes.Footnote 93

4.4 The Significance of the New Right for Companies to Identify Their Shareholders

It is one thing to know your shareholder but not your end investor (where different), it is another not even to know your shareholder. Whereas the former problem is an unintended (but not wholly unforeseen) consequence of not addressing a delicate company/property law matter, the latter problem is the one that the SRD II shareholder identification right was always meant to tackle. Recognizing that shareholder anonymity vis-à-vis the company is the common default position across swathes of the European capital markets, especially those jurisdictions where shares continue to be held mainly in bearer form, is thus key to appreciating the significance of the SRD II shareholder identification mechanism.

A 2016 study by the European Central Securities Depositories Association (ECSDA) found that registration with respect to shares held in CSDs was mandatory in roughly half of the 38 European markets surveyed.Footnote 94 Countries in the mandatory group included the UK, Ireland, Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway, and such bearer shares as did exist in these countries were effectively a legacy effect and represented only a small proportion of the markets. The states where registration was still optional included Germany, France and Luxembourg, and in these markets, bearer shares continued to be widely used, at the level of 50-75 per cent, or even up to 100 per cent, of shares held within CSDs. (Note that while the term ‘bearer’ shares has connotations of physical certificates of ownership, it continues to be used in the dematerialized securities world to describe shares whose owners’ names are not recorded in an official register.)

France exemplifies the standard default position with respect to dematerialized bearer shares in which companies do not know who their shareholders and end investors (if different) are. As an illustration, Air France-KLM explains how the French dematerialized bearer share system works as follows:

In France and the Netherlands, holding shares in bearer form is the most common method: the purchase and day-to-day management is entrusted to the financial intermediary chosen by the shareholder. This method of holding shares enables the different shares in a portfolio to be regrouped with a single intermediary. The financial intermediary alone knows the identity of the shareholder.Footnote 95

Other French companies’ websites provide similar explanations.Footnote 96

Bearer shares whose holders are not known to the issuing company are also common, for example, in Germany. Market sentiment is that SRD II will have a massive impact on most German public companies.Footnote 97

Before SRD II, French law already provided a mechanism (titre au porteur identifiable (TPI)) whereby companies could discover the identities of shareholders. There were also shareholder identification procedures under German domestic law. The TPI procedure was introduced into French law in 1987 but through to 2019 (when the SRD II changes took effect), it could be used only if this was provided for in the articles of association.Footnote 98 The TPI system was further refined in 2001 to facilitate its use with respect to third-country intermediaries holding securities for clients resident outside France (providing a kind of template for SRD II’s treatment of third-country intermediaries). Overall, this system was successful but it was considered to be expensive for issuers so they did not use it very often, and usually only ahead of a general meeting (especially if contentious).

Unsurprisingly, as well as changing the law, SRD II has galvanized market developments aimed at providing technologies to simplify shareholder identification processes and ensure SRD II compliance throughout the chain.Footnote 99 Service enhancements developed in response to the revised regulatory environment are expected to enable shareholder identification with more transparency and lower cost than legacy procedures.Footnote 100 Unfortunately, it appears that some legacy national systems remain in operation in parallel to those adopted for the purposes of SRD II compliance.Footnote 101 The retention of parallel systems is not conducive to the achievement of the aim of a single common interface.

4.5 Operational Challenges and Opportunities

The operational challenges and opportunities arising from SRD II come into focus at this point.

In 2017, ESMA presented a general assessment of the level of harmonization of national regulatory frameworks for shareholder identification and communication across the EEA.Footnote 102 Its findings indicated low levels of harmonization in many operational areas: top-down corporate communication processes through chains of intermediaries were diverse and based either on national practices or on legal frameworks; standard forms and formats for bottom-up communication between issuers and shareholders were available in several jurisdictions but with non-harmonized contents, and intermediaries seemed to play a limited role in many areas. The ESMA survey fed into the SRD II implementing act (SRD II IR) and provides useful background context against which to consider its operational impact.

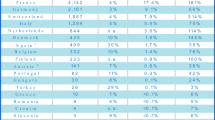

In short, meeting the SRD II IR requirements for information to be in electronic and machine-readable format using internationally applied industry standards (i.e., ISO 20022) has required a quite significant technology infrastructure upgrade. This has not been without glitches.Footnote 103 There have been reports of technological problems due to internal systems not being ready in time for new standardized electronic messaging formats,Footnote 104 and of interim solutions having to be deployed.Footnote 105 In its December 2021 Report, the ECB’s Advisory Group on Market Infrastructures for Securities and Collateral (AMI-SeCo), which has responsibility for compliance monitoring against the market standards, reported challenges in respect of cross-border activity owing to differences in the definition of shareholder and operational procedures (among other matters), problems related to some intermediaries not being able to process information in the correct electronic format, difficulties in verifying that shareholder identification requests were really coming from or on behalf of issuers because not all parties in the chain were in contractual relationships with each other, and issues related to the continued use of paper-based requests.Footnote 106 AMI-SeCo actually found a dip in compliance with the market standards on corporate actions, notwithstanding that this was already the most mature area pre-SRD II, but acknowledged that this could have been related to enhanced rigour in the monitoring process, adjustments to the assessment methodology and the introduction of a new facility for non-domestic markets to report non-compliance cases for the first time. In total, out of 40 markets, six were found to be fully compliant with the market corporate actions standards, 15 with the T2S corporate actions standards and six with the shareholder identification standards

On the more positive side, it can also be observed that SRD II is driving technological innovation and creating new business opportunities for both incumbents and new entrants. For instance, the (I)CSD group Euroclear launched a new InvestorInsight service aimed specifically at supporting intermediaries in meeting their SRD II obligations.Footnote 107 The other major European (I)CSD group Clearstream saw the transition to ISO 20022 as an opportunity to encourage its clients to sign up to the enhanced proxy voting service provided by ISS, its sister company.Footnote 108 Upcoming regulatory changes (i.e., SRD II) played a part in positioning Proxymity, an investor communications and proxy voting services start-up initially sponsored by Citi, to attract some of the world’s largest financial institutions to invest in the platform and establish the company as an independent business.Footnote 109 Broadridge identified itself as having played a key role in helping tier-one custodians, banks and brokers comply with SRD II requirements, noted ‘unprecedented’ demand for its solutions, stressed its ability to provide same-day responses, and highlighted the capacity of its platform to leverage advanced application programming interface (API)- and blockchain-based technologies for timely, secure and compliant response to shareholder disclosure requests.Footnote 110 BNY Mellon, the largest global custodian, was among those that worked with Broadridge to enhance the proxy voting services offered to clients in response to SRD II changes.Footnote 111 Other examples of innovation could be given but this small sample can suffice to give a flavour of the market response to SRD II as both a challenge and an opportunity.

This prompts the question: ‘Is technology today – or in the very near future – poised to solve the barriers to effective shareholder/end investor engagement created by custody chains?’ But before turning to that topic, this section concludes with a brief discussion of two remaining issues that have surfaced as points of concern in the first phase of SRD II implementation.

4.6 Corporate Governance Implications of Giving Companies the Right to Know Their Shareholders Earlier

While it is the case that SRD II formally provides that shareholder personal data can only be processed so as to identify shareholders in order, in turn, to communicate directly with a view to facilitating the exercise of shareholder rights and shareholder engagement with the company,Footnote 112 disentangling mixed purposes on the part of companies requesting shareholder identification would likely to be difficult if not downright impossible.Footnote 113 Companies do not need to give reasons for triggering shareholder identification under SRD II, and a ‘real’ purpose of using it as a tool simply to make an early discovery of who is investing in a company’s shares could be easily masked.

There is a rich academic and practitioner literature exploring whether the tactical building up of ‘hidden’ stakes by activist and other investors before they hit identification/disclosure thresholds is beneficial to corporate governance overall.Footnote 114 In that regard, it is notable that few Member States have taken advantage of the option to set a minimum shareholding threshold (not exceeding 0.5 per cent) on the right for companies to identify their shareholders.Footnote 115 This option was inserted into SRD II at a last stage in the legislative process and as a compromise between the interests of investors that would prefer to remain anonymous and the company’s interest in knowing who has invested in its shares. By not opting in, Member States have sent quite a strong signal as to the perceived public policy value of this compromise.

The impact on activism of the new SRD II shareholder identification right is somewhat attenuated by the fact that it enables the company, rather than the market as a whole, to identify shareholders. However, Member States could go further in the direction of market transparency in their national implementation: Italy exemplifies, although it is also worth noting that Italy is also one of the Member States that has opted into the 0.5 per cent threshold.Footnote 116 It has been argued that from a governance perspective the interaction of existing Italian laws and its implementation of the SRD shareholder identification right could create more problems than it solves.Footnote 117

4.7 Information Rights and Facilitated Exercise of Shareholder Rights – Are Opting-out and Outsourcing Still Allowed?

The European Commission’s conviction that the proposals eventually adopted in SRD II were needed was based on wide consultation across the sector that identified recurring problems that in general made the cross-border exercise of rights flowing from securities by investors both difficult and costly.Footnote 118 Contractual terms and practical realities of the way in which custody chains operate can sometimes confound the expectations of smaller and retail investors that want to have a say in the way that companies are run. While institutional investors are more adept at navigating these complexities, even they can encounter some difficulties.Footnote 119

Nevertheless, for many end investors the delegation of voting discretion to other finance professionals may represent the rational choice.Footnote 120 Many functions in the financial markets are outsourced to specialists, a practice which allows for a concentration of expertise, economies of scale and efficient management of cross-border diversified portfolios.Footnote 121 In some cases delegation may be a function of regulatory requirements that make managing investors for others a regulated activity requiring specific authorization.Footnote 122 The prevalence within custody chains of provisions that manage the allocation of corporate governance control rights through contract speaks powerfully to their value and popularity as an efficient and cost-effective way for end investors, including institutional investors and small funds, to structure their investment activity.

The possibility of shareholders’ opting out from services designed for their benefit is not expressly excluded by SRD II and there is an in-passing reference to ‘unless otherwise agreed by the shareholder’ in one provision of the implementing act.Footnote 123 However, the position on this important point could be made clearer. In a future reform of SRD II, the ability of shareholders to waive rights that exist exclusively for their benefit should be put beyond doubt.

By the same token, shareholder opt-outs do not (and should not in future) extend to the new corporate rights with respect to shareholder identification: shareholders cannot block intermediaries from providing the required information if a company requests identification because this measure is not purely in its purpose.

The post-SRD II revised market standards for general meetings stress that opt-outs must be at the initiative of the investor, that intermediary opt-out is not permitted, and that investors must be able to make informed decisions based on clear explanations as to the default position being that they will be offered the services, the price of the services and the implications of opting out.Footnote 124 There is a general principle in the standards to the effect that cost should not influence the decision to opt out, but since the cost saving involved in opting out will likely always matter to investors, this principle is presumably intended to be related to the obligation on intermediaries to offer services at costs which are appropriate, proportionate and non-discriminatory.

It also remains possible for shareholders to appoint nominees to exercise their rights and/or for intermediaries to exercise these rights on their behalf provided the intermediaries do so upon express authorization and instruction of the shareholders and for the shareholders’ benefit.Footnote 125 The requirement for ‘express authorization and instruction’ may help to address the problem of wording that limits an investor’s control being buried in the contractual small print.

5 Will Technology Eliminate Custody Chains? Not Quite Yet …

The Giovannini Group’s forward-looking assessment in the early 2000s was that the removal of barriers to efficient cross-border clearing and settlement would continue to be best achieved through a combination of private sector initiative and public sector intervention. That insight remains as convincing today as it was twenty years ago.

There is intense market, regulatory and academic interest in the potentiality of digital technologies to transform post-trade processes.Footnote 126 The use of new technologies in the areas of shareholder identification, corporate actions and general meetings is already growing.Footnote 127 APIs – interfaces that enable interaction, access and data exchange between different software systems – are especially apt for the purpose of facilitating easier information flows up and down custody chains. As noted earlier, Broadridge has made much of its API capabilities in the context of its SRD II services. Alongside this, distributed ledger technology (DLT) – in simplest terms, a tamperproof record-keeping service that anyone can accessFootnote 128 – has an obvious potential application in the modernization of the way in which corporate registers and other records are maintained and shared. Models for DLT-based utility-type services for a decentralized directory of information to identify end investors and for electronic voting are already in development.Footnote 129

The more profoundly transformative potential of digital technologies in the world of post-trade is also starting to take shape. The outline of a future world in which technology has eliminated custody chains by establishing a different norm whereby securities are held and settled in the names of end investors can be discerned. The Swiss Stock Exchange Group (SIX) is playing a pioneering role in this respect with the first tokenized bond issuance using DLT technology on its new SIX Digital Exchange in September 2021 and strong predictions of more to follow at pace.Footnote 130 However, there are many factors that explain why ‘grand visions of disintermediation or total digital transformation at scale are still far from being realized’.Footnote 131 Significant restructuring is required and business cases for this are uncertain.Footnote 132 Delivery versus payment settlement design in the DLT environment, including the need (or not (i.e., if settlement is instantaneous)) for liquidity provision and access to central bank money, is currently underexplored.Footnote 133 Regulatory choices regarding which barriers to remove and what restrictions to impose in order to ensure a safe and efficient digital environment that does not create new prudential and/or conduct risks and maintains regulatory neutrality between different types of provider are another attention point.Footnote 134 The potential extension of the settlement finality protection afforded to established payment systems and securities settlement systems is an important legal topic.Footnote 135 Interoperability both between legacy and new DLT systems and between DLT systems is another key concern.Footnote 136 So, too, is DLT governance.Footnote 137 EU and UK bodies clearly recognize that facilitating greater use of digital technologies and ensuring their resilience and safety are two sides of the same public policy coin.Footnote 138

Besides, as discussed earlier, settlement services are typically just one part of a range of asset servicing and collateral management services offered by financial market infrastructures and their custodian/intermediary participants. This whole ecosystem needs to be redesigned to ensure that the rich diversity of investor services and economies of scale for all parties are not compromised by the adoption of new technology. There is also the consideration that investor preferences for direct recording in the names of end investors in place of the established arrangements are largely untested (some may prefer a default position of being anonymous vis-à-vis the company, even if that is subject to the company’s right to seek identification). Moreover, there are also broader issues at stake with respect to new digital technologies, such as whether they are truly tamperproof, their propensity to be used for criminal activity, and their implications for privacy and data protection.Footnote 139 Finally, but most certainly not least among the challenges involved, there is the prospect of multi-jurisdictional legal upheaval associated with the transition from a world of traditional financial instruments held in dematerialized electronic form to native digital assets.

All of which points more towards a process of incremental change rather than sudden transformation. A period of step-by-step transition during which new tools and actors compete with tried, tested and trusted existing business models and incumbents is to be expected.Footnote 140 This period is likely to be characterized by experimentation facilitated, where necessary, by ‘regulatory sandbox-style’ exemptions from normal regulatory requirements.Footnote 141 Some envisage this transition period lasting up to 30 years,Footnote 142 although such a long timeframe feels extremely cautious given the pace at which breakthroughs are being announced.Footnote 143 Not all of the touted benefits will actually materialize – some will likely prove to be hype.Footnote 144

The conclusion that the custody chain as we know it today is therefore not about to disappear makes the need to address the shortcomings of SRD II an all the more urgent policy priority. There is the prospect of a virtuous circle whereby reform of SRD II both enables the exploitation of current technologies to their fullest extent and drives further market innovation.

The standout issue for the EU legislative bodies is to resolve the uncertainty about who is meant by the ‘shareholder’ in SRD II. This, of course, needs to be tackled in a way that does not endanger the legal certainty with respect to proprietary and security interests that underpins market systems that, on a daily basis, safely process an eye-wateringly large volume and number of transactions.Footnote 145 The review of this issue also needs to be mindful that change will cut both ways: improving the efficiency of end investor participation in corporate governance, but at the same time also providing what in practice is a new tool for the de-anonymization of the end investor vis-à-vis the company. The distinction between the end investor and end saver, and the position for SRD II purposes of holders of depository receipts and convertible bond holders are other matters that should also be clarified when the opportunity arises.

There are other aspects of the legal and regulatory framework around shareholder voting and corporate actions that would also benefit from further harmonization to complement technological developments and support the further evolution of standardized market practices.Footnote 146 The original version of what is now SRD II made a start with respect to harmonizing the arrangements for general meetings of shareholders, but significant differences in practice remain. Record dates is one topic that comes up frequently as a candidate for further harmonization, and it is on the European Commission’s radar.Footnote 147 While there is already a harmonized requirement for companies to set record dates,Footnote 148 there is a certain amount of divergence between Member States in the calculation of the date, resulting in what ESMA has described as only ‘a medium level of convergence’.Footnote 149 A process that allows the determination of voting entitlements to be carried out with certainty and pan-European consistency is essential if the goal of ensuring that shareholder engagement is not distorted by procedural/technical issues is to be achieved. Moreover, in some countries, shareholders still have to lodge a paper power of attorney as part of the general meeting remote voting process and/or companies are obliged/permitted to communicate with their shareholders via a range of channels including traditional post.Footnote 150 Legacy requirements such as these are clearly in need of modernization.

A good case for further harmonization can also be made with respect to the option to impose a threshold on companies’ right to identify shareholders. Member State interest in taking up this option has been quite limited and removing this option would lead to a cost saving for those firms operating in multiple markets that have had to adapt their systems to accommodate local thresholds. It would mean some erosion of shareholder privacy but modestly extending the rights of companies to identify their shareholders seems unlikely to entail significant corporate governance downsides.

A shareholder rights regulation rather than another directive would promote more consistent implementation and application on the ground.Footnote 151 However, when what became SRD II was proposed in 2014, the Commission noted that ‘only some basic principles’ regarding shareholder identification, transmission of information and facilitation of the exercise of rights could be achieved because of the need to align with distinct corporate governance frameworks.Footnote 152 National systems of corporate law and governance have not dramatically converged in the intervening years. This makes SRD III, perhaps as a ‘maximum harmonization’ directive coupled with another implementing act that aims to prevent diverging implementation at the detailed level, the more likely form of the next reform package, with the possibility of a regulation left for some future date.

6 Conclusion

Shareholder engagement has come to be seen to be pivotal to good corporate governance. From that starting proposition it follows that it is more important than ever to consider whether the mechanisms of shareholder engagement are up to the task they are meant to perform. Historically, these mechanisms have fallen short. Custody chains perform valuable functions but they also create a distance between the company and the end investor from which flows a significant risk of voting preferences and other important information not passing smoothly up and down the chain. Corporate governance is thus at risk of being distorted by process deficiencies. The other side of the corporate governance coin is that custody chains can help to keep the identity of end investors hidden from companies. This can work to the advantage of activist investors but whether it is conducive to good corporate governance that serves the interests of society is debatable.

The Shareholder Rights Directive II (SRD II) is an important intervention by the EU to tackle the corporate governance shortcomings of custody chains. One year on from these SRD II changes being transposed into national laws and becoming operative in practice (including in the UK, albeit only to a very limited extent), this article has found a mixed picture. The post-trade industry has taken the opportunity to upgrade shareholder identification, voting and related services offered to clients, the transition to fully electronic, latest market standards communications is underway, and there have been technological innovations. But experience has also shown that SRD II has not fully delivered on the necessary degree of harmonization, especially with respect to who is the ‘shareholder’ for this purpose. Shares are creations of national company and property laws and there are differences across EU/UK national legal regimes as to where control of shareholder rights sits within a custody chain. This has created problems for the application of SRD II in practice. SRD II has therefore struggled on two levels: it has created new uncertainties within national legal systems; and it has manifestly failed to achieve cross-border harmonization on a pivotal concept.

SRD II is based on improving custody chains rather than eliminating them. At a time of great excitement about the potential of new technologies, it is tempting to look to digital solutions that could eventually do away with custody chains and their associated problems for the operation of corporate governance. But custody chains are part of a complex post-trade ecosystem and they do provide significant benefits as well as some downsides. The digital transformation of an ecosystem – especially one whose very purpose is to take risk out of the financial system – is a mammoth undertaking. Technical complexities, uncertain business cases for ditching costly legacy systems and moving to costly new technologies, policymakers and regulators’ intense focus on ensuring that the facilitation of innovation does not come at a cost of insufficient safeguards against risky practices that threaten public welfare, potentially huge changes to securities, company and property laws across multiple jurisdictions, and differing investors’ preferences with respect to loss of anonymity are among the factors that will dictate the pace of the digital (r)evolution. A more gradual pace of change will likely involve new technologies being embraced first to improve the functioning of the existing system, including custody chains. Blockchain and API interfaces are already being offered by leading providers to help intermediaries meet their existing SRD II compliance obligations and there are also important public sector/central bank-led initiatives in this field.

Ruling out the possibility that profound technological change will eliminate custody chains in the short term makes addressing the shortcomings of SRD II an all the more pressing policy issue for the EU/EEA. The UK now has the regulatory autonomy to adopt solutions that are tailored for its domestic situation, but internationally active intermediaries, for which idiosyncratic local practices represent operational burdens, can be expected to urge UK policymakers to keep a close eye on the trajectory of EU law on these matters and to resist unnecessary divergence.

Notes

Financial Conduct Authority (2019), para. 5.16.

Dimson et al. (2015).

Hirschman (1970).

Becht et al. (2019).

On the differences between active and index (passive) fund models: Bebchuk et al. (2017), pp 94-95.

Broyer and Doyle (2020).

Financial Conduct Authority (2019), para. 5.5.

Dunne (2020).

Kastiel and Yaron (2016).

The 2018 data for the UK showed the proportions of UK shares beneficially owned by UK-resident individuals rising to 13.5%, up by 1.2 percentage points from 2016, moving further away from the historical low of 10.2% in 2008. However, the more recent 2020 data showed a fall to 12%: Office for National Statistics (2022).

Better Finance, a body that advocates for the interests of European savers and investors, argues that the decline over decades in the number of individual shareholders and their share of EU listed companies is linked to EU policies not being favourable overall to the development of individual share ownership. EU policy emphasis remains mostly on promoting retail participation in the capital markets via pooled products: European Commission (2021a).

32% compared to 80% according to a recent study of US retail shareholder voting behaviour: Brav et al. (2021).

Ibid.

European Commission (2020a), p 13.

See generally: https://www.sayonclimate.org/ (accessed 24 March 2022).

Daniels (2018), p 439 (discussing the future emergence of decentralized autonomous organizations for shareholder voting).

Directive 2017/828 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 amending Directive 2007/36 as regards the encouragement of long-term shareholder engagement [2017] OJ L 132/1, Arts. 3g-3k. This article uses SRD II to refer to the consolidated revised version of the Directive.

Regulation (EU) 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment [2020] OJ L198/13 (EU Taxonomy Regulation); Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability‐related disclosures in the financial services sector [2019] OJ L317/1 (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)). The EU Taxonomy Regulation and SFDR were not operative in the UK at the end of the Brexit transition period and were therefore not required to be onshored. The UK is developing its own green taxonomy and disclosure requirements based on adoption of the Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer et al. (2021). In 2021, the EU introduced a package of measures requiring different types of investment fund manager to integrate sustainability risks into the factors to be taken into account as part of their duties towards investors: European Commission (2021b). This package stopped short of explaining whether investors had duties to consider undertaking stewardship activities, but in a new strategy document published a few months later the European Commission acknowledged the need to do more to clarify the fiduciary duties and stewardship rules of investors to reflect the financial sector’s contribution to green deal targets: European Commission (2021c).

Katelouzou and Puchniak (2022).

See the database maintained by the European Corporate Governance Institute: https://ecgi.global/content/codes-stewardship (accessed 24 March 2022).

Katelouzou and Puchniak (2022).

Ibid.

E.g., Euroclear Finland, Euroclear Sweden and Euroclear UK & International (which operates the CREST system) offer this option: https://www.euroclear.com/services/en/private-investor-services.html (accessed 24 March 2022).

Twemlow (2019).

Fisch (2017).

Law Commission (2020), ch. 3.

Some jurisdictions (notably the US) prohibit or significantly restrict discretionary voting by brokers on behalf of end investors.

Hirst and Robertson (2021); Law Commission (2014), paras. 11.86-11.88. The EU Securities Financing Transactions Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2015/2365 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on transparency of securities financing transactions [2015] OJ L333/1, (onshored in the UK by the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 (but with certain changes made by statutory instrument)) imposes new disclosure and reporting requirements on fund managers with respect to their use of securities funding transactions to assist investors to understand the risks and returns and make better informed investment choices.

What is permissible contractually will always depend on the applicable broader legal framework. Regulatory requirements may require that particular investment products guarantee a right to vote to the end investor: e.g., the UK Individual Savings Account Regulations 1998, SI 1998/1870 exemplify.

Kay (2012), para. 3.13.

Regulation (EU) No 909/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on improving securities settlement in the European Union and on central securities depositories and amending Directives 98/26/EC and 2014/65/EU and Regulation (EU) No 236/2012 [2014] OJ L257/1 (CSDR), Art. 3. The recording of securities in book-entry form can take place outside a CSD: CSDR, rec. 11. ‘Dematerialized form’ means that financial instruments exist only as book entry records: CSDR, Art. 2.1(4).

CSDR continues to apply in the UK as retained EU law but only in respect of provisions that were operative immediately before exit day, which excludes the dematerialization requirement as it does not apply until 2023 at the earliest: European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020, s 3; the Central Securities Depositories (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2018, SI 2018/1320. Independently of EU law, the UK has instigated its own full dematerialization project for publicly traded shares not held in CREST, but at the time of writing it is unclear how vigorously it is being pursued.

Broadridge (2020).

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1212 of 3 September 2018 laying down minimum requirements implementing the provisions of Directive 2007/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards shareholder identification, the transmission of information and the facilitation of the exercise of shareholders rights [2018] OJ L223/1 (SRD II IR).

SRD II IR, rec. 2.

SRD II IR, Annex, Table 3.

SRD II IR, Arts. 9-10.

SRD II IR, rec. 11.

European Securities and Markets Authority (2017), para. 45.

Ibid., paras. 11-23.

Giovannini Group (2001), pp 54-55.

Ibid., p 60; Art. L228-1 French Code de commerce.

European Securities and Markets Authority (2017), Annex 1, paras. 47-50.

Dixon (2019).

Ibid. The company could force registered shares: Art. L228-1 Code de commerce; it does not happen in practice for listed issuers

Dixon (2019).

Ibid.

Association of Global Custodians - European Focus Committee (2020).

SRD II, Art. 2b refers the definition of shareholder back to national laws.

Association for Financial Markets in Europe (2020).

European Securities and Markets Authority (2017), paras. 13-14.

High-Level Forum on the Capital Markets Union (2020), p 16.

European Commission (2020a), Action 12.

SRD II, Art. 3a(6) requires Member States to ensure that intermediaries that disclose shareholder identity information are not considered to be in breach of any restriction on disclosure imposed by contract or by any legislative regulatory or administrative provision, but only where they do so in accordance with the rules laid down in this Article [emphasis added].

Fisch (2017).

Daniels (2018), p 406.

Association for Financial Markets in Europe et al. (2020).

Association of Global Custodians - European Focus Committee (2020).

Ibid.

The Uncertificated Securities Regulations 2001, SI 2001/3755 (USR), reg. 20.