Abstract

There are common aspects in the corporate law of the most important economies, such as free transferability of shares, legal personality, and limited liability. Those aspects, however, develop in different ways and at different speeds in each country, as they are a product of local economic and regulatory influence. The foremost example is the well-known distinction between countries where dispersed ownership prevails and those where defined control is more commonly found. Despite the existence of differences, there seems to be a convergence throughout the world. Historically, Brazil has been part of the concentrated control group, but it is also participating in the convergence process. For example, public corporations with dispersed ownership and attempted hostile takeovers are emerging in Brazil. This article aims to analyse whether there are certain important conditions in the Brazilian reality for a convergence towards an environment of dispersed ownership. Thus, this study, which does not pretend to be exhaustive, seeks to analyse the following existing issues: (1) reduction of private benefits of control; (2) protection against creeping acquisitions; (3) conflicts of interest; (4) voting; and (5) liability of the controlling shareholder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kraakman et al. (2004), at p 1.

Bebchuck and Roe (2004), at p 69.

La Porta et al. (1998).

Ibid.

Kraakman et al. (2004), at p 1.

Coffee Jr (2001), at p 1.

Relatório Oficial sobre Governança Corporativa na América Latina (2003), at p 54.

Oioli (2008), at p 37.

According to Lipton and Steinberger (1976), at pp 1–10.4, ‘[a] takeover is an attempt by a bidder (“raider”) to acquire control of a subject company (“target”) through direct acquisition of some or all of its outstanding shares. Most commonly, takeover bids are made directly to shareholders of the target as a cash tender offer or as an exchange offer of raider securities for target stock. The principal takeover approaches include a “friendly” transaction negotiated with management; a “bear hug”, in which the raider notifies the target of a proposed acquisition transaction; a “hostile” offer made directly to target shareholders, without management approval; and, as a supplement or alternative to these approaches, large open market and/or privately negotiated purchases of target stock’. (emphasis added)

Coffee Jr (2001).

Oioli (2008), at p 38.

According to Oioli (2008), at p 38, ‘in spite of the attempts at legislation, the first signs of capital dispersal in Brazil seem to be the result of the self-regulation introduced by the BOVESPA Novo Mercado. The Novo Mercado is a listing segment intended for trading shares issued by companies that undertake, voluntarily, to adopt additional corporate government practices beyond those required by law. This is an attempt to create new corporate regulations by contractual means. Once they sign up, companies automatically become subject to the Novo Mercado regulations.’

Bebchuck (1999), at pp 29–46. Some empirical data indicate that, in concentrated markets, initial public offerings (IPOs) rarely involve more than a minority of voting capital, with the controlling shareholder retaining a controlling stake for future private negotiations with third parties who may be interested in acquiring it. See Holmen and Högfeldt (2004).

Under Brazilian law, an obvious benefit is the recognition of the premium for control provided by Article 254-A of Law No. 6404/76.

The Novo Mercado regulations state: ‘3.1 Authorisation for Trading in the Novo Mercado. The Managing Director of BOVESPA may authorise a company to be traded on the Novo Mercado if it meets the following minimum conditions:… (vi) its capital stock is represented exclusively by common shares, except in cases of privatisation, where there are preferred shares of a special class intended to ensure differentiated political rights, and that are non-transferable and belong to the privatising entity, in which case such rights must be analysed in advance by BOVESPA’. (emphasis added)

‘Article 15. The shares, according to the nature of the rights that they confer on their holders, are common, preferred or fruition shares…. § 2o The number of preferred shares with no voting rights, or restricted voting rights, may not exceed fifty percent (50%) of the total number of shares issued.’ (emphasis added)

Article 254 of Law No. 6404/76 (repealed by Law No. 9457 of 5 May 1997) was worded as follows: ‘Art. 254. Disposal of control of a public company shall be subject to the prior approval of the Brazilian Securities Commission. § 1 The Brazilian Securities Commission must ensure that minority shareholders are accorded equal treatment through a simultaneous public offer for the acquisition of shares.’

Carvalhosa and Eizirik (2002), at p 385.

Ibid., at p 386.

Prado (2005), at pp 92–96.

Partially, because Article 254-A specifies payment to voting minorities of only 80% of the price paid for voting shares of the controlling stake. The law thus accepts that (i) a premium should be paid to controlling shareholders, and (ii) there is no need to protect holders of non-voting shares, who may also be considered as minority shareholders.

The fact that the Novo Mercado, as we have seen above, does not allow preferred shares to be issued eliminates the discriminatory treatment of minority shareholders with or without voting rights which was created by Article 254-A.

The Novo Mercado regulations read as follows: ‘8.1 Agreement for Disposal of Control of the Company. Disposal of control of the Company, whether in a single or in successive transactions, shall be agreed under the suspensive or resolutory condition that the acquirer undertakes to make a public offer for the acquisition of the remaining shares from the other shareholders of the Company, subject to the conditions and periods set forth in the current legislation and in these Regulations, so as to ensure them equal treatment to that accorded to the Controlling Shareholder who is disposing of shares.’

The Novo Mercado regulations read as follows: ‘4.3 Composition. The board of directors shall consist of at least five (5) members, elected by the general meeting, of which a minimum of twenty percent (20%) shall be Independent Directors.’

The definition provided in the Novo Mercado regulations is as follows: An ‘Independent Director’ is one who: ‘(i) has no ties to the Company, other than an equity interest; (ii) is not a Controlling Shareholder, spouse or close family member (to the second degree) of a Controlling Shareholder, and neither has, nor has had in the three (3) previous years, any ties to any company or entity related to a Controlling Shareholder (excluding persons with ties to public education or government research entities); (iii) in the three (3) previous years has not been an employee or officer of the Company, or of the Controlling Shareholder or of a subsidiary of the Company; (iv) is not a direct or indirect provider, supplier or buyer of goods and/or services, to an extent that would imply loss of independence; (v) is not an employee or senior manager of any company or entity that is offering or requesting services and/or products to and from the Company to an extent that would imply loss of independence; (vi) is not a spouse or close family member (to the second degree) of any senior manager of the Company; and (vii) is not entitled to any payment by the Company other than the consideration earned as director (excluding cash distributions received in the capacity of an equity holder).’

Oioli (2008), at p 176.

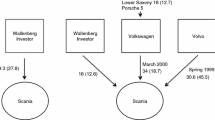

According to Roberta Nioac Prado, ‘a creeping acquisition through the Stock Exchange is a mechanism for acquiring control of a company consisting in the gradual acquisition, on a Stock Exchange (Secondary Market) and, possibly, through private deals with minority shareholders, of voting shares issued by a target public company by a person, or group of persons, whether individual or corporate, until a sufficient number of voting shares are acquired to effectively exercise control over this public company’. In Prado (2005), at p 70.

According to Oioli (2008), at p 37, ‘accumulation through a stock market is a way of acquiring share control by the successive purchase on the stock market of small lots of shares in circulation, until the purchaser attains a percentage of the voting capital of the company that gives control. It is possible also for this objective to be attained by a strategy of private acquisitions, entering into agreements directly with minority shareholders.’

Ibid., at pp 46–47.

Ibid., at p 47.

Ibid., at p 48.

The Novo Mercado regulations provide the following: ‘8.2 Acquisition of Control by Means of Successive Acquisitions. A person who holds shares in the Company and acquires Control thereof, by means of a private agreement for share purchases entered into with the Controlling Shareholder, involving any number of shares, shall be required to: (i) make the public offer referred to in 8.1; and (ii) reimburse the shareholders from whom shares have been purchased on a stock exchange during the six (6) months preceding the date of Transfer of Control, by paying the difference between the price paid to the Controlling Shareholder disposing of control and the amount paid on the stock exchange during this period, duly adjusted’. (emphasis added)

Oioli (2008), at p 47.

França (1993), at n 128.

Leães and de Barros (1989), at p 25.

See, for instance, RT 615/162 and TJSP, 11.18.1996, in Eizirik (1998), at p 175.

The positioning of case law is fully backed by doctrine, as Jaeger (2000) rightly points out. Jaeger holds that the delegation of such a decision to a judge prejudices the autonomy of the company, added to the fact that the judge is not sufficiently trained in technical matters to venture into the field of company business. See also França (1993), at p 46.

da Cunha (2007) developed an in-depth study on this matter.

Salomão Filho (2002), at pp 28–29.

This concept comes from Jaeger himself, revisiting corporate interests 40 years on, see Jaeger (2000).

Hansmann and Kraakman (2001), at n 89.

França (1993), at p 22.

It should be noted that the purpose of this study is not to make the economic analysis of the law a matter of values, but to use it as an exclusively analytical tool.

Hansmann (1996), at p 18.

Salomão Filho (2002), at p 42.

According to the theory of the ‘organisation contract’, we should no longer distinguish between the two concepts on the basis of whether or not a common purpose exists, as in the classical teaching of Ascarelli (1945). This theory holds that the differentiation should be made on the basis of the nucleus of contracts. While the nucleus of contracts of association is in the organisation created (coordination of reciprocal influence between acts), in contracts for exchange the fundamental purpose is the attribution of subjective rights. Thus, if the theory of the organisation contract is upheld, it is in the value of the organisation, rather than in the coincidence of interests of a number of parties, or in a specific desire for self-preservation, that the defining element of the corporate contract can be seen (Salomão Filho 2002, at pp 42–43).

Salomão Filho (1995), at pp 57–61.

Ibid., at p 73.

Ribeiro (2009), at p 25.

According to Eisenberg (2006), at p 98, ‘[i]t is well known that proxy voting has become the dominant mode of shareholder decision-making in publicly held corporations’. Easterbrook and Fischel (1996), at pp 64–65, similarly, affirm that ‘[t]here are nonetheless recognizable patterns in corporate choice under these states…. Shareholders vote by proxy, not in person, and elect the slate of candidates proposed by incumbents’. These authors reinforce the idea that proxy voting is the pressing question and that it should be properly regulated, so that the capital market can develop along the lines of a mass shareholding system.

Ribeiro (2009), at p 59.

Ibid., at p 60.

To be fulfilled by a mandatory bid, as required by Article 254-A of Law No. 6404/76.

References

Ascarelli T (1945) Problemas das Sociedades Anônimas e Direito Comparado, 2nd edn. Saraiva, São Paulo

Bebchuck, LA (1999) A rent protection theory of corporate ownership and control. NBER Working Paper No. 7203

Bebchuck LA, Roe MJ (2004) A theory of path dependence in corporate governance and ownership. In: Gordon J, Roe MJ (eds) Convergence and persistence in corporate governance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Carvalhosa M, Eizirik N (2002) A nova Lei das S/A. Saraiva, São Paulo

Coffee Jr JC (2001) The rise of dispersed ownership: the role of law in the separation of ownership and control. Working Paper No. 182. http://papers.ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=254097. Accessed 18 Oct 2009

da Cunha RFP (2007) As Estruturas de Interesse nas Sociedades Anônimas. Quartier Latin, São Paulo

Easterbrook FH, Fischel DR (1996) The economic structure of corporate law. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Eisenberg MA (2006) The structure of the corporation. Beard Books, Washington DC

Eizirik N (1998) Sociedades Anônimas – Jurisprudência. Renovar, Rio de Janeiro

França E Valladão Azevedo e Novaes (1993) Conflito de Interesses nas Assembléias de S.A. Malheiros Editores São Paulo

Hansmann H (1996) The ownership of enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hansmann H, Kraakman R (2001) The end of history of corporate law. Georget Law J 89:439

Holmen M, Högfeldt P (2004) A law and finance analysis of initial public offerings. J Finance Intermed 13:324–358

Jaeger PG (2000) Interesse sociale rivisitato (quarent’anni doppo). Giurisprudenza Commerciale, pp 795–812

Kraakman R, Davies P, Hansmann H, Hertig G, Hopt KJ, Kanda H, Rock EB (2004) The anatomy of corporate law – a comparative and functional approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford

La Porta R, Lopez de Silanes F, Schleifer A (1998) Corporate ownership around the world. Harvard Institute of Economic Research Paper No. 1840. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=103130. Accessed 18 Oct 2009

Leães LG, de Barros Paes (1989) Estudos e Pareceres sobre Sociedade Anônima. RT, São Paulo

Lipton M, Steinberger EH (1976) Takeovers and freezeouts. Law Journal Press, New York

Oioli EF (2008) Oferta Pública de Aquisição de Controle de Companhias Abertas. Master’s Thesis

Prado RN (2005) Oferta Pública de Ações Obrigatória nas S.A. – Tag Along. Quartier Latin, São Paulo

Relatório Oficial sobre Governança Corporativa na América Latina (2003). http://www.oecd.org/daf/corporate-affairs/. Accessed 18 Oct 2009

Ribeiro RV (2009) O Direito de Voto nas Sociedades Anônimas. Quartier Latin, São Paulo

Salomão Filho C (1995) A Sociedade Unipessoal. Malheiros Editores, São Paulo

Salomão Filho C (2002) O Novo Direito Societário, 2nd edn. Malheiros Editores, São Paulo

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Godke Veiga, M., Oioli, E.F. Convergence and Divergence in Capital Market Systems: The Case of Brazil. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 18, 351–365 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-017-0073-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-017-0073-3