Abstract

Background

Japanese traditional (Kampo) medicines containing ephedra may be used to treat colds during pregnancy. There are reports that ephedrine, a component of ephedra, has a risk of teratogenicity; however, the evidence remains equivocal.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the risk of major congenital malformations (MCMs) associated with exposure to Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester of pregnancy using the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study (TMM BirThree Cohort Study).

Methods

To 23,730 mother–infant pairs who participated in the TMM BirThree Cohort Study from July 2013 to March 2017, questionnaires in early and middle pregnancy were distributed approximately at weeks 12 and 26 of pregnancy, respectively. Infants' risk of MCMs in women who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra or acetaminophen during the first trimester was assessed, and the odds ratios (ORs) were estimated with unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Results

Among 20,879 women, acetaminophen and Kampo medicines containing ephedra were used in 665 (3.19%) and 376 (1.80%) women, respectively, in the first trimester. Among the infants born to the mothers who used acetaminophen or Kampo medicine containing ephedra during the first trimester, 11 (1.65%) and 8 (2.13%), respectively, had overall MCMs. OR of overall MCMs was higher in women who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra than in those who used acetaminophen in the first trimester (adjusted OR, 1.45; 95% confidence interval (CIs), 0.57–3.71); however, the difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusions

In this study, there was no statistically significant association between the use of Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of MCMs. Although some point estimates of ORs exceeded 1.00, the absolute magnitude of any increased risks would be low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This is the first study to evaluate the risk of major congenital malformations (MCMs) associated with exposure to Japanese traditional (Kampo) medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester of pregnancy in Japan. |

We found no increased risk of MCMs in pregnant women exposed to Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester. |

1 Introduction

Herbal medicines are used worldwide to treat various conditions during pregnancy [1,2,3]. Their usage is up to 60% in developed countries is primarily because of the perception that herbs are natural and do not pose adverse effects, unlike conventional medicines [1, 4]. Traditional Japanese (Kampo) medicine originates from traditional Chinese medicine, and it is widely used together with modern medicine in clinical settings, including in obstetrics [5,6,7,8]. In Japan, previous birth cohort studies using data from the Japan Environment and Children's Study showed that the percentages of pregnant women who had taken Kampo medicines during the period from the time of diagnosis up to 12 weeks of pregnancy and after 12 weeks of pregnancy were 6.0% and 9.4%, respectively, and the percentages were high after the diagnosis of pregnancy. However, the term “Kampo medicines” previously indicated all types of preparations [9]. Another study using a large Japanese claims database showed that kakkonto and shoseiryuto, which contain ephedra and are used to treat the common cold, are prescribed most frequently during pregnancy [10].

Ephedra is a botanical herb used in traditional Chinese medicine and contains ephedrine and pseudoephedrine as the main alkaloids [11]. It acts as a stimulant of the central nervous system (CNS) and can induce other effects, including increased heart rate, vasoconstriction, and increased blood pressure [12]. Ephedra promotes perspiration, which impairs peripheral circulation and causes hemodynamic disturbances in the fetoplacental system [11, 12]. Several studies involving animals and humans have demonstrated the risk of malformation of vasoactive substances such as ephedrine during pregnancy [12,13,14,15]. However, these studies are limited by small sample sizes.

Because studies investigating the safety of medicines generally exclude pregnant women, safety information regarding Kampo medicines during pregnancy has not yet been obtained [4]. No comprehensive or detailed studies have been conducted on the use of Kampo or herbal medicines during pregnancy. To the best of our knowledge, information on the safety of Kampo medicines containing ephedra, which are used to treat the common cold during pregnancy, is lacking. Therefore, this study evaluated the risk of major congenital malformations (MCMs) associated with exposure to Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester of pregnancy. The study was based on data from the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study (TMM BirThree Cohort Study), which was a multigenerational genome and birth cohort study.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This study was based on data obtained from the TMM BirThree Cohort Study, a prospective cohort study conducted in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. Detailed information regarding the TMM BirThree Cohort Study has been provided elsewhere [16, 17]. Pregnant women and their family members were contacted in obstetric clinics or hospitals between 2013 and 2017, and 23,730 mother–infant pairs participated in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. All the participants were free to decline consent to participate in the study and were informed that there were no disadvantages or risks involved in their refusal to participate. The TMM BirThree Cohort Study protocol was approved by the Tohoku University and Internal Review Board of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (2013-1-103-1).

2.2 Data Collection

2.2.1 Medication

All data on medication during early and middle pregnancy were obtained based on a questionnaire that was distributed at approximately weeks 12 and 26 of pregnancy, respectively. Most questionnaires were distributed and collected by trained genome medical research coordinators through face-to-face interviews with pregnant women at approximately 50 obstetric clinics and hospitals in Miyagi, which participated in the recruitment process [18]. The prevalence of using acetaminophen and Kampo medicines containing ephedra during pregnancy was evaluated. Next, data on medication from the time of pregnancy diagnosis to approximately week 12 of pregnancy were used to evaluate the risk of MCMs associated with exposure to Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester. The names of medicines self-reported by the participants were often ambiguous; therefore, determining the exact medications were difficult. Therefore, multiple pharmacists and one medical doctor matched self-reported names of medicines with generic names based on Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) medicus [19]. We defined Kampo medicines that contain ephedra and are used to treat common cold as follows: kakkonto (KEGG ID: D06698), kakkontokasenkyushin’i (D06928), shoseiryuto (D06987), maoto (D07042), and maobushisaishinto (D07043). In the 18th Japanese Pharmacopoeia, ephedra has been defined as the terrestrial stem of Ephedra sinica Stapf, Ephedra intermedia Schrenk et C.A. Meyer, or Ephedra equisetina Bunge (Ephedraceae). Ephedra contains ephedrine and pseudoephedrine as ≥ 0.7% of the total alkaloids, calculated on the basis of dried material [20].

2.2.2 Major Congenital Malformations (MCMs) Outcomes

The MCMs obtained from medical records at birth and in the first month of life are shown in Table 1. After consultation with a paediatrician, the patients were categorised according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), and MCMs were identified using algorithms established by the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort study group [21, 22]. The exclusion criteria included chromosomal anomalies and minor congenital malformations. We examined nine categories of congenital malformations related to CNS, eye, ear, face, upper limb, thorax, abdomen, urogenital system, back, and musculoskeletal system. A full list of the MCMs is provided in Table 1.

2.2.3 Covariates

Considering previous studies and the characteristics of the population in the present study, we included maternal age at delivery, pregnancy complications, infertility treatment, parity, use of suspected teratogenic medications, preterm birth, infant sex, alcohol use during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, and household income as covariates of MCM outcomes [23]. In the Guidelines for Obstetrical Practice in Japan, 2017 edition [24], the suspected teratogenic medications are listed as follows; in early pregnancy: etretinate, carbamazepine, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, danazol, hiamazole, trimethadione, valproate, vitamin A (retinol), phenytoin, phenobarbital, mycophenolate, misoprostol, methotrexate, and warfarin. Data on maternal age, infertility treatment, and parity were obtained from medical record at registration of this cohort study. Pregnancy complications were obtained from postpartum medical records. Gestational weeks and infant sex were obtained from medical records of newborns. We defined the pregnancy complications in this study as follow: threatened abortion, threatened premature delivery, fetal growth restriction, blood type incompatibility, gestational diabetes mellitus, premature rupture of the membranes, low lying placenta, deep vein thrombosis, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placental abruption, non-reassuring fetal status, iron deficiency anaemia, placenta previa, placenta accreta, uterine inversion, oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, amniotic fluid embolism, intrauterine infection, atonic bleeding, haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count syndrome, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, intrauterine fetal death, and obstetrical disseminated intravascular coagulation. Data on household income and alcohol consumption and smoking status during pregnancy were obtained using a self-report questionnaire.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Women who used acetaminophen in the first trimester were used as the reference group in all analyses. Measurements of specific infectious agents are difficult in observational studies, leaving an opportunity for uncontrolled confounding. To eliminate the possibility of confounding by infectious diseases and adjust for the same exposure conditions, women who used acetaminophen, which is used to treat the common cold and is considered safe during pregnancy [25], were considered as the reference group. The characteristics of mothers and infants were compared between two groups: pregnant women who used acetaminophen and those who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester. Continuous and categorical variables were described as mean (standard deviation), frequency or proportion. Differences in prevalence were analysed using the chi-squared test. We adjusted the propensity score for the use of Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester because we could not adopt propensity score matching or weighting owing to limited sample size and number of outcomes. The propensity scores were calculated using maternal age at delivery, pregnancy complications, infertility treatment, use of suspected teratogenic medications, delivery history, preterm delivery, smoking during pregnancy, alcohol use at pregnancy, body mass index before pregnancy, and annual household income in a logistic regression model. Logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association between the use of Kampo medicines containing ephedra in the first trimester and risk of developing MCMs. Odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A sensitivity analysis was conducted for MCMs. First, unadjusted and adjusted analyses were restricted to women who did not use suspected teratogenic medications in the first trimester. Second, the analyses were repeated for those who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra, including those who used them for illnesses other than the common cold in the first trimester. In addition to the five Kampo medicines containing ephedra, which are used to treat the common cold, we defined other Kampo medicines containing ephedra as eppikajutsuto (D06921), kakkontokajutsubuto (D06927), keishakuchimoto (D06951), keimakakuhanto (D06953), gokoto (D06955), goshakusan (D06956), shimpito (D06994), bofutsushosan (D07041), makyokansekito (D07044), makyoyokukanto (D07045), and yokuininto (D07048). These Kampo medicines are mainly used for asthma, obesity or oedema, but not the common cold [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Third, the analyses were repeated for those who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra, including those who used them for illness other than the common cold in the first trimester, with women who did not use any medicines in the first trimester as the reference group. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of the Participants

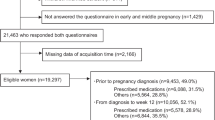

Of the 23,730 mother–infant pairs, 592 women withdrew informed consent, 628 had multiple births, 890 were participating for the second or third time in the survey, and 741 did not answer the questionnaire during early and middle pregnancy; these individuals were excluded from the study (Fig. 1). The numbers of women who used acetaminophen and Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester were 774 (3.71%) and 505 (2.42%), respectively. Shoseiryuto (n =260, 1.25%) was the most frequently used medicine during the first trimester, followed by kakkonto (n = 220, 1.05%) and kakkontokasenkyushin’i (n = 12, 0.06%) (Online Supplementary Material (OSM) Table 2). We excluded women who used both acetaminophen and kampo medicines containing ephedra in the first trimester, and analysed the data from 1,041 eligible mother–infant pairs, as shown in the flowchart of Fig. 1. Of these 1,041 women, 665 used acetaminophen, and 376 used Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester. Maternal and infant characteristics are shown in Table 2. Women who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester were older and less likely to have pregnancy complications than women who used acetaminophen.

3.2 Risk of MCMs Associated with Exposure to Kampo Medicine Containing Ephedra During the First Trimester

Of the 20,879 infants, 388 (1.86%) had MCMs. In this analysis, 11 of 665 (1.65%) infants born to mothers who received acetaminophen during the first trimester had overall MCMs. Furthermore, eight of 376 (2.13%) infants born to mothers who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester had overall MCMs (Table 3). Considering MCM within each category, the CNS exhibited the highest frequency, followed by the urogenital system, thorax and abdomen, in that order.

The OR of overall MCMs was higher in women who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra than that in women who used acetaminophen in the first trimester (crude OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.52–3.24; adjusted OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.57–3.71). Moreover, ORs of MCMs for the thorax (adjusted OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.21–7.99), abdomen (adjusted OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 0.29–16.10) and urogenital system (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.40–10.39) were relatively high in women who used Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester. However, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 4). The sensitivity analyses yielded results similar to those of the primary analysis (OSM Tables 3 and 4). The use of all Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester was not associated with a risk of MCMs in infants, compared with not taking any prescription or over-the-counter medication in the first trimester (crude OR, 1.11; 95% CI 0.55–2.27; adjusted OR, 1.13; 95% CI 0.55–2.31).

4 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the risk of MCMs associated with exposure to Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester in Japan. We did not find a statistically significant association between the use of Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester of pregnancy and risk of MCMs in infants. None of these results affected the conclusions of the sensitivity analyses.

The proportion of pregnant women who used acetaminophen changed slightly before and after diagnosing pregnancy. However, the proportion of pregnant women who used Kampo medicines, specifically shoseiryuto, which is used to treat the common cold, was higher during pregnancy than before pregnancy. Kampo medicines have been shown to be more acceptable to pregnant women [1, 34]. Kampo medicines for the common cold were used more frequently during pregnancy, which was consistent with the results of the prescription status of Kampo medicines during pregnancy in a Japanese claims database study [10]. The possible association between ephedra and an increased risk of birth defects in humans is worrisome because ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, which are the constituents of the ephedra extract in these Kampo medicines, have been linked to cardiac anomalies in animal teratology studies [13, 35]. However, the ephedrine doses used in these studies were substantially higher than the recommended doses for humans. Ephedra-containing weight-loss products have not been associated with heart defects, but they showed an increased OR for anencephaly and anorectal atresia [12]; however, these associations are not statistically significant for the ephedra-containing products. Our findings were consistent with the reports of previous studies, indicating that products containing ephedra do not pose a teratogenic risk, although the number of events were not so many as to test the association between ephedra and each MCM. Large cohorts with hundreds of thousands of pregnancy cases are necessary to estimate the risk of the most specific MCMs [35].

The use of single-component pseudoephedrine is not associated with an increased risk of gastroschisis or small intestinal atresia (SIA), whereas combination products containing both pseudoephedrine and acetaminophen are associated with a 4.2-fold increased risk of gastroschisis and threefold increased risk of SIA [14]. In most countries, Kampo medicines are available over the counter, making them highly accessible. Because patients might think that Kampo medicines are natural and free of any adverse effects, unlike conventional medicines, their use is not always reported to healthcare professionals [36]. Therefore, healthcare professionals must always ask pregnant women whether Kampo medicines or natural products are being used. In this study, information on over-the-counter Kampo medicines was collected through a questionnaire, which allowed us to determine the correct situation of medication among pregnant women.

This study had some limitations. First, the participants were limited to pregnant women who voluntarily participated in the TMM BirThree Cohort Study. Therefore, several cooperative and health-conscious pregnant women were more likely to have participated in the study. Second, the small number of events limited the statistical significance of this study. Therefore, further evidence on the teratogenic risk of Kampo medicines containing ephedra is necessary; however, the findings of this study may still assist in clinical decision-making. Third, there is still potential for misclassification or misinterpretation of medication use because of the self-reported questionnaires. However, this study included over-the-counter traditional Chinese medicines. This is a unique strength since such an analysis would not be feasible using only prescription databases. Fourth, retrospective questioning is prone to causing recall bias. However, our study may have a higher validity because pregnant women are generally more concerned about the use of medication than the general population. Fifth, we did not consider the frequency or quantity of medication use and it is possible that shyoseiryuto and maobushisaisinto may have been taken daily for allergic rhinitis. It was difficult to rule out the influence of the virus based on whether or not the subject was taking a particular drug, which introduced another bias. Sixth, some pregnant women who had miscarriages or stillbirths did not return the questionnaires or withdrew their consent. Therefore, medication use for women whose pregnancies ended in an abortion or stillbirth might not have been fully evaluated.

5 Conclusion

This study did not find a statistically significant association between the use of Kampo medicines containing ephedra during the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of MCMs. Although some point estimates of ORs exceeded 1.00, the absolute magnitude of any increased risks would be low. Therefore, this study may assist in clinical decision-making.

References

Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Choi S, Han D. Safety classification of herbal medicines used among pregnant women in Asian countries: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:489.

John LJ, Shantakumari N. Herbal medicines use during pregnancy: a review from the Middle East. Oman Med J. 2015;30(4):229–36.

Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, Nordeng H. Herbal medicine use in pregnancy: results of a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:355.

Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227–35.

Sugimine R, Kikukawa Y, Kurihara D, Arita R, Takayama S, Kikuchi A, Oshawa M, Ishii T. Kampo medicine prescriptions for hospitalized patients in Tohoku University Hospital. Trad Kampo Med. 2021;8:221–8.

Kita T, Sano T, Makimoto F, Isohama Y. Only Kampo medicine can cure these symptoms in the field of obstetrics and gynecology. In: 1st International Symposium on Kampo medicine. Trad Kampo Med. 2022;9:194–5.

Jing Y, Fukuzawa M, Sato Y, Kimura Y. Kampo medicine for women's health care. In: 1st International Symposium on Kampo Medicine. Trad Kampo Med. 2022;9:123–4.

Suzuki S, Obara T, Ishikawa T, Noda A, Matsuzaki F, Arita R, Oshawa M, Mano N, Kikuchi A, Takayama S, Ishii T. No association between major congenital malformations and exposure to Kampo medicines containing rhubarb rhizome: a Japanese database study. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1107494.

Nishigori H, Obara T, Nishigori T, Metoki H, Ishikuro M, Mizuno S, Sakurai K, Tatsuta N, Nishikima I, Fujiwara I, Arima T, Nakai K, Mano N, Kuriyama S, Yaegashi N, Japan Environment & Children’s Study Group. Drug use before and during pregnancy in Japan: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Pharmacy. 2017;5:21.

Suzuki S, Obara T, Ishikawa T, Noda A, Matsuzaki F, Arita R, Oshawa M, Mano N, Kikuchi A, Takayama S, Ishii T. Prescription of Kampo formulations for pre-natal and post-partum women in Japan: Data from an administrative health database. Front Nutr. 2021;8: 762895.

Zheng Q, Mu X, Pan S, Luan R, Zhao P. Ephedrae herba: a comprehensive review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;307: 116153.

Bitsko RH, Reefhuis J, Louik C, Werler M, Feldkamp ML, Waller DK, Frias J, Honein MA, National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Periconceptional use of weight loss products including ephedra and the association with birth defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82:553–62.

Nishikawa T, Bruyere HJ Jr, Takagi Y, Gilbert EF, Uno H. Cardiovascular teratogenicity of ephedrine in chick embryos. Toxicol Lett. 1985;29:59–63.

Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Maternal medication use and risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:26–31.

Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Hayes C, Mitchell AA, Mulliken JB. Vasoactive exposures, vascular events, and hemifacial microsomia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:389–95.

Kuriyama S, Yaegashi N, Nagami F, Arai T, Kawaguchi Y, Osumi N, Sakaida M, Suzuki Y, Nakayama K, Hashizume H, Tamiya G, Kawame H, Suzuki K, Hozawa A, Nakaya N, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Tsuji I, Fuse N, Kiyomoto H, Sugawara J, Tsuboi A, Egawa S, Ito K, Chida K, Ishii T, Tomita H, Taki Y, Minegishi N, Ishii N, Yasuda J, Igarashi K, Shimizu R, Nagasaki M, Koshiba S, Kinoshita K, Ogishima S, Takai-Igarashi T, Tominaga T, Tanabe O, Ohuchi N, Shimosegawa T, Kure S, Tanaka H, Ito S, Hitomi J, Tanno K, Nakamura M, Ogasawara K, Kobayashi S, Sakata K, Satoh M, Shimizu A, Sasaki M, Endo R, Sobue K, Yamamoto M, The Tohuku Medical Megabank Project Study Group. The Tohoku medical megabank project: design and Mission. J Epidemiol. 2016;26:493–511.

Kuriyama S, Metoki H, Kikuya M, Obara T, Ishikuro M, Yamanaka C, Nagai M, Matsubara H, Kobayashi T, Sugawara J, Tamiya G, Hozawa A, Nakaya N, Tsuchiya N, Nakamura T, Narita A, Kogure M, Hirata T, Tsuji I, Nagami F, Fuse N, Arai T, Kawaguchi Y, Higuchi S, Sakaida M, Suzuki Y, Osumi N, Nakayama K, Ito K, Egawa S, Chida K, Kodama E, Kiyomoto H, Ishii T, Tsuboi A, Tomita H, Taki Y, Kawame H, Suzuki K, Ishii N, Ogishima S, Mizuno S, Takai-Igarashi T, Minegishi N, Yasuda J, Igarashi K, Shimizu R, Nagasaki M, Tanabe O, Koshiba S, Hashizume H, Motohashi H, Tominaga T, Ito S, Tanno K, Sakata K, Shimizu A, Hitomi J, Sasaki M, Kinoshita K, Tanaka H, Kobayashi T, Kure S, Yaegashi N, Yamamoto M, Tohuku Medical Megabank Project Study Group. Cohort Profile: Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and ThreeGeneration Cohort Study (TMM BirThree Cohort Study): rationale, progress and perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:18–19m.

Sakurai-Yageta M, Kawame H, Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, Nakaya N, Nagami F, Minegishi N, Ogishima S, Takai-Igarashi T, Danjoh I, Obara T, Ishikuro M, Kobayashi T, Aizawa Y, Ishihara R, Yamamoto M, Suzuki Y. A training and education program for genome medical research coordinators in the genome cohort study of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:297.

Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D355–60.

The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. (2021) The Japanese Pharmacopoeia, 18th ed., English version. Available online at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11120000/000912390.pdf (Accessed May 24, 2023).

Blais L, Bérard A, Kettani FZ, Forget A. Validity of congenital malformation diagnostic codes recorded in Québec’s administrative databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:881–9.

Ishikawa T, Oyanagi G, Obara T, Noda A, Morishita K, Takagi S, Inoue R, Kawame H, Mano N. Validity of congenital malformation diagnoses in healthcare claims from a university hospital in Japan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:975–8.

Chuang CH, Doyle P, Wang JD, Chang PJ, Lai JN, Chen PC. Herbal medicines used during the first-trimester and major congenital malformations: an analysis of data from a pregnancy cohort study. Drug Saf. 2006;29:537–48.

Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan. 2017th ed. Tokyo: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology; 2017. (in Japanese).

Rebordosa C, Kogevinas M, Horváth-Puhó E, Norgard B, Morales M, Czeizel AE, Vilstrup H, Sorensen HT, Olsen J. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy: effects on risk for congenital abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(178):e1-7.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Bofutsushosan Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/062/pdf/062-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Eppikajutsuto Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/028/pdf/028-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Gokoto Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/095/pdf/095-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Shimpito Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/085/pdf/085-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Makyokansekito Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/055/pdf/055-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Yokuininto Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/052/pdf/052-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Goshakusan Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/063/pdf/063-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Kampo-Preparation TSUMURA Makyoyokukanto Extract Granules for Ethical Use. Available online at: https://medical.tsumura.co.jp/products/078/pdf/078-tenbun-e.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Hall HG, Griffiths DL, McKenna LG. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by pregnant women: a literature review. Midwifery. 2011;27:817–24.

Werler MM. Teratogen update: pseudoephedrine. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76:445–52.

Illamola SM, Amaeze OU, Krepkova LV, Birnbaum AK, Karanam A, Job KM, Bortnikova VV, Sherwin CMT, Enioutina EY. Use of herbal medicine by pregnant women: What physicians need to know. Front Pharmacol. 2020;10:1483.

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to all participants of the TMM BirThree Cohort Study and the staff members of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Tohoku University. A full list of members is available at https://www.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/english/a220901/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The TMM BirThree Cohort Study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (2013-1-103-1). Trained genome medical research coordinators were placed in each clinic, hospital, or community support centre to provide information on the TMM BirThree Cohort Study to potential participants and to receive signed informed consent forms from those who agreed to participate.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The data obtained through the TMM BirThree Cohort Study are incorporated into the TMM biobank. All data analysed during the present study are available for research purposes with the approval by the Sample and Data Access Committee of the Biobank.

Competing Interests

R.A., M.O., A.K., S.T. and T.I. belong to the Department of Kampo and Integrative Medicine, Tohoku University School of Medicine. The department received a grant from Tsumura & Co, a Japanese manufacturer of Kampo medicine; however, the grant was used according to Tohoku University guidelines. Potential conflicts of interest were addressed by the Tohoku University Benefit Reciprocity Committee and were managed appropriately. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Role of Funding Sources

The TMM BirThree Cohort Study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Japan [grant number, JP17km0105001, JP21tm0124005, JP21tm0424601]. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23K14378. Funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Authors’ Contributions

AN was responsible for conducting the study, data analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. TO and SKuriyama supervised the study. TO, FM, FU, KM and MI contributed to the interpretation of results and provided critical feedback. TO, FM, SS, RA, MO, FU, KM, MI, AK, ST, TI, HK, SKure and SKuriyama provided advice on critically essential intellectual content and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noda, A., Obara, T., Matsuzaki, F. et al. Risk of Major Congenital Malformations Associated with the Use of Japanese Traditional (Kampo) Medicine Containing Ephedra During the First Trimester of Pregnancy. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 11, 263–272 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00411-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00411-0