Abstract

Background

Rearrangements in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene define a molecular subgroup of non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) that should be treated with ALK-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

Objective

This study aimed to portray the Portuguese reality about the diagnosis and treatment of stage IV ALK-positive NSCLC.

Methods

Institutions that treat lung cancer in Portugal were invited to participate in an anonymous electronic questionnaire. A total of 22/35 geographically dispersed institutions responded. A descriptive statistical analysis of the results was performed.

Results

Reflex molecular testing was done in 54.6% of the institutions. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was the preferred diagnostic method (90.9%). Typically, physicians obtained molecular study results within 14–21 days. Alectinib was the most commonly used first-line treatment. For patients with brain metastases, 86.4% of the physicians preferred alectinib and 13.6% preferred first-line brigatinib. In the case of asymptomatic oligoprogression in the central nervous system, 85.7% of physicians performed local treatment and kept the patient on a TKI; if symptomatic, 66.7% gave local treatment and stayed with the TKI, while 28.6% gave local treatment and altered the TKI. For patients with symptomatic systemic progression, 47.6% and 38.1% of physicians prescribed lorlatinib after initial treatment with alectinib or brigatinib, respectively. After progression on lorlatinib, 42.9% of respondents chose chemotherapy and 57.1% requested detection of resistance mutations.

Conclusions

NGS is widely used for the molecular characterization of ALK-positive NSCLC in Portugal. The country has access to up-to-date therapy. Overall, national clinical practice follows international recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Next-generation sequencing was the main diagnostic technique of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with ALK rearrangement in Portugal. |

Among first-line ALK–tyrosine kinase inhibitors, alectinib was the most common; as second-line treatment, alectinib, brigatinib and lorlatinib were used. |

After progression on lorlatinib, most physicians requested detection of ALK-resistance mutations. |

1 Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, including in Portugal [1, 2]. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which comprises approximately 85% of lung carcinomas, is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage and has an unfavourable prognosis [3]. The discovery of driver gene mutations associated with specific subgroups of NSCLC has enabled the development of targeted therapies, resulting in improved clinical outcomes [4]. Rearrangements of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene define a molecular subgroup of NSCLC that are mainly lung adenocarcinomas, representing approximately 5% of NSCLC cases and characterized by sensitivity to ALK-directed tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [3, 5,6,7].

Crizotinib was the first TKI to demonstrate efficacy in the treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC. Compared with chemotherapy, crizotinib significantly improved progression-free survival and the objective response rate in patients with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC [8]. Even so, most patients progress on crizotinib, with a high rate of brain metastasis due to mechanisms involving the acquisition of ALK-resistance mutations, secondary activation pathways or poor penetration of the drug into the central nervous system (CNS) [9]. Later, the second-generation ALK–TKIs, ceritinib, alectinib and brigatinib were approved after demonstrating antitumour efficacy and intracranial activity in patients treated with crizotinib [10,11,12] and naive patients [13,14,15]. However, resistance to second-generation ALK–TKIs, with consequent progression, is well documented [16]. Lorlatinib is a third-generation ALK–TKI with high penetration into the CNS that covers a variety of ALK-resistance mutations [17]. It has demonstrated systemic and intracranial activity in advanced ALK-positive NSCLC, in patients previously treated with TKI and naive patients with or without brain metastases [18, 19]. Each new-generation ALK–TKI has specific potential adverse effects: diarrhea, nausea and emesis with ceritinib; constipation and myalgia with alectinib; early onset pneumonitis with brigatinib; and changes in lipid levels and cognitive and mood effects with lorlatinib [14, 15, 18,19,20,21,22].

In Portugal, as elsewhere in Europe, crizotinib [23, 24], ceritinib [25, 26], alectinib [27, 28], brigatinib [29, 30] and lorlatinib [31, 32] are approved for the treatment of advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. The selection and sequencing of new-generation ALK–TKIs is a challenge due to the lack of clinical trials that directly compare drugs. Further, there are no concrete data on the diagnosis and treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC at the national level. This study aimed to characterize Portuguese clinical practice in the diagnosis and treatment of stage IV ALK-positive NSCLC, as well as to frame the national experience within international recommendations, through the implementation of a questionnaire.

2 Methods

All the institutions that treat lung cancer in Portugal (n = 35), belonging to the National Health System or to the private sector, were invited by email to participate in an anonymous electronic questionnaire about the diagnosis and treatment of stage IV ALK-positive NSCLC. Between June 2022 and January 2023, 22 institutions responded using SurveyMonkey software. The physicians were asked to respond as representatives of the institution where they practice. This study did not include any intervention in human participants; therefore, institutional review board approval was not deemed necessary. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

The questionnaire, which was specifically developed by a panel of Portuguese experts from the Lung Cancer Study Group, consisted of 27 single-response questions organized by theme: sociodemographic characterization, diagnosis, first-line therapy, second-line therapy and subsequent therapies. A descriptive statistical analysis of the results was performed.

3 Results

3.1 Sociodemographic Characterization

A total of 22/35 institutions responded to the questionnaire (response rate: 63%). The sample included 16 pulmonologists and six oncologists from institutions in Lisbon and the Tagus Valley (40.9%), followed by the North (27.3%), Centre (13.6%), Alentejo (4.5%), Algarve (4.5%), Azores (4.5%) and Madeira (4.5%) (Tables 1 and S1). Most physicians worked in the public sector. Per week, 50.0% of physicians saw 21–40 lung cancer patients. Most respondents were currently treating fewer than ten patients with ALK-positive NSCLC.

3.2 Diagnosis

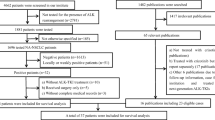

Figure 1 shows the diagnostic data of ALK-positive NSCLC in this study. In 72.7% of the centres, the anatomopathological study was performed at the institution (Fig. 1a). Molecular studies were performed at 36.4% of the centres (Fig. 1b). Molecular reflex testing was done in 54.6% of the centres.

Diagnosis of ALK-positive NSCLC in the studied institutions. a Place where the anatomopathological study was performed. b Place where the molecular study was performed. c Most frequently used detection method. d Mean wait time for the result of the molecular study. e Detection of ALK TKI resistance mutations. f Access to NGS of liquid biopsies. ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization, IHC immunohistochemistry, MS molecular study, NGS next-generation sequencing

The most frequent genetic detection method was next-generation sequencing (NGS; 90.9%) (Fig. 1c). Typically, physicians obtained the results of the molecular study within 14–21 days (72.7%); 18.2% of the institutions provided the results in less than 14 days and 9.1% in more than 21 days (Fig. 1d). Among the centres performing molecular reflex testing, 3/12 (25%) obtained the results in less than 14 days and 9/12 (75%) within 14–21 days; among the institutions performing upon request testing, 1/10 (10%) had the results in less than 14 days, 7/10 (70%) within 14–21 days and 2/10 (20%) in more than 21 days.

In most institutions, it was possible to request the detection of ALK-resistance mutations in cases of disease progression (Fig. 1e). However, 18.2% of the institutions did not have access to NGS of liquid biopsies (Fig. 1f). Additional data are given in Online Resource 1 (Table S2).

3.3 First-Line Therapy

Alectinib was the drug most frequently used in the first-line for ALK-positive NSCLC (Fig. S1a). In patients with brain metastases, 86.4% of the physicians more frequently chose alectinib and 13.6% chose brigatinib (Fig. S1b). Some 4.5% of the participants thought that the metastatic volume could determine the choice of chemotherapy as an alternative to TKI. For patients with performance status ≥ 2, 86.4% of physicians preferred alectinib and 13.6% preferred crizotinib (Fig. S1c). For patients aged ≥ 80 years, 86.4% of physicians preferred alectinib, 9.1% preferred crizotinib and 4.5% preferred brigatinib (Fig. S1d). Additional data are given in Online Resource 1 (Table S3).

3.4 Second-Line Therapy

Of the 22 institutions that responded to the questionnaire, 21 identified a second-line therapeutic strategy. In patients with extra-CNS oligoprogression, 95.2% of physicians performed local treatment and kept the patient on the same TKI, while 4.8% changed drugs without local treatment (Fig. S2a). In the case of asymptomatic oligoprogression in the CNS, 85.7% of physicians performed local treatment and stayed with the TKI, while 14.3% changed the drug without local treatment (Fig. S2b); if symptomatic, 66.7% of the respondents administered local treatment and kept the same TKI, 28.6% administered local treatment and altered the TKI and 4.8% changed the drug without local treatment (Fig. S2c).

In patients with asymptomatic systemic progression, 81.0% of respondents considered maintaining the drug in some cases and 19.0% always changed the drug (Fig. S2d). In patients with symptomatic systemic progression treated with first-line crizotinib, 80.0% of the physicians chose second-line alectinib and 20.0% chose second-line brigatinib. (Fig. S2e). In patients initially treated with alectinib, 52.4% of physicians requested detection of resistance mutations and 47.6% switched to lorlatinib (Fig. S2f). In patients initially treated with brigatinib, 61.9% of physicians requested detection of resistance mutations and 38.1% prescribed lorlatinib (Fig. S2g). Additional data are given in Online Resource 1 (Table S4).

3.5 Later Therapies

Of the 22 institutions that responded to the questionnaire, 21 identified a third-line therapeutic strategy (Table 1). After progression on lorlatinib, 57.1% of respondents requested detection of resistance mutations and 42.9% started chemotherapy. Thirty-three percent of the physicians reported that the detection of resistance mutations was useful in the next therapeutic decision, 47.6% did not consider it useful, 14.3% did not have access and 4.8% had access but did not request it. Most physicians did not consider immunotherapy in these patients. Additional data are given in Online Resource 1 (Table S5).

4 Discussion

ALK rearrangements should be investigated in patients diagnosed with advanced lung adenocarcinoma [33,34,35,36,37]. Our study revealed that in Portugal, NGS is the predominant diagnostic method in ALK-positive NSCLC, in line with international trends [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Several studies have shown a high level of agreement between NGS and fluorescence immunohistochemistry/in situ hybridization in the detection of ALK rearrangements [39,40,41, 45, 46], NGS being the most efficient diagnostic approach in NSCLC [38, 44].

Most institutions that responded to the questionnaire have access to NGS of liquid biopsies, in line with international practices. In fact, the diagnostic algorithm of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) for patients with advanced NSCLC who progress under TKI treatment advocates the detection of ALK-resistance mutations through NGS of liquid biopsy [47], as its efficacy has been demonstrated [48,49,50,51,52].

One of the main barriers to the implementation of personalized medicine in the treatment of advanced NSCLC is the delay in obtaining the results of molecular studies [53]. In the USA, the median time from diagnosis of advanced NSCLC to obtaining a positive result for ALK is 23–25 days [40, 44], but the IASLC/College of American Pathologists/Association for Molecular Pathology recommends that the waiting period not exceed 2 weeks [33]. In most Portuguese institutions, the results take 14–21 days, 1 week longer than international guidelines recommend. These data are in agreement with another Portuguese study of lung cancer, which reported a median waiting time for the results of biomarker assays of 17.9 days [54]. Lim et al. found that patients diagnosed with advanced NSCLC without a molecular study result at the first oncology visit experienced a delay of 13 days in the initiation of treatment compared with patients with available results at the time of the visit, underscoring the importance of early molecular diagnosis in advanced NSCLC [55]. A strategy to reduce the waiting time for molecular studies and thereby avoid delays in therapy is to do reflex testing of biomarkers, giving pathologists the autonomy to request the molecular study in the presence of a confirmed diagnosis of non-squamous NSCLC [56]. Our results suggest a trend for reflex testing to reduce the time needed to obtain the molecular study results versus upon-request testing, highlighting the relevance of reflex testing. In our study, only about half of the institutions performed reflex molecular testing, and those that took more than 21 days to obtain the result of the molecular study performed on request. Among the reasons why some institutions did not adopt reflex molecular testing may be to avoid the expense of mutation studies in patients in earlier stages, who were ineligible from the beginning for targeted therapies with TKI.

The present study reports a high nationwide use of alectinib in the first-line treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC, in line with the recommendations of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) [37]. In patients with brain metastases, most physicians chose first-line alectinib, while 13.6% preferred brigatinib. Both drugs are effective in this subpopulation of patients [15, 21]. In Portugal, public funding of brigatinib [29] occurred later than that of alectinib [27], which may explain the lower use of brigatinib in the first-line in this study.

The emergence of molecular resistance under therapeutic pressure from TKIs is a reality, and the sequential administration of ALK–TKIs until starting chemotherapy is a common treatment algorithm [57]. Debate remains about the therapeutic approach to oligoprogression in NSCLC: change the systemic therapy or continue with the current drug combined with local ablative treatment. Retrospective studies suggest that local treatment of all oligoprogressive lesions in NSCLC with driver mutations eradicates resistant subclones, prevents secondary dissemination and restores the sensitivity of metastatic sites to ongoing therapy [57]. Thus, local treatment would delay the change in therapy, prolonging the benefit of TKI and improving patient survival [57]. Although ESMO notes that the evidence supporting this recommendation is limited, its therapeutic algorithm for ALK-positive NSCLC advocates the administration of local treatment and the maintenance of systemic targeted therapy in the case of oligoprogression [37]. In Portuguese institutions, this was the preferred practice in patients with oligoprogression after first-line TKI.

Some 30–40% of patients with ALK-positive NSCLC have CNS metastases at diagnosis and 50–60% after treatment with crizotinib [58, 59]. Usually, brain metastasis is treated with radiotherapy, which can cause serious late adverse effects, potentially invalidating patients who survive a long time, such as patients treated with ALK–TKIs [59]. On the other hand, second- and third-generation ALK–TKIs have much greater penetration into the CNS than crizotinib [59]. Thus, it seems reasonable for asymptomatic patients to initiate treatment with specific inhibitors and undergo radiotherapy only after tumour progression or when symptoms appear [58,59,60,61]. This sequence provides the best quality of life for patients [59]. Our results revealed that for patients with asymptomatic oligoprogression in the CNS, most physicians administered local treatment and maintained TKI; only one-seventh of the respondents altered the TKI without applying local treatment. In symptomatic oligoprogression in the CNS, two-thirds of physicians administered local treatment and kept the same drug, while one-third administered local treatment and changed drugs.

In the systemic progression of ALK-positive NSCLC after first-line therapy with TKIs, ESMO recommends rebiopsy [37]. According to the algorithm, after first-line crizotinib, the choice is alectinib, ceritinib or brigatinib; after first-line treatment with another ALK–TKI besides crizotinib, lorlatinib is the option [37]. In our study, in patients with symptomatic systemic progression who were initially treated with crizotinib, the physicians administered second-line alectinib or brigatinib. In patients with symptomatic systemic progression treated with first-line alectinib or brigatinib, the majority of respondents requested detection of resistance mutations, which was in line with the ESMO recommendations [37]. Almost half of the physicians prescribed lorlatinib after initial treatment with alectinib, and approximately one-third administered lorlatinib after initial treatment with brigatinib.

Our data also revealed that after progression on lorlatinib, most physicians requested detection of resistance mutations and the other physicians administered chemotherapy. In these cases, the ESMO therapeutic algorithm recommends treatment with chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy [37]. The clinical utility of detecting ALK-resistance mutations after progression has been widely discussed. On the one hand, therapeutic sequencing with crizotinib, alectinib/ceritinib and lorlatinib covers the main mechanisms of ALK resistance [16]. On the other hand, a case of resensitization to crizotinib in a lorlatinib-resistant tumour via the ALK L1198F mutation was reported [62], suggesting the relevance of ALK mutation testing after progression under lorlatinib. In our survey, one-third of the physicians stated that the detection of resistance mutations was useful in their later therapeutic decisions. We do not know which mutations were found in the tumours observed by these physicians because the molecular detection panels detect different mutations.

The limitations of this study are the moderate adherence of the institutions invited to participate in the questionnaire, the fact that each institution was represented by one physician and the fact that studies based on questionnaires may exhibit response bias, including recall bias, which may influence the account of the facts [63]. However, in the absence of concrete data on the diagnosis and treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC in Portugal, our results allow us to draw a portrait of the management of these patients at the national level, providing a starting point for an in-depth discussion.

5 Conclusions

NGS is widely used for the molecular characterization of ALK-positive NSCLC in Portugal. The country has access to up-to-date therapy. Overall, national clinical practice follows international recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC.

References

The Global Cancer Observatory. Globocan—Portugal, https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/620-portugal-fact-sheets.pdf; 2020. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

The Global Cancer Observatory. Globocan—World, https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheets.pdf; 2020. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Cameron LB, Hitchen N, Chandran E, Morris T, Manser R, Solomon BJ, et al. Targeted therapy for advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;1(1):CD013453. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013453.pub2.

Hirsch FR, Suda K, Wiens J, Bunn PA Jr. New and emerging targeted treatments in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):1012–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31473-8.

Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05945.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2015.

Lin JJ, Riely GJ, Shaw AT. Targeting ALK: precision medicine takes on drug resistance. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(2):137–55. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1123.

Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2167–77. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1408440.

Zhang I, Zaorsky NG, Palmer JD, Mehra R, Lu B. Targeting brain metastases in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):e510–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00013-3.

Kim DW, Tiseo M, Ahn MJ, Reckamp KL, Hansen KH, Kim SW, et al. Brigatinib in patients with crizotinib-refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2490–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.5904.

Shaw AT, Kim TM, Crinò L, Gridelli C, Kiura K, Liu G, et al. Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND-5): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(7):874–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30339-X.

Novello S, Mazières J, Oh IJ, de Castro J, Migliorino MR, Helland Å, et al. Alectinib versus chemotherapy in crizotinib-pretreated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from the phase III ALUR study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(6):1409–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy121.

Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):829–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1704795.

Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, Wu YL, Paz-Ares L, Wolf J, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):917–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30123-X.

Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JCH, Han JY, Hochmair MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in advanced ALK inhibitor-naive ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer: second interim analysis of the phase III ALTA-1L trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(31):3592–603. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00505.

Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Katayama R, et al. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to first- and second-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-rearranged lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(10):1118–33. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0596.

Johnson TW, Richardson PF, Bailey S, Brooun A, Burke BJ, Collins MR, et al. Discovery of (10R)-7-amino-12-fluoro-2,10,16-trimethyl-15-oxo-10,15,16,17-tetrahydro-2H-8,4-(metheno)pyrazolo[4,3 -h][2,5,11]-benzoxadiazacyclotetradecine-3-carbonitrile (PF-06463922), a macrocyclic inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and c-ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) with preclinical brain exposure and broad-spectrum potency against ALK-resistant mutations. J Med Chem. 2014;57(11):4720–44. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm500261q.

Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Felip E, Soo RA, Camidge DR, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1654–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30649-1.

Shaw AT, Bauer TM, de Marinis F, Felip E, Goto Y, Liu G, et al. First-line lorlatinib or crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2018–29. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2027187.

Gadgeel S, Peters S, Mok T, Shaw AT, Kim DW, Ou SI, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in treatment-naive anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) non-small-cell lung cancer: CNS efficacy results from the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(11):2214–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy405.

Mok T, Camidge DR, Gadgeel SM, Rosell R, Dziadziuszko R, Kim DW, et al. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(8):1056–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.478.

Barata F, Aguiar C, Marques TR, Marques JB, Hespanhol V. Monitoring and managing lorlatinib adverse events in the Portuguese clinical setting: a position paper. Drug Saf. 2021;44(8):825–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-021-01083-x.

INFARMED. Crizotinib: Relatório de avaliação prévia do medicamento para uso humano em meio hospitalar, https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/1424140/Publicação+de+Parecer+net+-+Xalkori+-+1ª+linha+2018/26592f0f-0461-4eb0-8cf6-8fe2e6fdb209. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Xalkori: EPAR—product information, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xalkori-epar-product-information_en.pdf; 2012. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

INFARMED. Ceritinib: Relatório de avaliação prévia do medicamento para uso humano em meio hospitalar, https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/1424140/Publicação+de+Parecer+net+Zykadia+2017/b41c2dd2-f7ae-4269-8e03-c5b97d1b915c. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Zykadia: EPAR - product information, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zykadia-epar-product-information_en.pdf; 2015. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

INFARMED. Alectinib: Relatório público de avaliação prévia do medicamento em meio hospitalar, https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/1424140/Relatório+público+de+avaliação+de+Alecensa+%28alectinib%29+2019/c52f849b-a091-4a3d-9bff-916a79b8acd9. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Alecensa: EPAR - product information, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/alecensa-epar-product-information_en.pdf; 2017. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

INFARMED. https://www.infarmed.pt/web/infarmed/relatorios-de-avaliacao-de-financiamento-publico; Search: brigatinib. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Alunbrig: EPAR - product information, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/alunbrig-epar-product-information_en.pdf; 2018. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

INFARMED. https://www.infarmed.pt/web/infarmed/relatorios-de-avaliacao-de-financiamento-publico; Search: lorlatinib. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

European Medicines Agency. Lorviqua: EPAR - product information, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lorviqua-epar-product-information_en.pdf; 2019. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(7):823–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e318290868f.

Kerr KM, Bubendorf L, Edelman MJ, Marchetti A, Mok T, Novello S, et al. Second ESMO consensus conference on lung cancer: pathology and molecular biomarkers for non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(9):1681–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu145.

Kalemkerian GP, Narula N, Kennedy EB, Biermann WA, Donington J, Leighl NB, et al. Molecular testing guideline for the selection of patients with lung cancer for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the College of American Pathologists/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/Association for Molecular Pathology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(9):911–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.7293.

Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Aisner DL, Arcila ME, Beasley MB, Bernicker et al. Updated molecular testing guideline for the selection of lung cancer patients for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(3):321–346. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2017-0388-CP.

Hendriks LE, Kerr KM, Menis J, Mok TS, Nestle U, Passaro A, Peters S, Planchard D, Smit EF, Solomon BJ, Veronesi G, Reck M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(4):339-357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.12.009.

Kerr KM, López-Ríos F. Precision medicine in NSCLC and pathology: how does ALK fit in the pathway? Ann Oncol. 2016;27 Suppl 3:iii16–iii24. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw302.

Letovanec I, Finn S, Zygoura P, Smyth P, Soltermann A, Bubendorf L, et al. Evaluation of NGS and RT-PCR methods for ALK rearrangement in European NSCLC patients: results from the european thoracic oncology platform lungscape project. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(3):413–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.117.

Illei PB, Wong W, Wu N, Chu L, Gupta R, Schulze K, et al. ALK testing trends and patterns among community practices in the United States. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.18.00159.

Batra U, Nathany S, Sharma M, Pasricha S, Bansal A, Jain P, et al. IHC versus FISH versus NGS to detect ALK gene rearrangement in NSCLC: all questions answered? J Clin Pathol. 2022;75(6):405–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2021-207408.

Waterhouse DM, Tseng WY, Espirito JL, Robert NJ. Understanding contemporary molecular biomarker testing rates and trends for metastatic NSCLC among community oncologists. Clin Lung Cancer. 2021;22(6):e901–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2021.05.006.

Bernicker EH, Xiao Y, Croix DA, Yang B, Abraham A, Redpath S, et al. Understanding factors associated with anaplastic lymphoma kinase testing delays in patients with non-small cell lung cancer in a large real-world oncology database. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2022;146(8):975–83. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2021-0029-OA.

Lin HM, Wu Y, Yin Y, Niu H, Curran EA, Lovly CM, et al. Real-world ALK testing trends in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the United States. Clin Lung Cancer. 2023;24(1):e39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2022.09.010.

Lin C, Shi X, Yang S, Zhao J, He Q, Jin Y, et al. Comparison of ALK detection by FISH, IHC and NGS to predict benefit from crizotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2019;131:62–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.03.018.

Zeng L, Li Y, Xu Q, Jiang W, Lizaso A, Mao X, et al. Comparison of next-generation sequencing and ventana immunohistochemistry in detecting ALK rearrangements and predicting the efficacy of first-line crizotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:7101–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S265974.

Rolfo C, Mack PC, Scagliotti GV, Baas P, Barlesi F, Bivona TG, et al. Liquid biopsy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a statement paper from the IASLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(9):1248–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.030.

Dagogo-Jack I, Brannon AR, Ferris LA, Campbell CD, Lin JJ, Schultz KR, et al. Tracking the evolution of resistance to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors through longitudinal analysis of circulating tumor DNA. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:PO.17.00160. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00160.

McCoach CE, Blakely CM, Banks KC, Levy B, Chue BM, Raymond VM, et al. Clinical utility of cell-free DNA for the detection of ALK fusions and genomic mechanisms of ALK inhibitor resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(12):2758–70. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2588.

Dagogo-Jack I, Rooney M, Lin JJ, Nagy RJ, Yeap BY, Hubbeling H, et al. Treatment with next-generation ALK inhibitors fuels plasma ALK mutation diversity. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(22):6662–70. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1436.

Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Lin CC, Soo RA, et al. ALK resistance mutations and efficacy of lorlatinib in advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(16):1370–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.02236.

Mezquita L, Swalduz A, Jovelet C, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Howarth K, Planchard D, et al. Clinical relevance of an amplicon-based liquid biopsy for detecting ALK and ROS1 fusion and resistance mutations in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4:PO.19.00281. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.19.00281.

Spicer J, Tischer B, Peters M. EGFR mutation testing and oncologist treatment choice in advanced Nsclc: global trends and differences. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 1):i57–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv128.04.

Barata F, Fidalgo P, Figueiredo S, Tonin FS, Duarte-Ramos F. Limitations and perceived delays for diagnosis and staging of lung cancer in Portugal: a nationwide survey analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252529. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252529.

Lim C, Tsao MS, Le LW, Shepherd FA, Feld R, Burkes RL, et al. Biomarker testing and time to treatment decision in patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(7):1415–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv208.

Cheema PK, Menjak IB, Winterton-Perks Z, Raphael S, Cheng SY, Verma S, et al. Impact of reflex EGFR/ALK testing on time to treatment of patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(2):e130–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2016.014019.

Pisano C, De Filippis M, Jacobs F, Novello S, Reale ML. Management of oligoprogression in patients with metastatic NSCLC harboring ALK rearrangements. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(3):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030718.

Duruisseaux M, Besse B, Cadranel J, Pérol M, Mennecier B, Bigay-Game L, et al. Overall survival with crizotinib and next-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (IFCT-1302 CLINALK): a French nationwide cohort retrospective study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):21903–17. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15746.

Ceddia S, Codacci-Pisanelli G. Treatment of brain metastases in ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;165:103400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103400.

Ito K, Yamanaka T, Hayashi H, Hattori Y, Nishino K, Kobayashi H, et al. Sequential therapy of crizotinib followed by alectinib for non-small cell lung cancer harbouring anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement (WJOG9516L): a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2021;145:183–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.12.026.

Le Rhun E, Guckenberger M, Smits M, Dummer R, Bachelot T, Sahm F, et al. EANO-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with brain metastasis from solid tumours. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(11):1332–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.016.

Shaw AT, Friboulet L, Leshchiner I, Gainor JF, Bergqvist S, Brooun A, et al. Resensitization to crizotinib by the lorlatinib ALK resistance mutation L1198F. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1508887.

Sudman S, Bradburn N. Effects of time and memory factors on response in surveys. J Am Stat Assoc. 1973;68(344):805–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2284504.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the colleagues who responded to the questionnaire, representing their centres, thus making it possible to assess the way in which ALK-positive patients are treated in mainland Portugal and in Madeira and the Azores. Medical writing assistance was provided by Sofia Arriaga Cerqueira, PhD, on behalf of Springer Healthcare Ibérica and was funded by Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was funded by Pfizer and the development of this manuscript was proposed to all authors by the funding source. Pfizer had no role in data collection or in the decision of the content of the article. The open access fee was sponsored by Pfizer.

Conflicts of interest

AF declares that she has received honoraria from BMS, Boehringer, MSD, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Roche, and Takeda. AR declares that she has received honoraria from BMS, MSD, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. CG declares that she has received honoraria from MSD, BMS, Takeda, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Jansen. MF declares that she has received honoraria from MSD, AstraZeneca, Merck, Takeda, and Pfizer. All authors were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval

This study was based on a questionnaire related to physicians’ clinical practice and, although it involved human participants, it did not include any intervention. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not deemed necessary. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: preparation of the questionnaire, data collection and analysis, and paper conception were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was critically revised by all authors. All authors confirm that they have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Figueiredo, A., Rodrigues, A., Gaspar, C. et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Advanced ALK Rearrangement-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in Portugal: Results of a National Questionnaire. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 545–555 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00393-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00393-z